During the German refugee crisis, Willy Wimmer, member of the German Christian Democratic Party, predicted that “this is the end of the Chancellorship of Angela Merkel.” Russian Channel RT, operating in German, publicized his views, alongside other articles, declaring that the Chancellor is an “autocratic” leader who turned her own party into a political graveyard, and that “Merkel is breaking German law and endangering the country” with her decisions on refugees. Chancellor Merkel had been a staunch supporter of post-Crimea sanctions against the Kremlin: RT coverage seemed like a payback. The use of directed political communication by foreign actors to sway the politics of a country, especially close to elections, appears to be easier and more prevalent than ever. In this article, we study the general phenomenon and we look more in depth at the case of Germany during the “refugee invasion,” to borrow a term from RT.Footnote 1

We identify the type of political communication produced by a particular class of regimes, delineate the likely targeted beneficiaries, and demonstrate its occurrence in an important case, the refugee crisis in Germany. The refugee crisis was exploited by the right-wing populist, partly extremist, and even anti-systemic Alternative for Germany (AfD) party. The refugee issue distinguished AfD’s political communication from that of Germany’s mainstream political parties, who were more positive on the new arrivals than the AfD. We show the latter with an analysis of party communications. We also show—by analyzing nearly one million news articles—that Kremlin-directed outlets operating in German were markedly more negative on the issue of refugees than German media, and exhibited a greater conspiratorial bias. Among others, these outlets focus on portraying German chancellor Merkel negatively, linking failures in the refugee crises with her directly, splitting the governing parties by inviting intra-party critics to interviews and aiming to keep the refugee issue on the agenda for years after the immediate crisis.Footnote 2 Especially after the federal election of 2017, these outlets emphasize the AfD being the winner of the election, heavily criticizing the “mainstream” parties and chancellor Merkel.Footnote 3 Thus, Kremlin-sponsored media provided what AfD operatives may have found useful—a news forum publishing appropriately slanted migrant stories, to refer to in political discussions. We find evidence that Kremlin-supplied coverage spiked, compared to domestic outlets, around the national elections that also resulted in AfD’s most significant political breakthrough. The success of the AfD benefited the political agenda of the intervener, by making coalition-building among established parties more difficult. The anti-refugee message more broadly exacerbated internal divisions in the ruling parties and may have dissuaded voters from turning out.

In foreign election interventions, often what is most difficult to show is that attempts to sway the election are, in fact, being made (Brutger, Chaudoin, and Kagan Reference Brutger, Chaudoin and Kagan2021). Senders of interventions often deny or fail to acknowledge that their actions can be construed as that: China manipulated retaliatory tariffs in a manner that hurt the Republican Party (Kim and Margalit Reference Kim and Margalit2021). Foreign governments can argue that the discourse promoted through propaganda efforts has no obvious political beneficiary, and in any event, it is not intended as election intervention. By obtaining a large corpus of different news media materials over time—and political parties’ communications—we show that foreign communication was systematically different from domestic media, that it was aligned politically (thematically) with a specific party, and that coverage spiked close to elections, again relative to domestic news channels. In tracing the existence and mechanism of intervention, our contribution is to provide a set of tools—conceptual and methodological—to identify how directed political communication turns into an election intervention. Thus, we take a step that is a necessary condition to study the wider prevalence of the phenomenon of political communication as election intervention.

The methodology we have employed in this work is borrowed from the field of computer sciences, it relies on tools developed in the field of natural language processing (NLP) and their adaptation to the political science domain. This interdisciplinary area of research allows modeling of complex phenomena, such as the one discussed in this paper. It helps researchers process large-scale amounts of textual data and to employ automated methods to analyze those massive amounts of text.Footnote 4 Our identification of conspiratorial bias is novel: while it may not work for all cases, it may allow others to continue building tools on how to detect such discourse in large text corpora. Our methods—and the corpus we provide—may help scholars study the emerging links between populist movements and groups in democracies, foreign governments, and political movements.

Illiberal Political Communication as Election Intervention

Government capacity to generate directed political communication, aimed at foreign publics, represent ways of building up “soft power” in Nye’s term (Nye Reference Nye1984). Soft power is the ability of a state to get another state to act in accordance with the first state’s wishes, which can be accomplished by swaying public opinion in a positive direction (Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2009), or by influencing specific elites (Machain Reference Machain2021).Footnote 5 Political communication is often a key part of “hybrid war” operations (Johnson Reference Johnson2018), a term used to describe measures as diverse as engineering scandals about politicians or launching cyber-attacks on infrastructure.

We use the term government foreign propaganda to refer to any sustained, mass communication to a large audience under the control of a government actor (Lasswell Reference Lasswell1938) that is used with a political objective. It can originate in any regime type: democracy, autocracy, or regimes in between. State-to-state propaganda operations may have a well-defined specific objective (e.g., victory during war), or more diffuse on-going goals such as the promotion of an ideology, particular views on foreign policy issues, or the general good image of the sender.Footnote 6 Under the umbrella term propaganda, we group a variety of different information formats, as we detail shortly.

Regimes with sufficient resources have also tended to direct political communication externally. This includes great and regional powers. All five states holding permanent seats in the United Nations Security Council have broadcasting operations aimed at publics abroad. Soviet propaganda included the government-owned Pravda newspapers and various channels of distribution of the message to external markets.Footnote 7 In the Cold War period, partly in response to Soviet efforts, the United States set up radio programs and other news outlets to publicize the merits of a free society (Cull Reference Cull2008). British and French news operations abroad are especially strong in former colonies.Footnote 8 Chinese news and radio agencies started as a regional operation and now include a global market.Footnote 9

We focus on externally directed, illiberal propaganda of non-democratic regimes. Illiberal propaganda originates as a general domestic pro-regime narrative. It features tropes of overzealous, out-of-touch liberal elites, together with political conspiracies about a corrupt “deep” system, promotes policy paralysis and withdrawal. Promoting identity politics and real or imagined threats increases acceptance of more authoritarian tendencies (e.g., Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009). Fanning political conspiracy theories reinforces a sense of threat, boosting support for strong-man rule. Conspiracy theories render all information suspect, disorienting domestic publics further and defanging political scandals.Footnote 10 By weakening regime critics, and thinning the ranks of their followers, such political communication helps the survival of illiberal regimes (Svolik Reference Svolik2013).

The phenomenon we study straddles state-to-state propaganda and election interventions. We know that all powerful states generate directed political communication abroad: the Voice of America was briefly deemed irrelevant with the end of the Cold War but is now back with a vengeance and in more languages than ever (Cull Reference Cull2008). This type of communication is designed to achieve various desirable goals, such as a better image of the sender state, the promotion of specific ideas, and values. We also know that outsiders, particularly great powers, intervene regularly in the elections of other countries to assure the election of congruent candidates and parties (Bubeck and Marinov Reference Bubeck and Marinov2019). The 2016 U.S. election of Donald Trump has brought this issue home for the American public. One of our contributions is to relate the two. Regimes produce externally oriented political communication, which—when the conditions for engaging in election interventions obtain—turns into an element of a strategy of influence, targeting election outcomes.

Under certain conditions used against election-holding states, state-to-state propaganda may form a part of a strategy of election intervention. A growing research agenda on election interventions documents their impact on public opinion in target states (Corstange and Marinov Reference Corstange and Marinov2012; Shulman and Bloom Reference Shulman and Bloom2012; Tomz and Weeks Reference Tomz and Weeks2020), and on election outcomes (Levin Reference Levin2016). Election interventions are part of foreign meddling in democracy and may impact attitudes toward cooperation with the sending state (Bush and Prather Reference Bush and Prather2020).

We know that election interventions are relatively common, with one in three elections experiencing some form of external meddling (Bubeck and Marinov Reference Bubeck and Marinov2019). Interventions can be of two kinds: democracy-promoting (eroding) ones (Hyde Reference Hyde2011; von Borzyskowski Reference von Borzyskowski2019), and support for specific partisan tickets (Levin Reference Levin2016). Partisan interventions are government-backed attempts to increase the support specific parties or candidates receive at the ballot box. Candidate, or partisan, interventions may involve the tying of foreign aid to the performance of a certain ticket, attempts to aid a political campaign with resources or other means. Such support can be overt or covert, and may or may not involve extensive collaboration between the foreign power and supported actors. There is a great variety of candidate-oriented partisan interventions. About one-third involve help with party campaigning—which may include the production of political communication (Bubeck and Marinov Reference Bubeck and Marinov2019). There is no systematic data, indicating the prevalence of directed political communication as a strategy of election intervention. If the alignment between U.S. channels of communication such as Voice of America and right-wing parties and candidates, on the one hand, and between TASS communiques is any guide, such practices may have occurred frequently.

Foreign powers may not find a domestic political movement that is ideologically congruent and politically viable. In that case, “marriages-of-convenience” can take shape. For example, Soviet interventions in the Cold War often took the form of direct endorsements; the Soviets directly asked Germans to vote not for Chancellor Kohl, but for the Social Democrats in the 1983 election.Footnote 11 Or, even more prosaically, a document would be anonymously leaked with damaging information on a candidate.Footnote 12 Overall, the ideological narrative of Communist propaganda favored leftist parties but this could take a back seat, according to the situation. It is thus little wonder that after decades of a pro-left narrative during the Cold War, in the last two decades the anti-systemic narrative has been more nationalist and populist (Pomerantsev and Weiss Reference Pomerantsev and Weiss2014). From a non-democracy’s point of view, when the political landscape in a targeted country features a viable populist or anti-systemic party, amplifying illiberal propaganda targeting democratic voters would be a natural means of helping an actual or potential ally at the polls.

The type of domestic political discourse produced by illiberal regimes is close to the agenda of populist and anti-systemic parties (Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011)—which aim to undermine the legitimacy of the existing regime (Sartori Reference Sartori1976, 132-3). Populist actors primarily build on the idea that society is ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite,” and argue that politics should be an expression of the will of the people (volonté générale; Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Accordingly, they challenge the political establishment, attempt to undermine its credibility, and claim to give ordinary people a voice in politics in their country (Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016). It has also been noticed that in pursuing their goals, these politicians accuse their opponents of elite conspiracies and propagate conspiracy theories (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2008; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009). These goals and ideas have some overlap with illiberal regime politics that is intended to weaken liberal-democratic governments in the international arena. As populism builds on a unitary notion of the people who are opposed to an evil elite (Mudde Reference Mudde2004), narratives that, for example, challenge minority rights, criticize elites, or claim elite conspiracies against ordinary citizens may help populist parties at the polls. In turn, increased electoral support for them may make it more difficult to form stable governments that demonstrate the strength of democracy and take a clear stance on non-democratic regimes in the international arena.

We focus our attention on an important case in terms of the target of interventions, that of Germany, looking at the discourse surrounding the refugee crisis. We do not seek to appraise how common intervention through propaganda is, or to demonstrate that illiberal regimes systematically support populist movements now. Our goal is more modest. We attempt to explore whether political communication originating in an illiberal regime—Russia—complied with the logic of our argument. It promoted issues that aligned most with a populist party, and communication spiked close to national elections—in a manner consistent with an election intervention. We show, furthermore, that agreement between foreign and domestic illiberal communication consisted of adopting a similar tone on an issue (such as a negative one toward refugees) and of adopting a conspiratorial perspective on the issue.

Illiberal Political Communication during the Refugee Crisis in Germany

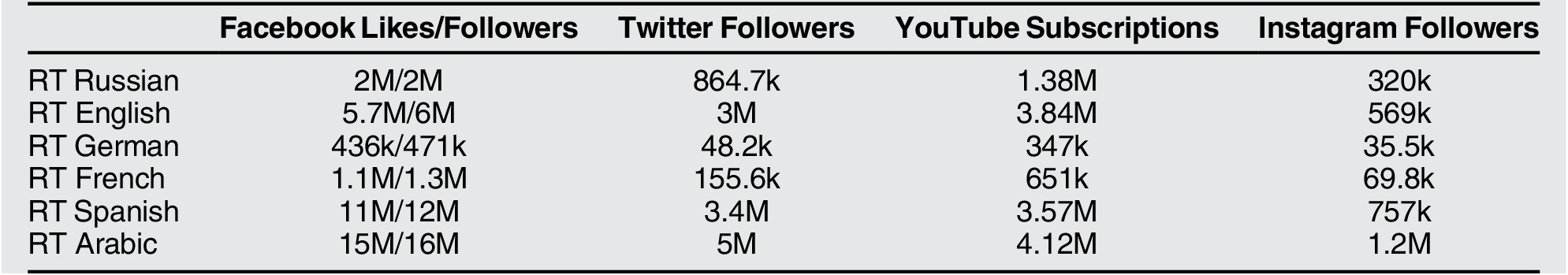

Russia is one of the most powerful illiberal regimes in existence, and is a good test case for some of the propositions we develop. Many of the strategies developed by the Kremlin were first tested domestically (Sanovich, Stukal, and Tucker Reference Sanovich, Stukal and Tucker2021) and then deployed in the West as retribution for Western “meddling” in its own elections (Robertson Reference Robertson2017). The Kremlin was an early adopter of online tools for spreading pro-regime propaganda (Gunitsky Reference Gunitsky2015). The creation of the government-sponsored Russia Today offers a target of opportunity. It is an important bellwether, well linked to the regime (Elswah and Howard Reference Elswah and Howard2020). Table 1 illustrates the reach and scope of Russia Today (RT). There are other operations, such as Sputnik; those are more internally oriented, though over time they have also acquired an international arm.

Table 1 RT operations in different languages

The refugee crisis in Germany has been dramatic, with more than 2.3 million unauthorized crossings into Europe between 2015 and 2017 alone.Footnote 13 The largest share of approved applications for refugee status were granted by Germany (Slominski and Trauner Reference Slominski and Trauner2018). The crossings started an intense debate, between “refugees are welcome” and “migrants go home” (Arlt and Wolling Reference Arlt and Wolling2017), challenging the traditional left-right political establishment (Mader and Schoen Reference Mader and Schoen2019).

For a long time, Germany has been considered an outlier when it comes to electorally successful far-right parties (Dolezal Reference Dolezal, Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2012). Things changed with the advent of the “Alternative für Deutschland” (AfD). Initially founded in early 2013, it primarily voiced opposition to the European Monetary Union and the politics of rescue packages (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2015; Grimm Reference Grimm2015) and almost entered the German Parliament in that year. When the influx of large numbers of refugees set in in 2015, however, the party shifted its focus to opposition to immigration and the intake of refugees (Arzheimer and Berning Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019). With its populist approach, the AfD complemented the Left Party (Die Linke) which is considered by many observers a left-wing populist party (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019).Footnote 14 Depending on the nature of the political agenda, this party may benefit from illiberal propaganda, for example, in cases of economic crises. During the refugee crisis, however, the AfD made a successful attempt at attracting support from critics of the official policy—backed by all mainstream parties, whereas the Left Party did not.

The electoral surge of the AfD took place during the crisis, in a step-wise fashion. Its first electoral breakthroughs were in state (Land) elections, which predated the entry into Parliament with the federal election of 2017. In the state elections held in early 2016, the AfD garnered roughly 13% to 15% in West German states and not less than 24% in Saxony-Anhalt. Later in that year, the party also entered the state parliaments of Berlin and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania by getting 14% and 21% of the votes respectively. In the remaining state elections held before the 2017 federal elections, the AfD also got parliamentary representation, though the level of electoral support was somewhat lower. In these elections, critics of the intake of asylum-seekers and more broadly of immigration were disproportionately likely to cast votes for the AfD (Arzheimer and Berning Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019; Mader and Schoen Reference Mader and Schoen2019). It is thus little wonder that the refugee crisis was characterized as a “present” for AfD by top party leaders.Footnote 15

The refugee issue provides fertile ground for the development of illiberal propaganda. “Subverting culture,” identity politics, and feckless liberal elites are core tropes in such discourse.Footnote 16 In what follows, we test a “spin” proposition (official Russian channels are less likely to push outright lies than online bots), and an “election intervention”/“salience” proposition. The first is a test of whether a specific policy issue distinguished a specific party, and whether foreigners promoted this issue in a manner aligned with and potentially beneficial to that party. The second checks whether foreign sources amplified coverage of the issue (more than domestic sources) close to pivotal targeted elections.

We have argued that the rise of anti-systemic parties generally destabilizes democratic opponents. In the case of the AfD and Russia, Russian interests have been promoted more directly by the party. Members of the AfD have openly promoted reaching out to Russia and trying to fundamentally shift foreign politics in Germany (Wood Reference Wood2020). The ongoing conflict between the moderate and more extreme wings of AfD was decided in July 2015 with a victory for the extreme wing. The winning side was comprised of members who were more hostile to refugees and more firmly in support of the party line of abolishing sanctions on Russia. The victory of the extreme wing possibly contributed to the big electoral breakthroughs in the 2016 state and in the 2017 Bundestag election (Jäger Reference Jäger2021, 7-8). These electoral gains were strongly supported by Russian-German resettlers, usually supporting the CDU and CSU, but decided to switch away when the AfD was more openly holding pro-Russian positions (Goerres, Mayer, and Spies Reference Goerres, Mayer and Spies2020). Additionally, this societal group is also more likely to consume Kremlin-sponsored media, making them more vulnerable to misinformation campaigns (Golova Reference Golova2020). Along with support for Russia in annexation of Crimea and the military aggression in Donbass, the AfD tries to narrate a more positive picture of Russia in German political communication, putting the blame for political and military aggression on the side of the United States of America, NATO, and the German federal government (Wood Reference Wood2020). Ties to the AfD may have provided the Kremlin with “trickle down soft power” (Fisher Reference Fisher2021). We would, therefore, expect political communication to be also used as a tool of election intervention. To clarify: per our argument, an outlet such as RT pursues partly political objectives with refugee coverage, and these objectives increase in value (salience close to elections). Russian sources also pursue other objectives (which is why they do not only talk about refugees), but the value of these objectives becomes secondary in targeted election periods.

The following concepts are relevant in any issue of political communication: salience, spin and misinformation. We want to know what spin Kremlin sources put on the issue of refugees. This includes whether the issue was presented in a positive or negative light, and whether the existence of conspiracy was insinuated or suggested. The reason we focus more on the conspiratorial aspect of stories than any other specific negative theme in the coverage is because the conspiratorial angle may be an important and somewhat overlooked aspect of political competition. In Eastern Europe, it may allow governing parties to effectively hide state capture by appealing to voters with authoritarian tendencies, while shifting criticism to (allegedly) refugee-cuddling reformist oppositions (Marinov and Popova Reference Marinov and Popova2021).Footnote 17 These types of voters may be especially likely to turn against the mainstream. We also check whether coverage of refugees became more salient at certain points. We cover the angle related to misinformation—patently false stories—the least. We are unable to evaluate the factual basis of the narratives. We note, however, that even if semi-official Russian sources (unlike bots) refrained from peddling obvious untruths, a certain amount of spin and suggestions may be equally effective in leading public opinion in the intended direction.

Party Communication

Here, we test to what extent the Kremlin (Russian outlets, operating in German), distinguished themselves from German news sources, by being more negative on the issue of refugees. We also check whether the AfD’s official political communication on the issue of refugees distinguished them from other parties, by being more negative, and whether the AfD and the Kremlin spread conspiracy narratives in a manner that set them apart from other actors.

Proposition 1: The AfD is more likely to be negative on the issue of refugees than other parties, and Kremlin sources are more likely to align with AfD political communication on refugees, measured by negative and conspiratorial sentiment, compared to domestic sources of mass communication.

Party communication: The AfD and other parties on refugees. Press releases are an important tool of party political communication, used by parties to influence public political discourse. As such, they are intended to influence how the media reports about political issues, building a public narrative that follows the party’s frame of the issue. Press releases typically cover only one specific topic and frame the party’s position in a way that is clearly communicated. Furthermore, press releases differ by government and opposition, with governmental parties trying to highlight their successes and opposition parties shedding light on potential failures and shortcomings of government policies (Froehlich and Rüdiger Reference Froehlich and Rüdiger2006).

Sentiment in party communication. We captured the press releases of Germany’s main parties, and classified the refugee-relevant ones. Our procedure for downloading the communications was to identify the homepages where the political parties stored their press releases. We scraped press releases for all parties currently represented in the Bundestag: CDU/CSU, SPD, Greens, FDP, the Left Party, and the AfD. We classified the first four parties as non-populist, mainstream parties, and the latter two as non-mainstream, populist parties for the remaining analysis (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019). We decided to gather the press releases of the parliamentary groups for the mainstream parties and the Left Party, since these parties often did not regularly publish press releases from their party platforms.Footnote 18

We scraped the content from the homepages. We used both classical web-scraping and JSON-extraction. Next, we used natural language processing (NLP) techniques to find stories that are semantically related to our dictionary (in the online appendix, A.1) that includes a set of terms describing the topic under study: refugee stories. Essentially, we need to see which releases are about refugees. A human would do this easily, for a small number of stories. We have a lot of data, and so we rely on automatic methods while using humans to validate or check the quality of the output on a small subset of the articles. One basic automated approach is to use keywords: humans define the encounter of what keywords in an article would make it “about refugees.” Another approach uses word-embeddings or “the company words keep”—a type of numerical representation of words that permits words with similar meaning to have a similar representation. If an article has words that are close to refugees, as observed in a very large corpus of data, it is labelled as refugee-relevant.Footnote 19 We rely on both the key-words based technique and word embeddings.Footnote 20

After retrieving only the refugee-relevant texts, we take a look at the press releases by party. We note that the AfD devotes far more of its attention to the refugee topic than other parties: nearly one-quarter of its releases deal with the topic, as compared to 6%–7% for the governing parties (figure 4 in the online appendix). Thus, this is a salient issue for them.

Next, we perform a sentiment analysis on the resulting text dataset of refugee-related press releases. We simply count the number of occurrences of positive words and negative words in each month of our corpus and calculate the proportion of positive words in the total number.Footnote 21 We note that the resulting proportion should not be interpreted relative to some abstract and absolute notion of positive; a sentiment score of 0.55 is more than half positive words but a human may perceive that the article is quite negative overall. Rather, we claim that a higher score means more positive coverage, but whether that means truly positive or simply less negative is a different issue.Footnote 22 Validation of the scores by humans is a common way to establish that sentiment analysis measures what the researcher wants, and to anchor what negative and positive truly mean. This also helps position in perspective and correctly evaluate the size of the observed differences. We had human coders rate independently a random sample of 150 political texts in positive, negative, and neutral terms, as far as sentiment toward refugees is concerned. Figure 8 in the online appendix, party panel, shows that small changes in sentiment score map into large differences in human judgement. Essentially, stories below 0.65 are negative according to humans, and stories above this number are positive.Footnote 23

With that in mind, we compare the parties’ scores on figure 1 by month. AfD has a lower proportion of positive words than the other parties, a result which is statistically significant in a two-way difference-of-means t-test. For the test, we aggregate all mainstream parties and contrast them with the sentiment scores of the AfD over the whole time span. The average proportion of positive words is at about 0.59 for the AfD, for the mainstream parties it amounts to 0.64 with a statistically significant difference (t = 5.58). Despite some variation over time, the AfD was more critical in their press releases than mainstream parties.

Figure 1 Sentiment analysis: AfD versus Mainstream parties combined on refugees

Note: Proportion positive words (positive over positive+negative over month). Dashed line shows lower bound of what humans consider a positive story. Based on 1,265 total number of documents.

We further note that populist parties can be on the left and on the right; our argument does not specify exactly which party would benefit from foreign communication. In the case of Germany, die Linke championed refugees (as being hurt by a global capitalist system), and painted the enemy group in radically different terms from the AfD. Electorally, attacking refugees has been the winning issue politically in Europe, and that may have affected the direction of the Kremlin’s coverage.

Conspiratorial bias in party communication. Parties in Germany do not pander conspiracy theories overtly in terms of remarks officially printed in, say, party positions. When we broaden the look beyond official communications, we note that whereas German mainstream parties refrain from employing conspiratorial language in any channel, the AfD does have a history of pandering conspiracy theories in certain types of media. The AfD is particularly active in Twitter and on YouTube where they are able to directly communicate with their supporters. Furthermore, board members of the AfD give interviews to right-wing newspapers and broadcasters, which deem themselves as an alternative to “mainstream media.” Conspiracy theories are also triggered in speeches of board members to party members in closed or semi-public party meetings. In each of these communication channels, members of the AfD refer to conspiracy theories even though it might not be part of their official political communication.

During and after the refugee crisis, references to conspiratorial theories have been widespread in some parts of society (Molz and Stiller Reference Molz and Stiller2019). Especially in right-wing audiences, theories on ethnic inversion (“Umvolkung”) were prevalent. This narrative shows up for decades in the extreme right but never has been made so public as during the refugee crisis (Harris Reference Harris2001; Rosellini Reference Rosellini2020). On Twitter, Beatrix von Storch, an AfD board member, is known for spreading the ethnic inversion conspiracy frequently to frame the opening of the borders for refugees as a plan for replacing the white German population by immigrants from African and Arab countries.Footnote 24 On YouTube, similar references can be found in videos, which were produced by the AfD broadcaster (AfD-TV) during the discussion on the Global Compact for Migration.Footnote 25

When giving interviews with right-wing newspapers and broadcasters, AfD members often change their lingo very significantly compared to their official political communication. When giving interviews to Compact and PI (Politically Incorrect), we find clear references to conspiracies in general and on ethnic inversion in particular.Footnote 26 Politicians of the AfD are even willing to pick up these conspiracies in their speeches, however, being more careful about the terms used in order to prevent observation by internal intelligence authorities. Björn Höcke uses the yearly meeting of the far right-wing part of the AfD to refer to several conspiracy theories, including both ethnic inversion and plots of the government with other nations.Footnote 27 Finally, there is evidence that the floor leader of the AfD, Alexander Gauland, also referred to this conspiracy when speaking in the plenary debate of the Bundestag,Footnote 28 making the conspiratorial bias of the AfD very visible for a broader audience.

Mass Communication

Next, we want to appraise the role of foreign and domestic sources of communication on refugees. We focus on two Kremlin media channels broadcasting online in German: Sputnik.de and RT Deutsch (Spahn Reference Spahn2018). Sputnik.de and RT Deutsch began operations at an opportune time—in the middle of November 2014, just as the number of asylum-seekers arriving in Europe started to tick up. Sputnik is a more voluminous operation, one that extended and rebranded abroad an existing domestic Russian service. Russia Today was specifically created for the Western media market. Given this original intention, we would expect to see that RT is more attuned to strategic goals in this case, namely, to feature more negative coverage, more conspiracies, and to depend more on the election calendar.

The case of a young girl (“Lisa”) went missing for a few days in Berlin exemplifies this strategy very well. In January 2016, a young girl was announced missing by her German-Russian parents. When she re-appeared a few days later, she argued that she had been kidnapped and raped by some “southern-looking” men. Although during police interviews it became quickly clear that the girl made up the story, Russian media—RT Deutsch among others—reported intensively on this case. Russian media spread conspiracies for weeks that refugees were responsible for committing the crimes against the young girl, arguing that the police were not willing to resolve crimes committed by refugees.Footnote 29 Additionally, they accused German mainstream media to spark anti-Russian sentiments in the German public, aiming to reach their strategic goals of destabilizing mainstream political elites.Footnote 30

Sentiment in mass communication. To put the coverage of the issue by the Russian sources into perspective, we compare it to the coverage by domestic sources. Specifically, we examine German media, including the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ—center-right, on the political spectrum), the Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ—center-left), Welt (center-right), Tageszeitung (TAZ/left), and Bild (tabloid). We start by scraping the entire corpus of more than 700 thousand articles published by those outlets.Footnote 31 Next, we use the same Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques described earlier in reference to party political communication to retrieve only refugee-relevant stories from our corpus.Footnote 32

This yields a total of 25,450 stories, for the period spanning the start of 2014 to the end of 2018 (broken down by news outlet in table 5). At the height of the crisis in the summer of 2016, there were some fifty refugee-related stories across the different outlets daily, marking the topic’s importance. There is a difference between the German and Russian outlets. Among the German ones, coverage ranges between 1% (Welt) and 10% (FAZ), with the mode being 6% (TAZ). The Russian outlets range between 11% (Sputnik) and 15% (RT). Russian media broadcasting in Germany focuses more of their attention on the topic of refugees than the modal German outlet during the period under study, an observation which is consistent with the posited influence operation pursued by those outlets. The high interest in some German media in refugees should come as no surprise—the challenge of accommodating the refugees has been one of the most significant political challenges in the history of the Federal Republic.

We next run a sentiment analysis on the monthly aggregated content, using the same procedure as described in the party communication section. Figure 2 shows the positive-words ratio of the refugee-related stories, by month, of the German and Russian publications. Russian sources are more negative, a result highly significant in a difference-means test. We aggregate Russian and German outlets and test for differences in mean over the whole time span. The Russian sources show on average a proportion of 0.53 positive words, whereas the German outlets are considerably more positive with about 0.57. The differences between the means is statistically significant on the 95% confidence level (t = 4.99). The online appendix section B.1 presents sentiment results by outlet. As expected, RT has the lowest score: when only considering RT, the average proportion of positive words drops to 0.49. We should emphasize the importance of tailoring: Sputnik mostly re-translates Russian domestic propaganda, which was more focused on issues other than the Western European refugee crisis. While illiberal in nature, Russian domestic messaging may differ in emphasis from the most effective message from an external point of view. This encourages further thinking about how deflecting attention from domestic problems and intervening in foreign political discourses relate.Footnote 33

Figure 2 Sentiment analysis: Russian media (Sputnik and RT) versus German (left, FAZ, TAZ, Welt, Bild, and SZ) on refugees.

Note: Proportion positive words (positive over positive+negative over month). Dashed line shows lower bound of (what human coders consider) positive stories. Based on 25,450 total number of documents.

We conduct a validation analysis on a random sample of 150 pieces of text in order to see how humans would rate stories classified as more or less positive by the automatic scoring. Small changes in the sentiment score map into large differences in human judgement.Footnote 34 As human judgement turns more positive, so does the mean automated score. It turns out that stories with a score of 0.55 and above are positive, and stories with a sentiment score of less than 0.55 are perceived as negative.

Figure 9 shows breakdown by outlet. Russian outlets have significantly more negative coverage than all other outlets. In fact, they exceed significantly even Bild, a national tabloid. One may note that German mass media outlets feature a more negative words ratio than the AfD in its press releases. This may reflect differences in the nature of communication mediums. Official party political text likely follows conventions that are different from news media reporting. We note that human coders find different cut-off criteria for positive versus negative stories for the two types of communication, which is consistent with the idea of different communication styles being used (0.65 for the cut-off to negative for political communications related to parties and 0.55 for communication related to papers).

Conspiratorial bias in mass communication. We argue that promoting conspiracies plays into the hands of local actors in Germany, appealing to supporters of non-mainstream parties. We also argue that it links up the “threat” refugees pose to ways in which the Kremlin has been “wronged” (by pro-democracy movements, sanctions) and thus it advances the Kremlin’s geo-political objectives by making everything connected in a single arc of evil.

Anecdotal evidence suggests the wide use of conspiratorial tropes by Russian sources. The theme of Muslim refugees “invading” the EU is an integral part of the “effeminization” of the West trope in Kremlin communication (Cushman and Avramov Reference Cushman and Avramov2021).

On the issue of refugees, we attempt to identify the systematic conspiratorial bias in mass communication. We use NLP approaches to get deeper into the content of the articles and measure their relatedness to the topic of conspiracy. We generate a set of keywords for these topics based on our reading of a broad array of articles across outlets. These include general terms about secrets, hidden government documents, plots, “world leaders”—masters of geopolitical intrigue.Footnote 35

In the case of the Kremlin, conspiracy is often traced to George Soros, his Open Society foundation, and the color revolutions liberals are presumed to abet or even direct.Footnote 36 We expect Kremlin sources to feature more of this language. Conspiracy-pandering not only presents the government in a bad light, but it also discredits the establishment more broadly and so plays into the hands of the AfD.

Conveniently, it creates a link to other issue-areas, in which the Russian government wants to sway public opinion. Thus, if Open Society and Western elites are the same actors who brought in refugees and who staged the Maidan protests in Ukraine, then all their actions, including democracy-promotion and the sanctions against Moscow, are illegitimate.

Figure 3 shows a density plot comparison in regard of the use of conspiratorial language between the two Kremlin newspaper sources and the five German ones, for all refugee-relevant stories in the period under study. The red line represents the density of German media and the dotted black line illustrates the same for Russian media.

Figure 3 Conspiracy language

Note: Russian/German media - broken/solid line

To create the conspiracy scores for Russian and German news, we compute a similarity score between each article’s words and conspiracy-related topic words using two types of word-embeddings.Footnote 37 Though there is no black-and-white pattern, distinctions are visible. For conspiracy, the fiftieth percentile of similarity on Russian media coincides with the seventy-fifth on German media.Footnote 38 A comparison of means test confirms that these differences pass conventional levels of statistical significance.

We conducted a validation check, to ensure that classification matches human judgement.Footnote 39 When we take a closer look at the conspiratorial language within the Russian sources, we find that RT has a higher overall conspiracy score than Sputnik. Thus, conspiracy-pandering is especially valuable on democratic media markets.

We next conducted an ablation study by removing sequentially each word in our conspiracy-topic dictionary and re-calculating the produced results, to see which words increase similarity score in regard to conspiracy language the most. Figure 11 in online appendix D shows that Open Society, Euromaidan, and “interference” are among the most influential words driving conspiracy similarity. This confirms that one of the goals of pushing such stories may be to link domestic political debates in democracies to organizations and events that the Kremlin views as menacing, such as Western policy toward Russia and its neighborhood, while delegitimizing the welcome extended to refugees.

We should note that RT and Sputnik in German do not pander the most extreme versions of conspiracy theories. There are no accounts of lizards deciding world affairs. This may be due to norms of acceptable materials that they have to abide by or risk backlash in Germany. The channels hint and insinuate. An effeminate Europe on its knees is a complex figure that links up the fight for gender identity (and the myth of a liberal agenda gutting the West’s strength) to an image of defeat by “religious infidels.” This can be easily related to a more complex conspiracy out there (e.g., by Soros) but the dots are to be connected in the readers’ imagination. We do not claim that we address the many fascinating complexities that come with conspiratorial narratives. We have merely taken a first step to flag such (related) discourse in a very large body of media publications and we hope future research can continue the analysis we start.Footnote 40

From Mass Communication to Election Intervention

Here, we examine whether Kremlin-sponsored coverage increased closer to German elections, in particular close to the federal election of 2017, the election most likely to affect national policy.

Proposition 2: Kremlin sources will show disproportionate interest in refugees close to elections as compared to domestic mass media: with a spike especially likely for RT, and for the national elections.

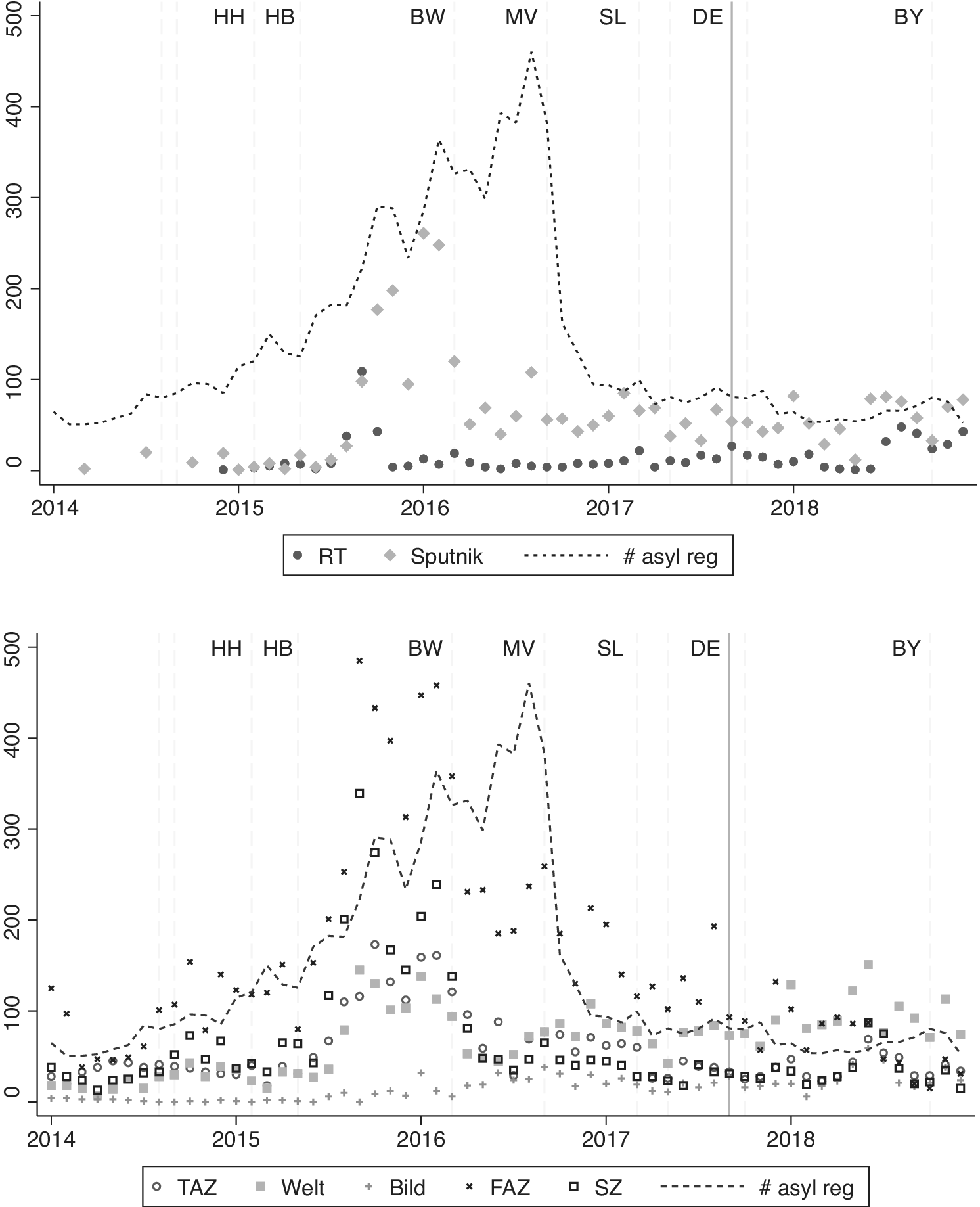

To help visualize the data, we aggregated the daily stories and created a scatter plot by month in figure 5. The figure also includes asylum registrations in Germany (‘# asyl reg’ line), based on monthly data from Eurostat.Footnote 41 The applicant numbers are not labeled but the lowest number—10,175—of asylum seekers is observed in February of 2014, and the highest number is recorded in August 2016—92,115 registrations. The graph carries dashed lines for state elections and with a solid line for the federal election in the period. There are a total of seventeen different polls, held on fourteen distinct dates (table 2).

Table 2 German elections (land and federal)

We see that some German outlets devote more attention to the topic close to state elections taking place in the months of March and September of 2016. This is the period of the highest number of refugee-registrations and of the British referendum on leaving the EU. Russian outlets share some of this tendency. Kremlin-affiliated media seems to devote disproportionate coverage close to the ensuing elections in March 2017 (Saarland) and in the federal election of September 2017.

A direct comparison would have the advantage of simplicity, but it cannot properly capture trends impacting all outlets at the same time in a similar manner. If high levels of arrivals, or some other variables, are driving interest in the refugee topic, we need some way of accounting for these factors. In addition, what we are truly interested in is comparing the relative spikes of election-related interest across publications. Do Kremlin-aligned media experience more/stronger spikes relative to German media?

We adopt an event-study estimation approach to answer this question. Frequently used in financial economics, this approach tries to establish whether some events produce “abnormal” returns in the portfolios of some firms but not others (MacKinlay Reference MacKinlay1997). All stock returns are hypothesized to behave the same way, prior to some shock hitting some but not others, at which point their returns diverge: revealing that the shock has differential effects on a theoretically relevant subset. For example, when Suharto had an operation for a heart bypass, politically connected firms experienced a nose-dive reflective of the risk that political connections will lose value if the operation went awry.Footnote 42 Other firms’ returns did not budge in value nearly as much.

Key in those approaches is defining an estimation window and an event window. The estimation window helps determine each firm’s expected stock return (at any time, leading up to and during the event). The idea is to use the estimation window outside of the event to develop a predictive model of returns, which is then applied to the event window: the difference between expectation and actual return provides evidence about whether or not expectations diverge significantly from what is observed. If yes, we conclude that the event is indeed a significant factor for abnormal (higher or lower) returns in the selected stocks. Formally, the model is summarized by Equations 1 and 2.Footnote 43 We adjust the notation to our case. The average election-window effect (the divergence we are looking for) is defined as the average abnormal publication per day, a deviation calculated as a mean and confidence interval based on the difference between prediction and observation in the event window of daily stories on refugees.

$$ \begin{array}{c}\hskip-11.5pc \underset{\mathrm{Observed}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{R_{i0}}}=\\ {}\hskip-4.8pc \underset{\mathrm{Expected}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{R_{i0}^{\ast }}}+\underset{\mathrm{Abnormal}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{\varepsilon_{i0}^{\ast }}}\end{array} $$

$$ \begin{array}{c}\hskip-11.5pc \underset{\mathrm{Observed}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{R_{i0}}}=\\ {}\hskip-4.8pc \underset{\mathrm{Expected}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{R_{i0}^{\ast }}}+\underset{\mathrm{Abnormal}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{\varepsilon_{i0}^{\ast }}}\end{array} $$

$$ \hskip-2.8pc \underset{\mathrm{Average}\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Election}\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Effect}}{\underbrace{p}}=\underset{\mathrm{Average}\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Abnormal}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{\frac{1}{N}\sum \limits_{i=1}^N{\varepsilon}_{i0}^{\ast }}} $$

$$ \hskip-2.8pc \underset{\mathrm{Average}\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Election}\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Effect}}{\underbrace{p}}=\underset{\mathrm{Average}\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Abnormal}\hskip0.5em \#\hskip0.5em \mathrm{Publications}}{\underbrace{\frac{1}{N}\sum \limits_{i=1}^N{\varepsilon}_{i0}^{\ast }}} $$

For the event window, we use the one-month period before and after an election (-30 to 30 days from the poll). This is our event=1 (shock) period. For the estimation window, we use the outlying one-month period in each direction: so the -60 to -30 days (period before the poll), and the 30 to 60 days (period after a poll). This is our non-event, or event=0, period. In this period, underlying factors are most likely to be similar, and so this period should be most comparable to the election-proximate, event=1, period.Footnote 44 We need at least several weeks before the election to capture the campaigning period. We also want to capture the period following elections, since the results are discussed, coalitions are formed and broken, and this, to us, is still a salient period for discussing political issues with a view toward damaging a political target.

The data, presented in table 2, presents some challenges. The two earliest elections fall outside of the period of operation of RT and Sputnik and cannot help identify the effects of election proximity on coverage. Of the remaining elections, some take place right after another: Lower Saxony held elections three weeks after the federal election. That poses issues with identifying the effects of election period: in October, if we are right, outlets should start responding to the end of the federal election period by decreasing coverage but the nearing state election may offset some of the expected decline. This would bias our test against finding an effect of the kind we are after.

To deal with that, we merge elections less than two months apart into a single event, defining the period between them as part of the election window (we still include the thirty days before the earliest election and the same period after the latest election in the event window). This affects, in particular, the Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Berlin Land elections; the Saarland, Schleswig-Holstein, and North Rhine-Westphalia ones; the Bundestag election and the Lower Saxony Land election; and the Bavaria and Hesse Land elections. Altogether, we have seven election events, labeled in figure 5 by the Land abbreviation of the (earliest, or first alphabetically) state holding a contest: ‘HH’ for Hamburg, ‘SL’ for Saarland and Schleswig-Holstein, and so on (we use ‘DE’ for the federal, Bundestag election).Footnote 45 Our interest is to compare the number of stories within and outside of an event-window, for each of the seven election periods.

We use the estimation period to construct a model of how a particular news outlet publishes on refugees. To take the example of Sputnik, we fit an OLS model predicting Sputnik’s interest in refugee publications as a function of all German outlets’ interest during the same period and the number of asylum-seekers. We do the same for RT. Then, we use the fitted coefficients to estimate expected coverage in the election windows based on the same regressors. If this expectation deviates significantly from what we actually see, then we have “abnormal” coverage. Note that if German outlets are affected by the election, the approach should still work since we want to know whether Kremlin-aligned ones are affected \emph{more} (i.e., exhibit abnormally high coverage).

The results are shown in Figure 4. Standard errors and p-values are calculated using asymptotic t-statistics (MacKinlay Reference MacKinlay1997).Footnote 46 There is no evidence of higher interest in elections close to Land contests; indeed, in some cases the two Russian sources covered refugees less heavily than German outlets. Things look different, when it comes to the federal election. RT Deutsch, but not Sputnik, publish 0.3 more stories per day in the month before and after the national (DE) election. Considering the daily average of 0.5 stories, this is a significant increase of 60%. RT, set up specifically as a foreign broadcasting operation, again exhibits more “propagandistic opportunism.” When it matters, the channel appears to broadcast more political communication on a topic favoring a locally aligned party—at rates exceeding domestic media interest in the policy issue. Salience increases with elections.

Figure 4 Event study: Deviation of observed from expected daily refugee stories

Note: 95% CI. DE = Federal Election.

Figure 5 Refugee stories by outlet, with elections

Note: Refugee stories by outlet (monthly), with elections (state/federal - broken/solid vertical lines). Asylum registration trend shown for comparison and not to scale.

Importance of Foreign Political Communication in the Elections

Populist and anti-systemic parties, particularly on the right wing, have been on the rise in many democracies for at least a decade (e.g., Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019). A growing literature has identified a number of factors facilitating the success of these parties: large-scale processes of international economic cooperation, migration, and political integration that provoked public opposition that fueled support for these parties (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). Others pointed to changes in the communication, in particular, the rise of the Internet and social media as a facilitator of the electoral success of elite-challenging, populist actors (Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017; Schaub and Morisi Reference Schaub and Morisi2020). We extend this debate by showing how information coming from abroad may have contributed to the success of populist parties in democracies.

We identify a strategy of election interventions that is novel and difficult to discern. Being a part of ongoing state-to-state communications operations, this type of intervention can only be identified through comparative analysis of trends relative to events and other sources of communication. We argue that illiberal regimes promote illiberal propaganda abroad, and that coverage should increase close to elections in democracies. Our case work suggests that Kremlin-controlled media promoted refugee stories, an issue beneficial to the populist far-right AfD party in Germany, in a manner more similar to the way the AfD approached the issue. Kremlin sources, and specifically the external propaganda outlet RT, promoted more negative sentiment and conspiratorial narratives—mainstays of AfD political communication. We also find that Kremlin-controlled outlets published more on the issue specifically close to the federal election, the contest that mattered most.

How might this coverage have helped the AfD? First, there is the direct reach of the channels which, according to our evidence, amounts to 6%–7% of Germans getting their news directly from the Kremlin outlets.Footnote 47 Second, there is the indirect reach. RT and Sputnik are part of an ecology of entertainment channels, including Ruptly, InTheNow, and others. These would take content from RT and mix it to push out infotainment, without the source being necessarily recognizable (RT itself often uses nondescript acronyms such as RNA). We know that some of these outstrip German media in popularity. In addition, we know that much of RT’s and Sputniknews’s content is picked up on Twitter. Some Twitter hashtags become viral.Footnote 48 The contents produced by RT and Sputnik get coverage of other media, thereby influencing public discourse—not least by making certain topics legitimate. This certainly happened in the “Lisa” case of a German-Russian teenager allegedly abused by refugees, and it happens more broadly when results of public opinion surveys, commissioned by these Russian sources (or appearances of German politicians on RT or Sputniknews), attract attention in the media.Footnote 49 Third, AfD party activists and leaders used the Russian channels in their political communications. A survey of party activists found that the RT Facebook page was the most liked information resource, preceded only by the Facebook pages of the party page and the page of the Pegida movement.Footnote 50 Given that mainstream media shunned the topics promoted by the AfD, access to an outlet with friendly political communication may have played an outsized role for mobilization purposes (Rone Reference Rone2021).

What was the ultimate effect of this on the campaign in terms of views on refugees, support for AfD, voters cast? We lack an identification strategy to answer these questions at present. It has been demonstrated that negative framing of refugees influences mass attitudes: support for redistribution and integration diminishes (Avdagic and Savage Reference Avdagic and Savage2020). We also refer to studies of political communication that demonstrate that consistent messaging has a non-trivial effect on party support and electoral outcomes (DellaVigna et al. Reference DellaVigna, Enikolopov, Mironova, Petrova and Zhuravskaya2014; Adena et al. Reference Adena, Enikolopov, Petrova, Santarosa and Zhuravskaya2015; Butler and De La O Reference Butler and Ana De La2011; Crabtree and Kern Reference Crabtree and Kern2018).

Whatever the relationship between media coverage of migration and the electoral performance of the AfD,Footnote 51 the AfD’s rise has had wider implications for German domestic politics. With increasing electoral gains of the AfD since 2014, German politics changed dramatically both on the regional and the federal level (Schmitt-Beck Reference Schmitt-Beck2017). On the federal level, the surge of the AfD changed politics considerably. With almost 13% vote share in the 2017 federal election and considered by all other parliamentary parties as not a potential coalition partner, the entrance of the AfD in the Bundestag prevented any two-party coalition despite the so-called “Grand Coalition,” composed of CDU/CSUFootnote 52 and SPD, which was originally meant to be a coalition only to be formed in times of emergency (Bräuninger et al. Reference Bräuninger, Debus, Müller and Stecker2019). After an attempt at forming a novel coalition comprised of CDU/CSU, the liberal FDP, and the Greens had failed, CDU/CSU and -grudgingly- SPD agreed to form yet another coalition government—after an unprecedentedly long process of government formation (Gärtner, Gavras, and Schoen Reference Gärtner, Gavras and Schoen2020). This example nicely demonstrates the challenges the entry of the far-right AfD poses for electoral politics and governing in Germany.

What does our work suggest for other cases? We know that the Kremlin’s combination of truths, half-truths, and plain lies forms a powerful information campaign, reaching many markets—in Europe,Footnote 53 North America, and beyond. Ramsay and Robertshaw (Reference Ramsay and Robertshaw2019) show how widespread the Russian information influence is, targeting a large number of European states. In Eastern Europe, the issue of the refugees has empowered right-wing parties (Bustikova Reference Bustikova2019). It is also notable that once a certain narrative is distributed, other regimes and interested actors can pick it up and amplify it. In the ecology of illiberal regimes, some more powerful and some less, certain actors can participate in the production of the propaganda that we identify—and others use it for their advantage, while also passing it along. The mechanism and methods we flag can help others work to delineate a new emerging bloc of political affinities in world affairs (Koesel and Bunce Reference Koesel and Bunce2013), one that connects political movements of a certain bent across borders. Questions for further research include the relationship between conspiracy narratives and support for authoritarianism, the links between domestic and external propaganda, and what part directed political communication plays in issue- and party-oriented election interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their help; the usual caveat applies.

Supplemental Materials

-

A. Party Political Communication

-

B. Mass media Data

-

C. Validation of Sentiment Scores

-

D. Procedure and Keywords for Similarity to Conspiratorial Language

-

E. Event Analysis

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721003108.