Introduction

In primary care, the most common acute presentation in women is uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Francis, Thomas-Jones, Llor, Bongard, Moore, Little, Bates, Lau, Pickles, Gal, Wootton, Kirby, Gillespie, Rumbsy, Brugman, Hood and Verheij2017). Every second woman experiences an uncomplicated UTI at least once in her lifetime (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Francis, Thomas-Jones, Llor, Bongard, Moore, Little, Bates, Lau, Pickles, Gal, Wootton, Kirby, Gillespie, Rumbsy, Brugman, Hood and Verheij2017). In 2016, in the Netherlands, the prevalence of uncomplicated UTI in women was 103.5 per 1000 patient-years. The Dutch guideline for General Practitioners (GPs) for UTI treatment (2013) recommended the following antibiotics for treatment of uncomplicated UTI: nitrofurantoin as the first choice, fosfomycin as the second choice and trimethoprim as the third choice (Van Pinxteren et al., Reference Van Pinxteren, Knottnerus, Geerlings, Visser, Klinkhamer, Van Der Weele, Verduijn, Opstelten, Burgers and Van Asselt2013). In this guideline, fosfomycin and trimethoprim changed ranks compared to the preceding 2005 GP guideline. This change was supported by the high in vitro susceptibility of UTI pathogens to fosfomycin, the lack of cross-resistance between fosfomycin and other antibiotics (Knottnerus et al., Reference Knottnerus, Bindels, Geerlings, Moll Van Charante and Ter Riet2008) and the relatively high prevalence of bacterial resistance to trimethoprim (Korstanje et al., Reference Korstanje, Mouton, Bij, Neeling, Mevius and Koene2012). If the response to the first guideline antibiotic for uncomplicated UTI is insufficient, the guideline recommends to start treatment with the second guideline antibiotic for uncomplicated UTI. A recent study in 15 European countries showed that as many as 12 unique antibiotics were listed as the first-line empirical treatment options for uncomplicated UTI (Malmros et al., Reference Malmros, Huttner, Mcnulty, Rodriguez-Bano, Pulcini, Tangden, Thalhammer, Delvaux, Heytens, Bjerrum, Wuorela, Caron, Wagenlehner, Prins, Haug, Kozlov, Barac, Beovic, De Cueto and Grp2019). Nitrofurantoin was the most frequently recommended antibiotic for female patients with this indication and was listed as the first-line option for uncomplicated UTI in 12 out of 15 guidelines, followed by fosfomycin and pivmecillinam.

If an episode of uncomplicated UTI develops into a febrile UTI, the 2013 Dutch guideline advised ciprofloxacin as the first choice, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid as the second choice and co-trimoxazole as the third choice. Compared to the preceding guideline, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and ciprofloxacin changed ranks because of lower bacterial resistance to ciprofloxacin when compared to both amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and co-trimoxazole (Korstanje et al., Reference Korstanje, Mouton, Bij, Neeling, Mevius and Koene2012).

After revisions, new guideline recommendations must be implemented into clinical daily practice, which may take some time, as exemplified by a study in the United States (US) (Durkin et al., Reference Durkin, Keller, Butler, Kwon, Dubberke, Miller, Polgreen and Olsen2018). There, nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole were the first-line antibiotics for uncomplicated UTI treatment according to a 2010 guideline (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Hooton, Naber, Wullt, Colgan, Miller, Moran, Nicolle, Raz, Schaeffer and Soper2011). For 2013, the US study showed that fosfomycin was prescribed for uncomplicated UTI in <0.01% of all visits and almost half of the antibiotic prescriptions were for non-guideline-recommended antibiotics (Durkin et al., Reference Durkin, Keller, Butler, Kwon, Dubberke, Miller, Polgreen and Olsen2018). Qualitative research showed unfamiliarity with fosfomycin as a possible first-line treatment option, along with the belief that fluoroquinolones achieve more rapid and effective control as the most important causes for GPs to ignore guideline recommendations (Grigoryan et al., Reference Grigoryan, Nash, Zoorob, Germanos, Horsfield, Khan, Martin and Trautner2019). Accordingly, in the UK, Clinical Commissioning Groups failed to implement into GP practice the change of nitrofurantoin from second to first choice and trimethoprim from first to second choice in uncomplicated UTI treatment (Croker et al., Reference Croker, Walker and Goldacre2019).

This study aims to describe whether changes in drug preferences in the 2013 revision of the Dutch guideline of UTI for GPs, resulted in corresponding changes in drug choices, based on dispensing data for adult women in the Netherlands (2012–2017).

Methods

Design

An observational cross-sectional study was performed per calendar year (2012–2017) with routinely collected dispensing data from community pharmacies in the Netherlands.

Setting

In the Netherlands, antibiotics are only available through prescription. UTI is mainly treated in primary care. Overall, GPs in the Netherlands prescribe electronically, and their information systems offer electronic prescribing advice according to current GP guideline recommendations (NHG, 2018). Prescriptions from GPs are sent electronically to community pharmacists. Most patients in the Netherlands visit one community pharmacy; consequently, pharmacists have complete virtual dispensing information for individual patients at their disposal (Buurma et al., Reference Buurma, Bouvy, De Smet, Floor-Schreudering, Leufkens and Egberts2008).

Data source

Dispensing data were available from the Dutch Foundation of Pharmaceutical Statistics (SFK) (SFK, 2017). SFK routinely collects dispensing data from over 90% of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands. The total number of community pharmacies in the Netherlands was 1981 in 2012 and 1989 in 2017. SFK data cover GP prescriptions and outpatient prescriptions from medical specialists. The data provided detailed information on the type and number of dispensings, the total amount of Defined Daily Dose (DDD) dispensed per year (WHOCC, 2020) and information about the prescriber (GP or medical specialist). Drugs were coded by the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification system (ATC) (WHOCC, 2020). Information on patients’ sex and year of birth were also available. The data did not contain information on clinical diagnoses. SFK data were coded and not retraceable by the researchers to individual patients or pharmacies. During the research period for each calendar year, data were used from those community pharmacies that had provided complete data throughout the year.

Analysis

In each calendar year from 2012 to 2017, all women, 18 years and older, with at least one dispensing of the uncomplicated UTI guideline drugs nitrofurantoin (ATC code: J01XE01), fosfomycin (J01XX01), or trimethoprim (J01EA01), were counted. For these women, information was retrieved about their age, the prescriber of the antibiotic (GP or other prescribers), presence of the first dispensing in the corresponding year (defined as no dispensing of the same drug during the preceding 12 months), and at least one dispensing of an antibiotic for febrile UTI prescribed within 14 days after a dispensing of a guideline antibiotic for uncomplicated UTI. Numbers of women were counted annually for antibiotic use in uncomplicated or complicated UTIs. To enable comparison between calendar years, for each year, patient numbers from the included pharmacies were extrapolated to the total number of Dutch community pharmacies in that calendar year. Proportions were calculated for the users of individual antibiotics within all users of one of the UTI guideline antibiotics. User numbers were stratified for women with the first dispensing of one of the uncomplicated UTI guideline drugs, the GP as initiating prescriber, and women with a subsequent treatment course for febrile UTI. To provide more detailed insight into treatment choices for age categories, sub-analyses were performed for 2017 (the most recent year). Proportions were calculated as descriptive statistics. Data were analysed with SPSS software, version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In 2012, data were available from 1608 community pharmacies (81% of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands) up to 1765 community pharmacies in 2017 (89% of all pharmacies). Our evaluation for 2012 showed that 743,692 women, 18 years and older, received at least 1 of the 3 antibiotics recommended in the 2013 GP guideline for uncomplicated UTI treatment (Table 1). This number continuously increased to 787,214 women in 2017.

Table 1. Guideline-preferred drugs for treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women ≥18 years between 2012 and 2017

a The number of users was extrapolated to number of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands within the corresponding calendar year. In 2012, data were available from 1608 community pharmacies (81% of all community pharmacies), in 2013 from 1681 (85% of all community pharmacies), in 2014 from 1732 (88% of all community pharmacies) in 2015 from 1774 (90% of all community pharmacies), in 2016 from 1806 (91% of all community pharmacies) and in 2017 from 1765 community pharmacies (89% of all community pharmacies).

b The sum of users of all guideline drugs per year is higher than 100% due to patients with more than one type of guideline drug per year.

Figure 1 shows that the percentage of women with a dispensing for nitrofurantoin within all users of uncomplicated UTI antibiotics was relatively stable with 87.4% (n = 650,337) in 2012 and 84.4% (n = 664,732) in 2017. The percentage of women with a dispensing for fosfomycin increased from 5.4% (n = 40,187) in 2012 to 21.8% (n = 171,327) in 2017. Simultaneously, the percentage of women receiving trimethoprim decreased from 17.8% (n = 132,269) in 2012 to 8.9% (n = 69,766) in 2017.

Figure 1. Percentages# of users of the first, second and third choice guideline antibiotics for acute cystitisa in women ≥18 years between 2012 and 2017#.

#The proportions were calculated after extrapolation of the number of users to the number of users of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands within the corresponding calendar year; in 2012, data were available from 1608 community pharmacies (81% of all community pharmacies), in 2013 data from 1681 pharmacies(85% of all community pharmacies), in 2014 data from 1732 pharmacies (88% of all community pharmacies) in 2015 data from 1774 pharmacies (90% of all community pharmacies), in 2016 data from 1806 pharmacies (91% of all community pharmacies) and in 2017 data from 1765 pharmacies (89% of all community pharmacies).

aNitrofurantoin, fosfomycin or trimethoprim.

The number of women with dispensings of fosfomycin steadily increased annually from 40,187 in 2012 to 101,151 in 2017. In 2013, the user number increased to 64,831, twice the increase from 2011 to 2012. In 2014, the user number increased to 101,151 and in 2015, the user number increased to 124.457.

Percentages of starters with any of the three guideline antibiotics were between 85.4 % in 2012 and 88.0% in 2017. Within starters, percentages for those with a GP prescription were quite stable between 90.4% in 2015 and 91.8% in 2013. Most frequently, nitrofurantoin was chosen in initial UTI treatment. Percentages of starters with this drug within all starters of UTI drugs slightly decreased from 78.4% in 2012 to 73.1%. in 2017. Within age groups, percentages of starters with nitrofurantoin within starters of all UTI guideline drugs were highest for women between 18 and 30 years (89.2%) and lowest in the age category 81 years or older (66.4%, Table 2). Percentages of starters with fosfomycin within all starters increased from 5.2% in 2012 up to 19.2% in 2017. Percentages of starters with fosfomycin were lowest with 12.7% in the age category 18–30 years and highest with 36.2% in the category 81 years and older.

Table 2. Choice of guideline drugs for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in 2017 stratified for age category

a The number of users was extrapolated to the number of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands in 2017; in 2017, data were available from 1765 community pharmacies (89% of all community pharmacies).

b The sum of users of all guideline drugs per year is higher than 100% due to patients with more than one type of guideline drug per year.

c No dispensing of the same drug within the preceding 12 months.

Percentages of women with a dispensing for an antibiotic to treat febrile UTI within 14 days after an uncomplicated UTI antibiotic remained stable, remaining at 5.6% throughout the study period (Figure 2). Use of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid declined during the study period (2.9% in 2012 to 1.8% in 2017), whereas the use of ciprofloxacin increased from 1.9% in 2012 to 3.3% in 2017. The use of co-trimoxazole was relatively stable, with 0.7% in 2012 and 0.5% in 2017.

Figure 2. Percentages# of users of guideline antibiotics for febrile UTIb within 14 days after the first, second or third choice guideline antibiotics for acute cystitisa in women ≥18 years between 2012 and 2017.

#The proportions were calculated after extrapolation of the number of users to the number of users of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands within the corresponding calendar year; in 2012, data were available from 1608 community pharmacies (81% of all community pharmacies), in 2013 data from 1681 pharmacies (85% of all community pharmacies), in 2014 data from 1732 pharmacies (88% of all community pharmacies) in 2015 data from 1774 pharmacies (90% of all community pharmacies), in 2016 data from 1806 pharmacies (91% of all community pharmacies) and in 2017 data from 1765 pharmacies (89% of all community pharmacies).

aNitrofurantoin, fosfomycin or trimethoprim.

bCiprofloxacin (first choice in 2017), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (second choice in 2017) or co-trimoxazole (third choice in 2017).

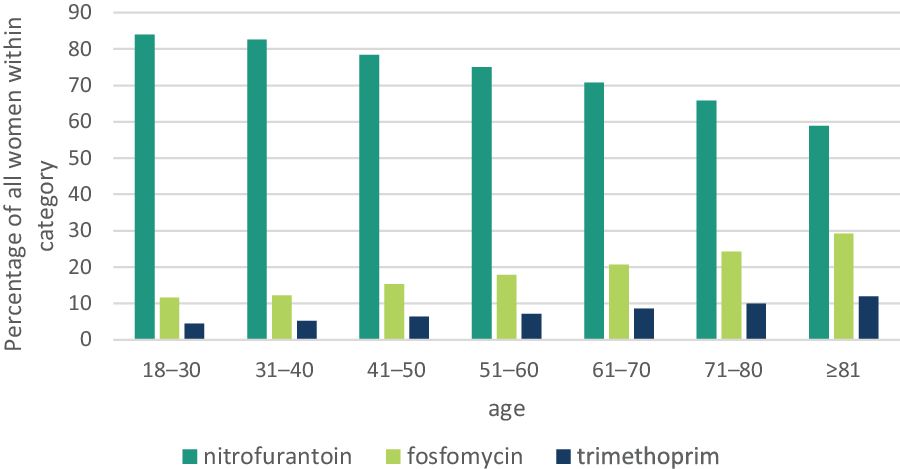

Figure 3 shows the users of uncomplicated UTI antibiotics in 2017, stratified for age categories. Within the two youngest age categories, from 18 to 30 and 31 to 40 years old, dispensing of nitrofurantoin was highest (91.0 and 90.1%, respectively), whereas, within the oldest age category (> 80 years old), only 73.8% were dispensed nitrofurantoin. Fosfomycin dispensings increased from 12.4% in the youngest age category to 36.7% in the oldest age category. Trimethoprim dispensings increased from 4.8% in the youngest age category to 14.9% in the oldest age category.

Figure 3. Percentages# of users of the first, second and third choice guideline antibiotics for acute cystitis treatmenta in women ≥18 years, stratified for age categories in 2017

#The proportions were calculated after extrapolation of the number of users to the number of users of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands in 2017; in 2017, data were available from 1765 community pharmacies (89% of all community pharmacies).

aNitrofurantoin, fosfomycin or trimethoprim.

Proportions of women who received an antibiotic dispensing for febrile UTI within 14 days after an uncomplicated UTI antibiotic also increased with older age (Figure 4). In the oldest age category, the use of ciprofloxacin was highest at 6.6% of all users, followed by 3.8% that were treated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. In women between 18 and 30 years old, dispensing for febrile UTI was lowest; 1.4% of these women were treated with ciprofloxacin and 1.0% with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.

Figure 4. Percentages# of all women with at least one antibiotic for complicated UTIb within 14 days after a guideline antibiotic for uncomplicated UTIa, stratified for age categories in 2017

#The proportions were calculated after extrapolation of the number of users to the number of users of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands in 2017; in 2017, data were available from 1765 community pharmacies (89% of all community pharmacies).

aNitrofurantoin, fosfomycin or trimethoprim.

bNiprofloxacin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or co-trimoxazole.

Discussion

The changes in recommendations for the drug preference in treating UTI within the GP guideline in 2013 showed corresponding changes in dispensing data. This was mainly pronounced in women receiving fosfomycin, which became a drug of the second choice in the revised guideline. Corresponding to the new guideline recommendations, increased use of fosfomycin was mainly at the expense of trimethoprim, which had changed ranks with fosfomycin. Nitrofurantoin, which remained the first choice antibiotic in the guideline update, was the most preferred antibiotic for uncomplicated UTI.

In 2013, the user number of fosfomycin increased from 61.3% to 64,831, twice the increase from 2011 to 2012. In 2014, the increase in the user number of fosfomycin was 56%, but in 2015, the increase in the user number was 23%. The use of fosfomycin was already increasing before the 2013 review of the guideline. According to SFK (oral communication), the user number of fosfomycin in 2008 was 14,928, which increased, with 20–30% yearly, to 40,187 in 2012. This is not surprising as guidelines often follow what is actually already happening in practice. There were already reports that showed increasing antibiotic resistance against trimethoprim and physicians started to prescribe fosfomycin when literature reviews suggested its effectiveness. Inclusion in the guideline as the second choice, however, gave the final boost not only relatively, but also in the absolute number of fosfomycin users. Because of the increase in 2013, the revision year of the guideline, and also that in 2014 were twice the increase in 2012 and in the years before, we regarded this increase as caused by the changes in the guideline.

For subsequent antibiotic treatment in febrile UTI, ciprofloxacin use increased as the newly advised first choice at the expense of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid dispensings. Proportions of women with an antibiotic for febrile UTI within 14 days after an uncomplicated UTI guideline antibiotic were low. Moreover, the proportion of women on whom treatment for unresponsive UTI was started remained stable over the study period. Thus, the increased use of fosfomycin did not seem to imply more subsequent antibiotic UTI treatment compared to nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim, suggesting a comparable effectiveness. However, more research may be needed to unambiguously determine the effectiveness of fosfomycin in UTI treatment as a five-day nitrofurantoin course for uncomplicated UTI treatment was shown to lead to a better cure after 28 days of follow-up compared to a single dose of fosfomycin (Datta and Juthani-Mehta, Reference Datta and Juthani-Mehta2018; Huttner et al., Reference Huttner, Kowalczyk, Turjeman, Babich, Brossier, Eliakim-Raz, Kosiek, Martinez De Tejada, Roux, Shiber, Theuretzbacher, Von Dach, Yahav, Leibovici, Godycki-Cwirko, Mouton and Harbarth2018a; Reference Huttner, Leibovici and Harbarth2018b; Vallee and Bruyere, Reference Vallee and Bruyere2018). Nitrofurantoin remained the first choice because it causes less bacterial resistance compared to other antibiotics. In the Netherlands, in 2017, resistance levels of E coli for nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin in selected GP patients were below 2% versus 24% for trimethoprim (Greeff and Mouton, Reference Greeff and Mouton2019). Resistance may be underestimated in the GP practice, since cultures are usually only performed after failure of initial therapy or for a febrile UTI. Moreover, there is a concern of increasing resistance for fosfomycin with widespread use. A study in Israel showed an increase of fosfomycin resistance levels of E.coli from 20.7% in 2015 to 30.9% in 2016; and of 17.6% in patients 51 years and younger versus 30.0% in older patients (Peretz et al., Reference Peretz, Naamneh, Tkhawkho and Nitzan2019). Consequently, the effectiveness of fosfomycin in UTI treatment has to be monitored further.

A recent review stated that in postmenopausal women, the choice of UTI antibiotics should involve efficacy, underlying patient health conditions, and side effects (Jung and Brubaker, Reference Jung and Brubaker2019). Nitrofurantoin is an appropriate first-line agent with known efficacy and minimal potential for collateral damage. Although nitrofurantoin remained the most dispensed antibiotic for all age categories, the proportions of nitrofurantoin users were lower in the older age categories, with higher proportions using fosfomycin and – to a lesser extent – trimethoprim. From dispensing data, we cannot elucidate the prescribers’ considerations for a higher preference of fosfomycin and trimethoprim in older age categories. Possibly, prescribers preferred the ease of use of a single dose uncomplicated UTI treatment such as fosfomycin because of easier compliance in a population with potentially more drugs with chronic usage (Jung and Brubaker, Reference Jung and Brubaker2019; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Fischer, Molino, Orav, Theiler, Meyer, Fischler, Gagesch, Ambuhl, Freystatter, Egli and Bischoff-Ferrari2020). Another reason for choosing an alternative to nitrofurantoin may have been drug shortages, which in the Netherlands for sustained release nitrofurantoin have occurred, at least for a limited number of months in 2013, 2015 and 2017 (KNMP), Although direct release nitrofurantoin always was available, this alternative needs four daily dosages. This dosage regimen may hamper adherence, especially in cognitively impaired elderly patients, and may have further stimulated switching to the more user-friendly one-off fosfomycin daily regimen.

Prescribers may have also chosen to avoid nitrofurantoin in elderly patients as nitrofurantoin is contraindicated with impaired renal function. According to a number of studies, this is only the case in seriously impaired renal function (eGFR < 30 mL/min) (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Gandhi, Mcarthur, Moist, Jain, Liu, Sood and Garg2015; Hoang and Salbu, Reference Hoang and Salbu2016). A recent study, however, showed that in eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min treatment with fosfomycin or trimethoprim for uncomplicated UTI was associated with more clinical failure than treatment with nitrofurantoin, while in eGFR < 60 mL/min nitrofurantoin was associated with more clinical failure than fosfomycin. Accordingly, renal function, if known, could be considered in the clinical decision-making for uncomplicated UTI treatment (ten Doesschate et al., Reference Ten Doesschate, Van Haren, Wijma, Koch, Bonten and Van Werkhoven2020).

The number of women, 18 years and older, with uncomplicated UTI in absolute terms increased between 2012 and 2017, but the increase can most likely be attributed to demographic developments. The total number of all women in the Netherlands in 2012 was 8,447,477, which increased by 158,928 up to 2017. During these years the mean age increased from 41.5 to 42.5 years (CBS, 2020). We hypothesise that this slight increase can be attributed to the ageing of the female population and the fact that older women more frequently have UTI.

Overall, uncomplicated UTI treatment was mainly initiated by GPs, which corresponds with the Netherlands’ policy for UTI to mainly be treated in primary care.

Within the three UTI guideline drugs, proportions of starters with a GP prescription were comparable. Nitrofurantoin remained the most preferred UTI antibiotic in starters during the study period and the increase of fosfomycin starters was mainly at the expense of trimethoprim.

Stratification for age categories in 2017 showed that the proportions of women with subsequent antibiotic treatment for febrile UTI increased with age. As this might have been due to treatment failure of the UTI guideline antibiotics, their effectiveness in the elderly should be monitored.

Compared to studies from other countries, the changes in antibiotic preferences in the UTI guideline in the Netherlands quickly corresponded with changes in UTI antibiotic prescriptions. Studies in New Zealand (Gauld et al., Reference Gauld, Zeng, Ikram, Thomas and Buetow2016) and the US (Grigoryan et al., Reference Grigoryan, Zoorob, Wang and Trautner2015; Durkin et al., Reference Durkin, Keller, Butler, Kwon, Dubberke, Miller, Polgreen and Olsen2018) reported poor GP adherence to recommended uncomplicated UTI prescribing guidelines. Percentages of patients treated with fluoroquinolones for uncomplicated UTI varied from 20% in New Zealand to 50% in the US, and percentages of patients treated with nitrofurantoin varied from 14% to 35%. The quickly implemented changes in the Netherlands may show a high trust of the GPs in this country to their guidelines and also reflect a good communication in guideline changes and effort for guideline implementation. In the Netherlands, a study on the implementation of Dutch GP guidelines showed that the most preferred implementation strategy by GPs were interactive small group meetings (84% rated this as much or very much encouraging), audit and feedback (53%), organisational interventions like changes in the practice setting (50%) and the use of local opinion leaders (50%) as methods for improving guideline adherence. In the Netherlands, GPs and pharmacists have regular pharmacotherapeutic audit meetings in which guideline changes are discussed (de Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Tromp, Blijleven and De Jong-Van Den Berg1999; Muijrers et al., Reference Muijrers, Knottnerus, Sijbrandij, Janknegt and Grol2003). Moreover, in the audit meetings, agreements for improvement are made and subsequently monitored (Teichert et al., Reference Teichert, Van Der Aalst, De Wit, Stroo and De Smet2007). This complies with the recommendations of a study in the UK to implement a national programme of training and accreditation for medicines optimisation pharmacists (Croker et al., Reference Croker, Walker and Goldacre2019). Furthermore in the Netherlands, guideline recommendations are implemented in the electronic prescribing systems, which also may have contributed to quick changes in prescribing behaviour (Lugtenberg et al., Reference Lugtenberg, Burgers, Han and Westert2014).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that dispensing data from a majority of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands was at our disposal. The antibiotics under investigation were available by prescription only; thus, the medication was completely covered by our database.

A limitation of this study is that we did not have information on the diagnoses and the outcome of treatment. On the other hand, the study drugs for uncomplicated UTI are specific for this indication and thus misclassification is unlikely.

Additionally, we were not able to distinguish nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim use for prophylactic use from acute UTI treatment. Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis for 6–12 months reduces the rate of UTI during prophylaxis when compared to placebo. If women with continuous prophylaxis have a recurrence the guideline advises treatment with one of the other guideline antibiotics for uncomplicated UTI. In a period of 12 months, therapeutic use also often overlaps with prophylactic use because (1) continuous antibiotic prophylaxis for 6–12 months reduces the rate of UTI during prophylaxis when compared to placebo and (2) prophylaxis does not appear to modify the natural history of recurrent UTI and most women revert back to their previous patterns of recurrent UTI once prophylaxis is stopped (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Huertas, Pereiro, Sanfelix, Gosalbes and Perrota2004; Kranjcec et al., Reference Kranjcec, Papes and Altarac2014). In spite of that, we may have mistaken nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim use for UTI treatment instead of prophylaxis. On the other hand, we do not have any reason to assume that this misclassification would be differential during the years of our study period, and thus we do not expect bias for the comparison of the percentages of drug users during the years. However, should the user numbers of nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim be overestimated, then the estimation of fosfomycin user proportions within all users of UTI treatment might be underestimated.

In our cross-sectional study design, the starters consisted of first-time starters and women that switched from another guideline antibiotic within the same year. On the other hand, we do not expect any bias from comparisons of switching between uncomplicated UTI guideline drugs.

We assumed that a dispensing of ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, or co-trimoxazole within 14 days after an uncomplicated UTI antibiotic indicated progression to febrile UTI, but these antibiotics may have been used for multiple indications. By only including the use of these drugs within a 14-day period after dispensing one of the three uncomplicated UTI guideline antibiotics, we minimised the likelihood that these antibiotics were prescribed for other indications, but this cannot be completely excluded. As ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid are used for many different indications, dispensing data did not allow us to analyse the proportion of women with uncomplicated UTI that received these antibiotics as initial medication. Because ciprofloxacin was first choice for treatment of complicated UTI, we expect GPs to prefer this antibiotic, comparable to the treatment for unresponsive UTI, when they chose to prescribe a non-guideline antibiotic for uncomplicated UTI. Moreover, a recent study on the use of antibiotics in the Netherlands compared to Germany showed that the overall use of ciprofloxacin in the Netherlands is very limited and much lower than the uncomplicated UTI antibiotics studied (Gradl et al., Reference Gradl, Teichert, Kieble, Werning and Schulz2018). Consequently, while ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid may sometimes have been prescribed as initial treatment for uncomplicated UTI, the proportion of women that received these drugs as initial treatment must be negligible.

Summary and conclusion

This study shows substantial changes in UTI prescribing behaviour after UTI guideline changes in 2013. This may have been facilitated by clear guideline recommendations and a broad implementation strategy with regular pharmacotherapeutic audit meetings and incorporation of the GP guideline recommendations in the electronic prescribing systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Manon Verkroost from SFK and Petra Overbeek from Laboratorium der Nederlandse Apotheken for their information on dispensings before 2012 and shortages of nitrofurantoin respectively.

Authors’ Contribution

All authors have made a substantial, direct, intellectual contribution to this study.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The Institutional Review Board of SFK approved this study. Use of observational data in descriptive studies in the Netherlands is not considered to be an interventional trial, according to Directive 2001/20EC of Dutch legislation. Therefore, the study protocol did not need to be submitted to a medical ethics committee for approval.