In June of 2022, the Netherlands committed to halving its nitrogen emissions by 2030. Since the country’s biggest source of nitrogen is dairy farming, the Dutch government introduced a voluntary buyout program that would pay dairy farmers to stop farming. Under the program, which was financed by a €24.3 billion transition fund, thousands of farmers would be paid “more than 100% of the value of their farms to quit.”Footnote 1

Governments overseeing large-scale labor transitions in an effort to attain important social objectives is nothing new. Yet the means by which governments are now willing to facilitate these transitions is more unprecedented. States are increasingly able and willing to pay workers to stop working when this proves socially beneficial—either in response to industry-specific negative externalities, as with dairy farming in the Netherlands, or in response to new growth opportunities provided by technological change, as with the labor-saving potential of automation and artificial intelligence.

Paying workers to stop working in these circumstances may be efficient in strictly economic terms, if the negative externalities outweigh the private benefit to individual workers. Yet what we refer to as “wage buyouts” are controversial, as they run up against deep-seated feelings around work that relate to identity, community, and established ways of life. The Dutch government learned this at its expense when its proposal was met with nationwide protests. One of the affected workers neatly summed up the prevailing feeling among the protesters, declaring that “I don’t want a bag of money from the government. I just want to do my job.”Footnote 2 Meanwhile, an earlier poll suggested that a full 40% of Dutch farmers would in fact be willing to abandon their business if offered the right compensation.Footnote 3 Which of these stances prevails on average? This article tackles the question by deriving testable expectations over how workers’ attitudes to (non)work vary across individuals, and how these attitudes might respond to structural threats.

This discussion speaks to a number of important current debates, from decarbonization and just transition to technology-driven labor displacement. The Dutch initiative is far from an isolated case. The Flemish government has similarly vowed to address its own nitrogen runoff by reducing pig farming by 30%, setting aside a €3.6 billion transition fund for its own farmer buy-out. Analogous initiatives have arisen to tackle overfishing: Australia and New Zealand have been buying out fishing vessels and permits (Holland, Steiner, and Warlick Reference Holland, Steiner and Warlick2017), effectively paying fisherman to stop fishing. In an effort to address climate change and health problems due to burning coal, countries including Canada, Australia, Germany, Poland, and India have proposed a range of buyout schemes of coal workers, aimed at phasing out coal-fired power plants (Gazmararian and Tingley Reference Gazmararian and Tingley2022; Meckling and Nahm Reference Meckling and Nahm2022; Gaikwad, Genovese, and Tingley Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022; Grausz Reference Grausz2011).

Social objectives other than environmental protection can also call for paying citizens to stop working. In the face of the COVID-19 global pandemic, a number of advanced economies furloughed employees in high-risk work environments in exchange for salary support, in an effort to prevent the spread of the virus.Footnote 4 Looking ahead, governments seeking to deliver on the potential of artificial intelligence, such as self-driving long-haul trucks, may also need to facilitate a large-scale transition towards an increasingly automated economy in the face of resistance from trade unions and workers. There, too, negotiated settlements that pay workers in legacy industries to stop working could prove economically efficient, if they can facilitate transition (Korinek and Stiglitz Reference Korinek and Stiglitz2018). How successful are such wage buyouts likely to be? Theory provides two views with diametrically opposed expectations. These are best thought of as ideal types. The difference between them comes down to whether they treat work as a means, or an end. The first view, which is aligned with both classical thought and contemporary economic orthodoxy, treats work as little more than a necessary means of earning a living.Footnote 5 Under this premise, workers should welcome any scheme that does away with the necessity of work, while still providing them with a livelihood. The corresponding expectation is that jobs could be readily substituted for monetary compensation.

The second view, commonly associated with a sociological approach, highlights the social function that work has taken on in modern societies. In this telling, individuals build their personal identities around their occupation. They derive meaning from their work. So much so, that holding a job has become a social requirement. In this vein, scholars like Lamont (Reference Lamont2002) have brought attention to the “dignity of the working man,” arguing that blue collar workers, in particular, value the self-sacrifice that hard work represents. Much has thus been made of the social cost of the labor dislocation over the last decades in former industrial strongholds, like the U.S. rust belt and Appalachian region (Hochschild Reference Hochschild2018). Beyond economic losses, these accounts emphasize a loss of identity and meaning ascribed to work, often looking to archetypal “single industry towns,” which have borne a disproportionate share of economic dislocation due to both globalization and automation (Hanson Reference Hanson2021), and where work and community are intrinsically tied together. A related literature in sociology also offers evidence of entrenchment in response to structural threats, whereby workers show increased attachment to, and identification with, beleaguered industries, and thus greater reluctance to leave them (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez2001; Strangleman Reference Strangleman2001). If work plays this wide range of social functions, then it follows that simply sending workers a check for ceasing work when it serves overall social welfare may not be viewed as adequate. A government program offering to do so may even be seen as an affront (Kolben Reference Kolben2021).

These two theoretical approaches offer contrasting testable implications. According to the first, individuals should eagerly take up an opportunity to retain their wages without having to work for them. Those with harder, more physically demanding work, moreover, should be more open to such programs than those with less gruelling, and more intrinsically fulfilling occupations. According to the second, workers might be reluctant to lose the self-worth, personal identity, and social recognition that their jobs represent. And this may be especially true of those blue-collar workers whose jobs are most threatened by structural factors, but for whom work is an especially important source of personal identity and socially-derived meaning.

The debate is of political significance. A number of right-wing parties have taken a vocal stance on worker buyouts, which they decry as instances of technocratic governments curtailing the freedoms of “hard-working people.”Footnote 6 The Dutch farmer protests, for instance, have garnered the support of major populist leaders, including U.S. President Donald Trump, the Polish right-wing Law and Justice Party, as well as the French far-right leader Marine Le Pen.Footnote 7 These populist politicians have invested heavily in the narrative propounded by the sociology-inspired literature that views work as a source of pride and duty to society. The fact that such criticism has systematically come from the political right raises a question about whether attitudes to (non)work vary systematically across the political spectrum, or whether these attacks are less about the social meaning of work, and more about the central role that technocratic government agencies have played in these initiatives. Insofar as we can disentangle these factors, the question becomes, to what extent do wage buyouts represent an opportunity for right-wing political entrepreneurs to capitalize on a gap between a technocratic view of (non)work and actual public attitudes?

We take up this nexus of question through three preregistered surveys on a combined quota-valid sample of 7,500 U.S. respondents.Footnote 8 We pose the question in its sharpest form, asking respondents whether they would agree to stop working if they continued receiving a wage, and we vary different parameters of the scheme. The results offer three major takeaways. First, the resistance to wage buyouts is real: while a majority of respondents are open to giving up their jobs if they continued to receive the same salary, a full quarter of respondents would reject it. Strikingly, respondents are significantly more open to a (randomly assigned) program design that would cut their working hours by half, versus an equivalent program that would cut their working hours completely—even as both offer the same take-home pay. These findings are consistent with the notion that on average, work offers individuals benefits that go beyond a wage. Yet program design matters: when the check is said to come from the government rather than the former employer, wage buyouts see significantly more resistance.

Second, individual attitudes to (non)work vary systematically along several parameters. Partisanship and political ideology appear strongly related to attitudes towards wage buyouts, with those on the political right showing significantly greater resistance. Yet upon closer examination, this is driven more by aversion to government programs than by attitudes to (non)work. By contrast, Protestantism is indeed consistently associated with reluctance to cease work, even following a lottery windfall.

Third, the findings challenge the view according to which manufacturing jobs, “working class” occupations, and jobs threatened by structural conditions are associated with more entrenched identities around work. On the contrary, individuals whose occupations are threatened by either offshoring or automation show lower identification with their work—even controlling for income, education, and ideology. These same respondents are accordingly more willing to accept government compensation for giving up their jobs. Manufacturing workers appear more likely to accept compensation than those working in service industries. Similarly, mining is associated with the single highest level of openness to wage buyouts.

Our null findings prove equally interesting. Skill level does not appear systematically related to attitudes towards wage buyouts: more educated respondents are neither more nor less likely to accept compensation in return for giving up their work. No geographic region is associated with more or less openness to labor compensation schemes. And while rural areas correlate with higher resistance, this relationship disappears once we control for partisanship. Finally, while the ethnographic literature highlights the relationship of men to their work, we find no consistent difference between men and women in their attitudes towards (non)work. This is not to say that men are not resistant to wage buyouts; rather, it’s that women seem opposed at roughly equivalent levels.

These findings carry considerable implications for both theory and policy. Much of the recent sociological study of work emerged in response to an economic orthodoxy that reduced work to a paycheck. The findings in this article confirm that treating work as a strictly economic activity that can be readily replaced by government compensation is misguided. But in correcting for this mistake, the risk is that scholars fall prone to a romanticization of the economic heartland, portraying male, rural, blue collar, and manufacturing workers as unresponsive to economic incentives because of an idiosyncratic attachment to work for work’s sake. Resistance to receiving “a bag of money from the government” fits within this narrative of working class honor. The evidence suggests that as social and market pressure grows to reduce employment associated with negative externalities—be it nitrogen runoffs, carbon emissions, public health consequences, or economic efficiency—resistance to wage buyouts would decrease, rather than rise over time. The policy implication is that there may exist a “bittersweet spot” in terms of timing, where individual resistance to wage buyouts decreases to the point where wage buyouts become achievable, while their social benefits remain sufficiently high.

Theoretical Framework: Work and Non-Work

Social progress often requires large-scale labor transitions, where workers must shift from one economic sector to another. In the past, the driving forces behind such transitions have typically been technological change and trade. The insight that governments might play a role in smoothing such transitions appears early. As far back as 1743, Sir Matthew Decker proposed compensating workers negatively affected by trade liberalization for the rest of their lives if necessary, as a means of pushing forth a socially beneficial reform: “Let their salary be continued to them upon the same foot they have it now, or during their lives, and this perhaps would induce them to look with a favorable eye on our design [of liberalization].”Footnote 9

Wage Buyouts versus Welfare Schemes and Universal Basic Income

Decker’s eighteenth-century proposal is useful in distinguishing wage buyouts, the focus of this article, from two other policy schemes that are similar, but raise very different theoretical and policy considerations: welfare programs and universal basic income (UBI) programs. In the first case, the various programs that fall under the broad umbrella of welfare policies typically kick in following layoffs. In most cases, these programs are also not meant to offer full income replacement, precisely to motivate workers to return to the labor force. Since welfare program design varies widely, the delineation is not always clear. The U.S.’ Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA), which offers trade-displaced American workers income support, retraining assistance, and medical coverage, is designed to facilitate labor transition to more competitive sectors (Kim and Pelc Reference Kim and Pelc2021a). It is also described as a way of reducing resistance to trade liberalization—that is, a means of “buying out” interest groups who lobby against trade reforms that are thought to benefit the country as a whole. While both TAA and Decker’s eighteenth-century proposal are thus geared at surmounting resistance from import-competing workers to trade liberalization, the latter fits the definition of a wage buyout, since it is an offer that workers must accept ex ante; while the former falls more squarely under the umbrella of ex post welfare provisions.

In the second case, UBI programs have become an increasingly popular policy proposal, with a number of countries trying out pilots on subsets of their populations to assess the costs and benefits of these schemes. Unlike welfare programs or wage buyouts, UBI provides a guaranteed income to all citizens regardless of their employment status. In other words, the main distinction is that UBI, as the term suggests, is universal. It depends neither on the consent of beneficiaries, nor does it demand that these beneficiaries stop working (though UBI proponents often argue that allowing people the option of not working may have desirable social effects (Standing Reference Standing2017)). Wage buyouts thus aim at a different objective from both welfare and UBI programs: they are an incentive scheme designed to get workers to stop working when this would be net beneficial, either by reducing negative externalities, or attaining efficiency gains.

While they deal with distinct policy instruments, the study of welfare and UBI nonetheless offers a number of useful insights. Most directly relevant may be the large literature on the embedded liberalism thesis, which holds that as governments pursue liberalizing reforms with distributional consequences, they will be required to spend more to compensate those “left behind.” Building on Ruggie (Reference Ruggie1982), this literature has progressed from correlating government openness with increased spending, to efforts at setting out the micro-foundations of labor compensation programs. These studies have examined attitudes among voters footing the bill for compensation (Hays Reference Hays2009; Rickard Reference Rickard2023), which has been shown to depend in part on the perceived likelihood of being among potential recipients (Ehrlich and Hearn Reference Ehrlich and Hearn2014).

The embedded liberalism literature has largely operated under the implicit assumption that those eligible for compensation will readily accept it. Yet more recently, a string of studies has begun questioning this premise. These have pointed out that recipients are often unaware of compensation programs, and fail to apply for them (Kim and Pelc Reference Kim and Pelc2021b), and that even those workers aware of labor transition programs mistrust and sometimes actively oppose them, often on social and cultural grounds (Kolben Reference Kolben2021; Gazmararian and Tingley Reference Gazmararian and Tingley2023). The implication is that more ambitious government initiatives, designed to convince workers to stop working in exchange of compensation, would face even greater resistance. Building on this literature, this article examines the limits of labor compensation by asking how potential recipients perceive the offer of worker buyouts that promise to make them “whole.”

Past Wage Buyouts

While wage buyouts have grown increasingly frequent of late, one sector that has long relied on measures resembling wage buyouts is agricultural policy. Throughout the postwar period, various schemes were introduced to support farmers and to meet conservation objectives. In the first case, farmers would be paid not to farm, as a way of limiting overproduction and keeping prices high (Orden, Paarlberg, and Roe Reference Orden, Paarlberg and Roe1999). In the second, compensation would be offered to farmers to retire land from production in order to conserve soil, water, and wildlife resources. For instance, the U.S. Soil Bank Program, established under the Agricultural Act of 1956, was aimed at both objectives. Since a wave of reforms in 1992, the European Union has implemented analogous initiatives under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) as a way of mitigating overproduction, responding to international trade pressures, and reaching conservation goals (Garzon and Garzon Reference Garzon2006).

As better information about the full social externalities of a number of large-scale agricultural practices emerge, cases of governments offering wage buyouts to attain conservation objectives have multiplied. In the 1990s, Florida thus successfully bought out a large share of its dairy industry to protect waterways in the Everglades (Schmitz, Boggess, and Tefertiller Reference Schmitz, Boggess and Tefertiller1995). The U.S. Department of Agriculture then proposed doing the same to reverse damage to the Chesapeake Bay watershed (Ribaudo, Savage and Aillery, Reference Ribaudo, Savage and Aillery2014). A recent proposal has called for an analogous buyout of alfalfa farmers in Utah, given findings about how alfalfa releases nitrogen into the soil, instead of absorbing it like most other crops.Footnote 10 In all these cases, the negative externalities of an economic activity are thought to outweigh its direct economic benefits. As the editorial board of the Salt Lake Tribune put it: “alfalfa has become a greater liability to the overall Utah economy and environment than it is worth.”

Analogous proposals have been made to shut down U.S. coal-fired power plants by compensating all affected workers.Footnote 11 Looking ahead, similar arguments may apply to truck and taxi drivers following the advent of self-driving vehicles, which promise to significantly improve fuel efficiency and reduce emissions.

In sum, governments appear to be resorting to wage buyouts with increasing frequency. This increase is likely driven both by “pull” and “push” factors. On one hand, growing awareness of the externalities imposed by some industries has led to more demand for large-scale government intervention. On the other hand, governments are now better able to use data and predictive models to calculate the precise trade-offs between the costs of buyouts and their social benefits. Such technocratic capacity may grant governments to greater legitimacy when implementing wage buyouts.Footnote 12 Since the COVID-19 pandemic, especially, governments have been increasingly willing to offer furloughed workers compensation on an unprecedented scale (Bennedsen et al. Reference Bennedsen, Larsen, Schmutte and Scur2020); policies that would have been unthinkable a decade ago, like UBI, have entered mainstream policy discourse. Finally, it is no coincidence that most wage buyouts have occurred in developed countries: these are the countries that have the required fiscal capacity to borrow against future savings to offer workers large compensation packages in the present. As more countries enter this category, we can expect wage buyouts to become more prevalent in agriculture, fossil fuel sectors, and industries affected by rapid technological change.

Across these different settings, governments can intervene by paying workers in a way that facilitates transition and accelerates socially beneficial change. The question is, will workers accept such proposals, or reject them out of hand? In other words, do workers just want to do their job, or are they open to quitting their work in exchange of “a bag of money from the government”? Despite the rising importance of this question, the existing scholarly literature provides no clear answer. Yet two scholarly approaches to work nonetheless offer relevant insights that inform our expectations. These can be distinguished by whether they treat work primarily as a means to a paycheck, or as an end in itself that holds intrinsic benefits.

Two Ideal-Type Theories

Work as a means. Classical thinkers considered work as an unfortunate necessity that had to be endured. In Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics, work is ideally avoided to allow for more worthwhile human ends like leisure and philosophy.Footnote 13 In the most common narrative, this remained the dominant Western view among elites until the emergence of the Protestant Ethic recast labor and professional diligence as moral virtues and signals of individual piety and salvation.Footnote 14

In this respect, neoclassical economics shares the assumptions of classical philosophy. Most neoclassical labor supply models posit that individuals derive utility from consumption and leisure, while work is considered a disutility. As W. Stanley Jevons, one of the economists associated with the “marginalist turn,” put it in Reference Jevons1871, “we labor to produce with the sole object of consuming.” The optimal labor supply decision thus balances the marginal utility of income earned from working with the marginal disutility of foregone leisure. Similarly, the labor-leisure budget line, still a standard feature of microeconomics textbooks, treats work strictly as a source of income. Under this premise, if workers could receive the same income without having to work, they should always prefer maximal leisure.Footnote 15

Another important aspect of the economic view of work is that it pays little attention to the source of income. That is, whether the check comes from an employer in return for a day’s work, or from a government assistance program should not matter to individuals. This premise has informed what has been called the prevailing technocratic approach, or the “establishment view,” which holds that people who lose their jobs to structural change can be made “whole” by some combination of transition adjustment and welfare support (Roberts and Lamp Reference Roberts and Lamp2021). And since most labor imposes a physical cost, while leisure does not, the orthodox economic approach would expect workers to opt to give up work if given the chance to do so at no income loss.

Work as an end. A more recent literature, with roots in sociology and social psychology, offers a contrasting view that highlights the intrinsic benefits of work. In this telling, work is a means by which individuals form a personal identity. It shapes their social networks and it offers a sense of meaning within a community (Ghidina Reference Ghidina1992; Silva Reference Silva2019). It is a source of honor, dignity, and a duty to the rest of society (Lamont Reference Lamont2002; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2018). In opposition to the economic literature, these intrinsic benefits are often said to come precisely from hard work—they arise not in spite of the difficulty of physically demanding and sometimes risky occupations, but precisely because of it.

This scholarship often pays special attention to blue collar, working class, or unskilled workers, likely because these groups have been most exposed to labor dislocation, as a result of a decades-long process of deindustrialization and urbanization in Western economies. The subjects of these studies often hold physically hard, repetitive, and sometimes risky jobs, as exemplified by the sociological literature on “dirty work,” which consistently finds that even those engaged in work judged “distasteful” or of “low quality” nonetheless derive considerable pride, satisfaction, as well as a sense of identification with their jobs (Deery, Kolar, and Walsh Reference Deery, Kolar and Walsh2019; Ashforth and Kreiner Reference Ashforth, Kreiner, Dik, Byrne and Steger2013). For instance, a recent study of the butcher trade in the United Kingdom finds that the dirty aspect of work can, by itself, become a factor that members of the group use to distinguish themselves from others, and that they may in fact bemoan the “cleaning up” of the trade, and express “nostalgia for the old, dirtier ways” (Simpson et al. Reference Simpson, Hughes, Slutskaya and Balta2014, 763). Consistent with the rest of the field, they emphasize a shared sense of “sacrifice” that comes from the “physicality” of work. As Hochschild (Reference Hochschild2018) insists on describing the views of her Louisiana interview subjects, work is precisely not about the result: “‘Hard’ is the important idea. More than aptitude, reward, or consequence, hard work confers honor” (158, emphasis in original).Footnote 16 While this scholarship differs widely in the occupational groups and regions it examines, the implication is that the arduousness of work need not decrease individuals’ attachment to it; it may in fact do the opposite.

As opposed to the economic view, the literature that highlights the social value of work also shares a belief that the source of income matters: people who derive their self-worth from hard work also tend to “reject any kind of dependence on the state” (Silva Reference Silva2019, 11). Indeed, the same individuals who draw dignity and honor from their work are described as most resistant to government support, viewing it as degrading. Hochschild (Reference Hochschild2018) describes one of her subjects as boasting of never having drawn an unemployment check or getting any “government assistance.” As Hochschild sums up, “Getting little or nothing from the federal government was an oft-expressed source of honor.” Views about work and government are linked: the suspicion of government assistance comes in part from a belief that those who rely on it are not working their fair share, and thus evading a fundamental social duty. The same subject cited by Hochschild thus reserves her harshest criticism for “people who take government money and don’t work… That’s not right. They should do something to help” (157). These beliefs persist in spite of the fact that the individuals who hold them are most likely to be eligible for government support programs, given their vulnerability to structural change. As Kolben (Reference Kolben2021) observes: “the group that is perhaps most skeptical of government supports and programs is the group that is also most directly affected by trade- and technology-induced job displacement” (693).Footnote 17

Although these studies make few general claims across space, time, or industry when describing their subjects’ deep identification with their work, they often attribute it to a blue collar, conservative, small town setting. Indeed, subjects often report that their work ethic and pride in “hard work” is what distinguishes them from elites—especially liberal elites, who they claim lack an equivalent sense of dignity, duty, and self-sacrifice.Footnote 18

It is worth emphasizing that these two theoretical approaches represent ideal types. In the first case, the view of work as a means is rarely explicitly defended by economists, and functions more as a background assumption in economic modelling. A growing number of economists also recognize that work does have intrinsic value beyond its monetary reward.Footnote 19 In the second case, sociologists and social psychologists are increasingly open to the ways in which wages may themselves affect intrinsic motivation and social status (Olafsen et al. Reference Olafsen, Halvari, Forest and Deci2015). Yet if anything, much of this work shows the limits of such efforts, with most evidence showing that motivation and work satisfaction are only weakly responsive to monetary compensation, which can sometimes have deleterious effects (Abd-El-Fattah Reference Abd-El-Fattah2010). In this way, the distinction between work as a means, and work as an end, remains a useful one for generating testable expectations. The question we take up in the empirics is, which approach better reflects the views of actual workers? And how does this affect individual perceptions of wage buyout programs?

Attitudes to Work in the Face of Structural Threats

Since wage buyouts are proposed when the externalities of an industry outweigh its private benefits to workers, a relevant question is how workers respond to such pressures on their industry. The Dutch nitrogen directive mentioned earlier, for instance, is the result of a longstanding EU campaign. Does such external pressure make workers more—or less—open to wage buyouts over time? Here, too, the literature is split. One set of studies suggests that external threats lead to entrenchment: workers identify more strongly with their industry in ways that might make them more resistant to transitioning away from it (Strangleman Reference Strangleman2001; Lobao and Meyer Reference Lobao and Meyer2001). This echoes studies in social psychology looking at racial identity and discrimination, which have found that perceived threats to the group can lead to heightened group identification (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Reference Branscombe, Schmitt and Harvey1999; Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje Reference Ellemers, Spears and Doosje2002). By the same logic, we might expect that Dutch dairy farmers, coal workers facing energy transition, or U.S. steel workers exposed to foreign competition would identify more strongly with their industry because they perceive it to be under attack.

A competing set of studies leads to the opposite expectation. Threats to job security, in particular, have been shown to reduce industry attachment through an individual-level coping mechanism (Selenko, Mäkikangas, and Stride Reference Selenko, Mäkikangas and Stride2017; Piccoli et al. Reference Piccoli, Callea, Urbini, Chirumbolo, Ingusci and De Witte2017). If so, then U.S. steel workers may read the proverbial “writing on the wall,” foresee the likelihood of job loss, reduce their identification with the industry by anticipation, and thus become more open to exit schemes. Similarly, threats to an industry could also decrease the status associated with it, and thus motivate identity displacement as a status management strategy (Shayo Reference Shayo2009).

Whether external threats lead to stronger or weaker identification with work has implications for how resistance to wage buyouts might evolve over time. Pressure to reduce the size of industries associated with negative externalities is likely to rise with growing awareness of those externalities. Under the first expectation, we should expect greater hostility to wage buyouts as external pressure mounts. Under the second, we would expect that resistance would decrease over time, as workers anticipate labor market shifts, and grow more open to exiting. In the empirical analysis that follows, we attempt to distinguish between these.

The Politics of Wage Buyouts

In the wake of deindustrialization in Western economies over the last several decades, the debate over the value and meaning of work has taken on renewed political valence. In particular, the social fallout from the decline of manufacturing across developed economies has put the feelings emphasized by the sociological treatment of work on vivid display. As advanced economies have progressively shifted to service sectors, even those workers who have been made economically “whole,” either through government assistance or by finding work in new sectors, speak of a prevalent sense of loss. As focus groups run by the Pew Research Center in 2020 in both the United States and the United Kingdom suggest, when “new job creation supplant[s] traditional work”, it “lead[s] to feelings of alienation and loss.”Footnote 20

A number of studies show how right-wing parties have been especially adept at exploiting this sense of loss (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Walter Reference Walter2021), fostering what has been described as an “economics of nostalgia.”Footnote 21 This bears directly on political positions taken towards wage buyouts. The narrative of a government accelerating the labor shift from traditional, historical industries—like farming, fishing, mining, and manufacturing—to address more abstract welfare objectives around biodiversity and decarbonization has served as fodder for right-wing parties. These political entrepreneurs have promised the very opposite of adjustment, by vowing to bring back jobs in these same sectors, in spite of powerful structural forces that make this unlikely (Baccini and Weymouth Reference Baccini and Weymouth2021).

In keeping with this political messaging strategy, U.S. president Donald Trump singled out the Dutch wage buyout at as an instance of a technocratic government interfering with citizens’ economic freedom, declaring the Dutch farmers are “courageously resisting the climate tyranny of the Dutch government.”Footnote 22 The Polish far-right Law and Justice party has also vowed to support the position of the Dutch farmers against the nitrogen directive in the EU,Footnote 23 as has Marine Le Pen, the French leader of the far-right Front National party, who publicly came out against the “expropriation” of Dutch workers.Footnote 24 These populist leaders have taken up the narrative that work is an end in itself: they have capitalized on the sense among working class voters that the values they hold dear—among them an ethic of hard work, self-sacrifice, and contribution to one’s local community—are being debased, in favor of cosmopolitan ideals held by liberal elites.

It follows that the view of work as a source of significant intrinsic benefits, combined with the incentives of populist political entrepreneurs, does not bode well for wage buyout schemes. The question is, to what extent do wage buyouts represent an opportunity for political entrepreneurs to capitalize on the gap between governments’ technocratic treatment of work (closer to the economic ideal-type approach) and prevailing public attitudes towards work? And relatedly, are these attitudes to work a fundamentally partisan issue? Is the fact that political criticisms of wage buyouts come from the political right best seen as an attack on technocratic government programs, or a reflection of underlying beliefs about (non)work? We tackle these questions in the analysis.

Evaluating Attitudes Towards Work and Non-Work

We use the theoretical framework outlined earlier to generate a set of empirical expectations over attitudes towards work and non-work. To test these expectations, we fielded three pre-registered surveys on U.S. adult samples, amounting to a total of over 7,500 respondents. The first sample (n=2450) respondents was recruited through the survey firm Respondi in January 2022; the second sample (n=2092) was recruited through Prolific in August 2022; the third sample (n=3145) was recruited through Bilendi in May 2023. In each case, samples were selected to meet population quotas by age, gender, census region, and education. The first sample was limited to currently employed individuals; the second and third samples also included unemployed respondents (we thus add employment status among the covariates in the analysis). Tables A2, A3, and A4 in the online appendix show demographic breakdown and summary statistics for each sample (Pelc Reference Pelc2025).

We focus on the United States for several reasons. First, much of the recent sociological literature on work has looked to specific sectors in the U.S. labor force. Secondly, the United States remains the standard-bearer of the Protestant Ethic and its modern secularized equivalent, as well as the American Dream ethos of success through hard work (Ballard-Rosa, Goldstein, and Rudra Reference Ballard-Rosa, Goldstein and Rudra2024). Such an emphasis on prosperity as a means to social standing could lead individuals to view work in a more instrumental fashion; on the other hand, the original Calvinist view of work as a “calling” might lead to the opposite. Beliefs about work are thus central to the American experience. Does this make the United States an outlier in terms of beliefs about work? While there are no data on people’s attitudes to wage buyouts specifically, there do exist large cross-national surveys probing attitudes to work more generally. In particular, two questions from the most recent wave of the World Values Survey (2017–2022) provide an indication of where the United States falls globally. The first asks about the importance respondents assign to work and leisure, on an independent scale of 1–4. Figure A1 in the online appendix graphs responses by country, looking at OECD members for greater comparability. Figure A2 looks at a second relevant WVS survey question, which elicited respondents’ level of agreement with the claim, “Work is a duty towards society,” on a scale of 1–5. In both cases, the United States falls almost exactly in the middle of the fifteen OECD countries included in the WVS sample. In fact, it happens to be the country that weighs work and leisure most evenly across the OECD subsample.

The issue of work is thus salient in the United States’ conception of itself, yet the country appears close to the average in terms of the importance that individuals assign to work. Nonetheless, U.S. policy does in fact set it apart from other OECD countries: it typically ranks lower in terms of direct welfare transfers,Footnote 25 and features greater labor market flexibility, with more liberal firing policies and fewer regulations on temporary work contracts.Footnote 26 As a result, a natural extension of this study would compare attitudes towards wage buyouts across different countries.

Baseline Attitudes Towards Wage Buyouts

We begin by offering some descriptive statistics on attitudes towards wage buyouts. Our first study, conducted in early January 2022, asked all currently employed respondents the following question:

How willing would you be to stop working at your current job for the foreseeable future in exchange for a monthly check [from your former employer / government] equivalent to your full current salary? [1: Not willing at all — Very willing: 10]

where the bracketed text indicates the two randomized treatment arms. A control group was given no additional information about the source of compensation.

Before presenting the treatment effects, we focus on the control group’s responses to offer a baseline of overall attitudes towards the scheme, setting aside feelings towards government assistance for now. Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses. Most people appear at least somewhat ambivalent about giving up their work in exchange of a full paycheck. Just under 32% of respondents are fully willing to accept the compensation scheme, while over 8% are entirely unwilling, with the remainder of the sample distributed in between. One quarter of respondents would be more likely to refuse than to accept the scheme; 69% of respondents would be more likely to accept than to refuse it.Footnote 27 In the next section, we look at how the source of compensation affects these feelings.

Figure 1 Attitudes towards wage buyouts (baseline)

“How willing would you be to stop working at your current job for the foreseeable future in exchange for a monthly check equivalent to your full current salary?”

Figure 2 Attitudes towards wage buyouts

Another informative descriptive is the variation in attitudes across industries. Figure A3 in the appendix orders all respondents by their NAICS 2-digit industries, from most open to least open to wage buyouts. At the top of the list is mining, with manufacturing not far behind. Arts, entertainment, and recreation, and Information industries are at the bottom—as are Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting, from which draw the motivating example from the start of the article. Yet beyond this ordering, one takeaway from figure A3 is that overall, respondents’ industry provides relatively little traction on individual attitudes: the difference between the most favorable and least favorable industry is barely statistically significant at conventional levels. As per the rest of the analysis, most variation appears at the individual rather than the industry level.

Treatment 1: Varying the Source of Compensation

In the survey question cited earlier, two treatment groups were informed that compensation under the wage replacement scheme would be coming either from the government or their former employer. The experiment’s purpose is twofold. First, we want to gauge how much of the resistance to wage buyouts comes from resistance to all forms of government assistance. Numerous studies attest to the way in which people who might be eligible for government benefits often take pride in not relying on these benefits. As Williams (Reference Williams2019) writes of her working class subjects’ attitudes towards government assistance, “They saw it as an affront to their dignity. I heard so often things like, ‘I don’t want a government handout; I can do this on my own.’ So even when they were aware of the government benefits they were entitled to, they did not accept them” (22).

Secondly, this treatment acts as a test of prevalent expectations around how closely individuals identify with their workplace, and to what extent this identification might sway their attitudes towards non-work. A classic definition of social identity describes it as “that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership in a social group together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981, 255). This value attributed to shared membership is often attributed to the workplace.

Political leaders often seek to capitalize on this shared identity: visiting factories and workplaces is a standard feature of electoral campaigns. In a representative instance, President Trump visited a Whirlpool plant in Clyde, Ohio, August 2020, to praise its workers as “hardworking patriots.”Footnote 28 He called one of these workers to the stage, who in turn declared, “I work with 3,500 proud individuals. Together … we bleed Whirlpool blue.”Footnote 29 This type of strong identification to an employer, of a type more commonly associated with national or religious identities, is what the sociological and social psychological literature highlights as characteristic of blue-collar workers, especially in rural areas, and especially in “single-industry towns” where one employer comes to play a large role in a community’s conception of itself. Work becomes a source of social status and dignity. The expectation of the first experimental treatment is that insofar as this workplace identity exists, then the fact that compensation for non-work would continue to come from the former employer should lessen the identity loss that results from being taken out of the labor force might represent. If so, we would expect that all else equal, a wage buyout scheme where compensation was tied to the former employer would draw greater support than the control.

This first treatment also reflects real-world policy considerations. A similar choice might come up whenever a sharp reduction of the workforce in a sector would bring both private benefits to the industry, and public benefits to society. To take the example of technological change: one scenario foresees self-driving truck technology becoming sufficiently reliable to replace the approximately 294,000 workers who earn above-average wages from long-distance trucking. Compared to human drivers, self-driving trucks are thought to be safer, faster (since they require no sleep), and require less fuel, since they allow for fleets of trucks drafting each other to reduce wind resistance (Viscelli, Reference Viscelli2018). Yet trucker unions oppose the adoption of such technology to protect the jobs at stake. If governments step in to capture the public benefits of technological adoption, they face a choice as to whether to channel transitional assistance through trucking companies—in the form of furloughs or early retirement—or through standalone government programs. Does this design choice matter?

In addition to estimates for the two treatment arms, we also control for a number of individual traits. The first of these is political ideology, scored from left to right on a 0–10 scale, and political partisanship, coded as Democrat and Republican, with the reference category of independents and “other.” Given the politicization of wage buyouts described earlier, it is difficult to distinguish the extent to which attitudes towards work are inherently associated with partisan values, as opposed to beliefs transmitted top-down by partisan leaders. Most likely, it is because of some latent receptiveness to these arguments that populist leaders on the political right have been capitalizing on a narrative of “hard-working patriots” who work in the “real economy.”Footnote 30 We also add controls for education, as a proxy for skill level; income; gender, given an emphasis in the ethnographic literature over men’s greater identification with work (Hodson et al. Reference Hodson2001); race, given the focus on the occupational identity among white workers (Lamont Reference Lamont2002; Williams Reference Williams2019); and age, which may be a consideration given older workers’ greater apprehension around shifting sectors. Finally, since the survey was conducted in January 2022, when COVID-19 was still a concern, we ask all respondents the extent to which COVID-19 has impacted their lives. We also test for a preregistered expectation that even controlling for income (with which the impact of COVID-19 is negatively related), respondents who bore a greater toll as a result of the pandemic should be more open to wage buyouts. This variable also proxies for individuals who received government support through the U.S. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), which provided direct financial relief to individuals affected by COVID-19, which may have normalized the idea of receiving checks from the government (Crabtree and Wehde Reference Crabtree and Wehde2023).

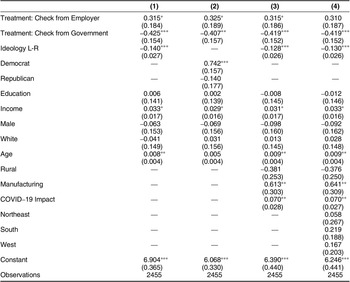

As seen in the coefficient plot in figure 2, both treatment effects prove significant. Being told that the check is coming from government significantly reduces favorability towards the scheme, with an average of 6.39 on the 0-10 scale. Being told that the check is coming from a former employer significantly increases approval, with an average approval of 7.07. That is, the Government Check treatment shows a greater downward effect than the Former Employer treatment, but both are significant at conventional levels. The difference between both treatments amounts to a large substantive effect, equivalent to that of varying respondents’ ideology from the sample mean (5) to its furthest extreme (10). Given how modest the treatment is in the survey, we interpret this across-respondent variation as an especially strong treatment effect. In terms of both statistical significance and magnitude, the government treatment appears to increase resistance more than the employer treatment decreases it.

As expected, ideology is significantly related to attitudes towards wage buyouts. Conservatives are far less favorable to the scheme than liberals, and Republicans are far less favorable than Democrats. Yet interestingly, the magnitude of the treatment effects are not statistically different between the two groups. Republicans are thus no more responsive to the Government Check treatment than Democrats. In the third study, we dig into the components of the partisanship effect.

As for other demographic variables, the striking takeaway is how little they seem to matter. Despite much emphasis in the literature on the importance of race, gender, and skill level, none of these prove significantly related to attitudes towards wage buyouts. This may seem especially surprising for gender, yet it is in keeping with the ambivalent relationship between gender and beliefs around work in large values surveys. In the most recent World Values Survey (wave 7), women in the United States assign significantly higher importance to work than men, while the reverse is true, on average, for other OECD countries. In the same way, rural settings (which comprise country villages, farms, and rural homes) do not appear to be more averse to wage buyouts than urban settings (which comprise large cities, towns, and suburbs): Rural is significant on its own, but not once ideology is controlled for. Just as interestingly, manufacturing workers are, if anything, more inclined to accept wage buyouts. This is especially relevant given the importance of targeted labor adjustment schemes designed to deal with the labor decline in manufacturing and how their mixed success has often been attributed to the strong occupational identities of manufacturing workers (Kolben Reference Kolben2021). Similarly, no geographic region shows a distinct set of attitudes towards wage buyouts. If anything, respondents from the South, who comprise 38% of the sample, are slightly more open to wage buyouts, but the relationship does not approach statistical significance.

We check for heterogeneous treatment effects across all demographic categories by testing whether these cleavages matter for respondents’ receptivity to the treatments. Here, too, there is little effect. The one exception seems to be low-income respondents, who tend to view compensation coming from the government slightly more favorably than high-income individuals, all else equal.

Vulnerability to structural forces: Automation and offshoring. There is no adequate means of objectively assessing the likelihood that a given occupation might be targeted by wage buyout schemes. Ideally, such a variable would capture all negative externalities generated by some occupations over others, and their relative salience across countries. Dairy farming would rank high on such a measure, especially in the Netherlands, given the relative size of the sector and its proximity to the country’s nature reserves (Stokstad, Reference Stokstad2019). As an alternative, we consider two other structural forces where we have better measures: automation and offshoring. Both automation and offshoring give rise to the same competing expectations, outlined above in the earlier theory section, over how structural threats to an industry may lead to either further entrenchment, or a weakening of group identity. In all these cases, the question is, as the “writing on the wall” becomes more legible, do workers identify more strongly with their work, and thus grow more resistant to leaving it, or the opposite? Testing for the effect of exposure to automation and offshoring on attitudes towards non(work) is thus a way of assessing the explanatory power of these two competing theories.

We assign Routine Task Intensity (RTI) and Offshorability scores calculated by Goos, Manning, and Salomons (Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014) to each respondent, using three-digit ISCO-08 occupation codes. This offers an objective measure of workers’ exposure to these two structural forces.Footnote

31 Because we are not able to match all occupations perfectly, the sample drops from 2,450 to 2,198 respondents. Figure A4 in the appendix shows the breakdown of these two measures in the sample by industry, and the high correlation between the two (

![]() $ r $

=0.72). For this last reason, we include them separately in our estimations. We then also elicit a corresponding subjective measure, asking respondents to estimate how likely they are to lose their job due to automation and to offshoring. Are these workers more or less resistant to wage buyouts?

$ r $

=0.72). For this last reason, we include them separately in our estimations. We then also elicit a corresponding subjective measure, asking respondents to estimate how likely they are to lose their job due to automation and to offshoring. Are these workers more or less resistant to wage buyouts?

The next indicator of interest in this analysis is a measure of subjective social standing. Studies seeking to explain the surge of populism and pushback against globalization and democracy in developed countries have begun looking to social standing as a notion that brings together economic and cultural explanations for the backlash (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2020). These studies rely on the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status, which was first developed by Adler et al. (Reference Adler, Boyce, Chesney, Cohen, Folkman, Kahn and Syme1994) and which we adopt here. Respondents are presented with a picture of a ladder with 10 rungs, which they are told represents the standing of all people in the United States, and they are asked to place themselves on the ladder (refer to the online appendix for the full question).Footnote 32

Finally, we also add an indicator of whether the respondent belongs to a trade union. We remain agnostic about the relationship, since here too, theory offers differing expectations: labor unions tend to be opposed to wage buyout schemes, which naturally reduce the size of their membership. The largest Dutch farmers’ trade association, for instance, is staunchly opposed to the nitrogen directive. Union membership may itself also breed greater identification with one’s job, and thus a greater value attached to non-pecuniary aspects of work. On the other hand, unions traditionally push for decreased working hours, and longer break time and vacation pay. The fact that the cessation of work through strikes has long been unions’ tool of last resort may also normalize the notion of non-work.

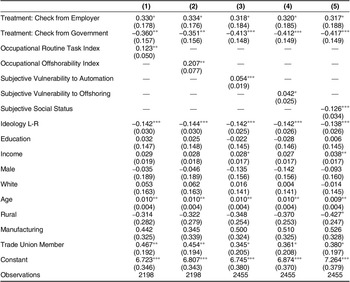

The findings are shown in table 2. The effect of vulnerability to structural forces is strong and consistent. Whether it is exposure to automation or offshoring, and whether it is measured objectively or subjectively, respondents who are more prone to job losses due to these forces are also more favorable to wage buyout schemes. Social standing proves equally significant. Individuals who report higher subjective social standing are significantly less likely to accept a wage buyout scheme. Taken together, these five variables tell a coherent story. Exposure to structural forces that make individuals more likely to be targeted by wage buyout schemes are associated with more, not less, openness to these schemes. Social standing, which is negatively correlated with all four indicators of economic precarity, is in turn inversely related to the same attitudes towards non-work.

Trade union members appears consistently more open to wage buyouts, even after controlling for male and manufacturing workers, both of which are positively correlated with union membership. One interpretation is that the common negotiation objectives of unions may normalize the notion of non-work, and strip it of its negative associations.

Variation in the strength of occupational identity. To further get at underlying beliefs about work, we separately elicit respondents’ level of identification with their jobs, by asking them to rank the importance of their job as a personal trait, in comparison to other personal identifying traits: religion, family, origin, race, hobbies, political beliefs, and other.Footnote 33 We reverse the scale, so that higher rankings indicate a stronger occupational identity, and we regress this occupational identity variable on the same set of demographic variables as earlier. This survey design is in keeping with identities being plural (made up of a number of different traits), and relative (emphasis on one trait may come at the expense of others). It is also consistent with identity as the a conception of the self that individuals construct and present to others.

Table 3 shows the results. The two most consistent drivers associated with occupational identity are education and race: as per the implications of Lamont (Reference Lamont2002) and Williams (Reference Williams2019), white respondents show greater identification with their work. The same is true for high-skilled respondents. Income shows a consistent positive relation. More conservative political ideology is negatively related to occupational identity, yet this does not translate into significant effects for partisanship: while Democrats (Republicans) are associated with slightly stronger (weaker) occupational identity, neither is statistically significant.Footnote 34 As before, the null findings offer interesting takeaways: as opposed to claims in some ethnographic accounts of work, men, and those living in rural areas, do not appear to identify more strongly with their work compared to other personal traits. Manufacturing workers, if anything, show a negative relation, though it does not cross the significance threshold. Recall that the sample is restricted to currently employed respondents; students and retired individuals would likely identify differently with work, but they are purposefully omitted from the sample.

Figure 3 Attitudes Towards Wage Buyouts, Full vs. Partial

“Imagine a new government program that would continue paying your current salary and health insurance, but you have to [treatment] to claim these benefits. How likely would you be to enroll in this program?”

In sum, race and education appear to affect the strength of occupational identity, yet as shown in table 1, these effects do not seem to translate into greater resistance to wage buyout programs—even when such programs are explicitly government-backed. On the other hand, vulnerability to structural forces like automation and offshoring decreases the extent to which individuals’ identify with their work. The implication is that as awareness of specific industries’ negative externalities grows, and regulatory pressure rises in response, the effect may not be entrenchment among workers, but its opposite: a displacement of self-identification with work, and potential greater openness to wage buyout schemes.

Table 1 Attitudes towards wage buyouts

Note: *

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. The control group receives no information about the compensation’s provenance. Comparison category for region is “East”.

$ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. The control group receives no information about the compensation’s provenance. Comparison category for region is “East”.

Treatment 2: Partial versus Full Redundancy

Our second study relies on a different sample of 2092 respondents. It relies on a similar basic question to the first, but tweaks its formulation. First, all respondents are explicitly told that the scheme is a government program; second, and in response to comments to the first study, we now explicitly mention that participants retain their health insurance under the scheme. Since health insurance in the United States is most often associated with the employer, this is meant to ensure that a concern over insurance does not drive the results. We then use a simple experiment to test another aspect of program design. We compare respondents’ attitudes towards a proposed reduction of half of one’s working hours versus full redundancy. The question reads:

Imagine a new government program that would continue paying your current salary and health insurance, but you have to [stop working / work half the hours you work currently] to claim these benefits.

Insofar as workers are simply trying to maximize the ratio of compensation to working hours, one would expect that a maximum reduction of working hours, keeping compensation fixed, would be viewed most favorably. But if respondents attach importance to the social status that comes from holding a job, the conception of themselves as a working individual, and the sense of belonging they draw from workplace, then they might be willing to forfeit an additional reduction of working hours to preserve these values.

This second treatment also reflects real-world policy choices. Governments face a choice when seeking to reduce the size of a sector with negative externalities, as in the case of dairy farming in the Netherlands. They can target the extensive or the intensive margin. That is, they can either reduce each individual’s work by 1/x, or seek to remove 1/x of the workforce from the sector. Insofar as both reduce total production by the same level, these options may be equivalent from an economic standpoint. The question is whether these options would be viewed differently by workers.

The results, shown in figure 3, are striking. Overall, respondents are favorable to the full wage buyout scheme at similar levels to Study 1, suggesting that concerns over health insurance did not significantly affect the results in Study 1. Yet what is remarkable is the difference between the two treatment conditions: respondents are significantly more open to having their working hours cut by half, than to cease work entirely. Specifically, the average level of approval for decreasing working hours by half is 8.17 on the 0–10 scale, while the average approval for ceasing work entirely is 6.86. Recall that this represents variation across respondents, who only receive one or the other treatment. In descriptive terms, the “stop working entirely” condition is most similar to the “government check” condition in Study 1, and yields a similar level of approval: 6.86 compared to 6.39 in Study 1. In sum, these results lean strongly in favor of policy approaches to wage buyouts that focus on the intensive rather than the extensive margin, reducing working hours rather than removing individuals from their work environments entirely.

It is worth comparing the role of education and income across the two studies. In Study 1, education has no consistent effect, while income is slightly positively related with openness to wage buyouts, though also inconsistently so. Yet both are positively correlated with personal identification with work. In Study 2, education is again insignificant across the board, while income shows a slight negative relationship. In sum, the net effects of these two key variables on attitudes towards work and non-work remain ambiguous in ways that likely speak to conflicting underlying mechanisms. Yet the findings do allow us to dispel the notion that low-skill working class individuals who are more likely to hold physically demanding occupations develop a uniquely strong work identity in ways that make them value their work more highly.

Treatment 3: Government Program versus Lottery Windfall

In a third study, we worked with the market research firm Bilendi to recruit a third sample of adult Americans (n = 3,199) demographically representative by party identity, age, and gender. This time, we compared attitudes to a wage buyout program versus an equivalent lottery windfall. The main objective was to determine what part of the attitudes towards wage buyouts was driven by attitudes towards government programs or attitudes towards (non)work. All respondents received the following two questions, in randomized order:

[Lottery windfall] Imagine you have won the lottery. The amount of the prize is enough to maintain your exact current income, adjusted for inflation, for the rest of your life. Would you decide to stop working your current job?

[Government program] Imagine a government program that would pay you a monthly amount equivalent to your current income, adjusted for inflation, for the rest of your life. The government program requires you to stop working your current job. Would you agree to join this program?

Specifically, following on the apparent importance of partisanship for wage buyouts in tables 1 and 2, we were interested in how partisanship would be associated differently with responses to the two questions. If the observed importance of partisanship is mainly a response to the role of government in wage buyouts, then we should expect a large gap in support for the two proposals, a large partisan divide in support of the government scheme, and a comparatively smaller partisan divide in support for the lottery windfall scheme. If, in turn, partisanship functions primarily by determining attitudes towards (non)work, then we should expect a small partisan gap between the two proposals, and consistently large partisan gaps for each proposal. In contrast to treatments 1 and 2, the two options in the third study also specified the replacement income would be offered indefinitely (“for the rest of your life”), to ensure that respondents did not hold inconsistent beliefs about the length of the program. Finally, in addition to the demographic traits in the first two treatments, the third study also queried respondents about their religious affiliation, given the long-established relationship between Protestantism, especially, and attitudes to work.

Table 2 Economic precarity and wage buyouts

Note: *

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. The control group receives no information about the compensation’s provenance.

$ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. The control group receives no information about the compensation’s provenance.

Table 3 Drivers of occupational identity

Note: *

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. DV is ranking of “job” in response to the question, “In describing yourself, which of these traits would you view as most important?” Refer to the online appendix for the detailed questionnaire.

$ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. DV is ranking of “job” in response to the question, “In describing yourself, which of these traits would you view as most important?” Refer to the online appendix for the detailed questionnaire.

The results shown in table 4 prove informative. The first thing to note is that the order of the treatment appears to make little difference to responses to the lottery windfall versus the government program. That is, being presented with the lottery windfall option first did not significantly “normalize” approval of the government program. Conversely, being presented with the government option first only mildly “corrupted” respondents’ willingness not to cease work in the wake of a lottery windfall. The results also allow us to better disentangle the effects of partisanship: as in previous tests, Republicans are significantly more wary of a government wage buyout; yet they appear no less open to ceasing work following a lottery windfall. By contrast, Protestantism is consistently associated with reluctance to cease work under both schemes. Protestants are also significantly more negatively disposed to the government scheme than to the lottery windfall, yet perhaps most striking is that Protestant religious affiliation appears as the strongest predictor of the decision to (not) cease work following a lottery windfall. Catholicism, by comparison, sees strictly no effect, suggesting this attachment to work is not driven by broad Christian values, but by specifically denominational ones. This is an interesting finding in its own right, but it also speaks to how attitudes to (non)work are culturally-specific, and may thus vary by country. And while Republicans are associated with Protestantism,Footnote 35 even in a bivariate regression, Republicans appear no less open to ceasing work following a lottery windfall.

Table 4 Response to government schemes versus lottery windfall

Note: *

![]() $ p<0.10 $

, *

$ p<0.10 $

, *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. DV in (1) and (2) is support for the two different options; (3) estimates the individual difference in support of (1–2).

$ p<0.01 $

. Robust standard errors clustered by state reported in parentheses. DV in (1) and (2) is support for the two different options; (3) estimates the individual difference in support of (1–2).

Taken together, these three studies contribute to our understanding of individual attitudes towards work and non-work. Yet there remains much to be done in this direction. In particular, the finding that those who are more prone to structural forces are also more open to wage buyout programs is consistent with different potential mechanisms. Future research could seek to disentangle these, by examining whether it is greater economic precarity that leads to lower levels of identification with work, or whether this comes down to the types of occupations that happen to be more exposed to structural forces like offshoring and automation. This distinction will become especially relevant when looking at high-skill occupations—which we find are associated with significantly stronger occupational identities—that may rapidly become replaceable by large language models and other advances in A.I. In this respect, it is worth noting that the third study, the only one of the three studies run after the popularization of LLMs like Open AI’s GPT model, is also where college educated respondents appear more open to a government wage buyout. This may be further suggestive evidence that as pressure on an industry grows—be it market pressure, regulatory pressure, or technological pressure—workers may grow more, rather than less open to exiting the workforce.

Conclusion

Upton Sinclair famously claimed that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” As this article demonstrates, it may be all the more difficult if what is at stake is not merely a salary, but the sense of identity and belonging that individuals derive from their work. Governments are now increasingly able to replace people’s salaries to get them to “understand” the need for some policy reform, be it in the name of environmental protection, decarbonization, or greater economic efficiency. Such worker buyouts sometimes succeed in accelerating beneficial social change, yet they can also result in widespread protests. What explains the attitudes of democratic audiences to these wage replacement schemes?

This question has become highly politicized. Right-wing populist leaders, in particular, are taking aim at measures which they claim are imposed by technocratic elites who fail to appreciate the value of a job to hard-working individuals. This political messaging is most often targeted towards the male, rural, low-skill voters who have already borne the brunt of deindustrialization in developed economies over the past three decades, and who have been promised various kinds of welfare schemes or transition adjustment programs to cope with job loss.

The theoretical framework outlines two competing sets of expectations over attitudes towards work and non-work. The first, which has largely informed policy until now, assumes that individuals primarily value their job for the associated income. The implication is that people who are forced out of their jobs can be made “whole” through monetary compensation. A competing view claims instead that work has inherent social value; it is a source of personal pride and recognition, a means by which individuals build their identity. This perspective has arguably gained ground among policymakers forced to deal with the social upheaval caused by deindustrialization and the labor dislocation associated with it.

This article takes a first step in assessing the explanatory weight of these two views. The result is a nuanced picture of individual attitudes towards work and non-work. The first finding shows just how reluctant workers are to be “freed” from the burden of work. Three survey studies conducted on a total of over 7,500 U.S. respondents suggest that many workers are ambivalent about giving up their work, even if they could continue drawing their full salary. So much so, that a majority would choose a program that cuts half their working hours over one that cuts them entirely, even if their compensation remained the same. This insight is in line with the view that work is a source of value that goes beyond the income it procures, and it constitutes an important correction to the mainstream economic view. It implies that wage replacement, by itself, may be insufficient to convince individuals of the benefits of a policy reform that will make their work redundant.

Yet this baseline attitude to wage buyouts conceals considerable heterogeneity. First, while partisanship is associated with a strong aversion to wage buyouts, this seems driven more by attitudes against government programs, and less by attitudes to (non)work per se, suggesting that careful program design could help overcome the partisan divide over wage buyouts. Creating such programs through employers, as per Study 1, may be one means of doing so. The analysis’ other findings partly clash with the sociological literature on work. Much of this scholarship examines low-income, male, working-class occupations. Perhaps owing to this focus, these studies highlight, first, the singular value assigned to hard work for its own sake in these settings; and second, the pride that working class individuals take in not relying on government assistance. Yet the findings show that occupations that feature repetitive tasks, those that are more prone to automation, as well as occupations that can more easily be outsourced to foreign labor, are associated with lower occupational identity. Individuals in these occupations are also, accordingly, more open to being removed from the labor market in exchange of government compensation. In correcting for the orthodox economic view of jobs-as-income, the risk is that scholars and the media may both fall prone to a romanticization of the economic heartland, portraying blue collar and manufacturing workers as unresponsive to economic incentives, owing to an idiosyncratic attachment to work for work’s sake.

As it happens, the person quoted in the protests against the Dutch nitrogen directive, spurning “a bag of money from the government,” was not a low-skilled worker, but a veterinarian, whose livelihood was dependent on the dairy sector.Footnote 36 The evidence suggests that on average, it is such high-skill individuals who exhibit the highest occupational identity, and may thus be most resistant to government programs that displace workers in the name of socially beneficial reforms. In this way, the findings speak to the scale of the challenge governments may face if advances in artificial intelligence deliver on their promise. The “world without work” that some economists foresee for advanced economies (Susskind Reference Susskind2020) has already produced considerable social dislocation in blue collar manufacturing sectors; recent advances in large language models and other AI tools suggest that the same dislocation may await large sectors of the knowledge economy. The findings imply that these effects may grow increasingly disruptive as they begin targeting white collar workers who identify more highly with their work, and are more resistant to giving it up in exchange of continued pay.

The cost people perceive from being removed from the labor market is not reducible to lost income: it includes inherent personal and social benefits that individuals derive from their work. If such attitudes remain unchanged, then even highly generous welfare schemes may fail to appease workers’ resistance to reforms—resulting from either structural forces or regulatory measures—that make their work redundant. While those studying governments’ responses to future labor dislocation tend to focus on the fiscal constraints on such interventions, this article shows that an understanding of people’s attitudes towards work and non-work proves equally important.

Data replication

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FNPBKD

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Vincent Arel-Bundock, Kathryn Harrison, Sam Rowan, Claudia Zwar, and the participants of the 2024 EPG Workshop for useful comments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592724002573.