Introduction

The Arctic archipelago of Svalbard is a part of Norway, but Russia has had a long-term presence on the islands due to the provisions of the Svalbard Treaty. Russian authorities have regularly made it clear that ensuring the continuation of this presence is a political goal. In recent years, Russia’s official rhetoric on Svalbard has sharpened, with officials and politicians accusing Norway of – among other things – placing illegitimate restrictions on Russian activities on the archipelago and alleging that Norway violates the Svalbard Treaty.

Although criticism is nothing new, recent critical statements have been sharper than previously. In a letter to his Norwegian counterpart on occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Svalbard Treaty, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov reminded Norway of its obligation to ensure the possibility of conducting economic activity under conditions of full equality. He expressed concern about several specific issues, including “the unreasonable extension of nature protection zones where economic operations are limited,” and called for bilateral consultations to lift the restrictions from the operations of Russian organisations on the Archipelago (Embassy of the Russian Federation in Norway, 2020). To this, Norway’s Foreign Minister commented, “Norwegian authorities can both regulate and prohibit activity, as long as it is done without discrimination based on nationality” (Søreide & Mæland Reference Søreide and Mæland2020).

In November 2021, Russia accused Norway of actions aimed at “including this territory in the sphere of national military development,” including “reception of reinforcements from NATO allies” (Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2021). And in October 2022, Russia again charged Norway with actions aimed at “consolidating Spitsbergen within its sphere of military activity” (Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2022). In September 2024, a statement from the Russian Foreign Ministry read “The Norwegian authorities continue to carry out their destructive policy of involving Spitsbergen in military planning and securing it in the zone of responsibility of the aggressive NATO bloc” (Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2024a). In all these protests, a major issue has been visits by Norwegian navy frigates and patrols of the Norwegian coast guard in Svalbard waters, but there have also been other items. In December 2024, with reference to Norwegian newspaper reports on possible military use in Ukraine of data downloaded at the SvalSat satellite station, it was alleged that “This is how Spitsbergen is turning into a range for testing dual use products and technology under the guise of defending its sovereignty” (Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2024b).

Such high-level criticism would seem to indicate deep Russian concerns about developments on these Arctic islands. But how strong is the Russian interest in the islands, really? Do Russian policies, plans and activities on Svalbard fit with the sharp rhetoric?

In this article, we try to answer these questions, by investigating Russia’s policy of presence on Svalbard. Our approach is based on the assumption that Russia’s Svalbard priorities, and the organisation of its presence, can indicate how strong the Russian interests are.

We also assume – as most scholars do – that the main objective of Russia’s Svalbard policy is to ensure that the islands cannot be used militarily against Russia (see next section). In the event of war, Russia would likely aim to control Svalbard. Such a war scenario falls outside the scope of our study, but given the topicality of the issue, we will revisit it briefly in the concluding section.

The focus of the study is on the Russian policy of presence and the concrete outcomes of this policy “on the ground.” Given the sharpening of Russian official rhetoric on Svalbard, and assuming that Russia’s policy on Svalbard is driven mainly by security concerns, we would expect our findings to be in line with the realist assumption of states as unitary, rational actors. In other words, we should expect this policy to be strategic in character, based on clear objectives and priorities, centrally coordinated, sufficiently funded and consistently implemented.

More specifically, we will address the following questions:

-

Are there firm plans for the Russian presence on Svalbard, and are such plans implemented?

-

Are Russian policies coordinated?

-

What role will coal mining play for the Russian presence in the future?

-

Do Russia’s research activities serve political purposes?

-

Who are the main actors in Russian Svalbard policies – what is the role of private companies and investors?

We draw mainly on Russian official documents retrieved via the internet to document plans, statements and decisions and provide some data. Various Russian media articles are used to support with data and some assessments. There is a plethora of Russian newspaper and internet sites dealing with Svalbard, or rather Spitsbergen, which is the name still used by Russia. Usually, they do not contain data or solid documentation, but there are exceptions. Such sources have been identified applying search phrases reflecting the various topics analysed. Sources used have been critically reviewed. Nevertheless, it cannot be claimed that they always are representative. However, the conclusions reached in this article do not rest on single sources. Russian academic works pertaining to the specific issues analysed are few and far between. No extensive academic research report covering developments in recent years has been identified, but some Russian academic works covering earlier periods are cited.

Recent international research literature has covered many issues related to Svalbard. Studies on military-strategic issues in the sea areas surrounding Svalbard have documented increased Russian as well as Western activity (Åtland & Kabanenko, Reference Åtland and Kabanenko2019; Wither, Reference Wither2021a). An increased interest in Svalbard geopolitics is discussed by Østhagen (Reference Østhagen2024). Concerning the Svalbard islands themselves, social science research has focused on such themes as the transition of Longyearbyen, the administrative centre, from a mining company town to a community dominated by tourism, research, and education (Pedersen Reference Pedersen2017), environmental and international change affecting governance of the islands (Kaltenborn, Østreng, & Hovelsrud, Reference Kaltenborn, Østreng and Hovelsrud2020) and the conditions for local democracy (Sokolíčková, Reference Sokolíčková2022; Brode-Roger, Reference Brode-Roger2023). Vold Hansen & Moe (Reference Vold Hansen and Moe2024) analyse development of Norway’s research policies on Svalbard. Only a few studies have examined the internal development in the Russian mining town of Barentsburg. Olsen, Vlakhov, & Wigger (Reference Olsen, Vlakhov and Wigger2022) and Middleton (Reference Middleton2023) compared demographic and socio-economic trends in Longyearbyen and Barentsburg, and also described development of business activities. Even if these contributions are important as background understanding of Svalbard, none of them deal with Russian policies for presence and their implementation. The present article aims to fill this gap.

The Svalbard treaty and the changing purpose of the Russian presence

The Svalbard Treaty (1920), often referred to as the Treaty concerning Spitsbergen, which the islands were called at the time, recognises “the full and absolute sovereignty of Norway” (Article 1) over the archipelago. Other states do not have extra-territorial rights on Svalbard, but the treaty stipulates certain conditions that would protect their interests. Citizens of all signatory states are granted equal access and the right to be admitted “under the same conditions of equality to the exercise and practice of all maritime, industrial, mining or commercial enterprises both on land and in the territorial waters” (Article 3). Thus, Norway is not permitted to discriminate against citizens or companies from other states in favour of its own citizens in these areas of activity. But all actors must observe “local laws and regulations” (Article 3). Thus, Norway, as sovereign, may regulate such activities, but on a non-discriminatory basis. Security interests are covered by a paragraph stating that Norway must undertake “not to create nor to allow the establishment of any naval base in the territories specified in Art. 1 and not to construct any fortification in the said territories, which may never be used for warlike purposes” (Article 9).

The Russian government did not participate in the negotiations on the status of the Spitsbergen islands after World War I, as it had not yet been recognised by the victorious powers. However, the resulting treaty expressly stated: “[u]ntil the recognition by the High Contracting Parties of a Russian Government shall permit Russia to adhere to the present Treaty, Russian nationals and companies shall enjoy the same rights as nationals of the High Contracting Parties” (Art. 10). The Soviet Union had initially objected to the Treaty, but in 1924 it unconditionally accepted Norwegian sovereignty, after Norway had granted formal recognition to the new Soviet government. It formally acceded to the Treaty in 1935, following broader international recognition of the USSR (Arlov, Reference Arlov1996).

International economic interest in Svalbard had spurred clarification of its legal status, but most foreign companies soon gave up the islands. The Soviet Union was an exception to this general trend. Soviet mining activities had started already in 1919, and in the early 1930s, a Soviet state company began to buy up coal assets from other companies. From this point, only Norwegian and Soviet companies had permanent mining operations on the archipelago. Soviet mining was consolidated in one company with operations in two mining towns – Barentsburg and Grumant. The development of a third – The Pyramid – began in earnest after World War II. These Soviet mining towns were established as self-sufficient settlements with little interference from Norwegian authorities, who had a very modest administration on the islands at the time.

Norwegian and Russian scholars agree that in this early period, the Soviet interest in Svalbard was primarily economic (Holtsmark & Portsel, Reference Holtsmark, Portsel and Holtsmark2015). Coal from the islands, transported to the Soviet mainland by sea, was an important contribution to industrial development in Northwest Russia, as railway capacity from the south was limited. But after World War II, security interests became the dominant driver of Soviet Svalbard policy.

Only in the north did the Soviet Union’s naval forces in Europe have relatively free access to the open ocean, but they had to pass between Svalbard and the Norwegian mainland. From the 1950s there was concern that Svalbard could be used for transit of bombers on their way to attack Soviet territory. By the 1960s, the Northern Fleet, based in ports on the Kola Peninsula, had become the most important Soviet naval fleet, and Svalbard’s location in the exit area to the deeper Atlantic Ocean via the relatively shallow waters in the “Bear Gap” between Bear Island and mainland Norway was obviously of considerable importance (Figure 1). The USSR followed developments on the islands closely, protesting against any activity or construction which could be deemed militarily relevant. The Soviet authorities argued that Article 9 of the Treaty prohibited any military use of Svalbard: that the islands must be completely demilitarised (Todorov, Reference Todorov2020). The Norwegian interpretation has been that Article 9 does not constitute a prohibition against all military activity, as it “pertains solely to acts of war or activities for the purpose of waging war, and to constructing naval bases or infrastructure that can be classified as fortifications. Defensive measures and other military measures are permitted” (Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2016).

Figure 1. Svalbard’s location.

The Soviet edginess gradually ebbed as the military relevance of the islands waned with the development of intercontinental missiles. However, the establishment of an airport in Svalbard took place only in the 1970s, after Norway had given the USSR assurances that it would be used exclusively for civil aviation, and with permanent Soviet representation at the airport – an airport of great benefit also for the Soviet communities (Østreng, Reference Østreng1977).

Soviet mining activities had lost their economic significance and became dependent on heavy subsidies, but the Soviet presence increased, although one mining town – Grumant – was closed in 1962. By the end of the 1980s, there were approx. 2500 Soviet citizens on Svalbard, but only some one thousand Norwegians. Apparently, such a large presence, even if loss-making, was justified by its role for Soviet security. Unsurprisingly, the costs vs benefits were not spelt out in any publicly available documents.

Russia’s attitude to Norwegian authority on Svalbard became more relaxed with the end of the Cold War and the subsequent dissolution of the USSR, but the fundamental Russian interest remained the same: ensuring that the islands could not be used militarily against Russia. Russia protested at the visits of Norwegian naval vessels and military transport aircraft conducting civilian tasks – but such protests were often just a formality, and sometimes Russia did not protest at all. Nevertheless, Russian politicians regularly criticised Norway’s Svalbard policies, alleging that the real objective of Norway’s expanding environmental regulations was to drive Russia away from the archipelago and that Norway was doing NATO’s bidding (Kvitsinskiy & Shtodina, Reference Kvitsinskiy and Shtodina2007; Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2010). Such criticisms were voiced mainly by members of the Russian Duma and regional politicians. This contrasts with the stream of protests in later years voiced by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

A heart of coal

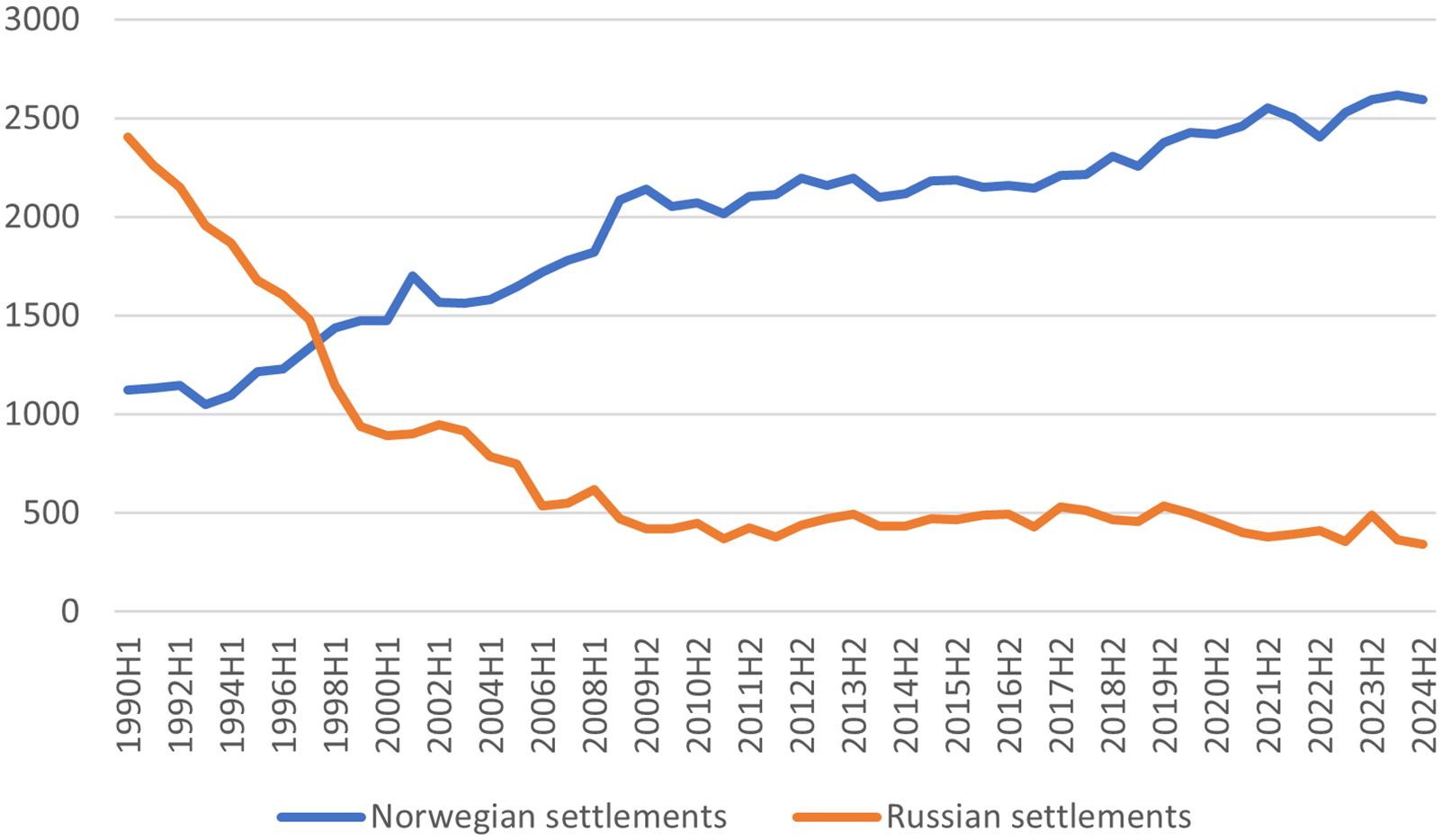

Russian activity on Svalbard was curtailed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, not as a deliberate policy but as an effect of the general economic crisis in Russia. The mine in the Pyramid was closed and the settlement was abandoned in 1998. The closure was probably compounded by the plane crash near Longyearbyen in 1996 where many leaders and workers from the Pyramid perished. The coal mines in Barentsburg experienced accidents and fires, attributed to lack of resources for new equipment and attention to safety measures (Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2010). The decay was highly visible, and the contraction was dramatic: The population in the Russian communities was reduced to about 500 by 2006. By contrast, the population in the Norwegian communities grew rapidly, soon outpacing Barentsburg by far (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Svalbard’s population. Source: Statistics Norway.

Even if Svalbard was not high on Moscow’s political agenda, Russian politicians occasionally referred to the importance of maintaining a Russian presence there. The state mining trust Arktikugol (“Arctic coal”) continued to be the main instrument for Russian state policies on Svalbard, but there was concern that the company did not fulfil its role. In 2005, the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation delivered a scathing report on Arktikugol’s use of financing received over the state budget (Russian Accounts Chamber, 2005). The report charged that nothing had been done to diversify economic activities despite advance warnings that the coalmine would soon be depleted; moreover, that the power plant was at risk of breaking down, which would require immediate evacuation of Barentsburg. The Accounts Chamber also noted that Arktikugol had misused state funds and had failed to report hard-currency earnings.

Clearly, something had to be done. In the course of 2006, three delegations from the Russian federal authorities visited Svalbard and Barentsburg, and the director-general of the mining company was replaced (Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2010). In 2007, a new “Government commission to secure the Russian presence on the Spitsbergen archipelago” was established, chaired by then-Vice Premier Sergey Naryshkin and composed of vice ministers from a series of ministries and directors of various state agencies. This new commission clearly had more authority than earlier bodies set up to develop Svalbard policies. It was given a broad mandate: to develop a unified strategy for the Russian presence, ensure coordination among state organs, and prepare proposals for the activity of Russian organisations on the archipelago (Portsel, Reference Portsel2012; Government of Russia, n.d.). When the Commission visited Svalbard in October 2007, Naryshkin declared:

[f]or us, Svalbard is a strategic site that gives us the opportunity to be present in the western part of the Arctic. Under the terms of the treaty, we must conduct economic activities here. With state-funded infrastructure, we would like to find activities that are self-sustaining (Netreba, Reference Netreba2007).

The commission indicated tourism, scientific research, fisheries, and fish processing, as well as services to the fishing fleet operating around the islands, as activities that could be self-financing, albeit with the state funding “social and engineering infrastructure” (Lakshina, Reference Lakshina2007).

Although the elements in the proposal were not entirely new, the high-level profile of the commission seemed to indicate that the scene was set for a revival of the Russian presence on Svalbard.

Notable changes did not take place immediately. A new “Strategy for the Russian presence on the Archipelago Spitsbergen until 2020” was confirmed by the Russian government only in March 2012. This document was not made public, but its contents were referred to in the Russian media. The overarching objective of the strategy was reported to be “optimisation, increasing efficiency and diversification of the economic activity” (Strategiya pomozhet, 2011). Already from 2009, federal funds were allocated to upgrade communications infrastructure in Barentsburg (Merkulov, Reference Merkulov2015). The coal mining company Arktikugol, which continued to be the main instrument for the Russian presence, had improved its operations under new management. But there was increasing consensus among Russian decision-makers that coal mining could not be the basis for Russian activities on Svalbard in the longer term (Portsel, Reference Portsel2012). Exactly how long it could continue was, however, disputed. Production was reduced to 120,000 tons per year to extend the lifetime of the mine. In 2023, it was announced that over a five-year period production would be brought down to a level sufficient for local needs – mainly the power station, some 40 000 tons, and that shipments of coal, mainly to Murmansk, would stop (Arktikugol planiruet, 2023).

There was no real interest in opening a new mine – which in theory could have been possible, as Arktikugol controlled mining rights in undeveloped areas, some not far from Barentsburg. The massive investment costs in projects that would be loss-making from day one effectively ruled out this option. Moreover, the mining company did not show any interest in exploring for other minerals. Instead Arktikugol, after some hesitation, presented itself as a vehicle for diversification of Russian activities.

The new director of Arktikugol (from 2022) declared his wish to expand the activities of the company, primarily in the field of tourism based in Barentsburg and the Pyramid, but also the possibility of investments in tourist infrastructure in Longyearbyen (Vesti Svalbard, Reference Svalbard2022; Na rossiyskom, 2023).

Diversification: tourism – a new element

Tourism had developed rapidly in Longyearbyen since the late 1990s, with some spillover to Barentsburg – mainly tourists and Svalbard locals using snow scooters in wintertime. The new leadership in Arktikugol after 2007 recognised that Barentsburg had a potential, and in 2008 the mining company established a tourism department. But development was slow, as the company had no experience or understanding of tourism. Then, in 2013, the department was reorganised into a separate division – Arctic Travel Company Grumant (ATC-Grumant). At the outset, ATC had only two dedicated employees, but in 2014, professional people were hired (Ylvisåker, Reference Ylvisåker2020). Soon, tourism flourished. Package tours – including dog sledging, visits to the coal mine and more – were offered, restaurants were opened, and facilities improved. ATC-Grumant worked together with the tourist association in Longyearbyen to attract guests. Most of them continued to be day-visitors, but also an increasing number of Russian tourists arrived, fascinated by the natural scenery as well as Soviet nostalgia in Barentsburg and especially in the Pyramid – a Soviet model city, frozen in the past, now re-opened for visits and overnight stays. The total number of visitors reached 37,000 in 2020, and income from tourism passed the revenues from coal. By 2019/20, ATC-Grumant had 80 employees in the peak season, and tourism was expected to continue to grow (Ylvisåker, Reference Ylvisåker2020).

The COVID pandemic that started in 2020 hit tourism on Svalbard hard – as elsewhere. Anticipating an end to the pandemic, ATC-Grumant did not lay off staff immediately, but revenues fell drastically. By 2021 the pandemic was still not over, and simmering political disagreements came to the surface. Several of the relatively young staffers who had been running tourism activities felt sympathy for Aleksey Navalny; the Russian opposition politician who was jailed after his return to Russia in early 2021, following treatment for a poison attack. Among them was the head of ATC-Grumant who left for Longyearbyen (Ylvisåker, Reference Ylvisåker2024, pp. 28–33). Several others did the same or returned to Russia, and this was a big setback for the Russian tourism effort. By 2022, however, such problems had become overshadowed by boycotts following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Cooperation with Norwegian tourist organisations ceased; individual visitors to Barentsburg were advised by Norwegian operators not to spend money there (Straumsnes & Andreassen, Reference Straumsnes and Andreassen2022). The number of visitors was sharply reduced, to some seven thousand in 2023 (Trutnev, Reference Trutnev2024). Visitors from Russia, travelling via Norwegian airports need a visa, and since Norway stopped issuing tourist visas to Russian citizens, only 17 Russian tourists arrived in 2023, and even fewer were expected in 2024 (Neverov, Reference Neverov2024). Arktikugol applied for direct charter flights for tourists from Russia, but Norway only gave permission for individual flights transporting staff of the mining company (Zagore, Reference Zagore2023).

Despite these setbacks, tourism is still regarded as a major component of continued Russian presence on Svalbard. In 2022, Arktikugol was transferred from the Ministry of Energy to the Ministry for Development of the Far East and the Arctic – a change connected with the move away from coal. Aleksey Chekunkov, the minister in the latter ministry was quite candid about his priorities. According to him, the future of Arktikugol should not be built on coal. He envisaged a change in the raison d’etre of the company, seeing a big potential in tourism. He noted the attraction of Barentsburg and the Pyramid as “time capsules,” in addition to interest in the northernmost inhabited place on earth. But to develop tourism, improvements in general infrastructure – estimated to cost some 1.5 bill rubles (ca. USD 24 million, as of October 2022) – were urgently needed, as well as new tourist infrastructure. For the latter, he counted on private investors (Zadera, Reference Zadera2022).

The organisation of future activities had not been decided – notably, whether privately owned tourist companies will be given a freer position, but Chekunkov expressed reservations about the capacity of the coal company: “It is not in its prime. Its life juices have been drying up decently in the latest period” (Zadera, Reference Zadera2022). He explained that a new director had been appointed for the coal company – a person without background in the mining industry, but with extensive business experience – to facilitate the transition away from coal (Zadera, Reference Zadera2022).

As of 2024, Arktikugol continues to control most of the activity in Barentsburg. Russian state funding of the presence on Svalbard is channelled through the company. The line in the Russian federal budget, “Subsidies to Russian organisations to ensure activity on the archipelago Spitsbergen” in reality concerns transfers to Arktikugol, which uses the funds to cover deficits in its own operations as well as maintaining infrastructure in the mining settlement. Even though government regulations list legitimate uses of the transfers in detail (Government of Russia, 2021), calculation of the total transfer is simple in the extreme: the difference between Arktikugol’s revenues and expenditures.

The transfers since 2013 (see Figure 3), reflect the economic situation of Arktikugol and not any specific government priorities. Transfers fell gradually from a level of 660 million rubles in 2013 to 465 million in 2019. These were the years when tourism grew and provided revenues that improved the company’s balance sheet. Then, in 2020 and particularly 2021, tourism income fell sharply due to COVID-19 and had to be compensated by higher federal subsidies. By 2022 costs had been cut, as many workers and tourist staff had left, and government subsidies were reduced. The budget was increased again for 2023, reaching 951 mill rubles (Ministry for Development of the Russian Far East and Arctic, 2022). This could be attributed partly to inflation, but probably mainly to reduced sales income for Arktikugol. The subsidies for 2024 were on the same level, but they were increased substantially for 2025 – in ruble terms – to 1.9 billion rubles. Inflation is clearly one factor, but also a lower ruble exchange rate. Arktikugol has many expenses in foreign currency – Norwegian kroner – which must be compensated by higher ruble subsidies. But seen in light of expected lower transfers in 2025 and 2027, an urgent need to repair and upgrade the power plant in Barentsburg is a probable explanation.

Figure 3. Subsidies to Russian organisations to ensure activity on the archipelago Spitsbergen. Source: Russian federal budget, corresponding years. 2036-27 is a budget prognosis.

Russian research activities

Besides coal mining, scientific research has been the most significant Russian activity in Svalbard. After a downturn in the 1990s, financing of research activities – much of it channelled via Arktikugol – picked up in the 2000s. It included projects in such scientific fields as geophysics, meteorology, glaciology, and archaeology (Merkulov, Reference Merkulov2015). Only in 2014 did the Russian government formally decide to establish a research centre in Barentsburg – collecting what was already going on and attempting to coordinate activities. In addition to the scientific justification for such a centre, the political aspects were highlighted: “Development of fundamental and applied research is among the [most effective forms of Arctic activities] and that correspond most closely to the national interests of the Russian Federation” (Government of Russia, 2014). It was foreseen that about ten Russian research institutes would be involved in the research activity. From 2016, activities were organised under a permanent “Arctic scientific expedition” managed by the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute in St. Petersburg, belonging to Roshydromet under the Ministry of Natural Resources (Government of Russia, 2016).

The new structure was intended to coordinate all Russian research activity on Svalbard. In fact, the various institutes involved in the centre and all those belonging to various state structures have continued to operate quite independently. Moreover, institutes under the Russian Academy of Sciences working in Svalbard do not seem fully engaged in the work of the centre; and their researchers generally stay in a separate building, “Research Station Barentsburg,” which is managed by Kola Science center (Kuleshov, Reference Kuleshovn.d.). Research activities are financed via the “Inter-agency programme for scientific research and monitoring on the archipelago Spitsbergen,” which has a long list of specific projects (Monitoring centre for coordination of the activities of the Russian research centre on the Spitsbergen archipelago, 2022).

Figure 4 shows the main categories of research activities and indicates stable budget allocations for the period 2018–2021, with an increase for 2022. More surprising is perhaps the almost unchanging distribution of funds among the various research areas. This would seem to indicate that funds are not used to target specific projects and that the budget allocations have been negotiated at an earlier stage. Most of the money is used to pay Arktikugol for infrastructure and services, less than half is dedicated to research activities as such. The “jump” from 2021 to 2022 is not explained in the interagency programme for 2022, but a possible reason may be that much of the costs to be covered are in foreign currency – Norwegian kroner – and that the ruble sums were increased to compensate for the very low ruble exchange rate when the programme was approved in March 2022. There was also a relatively bigger increase in geological and geophysical research. For 2023, the total allocation increased again, to 218 million rubles, without any specific explanation and less detailing of the distribution of sums (Monitoring centre for coordination of the activities of the Russian research centre on the Spitsbergen archipelago, 2023). In any case, the sums are very small – less than USD 1 million per year for the research projects, and slightly more for infrastructure. It seems that most of the personnel costs are covered by the research institutes themselves. Indeed, the impression from the interagency programme is more of a collection of individual projects developed by specialised research institutes than any overarching strategic vision, even if the programme emphasises the need to concentrate financial resources. Research activities are regularly justified by their political importance: “A permanent and active presence of Russia in this region secures its full participation in the resolution of international questions connected to Spitsbergen” (Monitoring centre, 2022). In Russian Svalbard policies, research is an activity on par with other activities that help sustain the Russian presence.

Figure 4. State financing of Russian research activities on Svalbard 2018–2022 in current million rubles. Source: Inter-agency programme for scientific research and monitoring on the archipelago Spitsbergen. Categorization of activities by authors.

New uncertainties emerged in 2023 with statements from the director of Arktikugol, supported by the Minister for the Far East and the Arctic, about establishing a “multi-disciplinary international scientific research centre” that would attract researchers from BRICS countries. (Minvostokrazvitiya zayavila, 2023; Zadera, Reference Zadera2023). The statements were widely cited in foreign media, but there was no official announcement, let alone decision about such plans. Arktikugol announced, however, that it had formed a “strategic partnership” with the Northern Arctic Federal University in Arkhangelsk for training of specialists, education and information about Svalbard and cooperation in establishment of a centre for researchers from BRICS countries (Northern Arctic Federal University, 2023). Arktikugol would take responsibility for construction and servicing of infrastructure. By autumn 2023, it was announced that the main activity of the centre would be in the Pyramid (Negrutsa, Reference Negrutsa2023). The idea of a centre was discussed in a working group on cooperation in oceanic and polar research organised under the Russian chairmanship of BRICS in Murmansk in June 2024, where a senior official from the Ministry of Education and Science voiced strong support (Nachalo sozdaniya, 2024).

According to the director of the research centre in Barentsburg, scientists from China as well as Turkey expressed an interest working in Barentsburg during visits in the summer of 2024 (Ugryumov, Reference Ugryumov2024). He did not comment on foreign interest in a centre in the Pyramid, and it is plausible that the management of the research station in Barentsburg is concerned that plans for a new centre in the Pyramid would divert resources from Barentsburg. For the coal mining company, the primary interest is to increase revenues from renting out buildings and providing infrastructure services, like it already does to existing Russian research activities. It remains unclear why countries such as China and India, which already have permanent research activity in the “research village” of Ny-Ålesund together with scientists from many nations and with infrastructure heavily subsidised by Norway, should want to establish an additional research centre in Barentsburg or the Pyramid, unless Russia pays for it. Given the overall thrust of Russian Svalbard policies, where new earnings – not new expenditures – are at the forefront, such largesse seems improbable.

Fish processing

Proposals for establishment of a fish processing plant in Barentsburg have been put forward several times since the 1990s and were a key element in the diversification of activities proposed by the government commission in 2007. In 2009, the head of the Russian fisheries agency announced that a decision had been made: an important justification was that “Russian business should make a strong footprint on Spitsbergen” – but he would leave building of the plant to Norway, because “this state has very strict environmental legislation. It is simpler for Norwegians thеmselves to observe these laws to the point” (Na Shpitsbergene v poselke, 2009). The plan soon encountered resistance, however, as the fundamental commercial assumptions were questioned. Could a plant located in Barentsburg ever be cost-efficient, compared to deliveries to ports in Norway or Russia? But despite such questions and criticism from the Accounts Chamber on the project development (Schetnaya palata, 2009), funds for continued preparation were allocated and plans were submitted to Norwegian authorities – who, however, did not grant approval (Merkulov, Reference Merkulov2015).

After a period of standstill, the project got moving again from 2012. A Russian fisheries company with a subsidiary in Norway was put in charge. They hired Norwegian engineers and architects, and meetings were held with the Governor of Svalbard. The basic concept was changed several times – from processing of demersal fish (groundfish) and shrimp to pelagic fish for the Russian market, and later a focus on high-value species, storage and export of snow crab and king crab. The latest version would involve a much smaller plant and looked more realistic. But in the autumn of 2021, just before the mandatory impact assessment was about to start, the project developer announced that the project had been put on wait because the development costs were too high, and it was uncertain whether the project would meet the strict environmental regulations on Svalbard (Ylvisåker, Reference Ylvisåker2021).

A year later, however, the director of Arktikugol was optimistic that the plans would proceed (Volkov, Reference Volkov2022). But the only relatively concrete step taken was the announcement in 2023 of a ship repair facility under the auspices of Arktikugol in Barentsburg, where the port has reportedly been made deeper (Na Shpitsbergene organizuyut, 2023). It is unclear how extensive are the repairs and services that can be offered, but being able to carry out some repairs in Svalbard makes sense in a situation where Russian fishing vessels are denied access to Norwegian shipyards, their traditional service provider (Trutnev, Reference Trutnev2024).

The Russian presence on Svalbard – strategic action, or fight for survival?

From the late 1980s, official Russian policy for the presence on Svalbard had been static. Arktikugol was left to its own devices, receiving only a minimum of subsidies to uphold production – and activity. Changes in the external security environment had scant impact on Moscow’s Svalbard policies. Serious Russian rethinking only began when depletion of the Russian coal mines became critical, and under-investment in infrastructure resulted in accidents and loss of life.

Diversification became the solution for the Russian policy of presence, as laid out by the Naryshkin Commission in 2007 and reiterated in the 2012 Strategy. Bold statements have since been expressed by politicians and in official Russian documents, but actual policy implementation leaves a mixed impression. Despite some partial successes, diversification has not proceeded very far, and coal mining has continued to be the core activity.

Among the activities singled out for driving diversification away from coal – tourism, fish processing and scientific research – tourism stands out as the most promising, despite recent setbacks. Interestingly, the initiatives have come from enthusiastic local staff – not official plans and directives.

Where fish processing is concerned, there has been no development at all, despite years of trying. The commercial prospects for a full-scale plant are very uncertain – as has been the case all the way. Nevertheless, there has been significant funding for planning; most likely because the Federal Fisheries Agency has promoted it strongly. Some actors in the Russian fishing industry also seem to have expressed interest. One speculation is that players in that very lucrative sector may expect that by supporting and providing subsidies out of their own pockets for a plant in Barentsburg, welcomed by Russian authorities, they could get access to fish quotas elsewhere. Exchanging quotas against desired investments is not unknown in this sector (Stölzel, Reference Stölzel2022).

Scientific research has been a persistent feature of the Russian presence and is expected to continue to be so in the future. Despite the establishment of a research centre, activities have been weakly coordinated, characterised by competition – not cooperation – among scientific institutions. For the authorities, the volume of activity seems to be more important than the content of the research projects – indicating that the financial support of Russian scientific research on Svalbard is largely politically motivated. The main drawbacks of scientific research as a diversification strategy are the limited potential for growth and – importantly – total reliance on state funding. Plans for an international research centre are not promoted by Russian science, but by the coal mining company in a speculative bid to obtain revenue from foreign institutions.

The Russian authorities have repeatedly called for self-financing activities on Svalbard. They do not want to keep subsidising unprofitable coal production and certainly have no interest in investing in new mines. In fact, there is a growing consensus that coal mining will come to an end. Debate is emerging on the future role of the coal company Arktikugol, which has been the primary tool of the Russian state on Svalbard. Should it continue to control new areas of activity, like tourism or perhaps fish processing – or be reduced to an infrastructure company? Aleksey Chekunkov, the Russian Minister for development of the Far East and the Arctic, who received responsibility for Arktikugol in 2022, has voiced scepticism about the company’s capacity to renew itself: “The ‘gift’ Arktikugol was a complex one – a company that had been suffering losses for decades, with a worn-out infrastructure, with personnel mainly from Ukraine, mining low-quality coal …” (Chekunkov, Reference Chekunkov2023).

Various statements, also from the company itself, have called for attracting private investors. This is particularly relevant in the tourism sector – the only new area of activity which has seen some success. Would such investors, if they were found, be satisfied working as subordinates to Arktikugol? Or would they demand more autonomy? So far, the development of tourism has been under the auspices of Arktikugol – but with external professionals firmly in the driver’s seat.

We have shown that Russia’s policy of presence on Svalbard does not stand out as particularly well-coordinated. Many different actors are involved in policy formation and polices must be viewed in part as outcomes of an ongoing tug-of-war between interest groups. This is borne out for instance by the complex relations between the research institutions in Barentsburg, and by the repeated allocation of budget funds for the commercially dubious and much-criticised fish processing project. Moreover, our examination of policies over the last two decades shows that economic constraints are a recurring factor. This, along with poor coordination and an unwillingness to make clear priorities has hampered the implementation of plans.

Overall, the impression is that Russia’s policy of presence is not particularly strategic – beyond an increasing openness to exploring new ways to sustain a sufficient presence. The relative success of the re-orientation of Norwegian activities in Longyearbyen is an inspiration, but financial limitations can be expected to continue to constrain initiatives that require major Russian state investments. The search for new activities and solutions must be seen as driven primarily by the need for cost-cutting and consolidating a limited presence – not as strategies aimed at increasing Russian influence on the archipelago.

The unquestioned goal of maintaining a presence for security reasons underlies Russian policy on Svalbard, and the totality of activity must be seen primarily as an instrument for achieving this objective. How large the presence should be and what form it should take have not been defined. It is hard to connect specific activities to Russian security interests, although attempts are made when budgets are negotiated.

Conclusions – and caveats

It is a peculiar situation that Russia, not as a state but through economic actors, is entitled to a sizeable presence on the territory of a foreign country – moreover, a member of NATO. The harsh, sometimes quite unpleasant rhetoric against alleged Norwegian violations of Article 9 serves as a constant reminder of the Russian interest. Russian interest is also expressed in ways beyond the purely rhetorical. A parade in Barentsburg on 9 May 2023, celebrating the victory in World War II looked from the outside more like a Russian political demonstration (Staalesen, Reference Staalesen2023). Similarly, the erection of a giant Orthodox cross in the Pyramid a few months later, in defiance of environmental regulations, had clear political connotations (Nilsen, Reference Nilsen2023). (The cross was later moved, after intervention from the Governor.) In 2024, Arktikugol hoisted large Soviet flags in Barentsburg and near the Pyramid, said to be part of the appeal to nostalgia tourism, but also interpreted as an expression of great power ambitions (Nilsen, Reference Nilsen2024).

Given Svalbard’s location, one might expect Russia to maximise its possibilities there. In practice, however, the Russian presence has been modest. Compared to the late Soviet period, the number of personnel has been radically reduced – from about 2500 to around 350 as of 2024. We must conclude that the basic Russian security interests are satisfied by what is in fact a quite limited presence. It is hard to see that there is any development on the islands that could constitute a security threat to Russia and it would seem that also Russia recognises Norway’s close adherence to the Treaty’s Article 9 on not establishing military infrastructure. The current abysmal relations between Russia and its Western neighbours, Norway included, can probably explain much of the harsh rhetoric from Russian officials against Norwegian policy, as well as the even more aggressive media discourse about Russia’s historical rights and interests on the archipelago.

The main insight from this article is that the practical policies to sustain the Russian presence have been weak and uncoordinated. Finance has remained a limiting factor for Russian activities. All the new ideas for developing a Russian presence will require substantial investments. We draw the conclusion that Svalbard is not as high on the Russian political agenda as the official statements might suggest.

Another major insight is that the practical policy of presence is not centrally directed and cannot be explained in a unitary rational actor perspective. The various activities and initiatives must rather be understood as expressions of sub-national interests, with actors having considerable freedom of action within an overarching goal to sustain the presence.

Russia interacts with Norway on Svalbard on two levels – the national political level and the local level. Russian protests on the national level have been directed at alleged Norwegian attempts to undermine Russian economic activity, notably by enforcing strict environmental regulations and establishing protected areas and restricting the use of helicopters.

This is fully in line with Soviet and Russian policy over the years to obtain as much freedom of action as possible, even though it recognises Norwegian sovereignty. Such Russian statements are not directly affected by financial limitations, there is little direct cost complaining to Norway. But there are other factors that probably limit Russian inclination to launch activities that defy regulations. Regulations and adherence to them is not exclusively a Norwegian-Russian question. If Norway were to give in to Russian pressure and ease regulations – new rules would have to apply to subjects of all signatories of the Svalbard Treaty. Until now, only Russia, in addition to Norway, has been interested in subsidising a presence of some size. This has given Russia a quite comfortable position. The overall level of activity on the islands is low and it is easy to monitor developments. Moreover, the restrictive environmental policies implemented by Norway, which Russia sometimes protests, have made the islands even less attractive for economic activities by other countries – which is in Russia’s interest on a strategic level.

A bilateral situation is clearly desirable for Russia. Overt expansive or provocative behaviour is likely to catch the attention of other states. It would be highly undesirable if other Western states, notably the USA, decided to become more active on Svalbard. Russia will have much to lose by upsetting the status quo.

Russian policy vs China on Svalbard is a case in point. A broader Chinese engagement is quite likely to attract US attention, and the overtures to Chinese institutions to become involved in Russian research could possibly have such consequences. According to the reasoning above, this would not be in Russian interest. An explanation of this paradox could be that the situation looks different at the national and local levels. The research centre initiative is coming from below, that is Arktikugol, where the finer calibration of international relations is not part of decision-making. But even if federal policymakers, for example in the Foreign Ministry should be against such a development, they can in the present situation not openly cancel the plans and risk problems with China. All they can hope for is that the BRICS centre plan will die by itself because of the financial and organisational challenges. But when it comes to Chinese engagement generally, it is of course not up to Russia to decide, but China itself.

On the local level, there is another factor limiting Russian wishes to be disobedient vs Norwegian authorities. Local Russian actors on Svalbard – whether the coal company or the consulate – realise that even if they can sometimes enjoy strong vocal support from Moscow, developing economic activities over time requires good relations with the Norwegian authorities and cooperation with partners in Longyearbyen. According to the Governor, the presence and inspections by Norwegian government and regulatory agencies in Barentsburg have increased considerably over the last fifteen years, in addition to the regular meetings with the governor himself and his staff (Rapp, Reference Rapp2023).

The present study has been confined to tangible Russian activities on Svalbard, and the policies underlying the Russian presence there. The conclusion is that there is a considerable distance between Russian rhetoric and realities. Russia’s policy of presence of Svalbard does not imply any coordinated expansionist Russian designs on the islands.

Still, some caveats are in place. The study does not cover Russian security policies more broadly, or the specific issues concerning the maritime zones around the archipelago. Moreover, our analysis rests on the assumption that, on the strategic level, the Russian authorities have a realistic understanding of the constraints and benefits of the Svalbard Treaty – even if local actors are given more freedom to explore economic opportunities.

In the event of an open confrontation between Russia and NATO, it is unlikely that Svalbard would remain unaffected. It is logical for Russia, and not only Norway, to make contingency plans for such a scenario. Some commentators have suggested that Russia might consider a “preventive strike” against Svalbard (Wither Reference Wither2021b). But it is very doubtful that Russia could achieve much militarily or strategically in such a scenario, and confrontation with NATO would be very likely. Russian military actions on Svalbard would in principle not differ from actions towards other NATO territories.

It has been suggested that, while overt military action directed against/on Svalbard is improbable, various forms of hybrid actions are thinkable (Nilsen, Reference Nilsen2021; Østhagen, Svendsen, & Bergmann, Reference Østhagen, Svendsen and Bergmann2023). Such actions are by definition deniable and can be low-level, complicating allied response. Speculations will persist, but it is hard to discern a rationale except in connection with an imminent military confrontation between Russia and the West.

Indeed, it is natural, and necessary, to discuss and assess threat scenarios in a situation where Russia has launched a war against one of its European neighbours. But it is also important to establish empirical facts about Russian policy and behaviour.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for comments from Andreas Østhagen in an early phase of the project and for insights shared by Norwegian officials involved in the administration of Svalbard, none of whom share responsibility for the conclusions in the article. Helpful suggestions from two anonymous reviewers are acknowledged.

Competing interests

The authors of the article have no conflict of interest with the content.

Financial support

This article is a product of the research project “Interdisciplinary Research on Russia’s Geopolitics in the Black Sea and the Arctic Ocean,” financed by the EEA and Norway Grants EEA-RO-NO-2018-0532, with additional funding from the Norwegian Ministry of Defence.