Introduction

Family trees make a valuable contribution to understanding the relevance of the patient’s family history in comprehensive primary healthcare provision. Throughout history, family trees have offered an extraordinary source of information to improve the understanding and treatment of common chronic illnesses, including coronary heart disease, diabetes, various cancers, osteoporosis, and asthma (Keen et al., Reference Keen, Hart, Arden, Doyle and Spector1999; Burke et al., Reference Burke, Fesinmayer, Reed, Hampson and Carlsten2003; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Hindorff, Kim, Wines, Bowen, McGrath and Edwards2003; Kardia et al., Reference Kardia, Modell and Peyser2003; Ziogas and Anton-Culver, Reference Ziogas and Anton-Culver2003; McGoldrick et al., Reference McGoldrick, Gerson and Petry2020). There is growing recognition that family trees also support tailored disease prevention, which may be more effective than existing approaches (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Baird, Botkin, Driscoll, Fishman, Guarino, Hiatt, Jarvik, Millon-Underwood, Morgan, Mulvihill, Pollin, Schimmel, Stefanek, Vollmer and Williams2009). Family trees are often defined in medical literature as ‘family history’. The concept is grounded on the repeatedly verified hypothesis that similar diseases are based on common genetics. Taking a detailed family history represents the cornerstone of the genetic risk assessment, as it helps to ensure that important genetic information is not overlooked (Vance, Reference Vance2020; Bylstra et al., Reference Bylstra, Lim, Kam, Tham, Wu, Teo, Davila, Kuan, Chan, Bertin, Yang, Rozen, Teh, Yeo, Cook, Jamuar, Ginsburg, Orlando and Tan2021). There is a wide variety of diseases that can be found in the medical literature. There are diseases that are inherited directly from parents and diseases that medical professionals believe are not transmitted from one generation to another. The medical literature discussing how similar diseases are based on common genetics argues that Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, congenital hearing loss, iron overload, venous thromboembolism, chronic respiratory disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disease, antisocial personality disorder, depression, birth defects, and various malignancies have genetic components (Rich et al., Reference Rich, Burke, Heaton, Haga, Pinsky, Short and Acheson2004; Dolan and Moore, Reference Dolan and Moore2007; Holt and Sly, Reference Holt and Sly2009; De Hoog et al., Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014; Dhiman et al., Reference Dhiman, Kai, Horsfall, Walters and Qureshi2014; Vaughn et al., Reference Vaughn, Salas-Wright, DeLisi and Qian2015; Al-Mamun et al., Reference Al-Mamun, Sarker, Qadri, Shirin, Mohammad, LaRocque, Karlsson, Saha, Asaduzzaman, Qadri and Mannoor2016).

Family trees also have a social component. FPs have always asked patients about their family history to gain insight into their social and medical backgrounds. It helps them understand the context of the patient’s symptoms in terms of environmental and lifestyle causes of disease and the patient’s concerns about the nature of the illness (Emery and Rose, Reference Emery and Rose1999; Dolan and Moore, Reference Dolan and Moore2007). Within the medical profession, especially in family medicine, there is a general consensus that medical care will be transformed profoundly as advances in understanding family trees (genetic, family, and social components) become incorporated into diagnosis, treatment, and prevention (Emery and Rose, Reference Emery and Rose1999; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Scheuner, Peterson-Oehlke, Gwinn, Faucett and Khoury2002; Guttmacher et al., Reference Guttmacher, Collins and Carmona2004; Qureshi et al., Reference Qureshi, Bethea, Modell, Brennan, Papageorgiou, Raeburn, Hapgood and Modell2005; Emery et al., Reference Emery, Morris, Goodchild, Fanshawe, Prevost, Bobrow and Kinmonth2007; Qureshi et al., Reference Qureshi, Carroll, Wilson, Santaguida, Allanson, Brouwers and Raina2009; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Scheuner, Jorgensen and Khoury2009; Flynn et al., Reference Flynn, Wood, Ashikaga, Stockdale, Dana and Naud2010; Mathers et al., Reference Mathers, Greenfield, Metcalfe, Cole, Flanagan and Wilson2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Collingridge and Williams2011; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Carroll, Allanson, Little, Etchegary, Avard, Potter, Castle, Grimshaw and Chakraborty2012; Baer et al., Reference Baer, Schneider, Colditz, Dart, Andry, Williams, Orav, Haas, Getty, Whittemore and Bates2013; De Hoog et al., Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014; Emery et al., Reference Emery, Reid, Prevost, Ravine and Walter2014; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Hayward and Ahmed2016; Al-Mamun et al., Reference Al-Mamun, Sarker, Qadri, Shirin, Mohammad, LaRocque, Karlsson, Saha, Asaduzzaman, Qadri and Mannoor2016; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Johnson, Clamp and Wyatt2016).

Family trees are traditionally regarded as a routine part of obtaining the medical history, but it is not used in a systematic way in clinical practice (Langlands et al., Reference Langlands, Prentice and Ravine2010; Emery et al., Reference Emery, Walter and Ravine2010). This article reviews various approaches in the design and use of family trees in family medicine. It examines how this field of family medicine is regulated internationally and what Slovenia could learn from practices elsewhere. In addition, it examines problems with and/or barriers to the design and application of family trees, which have been pointed out by FPs. Therefore, it uses secondary analysis to obtain information from the systematic review performed (Gülpinar and Güçal Güçlü, Reference Gülpınar and Güçal Güçlü2013). The aim of this study is a systematic literature review of the purpose, design, and use of family trees in family medicine settings.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted strictly in line with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) recommendations (Bolha et al., Reference Bolha, Blaznik and Korošec2021; Ho Man et al., Reference Ho Man, Khoo, Velaga, Yeong, Yeo Teo, Goh, Su-Chong Low, Yip Chan, Kiat Hon and Lee2019).

Literature search

Search strategies were developed and undertaken for the time period April 1999 to October 2019. Consistent with similar review studies (Bolha et al., Reference Bolha, Blaznik and Korošec2021; Ho Man et al., Reference Ho Man, Khoo, Velaga, Yeong, Yeo Teo, Goh, Su-Chong Low, Yip Chan, Kiat Hon and Lee2019), a search engine was utilized to find scholarly literature related to family tree/history research. The Web of Science (WoS), an interdisciplinary electronic resource, was used as the relevant database. The English expressions family, tree, and family history were used as search terms. To find potential publications in Slovenian, the Cobiss system was used to search for results under Slovenian keywords.

Grading criteria were used to select the relevant articles. In the first step, the search results were reduced by filtering for articles posted in the last ten years and articles in English. The selected articles were then systematically reviewed. Original research that dealt with family trees was used as the inclusion criterion. Exclusion criteria included clinical case presentations, research protocols, columns, and opinions or comments. In the systematic review described, 24 articles were selected that met all the criteria (Table 1).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

* Review studies are of utmost importance because family trees are analysed from the perspective of many research fields. Exporting them would risk overlooking some very important and high-quality studies.

The QUOROM statement and qualitative analysis

After elimination by field of study, the selected publications were additionally systematically reviewed. The verified QUOROM statement for ‘improving the quality of reporting of meta-analysis’ was applied (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Cook, Eastwood, Olkin, Rennie and Stroup1999) in the field selected. We used a verified checklist for standards for reporting meta-analysis. It is a holistic framework that includes an abstract, an introduction, methods, results, and a discussion/conclusion.

Because the field of research covers not only medical studies, only the original checklist (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Cook, Eastwood, Olkin, Rennie and Stroup1999) was slightly adapted. The checklist is organized into separate categories focused on the search, selection validity assessment, study characteristics, quantitative/qualitative data synthesis, and trial flow. It is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Quality assessment checklist

Source: adapted from Moher et al. (Reference Moher, Cook, Eastwood, Olkin, Rennie and Stroup1999, p. 1897).

The literature examining family trees and the significance of their use in family medicine was analysed in greater detail. In doing so, focus was placed on important segments (various categories) of family tree research that are primarily useful in family medicine. This yielded a comprehensive distribution of studies by group, according to the topic or the manner in which family trees are used in the studies.

Results

Basic information

The most general result obtained in the WoS database with the search string (((ALL = (family)) AND ALL = (history)) AND ALL = (tree))) was 4,558 publications. Because these were studies from 197 different fields, areas relevant to research on family trees/history in medicine were selected in the next step.

In the areas directly related to medicine, 369 publications were identified across 32 groups or fields. When selecting the fields, the criterion observed was that the field had to contain the word medicine and that it had to belong to a medical science.

The publication search and selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. After excluding publications from irrelevant fields, the authors focused on only 32 subfields of medicine. The screening process revealed 369 studies as relevant. After the review of titles and abstracts, 277 publications were excluded. In that way, 79 full studies were obtained, of which 55 were finally excluded due to unsatisfactory material and/or a lack of relevant data about the usefulness of family trees/history in family (primary care) medicine.

Figure 1. A PRISMA flow diagram of the literature review strategy applied.

Ultimately, the systematic review identified 24 studies. These studies can be roughly divided into three groups. The first group deals with technological challenges in family tree design, the second group focuses on the possibility of setting up national databases, and the third group examines family physicians and their views on the feasibility of using family trees at the primary healthcare level.

Main features of studies included in the systemic review

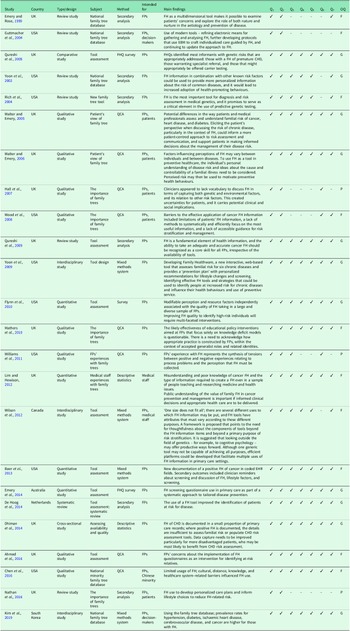

The main features of each registered study are reviewed in Table 3.

Table 3. Main features and quality assessment of studies included in the systematic review

Note: The studies are arranged in chronological order; FH = family history; EBM = evidence-based medicine; FHQ = family history questionnaire; CHD = coronary heart disease; QCA = qualitative content analysis; Q1 = Is the research question or study aim clearly stated?; Q2 = Is the study properly defined and conceptually clearly defined?; Q3 = Is the population in the study fully described? Is the sampling proper?; Q4 = Are the statistical methods described well?; Q5 = Are the results presented in a transparent and clear manner?; Q6 = Are the advantages and disadvantages of the research clear?; Q7 = Is the discussion rich in content and are the findings/conclusions clear?; OQ = Overall quality rating (P = Poor, F = Fair, G = Good).

The trend is encouraging and in line with the assumptions or the goal of this research. The studies included in the review (Table 3) were published between 1999 and 2019. Altogether, 24 studies have reported on attempts to establish national family tree databases, and they drew attention to the importance of family trees at the primary healthcare level. The studies also emphasized the importance of evaluating tools for making family trees by FPs, and they revealed the FPs’ views on the importance of using family trees at primary care clinics.

The studies analysed have different methodological approaches. In addition to traditional positivist and comparative studies, there are also qualitative studies. In the latter, researchers deal with issues related to family trees inductively, from the bottom up, and in this way try to create paradigmatic models to justify the use of family trees in medicine and other fields. Such an approach is probably also the greatest added value in research on an under-researched area.

In the second part, a composite coder assessed the quality of the studies analysed. Although each study is an important part of the research puzzle, the quality of the research varies. The results of the analysis based on the previously designed checklist are presented in Table 3.

The results of the qualitative assessment of the studies included in the analysis showed that the majority of the studies were conducted correctly. Moreover, most of the studies could be rated as good because they meet all the research criteria, which is also confirmed by the journals the studies are published in. In addition to being set up correctly, these studies are also methodologically grounded, the populations are clearly defined, the sampling is correct, and the results are transparent.

Certain studies (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Saukk, Evans, Qureshi and Humphries2007; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Collingridge and Williams2011; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Johnson, Clamp and Wyatt2016) have clearly defined objectives but lack a well-defined methodological approach. Moreover, the same studies are flawed by conclusions that are not described as clearly as possible. Some studies, although we rated them as good, do not have the advantages and disadvantages (limitations) listed. However, we considered this to be a less important feature.

The assessment of the quality of the selected studies follows the methodology set out in the introduction on a systematic review of the literature. On the other hand, a systematic review of the literature should offer a certain typology that would classify the available studies according to their content and object of research. Only in this way will the potential and quality of the studies analysed, which deal with family trees from different perspectives, become apparent.

With this aim, in the discussion (below), in interaction with the ideas of the best-quality studies included in our analysis, we highlight a typology that includes four categories. The first group of studies focuses on tools and technologies for collecting and managing family trees in medicine; the second focuses on the need to establish national databases; the third focuses on FPs’ views and understanding the potential of family trees; and the fourth raises ethical, legal, and social questions related to the creation of family trees and their use in medical practice.

Discussion

Tools and technology

The creation of family trees involves various tools, such as face-to-face interviews and medical history questionnaires, and obtaining or confirming genealogical information, sometimes with the involvement of genetics experts. FPs are primarily in charge of designing family trees. This process is often time consuming because it requires commitment, meticulousness, and entering data into a database (Emery and Rose, Reference Emery and Rose1999; Rich et al., Reference Rich, Burke, Heaton, Haga, Pinsky, Short and Acheson2004; De Hoog et al., Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014).

Over the past decade, increasingly more studies have emerged in which researchers investigate how to use technology to make it easier for FPs to prepare family trees (Qureshi et al., Reference Qureshi, Bethea, Modell, Brennan, Papageorgiou, Raeburn, Hapgood and Modell2005; Qureshi et al., Reference Qureshi, Carroll, Wilson, Santaguida, Allanson, Brouwers and Raina2009; Scheuner et al., Reference Scheuner, de Vries, Kim, Meili, Olmstead and Teleki2009; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Carroll, Allanson, Little, Etchegary, Avard, Potter, Castle, Grimshaw and Chakraborty2012; Baer et al., Reference Baer, Schneider, Colditz, Dart, Andry, Williams, Orav, Haas, Getty, Whittemore and Bates2013; De Hoog et al., Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014). De Hoog et al. (Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014) identified 18 different family history tools and offered a holistic taxonomy that refers to the types of diseases for which family trees are used, the healthcare levels in which they are used (primary, secondary, etc.), and the degree of computerization/digitization of a particular tool.

Qureshi et al. (Reference Qureshi, Bethea, Modell, Brennan, Papageorgiou, Raeburn, Hapgood and Modell2005) developed a similar taxonomy in their study. They also identified 18 family history tools, with 11 developed for use in primary care. In addition to the fact that some of the tools are based on a CSAQ (computerized self-administered questionnaire) survey approach, virtually no family history tools provide an electronic database that would be compatible with other medical databases. In an era of widespread digitization, this weakness should be eliminated, which has been pointed out by other healthcare researchers (e.g., Menvielle et al., Reference Menvielle, Audrain-Pontevia and Menvielle2017).

Baer et al. (Reference Baer, Schneider, Colditz, Dart, Andry, Williams, Orav, Haas, Getty, Whittemore and Bates2013) offered a web application in which patients enter data themselves. The Your Health Snapshot (YHS) tool is a patient-administered, web-based risk appraisal tool that was constructed using a risk assessment framework. More than a family tree, YHS is a tool that ‘assigns relative risk estimates to environmental, dietary, and lifestyle factors based on relevant epidemiologic studies’. A similar web-based tool was also developed in 2004 by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Scheuner, Jorgensen and Khoury2009).

Family tree tools are frequently used to collect information that is not directly related to the family tree. This was pointed out by Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Carroll, Allanson, Little, Etchegary, Avard, Potter, Castle, Grimshaw and Chakraborty2012), who found that, although one generic tool is not capable of achieving all purposes (especially not at all levels of healthcare), there is a need for efficient platforms that facilitate multiple uses of family history information in primary care medicine. This is widely discussed among researchers dealing with national family tree databases, which is addressed in the next section.

National family tree databases

National family tree databases should become part of routine practice in family medicine. The idea of a national database system of family trees is not new in primary healthcare medicine. Studies in which researchers have pointed to the importance of national databases date back to the 1990s (Kinmonth et al., Reference Kinmonth, Reinhard, Bobrow and Pauker1998; Emery and Rose, Reference Emery and Rose1999). These studies describe several attempts to create a national database of family trees at the primary healthcare level. Similar contributions are also found today (Emery et al., Reference Emery, Reid, Prevost, Ravine and Walter2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hong, Cho and Park2019).

South Korea has a national social health insurance system, which reached universal coverage of all Korean residents in 1989 (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hong, Cho and Park2019). In addition to the demographic, socioeconomic, and disability registration information, this system includes a wide range of health risk factors, it facilitates national health screening programmes (general checkups, cancer screening, etc.), and it provides detailed information on the healthcare utilization of all insured residents. The key result of this system is the National Health Information Database (NHID), which was created to meet various demands for data. Because the NHID has some limitations, Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Hong, Cho and Park2019) developed a special code system to logically convey interpersonal relationships within families and establish a database of interpersonal family relationships of the entire population.

The South Korean attempt and similar ones, of course, were conditional on the development of technology that determines the development of various subfields of family medicine (Jenkins and Oyama, Reference Jenkins and Oyama2020). A common problem that virtually all researchers point out is the incoherence and incompatibility of family trees with other medical databases in the country. De Hoog et al. (Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014) found that no family tree/history tool (out of 18 examined) allows for the electronic transfer of family tree information to electronic medical record systems. Researchers have reported similar findings in the case of Australia (Emery et al., Reference Emery, Reid, Prevost, Ravine and Walter2014).

The existence of a national database depends on the institutional structure of the health and social security system in the country. In countries with underdeveloped health infrastructure (e.g., public institutions, insurance companies, and support infrastructure), it is unrealistic to expect there to be a national family tree database at the primary healthcare level (De Hoog et al., Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014). On the other hand, the creation of a national system requires the goodwill of FPs, who are the primary sources of information about patients and their families. Making family trees requires resources and time that FPs do not usually have (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Collingridge and Williams2011). Sometimes there are also other barriers, which are discussed below.

Slovenia has no national family tree database at the primary healthcare level. Moreover, the present study is the first to highlight the untapped potential of family trees for the development of family medicine in Slovenia. In the past, only some bachelor’s and master’s theses have been written, in which the importance of family trees in the FPs’ treatment of chronic diseases was highlighted (Praprotnik, Reference Praprotnik2014).

Family physicians’ perspective

Most studies examining FPs’ views on the creation and use of family trees are based on a qualitative approach. Researchers conduct individual and group interviews (focus groups), in which FPs are asked a wide variety of questions about family trees and their use in primary medicine (Walter and Emery, Reference Walter and Emery2006; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Stockdale and Flynn2008; Mathers et al., Reference Mathers, Greenfield, Metcalfe, Cole, Flanagan and Wilson2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Collingridge and Williams2011). These studies can be roughly divided into two groups: 1) studies discussing the increasing usability of family trees in primary medicine, and 2) studies in which FPs point out the difficulties in and barriers to creating a (national) family tree database.

Mathers et al. (Reference Mathers, Greenfield, Metcalfe, Cole, Flanagan and Wilson2010) found that family trees (and genetic concepts more generally) are clearly part of current family practice in the UK. It was once the case that FPs solely looked ‘for social and psychological influence via the family history’. This has changed; today’s practice is different. According to Mathers et al. (Reference Mathers, Greenfield, Metcalfe, Cole, Flanagan and Wilson2010), for British FPs a family tree is more than a diagnostic/risk assessment tool. It exists within the wider concept of the family doctor and offers insight into other facets of patients and families. Researchers from other countries and/or specific ethnic groups have also come to the same conclusion (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Saukk, Evans, Qureshi and Humphries2007; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Stockdale and Flynn2008; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Collingridge and Williams2011; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Talwar, Xu and Zhao2016).

In general, the positive experiences of FPs are associated with the versatile usefulness of family trees. On the other hand, regarding difficulties in creating (and using) a family tree database, FPs have highlighted the following issues: the fact that family tree data needs to be collected, which is time consuming; confusion about the use of family trees; perceived inaccuracies and incompleteness of the information provided; and the personal liability of FPs, which contributes to a negative experience (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Collingridge and Williams2011).

However, some systemic features should be highlighted as central barriers to creating a national family tree database. It is often overlooked that FPs do not decide to design family trees. In Slovenia, for example, doctors are part of the public health system, which is mostly financed through the national health insurance system, which does not provide adequate motivation for innovation. This means that FPs are paid to treat patients and not to perform activities that require additional time and work (e.g., creating family trees). The FPs interviewed in other countries expressed the same concerns (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Saukk, Evans, Qureshi and Humphries2007; Mathers et al., Reference Mathers, Greenfield, Metcalfe, Cole, Flanagan and Wilson2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Collingridge and Williams2011).

Family history has garnered increased attention as a means to help clarify a person’s risk of developing common chronic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, asthma, and certain types of cancer. That is why interest in researching and developing family trees is growing. The medical profession agrees on the importance of family trees as a valuable source of data for understanding and treating patients. Virtually all the authors cited suggest that family trees are a tool that all countries should have in the digital age. The literature also acknowledges the importance of national family tree databases that are compatible with other digital medical registries (De Hoog et al., Reference De Hoog, Portegijs and Stoffers2014). However, there are some obstacles and barriers in the field. Data are collected across many models and with many tools, which means databases are often incompatible with one another (Qureshi et al., Reference Qureshi, Bethea, Modell, Brennan, Papageorgiou, Raeburn, Hapgood and Modell2005). The burden of creating family tree databases in most countries is tied to the primary healthcare level. FPs collect and communicate information they receive from patients through interviews or pre-designed questionnaires. Because this work is indeed time consuming and, in most cases, unpaid, the databases are often deficient, or they do not exist at all.

Despite recent insights into the importance of family trees and family tree databases in primary care, there appear to be substantial barriers to developing family trees and creating databases, including overburdened doctors, inadequate payment systems and reimbursement policies for FPs, current modes of organizing family medicine practices, varying patient expectations, inaccurate information reported by patients, a lack of proper training to collect and interpret family trees, and a lack of FPs’ own knowledge and skills. FPs may neglect family history because of the amount of time required to collect the information. They were likely to report ‘lack of time during the visit’ as a barrier. Certainly, FPs typically spend far less time obtaining family tree information than suggested by family medicine experts. Overcoming the problem of the time and effort required for creating and analysing family trees remains a daunting challenge (Rich et al., Reference Rich, Burke, Heaton, Haga, Pinsky, Short and Acheson2004).

Ethical, legal, and social issues

Furthermore, family trees raise issues of ethical and legal implications, including privacy, confidentiality, data ownership, and informed consent. FPs should be aware of the ethical, legal, and social implications of collecting family tree information, particularly in the current climate of uncertainty about the privacy of medical information. Various legal issues can affect the collection of family history information under some circumstances, including informed consent, data ownership and protection, obligation to disclose data, and reporting requirements. In addition, the potential negative outcomes of assessing family history must be considered carefully. For example, limited information has been obtained about stigmatization, discrimination, privacy/confidentiality, and personal, family, and social issues associated with family history assessment and risk labelling (Lucassen et al., Reference Lucassen, Parker and Wheeler2006). Labelling a person as high or moderate risk for disease may have important psychological, social, and economic costs. The use of a family history tool for public health purposes could only be successful if people perceived greater benefit than risk associated with revealing family medical information, if there was no stigma associated with being at above-average risk, and if there were interventions and options for behaviour change that could make a difference in reducing morbidity and mortality (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Scheuner, Peterson-Oehlke, Gwinn, Faucett and Khoury2002).Although most FPs are aware of the potential for fatalism, anxiety, impairment of self-image, depression, or blame associated with collecting family history information, no data are available to suggest that these unintended behaviours or feelings do in fact occur or, if they do, how common they are. This is another aspect of obtaining family trees that requires further research (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Scheuner, Jorgensen and Khoury2009).

Both researchers and FPs agree that the issue of family tree databases needs to be regulated at the systemic level. Certain countries can provide best practice examples (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hong, Cho and Park2019). In fact, the creation of national family tree databases requires a holistic and sustainable approach (Nardi et al., Reference Nardi, Berti, Fabbri, Di Pasquale, Iori, Mathieu, Vescovo, Fontanella, Mazzone, Campanini, Nozzoli and Manfellotto2013) that will justify the initial costs of creation and clearly highlight the benefits that doctors, patients, and their relatives can derive from this. Only then can the second step take place, the selection of a model that may be eclectic but validated at the national level. Therefore, joint action by decision-makers, the healthcare system, responsible institutions, doctors, and patients (a group not addressed in this study; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Saukk, Evans, Qureshi and Humphries2007) is required.

Conclusion

Family trees should make their way into family practice as a routine procedure with their own qualities. Family trees are a tool that can significantly contribute to better patient care. A review of experiences from other countries has revealed some challenges. Designing family trees is a demanding task that should not be delegated only to FPs. Therefore, there is a need to create a national family tree database through the collaboration of FPs and relevant health institutions. The creation of a national database would require the involvement of all stakeholders, including FPs, politicians, and technical staff to set up the system operationally. The versatility of using a national family tree database is confirmed by virtually all studies that were analysed in detail. A national database would be an extremely useful tool for the development of family medicine.

Funding statement

The study was funded by Dr. Adolf Drolc Maribor Health Centre, Ulica talcev 9, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Ethical standards

The method used in this systematic literature review involves no ethical issues. No ethical approval was therefore needed.