In this short contribution, I argue that the growing research on post-industrial labor market inequality bears a strong—yet widely misunderstood—relevance for the comparative politics literature on the transformation of political party systems. More specifically, I contend that the assumption of “labor market outsiders” being equal to “globalization/modernization losers”—and therefore constituting the core electorate of right-wing populist parties—is largely mistaken. Rather, atypical work and unemployment is most widespread among service workers, whose primary electoral choice is to abstain from voting.

This implies that the fundamental and still ongoing reconfiguration of European party systems—through the rise of right-wing populist parties—is actually driven by workers in the manufacturing sector (the traditional “insiders”), rather than by labor market outsiders. They seem to vote for right-wing populist parties not primarily for reasons of labor market vulnerability, but rather because of a fear of relative decline. Hence, the rise of right-wing populist parties should not be interpreted in simple class-conflict terms as a mobilization of precarious labor market outsiders against the more privileged. In the light of the widespread electoral abstention of labor market outsiders, a crucial question for European party politics will be whether this growing group of voters will be mobilized electorally in the future, and if yes, by whom. Linking the study of labor market inequality more closely with research on changing party systems could provide the former with a broader relevance beyond comparative political economy, and the latter with a sounder micro-foundation.

The goal of this contribution is conceptual: it discusses both the main concepts of labor market vulnerability examined in political economy, as well as the main concepts of globalization/modernization losers proposed in the party literature. The paper then operationalizes these concepts empirically and shows that the losers from globalization are not congruent with labor market outsiders. In a second step, the paper looks at electoral choice.

1. Labor market inequality and new electoral cleavages

Labor Market Change in Post-industrial Societies Transforms Electoral Politics. At least two important strands of recent research would subscribe to this statement, but they approach it from opposite sides and, to date, almost entirely separately: the first strand of literature is the one on dualization and increasing labor market inequality, which is under close examination in this symposium. For about a decade now, scholars in political economy have been theorizing the political determinants and effects of growing inequality in the distribution of labor market risk between insiders and outsiders. When addressing the political relevance of labor market inequality, this literature usually takes a micro-level approach, starting from the effects of risk exposure on political preferences of individuals, and then moving upwards towards processes of preference mobilization, aggregation and—though rarely—representation (e.g., Häusermann Reference Häusermann2010; Rehm Reference Rehm2011; Lindvall and Rueda Reference Lindvall and Rueda2014). However, the literature on dualization, to an extent, got stuck in questions of conceptualization and measurement at the micro-level, thereby losing its focus on the wider political impact of labor market inequality.

The second strand of literature that would subscribe to the above statement is not in political economy, but in comparative politics. Over the past two decades, a hugely influential literature has demonstrated that electoral politics and party systems in Europe have been deeply transformed by the emergence of a socio-cultural dimension of political mobilization and conflict, which cross-cuts the traditional, economic left-right divide (notably Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Hooghe, Marks and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010). The (few) studies in this literature, which actually do investigate the micro-level foundation of this new divide argue that the continuously growing “traditional-authoritarian-nationalist” pole of this dimension (in the words of Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002) is built on the votes of “losers” of either modernization or globalization, whose vote choice can be explained to a large extent with reference to economic risk and hardship (Betz Reference Betz1994; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1997; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). Hence, this literature indeed takes a keen interest in labor market risk, but it adopts a top-down approach when studying it, starting from changes in the party system and then moving downwards towards socio-structural potentials. Consequently, the micro-foundation of electoral realignment has remained an Achilles heel of the literature on electoral realignment.

These two strands of literature have evolved almost entirely separately. Where implicit or explicit links between processes of labor market dualization and electoral realignment are made at all, the most straightforward assumption is that globalization/modernization losers are roughly congruent with labor market outsiders, and therefore, they constitute the key electorate of right-wing populist parties (e.g., Lubbers et al. Reference Lubbers, Mérove and Peer2002; Mughan et al. Reference Mughan, Bean and McAllister2003; King and Rueda Reference King and Rueda2008). However, this shortcut may well be too rushed. First, labor market risk is not a synonym of “cheap labor,” as it is a mechanism of stratification that is distinct from income (see e.g., Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Hacker and Schlesinger2012; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2015). Second, labor market vulnerability affects various segments of the working class to very different extents, with some of them being protected (insiders) and others exposed (outsiders). The implications of this incongruence between the “working class” and “outsiders” for political mobilization and electoral representation have remained direly underexplored. Regarding research on labor market dualization and insider–outsider divides, the focus has been on individual preferences (e.g., Burgoon and Dekker Reference Burgoon and Fabian2010; Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Hacker and Schlesinger2012; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2015), whereas the political aggregation and representation of these preferences, or the link between labor market risk and party choice have received much more scant attention.

Hence, comparative politics finds itself in a situation where different strands of theorizing and research investigate the same topic—i.e., the electoral behavior and mobilization of the “losers” of post-industrial economies—almost entirely separately, with substantial costs in terms of conceptual confusion and limited comparability of findings. Linking insights on dualization and electoral realignment may provide us with a sounder micro-foundation regarding the motivations that drive these processes of realignment.

In terms of starting an exploration of this question, I provide in the following an aggregated account of how labor market risk relates to the most prominent conceptualizations of globalization/modernization losers, and to party choice.

2. Comparing labor market outsiders and losers of globalization or modernization

How widespread is unemployment, temporary employment and part-time employment among losers (as opposed to winners) of globalization or modernization?

The definition and operationalization of globalization losers and modernization losers are contested in the literature. I use here the three main definitions available. Contributions in the field of International Political Economy (focused on globalization) tend to characterize as losers of globalization low-skilled workers in jobs that are exposed to international economic competition (e.g., Mughan et al. Reference Mughan, Bean and McAllister2003). I use here the operationalization proposed by Walter and Rommel (Reference Rommel and Walter2017) based on skill and the offshoreability of specific occupations. While some occupations can be delocalized in other countries, other occupations can be characterized as “sheltered.” I present the low- skilled sheltered here as relative globalization winners for the purpose of comparison to globalization losers.

In contrast, the comparative political economy literature focuses rather on occupational structural change as drivers of labor market changes and hence tends to privilege the term modernization losers. Interestingly, two distinct occupational groups can be conceptualized as primary losers of structural change. Given massive deindustrialization and skill-biased technological change (Oesch Reference Oesch2013), manual workers in manufacturing must be considered the main losers of structural change. This group corresponds to the traditional industrial blue-collar working class. At the same time, however, many European countries have seen since the 1990s the emergence of a growing service sector working class (Oesch Reference Oesch2013), which tends to be less unionized and whose contracts tend to be less well protected than the work contracts of the traditional industrial working class. Low-skilled service sector workers, even though they work in a growing occupational sector, can thus also be seen as losers of modernization. Hence, I look at both the routine service workers and the routine/skilled manual workers as possible losers of modernization. In contrast, I conceptualize high-skilled service sector workers (“socio-cultural professionals,” Oesch Reference Oesch2013) as modernization winners in terms both of a growing occupational sector and high levels of education, which are in stronger demand in post-industrial labor markets.Footnote 1

Table 1 displays the group-specific rates of unemployment (in the past 5 years) and atypical employment for all respondents of the European Social Survey (ESS) waves 1–5 in Western Europe. It highlights all groups that are affected more strongly than average by these three main forms of post-industrial labor market risk.

Table 1. Unemployment and Atypical Employment among Winners and Losers of Globalization and Modernization

Note: Pooled sample of all ESS respondents 2002–2010 (waves 1–5) in 16 countries (AT, BE, CH, DE, DK, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, IE, IT NL, NO, PT, and SE); N=146,596. ESS=European Social Survey.

The first finding from this simple cross-tabulation is that labor market outsiders and globalization losers are clearly two distinct groups. Low-skilled workers in offshoreable jobs are not affected more strongly by labor market vulnerability than the average population. The distinction between low-skilled offshoreable and sheltered occupations does not coincide with objective labor market risks. The correspondence between labor market risk and losers/winners from modernization is stronger, but also far from perfect. Both service workers and manufacturing workers are more strongly affected by unemployment than modernization winners. But in terms of atypical work contracts, we see that labor market vulnerability is not confined to the working class. High-skilled service workers have shares of temporary and part-time contracts that are comparable to those of the low-skilled workers in the service sector.

Table 1 clearly shows that routine service workers are most strongly and most negatively affected by labor market risk in post-industrial economies. Hence, if we relate the concept of labor market outsiders to occupational classes, we must think primarily of the low-skilled service class workers as outsiders, rather than the traditional blue-collar working class.

3. Labor market outsiders and electoral choice within the working class

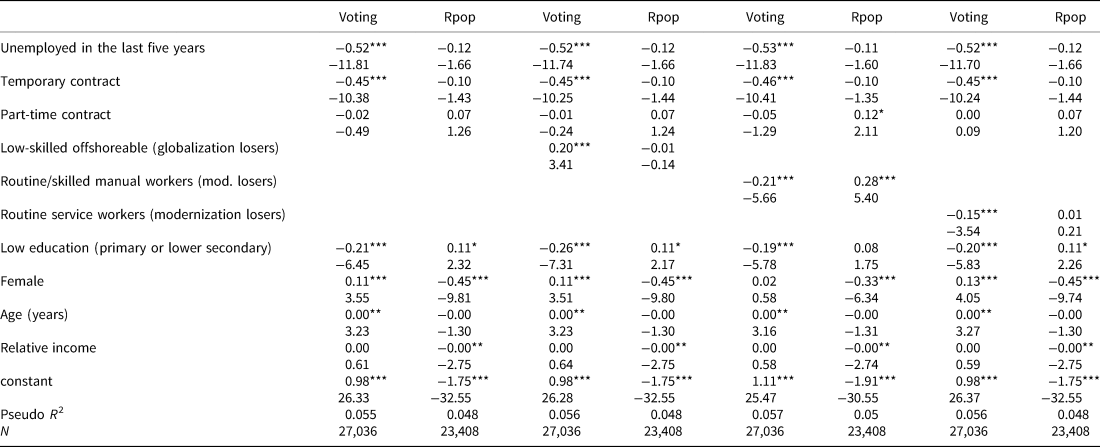

The next step is to look at the electoral behavior of these groups to test the assumption that labor market outsiders constitute the “traditional-authoritarian-nationalist” working class constituency of right-wing populist parties. To this end, I compare logistic regressions of vote participation and right-wing populist voting (as opposed to voting for any other party or abstaining) for working class respondents in the eight countries in the cumulative ESS file that have more than 100 respondents declaring they voted for a right-wing populist party. All models contain the three main forms of post-industrial labor market risk that characterizes labor market outsiders. In addition, I introduce the three groups of globalization/modernization losers sequentially.

There are two main insights in Table 2. First, within the working class, labor market risk is strongly related to abstention, but not to right-wing populist voting. Both the experience of unemployment and a temporary contract clearly, consistently and substantially increase the probability that an individual will not participate in the election. Part-time work, by contrast, is not related to abstention. None of these forms of labor market vulnerability predicts the vote for the populist right. Hence—and this is the second main finding—among the working class, it is not the “objectively” most vulnerable who vote for the populist right. This is also consistent with the finding in Table 2 that low-skilled service workers tend to vote less, but do not tend to vote for right-wing populist parties over-proportionally. Rather, it is the routine/skilled manual workers that tend to support these parties more frequently. Finally, Table 2 also confirms that globalization losers (measured in terms of offshoreability) are clearly not the electorate of the populist right.

Table 2. Determinants of Electoral Participation (Voting) and Right-Wing Populist Party Vote (Rpop) within the Working Class (Routine and Skilled Office, Manual and Service Workers)

Note: Table shows the coefficients and z-values; effects of country dummies not shown.

B Sign levels: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; pooled sample of all ESS respondents 2002–2010 (waves 1–5) in all countries with more than 100 rpop-voters (AT, BE, CH, DK, FI, FR, NL, NO). ESS=European Social Survey.

In sum, it appears clearly that labor market outsiders are not the main constituency of the populist right. There is no direct link between labor market vulnerability and the electoral choice of the workers most strongly affected by it. Rather, labor market outsiders tend to abstain from voting, and it is the skilled and routine manual working class (the traditional “insiders”) that supports right-wing populist parties over-proportionally.

4. Conclusion

My findings in this short contribution resonate strongly with the ones by Bornschier and Kriesi (Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Jens2013: 11ff), who investigate the working class vote for the populist right. They find that even within the manufacturing working class, “job insecurity and low education actually prevent individuals … from participating, rather than making them vote for the extreme right” (Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Jens2013: 22). Hence, labor market vulnerability does not explain right-wing populist voting. Rather, it is the traditional manufacturing working class that supports these parties strongly. Several recent studies also find evidence that the actual experience of unemployment or occupational precariousness is unrelated to right-wing populist voting (Kurer Reference Kurer2017). All these studies come to the consistent conclusion that the right-wing populist vote is not a direct reaction to the experience of economic hardship. Bornschier and Kriesi (Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Jens2013) suggest what they call a cultural mechanism to explain why the skilled manufacturing working class supports these parties most strongly: “while not being the worst-off social segment in post-industrial society, this group has experienced a relative decline as compared to the postwar decades, making it receptive to the culturalist appeals of the extreme right” (Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Jens2013: 26).

The above findings highlight the importance of investigating further the (non-)mobilization of labor market outsiders. One key question for European political parties seems to be whether this growing group of voters can at all be mobilized and—if yes—which parties would most likely win their votes. This seems to be an open question, as recent research found that the preferences of service workers tend to align with those of the production workers on matters of immigration, but at the same time they hold more favorable views towards welfare, social investment, and cultural liberalism (Ares Reference Ares2017).