Introduction

In the early 2020s, it is well established that the proliferation of social media has provided new opportunities for musicians to connect with their audiences and diversified pathways to recognition and success.Footnote 1 One effect of this is the emergence of a new generation of child musicians whose careers have developed mainly in the digital sphere, sometimes in ways that open onto the global public stage. A prominent example of this is the British-Zulu drummer and multi-instrumentalist Nandi Bushell, who was born in South Africa in 2010 and is growing up in the UK. Her parents first uploaded videos of her drumming to YouTube in January 2017, when she was six years old. Over the following years, Bushell developed a strong presence on social media, including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, performing mainly within the genres of rock, hard rock and metal. Bushell has been endorsed by major instrument manufacturers including Fender, Ludwig Drums, Vic Firth and Zildjian, and her achievements as a musician have been recognised by the international music press: she was featured in Rolling Stone magazine's special issue on ‘Women shaping the future’ in March 2021 and appeared on the cover of Modern Drummer magazine in June that same year – as the youngest person ever (Molenda Reference Molenda2021a).

This article investigates the early career of Nandi Bushell as a point of entry for understanding children's participation in mainstream popular music culture and the broader public sphere. Recent decades have seen the gradual blurring of the lines between children's musical cultures and popular culture at large (Bickford Reference Bickford2020; Hansen Reference Hansen2020; Warwick and Adrian Reference Warwick, Adrian, Warwick and Adrian2016), something that raises new questions concerning prevailing trends in children's socio-musical practices, child musicians’ status in popular music discourse and children's cultural and political influence. In order to address such issues, we explore Bushell's social media presence, creative output and public reception in relation to three interrelated themes: the functioning of social media and the music press as arenas for the (re)negotiation of ideas about child prodigy; child musicians’ political activism; and the role of adult ‘mentor-fans’ in sponsoring girls’ participation in rock culture. In grappling with the complexities of these themes, we place a particular emphasis on querying how dominant conceptions of girlhood inform the press coverage of Bushell's music and social media output, as well as on examining her highly visible relationships with established male rock artists serving as mentors, fans and industry brokers. This allows us to critique the dynamics of girls’ standing in contemporary rock music discourse and pursue new avenues for understanding the contributions of girls’ musicianship to popular culture more broadly.

Girl musicians have generally received little attention in music criticism and the music press, at least historically speaking. Indeed, the musical contributions of girls have historically been dismissed or overlooked (Marsh Reference Marsh2018; Pecknold Reference Pecknold, Warwick and Adrian2016; Warwick Reference Warwick2007), and girls’ visibility in popular music discourse has largely revolved around portrayals of them as hysterical fans and undiscerning consumers (Dougher and Pecknold Reference Dougher and Pecknold2016, p. 407). Such tropes belie the rich relationships that girls create with music, both as audiences and as artists, and are bound up with longstanding hierarchies and prejudices related to cultural associations between gender and genre. Rock music especially has long been established as a particularly serious, ‘authentic’ and valuable form of music, and – despite the evident diversity of its performers and audiences – the genre has been most prominently associated with White, straight cis men, to the extent that the contributions of women and girls, and especially Black women and girls, have been substantially marginalised (Coates Reference Coates and Whiteley1997, Reference Coates2003; Mahon Reference Mahon2020).Footnote 2 In light of this background, we aim to explore what Bushell's early career can tell us about the contradictions and ambiguities that characterise the status of girl musicians in the present-day landscape of rock music. This involves addressing Bushell's diverse interactions and relationships with her fans and fellow musicians, her use of music to address and bring attention to topical issues in culture and society, and the social politics of prodigy discourse and musical genre categorisation. Intentionally broad in its scope, the article adds to existing scholarship on girls’ participation in the popular music sphere (e.g. Blue Reference Blue2013; Dougher Reference Dougher, Warwick and Adrian2016; Pecknold Reference Pecknold, Warwick and Adrian2016, Reference Pecknold2017; Stimeling Reference Stimeling, Pecknold and McCusker2016; Warwick Reference Warwick2007) and explores some of the ways in which notions of girlhood as a cultural identity are negotiated by young artists and their (often adult) audiences in relation to musical genre boundaries.

Bushell's social media presence, prodigy discourse and rock star mentor-fans

Nandi Bushell's rise to fame and public recognition at a young age resembles the career trajectories of other young musicians who first garnered attention on social media. In his work on tween pop – the musical expressions and practices that straddle the line between children's (consumer) culture and the broader popular music sphere – Tyler Bickford (Reference Bickford2020, p. 141) asserts the significance of the emergence of social media platforms in the late 2000s for the astounding and seemingly sudden success of young pop artists such as Justin Bieber and Taylor Swift. Bushell's example reaffirms the significance of social media to young artists’ career development in the present day, but certain unique aspects of her career suggest that different conceptions of genre, gender and age are important variables in the networks that social media help artists access.

In Bushell's early career, social media posts represent both the primary means by which she distributes her music, her main means of interaction with fans and fellow musicians, and one of the focal points of the journalistic discourse surrounding her. Indeed, a new video posted to Bushell's social media has often generated headlines in the mainstream music press (see, for example, Lavin Reference Lavin2022). The cultural attention directed towards Bushell's video performances, in lack of more official releases, has tended to emphasise the home- and family-oriented settings that are prominently displayed in these videos and on her social media. Much of Bushell's social media content offers what Bickford has described as ‘a vision of intimate one-to-many and many-to-many communication that seems to overcome barriers between public and private and allows [young artists’] public success to be presented as though it is embedded within comfortable family domesticity’ (2020, p. 141). Most of her videos are recorded in her home rehearsal space and many of them feature the other members of her family. Given that Bushell was only six years old when she first started uploading videos to YouTube, it is no surprise that her parents were involved in establishing her social media presence and continue to play a key role in managing it. While many young performers are capable of navigating social media on their own, parents often have an initiating role in setting up their children's accounts and uploading videos of them (de Mink and McPherson Reference de Mink, McPherson and McPherson2016, p. 434). In Bushell's case, the fact that her father, John Bushell, got her started on the drums, records her video covers and manages her social media accounts has been a frequent topic in interviews (Doherty Reference Doherty2021; Shteamer Reference Shteamer2021). In some interviews, Bushell's father also answers certain questions concerning video production and his daughter's social media presence (see Molenda Reference Molenda2021b). While highlighting the significance of family as a support network for young artists, the conspicuous focus on Bushell's father in some media coverage could potentially reproduce discourses that treat successful women and girl artists as owing their success to men in their lives, an issue we address in more detail towards the end of this article.

The high visibility of home and family in Bushell’ social media posts, as well as in the general media discourse surrounding her, mitigates tensions between her global public exposure and traditional conceptions of childhood as something domestic, innocent and fun. Even as Bushell is gaining global attention as a musician, then, the emphasis placed on the notion that she is also a ‘normal’ girl is integral to her status as a child prodigy. Responses to Bushell's music have regularly highlighted the apparent mismatch between her age and her musical ability, participating in a ‘prodigy discourse’ (Bickford Reference Bickford2020, p. 145) that is deeply implicated in cultural constructions of children's musical authenticity, skill and talent.

Prodigy discourses function to connect musical and cultural values, and in Bushell's case evaluations of her musicianship often shift quickly to evaluations of her personality, communication of emotions and other intangible, affective qualities. One prominent example of this is found in Michael Molenda's editorial for the issue of Modern Drummer that featured Bushell on the cover, in which he describes how the young drummer's social media content contrasts with that of other young musicians who ‘possess frightening technique’ but post videos that are ‘ridiculous and inane’, devoid of aesthetic or artistic value:

But that silly stuff is a far different thing than what Bushell and other instrumentalists like her are doing […] Bushell has become a significant and colossal evangelist for drums, drumming, rock music, multi-instrumentalists, music education, and the joy and accomplishment of playing an instrument. She has inspired countless people of all ages – especially during the global pandemic – to pick up drumsticks or a guitar or bass or keyboards and get down to the blissful business of making music. Her authentic, over-the-top enthusiasm is catching. Every time I watch one of her videos, I feel compelled to sit behind my kit, or play some guitar or bass. I've talked to people young and older who credit Bushell with getting them off the couch and playing again, or starting to play for the first time. It doesn't hurt that celebrities are also enchanted by Bushell's energy, and have helped the cause by promoting her. […] [A]ffecting an audience is paramount to what [musicians] all do. On that score, Bushell has proven herself to be a total badass. (Molenda Reference Molenda2021a)

As prodigy discourses go, this is somewhat unusual. Molenda's assessment is not based on Bushell's drumming technique or skills but the enthusiasm and joy she exudes when playing, and he thus appears to diverge from the criteria by which Modern Drummer has conventionally evaluated featured artists. Molenda (Reference Molenda2021a) seems to acknowledge this when he notes that it would have previously been inconceivable and ‘all kinds of wrong’ to feature a pre-teen drummer on the cover of the magazine, suggesting that it is the ‘evolution of media culture’ and the changing circumstances of the music business that have made it possible for young performers to now have a monumental impact on audiences, other musicians and the music industry as a whole. It is significant that the evaluative terms Molenda uses are neither technical nor aesthetic, but social: Bushell's unique talent is described explicitly in terms of transferring positive emotions to others, inspiring them and inviting them to participate in the musical project.Footnote 3 Molenda's emphasis on celebrities’ enchantment with and support of Bushell also indicates, we suggest, that the specific way that prodigy status is ascribed to Bushell in the music press is closely entwined with how she is seen to interact with her fans – and, importantly, who these fans are.

From early on in her career, Bushell's social media performances caught the attention of several high-profile musicians. Drummer of The Roots, Questlove, was impressed by Bushell's early videos and sent her a drum kit he had designed specifically for kids (Doherty Reference Doherty2021). In 2019 Lenny Kravitz saw Bushell on Instagram and invited her to meet and jam with him at the O2 arena in London, subsequently gifting her both a drum kit (with Nate Smith) and an electric guitar. In November of that year Bushell's drum cover of Nirvana's ‘In Bloom’ (1991) went viral, gaining ten million views on Twitter in a single week (Jones Reference Jones2019). Picking up other instruments over the course of 2020, including guitar, bass guitar, piano and saxophone, Bushell started posting video covers of rock songs with herself performing all parts. One such multi-instrument cover of Muse's ‘Plug in Baby’ (2001) prompted the band's lead singer and guitarist, Matt Bellamy, to send her one of his signature guitars as a sign of his appreciation for her work.

Similar examples of Bushell's connections to adult artists abound, but the most visible of these has been her extended interactions with Dave Grohl, the front man of the Foo Fighters and, during the early 1990s, the drummer of Nirvana. The two first crossed paths in August 2020, when Bushell posted a drum cover of the Foo Fighters’ song ‘Everlong’ (1997) on her YouTube channel and challenged Grohl to a drum-off. Grohl accepted the challenge and a drum battle ensued, playing out through a series of online videos. Grohl conceded defeat in November 2020 (Shaeffer Reference Shaeffer2020), proceeding to invite Bushell to join the Foo Fighters for an encore of ‘Everlong’ during an arena show the following year. Video footage of the live performance went viral, which precipitated the song's reappearance on several Billboard rock music charts (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2021) and generated further media attention for Bushell. While the relationship between Bushell and Grohl illustrates how social media can provide child musicians with new opportunities for connecting with fans and fellow musicians on a global scale, questions concerning the conspicuous role that Grohl and other famous rock stars have played as cultural intermediaries in Bushell's early career open onto complex debates about how children are positioned in the contemporary field of popular music. In similar terms as Molenda, Grohl has offered high praise of Bushell framed in terms of ‘meaning’ and inspiration: ‘If you want to see the true meaning of rock & roll, watch Nandi play the drums. That is as inspiring as any Beatles record, any Zeppelin record, any AC/DC record, any Stones record’ (Grohl quoted in Martoccio Reference Martoccio2021). This statement reinforces the decentring of skill and technique in the particular conception of child prodigy that is most clearly associated with Bushell in the music press.

Whereas technique and skill are the traditional measures of an instrumentalist's worth, also within child prodigy discourse (de Mink and McPherson Reference de Mink, McPherson and McPherson2016; Gagné Reference Gagné, MacFarlane and Stambaugh2009), Molenda's and Grohl's descriptions of Bushell recalibrate the set of criteria by which a (child) musician's achievements are evaluated. Such a recalibration is apparent also in other media coverage of Bushell (e.g. Doherty Reference Doherty2021; Jones Reference Jones2019),Footnote 4 which often emphasises her enthusiasm for playing music and highlights the potential of this enthusiasm to inspire others. We argue that the de-emphasis on technique and skill is part of a broader reception of Bushell in which the intersection of social media, genre and gender interrupts certain conventional frameworks for evaluating spectacular child musical performances.

In recent years child musical prodigy has been an especially common discourse on YouTube (de Mink and McPherson Reference de Mink, McPherson and McPherson2016) and other social media, and celebrated child musicians now more frequently cross over into broader celebrity and public awareness. Prodigy discourses are commonly framed in terms of sociocultural identities as much as or more than decontextualised musical ability (Bickford Reference Bickford2020, p. 148). Social media have often been framed as connecting young artists directly to their ‘fans’, building relationships with audiences directly rather than through the bureaucratic structures of music labels and their A&R wings. An earlier generation of artists, most notably celebrity singers such as Justin Bieber and Taylor Swift, were widely understood as using social media to connect directly to listeners who shared their identities, especially along axes of age and gender, and it was their unusual capacity to elicit broad public identification with young audiences that was commonly seen as the key element of these artists’ exceptional musical talent.

Like Bieber and Swift, social media also allowed Bushell more direct connections with audiences that were key to gaining wider exposure. But rather than connecting primarily to listeners who share identity markers of age, gender or race, social media allowed her to make contact with established adult musicians, who then served as cultural brokers for her. This appears in some ways as more similar to ‘crossover’ singers such as Jackie Evancho and Angelina Jordan, whose online and social media-based performances in genres other than pop (classical and jazz, respectively) found their most enthusiastic listeners primarily among adults, specifically adult men (Gorzelany-Mostak Reference Gorzelany-Mostak, Warwick and Adrian2016; Merkelbach Reference Merkelbach2022).

Prodigy discourses are frequently framed in terms of awe, wonder or astonishment (Feldman and Morelock Reference Feldman, Morelock, Steinberg and Kaufman2011). For tween pop stars like Bieber and Swift, those discourses focused primarily on the young artists’ uncanny ability to connect with young listeners in a way that adults presumptively could not, highlighting their incredible commercial success as a result. For classical and jazz crossover artists like Evancho and Jordan, in contrast, prodigy discourses emphasised the ‘innocent’, and frequently ‘angelic’, qualities of the singers in parallel with their virtuosically ‘mature’ performances of aesthetically privileged musical repertoires, highlighting adult audiences’ transcendent listening experiences (Gorzelany-Mostak Reference Gorzelany-Mostak, Warwick and Adrian2016; Merkelbach Reference Merkelbach2022). Both discourses foregrounded the age of the performers, and they were also keyed strongly to genre, with pop being understood as youthful and jazz and classical as mature. Significantly, in both of these models the artists’ musical ability was important, but their reception emphasised non-musical factors related especially to the perception of the artists’ age and ideologies about the nature of childhood.

Bushell does not fit either of these models perfectly. Much more than Evancho and Jordan, her social media success narrative very much involved developing specific personal connections with other individuals through social media, but unlike Bieber and Swift, those connections were most visibly with established adult musicians, rather than to young audiences.Footnote 5 Professional musicians’ admiration for Bushell has been placed front and centre in the music press, as evidenced by headlines such as ‘This 10-year-old drummer stole Dave Grohl's heart – and ours, too’ (Doherty Reference Doherty2021) and ‘Who is Nandi Bushell? The drummer aged 11 who has rock stars for fans’ (Bedirian Reference Bedirian2021). Bushell has indeed received much attention from fellow performers and formed sustained relationships with several of them. Artists such as Lenny Kravitz, Annie Lennox, Tom Morello, Questlove and Sheila E. have frequently commented on her social media posts. And others, including Bring Me the Horizon, Fatboy Slim, Linkin Park, Metallica, Red Hot Chili Peppers (Flea and Chad Smith), Rush (Alex Lifeson), Slipknot (Corey Taylor and Jay Weinberg), Tool, and many more, have re-posted or responded to her video covers of their songs. More than simply praising her, many of these adult artists have interacted with her directly through social media. Furthermore, as we have already noted, several of these artists have invited her to meet them, jam with them or perform on stage with them, and others have shown support for her with gifts of equipment and instruments. For Bushell, then, social media have provided significant opportunities to network and collaborate with established music industry professionals. What's more, the public relationships Bushell developed with (primarily male) adult rock stars early on in her career – reported widely by the mainstream music press – were integral to growing her visibility among broader international audiences, while also contributing significantly to those adult artists’ cultural relevance and popularity.

What is the cultural significance of a host of well-established rock stars showing public support of and appreciation for a pre-teen girl drummer? We call these industry sponsor figures ‘mentor-fans’, to highlight the bidirectionality of their relationships with Bushell. While a significant part of their role is as sponsors or brokers, helping Bushell enter and navigate the music industry, they also perform their relationship to Bushell in terms of appreciation and admiration – as ‘fans’. One might view this dynamic as a reversal of prevailing popular music discourse, wherein girls and women have primarily been assigned the role as undiscerning fan and their contributions as musicians and songwriters have been largely overlooked (Coates Reference Coates2003; Mahon Reference Mahon2020; Pecknold Reference Pecknold, Warwick and Adrian2016; Warwick Reference Warwick2007). Notably, however, the partial decentring of musical skill that occurs in much media coverage of Bushell attenuates this potential reversal by attributing her accomplishments and popularity to qualities that are familiar within conventional understandings of girlhood, such as joy, enthusiasm and innocence. Similarly, while rock music has its own traditions of valuing musicianship and even virtuosity, it most highly privileges authenticity, which is front and centre in Molenda's, Grohl's and others’ evaluations of Bushell.

So, while Bushell's career parallels those of other young artists in the twenty-first century, its nuance and specificity help to identify the boundaries between different conceptions of childhood and gender that circulate in relation to different genres and media. As a multi-instrumentalist, Bushell works largely outside the ideologies of vocal performance that constrain the reception of girls’ voices in pop and other genres (Pecknold Reference Pecknold, Warwick and Adrian2016; Warwick Reference Warwick, Bennett and Waksman2015). Performing primarily in rock (broadly conceived), she is also freed from certain of the expectations of femininity and innocence that structure both pop music and classical vocal crossover performance.Footnote 6 That, in turn, positions her neither as the child who connects authentically with other children through shared identities and emotional experiences, nor the child who performs idealised angelic innocence for an adult gaze. Instead, Bushell's unique combination of age, gender and genre positions her within another more recent construction of musical childhood, namely ‘girls’ rock’.

Girls’ rock

Since the riot grrrl movement of the 1990s, an influential tradition linking girlhood and rock music has become, if not mainstream, then at least familiar and institutionalised. While girls’ rock discourses are diverse and complex, we identify some common values and structures that help make sense of the centrality of adult mentor-fans to Bushell's reception and presence in the public sphere. While part of an insurgent, explicitly feminist intervention, girls rock discourses in the 1990s and 2000s linked up with an increasingly mainstream discourse of ‘girl power’ that positioned girls and girlhood as a key site for feminist intervention,Footnote 7 while also prioritising youth in mainstream post/feminist trends. Girls’ rock discourses frequently emphasise rock as a venue for girls’ cultivation of an individual voice and their practice of self-expression. And, as an explicitly feminist tradition, girls’ rock discourses also emphasise supportive mentoring relationships across generations.

One key site of the institutionalisation of girls’ rock discourse is the global Girls Rock Camp movement beginning in the early 2000s, inspired by the Rock ’n’ Roll Camp for Girls in Portland (see Marsh Reference Marsh2018; Pecknold Reference Pecknold2017). As Sarah Dougher (Reference Dougher, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 191) points out, the genre distinction between rock and pop is a central focus of girls’ rock camps’ formal and informal curricula, with rock being positioned as a site of authentic expression. This is notable because rock and its prevailing paradigm of authenticity continue to be highly masculinised.

Notwithstanding the diversity of gendered discursive qualities in rock music, the genre remains associated with a narrow range of identities – primarily those that are coded White, male and heterosexual (see Coates Reference Coates and Whiteley1997; Mahon Reference Mahon2020). Jacqueline Warwick elaborates on this discourse:

In rock culture, where the ideology of authenticity is powerful, a star must represent rebelliousness, defiance of convention, and disdain for commerce in favor of art for art's sake; and these notions are most plausibly personified by a white, male instrumentalist […] whose devotion to ‘sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll’ is manifest. (2015, p. 343)

Even if such expectations are far from strict or complete, they do continue to frame the performance practices and audience cultures of adults and children alike. This does not mean that traditional power structures in rock music and popular culture more generally are not being challenged, though. As Dougher (Reference Dougher, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 192ff) and Charity Marsh (Reference Marsh2018, p. 90ff) both suggest, rock music is increasingly understood as an empowering space for girls to develop their own voices, confront inequality in the music industry and oppose narrow stereotypes of girlhood.

The girls’ rock tradition is now well established and influential, although its concepts circulate more through educational institutions like music camps, feminism and parenting than through media and the music industries. And while girls’ rock discourses emphasise girls’ voice, agency and empowerment, they are nonetheless strongly motivated by adults’ ideas about and concern for girls. For example, as educational organisations, girls’ rock camps position girls in a developmental location in relation to adult mentors. That contrasts distinctly both with the tween pop stars’ celebrated connections with other children and with the crossover jazz and classical singers’ performance for a fetishising adult gaze. In a sense, girls’ rock explicitly makes space for benevolent if also sometimes paternalistic adult mentorship.

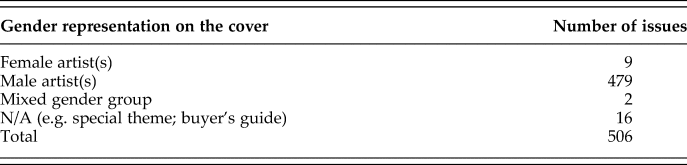

Bushell exemplifies the expansion of girls’ rock discourse into mainstream popular culture, as is illustrated by her many appearances in the international music press. Her aforementioned appearance on the cover of Modern Drummer magazine is a pertinent example of the cultural significance of the public attention she has received. Bushell is one of only ten female drummers to be featured on the cover of Modern Drummer from its inception in 1977 until 2021. Of the 506 issues released between 1977 and 2021, eleven have featured women on the cover (which includes instances where women have shared the cover story with men; see Table 1). For comparison, Neil Peart of progressive rock band Rush appeared on ten of the magazine's covers over the same period. Against this background, Bushell has arguably both claimed new space and increased visibility for girl musicians within mainstream rock music and culture.

Table 1 Representation by gender in Modern Drummer cover features 1977–2021

At the same time, much of the media attention for Bushell is devoted to her relationships with adult musicians specifically, which retain a clear mentoring dimension in girls’ rock discourse even as they develop in a professional, mainstream context. In girls’ rock camps mentors are conventionally women or non-binary people, but the intersection of girlhood and rock as a space of guided development seems to have provided conceptual scaffolding for understanding the engagement between Bushell and established male rock stars as benevolent if paternalistic mentoring relationships. In stark contrast to the credo of ‘sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll’ that has characterised the masculine posturing of many male rock stars since the genre's emergence, Grohl and other male musicians who have publicly supported Bushell seem to embrace roles as supportive father figures eager for a new generation of musicians to follow in their footsteps. While interactions between Bushell and these adult mentor-fans raise questions concerning the power dynamics located at the intersections between age, gender and genre, to which we return towards the end of the article, they also produce actual opportunities for her to develop her musicianship and explore new creative avenues.

This is exemplified by Bushell's first original song, ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ (2021). The song and its accompanying music video are explicitly framed as an activist and political intervention in the ongoing conversation about climate change. They therefore prompt consideration of child musicians’ political agency, provide us with points of entry for shedding further light on the gendered (and genred) complexities of girls’ ‘voice’ and ‘empowerment’ through rock, and highlight the role of visible adult sponsors in legitimating girls’ public activist interventions.

‘The Children Will Rise Up!’: young musicians’ political activism, voice and agency

Common conceptions of childhood as carefree, innocent and fun have historically complicated children's position both within discourses concerning music's political potential and within social movements more generally. Yet even if young musicians and activists, especially girls, have routinely been marginalised and undermined, they have nonetheless found ways to express themselves and assert their cultural and political influence (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Edell, Jones, Luckhurst, Percentie, Warwick and Adrian2016; Hansen Reference Hansen2020). As such, they also contribute to the public (re)construction of girlhood. Further investigation into such processes is a necessary step towards increasing our understanding of ongoing developments in popular music, culture and society.

Bushell has on several occasions shared performances or statements that can be described as explicitly political. For example, she has shown support for the Black Lives Matter movement in various ways. A particularly prominent example of this is a multi-instrument video cover of Rage Against the Machine's ‘Guerrilla Radio’ (1999) that she posted on 1 June 2020. Amid global anti-racism protests following the murder of George Floyd by a US police officer just one week earlier, Bushell attached a home-made ‘BLACK LIVES MATTER’ sign to her kick drum and, in the video caption, called for solidarity in the fight to end racism. Tom Morello (the guitarist of Rage Against the Machine) re-tweeted her post, something that was reported widely in the music press (see Rowley Reference Rowley2020). By covering a band that is well known for their political activism (see LeVan Reference LeVan, Weglarz and Pedelty2013), Bushell capitalised on the group's reputation as protesters and utilised their musical language as a means for raising awareness for one of the most pressing global social challenges at the onset of the 2020s. Furthermore, the public attention Bushell received for the performance increased the visibility of children's participation in social protests and highlighted children's capacity as activists.

As the circumstances of children's culture are changing, so too do children's opportunities to influence their cultural, political and social conditions. This has been demonstrated most persuasively by Greta Thunberg and other young environmental activists, including musicians, who have asserted themselves influentially in the global debate about anthropogenic climate change (see Hansen Reference Hansen2020). Bushell joined this debate when she released ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ in October 2021,Footnote 8 which raises questions concerning children's ambiguous positioning in environmental debates, the social meanings ascribed to girls’ voices, and the possible effects of celebrity endorsements of children's activism and musicianship.

‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ is written by Bushell along with Roman Morello (who was ten years old at the time of the song's release, a year younger than Bushell) and his father, the aforementioned Tom Morello. The song was released in collaboration with Fridays for Future Brazil and England, branches of the School Strike for Climate movement started by Greta Thunberg. Proceeds from the song were donated to the non-profit organisation the SOS Pantanal Institute, which illustrates how child musicians can support environmental causes in economic ways as well as through their aesthetic practices.

The song is characterised musically by a heavy rock style and overall sound reminiscent of that of Rage Against the Machine, something that might be considered unsurprising given Tom Morello's involvement in the songwriting and recording processes. The instrumentation is relatively sparse, consisting of the three main instruments traditionally used by rock bands: bass, drums and electric guitar. The key is A minor and the tempo is around 102 bpm. After a brief opening that places Bushell's drum fills front and centre alongside overdriven power chords on the guitar, the main riff is introduced (approximately 00:11 of the sound recording). The combination of a syncopated element and straight eighth-notes played powerfully on the snare drum and overdriven guitar (with strings muted so that no clear notes ring out) closely resembles a section of one of Rage Against the Machine's most well-known songs, ‘Bulls On Parade’ (1993). The stylistic similarities are prevalent enough that the main riff in ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ serves as an intertextual reference to Rage Against the Machine's general sound and musical style. Granted that the group are widely recognised as political activists,Footnote 9 Bushell's and Roman Morello's use of Rage Against the Machine–esque musical gestures in the opening of ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ embeds the child performers in a tradition of explicitly political rock music and, by extension, serves to sonically reinforce its political message.

The song's environmentalist sentiment is clearly laid out in the lyrics, as in the opening verse: ‘They let the earth bleed to feed their filthy greed/stop polluting politicians poisoning for profit/while they're killing all the trees, now we all can't breathe/as the temperatures are rising, nothing is surviving’. The environmental crisis described in the verse prompts an assertive response in the chorus: ‘The children will rise up/our voices will be heard’. The juxtaposition between the sense of powerlessness in the verse and the commanding call for action in the chorus reflects children's dual positioning in contemporary environmental debates: children tend to be seen as the primary victims of anthropogenic climate change, on the one hand, and as among today's most influential climate activists, on the other (Hansen Reference Hansen2020, p. 6). Both the mainstream media and humanitarian organisations have maintained the common conception that it is the children's future that is at stake in the climate crisis (see, for example, UNICEF 2021). At the same time, children's activism has greatly influenced global political debate on environmental issues, as is evidenced by the widespread media attention for the School Strike for Climate movement.

This dual positioning is mirrored sonically in the ‘Children Will Rise Up!’, specifically in the interplay between children's voices and the powerful rock accompaniment. It is only when Bushell's vocals are introduced (approximately 00:21 of the sound recording) that aural attention is called to the fact that the song is performed by child musicians. Bushell sings in a high register and with a distinctly childlike timbre. She thus intervenes in the fairly traditional heavy rock aesthetic by claiming space for girls’ voices within it. Such a gesture is reinforced in the chorus, when Bushell is joined by a children's choir (approximately 00:40 of the sound recording). A high variance in pitch control and rhythmic precision between the individual voices is in accordance with common expectations of children's choirs. The vocal tracks of ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ therefore make audible children's musical contributions to the recording, in a way that the instrumental tracks do not. The main significance of this lies in how the sonic characteristics of Bushell's lead vocals are likely to complicate the song's activist potential for some listeners.

The complex cultural coding related to voice, childhood and gender is discussed by Jacqueline Warwick and Allison Adrian, who note that the voices of girls and young women often serve as ‘lightning rods for many of our cultural anxieties about authority and power’ (Reference Warwick, Adrian, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 3). Even if notions of ‘voice’ and ‘voicing’ are frequently associated with agency, not all voices are valued equally and the ‘specific sonic character of the young female voice is routinely denied authority’ (Warwick and Adrian Reference Warwick, Adrian, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 3). Indeed, girls and young women who speak up in public debates run a significant risk of being undermined, ridiculed and harassed. This has been demonstrated also in the case of girl musician-activists who intervene in environmental debate (Hansen Reference Hansen2020, pp. 11–13). The common dismissal and distrust of girls’ political opinions can be at least partly explained by Western culture's deeply patriarchal past, which has resulted in girls’ voices – both figurative and literal – becoming devalued as unimportant and contemptible (Warwick and Adrian Reference Warwick, Adrian, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 4).

Bushell's vocal performance simultaneously conforms to and challenges the sonic conventions associated with stereotypes of girls’ voices as ‘whiney’ (Pecknold Reference Pecknold, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 77) and ‘squeaky’ (Warwick and Adrian Reference Warwick, Adrian, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 3). While her voice is high-pitched and characterised by a childlike timbre, her attitude is clearly assertive, authoritative and commanding. In the first verse, for example, this is communicated through the emphasis placed on certain syllables that fall on the downbeat (e.g. ‘poll-U-ting’, ‘POI-son-ing’ and ‘KILL-ing’), as well as by her vocal expression approaching a shout before the transition to the chorus (specifically in the phrase ‘nothing is surviving’, at 00:37 of the sound recording). Another notable moment occurs during the transition between the bridge section and the final chorus: when the sound of a chainsaw disrupts the mellow atmosphere of the bridge – characterised by a softly played jazz-shuffle drumbeat, acoustic guitar and nature sounds (birdsong, insects chirping) – Bushell erupts in a furious roar (approximately 02:39 of the sound recording) that marks a clear break with the sonic clichés of girls’ voices. Overall, Bushell's vocal performance stresses the urgency of the environmentalist message of the lyrics and calls attention to the capacity of the pre-teen girl's voice to intervene in political debate.

The music video, made by John Bushell, combines performance footage, green screen effects and documentary images. Nandi Bushell and Roman Morello are shown playing their instruments in an outer-space environment, with Bushell digitally duplicated and acting as both singer and drummer (see Figure 1). Behind them is a photo montage that provides a visual representation of key themes in the lyrics, showing images of factories, ravaged natural environments and climate change protests. The School Strike for Climate movement is prominently represented in the images, and the video also features an appearance from Greta Thunberg (approximately 03:30 of the music video),Footnote 10 which serves to validate its activist message and potential.

Figure 1. Screenshot from The Children Will Rise Up! (dir. John Bushell, 2021).

Notably, the first voice heard in the music video is not Bushell's but actor Jack Black's, whose performance as the lead character in the blockbuster film School of Rock (2003) made him one of the most evident proponents of bridging the gap between rock music and children's culture. The music video opens with a closeup of Black's face, and in a digitally processed robotic voice he says, ‘in the beginning, there was rock!’ While Pecknold (Reference Pecknold, Warwick and Adrian2016, pp. 85–87) notes that negative discourses about young women singer's voices often emphasise digital processing,Footnote 11 in this case Bushell's seemingly unprocessed, ‘authentic’ childlike voice appears in a strong contrast with Black's extremely processed voice. The video, then, establishes a contrasting relationship between the child performers and their famous adult mentors as, from the outset, one defined in part by ‘voice’. At the conclusion of the song, Black reappears to say, ‘excellent. Your training is complete. Now go and rock the world!’ He thus explicitly frames the performance as a form of education and development (‘training’) rather than as a complete performance in its own right, fitting the video neatly within the mentoring/developmental frame of girls’ rock discourses. Reinforcing this paternalistic developmental framing, Tom Morello also appears on screen during Roman's guitar solo, looming over the two child musicians as he looks at the camera and silently mouths, ‘that's my son!’ before turning his attention to Bushell and headbanging in approval. So, while Bushell's voice is presented as unprocessed and ‘authentic’ in comparison with Black's, that notion of authenticity is also located in a childhood context that still subordinates the young musicians to adults – specifically fathers and father figures.

The final section of the video explores this complicated relation of children to adults in surprisingly precise detail. When the song is over Bushell speaks directly to the camera, addressing adults and children separately and in turn:

I cannot vote but I can raise awareness and protest for climate change. Adults, politicians: stop playing political games with our future. Stop fighting each other! Let's all come together to tackle humanity's biggest problem – before it's too late! Children: Rise up! You can do anything you put your minds to. You can be a real superhero and save the world. Demand your parents to force their government to do better. Your parents have power to make politicians do the will of the people. We need change and we need it now. This is how I'm going to protest. How are you going to protest? Be kind, be loving, be sensible, be respectful, but be powerful! You have a voice! Use it!

Bushell is frank about her lack of a specific kind of agency as a child: ‘I cannot vote’. She exhorts adults and politicians to take action to address climate change. But to her fellow children her assertion of their power is belied by the complex process through which they might implement it: by making demands of their parents who can then make demands of politicians who can then actually take action. While Bushell uses the word ‘power’ to refer to both adults’ direct agency and children's persuasive agency, she ultimately asserts a rather strict division between actions and persuasion, with children's power existing entirely on the side of persuasion. If Bushell acknowledges that she cannot vote, she can ‘raise awareness and protest’. And the summation of her message to children is ‘you have a voice’.

This framing of children's musical activism fits neatly into the girls’ rock framework of ‘empowerment’ and ‘voice’ as the key benefits that rock provides to girls, while perhaps also playing into intensifying cultural expectations of girls to take on social responsibility. As Sarah Projansky has argued, the contemporary media environment increasingly treats girls and girlhood as a ‘spectacle’, a constant object of media attention, in which ‘the convenient figure of the girl … surfaces once again to work through contemporary social issues’ (Reference Projansky2014, p. 11). Relatedly, Jessica Taft argues that the ‘figure of the girl activist’ is increasingly visible in contemporary media because ‘the girl activist savior is defined by her unique combination of hopefulness, harmlessness, and heroism [that] functions to symbolically resolve public anxieties about the future’ (Reference Taft2020, p. 3). That is, girls are not only pressured to take on activist roles to solve problems not of their making, but media spectacles of girls as activists may also serve a function of resolving concerns about pressing issues for adults, who can be reassured that girl activist saviors are doing the necessary and inspiring work of ‘fixing the world’.

‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ seems to be actively framed in these terms, positioning children's activism as primarily about performance, spectacle and persuasion (‘voice’). Hope and heroism are both explicitly foregrounded, while ‘harmlessness’ – despite Bushell's angry and emphatic performance and statements – is reinforced through the logic of ‘training’, development and ultimate subordination to adult actors. Our point is not that Bushell and Roman Morello are not making a meaningful political intervention, but that (1) their intervention is framed as legible within the established public conceptualisation of children's activism, which emphasises voice over action, and (2) that genre – the norms and expectations of rock, and especially the mentoring and developmentally focused girls’ rock tradition – is particularly salient in structuring the type of intervention available to them.

In one prominent example demonstrating the appeal and relevance of the figure of the girl activist in public culture, even in the upper echelons of international politics, former US president Barack Obama posted about ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ on his Facebook page while attending the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26) in November 2021. Obama linked to the music video on YouTube and wrote that ‘[m]any social movements have been started and sustained by young people. Nandi and Roman used music as a way to share their compelling message about why we need to take action on climate change’.Footnote 12 Obama's Facebook post about Bushell's and Roman Morello's environmental activism and music video arguably both brought further attention to the song and affirmed children's potential political influence, while maintaining the distinction between adults’ direct agency and children's persuasive agency.

Collectively, the guest appearances in the video – as well as Obama's public display of appreciation – can be interpreted as endorsements of Bushell's and Roman Morello's activism and musicianship. On the one hand, this can be seen as increasing the legibility of their political and musical agency and counteracting common criticisms of children's culture as unimportant. On the other, the focus placed on these high-profile celebrity endorsements in much of the mainstream media coverage of ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’ (see BBC 2021; Krol Reference Krol2021) might perpetuate the idea that children – and girls especially – need to be granted admittance into credible cultural spheres, such as rock music, by (predominantly male) gatekeepers who hold a higher sociocultural status. These tensions shape Bushell's participation in and contributions to rock music, raising new questions about girls’ opportunities and status within this domain.

Final reflections: the social politics of girlhood in rock music

The interest shown Bushell by the international music press resonates with the ambiguities that have characterised past relationships between music journalists and female rock musicians, not to mention women's roles in rock culture more generally. As Norma Coates noted regarding women's increased impact on rock culture in the 1990s, the music press promoted ‘women in rock’ as the next big thing and capitalised on rock's changing gender dynamics while simultaneously contributing to containing change by Othering female artists: ‘“[w]omen” are only related to “rock” by being allowed “in”’ (Reference Coates and Whiteley1997, p. 61). One way in which women and girl performers are ‘allowed into’ rock culture is through the notion that men are seen as the architects of or otherwise somehow responsible for their success (Warwick Reference Warwick2007, p. 91), which effectively sidelines these performers in accounts of their own careers. A similar tendency is exemplified in some of the media coverage of ‘The Children Will Rise Up!’, as in the headline ‘See Tom Morello, Jack Black join kid drummer Nandi Bushell in video for new song’ (Enis Reference Enis2021), as well as in those parts of the media discourse surrounding Bushell that largely focus on male rock stars’ support of her (Day Reference Day2019; Doherty Reference Doherty2021; Reilly Reference Reilly2021). Furthermore, in June 2022, the opening paragraph of Bushell's Wikipedia entry described her as being ‘best known for her drumming skill, performing covers of popular rock songs which had drawn the attention of several musicians including Questlove, Lenny Kravitz, Dave Grohl, and Matt Bellamy’.Footnote 13 There is also a connection to be made between the visibility of Bushell's father in the media discourse surrounding her and Warwick's (Reference Warwick2007, p. 91) critique of the tendency to suspect women and girl performers of somehow owing their success to men (brothers, fathers, managers, producers).

Even if Bushell's success within rock music and outspoken support from prominent rock stars might indicate broadening opportunities for girl musicians within this domain, then, the social dynamics related to age, gender and genre still often operate in ways that limit girls’ cultural agency rather than bolster it. While rock music quite clearly represents a means for Bushell to assert her musical and political agency and disidentify with limiting stereotypes of girlhood, this process is complicated by enduring power structures and prejudices that disadvantage young girls. There is a tendency that the close association between Bushell and male celebrity musicians has become the most visible element in the media discourse surrounding her. This is problematic in relation to the long-standing cultural contempt for girls’ and womens’ supposed reliance on close relationships with male authorities in order to achieve success (Warwick Reference Warwick2007). In other words, the aspects of Bushell's musicianship and prodigy status that are consonant with dominant conceptions of girlhood as associated with dependency, domesticity and innocence take precedence in her media coverage, to the extent of risking to overshadow the activist and sociopolitical dimensions of her creative output and public persona.

It is an obvious point, but a seldom addressed one, that Bushell's rock star mentor-fans also stand to benefit from their relationships with her. The most evident example of this is the fact that the Foo Fighters’ ‘Everlong’ reentered Billboard's rock charts nearly twenty-five years after it was released, following the viral video of Bushell performing the song with the band at The Forum arena in 2021. Bushell played a key part in introducing the Foo Fighters’ music to a new generation of listeners. This arguably holds tremendous value during a time in which rock music is not nearly as culturally relevant as it used to be, which might indicate that the power dynamics between Bushell and her adult mentor-fans are not as straightforward as they appear at first glance. Surely, the success of the mentee affirms the mentor's position within a given field.

We also note that Bushell has made significant connections with and received considerable support from other women. Bushell has had online interactions with fellow musicians including Sheila E., Janet Jackson, Annie Lennox, Cindy Blackman Santana and Willow Smith. In a conversation on Instagram, composer Althea Talbot Howard praised Bushell's performance of one of her pieces for saxophone and suggested she might compose something specifically for her at some point in the future. Michelle Obama reposted one of Bushell's drum covers during Black History Month in 2020.Footnote 14 These interactions have received very little attention in the press, however. This suggests that rock discourse still primarily revolves around male performers, even when they fill the role of mentor, fan or industry broker.

The persisting association between rock music and (White) male performers emphasises the cultural significance of a Black girl's prominent success within this genre. As Maureen Mahon has demonstrated, Black girls and women are marginalised in the ‘standard rock histories preoccupied with the musical lineage and contributions of Rock's Great Men’ (Reference Mahon2020, p. 15). The tendency that Black girls’ and women's involvement in rock music is overlooked or otherwise diminished as a result of these dynamics (Mahon Reference Mahon2020, p. 2) is arguably illustrated by the extent to which established male rock stars take centre stage in the media coverage surrounding Bushell, but to simply point this out would risk undermining Bushell's achievements. As Mahon (Reference Mahon2020, p. 14) suggests, in order to counter the exclusionary effects of gendered and racialised genre boundaries we need to not only address the socio-historical and cultural contexts within which minority performers work but also the cultural impact of their work (see also Gorzelany-Mostak Reference Gorzelany-Mostak, Warwick and Adrian2016, p. 117).

The year 2022 saw Bushell perform at yet larger stages: she played at the Platinum Party at the Palace, a concert held outside of Buckingham Palace in celebration of the platinum jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II, and she joined Foo Fighters at Wembley Stadium to pay tribute to their drummer, Taylor Hawkins, who passed away unexpectedly in March 2022. In September, she released a new single and music video, ‘The Shadows’ (2022), which received widespread praise in the music press. Considering Bushell's achievements at the age of twelve, it seems reasonable to suggest that she has already contributed to making visible and garnering attention for Black girls’ contributions to rock music and culture. She has thereby counteracted the erasure of Black girls and women from rock history and extended the legacies of Black women in rock – Big Mama Thornton, Betty Davis, Tina Turner and others – into the contemporary cultural moment. She has done so while speaking up for the social and political causes that she views as important. The conspicuous support she has received from many well-established male rock stars is also significant, to the extent that it might actually represent a shift in the power structures within rock music that have distributed privilege unequally. Similarly, the performances and recordings Bushell engages in alongside established artists such as the Foo Fighters and Tom Morello amount to mixed-gender, multiracial, intergenerational and transatlantic collaborations that are explicitly framed as political, ethical and relational, pointing the way forward towards a more inclusive and diverse rock discourse.

These are not uncomplicated processes. And while we cannot hope to have dealt adequately with all the nuances and complexities related to girl musicians’ participation in rock music specifically and popular culture more broadly, we have aimed to demonstrate some of the ways in which the musical endeavours of children both are constrained by broader social and cultural conditions and contribute to shaping them. If ‘children's music’ is still often conceived of as a distinct and separate musical genre or form, cultural and media developments in recent decades make it increasingly clear that young musicians and audiences too participate in those broad fields of popular music and public culture – in all their complexity. Recognising the myriad opportunities for further research on these issues, we hope that our study of Bushell's early career prompts readers to reflect on the importance of addressing questions about identity, power and the social politics of genre in relation to children's musical endeavours.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Jacqueline Warwick for her generous feedback on an earlier version of this article.