In the summer of 2017, Republicans in Congress worked feverishly to repeal President Obama’s landmark healthcare law, the Affordable Care Act. Many Republican Senators and Representatives won or retained office campaigning against “Obamacare” (Williamson, Skocpol, and Coggin Reference Williamson, Skocpol and Coggin2011; Aldrich et al. Reference Aldrich, Bishop, Hatch, Hillygus and Rohde2013; Mak Reference Mak2018). Yet their new plan to “repeal and replace” the law was unpopular, dividing Republican voters (Murray Reference Murray2017). Moderate Republicans found themselves stuck between an electoral mandate and potential backlash. How did representatives approach this dilemma? Congressional staffers delved into constituent communication databases and compiled the correspondence that offices received about the repeal bill. One chief of staff described the process his office used to track opinion this way:

We put people into three buckets: Those who opposed repeal because they wanted to keep [the ACA]; those who opposed repeal, or the House version of the legislation, because they didn’t think it went far enough; and those who supported the bill.Footnote 1

By tallying the e-mails, phone calls and letters that the office received in each category, his staff estimated that a majority of engaged constituents opposed the bill. Lawmakers and their staff also sat down with interest groups to solicit their views, including health insurance companies and the AARP (Gibson 2017; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2017).

Understanding whether and how Congress represents the public’s policy preferences is a central question in the study of American politics (Wright, Erikson, and McIver Reference Aldrich, Bishop, Hatch, Hillygus and Rohde1987; Stimson, MacKuen, and Erikson Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995; Erikson, MacKuen, and Stimson Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002; Canes-Wrone Reference Canes-Wrone2015). Past research demonstrates that elected officials’ responsiveness to their constituents is highly uneven. Politicians and their staffs tend to measure public opinion imprecisely and therefore misperceive their constituents’ preferences (Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963; Herbst Reference Herbst1998; Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018; Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019). They also respond disproportionately to co-partisans, the affluent, and the organized (Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Lax, Phillips, and Zelizer Reference Lax, Phillips and Zelizer2019; Maks-Solomon and Rigby Reference Maks-Solomon and Rigby2019; Wright and Rigby Reference Wright and Rigby2020; Grossmann, Isaac, and Mahmood Reference Grossmann, Isaac and Mahmood2021). Not only do these inequalities mark a departure from the democratic ideal that policy corresponds to majority opinion, they raise questions about how politicians learn about their constituents’ views in the first place.

To the degree that the people are sovereign, their influence primarily lies in determining the issues to which offices devote the greatest attention (Bachrach and Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962; Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1975). On salient policy issues, Congressional offices still listen to their most vocal constituents. Yet on the vast majority of issues, constituents are all but silent (Burstein Reference Burstein2014). When Congressional offices are not hearing from constituents, they reach out to the organized groups representing constituencies with a stake in the policy at hand (Monroe Reference Monroe2001; Miler Reference Miler2007). Indeed, political elites often conceptualize public opinion as synonymous with interest groups (Herbst Reference Herbst1998). As one legislative director put it:

In the cases where stakeholders and constituents are not engaged on an issue, those are the issues where you reach out to people and say this is going to affect you, get your act together. Those are cases where we’re more proactive, because we want to hear from somebody.Footnote 2

From education to healthcare to energy, Congressional staff seek out the people who are “living under the law,” requesting their opinions on proposed legislation.Footnote 3 This “provoked petitioning” challenges conventional models of lobbying that put the focus on interest groups reaching out to elected officials (Bombardini and Trebbi Reference Bombardini and Trebbi2020). Representatives and their staff do not merely respond to contact from organized interests, but elicit opinions, contributing to the mobilization of bias in the political system (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967; Schattchneider 1975; Disch Reference Disch2012; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012). Offices maintain regular contact with interest group representatives, seek out civic association meetings in the constituency, and pay close attention to the questions that constituents raise at town halls.

In this paper, we describe how the contemporary Congress undertakes representation in practice. We draw on both original interviews and a survey of senior Congressional staff to examine how offices learn their constituents’ priorities and preferences. Congress has a suite of modern tools to gauge constituent preferences: databases to record and track constituent correspondence, including e-mails; public opinion polls, including downscaled estimates from multi-level regression with poststratification (MRP) models that permit district-level opinion estimates; in-person meetings with constituents and group representatives; and town hall meetings (Grimmer, Westwood, and Messing Reference Grimmer, Westwood and Messing2015; Hersh Reference Hersh2015; Hager and Hilbig Reference Hager and Hilbig2020; Sekar Reference Sekar2020). However, offices rely far more on some tools than others. Despite the widespread attention polling gets in the news and public discourse (Leeper Reference Leeper2019), members of Congress rarely use polls to ascertain their constituents’ views on policy. Instead, offices rely on the same methods observed decades ago (Fenno Reference Fenno1977; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984), relying on politically active constituents and interest groups. Congressional staff use sophisticated constituent correspondence databases to respond to the constituents most likely to shape their re-election prospects; tend to discount or ignore the mass campaigns that advocacy groups organize online; and rely on interest groups for advice on legislative decisions. As a result, the incoming and outgoing channels of information on constituents’ preferences paint a picture that disproportionately reflects the views of the vocal and the organized. Despite Congress’s ability to use modern tools to conduct the chorus of representation, their methods still give the loudest singing roles to voices with a “strong upper-class accent” (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1975).

The Mechanisms of Representation

For over half a century, political scientists have debated whether politicians respond to public preferences on policy. Research has focused on the conditions under which public preferences matter, and to whom politicians are most likely to respond (Downs Reference Downs1957; Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963; Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1975; Canes-Wrone Reference Canes-Wrone2015). Although policy rarely aligns perfectly with public opinion, evidence suggests that representatives change policies in response to shifts in the public’s ideological leanings (Wright, Erikson, and McIver Reference Aldrich, Bishop, Hatch, Hillygus and Rohde1987; Stimson Reference Stimson1991; Stimson, MacKuen, and Erikson Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995; Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018). Such responsiveness is encouraging for democratic accountability.

However, a growing body of research has uncovered some troubling patterns. Representatives often respond more to wealthy citizens, interest groups, and members of their own political parties than to the public writ large (Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Lax, Phillips, and Zelizer Reference Lax, Phillips and Zelizer2019; Stokes Reference Stokes2020). After controlling for affluent Americans’ and interest groups’ preferences, scholars do not find a relationship between the middle class’s preferences and public policy decisions (Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Bowman Reference Bowman2020). Representatives are also more likely to be responsive to non-minority than minority constituents (Butler and Broockman Reference Butler and Broockman2011; Broockman Reference Broockman2013; Butler Reference Butler2014; Costa Reference Costa2017), a bias that cannot be explained by the demographic composition of representatives’ districts (Einstein and Glick Reference Einstein and Glick2017; Mendez and Grose Reference Mendez and Grose2018). More broadly, these distortions suggest that there is not a simple link between public opinion and policy.

To understand representation, we must attend to mechanisms. How do politicians gather information to estimate the public’s preferences? Political staff play a central role (Salisbury and Shepsle Reference Salisbury and Shepsle1981; Montgomery and Nyhan Reference Montgomery and Nyhan2017; Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019). In response to Congress’ increased complexity and workload, lawmakers have delegated critical tasks to aides based in the District of Columbia (Hall Reference Hall1996). Legislators also have offices in their districts and states staffed by field representatives assigned to particular geographies or issues (Monroe Reference Monroe2001). These national and constituency-based staffers gather policy-relevant information; communicate with constituents, interest groups, and government agencies; and advise members on legislative decisions such as votes, co-sponsorships, and legislative participation (Hall Reference Hall1996; Costa Reference Costa2020). As Miler (Reference Miler2010, 27) argues, political staff are “the primary link between the legislative office and constituents, as well as between the office and organized interests in the policy community.”

Understanding the tools and procedures staffers use is all the more important given how new technology may be reshaping the process of representation. In an era of widespread polling, presidents have devoted substantial resources to tracking—and shaping—public opinion (Jacobs and Shapiro Reference Jacobs and Shapiro1995; Druckman and Jacobs Reference Druckman and Jacobs2006; Hager and Hilbig Reference Hager and Hilbig2020; Stokes Reference Stokes2020). Yet Congressional representatives do not enjoy a similar supply of information. State- and district-specific polls are both expensive and uncommon, and when they exist, are more likely to be horse-race polls during elections (Herbst Reference Herbst1998). Surveys of state politicians running for elected office, for instance, find that a majority do not conduct polls (Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018). Partially as a result, politicians and their staff misestimate their constituents’ opinions as measured by polls, even on highly salient issues like healthcare (Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018; Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019).

If not through polls, how do politicians and their staff measure public opinion? Before widespread Internet adoption, research suggested they read newspaper editorials, paid attention to the topics covered in the media, met with trusted constituents, and listened for comments and questions at public meetings in the constituency (Fenno Reference Fenno1977; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984). However, with some exceptions (Hager and Hilbig Reference Hager and Hilbig2020), contemporary research has not squarely addressed the question of how politicians estimate public preferences. Moreover, most theories of representation do not distinguish between incoming and outgoing information. We know that Congressional offices are not equally interested in the opinions of all constituents. Like other political actors, Congressional offices flatten the world, focusing the issues that are most relevant to their desired ends. In this sense, representatives conceptualize constituent opinion primarily as a roadmap to achieving their goal of staying in office (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). For example, in the two years before they are up for re-election, there is evidence that senators are about twice as responsive to shifts in public opinion (Warshaw Reference Warshaw2016). Representatives have an incentive to respond disproportionately to constituencies whose votes, time, and money might help them in their next campaign (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974; Fenno Reference Fenno1977; Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995; Skinner Reference Skinner2007). For instance, Congressional offices are more likely to accept meeting requests—and to schedule higher-level meetings—when constituents requesting the meeting identify as a campaign donor (Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman2016). To get ahead of the electorate, politicians also work to identify constituents’ preferences on electorally salient issues, and avoid taking positions that could provoke an electoral backlash (Arnold Reference Arnold1990). This strategy leads members to follow not only the direction of constituent opinion but also its intensity. Representatives therefore seek out the opinions of engaged constituents who are more likely to notice their policy decisions and hold them accountable (Downs Reference Downs1957; Bawn et al. Reference Bawn, Cohen, Karol, Masket, Noel and Zaller2012).

However, Congressional offices have incomplete information about who potential donors, volunteers, and voters might be. Congressional staff therefore use political activists as a proxy for the people who are most likely to support their campaign in the next election. Constituents who call the Washington office or attend a town hall meeting signal their potential for future involvement in electoral activity (Wright Reference Wright1996). These individuals may then stand in for the preferences of larger groups of constituents. Hence, Congressional offices learn how the public feels about salient issues from constituents who engage in “information-rich” forms of political participation (Griffin and Newman Reference Griffin and Newman2005).

Indeed, prior research shows that staffers are more likely to identify stakeholders on a given bill from subsets of their constituency who donate and contact the office at high rates. Miler (Reference Miler2007) asks legislative staffers in House offices to identify the sub-constituencies in their districts with a stake in each of two specific healthcare reform bills. She finds that staffers are “more likely to see those constituents,” such as physicians, “who contact them and who make financial contributions” (Miler Reference Miler2007, 598, 619). Bartels (Reference Bartels2008) demonstrates that U.S. senators are more likely to respond to constituents who contact them. Further, Leighley and Oser (Reference Leighley and Oser2018) find that non-voting participation predicts congruence in policy preferences between the constituent and their representative at all income levels, suggesting that disproportionate responsiveness to wealthy citizens does not result from affluence alone. And Congressional staff themselves report paying close attention to the most active constituents and incorporating that information in recommendations to members. The vast majority of staffers responding to a Congressional Management Foundation survey said that constituent visits, mail, questions raised at town hall meetings, and “contact from a constituent who represents other constituents” have at least some influence on members who are undecided on the issue in question (CMF 2011).

Interest groups, particularly those with a reputation for representing and persuading electorally influential constituencies, are another important source of information for Congress (Downs Reference Downs1957; Hansen Reference Hansen1991). When they lack information on the priorities and preferences of a particular constituency, members of Congress rely on trusted interest groups to represent this inaccessible group’s views (Herbst Reference Herbst1998; Miler Reference Miler2010; Grossmann Reference Grossmann2012). However, interest groups may not accurately represent public preferences, but instead present a biased picture that aligns with their own interests (Kollman Reference Kollman1998; Jacobs and Shapiro Reference Jacobs and Shapiro2000; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2018; Stokes Reference Stokes2020). As we will argue, this dynamic is compounded when legislative staff engage in targeted outreach to interest groups.

Data and Methods

To understand how Congress learns about constituents’ preferences, we conducted semi-structured interviews with eighteen senior Congressional staff between August and October 2017. These interviews ranged from 20 minutes to 1.5 hours and were conducted either in person—typically in their member’s Washington office—or over the phone. Due to senior staffers’ limited availability, we used a combination of purposive, network, and random sampling to select interviewees. We first reached out to the 101 staffers who had responded to a survey of senior Congressional staff that we had conducted the previous year, expecting these staff would be more receptive to our request. Second, at the end of each interview we asked the subject to refer us to other senior staffers who might be willing to participate. Third, we reached out to a random sample of senior Congressional staff. We randomly selected senior staffers from a list of all chiefs of staff, deputy chiefs of staff, legislative directors, and senior policy advisors for every member of Congress as of July 2016. These efforts yielded a sample of eighteen interviews with thirteen chiefs of staff, four legislative directors, and one senior policy advisor. Eleven respondents worked for Democratic members of Congress, while seven worked for Republicans. In our findings, we both anonymize interviewees’ names and only present information that could not plausibly be used to identify them. To preserve interviewees’ confidentiality, we refer to them only by their title and a letter, and sometimes by whether they work for a member in the House or the Senate.

Our sample of Democratic staff is highly representative of offices in terms of member ideology. The mean DW-NOMINATE score for Democratic offices in our sample is -0.37 (SD = 0.10), compared with an average score of -0.38 (SD = 0.12) among Democratic offices in the 115th Congress. Our sample of Republicans skews more conservative than the caucus writ large during the 115th Congress. The mean DW-NOMINATE score for Republican offices in our sample is 0.63 (SD = 0.33), compared with an average score of 0.49 (SD = 0.15) among Republican offices (McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2006; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Poole, Rosenthal, Boche, Rudkin and Sonnet2020). Our interview sample also skews heavily toward the House of Representatives, with fifteen House and only three Senate staffers. Finally, it is always possible that individuals who agreed to an interview about constituent communication hold systematically different views about this issue than individuals who do not. This is particularly the case among the sample we recruited from staffers who had previously replied to our elite survey. However, our interviews request discussed the role of staff in Congress generally, rather than issues of constituent communication narrowly.

Our sampling strategy targeted the crucial staff connecting constituents with their elected representatives. The chief of staff is the highest-ranking staffer in a Congressional office, presiding over a wide variety of responsibilities. When we asked one chief of staff about his role, he jokingly replied, “Yes, all of them.”Footnote 4 These staffers manage, hire, and supervise staff. They also ensure that the legislative team is advancing the Member’s policy goals, oversee the offices in the district or state, and lead communications. Additionally, and separate from these official roles, many chiefs of staff serve as campaign managers, spearheading their bosses’ fundraising efforts.Footnote 5 Legislative directors have a narrower portfolio but conduct no less important work. They manage a team of legislative assistants seeking to advance the member’s policy priorities by keeping informed on the Congressional agenda, advising the member on votes and co-sponsorship decisions, and developing legislation.Footnote 6 Finally, senior policy advisors—more common in the Senate than in the House—can take on a diverse range of duties depending on the member’s needs. They may focus on a particular legislative area, aid the member’s work on a given committee, or work on projects relating to the constituency.Footnote 7

Our interviews focused on how Congressional offices collect information on constituent opinion, and staffers’ roles in policy decisions. We also explored how staff interpret and convey information about constituent opinion to members of Congress and how the public’s preferences are reflected in policy. We did this using a variant of the grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss Reference Glaser and Strauss1967; Charmaz Reference Charmaz2006). Grounded theory involves analyzing qualitative data through an inductively created list of codes that reflect themes in interviews. We read over each interview transcript, highlighted text relating to one of the codes we had identified, and compiled all relevant evidence for each topic across interviews. In this way, the two main mechanisms of representation we describe in our study—constituent contact and provoked petitioning—were derived inductively.

In conducting these interviews, we were mindful that staffers might have deliberate or unconscious reasons to respond strategically to our questions, including offering responses that cast themselves, their members, or their parties favorably. At the same time, we offered confidentiality to our survey respondents, providing fewer incentives to respond in ways intended to cast them as individuals or their offices in an especially favorable light. Even more importantly, our inductive research design did not depend on testing competing explanations for staffers’ behavior, but rather uncovering from their own thinking an understanding of legislative staff practices. Our sampling strategy also prioritizes senior staff, whose practices may not reflect staff with less experience in Congress.Footnote 8

We supplemented our interviews with a survey of Congressional staff, which we have described and analyzed more comprehensively in other work (Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019). In August 2016, we e-mailed a survey to all senior staff in Congress, including staff with the following titles: Chief of Staff, Deputy Chief of Staff, Legislative Director, and Senior Policy Advisor. Our approach produced a sample of 101 respondents representing 91 offices, resulting in a response rate of 9.6%, similar to other surveys of Congressional staff (CMF 2011). Our sample resembles the general population of senior Congressional staff on various observable characteristics. Staff in Democratic offices are slightly overrepresented in the survey sample, constituting 54% of our sample. Even so, we have enough Republicans in our sample to conduct disaggregated analyses by party. Importantly, the offices for which our respondents worked were representative of Congress more broadly in terms of ideology, as indicated by DW-NOMINATE scores (Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Lewis, Lo, McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2015; Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019).

Representatives Respond and Provoke: How Congressional Offices Estimate Constituent Opinion

Understanding constituent opinion is central to Congressional offices’ work. Almost half of Hill offices have reported diverting resources from other functions toward keeping track of constituent correspondence (CMF 2011). In our survey, we asked staffers to identify their most important considerations when advising on legislative decisions. As figure 1 shows, staffers on both sides of the aisle report that constituent opinion and communications are paramount. Compared to any other input, the largest number of senior Congressional staffers reported these as an important consideration when advising the member on legislative decisions.

Figure 1 Staff considerations when advising member.

Figure 1 displays the results from the following question: “Think about the policy proposals you have worked on during your time on the Hill. What shaped your thinking on whether your member should support or oppose these policies? Indicate how important each of the following considerations was in shaping your advice to your member on various policy proposals.” Response options included “Not all that important,” “Slightly important,” “Moderately important,” “Very important,” and “Extremely important.” The dark grey bars represent the percentage of Democratic staffers indicating that a given consideration was at least “Very important,” while the light grey bars indicate the percentage of Republican staffers providing this response.

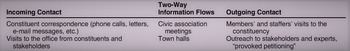

Offices are far more concerned with opinion in the member’s constituency than with national public opinion. Consistent with Fenno’s (Reference Fenno1977) concept of the “geographic constituency,” staff universally defined a constituent as a resident of the member’s district or state. Only 20% of Democratic staffers and 33% of Republican staffers reported that national public opinion was an important consideration when advising the member. In contrast, 76% of Democratic staffers and 86% of Republican staffers said that public opinion in their constituency was important. Our surveys and interviews also indicated that constituent opinion information flows from the bottom up—from constituents to the offices—and from the top down—with offices eliciting information from constituents (table 1). The next sections describe these two practices in turn.

Table 1 Common methods for learning about constituent opinion

How Congressional Offices Receive, Organize, and Respond to Constituent Contact

To represent the interests of their constituents, Congressional offices must constantly gather incoming information to evaluate public preferences. However, constituencies are complex. As Fenno (Reference Fenno1977) argues, members of Congress do not see their constituencies as an “undifferentiated glob.” Districts and states comprise a host of demographic groups, interest groups, voters and non-voters, co-partisans, and supporters of other parties. How do offices isolate a meaningful signal from this noise?

In their efforts to make their constituencies legible for electoral purposes, Congressional offices rely on some tools more than others. Perhaps surprisingly, given their near-constant presence in the media, Congressional offices reported in interviews that they rarely polled their constituents on specific issues or estimated constituency-level opinion from national surveys. A few staffers noted that they occasionally conducted representative opinion polls, but not with the regularity necessary to maintain up-to-date public opinion estimates.Footnote 9 One chief of staff expressed that it would be ideal to conduct surveys to measure the opinions of a representative sample of their constituency, but that their office lacked the resources.Footnote 10 Moreover, recent work suggests that staffers are disinterested in polling results even when they are available (Kalla and Porter Reference Kalla and Porter2020).

Instead, constituent correspondence is a central source of public opinion data for Congress. Offices keep track of constituent phone calls, e-mails, and letters in a database. Virtually all use software from Lockheed Martin, Fireside21, or IQ—three private-sector companies specializing in constituent relationship management platforms—to record and compile correspondence from constituents, sometimes merged with information from other public and commercial sources, including voter files (Hersh Reference Hersh2015; Emerling et al. Reference Emerling, Bibens, Bond and Caldwell2017).Footnote 11 These software platforms emerged in the 1990s and have become more sophisticated over time.

Staffers enter e-mail messages, letters, and phone calls into these systems,Footnote 12 and many offices use contact information to screen out correspondents who are not constituents.Footnote 13 Some staffers we interviewed also reported that their office uses the database to record the names of constituents who have attended town hall meetings or other public events.Footnote 14 The software allows correspondence to be labeled by topic and direction. Many offices aggregate correspondence within issue areas to calculate total volume and relative amount of supportive and opponent contact the office has received on an issue over a given time period.Footnote 15

After coding their data, staffers use these databases to construct images of their constituents’ preferences. They query their databases to understand which issues are salient and to measure the balance of opinion. The latter practice is very common before a vote on a bill or a speech on that topic. While most successful legislation is still bipartisan, many votes fall along party lines (Curry and Lee Reference Curry and Lee2019).Footnote 16 Yet constituent opinion can influence members’ decisions, including where to invest their scarce legislative time and energy. Constituent correspondence can help set the Congressional agenda for politicians, suggesting issues to elevate, which bills to co-sponsor, and how to vote on legislation that cuts across party lines.Footnote 17

Our staffer survey also provides evidence that constituent correspondence can have a clear effect on the legislative process. We asked staffers to imagine that their office was considering a bill under debate in Congress, and had received letters expressing opinions on the bill. We provided respondents information on these letters, randomly assigning respondents to different conditions. The survey question read as follows, with the different treatments shown in square brackets:

Imagine your office is considering a bill that is under debate in Congress.

-

• Your office receives [2/20/200] letters from constituents [supporting/opposing] this bill.

-

• The letters have very [similar/different] wording to one another.

-

• The letter writers identify themselves as [constituents/employees of a large company based in your constituency/members of a non-profit citizens group].

Respondents reported, on a four-point scale, how likely they would be to mention these letters to the member, how significant these letters would be in their advice to the member on the bill, and how representative of their constituents they would consider the letters to be. Given our small sample, we pool our analysis across treatment conditions, that is, comparing levels within each of the three treatment conditions rather than each condition individually.Footnote 18 (For instance, we compare the difference between an office receiving 2, 20, or 200 letters, pooling across all other treatment conditions.)

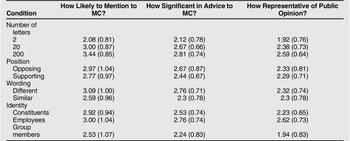

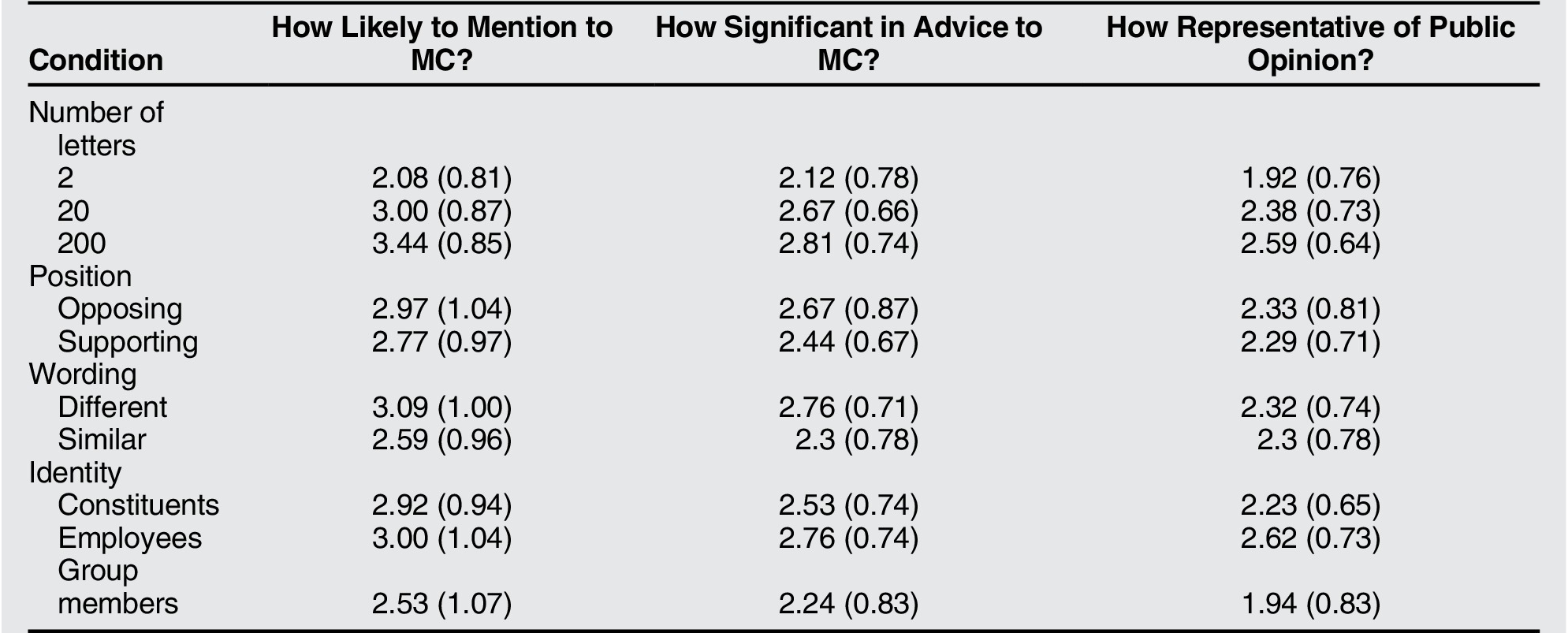

Nearly two-thirds of staffers said they would be at least somewhat likely to mention relevant letters to the member when advising them on a bill, and more than half said these letters would be at least somewhat significant to their advice. However, while our interviews indicate that members’ co-sponsorships and legislative priorities sometimes arise from constituent correspondence—particularly when policies impose visible and salient costs on constituents—staffers generally do not consider such correspondence to be representative. Footnote 19 Across all treatment conditions, only about four in ten respondents said that they would consider the letters to be at least somewhat representative of constituents. These results underscore that staffers recognize that their methods of constituent opinion estimation are systematically biased toward particular subsets of their constituencies. We summarize the full results of the experiment in table 2.

Table 2 Constituent communication experiment

Notes: The table summarizes the mean and standard deviation (in parentheses) for each treatment condition in the survey experiment, with responses ranging from one to four (with greater values indicating greater likelihood, significance, and representativeness).

We find that the volume of letters, the wording of the letters, and the identities of the letter-writers all impacted staffers’ reported actions. The volume of letter-writers affected the likelihood that staffers would mention the letters to the member. On a four-point scale, staffers receiving twenty letters were nearly one point (0.92) more likely to mention the letters than staffers receiving only two letters (SE = 0.23, p < 0.01). Staffers receiving two hundred letters were 0.44 points more likely to mention the letters than staffers receiving twenty letters (SE = 0.23, p < 0.1). Second, higher correspondence volume increased the significance of the letters in staffers’ advice to the member. On a four-point scale, staffers receiving twenty letters considered the letters 0.55 points more significant than staffers receiving only two letters (SE = 0.19, p < 0.01). However, we do not find a statistically significant difference in the significance of the letters between staffers receiving twenty and two hundred letters (DIM = 0.15, SE = 0.19, p = 0.43). Third, the more letters staffers receive, the more they consider them representative of constituent opinion—up to a point. On a four-point scale, staffers receiving twenty letters considered the letters 0.46 points more representative than receiving only two letters (SE = 0.20, p < 0.05). However, we do not find a statistically significant difference in perceptions of representativeness between staffers receiving twenty and two hundred letters (DIM = 0.21, SE = 0.18, p = 0.25).

Our experiment also demonstrates that staffers systematically discount similarly worded letters, which may signal an advocacy campaign involving little effort on the part of the letter-writers. We do not find evidence that staffers perceive similarly worded letters as less representative of the constituency (DIM = -0.02, SE = 0.17, p = 0.90). However, they are less likely to mention similarly worded letters to the member, and these letters are less significant in their advice. Staffers receiving similarly worded letters are 0.49 points less likely to mention them (SE = 0.22, p < 0.05), and deem the letters 0.46 points less significant (SE = 0.16, p < 0.01).

Our interview data confirm that staffers disregard messages from online advocacy campaigns, considering them unrepresentative of constituents’ views.Footnote 20 Staffers pay little heed to pre-written form emails. One chief of staff recalled that his office once responded to a constituent’s message only for the constituent to reply that they had never contacted the office; apparently, the constituent had forgotten they had signed their name on a form e-mail.Footnote 21 In the House, mass online mailings from advocacy groups arrive through a system called Communicating with Congress. This system, which was developed in conjunction with the Congressional Management Foundation, brings contact from advocacy campaigns into office databases via a separate channel. The inspiration was a unified system through which advocacy campaign mailings could be sorted by office. However, having a separate channel may unintentionally allow offices to discount form letters from advocacy campaigns.

By contrast, Congressional offices pay more attention when they perceive a substantial number of constituents putting a significant investment of time and energy into a given issue. A few of our interviewees mentioned that their offices seek to understand their voters’ priorities by identifying the issues constituents have organized around.Footnote 22 One legislative director said that he could tell a particular issue was important to constituents based on the amount of groups in the district working on the issue, and the level of constituent activism, including fly-ins to lobby the member on Capitol Hill.Footnote 23 Some staffers we interviewed also mentioned that they take note of issues people ask questions about at town halls and civic association meetings.Footnote 24

Hence, current practices within Congressional offices do not focus on tracking constituents’ general policy mood, as previous scholarship has proposed (Erikson, MacKuen, and Stimson Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002). Instead, offices track constituent opinion on specific issues. Offices also give more weight to contact that takes more resources—expressing an opinion on a specific issue, showing up to town halls or member’s offices, calling or writing independently—all practices that are easier for affluent and well-organized constituents (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012). While constituents’ views on salient issues can help inform staffers’ advice to their member, our evidence suggests that organized groups’ views are more commonly factored into legislative decisions. One of the first steps legislative staff take when preparing advice is to “spend time figuring out who the stakeholders are” to identify their positions on the proposal.Footnote 25 When advising the member on votes and co-sponsorships, it is common practice for staff to mention interest groups’ positions on the legislation in question.Footnote 26

Results from our survey similarly suggest that interest groups play an important role in shaping staffers’ recommendations. We presented staffers with a list of national interest groups and asked how important these groups’ positions, resources, and information were when considering legislation. Groups identified as “very important” by at least a quarter of staffers included, for Republicans: the NRA, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, the Heritage Foundation, and the Club for Growth; and for Democrats: the AFL-CIO, the League of Conservation Voters, the Center for American Progress, the Sierra Club, and Everytown for Gun Safety. When we asked staff to identify the groups other offices mentioned when trying to persuade their member to vote a certain way on a bill, economic interest groups figured prominently in staffers’ responses, including the Chamber of Commerce, the AFL-CIO, and the National Association of Manufacturers. Overall, offices develop significant relationships with interest groups across a range of policy issues.

Interest groups have also developed new tactics to strengthen their influence in Congress. Businesses recognize that constituent contact figures prominently in Congressional offices’ perceptions of public opinion. Hence they often mobilize their employees or other grassroots constituencies (like customers or suppliers) to reach out to their representatives (Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2018; Walker Reference Walker2009; Stokes Reference Stokes2020). Among other forms of contact from businesses, we asked respondents how useful they would find correspondence from a business’s employees when deliberating over legislation. Respondents could indicate whether a given form of contact was not at all, slightly, moderately, very, or extremely useful (figure 2).Footnote 27 Around a third of staffers considered correspondence from a business’s employees to be very or extremely useful. In our prior research, we found that Congressional staff consider letters from employees of a large business in the member’s constituency to be more representative of constituent opinion than letters from self-identified constituents or members of a citizen group (Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger, and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019). The weight Congressional staff assign to letters from employees is striking. Just as the mechanisms of representation amplify the voices of politically engaged individuals, they also give interest groups’ demands greater resonance within the policymaking process. In the next section, we describe how Congressional offices proactively invite interest groups and other stakeholders to weigh in on legislative decisions.

Figure 2 Usefulness of business contact strategies for legislative advice.

The figure displays responses to the following question: “Businesses often contact Congressional offices to support or oppose policy proposals. Thinking about the ways that businesses have contacted your office about policy proposals in the past year, which strategies have been most useful to your office as you deliberate over legislation?” Respondents could indicate that such strategies were “Not at all useful,” “Slightly useful,” “Moderately useful,” “Very useful,” or “Extremely useful.” The dark grey bars represent the percentage of Democratic staffers reporting that a particular strategy was at least “Very useful,” while the light grey bars indicate the percentage of Republican staffers providing this response.

Provoked Petitioning: How Congressional Offices Reach Out to Stakeholders

Standard accounts of lobbying and constituent representation suggest a one-way relationship: interest groups and constituents request meetings with legislators or their staff to influence member behavior on legislation.Footnote 28 However, our interviews emphasize that lobbying is a two-way street: staff also acquire information on constituent opinion by proactively reaching out to key constituencies. In part, Congressional offices reach out because they hear little to nothing from constituents on many issues.Footnote 29 Staff recognize that this silence does necessarily represent the level of public engagement; as one chief of staff asserted, “If we haven’t heard from people, it may not indicate a lack of interest.”Footnote 30

To address this information shortfall, senior Congressional aides often rely on an outgoing method of information-gathering which we call “provoked petitioning.” This practice involves reaching out to constituents—often members or representatives of organized groups—for information on key constituencies’ priorities, preferences, and problems. First, offices seek to identify constituents’ priorities—the issues that are most likely to matter come election season. Second, offices seek to learn constituents’ preferences on specific, salient issues or individual pieces of legislation. Third, offices seek to gather information about the problems on the legislative agenda. As one chief of staff put it, an office will conduct outreach to answer the following questions: “Have you heard of this?”, “How important is it?”, and “Do you have a view on this?”Footnote 31

To identify constituents’ priorities, offices dispatch staff to meetings and events in the district to engage with politically active constituents. District staff regularly attend the meetings of civic associations such as rotary clubs, county boards of supervisors, and local chambers of commerce.Footnote 32 It is also common practice for many members to hold town hall meetings with constituents, either in person or remotely (Bradner Reference Bradner2017).Footnote 33 One chief of staff described a public event in the constituency involving a panel of speakers on an issue of interest to constituents, noting that the district staff would record the questions that constituents raised. Although he remarked that the attendees represented a small sample of the member’s constituents, he reasoned that they “took time out of their day” to participate, implying that their questions are worthy of special consideration.Footnote 34 Another chief of staff agreed, asserting that there is a relatively small group of “civically active” constituents who attend various kinds of public meetings. While acknowledging that these people are not representative of the constituency, he posited that these constituents are “relied upon to give information” about politics to their neighbors, and therefore “maybe they’re more important than the other 719,000 people.” After attending these meetings, staffers report to the member the issues that constituents are talking about.Footnote 35 In this way, politically active constituents’ priorities stand in for the priorities of voters writ large. Creative members looking for even more opportunities to elicit constituent opinion supplement town halls with other formats such as mobile district office hours, in which the member sets up a temporary office in their constituency, inviting constituents to present casework or proposals for legislation.Footnote 36

Provoked petitioning can also inform offices about constituents’ preferences on salient issues.Footnote 37 One legislative director described a time when a letter from a constituent voiced concern about a change in a federal law. A staffer was assigned to reach out to people—even beyond the member’s district—and learned that there was a “growing constituency nationwide that didn’t like the change that had been made.” As a result of staffers’ meetings with constituents opposed to the change, the member introduced a bill to undo it. Similarly, when his office decided to develop legislation that would affect a particular industry, he started by reaching out to firms within the industry for their opinions on the kind of legislation that could be introduced.Footnote 38 Provoked petitioning also helps offices learn constituents’ positions, alleviate their concerns, and ensure that they are satisfied with the member’s performance. One chief of staff explained that he tries “to expose [the member] to both sides of [an] issue so he can hear from the stakeholders themselves what their position is.”Footnote 39 Staffers may also reach out to groups when the Member plans to vote for a bill that an influential group opposes, but wants to “let them know that we’re thinking about them.”Footnote 40

Finally, Congressional offices reach out to people and organizations that they consider to have expertise on the problems on the legislative agenda. Legislative staff specializing in a given area frequently seek out reports on the issue in question from interest groups and think tanks.Footnote 41 One chief of staff noted that her boss would call or visit the authors of studies addressing the topic of the legislation he was developing.Footnote 42 Just as Congressional offices specifically seek to learn the opinions of their constituents, they seek to understand how policy proposals would affect their district or state.Footnote 43

How do offices determine that a constituency is sufficiently important to conduct provoked petitioning? Constituents who stand to be affected by a policy loom large in Congressional staffers’ mental models of their districts and states. Staffers used the term “stakeholder” in our interviews with sufficient regularity to suggest that it represents a common shorthand on Capitol Hill. The term “stakeholder” is often used to refer to an interest group, but the definition is broader than this. One chief of staff offered perhaps the most precise definition when he mentioned that his office seeks to consult people “who are actually living under the law.”Footnote 44 A stakeholder is a constituency, or a member or representative of that group, which stands to gain or lose from a given policy or proposal. A stakeholder can be an interest group, a government official, a public employee, a business owner, a member of a civic association, or simply a constituent who believes that a policy may affect them.

These stakeholders are central to Congress’s decision-making process. One chief of staff described a process of consulting various sources to prepare a vote recommendation on an education bill. A staffer might speak with teachers’ unions and school advocates, as well as school administrators or the state government.Footnote 45 A legislative director recounted a time when their member was approached to sponsor legislation affecting a particular industry. After listening to the organization supporting the bill, the office sought to identify the range of stakeholders. The legislative staff met with industry groups, reached out to several relevant organizations in the member’s state, and wrote a memo for the member explaining which stakeholders were in favor of the bill and which were opposed.Footnote 46 Importantly, many of these contacts were solicited; in these cases, the office, rather than the stakeholder, took the initiative.Footnote 47 Thus, the process of gathering constituent opinion information gives stakeholders disproportionate influence relative to the average constituent.

Over time, staffers build a network of relationships with stakeholders who they can consult when they want to better understand particular issues or constituencies.Footnote 48 Multiple chiefs of staff used a form of the word “trust” when describing the groups or individuals to whom they reach out when preparing to advise the member on a given issue.Footnote 49 Not only do those who gain this trust acquire the ability to access Congressional offices, these offices come to rely on them for political intelligence. Staffers reach out to advocates that they “know and work with.”Footnote 50 Staffers turn to these stakeholders when they lack information about the potential reception of a policy proposal among the constituency which the stakeholder represents. One chief of staff reported that the member would ask the legislative director to describe stakeholders’ positions on legislation prior to voting.Footnote 51 Another mentioned that every time the member seeks to introduce legislation, his office will reach out to stakeholders for their views.Footnote 52

While provoked petitioning can involve national interest groups, Congressional offices often rely on stakeholders based in the member’s district or state. Members and their staff often visit businesses on their trips home, asking the company’s leaders how policies would affect them.Footnote 53 Further, field representatives in the district or state offices are tasked with interacting regularly with organizations based in the constituency such as local chambers of commerce, service groups, trade associations, businesses (especially large employers), and labor unions. One chief of staff described it this way:

[We have a] regular channel of communication between the field representatives and the D.C. office … [A field representative may be] out meeting with this pharmaceutical company, and they’re concerned about this [regulation that is] about to be sent out for comment, and when they hear that they’ll make sure that the person in D.C. who has that issue area is informed about what’s going on, and [the staff in D.C. will] work with the folks back in the state to make sure they’re fully informed of [their] concerns.Footnote 54

Contact with stakeholders in the district or state allows Congressional offices to ensure that the advice they receive from national interest groups does not conflict with their constituency’s interests. One chief of staff noted that his office reaches out to firms in the member’s state to ensure that national-level trade associations are taking positions in line with state-level firms, to ensure their “concerns are addressed in whatever piece of legislation that we’re working on.”Footnote 55 Conversely, when constituency-based stakeholders lack a position, staffers tend to consult national interest groups who are more engaged on the issue.Footnote 56 Provoked petitioning thus allows staffers to ensure that their advice to the member reflects the positions of organized groups with a stake in the proposal.

Of course, provoked petitioning is not the only, or even the most frequent, way in which Congressional offices reach out to constituents. Offices also proactively attempt to shape opinions and demonstrate how the member is responding to constituents (Grimmer, Westwood, and Messing Reference Grimmer, Westwood and Messing2015). Relying on their correspondence databases, Congressional staff—typically, legislative assistants and legislative correspondents—identify the issues on which they are hearing a great deal from constituents. Once staff determine that an issue is highly salient, they begin sorting relevant correspondence into a “batch” within the correspondence database.Footnote 57 Staff then write a response to the constituents who contacted the office about the issue, typically outlining the member’s position and action on the issue in question.Footnote 58 One legislative director added that for key constituencies, the office will “find something to e-mail them about” to maintain contact on a regular basis.Footnote 59 Thus, Congressional offices do not merely respond to their constituents’ preferences; they proactively shape the priorities and preferences of issue publics within their constituency, helping to bring certain interests into being (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967; Disch Reference Disch2012; Lenz Reference Lenz2012).

Conducting the Heavenly Chorus

Describing Washington in the mid-twentieth century, Schattschneider famously wrote that the “heavenly chorus sings with a strong upper-class accent.” Subsequent research has shown that this problem persists. Disparities in economic resources, including along racial lines, have helped interest groups exert undue influence over government officials (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2018). However, as Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) observed during Schattschneider’s era, politicians do not merely respond to their constituencies. By invoking particular groups and interests, elected officials help bring these constituencies into being (Disch Reference Disch2012).

In this paper, we have explored how Congressional offices both assemble and conduct the heavenly chorus—helping to bring out its distinctly upper-class accent. While Congressional offices respond to contact from constituents—both individuals and organized groups—they also frequently elicit such contact to learn constituents’ views, a practice we describe as “provoked petitioning.” If constituent correspondence privileges the affluent and organized because they are closer to the microphone, provoked petitioning amplifies this bias by handing interest groups a megaphone.

Despite the proliferation of instruments for estimating constituent opinion, such as downscaled national opinion polling, Congressional offices tend to rely on tools that perpetuate old biases. Offices process and organize constituent correspondence to identify salient issues and estimate the prevailing opinion on these issues among politically engaged constituents based on the volume of contact and its direction. They supplement this information with advice from organized groups. In the frequent cases when offices’ demand for information exceeds their supply, they reach out to stakeholders on a given bill or issue to learn. Staffers develop networks of relationships with trusted groups perceived to have a vested interest in the issues of the day, and rely on them for guidance in developing legislation, casting votes, and co-sponsoring legislation. They consequently rely on interest groups and politically active constituents to stand in for the opinions of their constituents writ large.

Of course, information about constituent opinion accounts for only some of the members’ behavior regarding votes, co-sponsorships, and where to invest scarce legislative resources. Staffers’ recommendations on legislation also incorporate a series of factors beyond constituent opinion, including party agendas, policy analysis, economic impacts on their district or state, consistency with prior votes, other members’ positions, and the president’s position.Footnote 60 Further, members make many legislative decisions independently of their staffs. Lawmakers often lobby each other directly to co-sponsor, take action, or vote a certain way on legislation.Footnote 61 Many co-sponsorships also originate from other offices reaching out to a member’s legislative staff.Footnote 62 In these situations, staffers’ recommendations—and the knowledge that informs them—play an important role.

Our findings shed light on several major and interrelated developments in contemporary American politics: economic inequality, systemic racism, and partisan polarization. First, politically active constituents are disproportionately affluent and well organized, and groups with few resources are unlikely to organize and participate in politics (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012, 123, 280). When less affluent constituents voice their concerns to public officials, they are more likely than their wealthier counterparts to call attention to “issues of basic human need” such as poverty and jobs (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012). If offices listen primarily to active constituents and interest groups, this may contribute to representatives’ disproportionate responsiveness to the wealthy (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1975; Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014). Because non-Hispanic whites comprise a disproportionate share of affluent Americans, the messages representatives hear from constituents are likely also distorted along the dimension of race.

Not only is the average political participant unrepresentative in terms of race and class, politically active constituents also tend to have more extreme or intense preferences. Strong partisans and those with homogeneous political discussion networks are especially likely to participate in politics (Mutz Reference Mutz2006, 123; Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993, 155), and the ideological gap is widening between Republican and Democratic “activists” and other citizens (Jacobson Reference Jacobson, Bond and Fleisher2000). In addition to strong partisans, people with personal commitments to policy outcomes (e.g., Social Security recipients) are more likely to participate (Campbell Reference Campbell2003; Han Reference Han2009). We might expect that these people are likely to hold intense preferences and unlikely to favor compromise. Due to their focus on the most politically active constituents, Congressional offices may perceive the public to be more polarized than it is in practice (Fiorina, Abrams, and Pope Reference Fiorina, Abrams and Pope2011). In turn, this perception might help explain why both Democratic and Republican members of Congress are more ideologically extreme than their constituents (Bafumi and Herron Reference Bafumi and Herron2010).

We are not advocating a radical change in Congressional staffers’ methods of tracking public opinion. Given the electoral incentives and resource constraints that Congressional offices face, in the near term such changes are unrealistic (Furnas et al. Reference Furnas, Drutman, Hertel-Fernandez, LaPira, Kosar, LaPira, Drutman and Kosar2020; LaPira, Drutman, and Kosar Reference LaPira, Drutman and Kosar2020). Meanwhile, as public opinion researchers have documented, polls have many problems of their own—question wording and order effects, non-response bias, and social desirability bias, to name a few (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2005; Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016). And there are normative reasons to give greater weight to the views of participants who are most vocal, as these participants might have the most at stake in a policy debate. As the case of the civil rights or LGBT rights campaigns illustrate, majority public opinion can lag behind movements pushing for urgent social change (Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1992). Still, our results point towards important questions for scholars of representation. Surveys should include a more diverse range of questions to elicit more information about the patterns and scope of provoked petitioning. This work will allow for clearer statements about the generalizability and representativeness of the findings we discuss in this paper. At the same time, scholars should also work towards surveying local interest groups, businesses and targeted constituents to understand how these actors engage with communications from their representative. Once we recognize that the dynamics of representation occur in two directions, important new empirical avenues become apparent.

More broadly, what is necessary is the reconstitution of civic infrastructure. The decline in mass-membership-based organizations representing lower- and middle-class Americans has diminished the political voice those Americans command (Putnam Reference Putnam2000; Skocpol Reference Skocpol2003; Feigenbaum, Hertel-Fernandez, and Williamson Reference Feigenbaum, Hertel-Fernandez and Williamson2018). Research has shown that civic associations, such as community organizations and labor unions, can boost the political participation of otherwise unlikely citizens (Skocpol Reference Skocpol2003; Osterman Reference Osterman2006; Han Reference Han2009). For all constituents’ opinions to inform legislative decisions and actions, we need a stronger array of intermediary organizations that can ensure that Americans have the opportunity to voice their views to their elected officials.

Acknowledgements

The Dirksen Congressional Center provided funding for the project through its Congressional Research Grant program.