INTRODUCTION

Do the identity dimensions of a conflict shape whether individuals perceive local violence as caused by local or national factors? In ethnic conflicts with overlapping ethnic division (e.g., religion and tribe) such a relationship can have important consequences for how conflict is viewed, and the possible solutions needed. It is unclear how individuals in communities affected by ethnic violence perceive national and local contributors to conflict. Given that violence is mobilized by local actors and uses local narratives of injustice or group cleavages (e.g., Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006), communities may be more likely to blame local issues and actors. Conversely, communities might justifiably place the blame at the feet of national governments and actors (particularly in a federal system) that are seen as perpetuating local grievances or failing to prevent the exploitation of one group by another.

The “local versus national” question is further compounded when more than one ethnic dimension is salient in a conflict. Many African and South Asian cases exhibit overlapping ethno-tribalFootnote 1 and ethno-religious identities (Fox Reference Fox2000; Basedau et al. Reference Basedau, Strüver, Vüllers and Wegenast2011). Individuals' association of conflict with a particular ethnic dimension may lead them to different perceptions of the underlying local and national forces propelling that conflict. McCauley (Reference McCauley2017a) finds that policy preferences vary depending on how strongly individuals associate with their ethnic versus religious identity, and that a shift in a conflict's identity frame from ethnic (land-based) to religious (rule-based) logics can alter conflict mobilization and patterns. Vinson (Reference Vinson2020) finds that ethno-tribal and ethno-religious violence in northern Nigeria diverge in their pattern of conflict triggers and geographic spread and spillover. So too Gurses' (Reference Gurses2015; Reference Gurses2018) work on the Kurdish minority and conflict in Turkey emphasizes, for example, that individuals possess multiple identities (and distinctions within identity categories) that can differently shape attitudes and the politics of an issue or be distinctly mobilized. Hence, we expect the ideas, values, and interests individuals associate with their ethnic identities can diverge toward either local or national.

Yet, the scholarship on ethnic conflict has not closely considered how affected communities view the role of local versus national actors and issues, or whether and how ethnicity shapes conflict perceptions. Although a weak state facilitates instability and subnational violence, if individuals primarily perceive communal violence as rooted in local issues and actors, peacebuilding measures failing to address local dynamics are unlikely to promote peace. Conversely, if affected individuals primarily blame national-level issues and actors, local peacebuilding efforts will be stymied if there is no fundamental political action or change at the national level. As Basedau et al. (Reference Basedau, Strüver, Vüllers and Wegenast2011, 20) argue, more research into the “strong role of overlapping ethnic and religious identities, alone and in combination” is necessary, in particular the “in-depth investigation of the interaction of ethnicity and religion in conflicts and politics in general.”

This paper draws on data collected during a survey carried out in Jos, Nigeria during summer 2016. Since 2001, residents of the Jos area have experienced recurring bouts of ethnic violence that could be characterized by overlapping salient identities: ethno-tribal (indigenous versus non-indigenous) and ethno-religious (Muslim versus Christian). Further, local and national actors and issues could be blamed for recurring bouts of ethnic violence, as Nigeria is a federal system and the Jos area contains several local government areas, is the governing seat of Plateau state, and sits in an important area of overlapping religious and tribal interests in the center of Nigeria.

NATIONAL VERSUS LOCAL FACTORS IN ETHNIC CONFLICT

There is a clear divergence in the causal weight that scholars place on national versus local issues and actors in propelling subnational communal violence. National-level accounts emphasize the machinations of national or party elite in exacerbating identity cleavages. In such instrumentalist arguments, identity becomes a salient cleavage when national elites strategically manipulate local identities and communal violence for their own political ends, especially around elections (Gagnon Reference Gagnon1994; Brass Reference Brass1997; Posner Reference Posner2004; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2005; Eifert, Miguel, and Posner Reference Eifert, Miguel and Posner2010; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson and Chandra2012).

Scholars also emphasize communal violence as a product of state weakness, which is reflected in the absence of national policies to foster strong national identity, leading instead to politicization of ethnic identity and inequitable access to public goods (Miguel Reference Miguel2004). When local identities are closely aligned with those possessing national power, ethnic favoritism by the state may exacerbate subnational inter-group competition (Wimmer Reference Wimmer1997; Mayowa Reference Mayowa2001; Fjelde and Østby Reference Fjelde and Østby2014, 744–45). As violent cleavages emerge in response to these dynamics or during the uncertainty of national reforms or “critical junctures” (Bertrand Reference Bertrand2004), a weak state monopoly on violence allows tensions and violence to flare. As Elfversson (Reference Elfversson2015, 794) notes, “local communal conflict in Africa has to a large extent been analysed as a symptom of state weakness or failure, with the implication that conflict management is primarily an issue of building and strengthening state institutions….”

Other studies argue that local conditions render some communities more prone to ethnic violence, with grievances stemming from local economic inequalities, lack of access to services, political inequality and competition, and the nature of local institutions (Barron, Kaiser, and Pradhan Reference Barron, Kaiser and Pradhan2009; Fjelde and Østby Reference Fjelde and Østby2014; Pierskalla and Sacks Reference Pierskalla and Sacks2017; see also Tadjoeddin and Murshed Reference Tadjoeddin and Murshed2007; Stewart Reference Stewart2008). Indeed, Williams (Reference Williams2017, 35) notes an increase since the mid-2000s in non-state conflicts in Africa that “revolve around struggles to secure sources of livelihood, notably issues connected to water, land, and livestock.”

The motivation of local leaders and community members is important, as local actors may incentivize violence through patronage or fail to constrain it to achieve personal benefits (Brass Reference Brass1997; Berenschot Reference Berenschot2011; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson and Chandra2012, 369; Varshney Reference Varshney2014; see also discussion in Fjelde and Østby Reference Fjelde and Østby2014; Pierskalla and Sacks Reference Pierskalla and Sacks2017). Although unintended, decentralization policies or adoption of a federal system can also increase local or regional competition for power and incentives for political entrepreneurs to politicize ethnic cleavages (e.g., Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Roeder and Rothchild Reference Roeder and Rothchild2005; Brancati Reference Brancati2006; Erk and Anderson Reference Erk, Anderson, Erk and Anderson2010; Bakke Reference Bakke2015). Beyond political actors, Kalyvas (Reference Kalyvas2003) argues that “local cleavages” and “intracommunity dynamics” are central to understanding how violence occurs and who participates.

Other scholars emphasize the importance of local institutions (Tajima Reference Tajima2013; Bunte and Vinson Reference Bunte and Vinson2016; Vinson Reference Vinson2017; see also Eck Reference Eck2014; Lund Reference Lund2008) and networks in explaining why some communities are more prone to ethnic violence (Varshney Reference Varshney2002; MacLean Reference MacLean2004; Staniland Reference Staniland2012). Hence, even if larger state-level or structural factors are also salient to the conflict, local-level factors may be viewed as more salient to communal conflict.

The purpose of this discussion is not to set up a false dichotomy or to argue that ethnic communal violence must be understood as either the product of local or national factors, as the tapestry of communal violence is woven more often than not of both national- and local-level issues and motivations (see Krause Reference Krause2019). For this reason, Cordell and Wolff (Reference Cordell and Wolff2010, 8) argue that various levels of analysis should be considered in the study of ethnic conflict (see also Basu Reference Basu and Wilkinson2005; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson and Chandra2012, 371–72; Tajima Reference Tajima2013, 105). Rather, we argue that it is critically important to understand how individuals and groups affected by the violence perceive its causes and construct narratives. As Brass (Reference Brass1997, 5) argues, the very act of defining the nature and origins of ethnic conflict is a political act, part of the “construction of the interpretations” whether by media, politicians, or scholars. During Indian riots in 1984, Das (Reference Das and Wilkinson2005) notes the problems arising from the media and scholars mapping on interpretations or confusing narratives, with some accounts blaming the riots on local leaders and mobs, others condemning the state or party elite at the national level, and still others blaming some combination. However, an underexplored question is whether perceptions of responsibility might differ depending on the identity dimension individuals primarily ascribe to the violence.

HYPOTHESIZING ETHNICITY, CONFLICT LOCUS, AND SOLUTIONS

Tribe Local, Religion National

Why might individuals' perceptions of the local or national-rootedness of the violence be shaped by the identity dimension they most strongly associate with the violence? Recent scholarship highlights the distinctiveness of religious and tribal/ethnic identities in policy attitudes, patterns of conflict, and possibilities for negotiated settlement (e.g., Hassner Reference Hassner2003; Svensson Reference Svensson2007; Gurses Reference Gurses2015; McCauley Reference McCauley2017a; Reference McCauley2017b; Vinson Reference Vinson2020). We have reason to expect that communal conflicts viewed primarily as ethno-tribal are more likely to be associated with local conflict factors, while conflicts viewed as religious are more likely to be associated with broader national concerns. Since land-based disputes suggest grievances or competition over a specific territory, those who view conflict as rooted in ethno-tribal issues may see it as a locally-rooted problem compared to those rooted in religious “rule-based” disputes (McCauley Reference McCauley2017a). Further, as Lund and Boone (Reference Lund and Boone2013, 5) explain, jurisdiction of land in African states is embedded in “neatly nested systems of jurisdiction,” so local actors or customary law may have primary power in the adjudication of land disputes, and breakdowns in local jurisdiction could bear the brunt of the blame for conflict viewed as rooted in ethno-tribal cleavages.

Since religious disputes suggest difference rooted in competing worldviews that could be justified more broadly with a wider national (or international) community, those who interpret local conflict as religious may likely consider it a national problem transcending individuals and locality (e.g., Toft, Philpott, and Shah Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011, 21). Fox (Reference Fox2013, 126) argues religious identity is “central to how believers see themselves, their community, and the world.” Finally, since local religious leaders and organizations often fall under various organizational umbrellasFootnote 2 with prominent religious bodies advocating for their adherents, the participation of national religious institutions in the debate could influence individuals to associate religious conflict with a larger national dilemma.

Tribe National, Religion Local

Conversely, where disputes between ethno-tribal groups over land rights are viewed as the failures of national leaders or policy, such disputes may be perceived as rooted in larger national dynamics. Indeed, Boone (Reference Boone2007) highlights how issues of communal land rights and tenure represent larger constitutional and nationally politicized issues in many African states (see also Lund and Boone Reference Lund and Boone2013).

Also, given the prominence of local religious leaders across the global South (Vüllers Reference Vüllers2019), when these leaders participate in a narrative of religious othering, it may further a perception that local religious cleavages propel conflict. Isaacs (Reference Isaacs2017) argues that in communities where religious groups are internally fragmented, religious leaders have more incentive to adopt reactionary rhetoric in order to attract adherents, thus intensifying the association of local conflict with religious cleavages. That is, the conflict narrative may be internalized by a population as one about “these particular Christians or Muslims in our community” rather than an incompatibility between Christians and Muslims or religions across the country.

In short, although we cannot hypothesize with certainty the direction of the relationship, we have reason to expect there to be divergent local versus national associations in ethnic conflicts involving more than one overlapping and salient ethnic division. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1 Whether individuals perceive religious or tribal issues as more salient to inter-group ethnic violence will lead to divergent views of whether local or national factors are primarily to blame for the violence.

TESTING COMPETING PERSPECTIVES: THE JOS CASE

Jos, Nigeria is an ideal test case for examining whether individuals who associate the conflict with tribal or religious cleavages significantly differ in their perceptions of its local or national causes. As the capital of Plateau State in north-central or Middle Belt Nigeria, the city of Jos and surrounding area have been greatly affected by ethnic violence since 2001 (Best Reference Best2008; Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009; Higazi Reference Higazi2011; Krause Reference Krause2011; Kwaja Reference Kwaja2011; Human Rights Watch 2011b; Paden Reference Paden2012). Violence continues to haunt the area, with a recent set of attacks occurring in the summer of 2018 in areas just south of Jos (Inuwa Reference Inuwa2018). Furthermore, overlapping religious and tribal identities are salient to the conflict, with largely Christian indigenous groups (Berom, Afrizere, and Anaguta) pitted against Muslim non-indigenous Hausa-Fulani. These clashes consequently reshaped the ethnic geography of Jos, with the population segregating into largely Muslim Hausa-Fulani and Christian indigenous neighborhoods (Harnischfeger Reference Harnischfeger2004, 446). While the conflict is associated with long-standing disputes over the settler (or indigene) status of the Hausa-Fulani population and associated political rights, the violence also takes on a religious dimension, with clashes often sparked by religious offenses or seen as the product of religious competition and threat (Krause Reference Krause2011; Madueke Reference Madueke2018; Vinson Reference Vinson2020).

The Local Dimensions of Conflict

The nature of violence in Jos is local in a number of respects. First, the historical nature of the conflict draws on a divisive politics of indigeneity. While the predominantly Christian Afizere, Berom, and Anaguta are considered indigenous to the Jos area, the Hausa-Fulani Muslim population have long contested their non-indigenous or “settler” status and their lack of political representation and socio-economic rights. Debates about who originally founded Jos and who are the true “sons of the soil” persist, with the Hausa Muslim population arguing that they should be accorded indigenous recognition and rights since they have been settled in Jos for generations and contributed to its development since their migration to the area during the emergence of a tin mining industry under British colonial rule (Best Reference Bertrand2008; Adesoji and Alao Reference Adesoji and Alao2009, 155; Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009, 8; Kwaja Reference Kwaja2011; Orji Reference Orji2011, 475; Milligan Reference Milligan2013; Madueke Reference Madueke2018).

This issue became more divisive in 1991 when military leader General Ibrahim Babangida designated the new Jos North local government. Home to a Hausa-Fulani Muslim majority and constituting the central Jos metropolis, the indigenous population viewed this move as ceding political recognition and power to the non-indigenous (Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009; Osaretin and Akov Reference Osaretin and Akov2013). This event intensified political competition for control of Jos North's local government council with violence surrounding political appointments and local elections. Since control of the local government chairmanship entails authority to award indigenous certificates—which accords advantages in employment, land rights, education, and representation in government and civil service, to name a few—local government control is significantly contested (Harnischfeger Reference Harnischfeger2004, 445–46; Human Rights Watch 2006; Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009, 3; Higazi Reference Higazi2011; Krause Reference Krause2011; Madueke Reference Madueke2018, 92). Since the mid-2000s, local government elections in Jos North have been delayed a number of times due to likely instability. As Orji (Reference Orji2011, 476) contends, “at the heart of the Jos conflict is a ferocious struggle by different groups to control governance structures in Jos, and Plateau State in general.”

Second, the nature of Nigeria's federal system and resource allocation intensifies local competition. While the goal of the federal model is to funnel local interests through subnational government institutions, decentralization also entails significant allocation of national resources to states and local governments, rendering local politics more contentious (Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009, 3; Angerbrandt Reference Angerbrandt2015; Vinson Reference Vinson2017). Similarly, Milligan (Reference Milligan2013, 329) argues that the federal system “created a framework for the emergence of localized categories, a resource-rich executive office to be hoarded among exclusive networks, and an electoral forum through which groups competed for certification.”

Third, the role of local political actors and leaders also reflects the local dimensions of the violence. In past crises, a central grievance against Plateau state leaders is their failure to bring perpetrators to account and act on recommendations of multiple peace commissions (Osaretin and Akov Reference Osaretin and Akov2013, 350). Previous governors and political leaders of Plateau state are also accused of exacerbating identity cleavages for political ends and favoring indigenous groups (Kwaja and Kew Reference Kwaja and Kew2010; Krause Reference Krause2011; Orji Reference Orji2011, 477–78). Additionally, traditional and religious leaders fall on both sides of the peacebuilding or violence-instigating spectrum (Madueke Reference Madueke2018, 96), with some working for reconciliation while others use inflammatory rhetoric at public events, religious gatherings, or even “peace” meetings.

Finally, accounts of the Jos violence emphasize the way in which the violence takes on the tone of religious conflict (Human Rights Watch 2010; 2011a; 2011b; Krause Reference Krause2011; Vinson Reference Vinson2017). Apart from religious leaders in some cases exacerbating divisions, seemingly small religious offenses have sparked violent reprisals, and perpetrators have used religious litmus tests to identify victims (Human Rights Watch 2011b). Madueke (Reference Madueke2018, 452) argues that the “violence has always taken a religious tone. Individuals are maimed and killed, not because they are indigenes or Hausa, but because they are Christian or Muslim.”

The National Dimensions of Conflict

Despite the preceding case for the local rootedness of Jos violence, it is also possible to view the ethnic violence as a product of national political interventions, failures, or perceived favoritism. First, the emergence of communal violence in Jos can be traced to specific national government interventions in Jos politics and to the problematic articulation of indigeneity in Nigeria's Constitution. Indigenous Christian groups interpreted Gen. Babangida's decision to subdivide Jos North as the national government granting control of the central Jos metropolis to non-indigenous Hausa-Fulani Muslims (Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009, 9). The perceived “meddling” of subsequent regimes in local government politics has on occasion sparked violence. The first major clash between ethnic groups in Jos surrounded the political appointment of Alhaji Aminu Mato, a Hausa-Fulani, to head the Jos North Management Committee in 1994 (Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009, 11–12; Osaretin and Akov Reference Osaretin and Akov2013, 353). Furthermore, while the provisions related to indigeneity in the Nigerian Constitution are designed to enhance the “federal character” of Nigeria and represent its various ethnic communities in political institutions, it also reinforces the contentious politics of indigeneity at the local level, with individuals required to show sufficient evidence of indigeneity in order to obtain the benefits associated with indigenous status (Adesoji and Alao Reference Adesoji and Alao2009, 158; see also Human Rights Watch 2006; Adebanwi Reference Adebanwi2009; Ostien Reference Ostien, Chesworth and Kogelmann2009; Higazi Reference Higazi2011). Consequently, in Jos it is contested what “show evidence” means, and how far back one must go to establish the tie between ancestry and territory.

Second, the failure and contentiousness of the multiple peace commissions constituted in the aftermath of Jos violence may be viewed as a national issue. Following major violence in 2008 and 2010, Milligan (Reference Milligan2013) observes that contention between then president Yar'adua and two consecutive Jos governors tainted the commissions. Consequently, the actions of previous national leaders are interpreted as affirming the interests of local ethno-tribal or religious groups (Milligan Reference Milligan2013, 327–28). The inability of the federal government to work effectively with local actors and to make its findings public (i.e., to actually pursue perpetrators) exacerbates local ethnic tensions (Osaretin and Akov Reference Osaretin and Akov2013, 355; Milligan Reference Milligan2013).

Third, security forces deployed by the federal government during states of emergency are accused by locals of taking sides in the conflict and failing to provide effective security (Human Rights Watch 2009). In general, the weakness of the Nigerian state—lacking the capacity or will to provide effective security—could be blamed for the proliferation of ethnic violence throughout northern Nigeria (Osaretin and Akov Reference Osaretin and Akov2013, 356).

Finally, Jos is a microcosm of a larger religio-political struggle, because religious identity transcends local communal identities. As Krause (Reference Krause2011, para. 7) argues, “A thorough reframing of a once-localized conflict over indigene rights into a religious crisis of regional and national dimension has taken place.” A common refrain among Christians in Jos is that Plateau state is the last bastion preventing the nefarious forces of Islam from spreading to the majority Christian south. This broader sacralization of politics is a product of religious change in Nigeria since the 1970s with the political mobilization of influential Christian and Muslim religious bodies, particularly the emergence of a politically active Pentecostal-charismatic Christianity (Obadare Reference Obadare2018). Religious-political debates around various issues feed the perception that local conflicts that fall along religious fault lines are part of a larger religious and even cosmic struggle (Marshall Reference Marshall2009). For example, the “Sharia dispute” with the adoption of Sharia in criminal law by 12 northern states between 1999 and 2001 suggested an expanding religio-political contest and threat, and it sparked major violence across northern Nigeria (Harnischfeger Reference Harnischfeger2004; Laremont Reference Laremont2011). In the 2011 presidential election, violence ensued across northern Nigeria when Goodluck Jonathan, the Christian southern candidate, defeated Muhammadu Buhari, the Northern Muslim candidate (Lewis Reference Lewis2011; Human Rights Watch 2011a). Further, many incidents of communal violence spread from one local government or state to another as communities take revenge for the violence carried out against their co-religionists elsewhere (Vinson Reference Vinson2020). Hence, the Jos violence could be read as representative of a larger national debate, tapping into nationally salient narratives of injustice and political grievances. “Therefore, rather than containing conflict,” as Milligan (Reference Milligan2013, 328) argues, “intersecting group identities have interacted with national divisions to escalate conflict at both the national and local level.”

DATA

The data for our analysis is from a survey conducted in 2016 in Jos, Nigeria. To introduce randomization, QGIS (QGIS Development Team 2016) was used to layer grid cells over the Jos area. After a sample of grid cells were randomly selected, satellite images (Google 2016) of each cell were used to count and then randomly select structures within each cell, and research assistants were sent to each sampled structure where they then delivered a survey to a random occupant. The number of randomly sampled structures in each cell increased along with the number of structures in the cell to help account for variation in population density. After completing initial basic demographic questions aided by the research assistant, a tablet with an interactive survey software was used to collect answers to sensitive questions about conflict.Footnote 3 The survey was conducted with text and audio in both English and Hausa on the device to allow those unable to read to still participate. This resulted in a total of 1769 surveys in the usable final sample, after problematic cases were dropped.Footnote 4

Due to the cost and logistical challenges, the authors attempted to include a number of prompts and questions to explore various aspects of the conflict. For example, in a different article, the authors explore whether and how framing of conflict affects respondents' perceptions of the issues involved in the conflict and who is to blame (Vinson and Rudloff forthcoming). In order to answer these questions, experimental treatments (in the form of four invented news articles) were developed that varied the information about the possible groups responsible for a hypothetical conflict. Although this was necessary for the other project, it means that in this project we have to acknowledge the inclusion of these randomized treatments, as not every respondent received the same survey prompt. Therefore, we have been careful to include the randomized treatments in subsequent analysis to control for any related variation.Footnote 5

Several survey questions are used here to address the hypotheses. The first asks subjects to identify the cause of similar past conflict in Jos in terms of broad categories that include both ideational and non-ideational dimensions:

“Which of the following issues do you think is the biggest MAJOR CAUSE of the type of violence described in the article when it occurs in Jos? (Choose one)

• Economic issues

• Political issues

• Tribal issues

• Religious issues

• Other issues

• Not sure/Don't know”

The sample can thus be subdivided into those identifying the violence in the prompt as religious versus those who believe the violence is tribal. Research has indicated that not all members of conflict communities may view the ethnic dimensions of the conflict in the same manner (Varshney Reference Varshney2001, 365; McCauley Reference McCauley2017a), and research on Jos indicates this to hold true in this locality (Vinson and Rudloff Reference Vinson and Rudloffforthcoming). A follow-up question, which serves as the primary focus of our study, asked which level of government was most responsible for the conflict:Footnote 6

“Do you think the [appropriate issue here] that have caused violence in Jos are primarily a result of problems or policies at the: (Choose one)

• National or federal government level

• Plateau state government level

• Jos North local government area level

• Jos South local government area level

• Not sure/Don't know”

Furthermore, responses indicating the Plateau state government or local government are coded as “local,” since political issues and influence are interweaving between the two levels due to Jos being the capital and seat of the Plateau state government.Footnote 7

Finally, to test the implications for peacebuilding solutions, we rely on additional questions from the survey which asked: “Of the possible SOLUTIONS for ending this type of violent conflict in Jos, which solution do you think is the most important?”, with the potential answers to these questions matching the issue cause question above: political, economic, tribal, religious solutions as well as “other” and “not sure/don't know.” Respondents who did not answer “other” or “don't know” were asked a follow-up question about the appropriate level at which their chosen solution should be addressed: “Do you think the [PREVIOUS SOLUTION INDICATED] solution should be primarily implemented at the: National or Federal government level, Plateau State government level, Jos North local government area, Jos South local government area, not sure/don't know.”Footnote 8

Note that subsequent analysis focuses on tribal and religious issues and local versus national blame for conflict. Political and economic issue answers are not discussed in detail because (1) it is not the focus of the hypotheses, (2) the inclusion of economic and political responses were meant to give plausible “material” alternatives to possible identity responses (rather than a vague “other” response), and finally (3) there is little indication that blaming economic and political issues is strongly associated with blaming local and national government levels (see Table 5 in the paper appendix for an illustration).

ANALYSIS

Local versus National

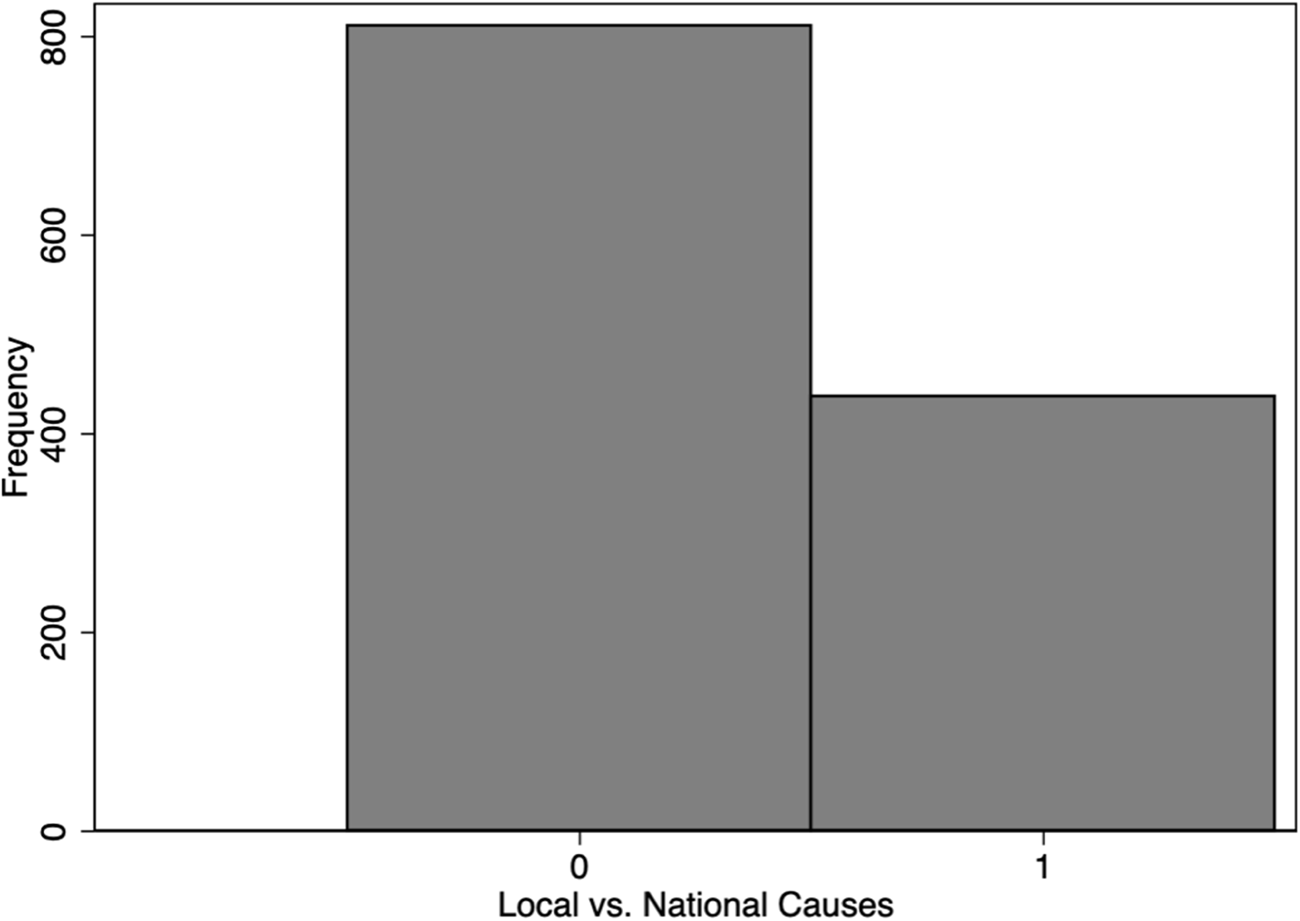

Figure 1 illustrates the difference between those who answered local and national factors were the cause of conflict, with individuals about twice as likely to note local factors, indicating that the contribution of local factors to the conflict are particularly salient for the population. Hypothesis 1, however, is about how perceptions of conflict issues are associated with blame for different federal levels. The overall breakdown of substantive responses in the survey is: 43% indicate religious issues, 27% political, 20% tribal, and 10% economic.Footnote 9 Over twice as many individuals indicated that religious issues were to blame compared with tribal issues, and over a third blamed political or economic causes, despite being prompted with treatments on the ethnic dimensions of conflict.

Figure 1. Histogram of responses to national versus local causes (0 = Plateau/state, Jos North, or Jos South causes, 1 = national/federal causes)

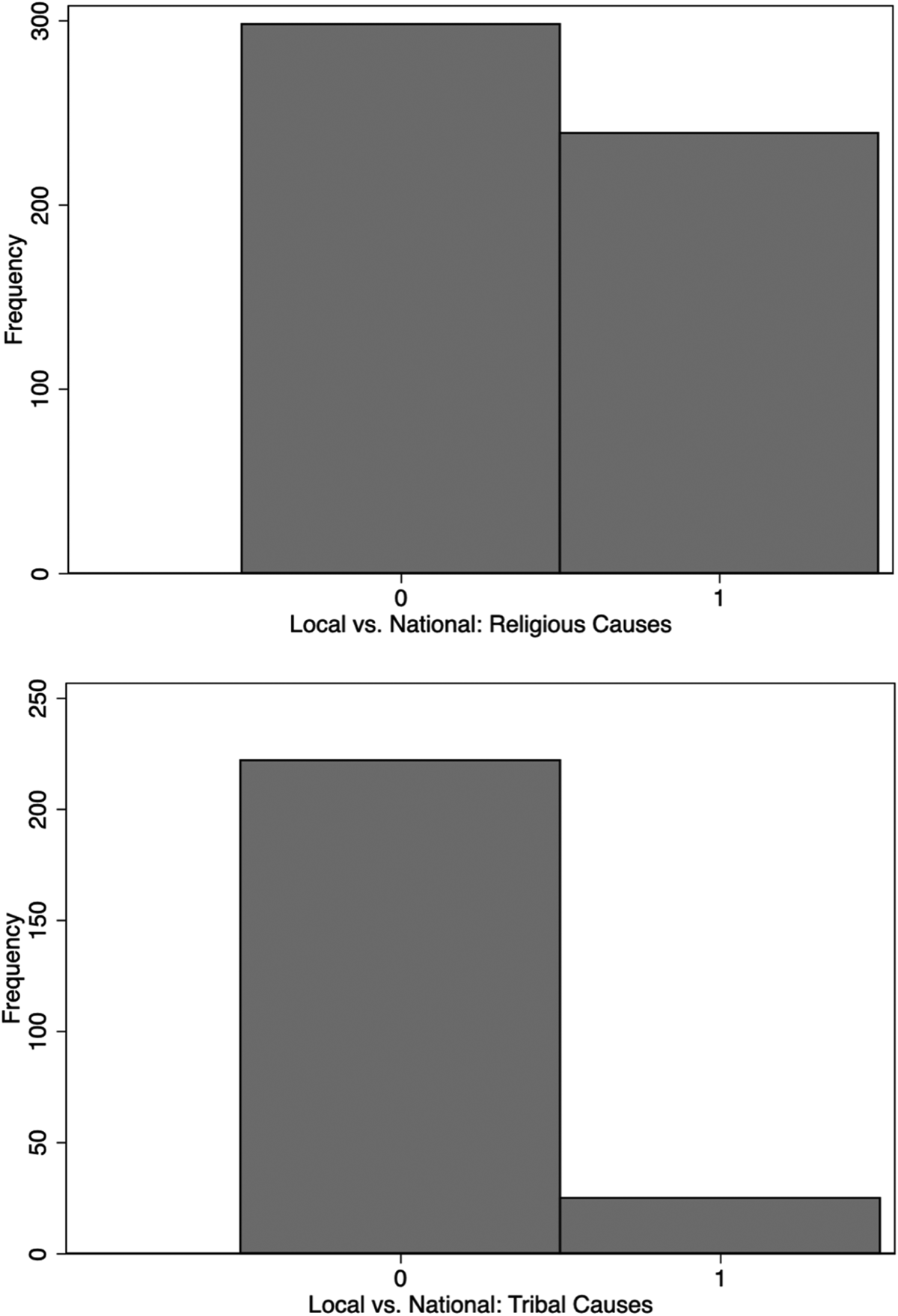

Those who responded that religious issues were at the heart of the conflict were relatively evenly split between blaming local versus national factors. Figure 2 indicates a greater proportion (approximately 55% compared to 65% in the overall sample) blame local issues rather than national issues. In comparison to those who indicated that Jos violence is primarily associated with tribal issues, the differences are stark. Figure 2 demonstrates that those who believe tribal issues are to blame are much more likely to blame local issues (approximately 90%) compared to national issues. This suggests a large divergence between those blaming religious and tribal causes, and how they view different federal levels of government, as expected in Hypothesis 1, with identification of religious issues associated with more likely blaming national-level factors compared with those that blame tribal issues.

Figure 2. Histograms of responses to national versus local causes if individual indicated religious causes (on top) or tribal causes (on bottom) (0 = Plateau/state, Jos North, or Jos South solution, 1 = national/federal solution)

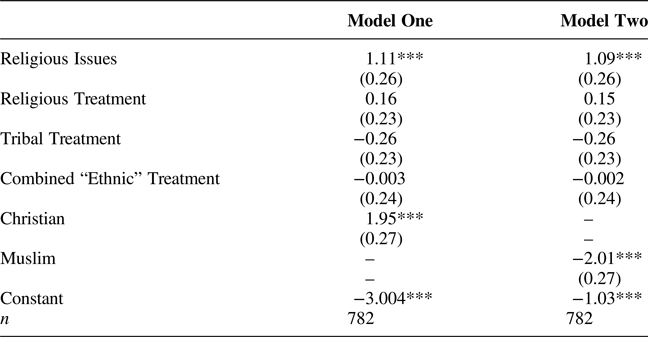

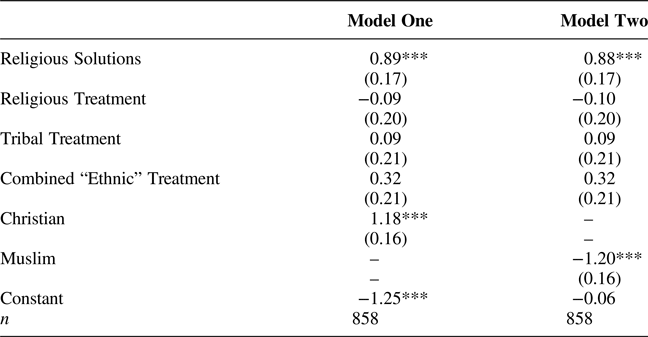

However, is it possible that other important factors may be driving this result? For example, given the importance of identity in Jos, is it possible differences between blame for national and local levels of government are associated with personal identity, rather than perceptions of the religious versus tribal character of the conflict? Table 1 summarizes a series of logistic regression analyses that confirm the differences between tribal and religious issues responses and blame for different government levels even with the inclusion of personal religious identity. For this analysis, only responses for those indicating tribal and religious issues as the cause are included.Footnote 10

Table 1. Analysis of how perceived cause of conflict (religious versus tribal issues) and religious identity are associated with blame for national and local government

DV: 1 if cause is national, 0 if local for tribal and religious cause responses.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Note that our interpretation of the religious issues variable in Table 1 does not change when we include Christian or Muslim identity, though it appears that personal Christian and Muslim identity is also associated with blame for local and national factors. Christians tend to blame national governments for conflict, whereas Muslims tend to blame local governments. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the importance of local recognition or “indigeneity” for the Hausa-Fulani Muslim population described above. It is important to note that we find that personal religious identity is also associated with whether one blames local or national factors, meaning there are strong associations between personal identity, perception of the causes of conflict, and the level of federal government typically blamed.Footnote 11

IMPORTANCE OF FINDINGS

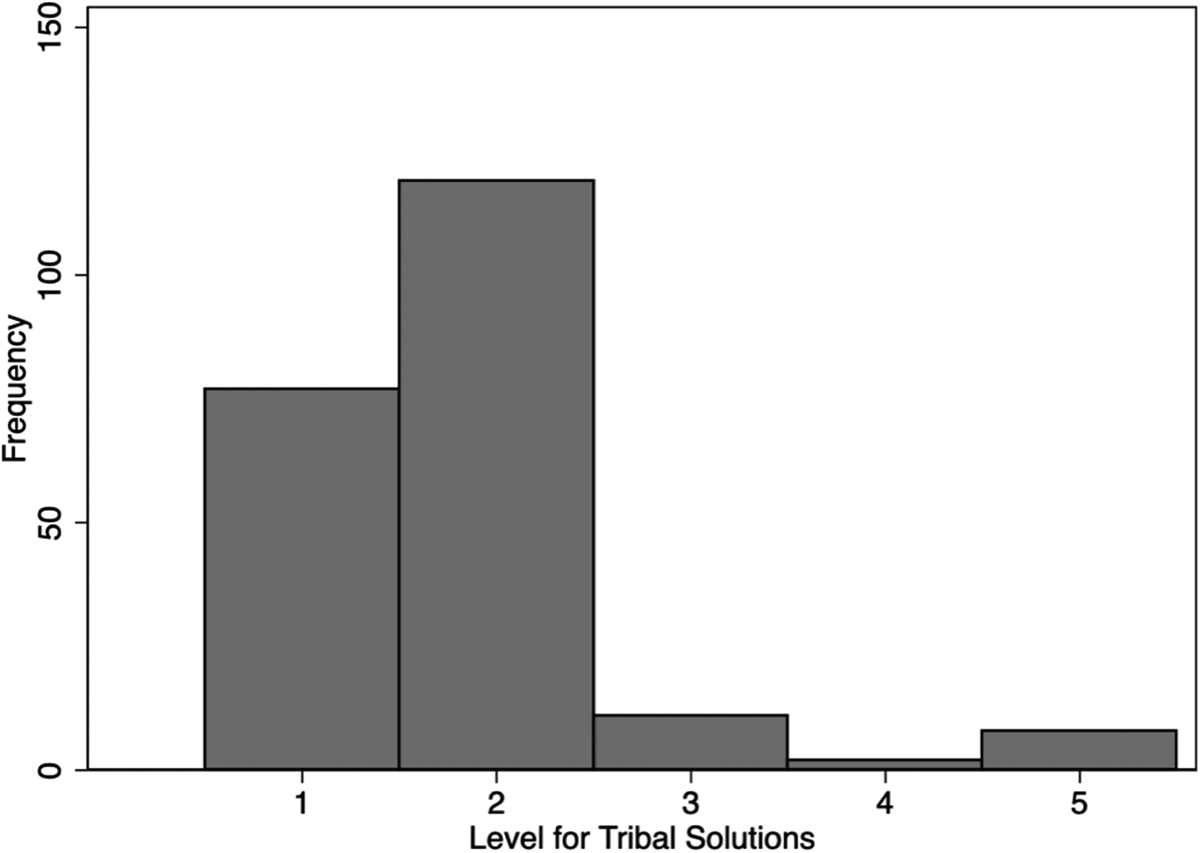

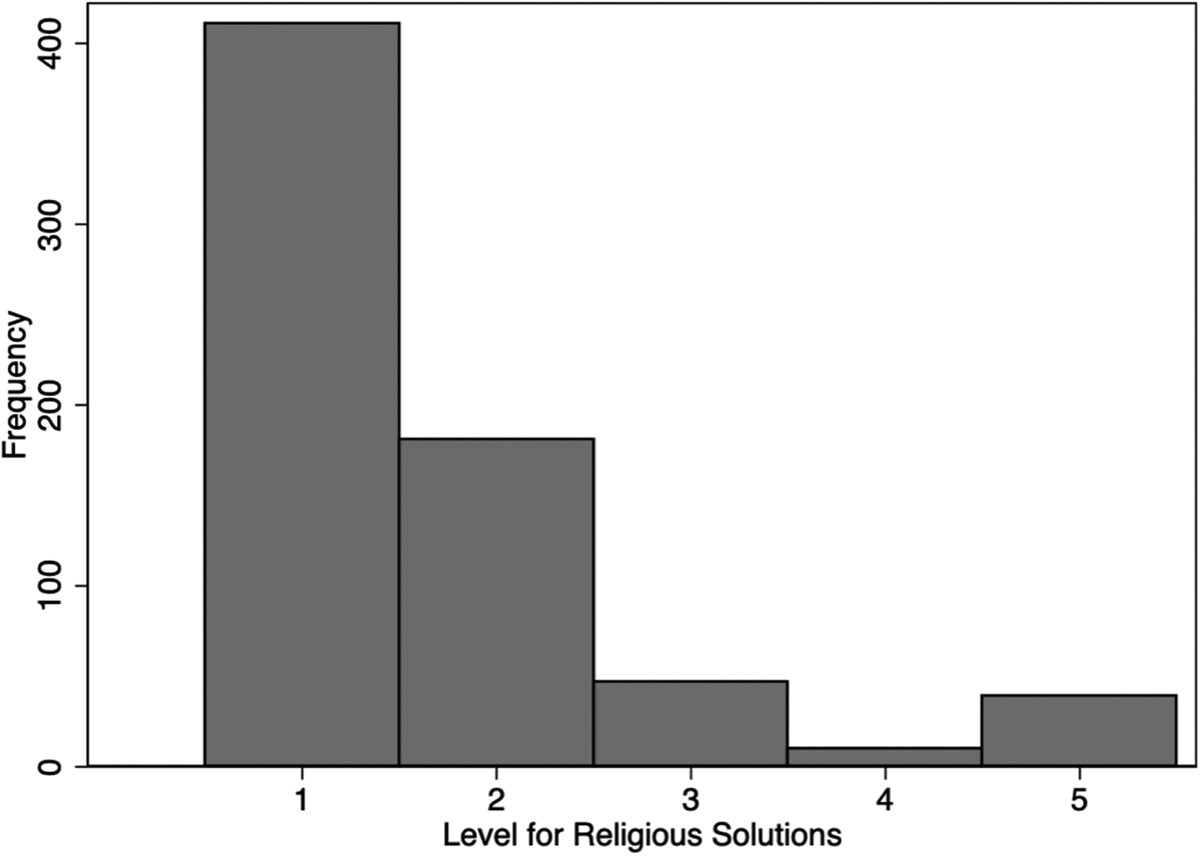

We believe the findings in this paper are important, not only for more fully exploring perceptions around communal conflict and the responsibility of different levels of government, but because these perceptions may have important implications for peace and in communities other than Jos. Peacebuilding efforts and programs are unlikely to be as effective if they do not take into account or speak to the views of those who are themselves affected by communal conflict—whether as victims or perpetrators (Canetti et al. Reference Canetti, Khatib, Rubin and Wayne2019). Kaufman (Reference Kaufman2006, 202) contends, for example, that peacebuilding efforts in the context of ethnic conflicts are problematic because peacebuilding actors view the endeavor through a rationalist lens of “interests and institutions,” rather than considering “the emotional and symbolic processes that influence how tangible issues are perceived and how they play out politically.” Figures 3 and 4 summarize the results of our follow-up tribal and religious solutions questions (detailed in the `Data' section), and illustrate how the importance of blame for different levels of government may extend to peacebuilding and solutions.Footnote 12

Figure 3. Histogram of responses to national versus local solutions if individual indicated tribal solutions (1 = national/federal solution, 2 = Plateau/state solution, 3 = Jos North solution, 4 = Jos South solution, 5 = not sure/don't know)

Figure 4. Histogram of responses to national versus local solutions if individual indicated religious solutions (1 = national/federal solution, 2 = Plateau/state solution, 3 = Jos North solution, 4 = Jos South solution, 5 = not sure/don't know)

Individuals who answered that the most important solution to the conflict is tribal are most likely to indicate that the appropriate government level for this conflict to be addressed is at the Plateau state government level (see Figure 3). There are relatively few individuals who believe the most important solution can come from either Jos North or Jos South local governments, while a significant minority believe that solutions at the national level are most important. In this case, it is unsurprising that individuals focus more on the Plateau state government level as the significant site for action, since Jos is the seat of the state government; decisions taken by the state government and governor strongly shape the contentious issue of the Jos North local government and inter-group relations. This mirrors results on causes. Just as those who feel the causes of conflict are tribal tend to blame policies at the local level, those who feel solutions should be tribal likewise look to the local level for these solutions.

Figure 4 summarizes the level of implementation results for those indicating religious solutions are the necessary remedy to the conflict. Such individuals are more likely to indicate national-level solutions as most appropriate. Unlike in the analysis of issue causes and levels of government (see Figure 2 earlier in the paper), where a slim majority of individuals indicate that the causes of religious violence are local, a strong majority believe that the national government is most important in solving religious conflicts.

These results emphasize the potential importance of peacebuilding efforts that are calibrated to how affected individuals view the conflict. Although a variety of peacebuilding efforts may be constructive, those focused on local measures may (or may not) match the expectations of local residents in regards to the ultimate causes of local violence or may not be viewed as appropriate when addressing particular dimensions of a conflict.

To further illuminate the relationship between the type of solution and the level of government looked to for the solution, we conduct analysis similar to that found earlier in the paper (see Table 1) with regard to issues/causes and levels of government. Table 2 summarizes these results. In this analysis, the dependent variable is coded 1 if an individual indicates a religious or tribal solution needed at the national level, and 0 if Plateau state government or local Jos LGA levels are indicated. Whether a respondent indicated religious or tribal solutions is the primary independent variable of this analysis. The results largely complement our earlier results for the causes of conflict (see Table 1): indicating religious solutions and Christian identity are associated with the view that national solutions are necessary, while indicating tribal solutions and Muslim identity are associated with the view that local solutions are necessary.Footnote 13

Table 2. Analysis of how perceived solutions to the conflict (religious or tribal solutions) and religious identity are associated with solutions at the national and local government level

DV: 1 if tribal or religious solution indicated as national, 0 if indicated as local.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

As is clear from section ‘Hypothesizing Ethnicity, Conflict Locus, and Solutions’ of the paper, there is important historical context unique to Jos, and these characteristics complicate simple attempts to generalize the findings to other cases. However, there are reasons why our findings may help us understand other, similar, communal conflicts. First, local conflicts with overlapping identity dimensions are common in many cases of ethnic conflict globally, as work on ethnic conflict in India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and other cases highlight (see broader discussion in Fox Reference Fox2000; Basedau et al. Reference Basedau, Strüver, Vüllers and Wegenast2011; Gubler and Selway Reference Gubler and Selway2012; Basedau, Pfeiffer, and Vüllers Reference Basedau, Pfeiffer and Vüllers2016). And local debate about the relative significance of these identities in shaping inter-group attitudes and responses is not uncommon (Kolås Reference Kolås2017). Grim and Finke (Reference Grim and Finke2007, 639) push back against work that minimizes the significance of religion relative to other ethnic identities and argue, “Ethnicity and religion frequently do overlap, just as land interests and religion overlap or as ethnicity and economic interests overlap; but they should not be conflated.” And in the broader literature, scholars find that tapping into particular identity narratives can re-shape inter-group perceptions and policy attitudes (e.g., Charnysh, Lucas, and Singh Reference Charnysh, Lucas and Singh2015; Gurses Reference Gurses2015; Reference Gurses2018; Robinson Reference Robinson2016; Kalin and Siddiqui Reference Kalin and Siddiqui2020). Hence, we have reason to expect that a distinct relationship between the perceived identity dimensions of communal violence and perceptions of government may hold true in other communal conflicts.

Second, while the particular historical evolutions may vary, both national and local factors are salient to conflict in other countries experiencing communal ethnic conflict. As Afrobarometer and Latinobarometer data emphasize, for countries across the global South, national and local religious leaders tend to be one of the most, if not the most, trusted actors compared to other types of leaders and institutions (Economist 2018; Howard Reference Howard2020), and the mobilization of religious actors and use of religious rhetoric in armed conflict settings is not unique to Nigeria (Toft, Philpott, and Shah Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011; Isaacs Reference Isaacs2016). Also, communal ethno-tribal or “sons of the soil” conflicts invoking historical claims to land and belonging are common in a number of countries in Africa and South Asia. Such conflicts draw on local historical grievances and land pressures as well as larger national political and institutional factors (e.g., Greiner Reference Greiner2013; Côté and Mitchell Reference Côté and Mitchell2015, 10–11; Klaus and Mitchell Reference Klaus and Mitchell2015; Boone Reference Boone2017). Our findings confirm from individual-level survey data a broader expectation or assumption in the ethnic/religious conflict scholarship that, given religion's ability to tap into broader moral or rule-based issues (Svensson Reference Svensson2007; Hassner Reference Hassner2009; Fox Reference Fox2013; McCauley Reference McCauley2017a), those who associate local ethnic violence with religious issues are more likely to see it as an issue that transcends locally-specific material grievances or conflict factors.

CONCLUSIONS

We explore how the perceived ethnic dimensions of violence (e.g., as tribal or religious) affect whether the violence is perceived as rooted in local or national factors. Through a survey conducted in Jos, Nigeria—a major city with significant communal violence that divides groups by overlapping ethno-tribal and ethno-religious identities—we show that perceptions of the level of governance responsible for local violence tend to be local in nature, however, beliefs about the causes of the conflict lead to significant divergence in these views. First, individuals who believe violence is inherently tribal, rather than religious, in nature are more likely to indicate local causes. Second, conflicts viewed as religious are more likely (compared to those viewed as tribal) to be associated with national causes. Furthermore, there may be important consequences when it comes to peacebuilding, as a majority of respondents in our survey indicated that the national level is most important in solving religious causes of violence, whereas respondents considered the Plateau state level of government as most important in solving tribal causes of violence. Scholarship on peacebuilding emphasizes the importance of local factors and actors in shaping inter-group conflict and determining the success of peacebuilding efforts (e.g., Saunders Reference Saunders1999, 39–48; Gawerc Reference Gawerc2006, 440, 448; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2003, 197), but, as these findings suggest, attention to how ethnicity, identity, and conflict interact will likely shape attitudes toward and the success of such peacebuilding efforts. Indeed, our analysis suggests that peacebuilding organizations or other government and grassroots initiatives must be attentive to how different groups perceive local violence and how the adopted peacebuilding activities present the peacebuilding issues. In the case of Jos, for example, a peacebuilding program targeting the Muslim Hausa-Fulani community and focusing on issues of religious misunderstanding may miss the mark if this community sees the impasse as primarily rooted in, for example, inequalities between ethno-tribal groups and the local government's failure to respond accordingly. So too, peacebuilding efforts involving members of the Christian indigenous community may struggle to gain traction if focused on local ethno-tribal inequalities and governance, since this group is more likely to see the conflict as rooted in broader national-level religious issues or divisions. Indeed, one takeaway for the Jos case (and other communities with overlapping identity-base conflict) is that peacebuilding initiatives may need to be intentional in recognizing the validity or reality of differences in conflict perceptions within a conflict community (as opposed to assuming the “real” dimensions of the conflict and designing programs accordingly). Building in dialogue to bridge different local perceptions of the conflict cleavages and/or meeting communities where they are at a program level may be most apt.

In sum, although further research is needed on the pattern across different country contexts, the main contribution of the study is the demonstration that conflicts with overlapping salient ethnic dimensions have significant and divergent implications for how individuals in conflict communities think about the government factors driving conflict and solutions. Aggregate large-n studies have found a relationship between overlapping ethnic identities and conflict or civil war onset, but we offer micro-level insight into the individual implications or effects on attitudes in communal conflict settings.Footnote 14 This paper demonstrates, therefore, the importance of a more nuanced approach to the study of ethnic conflict—the need to interrogate how perceptions of identity, conflict, and the locus of conflict interrelate. Scholars should be cautious, therefore, in applying the ethnic conflict label or assuming a rationalist-material lens is sufficient to understand such conflicts, given that ethnic conflict dimensions can be locally contested and this contestation can have important implications for conflict resolution or peacebuilding.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048320000590.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Katrina Korb and Danny McCain, professors at the University of Jos for providing vital logistical support as well as local knowledge for the sampling techniques. Additional thanks to Stephen Nemeth for help with the initial stages of the project. Thank you to the Department of Political Science, the Centre for Conflict Management and Peace Studies, and the Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Jos for their institutional support. The following research assistants did invaluable work on this project: Sanni Moses Peter, Abdullahi Yusuf, Abdullahi Salmanu, Abubakar Nabeel Abdulkareem, Bot Polycarp Moses, Bulus Jonathan Charles, Chidozie Diamond Anyalewech, Francis Emmanuel Tsaku, Fariatu Yahuza Ahmad, Ibrahim Musa Nuhu, Salihu Madinatu, Mafeng David Bot, Temitope Olamide Osoba, Omeka Matthew, and Ruqayya Sulaiman Nayaya.

Financial Support

This research was partially funded by the Peace Research Grant Program of the International Peace Research Association Foundation.

Data Transparency Statement

Replication data and files available from authors.