In the last two decades, the dynastic monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA)—have promoted the advancement of women in various ways and to varying degrees. However, even as they now employ many women in ministries and public services, obstacles to women exercising their rights and participating fully in the political, economic, and civic spheres remain (see, e.g., World Economic Forum Reference Forum2018). The countries’ state-led reforms have thus been criticized for consolidating inequality rather than aiming for and achieving equality between women and men (al-Mutawa Reference al-Mutawa2020; Pinto Reference Pinto2012, 105; Sabbagh Reference Sabbagh, Ballington and Karam2005, 57).

Considering the continued cleavage between progress and foot-dragging regarding women's rights, scholars have questioned why nondemocratic regimes adopt women's rights legislation (Donno and Kreft Reference Donno and Kreft2019; Tripp Reference Tripp2019). As Tripp (Reference Tripp2019, 4) points out, “The adoption of women's rights provisions in nondemocratic countries . . . challenges numerous assumptions developed with respect to Western countries about how and why women's rights are adopted.” Tripp (Reference Tripp2019, 64) argues that autocratic rulers do so for a variety of political purposes, including responding to popular pressure, keeping extremists at bay, or creating a positive international reputation and image of modernity and progress.

Focusing on the GCC states, this article contributes to this scholarly debate by investigating how the Gulf governments steer women's empowerment through the media to mobilize support and further their interests. Regulated by the state, both English and Arabic media outlets in GCC countries primarily serve to affirm and amplify the legitimacy of and public support for the state. However, in contrast with Arabic-language media, which largely addresses local populations, English-language media caters to both domestic and international audiences. These outlets provide a window into how GCC governments want to present themselves both internally and to the outside world. Women's rights thereby function as a central policy focus through which governments aim to stimulate modernization processes as well as bolster their reputation and legitimacy, both domestically and internationally (Al Obeidli Reference Al Obeidli2020, 1–2).

Examining the role of the English-language media in GCC states, this article undertakes a content analysis of newspaper headlines extracted from 15 English-language newspapers between 2008 and 2017 in the six countries. Applying a novel measurement strategy, our study explores how the media covers the topic of women's empowerment—that is, in what arenas of society (e.g., politics, economy, civil society, religion) and with what valence (positive, neutral, or negative) they report on women's empowerment topics. Moreover, we investigate whether news coverage concerning women's empowerment addresses news of domestic or foreign origin differently.

In doing so, our study contributes to two lines of growing research. First, it adds to research on women's rights and women's political inclusion in autocracies, particularly that which “moves beyond cultural and religious traditions as influences on women's rights” (Donno and Kreft Reference Donno and Kreft2019, 744). While Donno and Kreft (Reference Donno and Kreft2019) focus on party-based regimes, and Tripp (Reference Tripp2019) studies the Maghreb countries, our analysis focuses on the Arab Gulf dynastic monarchies. Second, this article contributes to the growing literature on the state-media nexus in nondemocracies. While scholarship on public spheres and media in autocracies is growing (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2020; Dukalskis Reference Dukalskis2017), it has yet to relate its insights to research conducted on public discourses about women and women/media interactions in nondemocracies (Al-Malki et al. Reference Al-Malki, Kaufer, Ishizaki and Dreher2012; George Reference George2020; Karolak and Guta Reference Karolak and Guta2020; Sakr Reference Sakr2008). Our analysis is a move in this direction, providing the first comprehensive study of English-language news coverage of women's empowerment in the GCC states.

We proceed as follows: Based on the scholarship on women's rights in autocracies, we first briefly review the political, social, and cultural background impacting on the opportunities and challenges to women's rights and empowerment in the GCC states. We then elaborate on the relationship between the media and the state around the GCC. On this basis, we formulate our research questions and empirical expectations and present our research strategy. Finally, we report and discuss the results of our empirical analysis, followed by concluding remarks.

In sum, our analysis shows that news coverage of women's empowerment is predominantly of positive valence across all countries and arenas of society and that coverage of foreign news is largely more polarized. We conclude that once nondemocracies focus more intently on women's rights, positive media portrayals, especially of domestic news, become a central tool to advance the legitimacy of and public support for women's empowerment and, by extension, the respective regime.

WOMEN'S EMPOWERMENT AND THE MEDIA: THE CASE OF THE GCC STATES

Women's empowerment refers to the establishment of equal rights, opportunities, and responsibilities for women and men across all domains of society (Alexander, Bolzendahl, and Jalalzai Reference Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2016, 433). A government committed to gender equality thus considers the interests, needs, and priorities of both women and men (Elson Reference Elson, Molyneux and Razavi2002). Numerous scholars have observed that there are significant gender disparities in Muslim-majority and Middle Eastern countries, in particular (Charrad Reference Charrad2001; Norris Reference Norris2009; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2003; Ross Reference Ross2008, Reference Ross2009).

Key scholarly perspectives on these disparities include (1) the “oil curse” thesis, which poses that there is a causal link between oil production, or the structure of the economy more generally, and the lack of gender equality (Ross Reference Ross2008, Reference Ross2009); (2) kinship systems that are based on tribal kin groups, hindering the development of greater gender equality (Charrad Reference Charrad2001); and (3) theses that emphasize the effect of culture and religion with autocracy as a central constraint to the advancement of women's rights (Norris Reference Norris2009; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2003). While these approaches explore the gap in gender equality, they hardly investigate the opposite—why autocracies support women's empowerment, what strategies they use, and what the consequences are for women and women's rights in such settings.

Recent scholarship has shed light on the nexus between nondemocracies and women's rights legislation (Donno and Kreft Reference Donno and Kreft2019; Tripp Reference Tripp2019). Focusing on the strategies of political leaders and the rationale behind their support for women's empowerment, Tripp (Reference Tripp2019, 262) argues regarding the Maghreb region that “[l]eaders . . . used women's rights internally to drive a wedge between themselves and Islamist extremists and externally to paint an image of their countries as modernizing.” Here, compliance with international treaties such as the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1979) is a central point of reference. And Donno and Kreft (Reference Donno and Kreft2019, 723) emphasize that “[i]nternational incentives for such measures are real: in a context of evolving global gender norms, advancing women's equality signals modernity and wins praise from the international community, which can translate to a variety of tangible and intangible benefits.” Bush and Zetterberg (Reference Bush and Zetterberg2021) recently confirmed the positive link between the advancement of women's rights and improvement in the international reputations of autocracies.

Donno and Kreft (Reference Donno and Kreft2019, 723) further argue that “[f]rom a domestic standpoint, making progress on women's rights is ‘safer’ than riskier types of electoral or civil society reforms, which can pose a direct threat to regime survival.” The promotion of women's rights allows for “pre-emptive coalition-building” since it often reconfirms and/or enlarges the regime's base of popular support (Donno and Kreft Reference Donno and Kreft2019, 722). However, while “[a]uthorities [might] use women's rights for their own purposes,” this does not mean that “women cannot benefit from these rights, even in limited ways” (Tripp Reference Tripp2019, 6). Donno and Kreft (Reference Donno and Kreft2019, 723) highlight that “de jure change represents an important milestone” in the advancement of women's rights in nondemocracies. Recent scholarship thus indicates that autocracies can have compelling interests in advancing women's rights and gender equality. While the political purposes might vary from one country to another, the topic of women's rights in the context of nation-building, modernization, and improving international reputation seem to be common markers in the study of nondemocracies and women's rights legislation.

Expanding the knowledge of women's empowerment in these contexts, this article focuses on the Gulf dynastic monarchies. While recent scholarship has mainly focused on autocrats’ political incentives and strategies, this study draws closer attention to how governments use the media, in this case, newspapers, to express their political preferences and mobilize support.

Women's Empowerment in the Arab Gulf Region

The dynastic monarchies of the Arab Gulf are rooted in male-dominated cultures and societies (Langlois and Johnston Reference Langlois and Audy Johnston2013, 993); the participation of women in the public sphere has thus been constrained by a combination of tribal patriarchy, conservative religious interpretations, and cultural stereotyping (Al Obeidli Reference Al Obeidli2020; Al-Rasheed Reference Al-Rasheed2013; Sabbagh Reference Sabbagh, Ballington and Karam2005, 55). Although Arab Gulf culture and religious beliefs are firmly embedded in the Qur'an and Islamic law, male domination is not the inevitable product of religious scripture, but of its culturally driven interpretations (Langlois and Johnston Reference Langlois and Audy Johnston2013, 994).

The GCC governments started promoting policies—often dubbed “state feminism”—for the advancement of women's role within society in the mid-1970s (Krause Reference Krause, Held and Ulrichsen2012; Pinto Reference Pinto2012). State feminism in the UAE, for example, differs from its counterparts in Western countries as female education and professional advancement are cast in terms of nation- and state-building processes (al-Mutawa Reference al-Mutawa2020; Pinto Reference Pinto2012).Footnote 1 While state-feminist contributions in the domains of health care, social welfare, and education are undisputed, scholars have criticized those efforts as serving state interests as they avoid issues such as female emancipation and the wide-ranging effects of patriarchy, especially in the context of kin and tribal solidarities (al-Mutawa Reference al-Mutawa2020; Al-Rasheed Reference Al-Rasheed2013; Prager Reference Prager2020; Zuhur Reference Zuhur2003). Maktabi (Reference Maktabi2016, 31) observes, for instance, that Kuwait and Qatar “equip women with certain resources and advantages—access to education and the labor market—but leave it up to the individual woman to cope with traditional views on women's position within the family and within society at large.”

With fluctuations in oil revenues, falling oil prices, and population growth have come increased pressures to diversify the economy especially since the turn of the twenty-first century. Consequently, GCC governments have aimed to reduce the region's extensive reliance on foreign labor in both the public and private sectors, creating opportunities for women's economic participation (Buttorff, Al Lawati, and Welborne Reference Buttorff, Lawati and Welborne2018, 68, 82). According to Sakr (Reference Sakr and Sakr2004, 2–3), one of the main drivers of the GCC countries’ signing of CEDAW in the early 2000s was that authorities “acknowledged that the oil boom was over and that . . . women salary-earners were an enviable asset to families”Footnote 2—even more so since Arab Gulf women have higher levels of enrollment in vocational training programs and at universities than men, with some of the highest female-to-male ratios in the world (Sakr Reference Sakr and Sakr2004, 70).Footnote 3

Emphasizing the international dimension of the shift, Davidson (Reference Davidson2013, 147) observes that many “non-oil economic sectors . . . rely increasingly on maintaining a sound international reputation.” The stronger focus on international audiences and approbation can also be observed in the launch of a variety of English-language newspapers in the first decade of the new century, including the Oman Tribune (2004), Qatar Tribune (2006), and Muscat Daily (2009) (all included in our analysis). The shift in GCC economies can, in sum, be viewed as a critical juncture for both women's empowerment and the governments’ increased concerns regarding international reputation and legitimacy.

Female suffrage was granted in Oman in 1994 and in Qatar in 1999, followed by Bahrain (2002), Kuwait (2005), the UAE (2006), and, finally, the KSA (2015).Footnote 4 While independent women's organizations (if any) are rare, there are state-led organizations such as the Supreme Council for Women in Bahrain (established 2002) that focus mainly on social, family, and health-related issues. An exception is the UAE Gender Balance Council, established 2015, which contributes to enhancing gender-equal legislation in society. In addition, women's rights have been expanded regarding personal status and family laws in Qatar (2005), the UAE (2006), and Bahrain (2009) (Maktabi Reference Maktabi2016, 21). In the UAE, for example, further changes were initiated from 2018 onward, including the introduction of salary equality and the proclamation of gender parity in the Federal National Council (UAE's national assembly) in 2019. To varying extents, these legislative shifts across the GCC states over the past decade were also influenced by the Arab Spring protests (2011–12). While “the outbursts of [the Arab Spring were] less spectacular and the voices more muted than elsewhere in the Arab world” (Seikaly and Mattar Reference Seikaly, Mattar, Seikaly and Mattar2014b, 238), they have nonetheless impacted the GCC states. For example, the KSA, Bahrain, and Oman were exposed to extended protests and demands for political reform and social change (Altorki Reference Altorki, Seikaly and Mattar2014, 92).

Despite these advances, much of the structure of gender discrimination remains intact (Metcalfe and Mutlaq Reference Metcalfe, Mutlaq, Metcalfe and Mimouni2011, 340), including unequal citizenship rights (e.g., women are often restricted from conferring their citizenship to spouses or children), the practice of guardianship, one-sided divorce and custody rights, and the legality of polygyny (Aldosari Reference Aldosari2016, 6; Al Gharaibeh Reference Al Gharaibeh2011, 100; Krause Reference Krause, Held and Ulrichsen2012, 93–94). In the business realm, the state oil companies of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, and Qatar allow for gender segregation, limiting women's career choices and opportunities (Al-Malki et al. Reference Al-Malki, Kaufer, Ishizaki and Dreher2012, 158; Metcalfe, Sultan, and Weir Reference Metcalfe, Sultan, Weir, Sultan, Weir and Karake-Shalhoub2011, 149). Additionally, in Bahrain, for example, women working in the private sector can legally be dismissed because of marriage, pregnancy, or taking maternity leave (Al Gharaibeh Reference Al Gharaibeh2011, 104).

State feminism proclaiming the liberation of women thus often also reinforces patriarchal structures on different levels in many of these states (Moghadam Reference Moghadam2018, 668; Sabbagh Reference Sabbagh, Ballington and Karam2005, 57). Nonetheless, “the adoption of women's rights reforms by leaders in a top-down fashion may bring about an awareness of a particular problem affecting women” (Tripp Reference Tripp2019, 280–81), contributing to a stronger focus on how women are treated or should be treated. This may in turn contribute to further policy reforms and social change. These political and societal dynamics are thus crucial to the study of women's rights legislation in autocracies.

Given the continued cleavage between progress and foot-dragging regarding women's empowerment in the GCC states, we were curious about how the governments use the media and the national press in particular to express their political preferences and further their state-feminist agendas, thereby engaging in “societal coalition-building” (Donno and Kreft Reference Donno and Kreft2019, 744).

The National Press in GCC States

Systematic scholarship on the role of the media in nondemocracies is still relatively recent (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2020; Dukalskis Reference Dukalskis2017) and has yet to relate its insights to research on women-media interactions in these regimes (Al-Malki et al. Reference Al-Malki, Kaufer, Ishizaki and Dreher2012; George Reference George2020; Karolak and Guta Reference Karolak and Guta2020; Sakr Reference Sakr2008).

All six GCC states embrace hereditary rule without any form of institutionalized opposition, and their governments strictly oversee the public spheres and media landscapes of their societies. In such a context, the discursive arena that constitutes the public sphere cannot be considered distinct from the state or the official economy (Habermas Reference Habermas and Burger1989). Rugh (Reference Rugh2004, 79) observes that “the primary requirement from the public and the press is absence of criticism and at least passive acceptance of whatever the regime does.” The accompanying media structure, which by law comprehensively regulates the actions of journalists and media outlets, leads to a “press that tends to support state policies rather than act as a watchdog” (Duffy Reference Duffy2014, 2). In her analysis of journalistic practices in the UAE, Al Obeidli (Reference Al Obeidli2020, 30) remarks that self-censorship by journalists and media outlets is practiced on a general basis, and that “[e]very media platform is used . . . as a propaganda tool to control the flow of news and guide public opinion in order to sustain political stability within [GCC] societies.” The state aims to establish the public sphere's foundations, delineate its boundaries, and monitor its content both regarding its inward-facing and outward-facing news coverage (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2020, 60; Dukalskis Reference Dukalskis2017, 4). Again, concerning women's empowerment in the UAE, Al Obeidli (Reference Al Obeidli2020, 2) observes that “[c]ensored and criticism free, all Emirati media platforms have been utilized to champion the government's ongoing agenda of empowering Emirati women, which it refers to as ‘nation building.’”

In international media freedom rankings, the GCC states thus fare quite poorly. According to the Freedom House index 2020, which defines media freedom as the “degree to which each country permits the free flow of news and information,” five of the six GCC states are “non-free” (Freedom House Reference House2020). Only Kuwait is rated “partly free”—in particular, the countries’ English-language newspapers, the Kuwait Times and Arab Times (both included in this analysis), appear to allow for relative diversity, competitiveness, and outspokenness (Maktabi Reference Maktabi2016, 25; Rugh Reference Rugh2004, 99, 101). Nevertheless, it is illegal in Kuwait to publish material that might affront the emir or other ruling families of the Gulf monarchies, or offend Islam, among others (al-Mughni and Tétreault Reference al-Mughni, Tétreault and Sakr2004, 124; Duffy Reference Duffy2014, 22).

To conclude, this top-down relationship between the government and the media is crucial—the media is supposed to further the government's views, thereby “presenting a positive and reassuring picture” (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2020, 63). If women's empowerment is imperative in the Gulf states, the media will publicize it accordingly.

Research Questions and Empirical Expectations

Based on the findings of the foregoing sections, and considering the salience of women's empowerment in the Gulf states over the past two decades, we develop a novel assessment method involving three central research questions and empirical expectations:

First, we ask, In which arenas of society (politics, economy, civil society, religion) has women's empowerment predominantly been addressed through the media? By questioning sectorial diversity, we aim to understand whether the discussion of women's empowerment is limited to a certain social domain or incorporates all arenas of society. Given the region's absolute monarchical institutions, we expect that women's empowerment topics will predominantly be discussed in the realm of politics and that sectorial diversity is low.

Second, we ask, With what valence (positive, neutral, or negative) does the GCC countries’ national press report the topic of women's empowerment? Given the top-down state-media relationship, we expect that discussion of women's empowerment will not involve a strongly polarized valence but clearly support the government's direction (i.e., positive reporting).

Third, we explore, To what extent are there differences in the reporting of domestic and foreign news on women's empowerment? Given the top-down approach of addressing women's empowerment and focus on public support, we expect that news on domestic reforms will predominantly be of positive valence. Furthermore, we expect that news stories of foreign origin, if covered, are most likely reported with a stronger polarization, given their greater distance from governmental interests. Because the six GCC countries share a similar political environment (Al Obeidli Reference Al Obeidli2020, 31), we hypothesize that our expectations will hold similarly across the GCC states; however, we will draw particular attention to nuances and differences among the countries in our analysis.

RESEARCH STRATEGY AND METHODS

As pointed out, media restrictions in the GCC countries apply equally to Arabic- and English-language outlets. Yet our focus is on English-language newspapers, since they have a stronger international outreach and cater to diverse audiences both domestic and foreign, including expats, migrant workers, Western diplomats, and more Western-oriented local elites. These outlets in the GCC—in contrast with their Arabic-language counterparts—thus provide a window into how the regimes want to present themselves both internally and to the outside world. However, the circulation of English-language newspapers is smaller than that of Arabic newspapers in the region. Their relative ability to contribute to domestic public opinion thus varies, being stronger in the UAE and less so, for example, in Bahrain, the KSA, and Kuwait. Still, the English-language press has a long tradition in the Gulf region, as a result of both British colonization and the Gulf's embeddedness in a globalized world. The reading of English-language newspapers is also a generational issue, with younger people generally consuming such outlets more than elders.

Although English-language newspapers are generally considered more liberal than their Arabic counterparts, they still significantly differ from each other. For example, in Saudi Arabia, Arab News “firmly supported women's right to political participation and freedom to drive,” and its women journalists have offices in the Jeddah headquarters’ main building (Sakr Reference Sakr2008, 398). By contrast, another KSA newspaper, the Saudi Gazette, is more conservative; at its headquarters, women work in a separate building from men and are often absent from daily meetings and decision-making (Sakr Reference Sakr2008, 398–99; both newspapers are part of this analysis).

Our data set covers the period 2008–17 because of a dearth of coherent data prior to 2008.Footnote 5 For each country, we selected at least two newspapers according to the following criteria: first, (whenever possible) the paper was established before 2000 to provide full coverage for the selected time span and to ensure it is an established media source in the respective country; second, the circulation rate is as high as possible; and third, publication is daily to allow for the maximum possible number of articles. Table 1 provides an overview of the selected newspapers by country.

Table 1. Overview of newspapers

Note: Since data availability for Oman and Qatar were limited, we added more newspapers to allow for adequate retrieval.

Source: Rugh (Reference Rugh2004, 61–62, 100), newspaper websites.

To include as many articles as possible, we drew up a provisional list of terms likely to be used in headlines or sub-headlines of stories about women in the context of their empowerment. We tested this list through a pilot study with a newspaper from another Middle Eastern country, the Jordan Times, unrelated to this research. This list comprised the terms woman, women, female, sheikha,Footnote 6 and minister (for a similar approach, see Al-Malki et al. Reference Al-Malki, Kaufer, Ishizaki and Dreher2012, xv). We conducted an automated search for headlines and sub-headlines including the terms in the 15 newspapers. Only articles that explicitly concerned women were selected and, if relevant, coded.

The coding manual assessed three different features of the analyzed headlines. First, diversity captures the arena of society—political, economic, civil, or religious—a headline was predominantly concerned with. This variable thus identified the main actor (collective or individual) in a headline, such as government officials, a company, a civil society organization, or a religious figure. Civil society and the economy in the Gulf region tend to differ greatly from the way they are commonly understood in Western democracies in terms of state involvement. According to Krause (Reference Krause, Held and Ulrichsen2012, 6, 21), civil society in GCC states occupies a fluid space between state and society and involves both formal and informal interactions and networks between citizens and the state. In this regard, we coded headlines that might fall in either the politics or civil society domain as the latter if no state actor (e.g., the ruling family, legislature, ministries, police, judiciary) was identified or plainly apparent. Concerning the public and private sectors in the GCC, Rutledge et al. (Reference Rutledge, Al Shamsi, Bassioni and Al Sheikh2011, 187) note that “many ‘private’ sector entities are partially or wholly state owned and are thus best considered as ‘quasi’-private sector companies as opposed to ‘real’ private sector ones.” We thus coded an article in the economic domain if its headline focused on the economy and related topics without mentioning state actors such as the government or state agencies, even though they may have been implicitly involved.

Second, valence assesses whether the evaluative tone of a headline was positive, negative, or neutral, indicating the extent to which the treatment of headline topics was polarized across the domains of society (see also Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2020). In this regard, headlines expressing either a normatively positive or negative evaluation or describing a positive or negative factual event involving women's empowerment are coded as either positive or negative, respectively. Neutral valence indicates that a headline was neither positive nor negative in either evaluative tone or factual content.

Finally, domestic/foreign origin differentiates between news of domestic and foreign origin, showing the extent to which GCC states cover foreign stories of women's empowerment. All reports from other GCC states were considered foreign.

For a detailed overview of the coding manual, see the supplementary material online, including example headlines for each coded dimension.

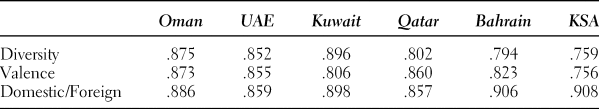

All codings were assessed separately to allow for the exploration of differences between countries and over time, as well as interrelations between the three features. Coders learned the coding schema with a corpus of headlines from the Jordan Times. Once inter-rater reliability of at least Cohens’ κ >.80 was reached, which indicates a reliably similar application of the coding scheme by the coders, two coders coded and double-coded, respectively, the headlines from each GCC country. To ensure that coders did not deviate from the manual during the process, a control inter-coder reliability was calculated on the basis of 25% of the headlines of each country (see Table 2). Disagreements were discussed and resolved by discussion after the independent coding was completed.

Table 2. Cohens’ κ values reflecting inter-coder reliability separated by variable and GCC country

DATA ANALYSIS

Across the GCC countries, we obtained 17,505 headlines that included one or more of the search terms. After eliminating the headlines not addressing women's empowerment issues (n = 7,790) and those reporting crimes (n = 3,002), 6,713 remained for further analysis. As the newspapers varied both in extent of relevant coverage and availability, the number of coded headlines differed among the six countries. For the UAE, 546 headlines were extracted from the Khaleej Times and 288 from Gulf News, for a total of 834 (2008–17). For Kuwait, 202 headlines were extracted from the Kuwait Times and 228 headlines from the Arab Times, resulting in 430 headlines (2011–17). For Oman, 541 articles were obtained from the Times of Oman, 176 articles from the Oman Daily Observer, 77 from the Oman Tribune, and 220 from the Muscat Daily, yielding a total of 1,014 headlines (2009–17). For Bahrain, we obtained 748 headlines from the Gulf Daily News and 452 headlines from the Daily Tribune/DT News, yielding in total 1,200 headlines (2008–17). For Qatar, 337 articles were provided by the Gulf Times, 253 by the Qatar Tribune, and 632 by The Peninsula, for a total of 1,222 (2009–17). For Saudi Arabia, 1,029 headlines were obtained from the Arab News and 983 from the Saudi Gazette, for a total of 2,013 (2008–17). For a detailed overview of retrieved news headlines per country per year, see Table A1 in the supplementary material.

To compensate for these differences in the total number of coded headlines per country, the absolute number of each of the three coding categories (diversity, valence, and domestic/foreign origin) was divided by the total number of coded headlines, yielding relative frequencies of each code for each country. Additionally, we combined the codes to determine in which domains of society women's empowerment is evaluated in positive, negative, or neutral terms, and to what extent the valence of media coverage of women's empowerment differs when the news headlines focus on the country of publication relative to such news from other countries.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Diversity, Valence, and Domestic/Foreign Origin across the GCC States

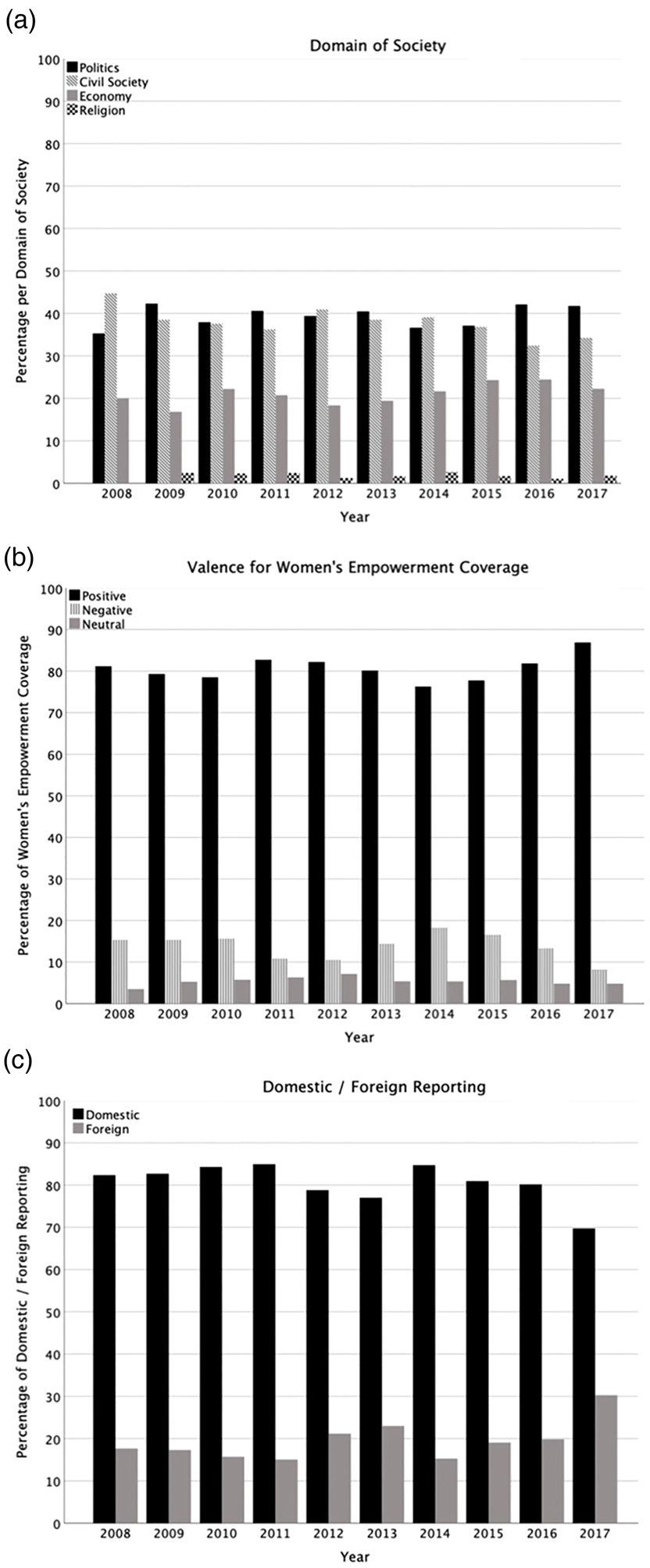

Starting with diversity, Figure 1a shows that a plurality of articles addressing women's empowerment in every year under study involved the domain of politics (for a detailed overview, see Table A2 in the supplementary material). On average across all GCC states, this category accounted for 40% of the analyzed headlines. Coverage of women's empowerment in this domain centered on the topics of women's rights and women's participation in the political sphere. It included how political institutions, governments, ministries, and courts addressed such issues as public and political equality rights, national identity, citizenship, and family status law. The political realm commanded the highest share of reporting on women's empowerment in Kuwait and the UAE (50% and 49%, respectively), followed by Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman (45%, 44%, and 33%, respectively). In Saudi Arabia, 31% of reports on women's role in society focused on the political domain. Although reporting in this domain was overall lower in the KSA than the other countries, coverage of women's political empowerment increased in Saudi Arabia over the years studied, especially during the Arab Spring of 2011–12, exceeding coverage in the civil society and economy domains. Altorki (Reference Altorki, Seikaly and Mattar2014, 98) has argued that while the Arab Spring “has undoubtedly had a certain impact on Saudi women,” the state remained determined “to promote its own image as a progressive force in society.” This, in turn, might explain the increased coverage in the political domain during this period. More generally, the Saudi press focused intently on the enfranchisement of women in municipal and shoura elections in 2015, as well as the approval of women's right to drive (in 2017) and, over several years, the role of male guardianship.

Figures 1a–c. Overview of diversity, valence, and domestic/foreign reporting across GCC states.

In Qatar, the newspapers referred more often than those elsewhere to sheikhas and princesses of the ruling family in the context of women's empowerment, casting it in conservative and traditional political terms. About 22% of 1,222 analyzed headlines (n = 267) mentioned a sheikha from the ruling al-Thani family. This finding corroborates Maktabi's (Reference Maktabi2016, 22) argument that “pressures for reforms that affect female citizens in Qatar come predominantly from the ruling al-Thani family and a political will to invest in education.” While Bahry and Marr (Reference Bahry and Marr2005, 107) observed that “Qatar is producing some striking new role models for the new generation of women,” Al-Malki et al. (Reference Al-Malki, Kaufer, Ishizaki and Dreher2012, 241) have argued that “one must be very careful about linking female pioneering to women's empowerment: ‘firsts’ for women come and go and are easy to rig and manufacture for the sake of headlines and political expediency.” This observation also applies to the many national women's days that are celebrated in addition to International Women's Day across the region. The example of Qatar's sheikhas reflects the Gulf states’ tendency to embrace female firsts and role models to advance or at times instrumentalize women's empowerment. While the power of role models to inspire and drive women's empowerment is undeniable, an inordinate focus on them may well inhibit the sustainability of such progress.

The civil society category accounted for 37% of the analyzed headlines across GCC states, though exceeding politics in the years 2008, 2012, and 2014 (Figure 1a). Topics in the civil society domain include but are not limited to civil organizations, media, art, music, and sports. Civil society actors thus range from political and social activists to artists and athletes as well as any citizens in their capacity as citizens. This domain's share of overall coverage was highest in Oman (45%), followed by Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain (39%, 37%, and 37%, respectively). For the UAE and KSA, headlines in the civil society domain amounted to 31% and 35%, respectively.

This result suggests two conclusions. First, despite the ruling families’ uniquely powerful positions, state-society relations in the case of women's empowerment are complex and multifaceted and not one-sidedly skewed toward the state in GCC countries, involving discourses beyond the immediate involvement of the government (Abouzzohour Reference Abouzzohour2021, 2). Second, coverage of the politics and civil society domains varies among the GCC states, underscoring the countries’ sociopolitical diversity despite their similar political systems (Al Obeidli Reference Al Obeidli2020, 31).

Although “civil society . . . holds little power” in Oman, the country was among the GCC states that were relatively strongly exposed to the Arab Spring in 2011 with protests reaching from Sohar to Muscat and encompassing different social strata (Abouzzohour Reference Abouzzohour2021, 4). The protests overall were reform oriented rather than bent on toppling the regime, and the sultan reacted with both mild concessions, especially limited civil reforms, and repression to deter further opposition (Abouzzohour Reference Abouzzohour2021, 3, 5). This mild opening in the civil sector in turn could explain the high rate of civil society coverage in Oman's newspapers. Furthermore, Kuwait's high ranking in this domain corroborates the analysis by al-Mughni and Tétreault (Reference al-Mughni, Tétreault and Sakr2004), who describe the country's relatively diverse civil society and media landscape.

To a lesser extent, women's empowerment was reported in the context of the economy, with 22% of overall coverage. In this domain, newspaper articles focused on topics such as the development of industries, companies and businesses and women's role in them, the female labor force, micro-loans for women, and entrepreneurship. Aspects of women's professional development, lifelong learning, and education were also addressed in this domain. The KSA had the highest share of women's empowerment articles in the domain of the economy (31%), followed by Oman (22%), the UAE and Bahrain (18% each), Qatar (16%), and Kuwait (10%).

The even distribution between politics and the economy in the corpus of KSA headlines is surprising. On the one hand, the KSA had the lowest employment rate of female nationals in the GCC—16% in 2014 (Buttorff, Al Lawati, and Welborne Reference Buttorff, Lawati and Welborne2018, 80). On the other hand, this very fact may have prompted media discussion of women's participation in the labor force and the economy. A newspaper analysis of Arab and Western representations of female trendsetters in Saudi Arabia showed that “the largest single concentration of stories (27) in [a] sample of 214 stories was about Saudi businesswomen” (Kaufer and Al-Malki Reference Kaufer and Al-Malki2009, 115). Saudi female students also outnumber male students in the fields of business and economics (Buttorff, Al Lawati, and Welborne Reference Buttorff, Lawati and Welborne2018, 71), which likely contributes to the high share of empowerment coverage that focuses on economics. This focus may also be a particular feature of English-language newspapers, with their expat and internationally inclined readerships—the attention paid to women's economic achievements may, at least in part, serve as window dressing to stave off Western criticism and enhance the state's international legitimacy (Al-Rasheed Reference Al-Rasheed2013; Tripp Reference Tripp2019).

Again, a strong focus on role models is apparent in the economic domain across a variety of industrial sectors, and women are evidently encouraged to become entrepreneurs and start up their own businesses. Yet the role of entrepreneurship in women's empowerment is ambivalent. While entrepreneurship means that women “take control of their own employment,” in the specific context of the GCC states, this often reinforces socially defined gender roles, since women “also fulfill sociocultural obligations of separation from men because they can work from home” (Kemp Reference Kemp, Madsen, Ngunjiri, Longman and Cherrey2015, 48). Owning mainly small family businesses, entrepreneurial women's business assets and networks tend to be relatively small as well, often excluding them from the major business networks of well-established firms (Kemp Reference Kemp, Madsen, Ngunjiri, Longman and Cherrey2015).

Finally, the last category, religion, constituted a total of only 2% of all women's empowerment stories. The topics addressed in this domain included religious practices and scholars voicing their opinion of women's role within religion, Muslim activism, the challenges of Islamism and religious fundamentalism, and other religions within the GCC states. Islam, the state religion of all the GCC countries, plays a central role in Gulf societies (Al-Rasheed Reference Al-Rasheed2013). In their study of the relationship between religiosity, Islam, and support for patriarchal values, Alexander and Welzel (Reference Alexander and Welzel2011, 258) found that “living in a dominantly Muslim society strengthens patriarchal values more than individual identification as a Muslim.” We found that issues related to women's empowerment and religion were hardly discussed in the newspapers, whether positively or negatively. This suggests that, while religion is a crucial topic in the context of women's empowerment in any society, official English-language GCC news outlets avoid spotlighting the nexus of the two concerns, with its highly inflammatory potential.

Overall, the share of articles related to women's empowerment that centered on religion was highest in the KSA yet was still only about 3% of its total articles. The controversial topic of women's driving—one of the empowerment topics most discussed in a religious context—will be explored further later.

Turning to valence (Figure 1b; for a detailed overview, see Table A2 in the supplementary material), the disparity between positive, neutral, and negative perspectives on the topic of women's empowerment is relatively low. (High polarization of valence is present when the levels of both positive and negative coverage are high and the level of neutral coverage is low.) In four of the six GCC states (the UAE, Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar), there was a very strong prevalence of positive reporting on women's empowerment across the social domains with 83%, 89%, 84%, and 88%, respectively, whereas neutral and negative reporting in these four countries was extremely low (4–5% and 7–11% of overall coverage, respectively). In contrast, in Kuwait the share of positive news reporting was a relatively low 74%, while neutral reporting (10%) and negative valence (16%) were consequently higher. This echoes the comparative analysis by Maktabi (Reference Maktabi2016, 26), who concluded that “Qatar is a far less politicized society than Kuwait.”

However, negative reporting was most prevalent in Saudi Arabia, at 23%. With 71% positive and just 6% neutral reporting, the KSA thus had the highest polarization of valence among the GCC states, indicating that public discussion about women's empowerment is most tonally dispersed. Both the KSA's Arab News and Saudi Gazette covered contentious topics, including the controversy over women's right to drive. We take a closer look at this topic since it has attracted much international attention.

Following a transitional period of almost a year, women have been allowed to drive in the KSA since June 2018. Women's demands to be permitted to drive are long-standing and hotly disputed. In 1990, 47 Saudi women drove their own cars in an effort to express their desire to drive, which was not illegal but very uncustomary at the time. The protest was stopped, and “a fatwa was issued declaring that women's driving was contrary to Islam” (Zuhur Reference Zuhur2003, 25). In 2011, protests renewed, led by the Women2Drive online campaign (Tsujigami Reference Tsujigami, Khamis and Mili2018, 150). However, it is important to note that “[i]t is not only conservative male members of society but many women too who [were] reluctant to see the ban on driving lifted” (Tsujigami Reference Tsujigami, Khamis and Mili2018, 157). Headlines from earlier in the study period reflect the intense debate: “Saudi Woman Caught Driving in Qassim” (Arab News, May 24, 2011), “Book on Women Driving Banned” (Saudi Gazette, March 14, 2014), “Women Should Not Drive in an Islamic Country” (Saudi Gazette, October 16, 2014), “Qur'an and Hadith Do Not Ban Women from Driving” (Saudi Gazette, December 14, 2014). In 2017, the headlines changed dramatically: “King Salman Orders Driving Licenses for Women” (Saudi Gazette, September 26, 2017), “Letting Women Drive in Saudi Arabia ‘Does Not Conflict with Sharia,’ Say Senior Scholars” (Arab News, September 28, 2017), “Driving Licenses for Women Will Boost Economic Growth in Saudi Arabia: Experts” (Arab News, October 5, 2017), and, finally, “Women Driving: Hectic Preparations Under Way” (Saudi Gazette, November 8, 2017). Coverage of the issue in the two newspapers, which was relatively polarized and frequently negative prior to 2017, became uniformly positive once the rulership announced its intention to lift the ban. Corroborating our analysis, Elyas et al. (Reference Elyas, Al-Zhrani, Mujaddadi and Almohammadi2020, 20), who studied Saudi newspapers and magazines through critical discourse analysis, evaluate this polarization of media portrayals of women's empowerment in the context of driving as a sign of social change in Saudi society.

In addition to diversity and valence, we also investigated to what extent the six GCC countries published domestic versus foreign news about women's empowerment (Figure 1c; for a detailed overview, see Table A2 in the supplementary material). Across the region, the vast majority (79%) of stories relating to women's empowerment were of domestic origin. Qatar's and Oman's newspapers had the highest share of stories involving women's empowerment with foreign origins, 30% and 29%, respectively. Kuwait's and the KSA's newspapers had the lowest shares, 8% and 12%, respectively.

While the ratio of stories of domestic versus foreign origin was steady over time across the GCC states, an intra-regional divide is apparent. Whereas newspapers in the UAE, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar all report regularly on women's rights developments in Saudi Arabia, Saudi newspapers largely focus on the GCC as a whole and only rarely incorporate reporting on other, individual Gulf states—for example, “Career Women in the Gulf: Changing Perceptions and Experiences” (Arab News, April 1, 2014). This indicates that the KSA, by far the most populous GCC country, is regionally more inward-looking than its neighbors.

Domestic/Foreign Origin of News: Combining Diversity and Valence

In this section, we focus on how diversity, valence, and domestic/foreign origin relate to each other. Combining the domains of society and the categories of valence results in 12 categories per country, while relating the domestic/foreign origin of news to the categories of valence results in two sets, domestic and foreign, each with three categories per country (see Tables A3 and A4 in the supplementary material).

Figure 2 displays the combinations of societal domain with valence across the six countries over time. Positive reporting in the political domain made up the greatest share of overall coverage in every year of the study (on average 32% across GCC countries and years), except for 2008, when it was edged out by positive reporting in the civil society domain (Figure 2). In fact, the political domain was the strongest source of positive reporting compared with the other three domains across the GCC states even increasing over time. The UAE and Qatar had the highest share of overall coverage from positive reporting in the domain of politics, with 42% and 40%, respectively. In total, the positive reporting across all countries indicates a highly affirmative public discourse around government policies and politics.

Figure 2. Grand total percentage of the combination of the valence of women's empowerment with diversity separated by year.

The positive political coverage in the UAE commanded the highest share of a given country's coverage among all 12 categories across all six GCC states (barely edging out the 41% share of all Omani coverage delivered by positive reporting in that country's civil society domain), suggesting that the UAE's press is the most governmentally affirmative in the Gulf region. In Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, we find that the highest share among the 12 categories was positive reporting in the domain of the economy at 25%, even higher than positive reporting in the country's political domain—setting the KSA apart from all other GCC countries. This reconfirms the strong focus of the Saudi press on the economy in the context of women's empowerment.

Negative reporting was more dispersed across countries, even though it was generally much lower than positive reporting in every country and domain. Over time across the GCC, negative reporting in the domains of politics, civil society, and economy, amounted to 6%, 5%, and 2%, respectively. Kuwait displays by far the highest negative reporting in the domain of politics with 9%. Polarization in Kuwaiti reporting was most pronounced in both that domain and civil society. This result—especially concerning the domain of politics, where governmental directions are discussed most directly—corroborates the evaluation of the Freedom House index (2020) and the analysis by al-Mughni and Tétreault (Reference al-Mughni, Tétreault and Sakr2004), who describe the country's relatively diverse civil society and media landscape as more independent from rulership than their counterparts in the country's neighbors. In Saudi Arabia, negative reporting in the domains of politics (7%), civil society (10%), and the economy (5%) all surpassed the regional averages, confirming that public discourse on women's empowerment is generally more polarized in valence in this country.

Neutral reporting was low across all countries and domains. For the domains of politics, civil society, and economy, it amounted to 1.5%, 3%, and 0.5%, respectively, across the six countries over time. These low numbers indicate that while stories of women's empowerment are mostly treated affirmatively in both news items and opinion pieces, it seems to be a topic that always invites an evaluation and is rarely a purely neutral endeavor. In sum, women's empowerment is hardly a topic of indifference in the region.

Finally, turning to the domestic and foreign origin of news headlines across GCC states, the vast majority (on average 79%) covered domestic news. The combination of these data with those on valence yields an interesting result. For example, while the share of positive reports about foreign compared with domestic news in the UAE was still very high (72% and 87%, respectively), the share of negative reporting about foreign news was almost three times that of domestic news (22% versus 8%). A clearly increased negative valence in relation to foreign news can be observed for Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar as well (with 16%, 19%, and 19%, respectively). Thus, news of a negative nature—either factual or opinion-related—are more often reported from abroad. While polarization of valence is generally low, there is a difference in how domestic and foreign news are covered, with reports of foreign origin displaying a stronger polarization of valence than their domestic counterparts. This finding corroborates recent scholarship on media landscapes in autocracies. Examining China's state-run news agency Xinhua, Brazys and Dukalskis (Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2020, 67), for example, found that its inward-facing coverage is “profoundly positive or at least nonpolitical” while outward-facing coverage stresses more “negative” or “contentious” news.

Only in Kuwait and the KSA do we observe an even distribution between the different valences concerning domestic and foreign news. Even more so, in Kuwait positive reporting ranges from 73% (domestic) to 88% (foreign) while negative reporting varies between 16% (domestic) and 12% (foreign). In the KSA, distribution of valence is likewise very even (positive: 70%/73%; negative: 24%/19%). In the context of women's empowerment, both Kuwait's and KSA's English-language presses treat domestic and foreign news similarly in terms of tone. This result suggests that relatively extensive coverage of international news (Qatar and Oman) does not necessarily indicate less polarized reporting. In sum, in four of the six countries, the reporting of foreign news demonstrated a more polarized valence than the coverage of domestic news.

While the empirical results clearly confirm our empirical expectations, we also identify important differences across the GCC countries. First, while we assumed that diversity in terms of topic discussion across the domains of society would be low because of the region's nondemocratic regimes and top-down media structures, a more nuanced picture emerged. Women's issues and questions of empowerment were indeed most often discussed in the domain of politics, confirming the strong link between state-led measures and women's empowerment in these countries. Yet, the fluid civil society sector, where governmental actors are not always immediately involved, fared strongly as well and in some years even surpassed the domain of politics. Interestingly, in Oman the civil society domain fared strongest, likely reflecting the influence of the Arab Spring, while in Saudi Arabia, reporting on women's empowerment in an economic context was on a par with coverage in the domain of politics and the highest share of such coverage in the region. Moreover, while religion plays an important role in all six countries, there were few references to it in the context of women's empowerment even in the KSA. In sum, the differences in coverage of the societal domains were more pronounced than anticipated both within each country and across the six GCC states.

Second, we assumed that the polarization of valence in terms of tonally positive, neutral, or negative reporting about women's empowerment would generally be low because the media in all six countries must adhere to governmental policies and directions. While this expectation was clearly confirmed for a strong positive valence, especially in the domains of politics and civil society, we also identified more variations regarding polarized valence, for example, in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

Finally, while our expectation that the majority of reports would be of domestic origin, as the media must further governmental policies and public support, strong variations became apparent between countries, with more of Oman's and Qatar's coverage involving foreign news than was true of the other GCC states. At the same time, and with the exceptions of the Kuwaiti and Saudi newspapers, press coverage was divided in terms of providing relatively more positive and fewer negative reports of domestic versus foreign events involving women's empowerment.

CONCLUSION

This article has shed light on both the relationships between GCC governments and the media and between GCC governments and their support for women's rights and empowerment. Women's empowerment functions as an important policy tool for Gulf governments to bolster nation-building processes, modernization, and economic diversification, as well as the regimes’ reputation and legitimacy, both domestically and abroad. Since the media is closely tied to the governments, media outlets provide a window into how GCC states want to present themselves both internally and to the outside world. In this regard, English-language press in these countries aims to reach broader audiences, both domestically and internationally, than does the Arabic press.

First, our analysis shows that while discussion of this topic derives from and is focused on the realm of politics and top-down executive and legislative measures, it also significantly involves the economic domain and the fluid spaces of civil society. Second, we found that women's empowerment was little discussed in the context of religion in any of the studied press outlets; this might hint at differences between English- and Arabic-language newspapers in the region. Third, while we expected that the valence of women's empowerment coverage would be largely supportive, with low polarization because of the non-free-media structure, our examination revealed several nuances, especially in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Finally, our analysis found a difference in press coverage, with more positive and fewer negative reports of domestic events involving women's empowerment in four of the six countries. The last point also confirms that although English-language media serves more internationally inclined audiences, it is equally bound to the state-media structure, with stronger positive reporting of domestic than foreign news.

Although our analysis has been the first extensive one of news coverage of women's empowerment in the Gulf region, it has clear limitations. Future research on the GCC states’ press should include Arabic newspapers to study whether and to what extent they diverge from English-language press in their reporting of women's empowerment and gender equality—e.g., especially in tone, conceptual and lexical framing, and specific topic choices; comparisons to other topical social issues should also prove fruitful. Also valuable would be an incisive investigation of the links between press coverage and factors outside of the press, for example, how and to what extent political or social developments interact with press interests. Given the increased importance of social media in the region (Seikaly and Mattar Reference Seikaly, Mattar, Seikaly and Mattar2014a, 6–7), social media outlets should also be included in future analyses to produce a coherent picture of the public debate on women's empowerment across different social strata in the GCC states. Finally, linking media more systematically to audiences and media consumption would help further illuminate the impact that the media may have on the broader society. Altogether, such research would allow for a broader understanding of the roles that the media and the press in particular play within the GCC politics and societies and the discourse(s) surrounding women's empowerment they forge.

Despite its limitations, our study contributes to the growing scholarship of women's empowerment in nondemocracies. It speaks to recent research at the intersections of women's representation in the media in autocracies and of autocratic media structures more generally. The combination of these research streams indicates that once nondemocratic governments incorporate the idea of women's empowerment into their political strategies, the media becomes an important transmission belt in furthering the legitimacy of and public support for women's inclusion and empowerment through positive and reassuring media portrayals. The greater polarization in the valence of coverage of foreign versus domestic news confirms this relationship. Our analysis shows that the public debate surrounding women's empowerment in the still very conservative GCC states is more diverse both within and across countries than often perceived from outside. The continued and still growing saliency of women's empowerment offers hope and an indication that the debates surrounding women's rights and equal participation in the GCC societies will remain intense and the research on these issues vital.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X21000465