No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 January 2009

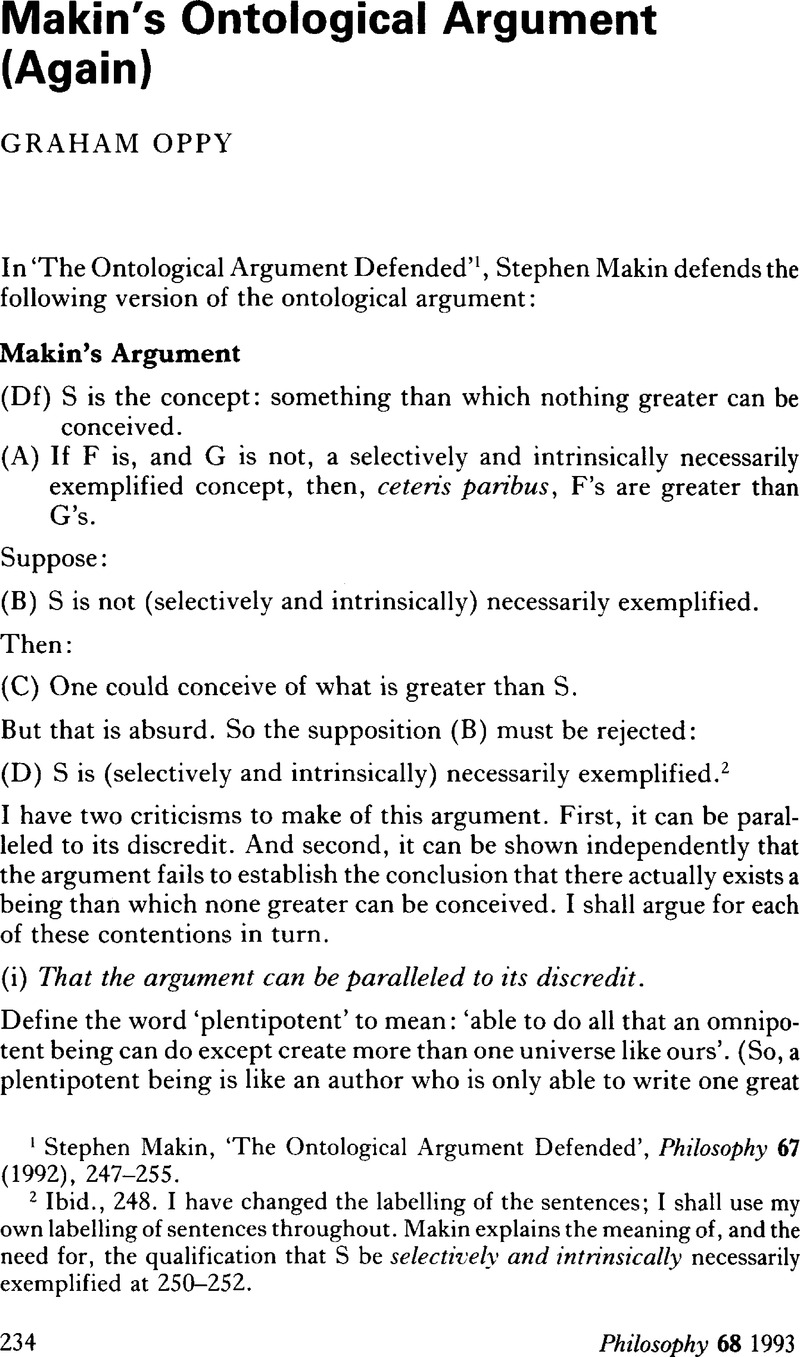

1 Makin, Stephen, ‘The Ontological Argument Defended’, Philosophy 67 (1992), 247–255.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 Ibid., 248. I have changed the labelling of the sentences; I shall use my own labelling of sentences throughout. Makin explains the meaning of, and the need for, the qualification that S be selectively and intrinsically necessarily exemplified at 250–252.

3 Here, I assume that it is greater to be the sole creator of the universe than it is to be one among many creators of the universe. If this assumption is rejected, then the joint existence of S and S0 may not entail any contradictions. However, it seems to me that it would be absurd to believe in the extraordinary number of necessarily existent beings which could be shown to exist by arguments just like the one discussed in the text.

4 Oppy, Graham, ‘Makin on the Ontological Argument’, Philosophy 66 (1991) 106–114.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

5 I include the condition that K is a kind whose members would be greater if they existed necessarily than if they merely existed contingently in order to avoid the (possible) objection that there are some kinds—e.g. vile and malevolent beings—whose members are not greater if they exist necessarily than if they merely exist contingently. Perhaps it will be objected that the kinds solvent and soluble substance fail to meet this condition. However, I fail to see how there could be any non-question-begging defence of this view. (For those who do see merit in this objection, re-run the argument using the kinds soccer goal-keeper who is (psychologically) unable to take penalty kicks and soccer penalty-taker who is (psychologically) unable to play in goal. Also, consider the kinds: defender of free trade and defender of tariffs together with the assumption that a defender of X than which none greater could be conceived would certainly be able to make a knockdown case for X!)

6 If there were only one substance, it could be both perfectly soluble and perfectly insoluble. But, given that there are different substances, it is impossible for the perfectly soluble substance to be the perfectly insoluble substance. And we know that, in the relevant sense, there are different substances.

7 Op. cit. note 1,249.

8 My original statement of the argument involved some ugly neologisms, which may have proved a distraction.

9 Others might prefer to describe the equivocation which I detect in Makin's argument as a kind of use/mention confusion. This is clearer if we reformulate the argument in terms of descriptions rather than in terms of concepts. (‘S is the description: something than which nothing greater can be described.’ Etc.) It seems evident that such a reformulation could do no damage to the argument.

10 I include a subscript in (C) because ‘concept of’ is equivocal in just the same way as ‘necessarily exemplified’.

11 The case against (ii) is given in my previous article. The case against (i) is a straightforward extension of the cases discussed in the text.

12 As my concluding remarks indicate, there is much else that Makin, op. cit. note 1, says about Oppy, op. cit. note 4, with which I disagree. However, I shall (need to) forgo any discussion of that further disagreement.