Introduction

The United States is unique in terms of its permissive gun laws, high levels of gun ownership, and high levels of gun violence, especially when compared to other post-industrial societies (Mauser and Margolis, Reference Mauser and Margolis1992; Spitzer, Reference Spitzer2004; Goss, Reference Goss2006; Karp, Reference Karp2018; Yamane, Reference Yamane2023). Many observers find it confusing that a substantial minority of the American public so strongly opposes gun regulation in the face of increasing levels of gun violence, mass shootings, and the fact that gun restrictions keep the public safer (Smith, Reference Smith1980; Kleck, Reference Kleck1996; Utter and True, Reference Utter and True2000; Haider-Markel and Joslyn, Reference Haider-Markel and Joslyn2001; Newsome et al., Reference Newsome, Sen-Crowe, Autrey, Alfaro, Levy, Bilski, Ibrahim and Elkbuli2022). Regardless of America's extreme gun violence, or perhaps because of it, most gun owners feel strongly that their guns make them more secure and protected (Stroud, Reference Stroud2015; Dowd-Arrow et al., Reference Dowd-Arrow, Hill and Burdette2019; Sola, Reference Sola2021). In this paper, we contend that America's unique gun culture is not primarily based in utilitarian or security considerations but is a type of sacred worldview and identity. For many gun owners “…guns signify American core values of freedom, individual self-sufficiency, virtue, and citizenship” (Joslyn et al., Reference Joslyn, Haider-Markel, Baggs and Bilbo2017, 382). Our findings suggest that America's national passion for guns is a form of “magical thinking,” wherein the gun has taken on talisman-like powers to ward off evil and secure social respectability for a sub-set of Americans.

We utilize the sacred/profane framework initially proposed by Emile Durkheim to explain our findings. Specifically, the profane aspect of gun ownership is the belief that the gun provides a sense of protection and security. The sacred aspect of gun ownership is the belief that the gun provides a sense of moral goodness and social worth (see Spitzer, Reference Spitzer2004). As such, it becomes a potential weapon in a supernatural battle between good and evil (Vegter and Kelley, Reference Vegter and Kelley2020). We show that this sacred aspect of gun ownership is closely connected to faith in the power of prayer to provide health and wealth, support for the tenets of Christian Statism (see Li and Froese, Reference Li and Froese2023), and embracing conspiracy theories—a form of “Manichean” thinking (Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014). These beliefs all contain elements of “magical thinking” where individuals imagine causal relationships between unseen powers and the material world (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Hertzog, Kyritsis and Kerber2023). While magical thinking is often part of traditional religion, magical beliefs can be secular and are often at odds with modern theologies (Weber, Reference Weber1963; Durkheim, Reference Durkheim1995 [1912]; Stark, Reference Stark2001). And we find that a sacred attachment to guns is negatively related to church attendance but strongly predictive of quasi-religious forms of magical thinking. Dramatic declines in religious affiliations throughout the United States indicate growing levels of secularization (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Layman and Green2021), but the sacred aspect of gun culture alerts us that magical thinking may be more popular and influential than secularization trends suggest.

Inside gun culture 2.0

The concept of “gun culture” in the United States was first proposed by Hofstadter (Reference Hofstadter1970) to describe the unique role of guns in American society. Because guns have a distinct utility, gun culture is often defined by secular, practical, and individualistic needs (Celinska, Reference Celinska2007). Therefore, gun ownership is often used as a proxy for gun culture in many scholarly treatments of the concept (Felson and Pare, Reference Felson and Pare2010a, Reference Felson and Pare2010b). Recently, Yamane (Reference Yamane2016, Reference Yamane2017, Reference Yamane2023) observed that gun use in the United States has shifted dramatically from hunting and recreation to being mainly for self-defense purposes (see also Vegter and den Dulk, Reference Vegter and den Dulk2021). Yamane labeled this shift “Gun Culture 2.0” to indicate that the meaning and purpose of guns is now different from its historical origins. Specifically, guns have become largely synonymous with protection from crime, tyranny, and harmful others.

Mencken and Froese (Reference Mencken and Froese2019) contend that gun ownership itself is not enough to engender the emotional attachment to guns that many Americans feel (see also Joslyn et al., Reference Joslyn, Haider-Markel, Baggs and Bilbo2017). Qualitative research on gun culture tends to emphasize the nuanced symbolisms, norms, and rituals that avid gun owners share (Carter, Reference Carter1998; Kohn, Reference Kohn2004; Melzer, Reference Melzer2009; Taylor, Reference Taylor2009; Carlson, Reference Carlson2015a, Reference Carlson2015b; Stroud, Reference Stroud2015; Vegter and Kelley, Reference Vegter and Kelley2020). Joslyn et al. (Reference Joslyn, Haider-Markel, Baggs and Bilbo2017) observe a clash of gun cultures in which guns, for gun control advocates, represent power, inequality, and disregard for public safety, while pro-gun enthusiasts see guns as synonymous with freedom, individualism and virtue. In sum, gun-based group identities are more about “…what guns mean as opposed to what guns do” (Joslyn et al., Reference Joslyn, Haider-Markel, Baggs and Bilbo2017, 383).

To supplement qualitative and ethnographic studies of the symbolic and cultural meaning of guns, Mencken and Froese (Reference Mencken and Froese2019) created a series of survey questions to measure how gun owners feel about their guns. They found that owners who felt more emotionally attached to their guns, as measured by a “gun empowerment” scale, were more likely to oppose gun regulation and were more likely to condone violence against the federal government than owners who viewed their weaponry in merely utilitarian terms. Lacombe et al. (Reference Lacombe, Howat and Rothschild2019) find that a gun-related social identity is also significantly and negatively related to support for gun control legislation. Using national survey data, Warner and Ratcliff (Reference Warner and Ratcliff2021) also found that “political, social, and cultural anxieties” shape the meaning of guns more than “instrumental fears.” And Kelley (Reference Kelley2022) shows that women, while less likely to own guns, feel more empowered by weaponry than men. These studies highlight an important distinction between the utility of guns and their existential and emotional meaning. The deeper meaning of guns is explored in qualitative studies of gun culture. Many note how owners form strong collective identities around guns (Cash, Reference Cash1941; Carlson, Reference Carlson2015b; Stroud, Reference Stroud2015) and call attention to the ritual aspects of gun culture (Collins, Reference Collins2004; Taylor, Reference Taylor2009). In a Durkheimian sense, gun culture has religious elements, in that it produces strong group identities, rituals, and distinct sources of moral authority.

We extend the literature on gun culture further and analyze a more recent survey which contains previously used gun empowerment survey items. In preparing our data, we found that the established gun empowerment scale contains two distinct factors, which map onto existing observations about gun culture in America. The first is the concept of Gun Culture 2.0 which predicts that attachment will be based on the sense of security a weapon provides. The second is the moral and community elements of gun culture, which researchers have likened to a religion.

Our two major attitudinal dimensions of gun empowerment: (a) Gun Security: an index showing the extent to which gun ownership helps people to feel “safe,” “responsible,” and “confident”; and (b) Gun Sanctity: an index showing the extent to which gun ownership helps people to feel “patriotic,” “in control of my fate,” “more valuable to my family,” “more valuable to my community,” and “respected” (see Tables A1 and A2 factor analyses in the Appendix). While these factor groupings are data-driven, they map onto categories of sacred and profane. Conceptually, Gun Security is mainly a temporal, utilitarian, and individualist sentiment (profane), while Gun Sanctity is a moral, emotional, collectivist sentiment (sacred).

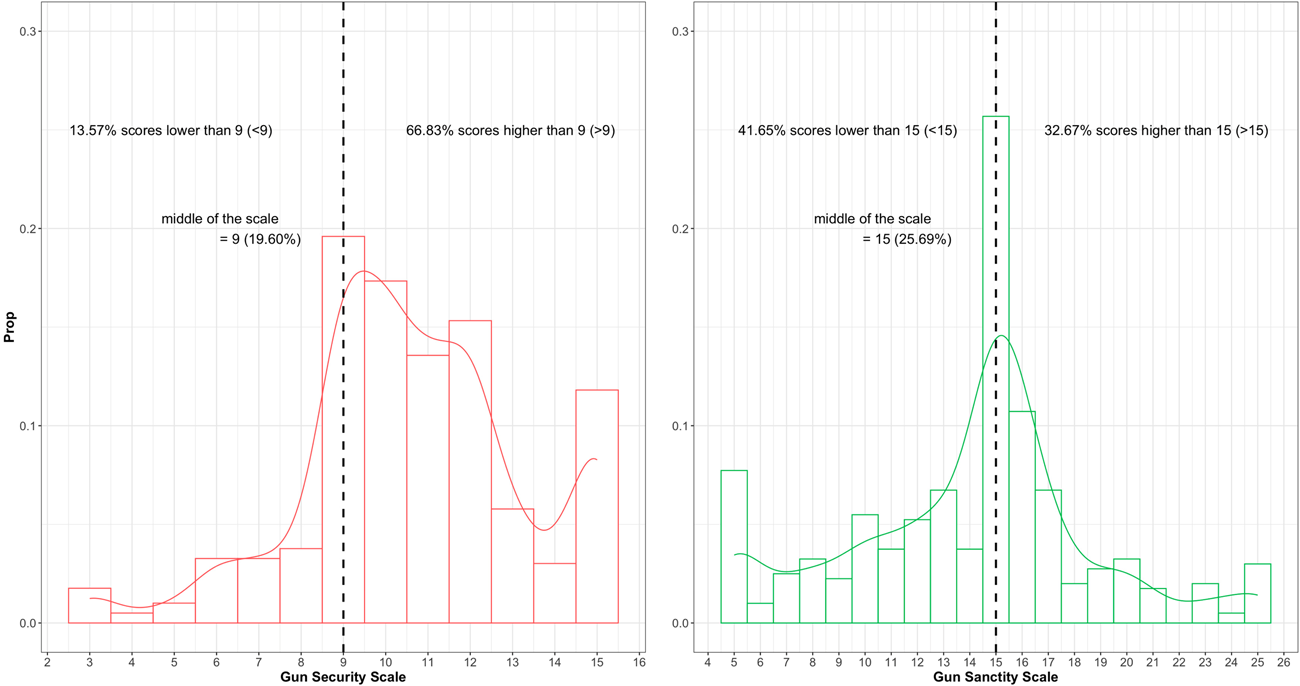

According to the item loading patterns, we construct a Gun Security index (Cronbach's α = 0.824) and a Gun Sanctity index (Cronbach's α = 0.908). We first observe raw score distributions of the two additive indexes. Figure 1 shows that two-thirds (66.83%) of our sample score higher than the middle point on the Gun Security scale and only a minority (13.57%) of gun owners score lower than the median score. This finding strongly confirms Yamane's Gun Culture 2.0 research which emphasizes the sense of security and protection that gun ownership brings. But another pattern emerges with our Gun Sanctity items. While the correlation between the two additive scales are high (Pearson's correlation coefficient is 0.66), fewer than one-third of gun owners (32.67%) feel strongly that their guns imbue them with moral value (those who score higher than the middle score on the Gun Sanctity scale); consequently, Gun Sanctity captures a distinct segment of gun owners to comprise the core of a sacralized gun culture. The following section will explore the conceptual differences and implications of these two measures of gun culture and how they relate to both religion and magic.

Figure 1. Distributions of Gun Security and Gun Sanctity raw scores among gun owners.

Gun Sanctity versus Gun Security

Durkheim's conceptual categories of “sacred” and “profane” are useful to the distinctions we are making. Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1995 [1912], 34) indicated that the sacred is the “distinctive trait of religious thought” which evokes a “combination of respect, desire, and terror.” Bellah (Reference Bellah2011, 1) described Durkheim's sacred as pertaining to “something set apart” from the material world; it presupposes the existence of a “non-ordinary reality.” The sacred, in this conceptualization, is a manifestation of the supernatural or metaphysical realm in our social reality; shared attachment to the sacred is experienced and evoked within objects, symbols, rituals, and social values that sacralize certain social facts and societal relations. And the sacred engenders social solidarity rooted in cultural homophily (Durkheim, Reference Durkheim1995 [1912]).

Unlike the sacred, the profane is incapable of producing a shared cultural identity and religiosity. Durkheim considered the profane a part of all common pragmatic activities. Smith (Reference Smith2020, 47) clarifies that the sacred and profane:

are not synonymous with “good and bad” or “good and evil”…. Rather, the sacred is contrasted by Durkheim with the mundane, the ordinary, the everyday, the utilitarian, the unremarkable, the practical, and the functional.

This clarification reminds us that the profane reflects a scientific or utilitarian view of the world as contrasted to the “non-ordinary reality” of the sacred. In turn, the Durkheimian dichotomy maps onto our measures of gun cultures: one (Gun Security) reflecting the utilitarian and material purpose of guns—to provide physical protection and security; the other (Gun Sanctity) reflecting the moral and metaphysical meaning of guns—to endow the owner with respect, goodness, and the sense of shared identity. Collins (Reference Collins2004, 37) explains that “whenever the group assembles and focuses its attention around an object that comes to embody their emotion, a new sacred object is born.” In this telling, the gun's sacred status was birthed to reflect and enhance the moral emotions of owners. And gun ownership is insufficient in itself to create social identity without some form of emotional attachment (Vegter and den Dulk, Reference Vegter and den Dulk2021, 811).

Mencken and Froese (Reference Mencken and Froese2019, 18) further note that individuals who derive moral meaning or “empowerment” from owning a gun are less devoted to traditional religious organizations. While evangelical Protestants have greater gun identity than do Mainline Protestants (Vegter and den Dulk, Reference Vegter and den Dulk2021), both high self-reported religiosity and frequent church attendance decreases the sense of gun empowerment (Mencken and Froese, Reference Mencken and Froese2019). This suggests that gun culture might act as a replacement for traditional or institutionalized religiosity. Rather than suggesting that it is merely a form of secular utilitarianism, we posit that gun culture has a religious sensibility, in a Durkheimian sense. But because the sacred aspects of gun culture tend to be distinct and even suppressed by church affiliation and attendance, we ponder the extent to which gun culture is more magically oriented than religiously defined. Reference DurkheimDurkheim (1995 [1912]), Weber (Reference Weber1963), and Stark (Reference Stark2001) all make the same distinction between religion and magic, while simultaneously recognizing that these two domains often overlap. Matthews et al. (Reference Matthews, Hertzog, Kyritsis and Kerber2023, 6) explain the general theoretical consensus that “magic functions as an instrumental manipulation of the sacred to obtain material ends, whereas religion focuses on non-instrumental interaction with the sacred through public rituals.” In this way, magic resembles science by offering mechanical causal hypotheses but differs from science by explicitly hypothesizing supernatural causal factors (Gosden, Reference Gosden2020). Because magical thinking combines material and supernatural causation it also tends to imbue the material objects with moral meaning; as Gosden (Reference Gosden2020: 33) notes in his extensive history of magic, “contemporary magic” combines “notions of how reality works in a physical sense with a strong moral dimension.”

In the case of gun culture, the concrete object of the gun provides the owner with feelings of moral goodness, social value, and control without reference to or need of the divine. Collins (Reference Collins2004, 101) describes Americans' fascination with firearms as a “gun cult,” arguing that “the long hours that gun cultists spend on reloading ammunition suggests that this is a ritualistic affirmation of their membership, something like a member of a religious cult engaging in private prayer, in actual physical contact with the sacred objects, like fingering the beads of a rosary.” The “cult” aspect of gun culture, in Collin's telling, makes it distinct from traditional religion, because even though it elicits a devotion to sacred belief, the power of the gun is not derived from God but rather the essence of the object itself. We, therefore, hypothesize that feelings of Gun Sanctity might be more closely related to “magical thinking” than traditional religiosity.

To test the extent to which magical thinking and traditional religiosity relate to Gun Sanctity, we look at beliefs about God's role in the world, the power of prayer, support for key tenets of Christian Statism, and acceptance of contemporary conspiracy theories. All of these beliefs indicate forms of both magical and religious thinking which assert supernatural causation or the agency of unseen forces to various degrees (see Vegter and Kelley, Reference Vegter and Kelley2020; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Hertzog, Kyritsis and Kerber2023). We predict that Gun Sanctity will be more closely related to all of these supernatural beliefs, but that gun ownership and Gun Security will not. In sum, we expect the sacred aspect of gun culture to predict magical thinking while the profane aspect of gun ownership does not. We explain the rationale for our expectations and how to distinguish magic from religion in turn.

Image of God

For most Americans, God is at the center of religiosity (Greeley, Reference Greeley1996; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow2015). The authority of God provides legitimacy and authenticity to the supernatural moral order (Berger and Luckmann, Reference Berger and Luckmann1966; Luhrmann, Reference Luhrmann2020). However, image of God research reveals great variation in how people think about God's role in this world. Using national survey data, Froese and Bader (Reference Froese and Bader2015) found that Americans who believe in God differ in terms of how “engaged” and “caring” God is in the world and how “judgmental” and “punitive” God is about human actions. Measures of God's engagement resemble indicators of “attachment to God” (see Liu and Froese, Reference Liu and Froese2020) and capture the extent to which believers think that God interacts concretely with the world. Froese and Uecker (Reference Froese and Uecker2022) also found that belief in a caring God is strongly related to church attendance and self-reported religiosity in the United States.

The role of God is also at the center of how theorists distinguish magic from religion. Stark and Finke (Reference Stark and Finke2000, 105) indicate that magic does not require “reference to a god or gods or to general explanations of existence.” Similarly, Weber (Reference Weber1963, 20) argued that the idea of “one god” subordinates and ultimately sub-plants magical processes and entities. Consequently, we expect that holding magical beliefs and valuing magical objects, while supernaturally oriented, would not necessarily be connected to belief in an engaged or caring God. And Upenieks et al. (Reference Upenieks, Hill and Robertson2022, 15) found no evidence that “a judgmental or engaged God were associated with a higher probability of gun ownership.” Few studies, however, have examined the role of images of God on gun culture.Footnote 1

In this study, we focus on belief in an engaged and caring God to determine the extent to which Gun Sanctity is tied to traditional theological faith.Footnote 2 We expect that belief in a caring God will not be associated with gun ownership or Gun Security (the profane aspect of gun culture), but could be aligned with Gun Sanctity. But if Gun Sanctity is a mainly a form of magical thinking, it would not necessarily be tied to a caring God. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H1a. Gun owners are not more likely than non-owners to believe in an engaged and caring God.

H1b. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of security (Gun Security) will be unrelated to belief in an engaged and caring God.

H1c. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of moral empowerment (Gun Sanctity) will be positively related to belief in an engaged and caring God.

The power of prayer

American believers attempt to communicate with God through prayer. While theorists argue that monotheism is a hallmark of traditional religion, prayer lies at the nexus of religion and magic. Weber (Reference Weber1963, 26) noted that “in prayer, the boundary between magical formula and supplication remains fluid” and that prayer has its “origin in magic.” Stark and Finke (Reference Stark and Finke2000, 106) similarly see a connection between magical activities and traditional prayer, noting that “magic does involve attempts to compel certain primitive spiritual entities to perform certain services.” The main distinction between magical practices and traditional prayer is that the latter tends to focus on non-worldly rewards. Stark and Finke (Reference Stark and Finke2000, 109) explain that “people do not always pray for something; often prayer is an experience of sharing and emotional exchange.” As such, modern prayer tends to be wholly religious when it is used for supplication, adoration, and solidarity. Prayer is more magical to the extent that it is thought to lead directly to concrete worldly benefits.

Americans pray for vastly different reasons (Froese and Jones, Reference Froese and Jones2021). Consequently, the practice of prayer captures a wide variety of assumptions about the ability of individuals to change the world through supernatural means (Stark, Reference Stark2001). Froese and Uecker (Reference Froese and Uecker2022) surveyed why and how Americans pray and established two prayer scales that measure variation in expected prayer outcomes. Specifically, they present the Prayer Efficacy Scale, which indicates the extent to which believers think that prayer is the “best way” to solve personal and world problems (Froese and Uecker, Reference Froese and Uecker2022, 12). They also identify the Prayer Support Scale, which indicates the extent to which believers ask God for health or financial support, two concrete worldly outcomes. Believing that prayer brings health and riches is more akin to magical thinking than other forms of prayer because it asserts a very concrete and testable outcome of prayer. Still, both prayer scales measure whether Americans believe in the power of prayer and are highly correlated with belief in an active God (Froese and Uecker, Reference Froese and Uecker2022, 17). Therefore, we hypothesize:

H2a. Gun owners are not more likely than non-owners to believe in the power of prayer.

H2b. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of security (Gun Security) will be unrelated to belief in the power of prayer.

H2c. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of moral empowerment (Gun Sanctity) will be positively related to belief in the power of prayer.

Christian Statism

Christian nationalism is a belief system that “celebrate[s] and privilege[s] the sacred history, liberty, and rightful rule of white conservatives” in the United States (Gorski and Perry, Reference Gorski and Perry2022, 14). The key word here is “sacred” because Christian nationalists tend to believe in a supernaturally ordered world in which “God favors the United States” (Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018; Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020). In fact, a popular scale used to measure Christian nationalism was initially proposed to indicate “sacralization ideology” or the belief that social and governmental institutions are and should be primarily influenced by religious concerns (see Froese and Mencken, Reference Froese and Mencken2009).

Recent studies indicate that the popular measure of Christian nationalism is not unidimensional (Davis, Reference Davis2022; Smith and Alder, Reference Smith and Adler2022). Li and Froese (Reference Li and Froese2023) found that there are two distinct dimensions of Christian nationalism; they are “religious traditionalism” and “Christian Statism.” They argue that Christian Statism captures a core sentiment of what popular literature describes as anti-democratic “Christian nationalism” or “white Christian nationalism,” while religious traditionalism captures a less political and more moderate sentiment.Footnote 3 In addition, Li (Reference Li2023) finds that Christian Statism shares a range of symbolism that conservative Protestants utilize to construct their sacred worldviews, such as the belief in an engaged God and biblical literalism, while religious traditionalism does not. We want to focus on “Christian Statism” because it better predicts whether Americans “embrace beliefs and symbols that intertwine American nationhood with Christian identity” (Li and Froese, Reference Li and Froese2023, 25).Footnote 4 While religiously oriented, Christian Statism is infused with a type of magical thinking in that it reflects the conviction that American successes are supernaturally determined. Thus, we expect that Americans who see politics and government as supernaturally guided will also be more likely to believe in the sacredness of guns. We hypothesize that:

H3a. Gun owners are not more likely than non-owners to hold Christian Statist beliefs.

H3b. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of security (Gun Security) will be unrelated to belief in Christian Statism.

H3c. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of moral empowerment (Gun Sanctity) will be positively related to belief in Christian Statism.

Right-wing conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories reject a “profane” sense of the world by asserting the role of unseen and unmeasurable forces in social outcomes and by ignoring empirical evidence that contradicts this assertion. In their expansive study of conspiratorialism, Oliver and Wood (Reference Oliver and Wood2014, 952) conclude that conspiracy belief is best predicted by “an attraction to Manichean thinking,” which holds that world history is guided by a metaphysical struggle between good and evil. Similarly, Robertson (Reference Robertson2015, 5) argues that “secular” conspiracy theories closely resemble sacred ideologies such as “theodicy, millenarianism, and esoteric claims to higher knowledge.” Matthews et al. (Reference Matthews, Hertzog, Kyritsis and Kerber2023, 9) explain that “many conspiracy beliefs share aspects of cognition in common with magic and religion.” In fact, clinical psychologists who study forms of cognition find that conspiratorialism and magical thinking are closely aligned (Eckblad and Chapman, Reference Eckblad and Chapman1983; Brotherton and French, Reference Brotherton and French2014; Bryden et al., Reference Bryden, Browne, Rockloff and Unsworth2018). The commonality involves the presence of belief in unseen causal forces without reference to the divine.

A 2012 survey shows that 63% of Americans believe in at least one major conspiracy theory (Uscinski and Parent, Reference Uscinski and Parent2014). Hicks et al. (Reference Hicks, Vitro, Johnson, Sherman, Heitzeg, Emily Durbin and Verona2023) found that Americans who bought guns during the COVID pandemic were more “politically and psychologically extreme” than gun buyers in general because they were more likely to believe in conspiracies. Lacombe et al. (Reference Lacombe, Simonson, Green and Druckman2022) find that first time gun purchasers during the COVID pandemic were more likely to have anti-establishment and conspiratorial beliefs than non-gun owners. The implications of these studies are that post-COVID gun communities have shifted to more extreme views, on average. Following these findings on right-wing conspiracies, we also look at: (1) the “Big Lie” or the belief that Trump won the 2020 presidential election, (2) the QAnon belief that the Democratic Party covertly runs a pedophile ring, (3) the view that the COVID vaccine is untrustworthy, and (4) the view that the dangers of COVID were exaggerated by the media. We picked these topics because there is substantial empirical evidence that each of these beliefs is false, yet a good portion of the public believes in them anyway. Because conspiratorial thinking promotes a sacralized worldview and tends to oppose profane/scientific explanations of current events, we also expect them to be related to Gun Sanctity. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H4a. Gun owners are not more likely than non-owners to hold conspiratorial beliefs.

H4b. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of security (Gun Security) will be unrelated to belief in conspiracies.

H4c. The extent to which gun owners feel a sense of moral empowerment (Gun Sanctity) will be positively related to belief in conspiracies.

Methods and data

We draw data from the Baylor Religion Survey wave 6 (2021) to test our hypotheses. The results of the 2021 wave are based on a mail and web survey conducted January 27–March 21, 2021, with a random sample of 1,248 adults aged 18 and older, living in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The Gallup Organization randomly selected individuals to participate using an address-based sample frame. Respondents had the opportunity to respond to the survey via the web or paper. Sixty-three percent of surveys were completed via paper and 37% were complete via web. Surveys were conducted in English and Spanish.

The survey was fielded using a self-administered instrument that was mailed to 11,000 randomly selected households. The final response rate, using the AAPOR1 calculation, was 11.3%. Complete cases that could be assigned a weight are included in the numerator of the response rate calculation. It is worth noting that the survey was fielded during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many areas experienced significant postal delays related to the pandemic. This likely had an impact on response rates, and Gallup did see a significant decline in response rates on other mail surveys fielded during the pandemic.

Sample weights were created to correct for unequal selection probability and non-response, and to match national demographics of age, education, gender, race, ethnicity, and census region. Weighting targets were based on the 2020 American Community Survey figures for the 18 and older population. The final sample compares favorably with distributions from the General Social Survey with regards to age, sex, education, marital status, political orientation, and church attendance.Footnote 5

Some questions are only asked for parts of the sample due to specific survey designs so that samples of analysis may vary for different hypothesis testing parts in this study. Besides the full sample (N = 1,248), we have three major sub-samples: (1) gun empowerment items were asked to gun owners only (N = 415); (2) the Images of God questions are asked to respondents who confirm their beliefs in God or higher powers/cosmic forces (N = 945); (3) the prayer questions were asked to those who confirm their practice of prayer (N = 939). Overlapping of sub-samples 1 and 2, and 1 and 3 creates another two sub-samples: (4) the God-believing gun owners (N = 333); and (5) the prayer-practicing gun owners (N = 326). Table A3 in the Appendix shows descriptive statistics in detail.

We use structural equation models to analyze the data and test our hypotheses. In our models, we treat Gun Security and Sanctity as latent factors because our analysis starts with factor analysis to test our scales' internal validity. For statistical estimation, we rely on Mplus Version 8.8 (Mac) given its strength in handling categorical data analysis as structural equation modeling (Muthen and Muthen, Reference Muthen and Muthen2012). For coding management, we use RStudio with R (4.3.1). To be specific, we use the “tidyverse” package (Wickham et al., Reference Wickham, Averick, Bryan, Chang, McGowan, François, Grolemund, Hayes, Henry, Hester and Kuhn2019) to clean data and run descriptive statistics and use “MplusAutomation” package to facilitate analyses in Mplus (Hallquist and Wiley, Reference Hallquist and Wiley2018). The missing data are estimated with either full information maximum-likelihood or pairwise deletion dependent on model estimators.

Findings

Preliminary analyses

We first conduct both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA and CFA) to examine if the gun empowerment items capture the two sentiments of gun culture. We use EFA for preliminary analysis to examine two main latent factors and use CFA to test if the two-factor model fits the data structure better than the one-factor model. Each item is measured with a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with “neither agree nor disagree” as the middle option. We treat these items as categorical (ordinal) endogenous indicators. Our EFA finding suggests there are two factors with substantially larger eigenvalues (eigenvalue for factor 1 is 5.345 and that for factor 2 is 0.927, see Table A1). Items asking if owning a gun makes respondents feel “safe,” “responsible,” and “confident” have loadings greater than 0.5 on factor 1 and items asking gun-owning feelings such as “patriotic,” “in control of fate,” “more valuable to family,” “more valuable to community,” and “respected” have loadings greater than 0.5 on factor 2. We construct and estimate a two-factor CFA model accordingly and compare model fitting statistics with the original one-factor model. This test shows that the two-factor models are statistically significantly better than the one-factor model (see chi-square results in Table A2). Taken together, our factor analysis findings support for the co-existence of Gun Security and Gun Sanctity as two independent—but correlated—gun culture sentiments/constructs as opposed to one Gun culture sentiment.

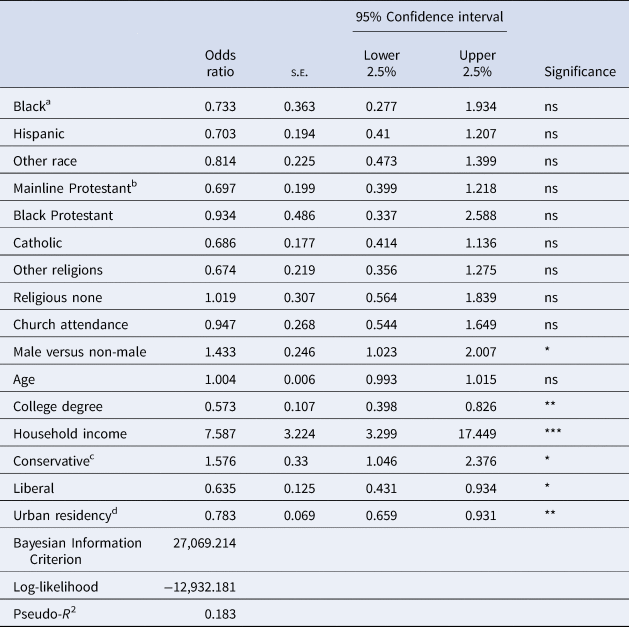

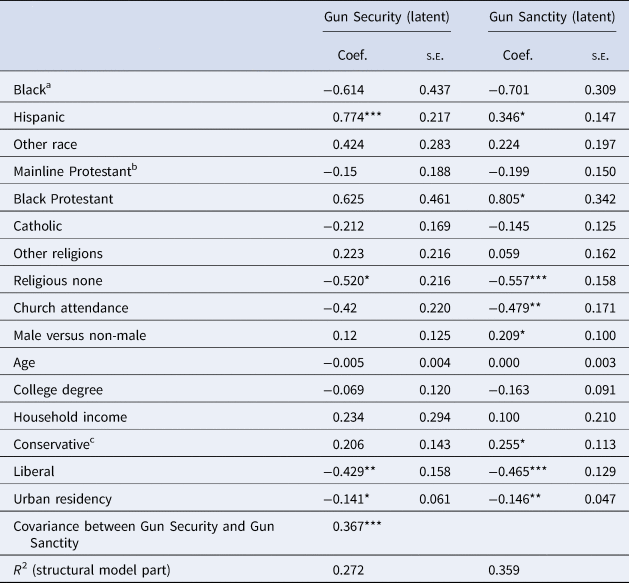

We also examine if Gun Security and Gun Sanctity capture different sub-populations among gun owners. If so, the two factors should be associated with different demographic factors. Our analysis includes a range of common demographic indicators such as religious traditions, church attendance, race, gender, age, education, household income, political ideology, and urban residency (see Table A3 for variable coding and recoding). We find that a respondent who is male or politically conservative has higher odds to own a gun while a respondent who has a college-degree, higher household income, or living in urban areas has higher odds to not own a gun (Table 1). Within the sample of gun owners (Table 2), we find that Hispanics, conservatives, and rural residents report higher Gun Security scores. Across religious traditions, only religious “nones” report Gun Security scores lower than white evangelicals.

Table 1. Logistic regression on gun ownership (full sample, N = 1,248)

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Maximum Likelihood with Robust Standard Error (MLR) with sample weight; full information maximum-likelihood is applied to handle missing data. We test the robustness of our finding by running a model with list-deletion sample and found little difference.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

d The urban residency variable is constructed as a four-point scale: 4 = large city, 3 = suburb of large city, 2 = small city, 1 = rural area.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 2. MIMIC model (measurement part) on Gun Security and Gun Sanctity scales (N = 370)

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Unweighted Least Square with Mean and Variance adjusted estimator (ULSMV) with sample weight as the gun culture measurement items are ordinal; pairwise deletion is applied to handle missing data.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We also find that men and political conservatives are more likely to feel enhanced morally and socially (Gun Sanctity) because of their gun ownership. This fits with Yamane et al. (Reference Yamane, DeDeyne and Méndez2021) finding that liberals and conservative gun owners share similar demographics but understand the gun differently. Contrasted to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics tend to score higher on both scales. This indicates that Hispanics are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to morally “identify” with guns. It is also very interesting to find that being a member of a Black Protestant church predicts higher Gun Sanctity score than (white) evangelical Protestants. Crucially, as Mencken and Froese (Reference Mencken and Froese2019) found, we show that church attendance is negatively associated with Gun Sanctity. This further suggests that Gun Sanctity is not a function of traditional religiosity or institutional religion.

Hypotheses testing

To further investigate the connection between gun culture and sacralization, we look at the extent to which (a) Gun Ownership, (b) Gun Security, and (c) Gun Sanctity predict belief in an engaged God, faith in the power of prayer, conspiratorial beliefs, and beliefs about the sacralization of the U.S. government (also known as Christian Statism).

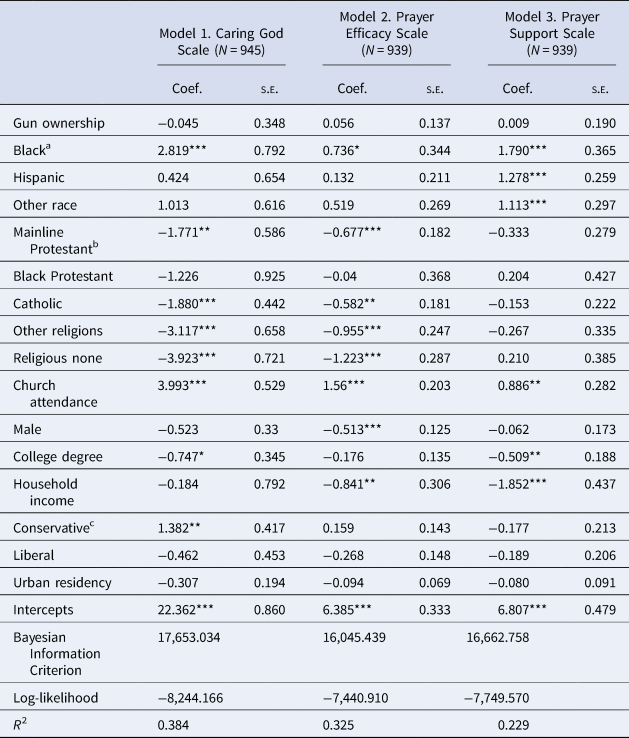

Image of God and the power of prayer

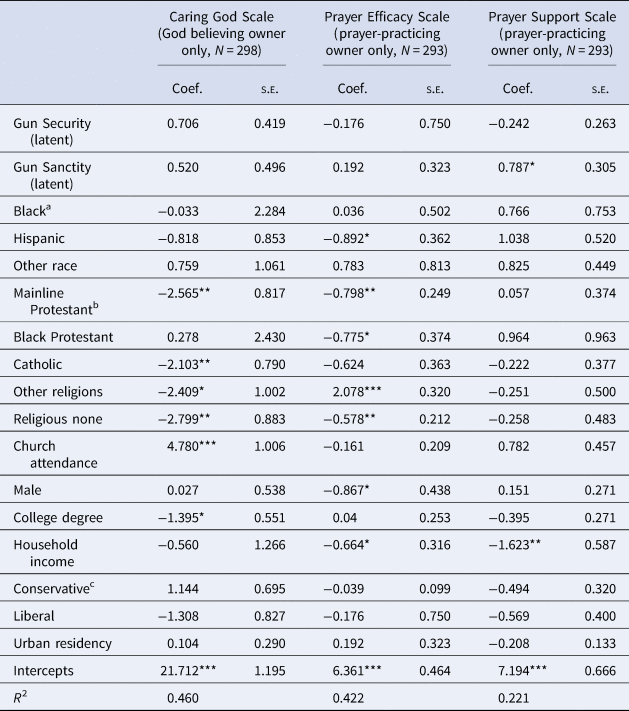

Hypotheses 1a–c and 2a–c examine if and how beliefs in an engaged and caring God and the power of prayer are related to gun ownership and the two gun sentiment indices. Table 3 presents the findings with gun ownership as the key predictor and Table 4 shows the findings with both Gun Security and Gun Sanctity considered. It is worth noting that we have four sub-samples to test our hypotheses because of the survey design: (1) that of respondents who do not deny the existence of God (the Caring God scale); (2) that of respondents who report prayer practices (Prayer Efficacy and Support scales); (3) God-believing gun owners; and (4) prayer-practicing gun owners.

Table 3. Gun ownership and religiosity

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Maximum Likelihood with Robust Standard Error (MLR) with sample weight as the dependent variable is continuous; full information maximum-likelihood is applied to handle missing data. We test the robustness of our finding by running a model with list-deletion sample and found little difference.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 4. Gun Security, Gun Sanctity, and religiosity

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Unweighted Least Square with Mean and Variance adjusted estimator (ULSMV) with sample weight as the gun culture items are ordinal; pairwise deletion is applied to handle missing data.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

First, analyses in Table 3 use sub-samples 1 and 2. Our findings support our hypotheses 1a and 2a. According to Table 3, we do not find any statistically significant associations between gun ownership and any of the mentioned beliefs.Footnote 6 It indicates that owning a gun is not related to higher religiosity among God believers nor prayer practitioners.

Analyses in Table 4 use sub-samples 3 and 4. Only half of our hypothesis 2c is supported. Within the samples of gun owners, higher Gun Security scores significantly predict higher scores on the Prayer Support scale. However, we do not find any significant associations between either Gun Security or Gun Sanctity and the Prayer Efficacy scale.Footnote 7 Interestingly, we find that Gun Security score is positively associated with higher Caring God score but negatively associated with higher Prayer Efficacy score nor Prayer Support score though all three associations are not statistically significant. In sum, our findings demonstrate that only Gun Sanctity is related to more magical beliefs about the power of prayer to produce tangible monetary and physical benefits than traditional religiosity.

Christian Statism

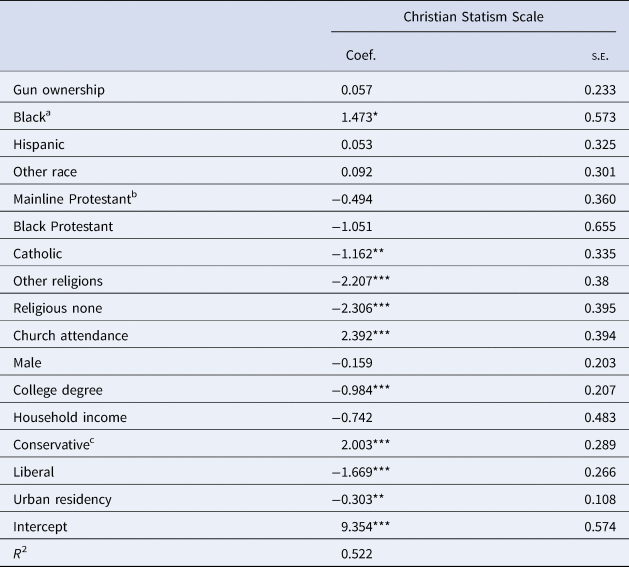

Tables 5 and 6 present results of testing hypotheses 3a–c. All three hypotheses are supported with our analysis. We construct two models to test associations between gun ownership and the two gun culture sentiments with the Christian Statism scale. Table 5 findings support hypothesis 3a that gun owners do not report higher Christian Statism scores than those respondents who do not own guns, accounting for control variables. Table 6 findings support hypotheses 3b and c. Within the sample of gun owners, Gun Security does not predict Christian Statism; but Gun Sanctity positively and significantly predict Christian Statism.

Table 5. Key Christian Statism on gun ownership (N = 1,248)

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Maximum Likelihood with Robust Standard Error (MLR) with sample weight and the link is Gaussian; full information maximum-likelihood is applied to handle missing data. We test the robustness of our finding by running a model with list-deletion sample and found little difference.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 6. Key Christian Statism on Gun Security and Sanctity scales (N = 369)

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Unweighted Least Square with Mean and Variance adjusted estimator (ULSMV) with sample weight and the link is Probit; pairwise deletion is applied to handle missing data.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

It is worth noting that across findings in Tables 5 and 6, church attendance positively and significantly predicts Christian Statist sentiments. We also notice that on the one hand, the association between being non-Hispanic Black (versus being non-Hispanic white) and Christian Statism is consistently positive across Tables 5 and 6 while the association between being Black Protestant (versus being white evangelical) and Christian Statism is negative. Certainly, this finding is consistent with Li and Froese's (Reference Li and Froese2023) observation that high devotion to traditional religious organizations and being non-Hispanic Black indicate strong desire to have a Christian nation-state. But, considering related associated patterns shown in Table 2, our findings may imply that self-worship of gun ownership (Gun Sanctity) and Christian Statism are complimentary ideologies for right-wing Americans who have different preferences and needs of religiosity.

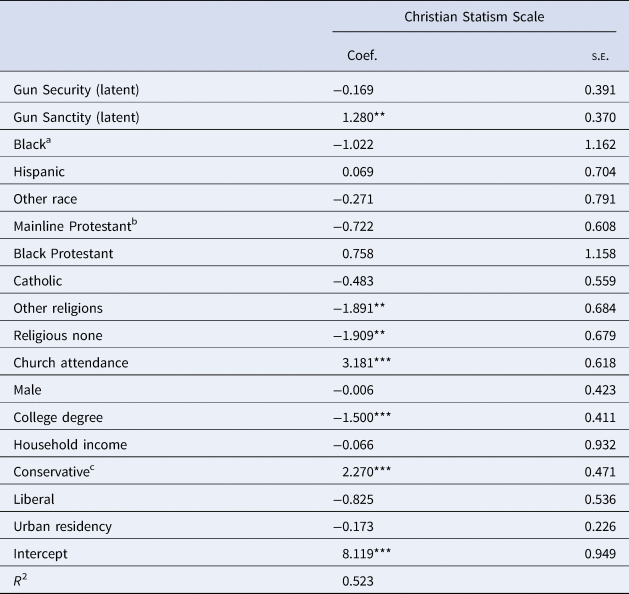

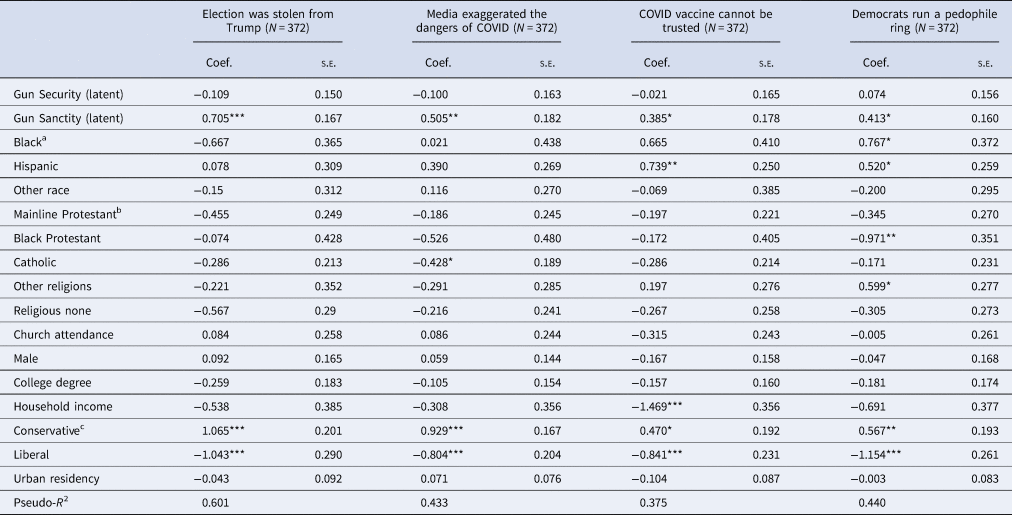

Conspiracy theories

Tables 7 and 8 present results for hypotheses 4a–c. We test the hypotheses using four key conspiracy theory ideologies in contemporary America. Each ideology is measured in a five-point Likert scale and treated as ordered categorical endogenous variables in the regression models. Findings in Table 7 partially support our hypothesis 4a that gun ownership does not indicate conspiratorial thinking. Still, owning a gun increases one's belief that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump and one's distrust of the COVID vaccination.

Table 7. Gun ownership and big lies associated with Trump (full sample)

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Unweighted Least Square with Mean and Variance adjusted estimator (ULSMV) with sample weight as the dependent variables are ordinal; pairwise deletion is applied to handle missing data.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 8. Gun Security, Sanctity, and conspiracy theories (gun owners sample only)

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Unweighted Least Square with Mean and Variance adjusted estimator (ULSMV) with sample weight as the dependent variables are ordinal; pairwise deletion is applied to handle missing data.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 8 shows the findings testing hypotheses 4b and c. Within the sample of gun owners, Gun Sanctity predicts all conspiratorial belief items. This supports the idea that an owner's moral attachment to their guns is predictive of magical thinking. In contrast, Gun Security is not tied to a magical or conspiratorial worldview. In fact, security is a wholly utilitarian reason to have a gun and does not require any moral or existential framework for legitimacy.

We also find interesting association patterns between the control variables and conspiracy theories. First, church attendance positively predicts the beliefs that the 2020 election was stolen and that the media exaggerated COVID but does not predict anti-vaccination and Democrats' pedophilia. This indicates that participation in traditional religious institutions is not always suppressive of magical thinking, as some theorists predict. Second, being Hispanic predicts higher anti-vaccination sentiments than being non-Hispanic white. This is consistent with research (see Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Batra and Batra2021) on COVID 19 vaccination skepticism among Hispanics and Blacks, which kinks this mistrust to the historical abuses of African Americans in medical research (e.g., Tuskegee). And last, conservative identity consistently increases the strength of beliefs in the conspiracy theories (also see Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Vitro, Johnson, Sherman, Heitzeg, Emily Durbin and Verona2023).

Discussion: gun culture and its threats

Sacralization

Secularization trends, such as declining religious affiliations and levels of church attendance, suggest that the public is becoming increasingly secular and scientific in its outlook and decision-making (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Layman and Green2021). Within this landscape, the popularity and ubiquity of guns can be attributed to rational utilitarian reasons, namely, the rationale that guns provide safety and security (Kelley, Reference Kelley2022; Yamane, Reference Yamane2023). Our data confirm that nearly all gun owners say that their weapons make them feel safer. This suggests that safety is the main goal of gun ownership and if it could be provided by some other means then guns would become less popular.

But Americans want guns for a variety of reasons and our findings show that a strong minority of owners feels that their weapons give them something more than security; guns provide them with moral standing, social status, and self-worth. Beyond the need for personal protection, these guns provide them with a sense of social identity (Vegter and den Dulk, Reference Vegter and den Dulk2021; Vegter and Kelley, Reference Vegter and Kelley2020; Lacombe et al., Reference Lacombe, Simonson, Green and Druckman2022). For these owners, the gun has become a fetishized object with magical properties that grant their users special characteristics. In short, the gun is sacred to them (see also Collins, Reference Collins2004; Vegter and Kelley, Reference Vegter and Kelley2020). This phenomenon is what makes discussions of gun regulation so complex. Utilitarian or profane discussions about the dangers of guns fail to address the magical attachment many owners have to them. As such, curbing gun violence through gun legislation will require a different approach.

While fewer Americans go to church, this has not led to a more scientifically oriented public, as some researchers purport. In fact, the American public is especially prone to believing in conspiracy theories. Nearly 20% of Americans, for instance, think that elite Democrats run a pedophile ring—the main tenet of the conspiracy group QAnon (Zihiri et al., Reference Zihiri, Lima, Han, Cha and Lee2022). And a growing number of Americans also think that the U.S. government's success is premised on its unique relationship with God (Li and Froese, Reference Li and Froese2023). The expanding popularity of conspiratorialism and Christian Statism stand in direct contrast to the supposed secularization of modern American society. The sacralization of gun ownership is another trend which fits this pattern, and other studies have identified a stronger connection among those who purchased guns during the pandemic (Lacombe et al., Reference Lacombe, Simonson, Green and Druckman2022; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Vitro, Johnson, Sherman, Heitzeg, Emily Durbin and Verona2023). We find that gun owners who feel deeply connected to their guns are very likely to believe in conspiracies and support Christian Statism.

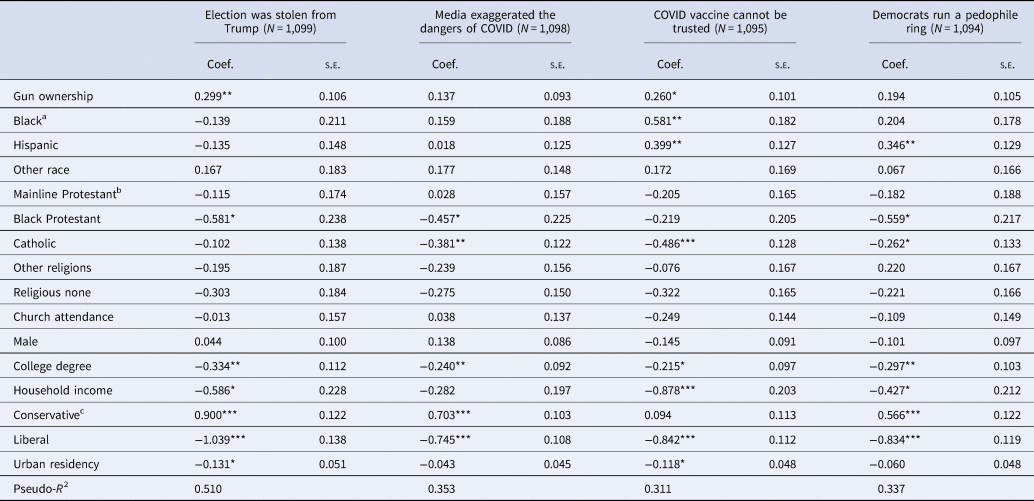

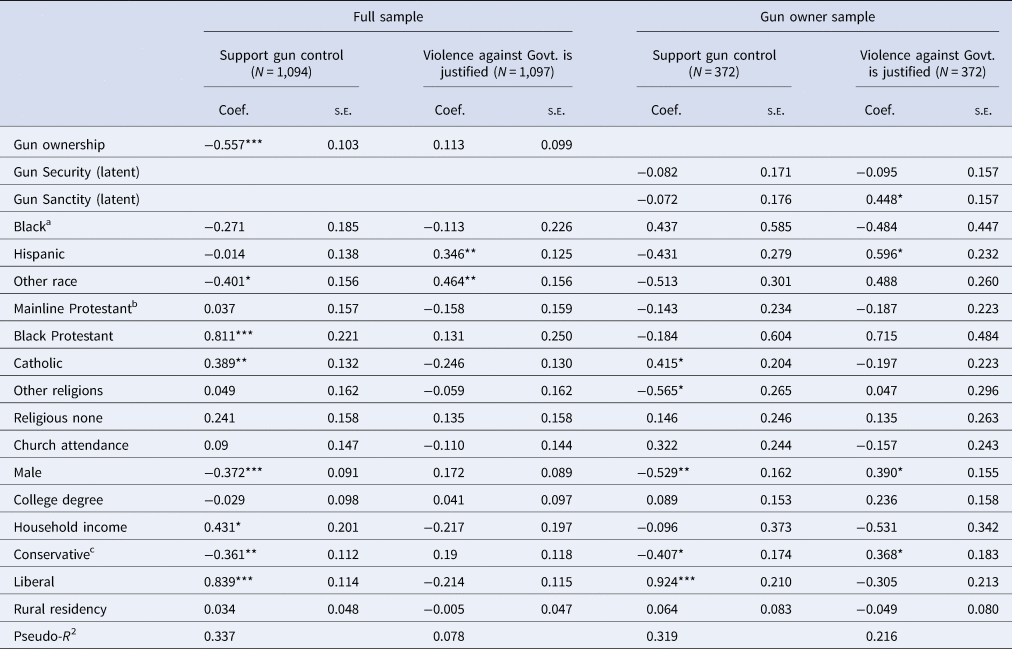

Once an object, concept, or belief has become sacred in the minds of believers its power lies beyond rational critique. Gun laws require rational unbiased judgments, but we fear that supernatural or magical concerns will permanently cloud them. These beliefs may even lead to violence. Mencken and Froese (Reference Mencken and Froese2019, 21) found that strong emotional attachment to guns “is significantly related to insurrectionism, or whether a gun owner believes that it is justifiable to take up arms against the government.” In replicating their analyses, we find that Gun Sanctity is also a robust predictor of insurrectionism (see Table 9).

Table 9. Gun control policy, anti-governmental violence, gun ownership, and gun cultures

Notes: All regressions in this table are conducted using Mplus 8.8 (Mac); estimator is Unweighted Least Square with Mean and Variance adjusted estimator (ULSMV) with sample weight as the dependent variables are ordinal; pairwise deletion is applied to handle missing data.

a Reference group is non-Hispanic white.

b Reference group is evangelical Protestant.

c Reference group is moderate.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

As Table 9 shows, gun ownership alone predicts opposition to gun control policies. But gun ownership is not related to justifying violence against the government. Similarly, we find that gun ownership alone does not predict Christian Statism or some conspiratorial beliefs. It is only a sub-set of owners, as distinguished by our Gun Sanctity scale, who exhibit these forms of magical thinking. And we also find that only Gun Sanctity is related to insurrectionism. These findings confirm that sacred beliefs can inspire strong, even violent, opposition to anything and anyone who questions them. For this reason, we should be critical and wary of how sacralized the gun has become.

Religion and magic

While gun culture has strong connections to conservative religiosity (Yamane, Reference Yamane2016), our findings indicate that gun owners who feel most attached to their weapons do not tend to go to church or believe strongly in a caring God (see also Mencken and Froese, Reference Mencken and Froese2019). Instead, we have shown that Gun Sanctity is more closely related to various forms of magical thinking. If gun culture is more akin to magic than religion, this has implications to how we think about addressing gun regulation. The distinction between magic and religion focuses on differences in the legitimacy and institutionalization of both practices. Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1995 [1912], 44) stated it plainly, “There is no Church of magic.” In other words, religion requires institutional authority and a theological framework while the authority of magic lies in the individual and requires no overarching schema or organization (Stark and Finke, Reference Stark and Finke2000, 106). If in fact magical, the gun's sacredness was not established by religious institutions or traditional theology, but rather is the product of individual superstitions and fantasies which have spread across a sub-population of gun owners.

Consequently, conservative Christians who make the case for gun regulation on scriptural or theological grounds will tend to have no sway over the magical thinking of gun owners. And it becomes unclear how the sacred status of guns can be mitigated if not through religion. Sacred objects cannot be critiqued rationally or for profane ends, and magical objects are not subject to religious authority. Thus, observed social outcomes and even traditional religious values become irrelevant to gun owners who are convinced of the gun's sacred status. While this does not describe the majority of gun owners, it does identify one of the reasons that any gun regulation is an anathema to those most deeply aligned with gun culture.

Limitations

There are limitations to our study. First, our samples are small due to specific survey designs which produce three major sub-samples. These limit the number of variables we can include in our analyses and the statistical significance of our findings. Second, we utilize cross-sectional data and cannot speak to the causality of any of the relationships we uncovered. Third, we have no direct measures of “magical thinking,” but rather use proxies like conspiracy theories, which have been shown to be related to magic (see Eckblad and Chapman, Reference Eckblad and Chapman1983; Brotherton and French, Reference Brotherton and French2014; Bryden et al., Reference Bryden, Browne, Rockloff and Unsworth2018; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Hertzog, Kyritsis and Kerber2023). Fourth, we do not have measures of whether or not gun owners affiliate with the National Rifle Association, a factor that is important for the development of gun identity in studies by Lacombe and colleagues (see Lacombe et al., Reference Lacombe, Howat and Rothschild2019). Future survey research into the sacredness of guns should employ larger samples, longitudinal data, and measures of magical thinking. Finally, magic and religion often overlap conceptually and so we cannot make clean distinctions between the two but rather suggest that some sacred beliefs and practices are more magical than others.

Conclusion

This paper is the one of the few studies that systematically investigates the religious and magical aspects of gun culture in the United States. Building on the Durkheimian paradigm of the sacred and the profane, we contend that the gun has become a sacred object for many gun owners. We find that most gun owners feel that their guns provide them with personal security, an expression of the profane or utilitarian need for guns (the Gun Security scale). Additionally, we identified a sub-group of gun owners who feel that their guns have sacred powers which instill them with moral goodness and social status (the Gun Sanctity scale).

Interestingly, we find that gun owners who score high on the Gun Sanctity scale were unlikely to attend church or believe strongly in a caring God. This suggests that the sacredness of the gun is not a function of traditional religion in the United States. Therefore, we tested the extent to which Gun Sanctity is predictive of quasi-religious beliefs derived from magical thinking rather than Christian theology or any established religious tradition. We found that Gun Sanctity, and not gun ownership nor Gun Security, was strongly predictive of conspiratorialism, belief in the power of prayer to grant health and wealth, and support for Christian Statism. These relationships suggest that Gun Sanctity is a form of magic thinking.

The Gun Sanctity scale also proves important because it helps predict when a gun owner feels that violence against the federal government can be legitimated. This finding replicates the discovery by Mencken and Froese (Reference Mencken and Froese2019) and raises fears that owners who worship their weapons are primed for violence against anything that would threaten their beliefs. Additionally, magical elements of gun culture make any rational or traditionally religious discussion of the utility or meaning of guns moot. As many classical and contemporary theorists assert, magical thinking is not influenced by empiricism nor religious authority.

In sum, the gun has become a sacred object for a sub-set of American gun owners. For them, the gun is a symbol that protects them in a supernatural war of good against evil. And they appear willing to use their sacred objects to defend these sacred beliefs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048324000312

Data

All data used in the article are from the Baylor Religion Survey (wave 6) which is publicly available from the Association of Data Archives (TheARDA).

Financial support

The Baylor Religion Survey is funded by Baylor University.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

Survey respondents have signed consent forms.

Paul Froese is a professor of sociology at Baylor University and the director of the Baylor Religion Surveys. He is the author of three books: The Plot to Kill God: Findings from the Soviet Experiment in Secularization (University of California Press), America's Four Gods: What we say about God and What that says about Us (Oxford University Press), and his most recent is On Purpose: How We Create the Meaning of Life (Oxford University Press).

Ruiqian Li is a senior researcher at the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL) at American University. His current research interests include Christian nationalism, public religion, and prevention of extremism and hate crimes.

F. Carson Mencken is a professor of sociology at Baylor University. He is a community sociologist who focuses on civil society, with emphasis on religion, culture, and civic engagement. His previous publications have appeared in such journals as Rural Sociology, The Sociological Quarterly, Social Problems, and Review of Regional Studies.