Introduction

Chiroptera is one of the most speciose, diverse and widespread mammalian orders worldwide, with nearly 1450 species (Simmons and Cirranelo, Reference Simmons and Cirranelo2022). Particularly, in the Neotropical zone 450 species have been recorded (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Solari, Gregorin, Aguirre and Barquez2021). Despite this high diversity, the study of helminth communities of this host group is relatively rare compared to those of other wild mammals (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Parker, Parker and Brooks2012). The most recent gathering of information on the helminth–bat association carried out in the Neotropical zone confirms this assertion: the number of helminth taxa registered in 27 species of bats analysed in Mexico and Central America is 68 (Jiménez et al., Reference Jiménez, Caspeta-Mandujano, Ramírez-Chávez, Ramírez-Díaz, Juárez-Urbina, Peralta-Ramírez and Guerrero2017), while in South American bats, Santos and Gibson (Reference Santos and Gibson2015) reported 114 nominal species of helminths from 92 named bat taxa.

In Mexico, studies on bat helminths began in the late 1930s (Chitwood, Reference Chitwood1938; Stunkard, Reference Stunkard1938), totalizing 53 helminth species recorded to date (Jiménez et al., Reference Jiménez, Caspeta-Mandujano, Ramírez-Chávez, Ramírez-Díaz, Juárez-Urbina, Peralta-Ramírez and Guerrero2017; Salinas-Ramos et al., Reference Salinas-Ramos, Herrera, Hernández-Mena, Osorio-Sarabia and León-Règagnon2017; Luviano-Hernández et al., Reference Luviano-Hernández, Tafolla-Venegas, Meléndez-Herrera and Fuentes-Farías2018; Panti-May et al., Reference Panti-May, Hernández-Mena, Torres-Castro, Estrella-Martínez, Lugo-Caballero, Vidal-Martínez and Hernández-Betancourt2021). On the other hand, the number of bats surveyed for helminths in the country represents roughly 14% of the richness of chiropterans present (Jiménez et al., Reference Jiménez, Caspeta-Mandujano, Ramírez-Chávez, Ramírez-Díaz, Juárez-Urbina, Peralta-Ramírez and Guerrero2017). Particularly, in the Yucatan Peninsula (formed by the Mexican states of Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo) 64 species of bats are distributed, which are included in 7 families (Sosa-Escalante et al., Reference Sosa-Escalante, Pech-Canché, Macswiney and Hernández-Betancourt2013, Reference Sosa-Escalante, Hernández-Betancourt, Pech-Canche, MacSwiney and Díaz-Gamboa2014). However, only 11 helminth taxa have been reported in Yucatan and 3 in Campeche from 6 bat species (Jiménez et al., Reference Jiménez, Caspeta-Mandujano, Ramírez-Chávez, Ramírez-Díaz, Juárez-Urbina, Peralta-Ramírez and Guerrero2017; Panti-May et al., Reference Panti-May, Hernández-Mena, Torres-Castro, Estrella-Martínez, Lugo-Caballero, Vidal-Martínez and Hernández-Betancourt2021). The remaining 58 bat species have not been studied from a helminthological perspective.

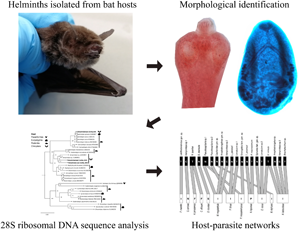

The majority of data on helminths of bats in Mexico come from checklists of species, new species descriptions and new hosts or locality records based on morphological identifications, whereas molecular characterization is limited to the work of Panti-May et al. (Reference Panti-May, Hernández-Mena, Torres-Castro, Estrella-Martínez, Lugo-Caballero, Vidal-Martínez and Hernández-Betancourt2021). Worldwide completeness is uncommon in host–helminth inventories (Poulin and Presswell, Reference Poulin and Presswell2016). To accelerate the rate of description of helminth biodiversity, an integrative taxonomy approach combining traditional morphological description and modern molecular genetics is necessary to characterize helminth species (Poulin and Presswell, Reference Poulin and Presswell2016; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Hay and Jorge2019). The increased availability of gene sequences of helminths in the last 2 decades has also proven essential for progress in resolving several crucial elements towards a clear understanding of the process of host–parasite coevolution, such as parasite phylogeny, cryptic parasite diversity and gene flow among parasite populations (Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Hay and Jorge2019).

In addition to the integrative taxonomy, carrying out ecological studies in the host populations, such as network analysis, will allow determining some factors associated with the transmission of parasites between hosts (Luis et al., Reference Luis, O'Shea, Hayman, Wood, Cunningham, Gilbert, Mills and Webb2015; Runghen et al., Reference Runghen, Poulin, Monlleó-Borrull and Llopis-Belenguer2021); this, in turn, will provide information on the potential hosts for some helminth groups. Certain ecological attributes of hosts (locomotion, diet, activity period, etc.) and parasites (type of life cycle) would increase their chance of acquiring parasite infections; however, the number of possible host–parasite interactions may be limited by phylogeny to a subset of species with a shared co-evolutionary history (Poulin, Reference Poulin2010; Pilosof et al., Reference Pilosof, Morand, Krasnov and Nunn2015). Therefore, to understand the ecology and evolution of both parasites and their hosts, it is important to realize ecological studies at different levels (individual, populations and communities), in which the patterns of interaction between hosts and parasites are evaluated (Bellay et al., Reference Bellay, Oda, Campião, Dáttil and Rico-Gray2018; Paladsing et al., Reference Paladsing, Boonsri, Saesim, Changsap, Thaenkham, Kosoltanapiwat, Sonthayanon, Ribas, Morand and Chaisiri2020). In this context, the objective of the present study was divided into several folds: (1) to establish the helminth fauna of bats using an integrative taxonomy approach (morphological characters and phylogenetic analysis); (2) to characterize their infection levels and (3) to explore the helminth–bat interactions through network analysis in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico.

Materials and methods

Collection and examination of bats

Bats were collected from 2017 to 2022 in 15 sites throughout the Yucatan Peninsula (Fig. 1), including cattle ranches, natural parks and ecotourism hotels under permits from the Mexican Ministry of Environment (SGPA/DGVS/03705/17, SGPA/DGVS/001643/18, SGPA/DGVS/05995/19, SGPA/DGVS/00786/21 and 31/K5-0032/02/22). In each collection site, 1 or 2 mist nests (12 m wide × 2.5 m high) were placed close to vegetation, natural ponds, animal pens or cave entrances, for 1–2 nights (Table 1). The captured bats were removed from the nets, placed in cloth bags and identified using the field guide of Medellín et al. (Reference Medellín, Harita and Sánchez2008). Animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by overdose of sodium pentobarbital. The heart, lungs, stomach, liver, intestines and mesenteries of each specimen were collected and stored in 96% ethanol.

Fig. 1. Location of the sites (black triangles) where bats were captured in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico.

Table 1. Sample sites of bats examined in this study

The infected hosts were deposited in the Colección Zoológica (CZ), Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Catalogue numbers are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Collection and morphological identification of helminths

All collected organs were dissected from each bat and immersed in distilled water in Petri dishes using a stereo microscope (Olympus SZ2-ILST). Helminths were collected, counted and preserved in 70% ethanol until definitive morphological and molecular identification. For morphological characterizations, nematodes were cleared and temporarily mounted in lactophenol; platyhelminths were stained with carmine acid, dehydrated through an ethanol series, cleared in methyl salicylate and mounted permanently in Canada balsam. Specimens were studied under light microscopy (Leica DM500). Morphological features were used to identify helminths at different taxonomic levels (e.g. order, family and genus), using keys for nematodes (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Chabaud and Willmott2009), cestodes (Khalil et al., Reference Khalil, Jones and Bray1994) and trematodes (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Bray and Gibson2005; Bray et al., Reference Bray, Gibson and Jones2008), as well as specialized literature on helminths of bats (e.g. Falcón-Ordaz et al., Reference Falcón-Ordaz, Guzmán-Cornejo, García-Prieto and Gardner2006; Caspeta-Mandujano et al., Reference Caspeta-Mandujano, Peralta-Rodríguez, Ramírez-Díaz and Tapia-Osorio2017). Helminth voucher specimens were deposited in the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (CNHE), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Catalogue numbers are included in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence and mean intensity of infection for each helminth taxon were estimated according to Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997) and calculated using Quantitative Parasitology 3.0 software (Rózsa et al., Reference Rózsa, Reiczigel and Majoros2000). The 95% confidence intervals for both parameters were calculated (Rózsa et al., Reference Rózsa, Reiczigel and Majoros2000; Reiczigel, Reference Reiczigel2003).

DNA extraction and sequencing of helminths

Total genomic DNA of some helminths was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. The 28S gene of ribosomal DNA was amplified and sequenced using a conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the forward primer 391 5′-AGCGGAGGAAAAGAAACTAA-3′ (Stock et al., Reference Stock, Campbell and Nadler2001) and the reverse primer 536 5′-CAGCTATCCTGAGGGAAAC-3′ (Stock et al., Reference Stock, Campbell and Nadler2001), which amplify a fragment of 1400 base pairs. These fragments were amplified using PCR protocols and thermal profiles previously described (Hernández-Mena et al., Reference Hernández-Mena, García-Varela and Pérez-Ponce de León2017; Panti-May et al., Reference Panti-May, Hernández-Mena, Torres-Castro, Estrella-Martínez, Lugo-Caballero, Vidal-Martínez and Hernández-Betancourt2021).

28S PCR products were sequenced (Laboratorio de Secuenciación Genómica de la Biodiversidad y de la Salud, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico) with the previously used primers (391 and 536) and the following internal primers: 503 5′-CCTTGGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACG-3′ (García-Varela and Nadler, Reference García-Varela and Nadler2005) and 504 5′-CGTCTTGAAACACGGACTAAGG-3′ (Stock et al., Reference Stock, Campbell and Nadler2001). The resulting sequences were analysed and edited in Geneious Pro 4.8.4 software (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) and a consensus was obtained for each sequenced specimen. Sequences generated in this study were submitted to GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information). Accession numbers are given in Supplementary Table S3.

Phylogenetic analysis

To corroborate the identification and genealogical relationships of the parasites, phylogenetic analyses were performed with the new DNA sequences. The alignments of the sequences were generated with ClustalW (http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw/) using the approach ‘SLOW/ACCURATE’ and weight matrix ‘CLUSTALW (for DNA)’ (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Higgins and Gibson1994). The nucleotide substitution model was estimated for each dataset with jModelTest v2 (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Taboada, Doallo and Posada2012). The phylogenetic analyses were performed with the maximum-likelihood method (ML) in RAxML v. 7.0.4, and executed with 1000 bootstrap repetitions to obtain the best phylogenetic tree of each dataset (Stamatakis, Reference Stamatakis2006). The trees were visualized and edited in FigTree v. 1.4.4. The molecular variation of 28S datasets was calculated using P-distances with software MEGA v6 (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher, Peterson, Filipski and Kumar2013).

Host–parasite network analysis

Host–parasite analysis was used to explore interactions by focusing on the level of host species (pooled host species at all study sites) (Paladsing et al., Reference Paladsing, Boonsri, Saesim, Changsap, Thaenkham, Kosoltanapiwat, Sonthayanon, Ribas, Morand and Chaisiri2020). A host–parasite matrix (presence/absence data, with host species in rows and helminth species in columns) was created using the ‘vegan’ (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Blanchet, Friendly, Kindt, Legendre, McGlinn, Minchin, O'Hara, Simpson, Solymos, Stevens, Szoecs and Wagner2020) and ‘bipartite’ packages (Dormann et al., Reference Dormann, Fruend, Gruber, Beckett, Devoto, Felix, Iriondo, Opsahl, Pinheiro, Strauss and Vázquez2021) in R freeware (R Core Team, 2021) v. 4.0.4. A bipartite network graph was generated with the ‘plotweb’ function showing infections in each host species. Network modularity was also computed using the ‘computeModules’ function and illustrated using the ‘plotModuleWeb’ function (Paladsing et al., Reference Paladsing, Boonsri, Saesim, Changsap, Thaenkham, Kosoltanapiwat, Sonthayanon, Ribas, Morand and Chaisiri2020). The mean number of interactions per species and the mean number of shared organisms were estimated using the function ‘grouplevel’.

Results

Helminth fauna of collected bats

A total of 163 bats of 21 species belonging to 6 families (Emballonuridae, Phyllostomidae, Mormoopidae, Noctilionidae, Molossidae and Vespertilionidae) were examined (Table 2). Parasitized bats were recorded in all the studied families except in Vespertilionidae.

Table 2. Bats sampled for this study in the Yucatan Peninsula

I, insectivore; S, sanguinivore; N, nectarivore; F, frugivore; P, piscivore.

Following morphological characterization and molecular analyses of the 28S gene, 20 helminth taxa were recorded: 7 trematodes Lecithodendriidae gen. sp., Nudacotyle quartus (Nudacotylidae), Limatulum sp. 1, Limatulum sp. 2 (Phaneropsolidae), Pygidiopsis macrostomum (Heterophydae), Urotrema minuta (Pleurogenidae) and Brachylecithum sp. (Dicrocoeliidae); 3 cestodes Vampirolepis sp. 1, Vampirolepis sp. 2 and Vampirolepis sp. 3 (Hymenolepididae) and 10 nematodes Spirurida fam. gen. sp., Strongylida fam. gen. sp., Capillaridae gen. sp., Pseudocapillaria sp. 1, Pseudocapillaria sp. 2, (Capillaridae), Anoplostrongylinae gen. sp., Linustrongylus pteronoti, Tricholeiperia cf. proencai, Anoplostrongylus sp. and Biacantha desmoda (Molineidae). Among these, 14 helminth taxa could not be morphologically identified at the genus or species level due to various reasons, such as the inadequate fixation of some specimens, the finding of only a single specimen, and the limited number of bat-associated helminth sequences in GenBank.

Infection levels

Forty-four (26.9%) bats of 12 species from 5 families were parasitized by helminths. Among these, 31 (70.4%) harboured 1 helminth species, 9 (20.4%) had 2 helminth species and 4 (9.1%) were infected by 3 parasite species.

The prevalence of each helminth species ranged from 7.1 (Anoplostrongylinae gen. sp.) to 100% (Spirurida fam. gen. sp., Limatulum sp. 1 and U. minuta) but in general, it did not exceed 50%. The mean intensity of infection ranged from 1 (e.g. Pseudocapillaria sp. 2, Lecithodendriidae gen. sp.) to 56 (e.g. Limatulum sp. 2), but in general it was higher for digeneans (Table 3).

Table 3. Infection levels of helminths of bats from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico

P, prevalence; MI, mean intensity, CI, 95% confidence interval values; SI, anatomical site of infection; L, liver; S, stomach; I, intestine.

Phylogenetic analysis

The results of the phylogenetic analyses confirmed that the 28S gene sequences derived from specimens identified morphologically as T. cf. proencai and P. macrostomum were identical to the published sequences for these parasites from Campeche (Panti-May et al., Reference Panti-May, Hernández-Mena, Torres-Castro, Estrella-Martínez, Lugo-Caballero, Vidal-Martínez and Hernández-Betancourt2021). On the other hand, the 28S sequences of the Vampirolepis sp. 1, Vampirolepis sp. 2, Vampirolepis sp. 3, Brachylecithum sp. and U. minuta specimens confirmed their identities at the genus or species level while for Anoplostrongylus sp., Pseudocapillaria sp. 1, N. quartus, Limatulum sp. 1 and Limatulum sp. 2, the obtained 28S sequences represent the first available genetic data.

The 28S sequences of T. cf. proencai and Anoplostrongylus and Pseudocapillaria sp. 1 were analysed separately in 2 data matrices due to genetic divergences between trichostrongylins and capillariids. The phylogenetic tree of Trichostrongylina grouped T. cf. proencai with another sequence of the same species from Campeche while Anoplostrongylus sp. was grouped as sister species of T. cf. proencai (bootstrap = 100) and they were nested in the same subclade with other species of the families Heligmonellidae and Trichostrongylidae, although with low support values (bootstrap = 33) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The genetic difference between T. cf. proencai and Anoplostrongylus sp. was 8%. For Capillaridae, the resulting phylogenetic tree showed that our sequence of Pseudocapillaria sp. 1 was nested in a subclade formed by Capillaria plica, Aonchotheca paranalis, Capillaria sp. and Baruscapillaria sp., with low support values (bootstrap = 40) (Supplementary Fig. S2). The genetic distances between Pseudocapillaria sp. 1 and the other capillariids were more than 40%.

The 28S sequences of Vampirolepis from Mexico were aligned with other 65 sequences belong to the family Hymenolepididae. The tree obtained was divided into 4 main clades, similar to those proposed by Haukisalmi et al. (Reference Haukisalmi, Hardman, Foronda, Feliu, Laakkonen, Niemimaa, Lehtonen and Henttonen2010) and Neov et al. (Reference Neov, Vasileva, Radoslavov, Hristov, Littlewood and Georgiev2019). Our specimens of Vampirolepis sp. 2 and Vampirolepis sp. 3 were grouped as sister species and nested with other specimens of Vampirolepis from bats in Finland and China with high support values (bootstrap = 95), while the specimen identified as Vampirolepis sp. 1 was nested with sequences of Pararodentolepis, Rodentolepis and Staphylocystis from rodents and eulipotyphlads (bootstrap = 100) (Fig. 2). The genetic distances between our 3 Vampirolepis sequences ranged from 2.2 to 4.6%.

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic tree based on the ML analysis constructed on partial large subunit ribosomal gene (28S) of hymenolepidids from different mammalian hosts (likelihood = −9474.057208). Grey bars mark hymenolepidid clades recognized by Haukisalmi et al. (Reference Haukisalmi, Hardman, Foronda, Feliu, Laakkonen, Niemimaa, Lehtonen and Henttonen2010) and Neov et al. (Reference Neov, Vasileva, Radoslavov, Hristov, Littlewood and Georgiev2019). The new sequences of the present study are in bold.

The alignment of Trematoda dataset comprised of 73 sequences, including sequences of P. macrostomum, N. quartus, U. minuta, Limatulum sp. 1, Limatulum sp. 2 and Brachylecithum sp. from the Yucatan Peninsula. Our specimens were grouped into 4 main clades (Fig. 3). The first clade grouped our sequence of P. macrostomum with other sequences of the same species (bootstrap = 100), and nested within the clade formed by other members of Heterophyidae with high support values (bootstrap = 100). The second clade included the families Nudacotylidae, Labicolidae, Opisthotrematidae and Notocotylidae (bootstrap = 100). The sequences of N. quartus were nested with other nudacotylids (bootstrap = 100) and had genetic distances that ranged from 2 to 4.9% with respect to the larva of Nudacotyle undicola from its intermediate host Biomphalaria pfeifferi in Kenya. The third clade grouped species from the families Lecithodendriidae, Stomylotrematidae, Prosthogonimidae, Pleurogenidae, Phaneropsolidae and Microphallidae (bootstrap = 100). In this clade, our specimens were grouped into 2 different subclades: the first included U. minuta and other species of Urotrema (bootstrap = 100) while the second subclade grouped Limatulum sp. 1 and Limatulum sp. 2 (bootstrap = 100). The genetic differences between our specimen of U. minuta and another sequence of the same species from Lasiurus seminolus in the USA, and between Limatulum sp. 1 and Limatulum sp. 2 were 0.3 and 4.4%, respectively. Finally, the 4th clade comprised members of the family Dicrocoeliidae. The sequence of Brachylecithum sp. was grouped as sister species of Brachylecithum grummti from Attila cinnamomeus in Brazil (bootstrap = 100); the genetic distance between these species was 2.1%.

Fig. 3. Phylogenetic tree based on the ML analysis constructed on partial large subunit ribosomal gene (28S) of Trematoda species from different hosts (likelihood = −13 934.207182). Some of the sequences included in the analysis were obtained from larvae of the intermediate hosts. The new sequences of the present study are in bold.

Host–parasite network analysis

The interactions between 12 species of bats (hosts) and 20 taxa of helminths (parasites) were explored through group indices, bipartite network and modularity graphs. The mean number of interactions per species was 1.2 for helminths and 2.4 for bats while the average number of shared organisms for helminths was 0.08 and 0.04 for bats.

Three helminth species were found in 2 bat species. Urotrema minuta was recorded in Eumops nanus and Nyctinomops laticaudatus, N. quartus in Artibeus jamaicensis and Chiroderma villosum, and Pseudocapillaria sp. 1 in Mormoops megalophylla and Pteronotus mesoamericanus. Six species of bats (Peropteryx macrotis, Glossophaga mutica, Desmodus rotundus, Pteronotus fulvus, Noctilio leporinus and Molossus nigricans) showed segregated species occurrence and were infected by different helminths than other bats such as A. jamaicensis, C. villosum, M. megalophylla, P. mesoamericanus, E. nanus and N. laticaudatus.

Nyctinomops laticaudatus was the only species parasitized by 4 helminth taxa, including cestodes, nematodes and trematodes. In contrast, in 6 bat species only 1 taxon was found (e.g. P. macrotis infected by Lecitodendridae gen. sp.) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Bipartite network graph illustrating the interactions of helminths of bats from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, based on presence–absence data (helminths: T = trematode, C = cestode, N = nematode; bats: I = insectivore, N = nectarivore, F = frugivore, S = sanguinivore, P = piscivore).

The bipartite network identified 11 modules (network modularity = 0.81) of parasite–host association. In each module, the helminths they contained were associated with 1 host species except in 1 module, which contained N. quartus in both A. jamaicensis and C. villosum (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Graph of the bipartite network that illustrates the modules that form in the parasite–host network of helminths of bats from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, based on presence–absence data.

Discussion

Helminth fauna of collected bats

This large-scale survey is the first to use an integrative taxonomy approach (morphological characters and phylogenetic analysis) to identify the helminth fauna of bats from Mexico. This allowed us to record 20 helminth taxa of bats from the Yucatan Peninsula. Before our work, 14 species had been reported in this region: 11 in Yucatan (Chitwood, Reference Chitwood1938; Stunkard, Reference Stunkard1938) and 3 in Campeche (Panti-May et al., Reference Panti-May, Hernández-Mena, Torres-Castro, Estrella-Martínez, Lugo-Caballero, Vidal-Martínez and Hernández-Betancourt2021). To the best of our knowledge, the order Spirurida, the genus Limatulum and U. minuta are reported for the first time in E. nanus in the Americas. This bat occurs from southeastern Gulf of Mexico to Guyana and Peru, but no previous records of helminths have been reported for it (Torres-Morales et al., Reference Torres-Morales, Rodríguez-Aguilar, Cabrera-Cruz and Villegas-Patraca2014; Santos and Gibson, Reference Santos and Gibson2015; Jiménez et al., Reference Jiménez, Caspeta-Mandujano, Ramírez-Chávez, Ramírez-Díaz, Juárez-Urbina, Peralta-Ramírez and Guerrero2017). In addition, N. quartus is reported for the first time from C. villosum (Santos and Gibson, Reference Santos and Gibson2015; Jiménez et al., Reference Jiménez, Caspeta-Mandujano, Ramírez-Chávez, Ramírez-Díaz, Juárez-Urbina, Peralta-Ramírez and Guerrero2017; Fugassa, Reference Fugassa2020), a bat species that occurs from southeastern Mexico to South America (Garbino et al., Reference Garbino, Lim and Tavares2020).

In addition, this study reports 6 new helminth–bat associations from Mexico: Anoplostrongylus sp., Brachylecithum sp. and U. minuta for N. laticaudatus, N. quartus for A. jamaicensis, Pseudocapillaria sp. 1 for M. megalophylla and P. mesoamericanus, and Pseudocapillaria sp. 2 for P. fulvus. The genus Anoplostrongylus has been previously recorded from N. laticaudatus in Cuba (Barus and del Valle, Reference Barus and del Valle1967) and Tadarida brasiliensis and Eumops perotis in Brazil (Santos and Gibson, Reference Santos and Gibson2015). Mostly species of Brachylecithum are parasites of birds, although some infect small mammals (Rodentia, Insectivora and Chiroptera). For example, in bats, Brachylecithum taiwanense has been reported in Hipposideros armiger from Taiwan (Casanova and Ribas, Reference Casanova and Ribas2004; Hildebrand et al., Reference Hildebrand, Sitko, Zaleśny, Jeżewski and Laskowski2016). Species of Urotrema have been described in various mammal and lizard species. In bats, this genus mainly parasitizes insectivorous species from American and African continents (Martínez-Salazar et al., Reference Martínez-Salazar, Medina-Rodríguez, Rosas-Valdez, del Real-Monroy and Falcón-Ordaz2020). To date, Urotrema scabridum is the only species recorded in several species of bats from Mexico (Caspeta-Mandujano et al., Reference Caspeta-Mandujano, Peralta-Rodríguez, Ramírez-Díaz and Tapia-Osorio2017). The genus Pseudocapillaria occurs in the Americas, Europe, Asia and Oceania and includes species that parasitize fishes, reptiles, birds and mammals (Moravec, Reference Moravec1982, Reference Moravec2002). In American bats, Pseudocapillaria pillosa has been reported from Sturnira lilium and Lonchophylla robusta in Brazil and Colombia (Santos and Gibson, Reference Santos and Gibson2015).

Infection levels

The overall helminth infection in bats from the Yucatan Peninsula was 26.9%. When we compared this result with other surveys of multiple species of bats, we observed that most studies reported higher infection values, for example in the USA (37.3–63%) (Pistole, Reference Pistole1988; Hilton and Best, Reference Hilton and Best2000), Mexico (40%) (Salinas-Ramos et al., Reference Salinas-Ramos, Herrera, Hernández-Mena, Osorio-Sarabia and León-Règagnon2017), Peru (56.7%) (Minaya et al., Reference Minaya, Saez, Chero de la Cruz, Cruces and Iannacone2020), Argentina (61.3%) (Milano, Reference Milano2016) and Egypt (43.9%) (Saoud and Ramadan, Reference Saoud and Ramadan1976). On the other hand, similar infection levels (20.9–26%) have been reported in bats from Brazil (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, de Fabio and Peracchi2004; de Albuquerque et al., Reference de Albuquerque, Duarte, Silva, Lapera, Tebaldi and Lux2016). This variation in helminth infection may be associated with different factors, such as the sample size (Poulin and Morand, Reference Poulin and Morand2000), the tropic group of studied bats (Hilton and Best, Reference Hilton and Best2000), the sampling period, season (Salinas-Ramos et al., Reference Salinas-Ramos, Herrera, Hernández-Mena, Osorio-Sarabia and León-Règagnon2017) and the environment surrounding roost sites (Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Kohler and Vonhof2016).

Although nematodes were the most diverse group of helminths, trematodes had the highest prevalence and mean intensity values. This has been observed in similar studies in Brazil (de Albuquerque et al., Reference de Albuquerque, Duarte, Silva, Lapera, Tebaldi and Lux2016), the USA (Hilton and Best, Reference Hilton and Best2000), England (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Parker, Parker and Brooks2012), Spain (Esteban et al., Reference Esteban, Amengual and Cobo2001) and Egypt (Saoud and Ramadan, Reference Saoud and Ramadan1976). It is important to point out the occurrence of trematodes in frugivorous bats such as A. jamaicensis and C. villosum. Although the feeding ecology of most Neotropical bat species is still poorly known (Nogueira and Peracchi, Reference Nogueira and Peracchi2003), the presence of insects in the diet of A. jamaicensis has been reported (Ortega and Castro-Arellano, Reference Ortega and Castro-Arellano2001), which could explain the trematode infection by ingestion of infected intermediate hosts. Transmission of trematodes through consumption of water or vegetation contaminated with infective stages is also plausible. Ameel (Reference Ameel1944) reported that metacercariae of Nudacotyle novicia were immediately infective after encystment on the surface of vegetation and water.

Phylogenetic analysis

In our study, the phylogenetic position of nematodes was ambiguous with low clade support values due to the limited number of the 28S gene sequences available in GenBank. The generation of subsequent 28S sequences may help to improve the resolution of the phylogenetic relationships of nematodes at supraspecific levels (e.g. genera and families).

The general configuration of our phylogenetic tree of hymenolepidids (Fig. 2) was similar to the previous phylogenetic hypothesis for relationships among members of the family Hymenolepididae from mammals (Haukisalmi et al., Reference Haukisalmi, Hardman, Foronda, Feliu, Laakkonen, Niemimaa, Lehtonen and Henttonen2010; Neov et al., Reference Neov, Vasileva, Radoslavov, Hristov, Littlewood and Georgiev2019). We added 3 sequences of Vampirolepis from Neotropical bats belonged to the families Phyllostomidae, Mormoopidae and Molossidae. This genus is poorly represented in GenBank; only 2 sequences are available, 1 from Finland and the other 1 from China. Our analysis revealed the same main phylogenetic clades proposed by Haukisalmi et al. (Reference Haukisalmi, Hardman, Foronda, Feliu, Laakkonen, Niemimaa, Lehtonen and Henttonen2010) and confirmed by Neov et al. (Reference Neov, Vasileva, Radoslavov, Hristov, Littlewood and Georgiev2019): Arostrilepis clade, Ditestolepis clade, Hymenolepis clade and Rodentolepis clade. The latter contained cestodes of rodents, shrews and bats and diverged in several groups. One of them included our sequences of Vampirolepis sp. 2 and Vampirolepis sp. 3 and other 2 sequences of Vampirolepis. In contrast, Vampirolepis sp. 1 was grouped with the genera Staphylocystis and Pararodentolepis from shrews and rodents. This suggests the non-monophyletic position of the genus Vampirolepis due to the distant position of Vampirolepis sp. 1 and its relationship with the subclade harbouring the genera Staphylocystis and Pararodentolepis. The parasite–host patterns across the phylogenetic tree of mammalian hymenolepidids suggest the presence of events of host switching during the process of parasite diversification, including host switching between members of different mammalian orders (Neov et al., Reference Neov, Vasileva, Radoslavov, Hristov, Littlewood and Georgiev2019).

The 28S gene has been extensively sequenced in trematodes (Pérez-Ponce de León and Hernández-Mena, Reference Pérez-Ponce de León and Hernández-Mena2019), which allow us to corroborate our morphological identifications at different taxonomic levels. Although the identification of P. macrostomum and U. minuta was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis, for other species such as Brachylecithum sp. and N. quartus the corroboration was only up to the genus level. In the case of Brachylecithum sp., the ambiguity of some morphological characters (e.g. the length of caeca) made its morphological determination difficult at the genus level; however, the result of the phylogenetic analysis allowed us to position it as a sister species of B. grummti. Despite the vast 28S sequences of digeneans available in GenBank, no previous sequences of Limatulum had been sequenced. The phylogenetic analysis confirms our morphological hypothesis that 2 Limatulum species were found in the Yucatan Peninsula.

The increased availability of gene sequences of parasites in the last 2 decades has contributed to the accelerated description of parasite biodiversity. The addition of molecular analyses to traditional morphological descriptions has become part of the accepted best practice to characterize helminth species (Poulin and Presswell, Reference Poulin and Presswell2016; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Hay and Jorge2019). In this sense, genetic data can be an information source for the diagnosis and taxonomy of helminths, especially for those groups that present complications in their systematics (e.g. Dicrocoelidae) (Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Hay and Jorge2019; Suleman et al., Reference Suleman Khan, Tkach, Muhammad, Zhang and Zhu2020) or when key taxonomic characters cannot be studied due to insufficient or incomplete material (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Niu, Chen, Liu, Li, Jiang, Wang, Cui and Zhang2021). Our results highlight the importance of complementing morphological identification of helminths of Neotropical bats with molecular tools.

Host–parasite network analysis

In this study, almost all helminths were associated with a specific bat. This result has also been observed by Hilton and Best (Reference Hilton and Best2000) in bats from Alabama, USA. The helminth specificity may be associated with the diet of bats, which may predispose a host to be infected with specific helminths and their infective stages (Hilton and Best, Reference Hilton and Best2000; Salinas-Ramos et al., Reference Salinas-Ramos, Herrera, Hernández-Mena, Osorio-Sarabia and León-Règagnon2017). For instance, guppies (Poeciliidae) are the second intermediate hosts of P. macrostomum, a parasite reported from the piscivorous bat N. leporinus. The high number of modules indicates marked differences in the helminth fauna even between species of the same trophic guild, which may be associated with factors such as the types of prey (potential intermediate hosts) and the sites of foraging that may vary between species (Hilton and Best, Reference Hilton and Best2000; Clarke-Crespo et al., Reference Clarke-Crespo, Pérez-Ponce de León, Montiel-Ortega and Rubio-Godoy2017). In addition, this may be related to phylogenetic relationship because more related host species (e.g. from the same family or genus) tend to harbour more similar helminth fauna (Poulin, Reference Poulin2014).

We identified that 3 helminth species occurred in 2 host species, N. quartus in A. jamaicensis and C. villosum, Pseudocapillaria sp. 1 in M. megalophylla and P. mesoamericanus and U. minuta in E. nanus and N. laticaudatus. This ability of parasites to infect multiple hosts has been linked to coevolutionary relationships, environment, geography and trait matching between host and parasite (Dallas et al., Reference Dallas, Park and Drake2017). Coevolutionary relationships often lead to host specificity, the degree to which parasites are restricted to particular species of hosts (Poulin, Reference Poulin2010). Closely related hosts may harbour the same parasite because they have similar physiology or immunology or because they provide similar habitats and resources (Presley et al., Reference Presley, Dallas, Klingbeil and Willig2015). In our context, the helminth species that were found in more than 1 host, parasitized bats of the same family (i.e. N. quartus in phyllostomids, Pseudocapillaria sp. 1 in mormoopids and U. minuta in molossids). It has also been noted that parasites with heteroxenous life cycles that include 1 or 2 intermediate hosts have more opportunities to switch hosts (Presley et al., Reference Presley, Dallas, Klingbeil and Willig2015). This may arise because free-living infective larvae and infected intermediate hosts containing larval stages may survive for long periods and be exposed to various definitive hosts. Although most investigations of bat-associated helminths have illustrated a dominance of digeneans, most life cycles of this group of parasites remain completely unknown (Blasco-Costa and Poulin, Reference Blasco-Costa and Poulin2017), such as of the Pleurogenidae (Tkach et al., Reference Tkach, Greiman, Pulis, Brooks and Bonilla2019).

Insectivorous bats harboured more helminth species in the Yucatan Peninsula. Species such as N. laticaudatus, P. fulvus, M. megalophylla and E. nanus harboured more helminth taxa compared to bats with other types of feeding such as nectarivores (e.g. Glossophaga mutica) and sanguinivores (e.g. D. rotundus). Similar results have been reported from bats in Brazil and Argentina (de Albuquerque et al., Reference de Albuquerque, Duarte, Silva, Lapera, Tebaldi and Lux2016; Milano, Reference Milano2016), which may be associated with the consumption of potential intermediate hosts for cestodes and trematodes (Clarke-Crespo et al., Reference Clarke-Crespo, Pérez-Ponce de León, Montiel-Ortega and Rubio-Godoy2017; Salinas-Ramos et al., Reference Salinas-Ramos, Herrera, Hernández-Mena, Osorio-Sarabia and León-Règagnon2017). On the other hand, the presence of heteroxenous species in frugivorous (A. jamaicensis and C. villosum) and nectarivorous (G. mutica) bats suggests they may consume insects as a part of their diets or acquire the infection through the incidental ingestion of intermediate hosts.

Our study was limited by the sample size of bats, the sampling period and the use of 1 gene. Nevertheless, our study is the first large-scale survey of helminths of bats that use an integrative taxonomy approach in Mexico. We provided new host records and nucleotide sequences of some helminths (e.g. N. quartus and Limatulum sp. 1) that help us to increase the information available on parasites of bats for future studies. Furthermore, this is the first study that explores the parasite–host interactions in bats in Mexico, which is required to know and understand the transmission patterns of helminths and the relative influence of environmental factors on spatial variation of community composition.

Conclusion

A high richness (20 taxa) of helminths was found in bats from the Yucatan Peninsula. The prevalence and intensity of infection varied widely. We noted that most helminths parasitize a single host species, and that the insectivorous species had the highest richness of helminths. It would be advisable to conduct further studies examining seasonal and geographical factors as well as intrinsic factors affecting helminth infections. This can help us to increase our knowledge on the helminths parasitizing bats in Mexico and other Neotropical areas.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182022001627.

Data

All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information file.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Alejandro Oceguera and the students of the Colección Nacional de Helmintos for their support during the laboratory work at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. We would also like to thank Erendira Estrella Martínez for her support at the Colección Zoológica, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.

Author's contributions

J. A. P.-M. and W. I. M.-C. conceived and designed the study. M. T.-C., S. F. H.-B., M. C. M. G., C. I. S.-S., W. I. M.-C. and J. A. P.-M. conducted fieldwork. J. A. P.-M., W. I. M.-C., D. I. H.-M. and L. G.-P. conducted morphological analyses. D. I. H.-M., W. I. M.-C. and V. M. V.-M. performed molecular analyses. W. I. M.-C. and R. C. B.-M. performed statistical analyses. J. A. P.-M. and W. I. M.-C. wrote the article with input from D. I. H.-M., M. T.-C., R. C. B.-M., S. F. H.-B., M. C. M. G., L. G.-P., V. M. V.-M. and C. I. S.-S.

Financial support

This work was funded by the CONACYT-México, projects ‘Análisis y evaluación de los posibles vectores y reservorios del virus del Ébola en México’, grant no. 251053; ‘Plataformas de observación oceanográfica, línea base, modelos de simulación y escenarios de la capacidad natural de respuesta ante derrames de gran escala en el Golfo de México’, grant no. 201441 and the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México ‘Programa de apoyo a proyectos de investigación e innovación tecnológica’, grant no. IN215722. The first author was supported by a grant for master's degree from CONACYT (grant no. 001398).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The bioethics committee of the Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (protocol numbers CB-CCBA-I-2018-001, CB-CCBA-I-2020-002) approved all protocols used in this study.