Introduction

Infections by unicellular protozoan parasites are a major worldwide health concern. It is estimated that parasitic diseases cause more than 1 million deaths every year and billions endure the morbidity of infection. Infections caused by intracellular parasites of the phylum Apicomplexa are the most prevalent, severely compromise human health, and impact animal food production. The most medically important Apicomplexa are the Plasmodium species, the causative agents of malaria, and in particular Plasmodium falciparum, which is responsible for most malaria-related deaths (WHO, 2018). Increased prevention and control measures have led to a marked reduction in malaria mortality rate, but this disease still claims half a million lives every year. Because of their lower mortality burden, other parasitic diseases rarely make headlines. However, toxoplasmosis and cryptosporidiosis also pose important health problems. In immunocompetent hosts, toxoplasmosis is characterized by mild-flu symptoms, whereas newborns and immunocompromised patients may suffer from severe ocular infections or encephalitis. Primary infection with Toxoplasma gondii is also associated with fetal malformations or death of the foetus. Additionally, Cryptosporidium parvum has been recently identified as one of the leading causes of diarrhoeal disease in children below 2 years of age in developing countries (Kotloff et al., Reference Kotloff, Nataro, Blackwelder, Nasrin, Farag, Panchalingam, Wu, Sow, Sur, Breiman, Faruque, Zaidi, Saha, Alonso, Tamboura, Sanogo, Onwuchekwa, Manna, Ramamurthy, Kanungo, Ochieng, Omore, Oundo, Hossain, Das, Ahmed, Qureshi, Quadri, Adegbola, Antonio, Hossain, Akinsola, Mandomando, Nhampossa, Acacio, Biswas, O'Reilly, Mintz, Berkeley, Muhsen, Sommerfelt, Robins-Browne and Levine2013). Toxoplasma, Cryptosporidium and several other Apicomplexa (e.g. Theileria, Babesia, and Eimeria) also affect livestock and are associated with important economic losses. A lack of effective anti-parasitic vaccines combined with an increase in drug resistance, rapid geographical expansion of vectors, extensive human migration and global transportation of merchandise make parasitic diseases among the most important public health challenges (Nyame et al., Reference Nyame, Kawar and Cummings2004). New therapies are needed and a comprehensive understanding of the molecular basis of host–pathogens interactions, together with basic parasite biology, will be crucial for the design of highly specific and efficient anti-parasitic drugs.

Glycans and glycan-binding proteins are known to play a role of paramount importance in host–pathogen interactions. Adhesion of parasites or other microbes to host cells involves interactions between glycan-binding proteins, also called lectins or adhesins, and glycan receptors. These interactions are a prerequisite for infection and often define the tropism of the pathogen. Furthermore, parasite glycans are often antigenic and may trigger both the innate and adaptive immune responses of the host. In addition, glycosylation of intracellular proteins can play roles in signalling and affect parasite proliferation and virulence. Studying the major roles of glycans in promoting parasitic infections and evading host immune responses may lead to the development of novel therapeutic agents, the identification of vaccine candidates and the development of novel diagnostic tools (Guha-Niyogi et al., Reference Guha-Niyogi, Sullivan and Turco2001; Mendonca-Previato et al., Reference Mendonca-Previato, Todeschini, Heise and Previato2005; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Acosta-Serrano, Aebi, Ferguson, Routier, Schiller, Soares, Spencer, Titz, Wilson and Izquierdo2015; Goddard-Borger and Boddey, Reference Goddard-Borger and Boddey2018).

Until the mid-1990s only scarce and often controversial information existed regarding glycosylation in apicomplexan parasites (Schwarz and Tomavo, Reference Schwarz and Tomavo1993). In this pre-genomic era, glycosylphosphatidylinositols (GPIs) were shown to be synthesized by T. gondii and P. falciparum. As in other protozoan parasites, these glycans are abundantly present as proteins anchors or as free glycolipids and are essential for parasite survival (reviewed in Debierre-Grockiego and Schwarz, Reference Debierre-Grockiego and Schwarz2010). The availability of whole genome sequences enabled predicting biosynthetic pathways of glycans in various apicomplexa and revealed divergence between species of this phylum (Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Schwarz, Todeschini, Previato and Mendonca-Previato2010; Cova et al., Reference Cova, Rodrigues, Smith and Izquierdo2015; Samuelson and Robbins, Reference Samuelson and Robbins2015). The presence of a few Alg (Asparagine-linked glycosylation) genes in Plasmodium falciparum genome challenged the belief that Plasmodium does not express any N-glycosylated proteins. Indeed this parasite was shown to synthesize rudimentary N-glycans containing 1 or 2 N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues, in agreement with the set of genes present in this organism (Bushkin et al., Reference Bushkin, Ratner, Cui, Banerjee, Duraisingh, Jennings, Dvorin, Gubbels, Robertson, Steffen, O'Keefe, Robbins and Samuelson2010). In contrast, Toxoplasma and other coccidian parasites maintained a larger N-glycan machinery and are able to synthesize a N-glycan precursor with 2 GlcNAc, 5 mannose (Man) and up to 3 glucose (Glc) residues (reviewed in Samuelson and Robbins, Reference Samuelson and Robbins2015).

In this review, we focus on other types of glycosylation recently described. Plasmodium falciparum is thought to be devoid of mucin-type O-glycans since the necessary genes and donor substrate UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine (UDP-GalNAc) are lacking in this parasite (Templeton et al., Reference Templeton, Iyer, Anantharaman, Enomoto, Abrahante, Subramanian, Hoffman, Abrahamsen and Aravind2004; Cova et al., Reference Cova, Rodrigues, Smith and Izquierdo2015; Lopez-Guttierez et al., Reference Lopez-Gutierrez, Dinglasan and Izquierdo2017). Similarly, no homologue of the O-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (OGT), responsible for dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, is present in the genome of the malaria parasite (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Robbins and Samuelson2009). In striking contrast, Toxoplasma adds O-linked GalNAc to mucin-like proteins, modifies nuclear proteins using an O-fucosyltransferase (OFT) similar to OGT, and glycosylates the cytosolic protein Skp1.

In the second part of this review, we address O-fucosylation and C-mannosylation of thrombospondin type 1 repeats (TSRs), newly described in key adhesins of both Plasmodium and Toxoplasma.

Mucin-type O-Glycans

Transfer of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) to the hydroxyl group of specific serine (Ser) or threonine (Thr) residues initiates O-GalNAc glycosylation, a common post-translational modification of secreted or membrane-associated proteins in eukaryotes. This type of glycosylation is also referred to as mucin-type O-glycosylation, since mucins carry hundreds of heterogeneous O-GalNAc glycans in specific domains composed of Ser-, Thr-, and proline (Pro)-rich tandem repeats. This high O-GalNAc glycans density controls the chemical, physical and biological properties of mucins (Brockhausen and Stanley, Reference Brockhausen, Stanley, Varki, Cummings, Esko, Stanley, Hart, Aebi, Darvill, Kinoshita, Packer, Prestegard, Schnaar and Seeberger2017).

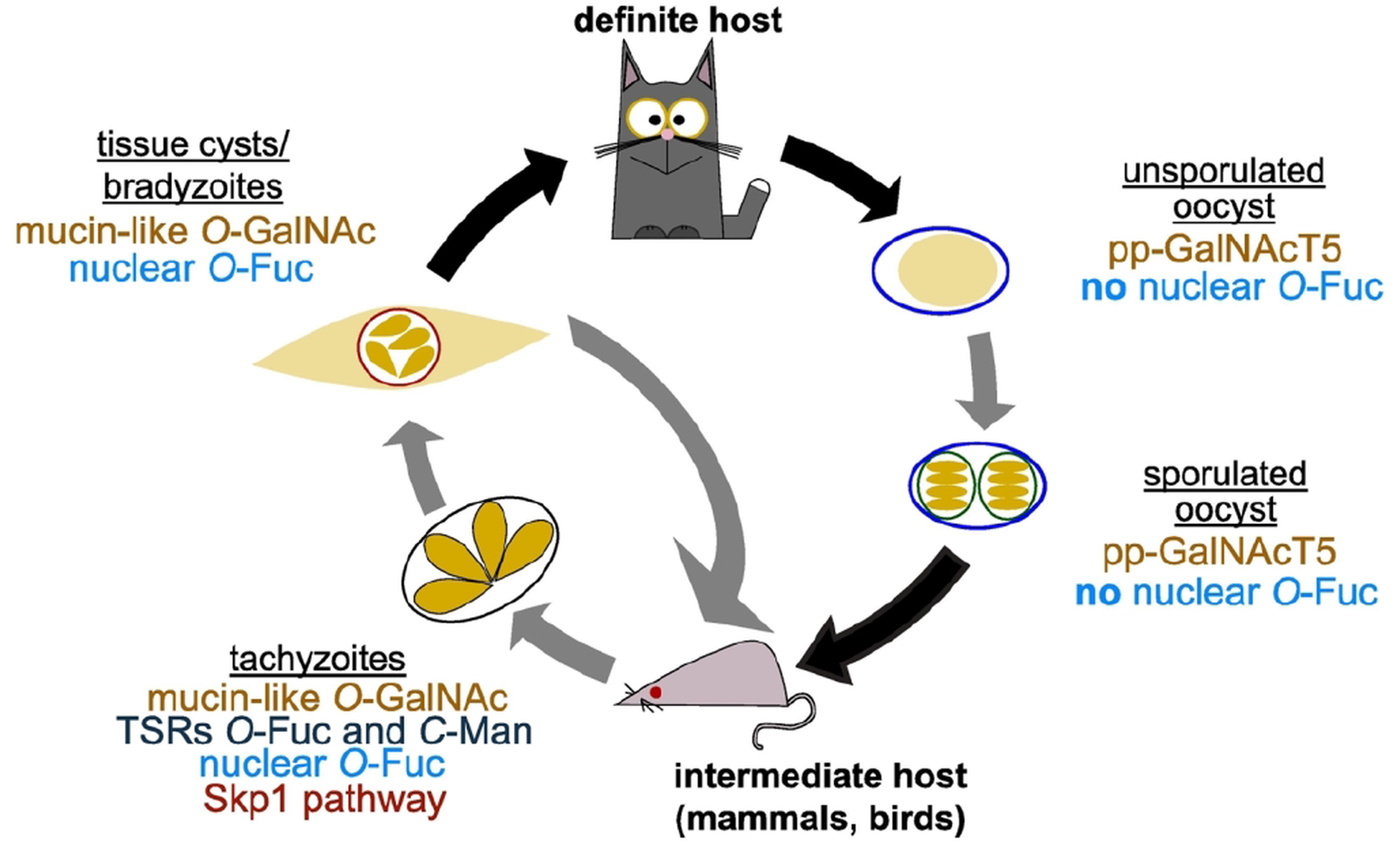

Mucin-type O-glycosylation is initiated by a family of UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases (pp-GalNAcTs) evolutionary conserved from unicellular eukaryotes to mammals. They catalyse the transfer of GalNAc from the donor UDP-GalNAc to the hydroxyl group of Ser or Thr residues in acceptor proteins to form GalNAcα1-O-Ser/Thr. This structure known as the Tn antigen is usually elongated further to give rise to a variety of complex O-GalNAc glycans in mammalian cells (Brockhausen and Stanley, Reference Brockhausen, Stanley, Varki, Cummings, Esko, Stanley, Hart, Aebi, Darvill, Kinoshita, Packer, Prestegard, Schnaar and Seeberger2017). The genome of T. gondii encodes five putative pp-GalNAcTs (pp-GalNAcT1: TGGT1_259530; pp-GalNAcT2: TGGT1_258770; pp-GalNAcT3: TGGT1_318730; pp-GalNAcT4: TGGT1_256080; pp-GalNAcT5: TGGT1_278518) (Wojczyk et al., Reference Wojczyk, Stwora-Wojczyk, Hagen, Striepen, Hang, Bertozzi, Roos and Spitalnik2003; Stwora-Wojczyk et al., Reference Stwora-Wojczyk, Dzierszinski, Roos, Spitalnik and Wojczyk2004a, Reference Stwora-Wojczyk, Kissinger, Spitalnik and Wojczyk2004b; Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017; Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019). Toxoplasma gondii pp-GalNAcT1, T2 and T3 are constitutively expressed in both tachyzoites and bradyzoites, whereas pp-GalNAcT4 and T5 are expressed in the cat enteroepithelial stages, and T5 is additionally found in oocysts (Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017). These enzymes have a type II topology with a short N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, a single transmembrane domain, a stem region and a conserved catalytic domain (Fig. 1A). With the exception of pp-GalNAcT4, they also have a C-terminal, ricin-like lectin domain. The catalytic domain adopts a glycosyltransferase A-fold with a DxH motif involved in divalent ion binding (Stwora-Wojczyk et al., Reference Stwora-Wojczyk, Kissinger, Spitalnik and Wojczyk2004b; Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017). As in mammals, the enzymes seem to act in a hierarchical manner. The enzyme pp-GalNAcT2 is the priming glycosyltransferase required for initial glycosylation of the mucin-like domain (Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017). O-glycosylation of neighbouring acceptor sites is then carried out by the follow-on pp-GalNAcTs, pp-GalNAcT1 and T3, leading to a densely glycosylated mucin-like domain (Fig. 1A). In vitro, both pp-GalNAcT1 and T3 are only able to use pre-glycosylated acceptor peptides but not unglycosylated ones (Wojczyk et al., Reference Wojczyk, Stwora-Wojczyk, Hagen, Striepen, Hang, Bertozzi, Roos and Spitalnik2003; Stwora-Wojczyk et al., Reference Stwora-Wojczyk, Kissinger, Spitalnik and Wojczyk2004b). Active pp-GalNAcTs have also been described in Cryptosporidium (Bhat et al., Reference Bhat, Wojczyk, DeCicco, Castrodad, Spitalnik and Ward2013; Haserick et al., Reference Haserick, Klein, Costello and Samuelson2017; DeCicco RePass et al., Reference DeCicco RePass, Bhat, Heimburg-Molinaro, Bunnell, Cummings and Ward2018), while the genome of Plasmodium lacks genes encoding these enzymes.

Fig. 1. Mucin-type O-glycosylation in T. gondii. (A) Model for mucin-type glycosylation in tachyzoites and bradyzoites. Mucin domains are modified with GalNAc in a hierarchical manner by the activity of pp-GalNAcT2, followed by pp-GalNAcT1 and T3. The activity of these enzymes is dependent of the import of UDP-GalNAc in the Golgi by TgNST1. The resulting structures are recognized by Vicia villosa lectin (VVL) and the anti-Tn antibody. A still unknown glycosyltransferase is believed to transfer a second GalNAc residue, leading to the GalNAcα1,3GalNAc epitope recognized by Dolichos Biflorus agglutinin (DBA). (B) Candidate O-glycosylated proteins have been identified by lectin enrichment in tachyzoites. They localize to secretory organelles found at the apical end of the parasite (as shown by the electron micrograph and the schematic), the inner membrane complex, or the parasitophorous vacuole. Rhoptries, r; conoid, c; inner membrane complex, dark arrow. Subpellicular microtubules are shown in gray in the schematic but are not visible in the micrograph. (C) Bradyzoites are surrounded by a glycan-rich cyst wall containing the proteins CST1 and SRS13. Both proteins contain a mucin domain with Thr-rich repeats extensively modified by O-linked GalNAc glycans. Glycosylation of CST1 confers rigidity to the cyst wall.

As early as the late 1970s, it was observed that Dolichos Biflorus agglutinin (DBA), a lectin with specificity for GalNAcα1,3GalNAc, effectively stained the glycosylated wall of Toxoplasma cysts that contain bradyzoites (slow-growing forms) (Sethi et al., Reference Sethi, Rahman, Pelster and Brandis1977). DBA and other lectins that recognize non-reducing terminal GalNAc residues, such as Vicia villosa lectin (VVL), were used for affinity purification of T. gondii glycoproteins. Coupled with mass spectrometry (MS), this lectin-capture approach identified candidate glycoproteins, including components of the tissue cyst wall, secreted proteins from the secretory organelles (rhoptries, micronemes and dense granules), and proteins from the parasitophorous vacuole and the inner membrane complex (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Upadhya, Zhang, Madrid-Aliste, Nieves, Kim, Angeletti and Weiss2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Peng, Huang, Xia, Vermont, Lentini, Lebrun, Wastling and Bradley2016) (Fig. 1B). Additionally, transfer of GalNAc to the hydroxyl of Ser/Thr in mucin-like domains by pp-GalNAcTs generates GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr, which is immunogenic in the host. Antibodies directed against this Tn antigen recognized at least 6 proteins ranging from 20 to 60 kDa (Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019). DBA staining of the cyst wall is principally due to O-glycosylation of the mucin-like glycoprotein CST1, since deletion of CST1, pp-GalNAcT2, or pp-GalNAcT3 led to a loss of staining by this lectin (Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Bzik, Ma, Fox, Markillie, Taylor, Kim and Weiss2013, Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017). CST1 confers structural rigidity to the cyst wall, and the O-GalNAc modification is required for this function (Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017). Like CST1, SRS13 (surface antigen-1 related sequence 13) contains a Thr-rich mucin-like domain that is heavily O-glycosylated by pp-GalNAcT2 and T3 (Fig. 1C). This protein is upregulated in bradyzoites but is dispensable for cell wall formation (Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Ma and Weiss2018). In contrast T. gondii proteophosphoglycan 1 (TgPPG1), a Ser/Pro rich-protein that shows similarities to the proteophosphoglycans of Leishmania parasites, enhances cell wall formation. Based on its retention in the stacking gel of SDS-PAGE, TgPPG1 is likely highly glycosylated (Craver et al., Reference Craver, Rooney and Knoll2010; Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Bzik, Ma, Fox, Markillie, Taylor, Kim and Weiss2013). The prominent role of O-GalNAc glycosylation in the encysted form of Toxoplasma is highlighted by deletion of the genes encoding pp-GalNAcT2 and T3 or the nucleotide sugar transporter 1 (TgNST1, TGGT1_267380), which imports UDP-GalNAc and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) into the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi apparatus for biosynthesis of glycans. Deficiency of pp-GalNAcT2 or T3 leads to fragile brain cysts, likely due to the absence of CST1 glycosylation, while a lower cyst load in the brain was observed in TgNST1-deficient parasites. In contrast, deletion of these genes did not significantly impact the tachyzoite stage of the parasite (Caffaro et al., Reference Caffaro, Koshy, Liu, Zeiner, Hirschberg and Boothroyd2013; Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017).

Recently, a study of total O-glycans released by β-elimination from Toxoplasma tachyzoites suggested that this parasite stage expresses only one major mucin-type O-glycan containing two N-acetylhexosamines (Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019). The epimerase generating UDP-GalNAc from UDP-GlcNAc (GalE) is necessary for the formation of this O-linked disaccharide. This result indicates the presence of at least one GalNAc residue at the reducing end, which is consistent with the expression of pp-GalNAcTs in this parasite stage. Based on previous studies with lectins (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Peng, Huang, Xia, Vermont, Lentini, Lebrun, Wastling and Bradley2016; Tomita et al., Reference Tomita, Sugi, Yakubu, Tu, Ma and Weiss2017), the authors suggest the structure GalNAc-GalNAc and possibly GalNAcα1,3GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr, which is preferentially recognized by DBA (Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019). The glycosyltransferase that extends the O-linked GalNAc has not yet been identified (Fig. 1A).

Nucleocytosolic glycosylation in T. gondii

Studies performed in the last 30 years have underlined the fact that glycosylation of proteins in the nucleus and cytosol is not an exception, but a conserved feature in most eukaryotes. O-GlcNAcylation, the modification of nucleocytoplasmic proteins with a single GlcNAc residue, was first described in mammals in the early 80s. It was followed a decade later by the initial identification of the Skp1 glycosylation pathway in Dictyostelium discoideum (West and Hart, Reference West, Hart, Varki, Cummings, Esko, Stanley, Hart, Aebi, Darvill, Kinoshita, Packer, Prestegard, Schnaar and Seeberger2017) and, in the last 2 years, the identification of O-mannose in yeast (Halim et al., Reference Halim, Larsen, Neubert, Joshi, Petersen, Vakhrushev, Strahl and Clausen2015) and O-fucose in T. gondii and Arabidopsis thaliana (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Haserick, Motari, Ouologuem, Lourido, Roos, Costello, Robbins and Samuelson2016; Zentella et al., Reference Zentella, Sui, Barnhill, Hsieh, Hu, Shabanowitz, Boyce, Olszewski, Zhou, Hunt and Sun2017).

The Skp1 glycosylation pathway

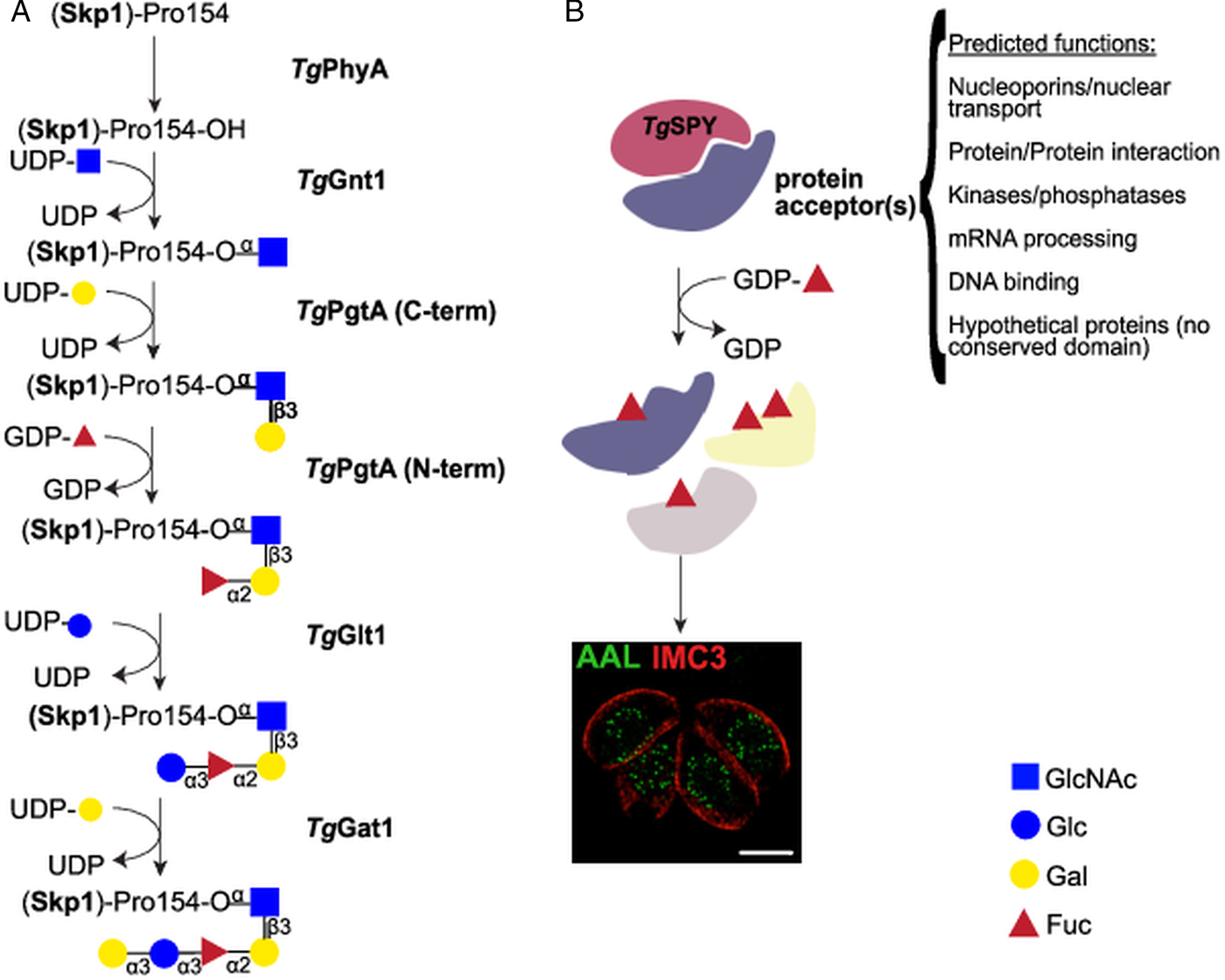

In T. gondii, the proline 154 of Skp1 (S-phase kinase-associated protein 1), an adaptor of Skp1/Cullin1/F-box protein (SCF)-class E3 ubiquitin ligases, is hydroxylated and further modified by a pentasaccharide (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Zhao, Mandalasi, van der Wel, Wells, Blader and West2016, Reference Rahman, Mandalasi, Zhao, Sheikh, Taujale, Kim, van der Wel, Matta, Kannan, Glushka, Wells and West2017; West and Hart, Reference West, Hart, Varki, Cummings, Esko, Stanley, Hart, Aebi, Darvill, Kinoshita, Packer, Prestegard, Schnaar and Seeberger2017; Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019) (Fig. 2A). This glycosylation pathway is involved in the response of Dictyostelium to changes in environmental oxygen (West et al., Reference West, Wang and van der Wel2010). Detection and monitoring of oxygen levels is a function required by all cells and, in eukaryotes, cytosolic proline 4-hydroxylases (P4Hs) act as key oxygen sensors (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Brown, Wang, van der Wel, Teygong, Zhang, Blader and West2012a). While the hydroxylation mechanism is conserved between animals and protists, the protein targets differ. In animals, P4Hs modify the transcriptional co-factor, hypoxia-inducible factor-α (HIFα). At normal oxygen levels, hydroxylation of HIFα leads to its poly-ubiquitination and subsequent proteosomal degradation, blocking the transcription of hypoxia-specific genes (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Wang, Green and West2012b). In protists such as Toxoplasma and Dictyostelium a single proline on Skp1 is hydroxylated and then further modified by a pentasaccharide. This modification does not lead to Skp1 degradation, but instead likely influences poly-ubiquitination and targeting to the proteasome of many other proteins (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Brown, Wang, van der Wel, Teygong, Zhang, Blader and West2012a). In T. gondii, gene disruption of either the proline hydroxylase (phyA) or the four glycosyltransferases required for the pentasaccharide synthesis, although tolerated, leads to defects in parasite replication in the host. As might be expected, the strongest phenotype is observed in mutants lacking glycosylation, while milder growth defects are observed in mutants with reduced glycosylation (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Brown, Wang, van der Wel, Teygong, Zhang, Blader and West2012a; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Zhao, Mandalasi, van der Wel, Wells, Blader and West2016, Reference Rahman, Mandalasi, Zhao, Sheikh, Taujale, Kim, van der Wel, Matta, Kannan, Glushka, Wells and West2017).

Fig. 2. Nucleocytosolic glycosylation pathways in T. gondii. (A) Skp1 glycosylation pathway. Proline 154 of the Skp1 protein is first hydroxylated by TgPhyA and then modified by a pentasaccharide of the composition Galα1,3Glcα1,3Fucα1,2Galβ1,3GlcNAcα1– which is assembled by four glycosyltransferases. Transfer of αGlcNAc to the hydroxylated proline by TgGnt1 is followed by the sequential transfer of β1,3-linked Gal and α1,2Fuc by the bifunctional enzyme TgPgtA. TgGlt1 and TgGat1 transfer the remaining two sugars, Glc and Gal, both in α1,3 linkage. (B) Nucleocytosolic O-fucosylation. TgSPY, a paralogue of animal O-GlcNAc transferases, modifies more than 60 proteins with one or more O-linked fucose residues. Structured illumination microscopy of tachyzoites suggests that the O-fucosylated proteins form assemblies that localize at the nuclear periphery. AAL: Aleuria aurantia lectin (binds to fucose); IMC3: marker for T. gondii inner membrane complex.

Toxoplasma gondii pentasaccharide was defined as Galα1,3Glcα1,3Fucα1,2Galβ1,3GlcNAcα1- (Gal, Galactose; Glc, Glucose; Fuc, Fucose) based on glycopeptide MS/MS data, NMR studies, and homology to the Dictyostelium biosynthetic pathway (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Zhao, Mandalasi, van der Wel, Wells, Blader and West2016, Reference Rahman, Mandalasi, Zhao, Sheikh, Taujale, Kim, van der Wel, Matta, Kannan, Glushka, Wells and West2017; West and Hart, Reference West, Hart, Varki, Cummings, Esko, Stanley, Hart, Aebi, Darvill, Kinoshita, Packer, Prestegard, Schnaar and Seeberger2017). After hydroxylation of proline 154 by TgPhyA (TGGT1_232960) (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Wang, Green and West2012b), the first glycosyltransferase, TgGnt1 (TGGT1_315885), transfers GlcNAc in an α linkage (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Zhao, Mandalasi, van der Wel, Wells, Blader and West2016), resulting in an alkali-resistant glycosylation (Fig. 2A). Gnt1 belongs to the Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme (CAZy) glycosyltransferase (GT) 60 family (or GT60), a group that includes also Trypanosoma cruzi UDP-GlcNAc: polypeptide α-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (Heise et al., Reference Heise, Singh, van der Wel, Sassi, Johnson, Feasley, Koeller, Previato, Mendonca-Previato and West2009; Lombard et al., Reference Lombard, Golaconda Ramulu, Drula, Coutinho and Henrissat2014). Incubation of DdSkp1 with UDP-[3H]GlcNAc and cytosolic extracts of wild type T. gondii, but not of Δgnt1 parasites, resulted in the transfer of [3H]-GlcNAc to DdSkp1, consistent with the identification of TgGnt1 as the UDP-GlcNAc:HyPro Skp1 polypeptide α-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. This activity is dependent on the presence of PhyA, indicating the specificity of Gnt1 for the hydroxylated proline as acceptor (West et al., Reference West, van der Wel and Blader2006; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Zhao, Mandalasi, van der Wel, Wells, Blader and West2016).

Transfer of the second and third sugars is catalysed by TgPgtA (TTGT1_260650), a bifunctional β1,3-galactosyltransferase (β1,3-GalT)/α1,2-fucosyltransferase (α1,2-FucT) (Fig. 2A). PgtA is organized in two separate domains belonging to the glycosyltransferase family GT74 and GT2, each responsible for one specific glycosyltransferase activity. The GT74 family was founded with D. discoideum PgtA and contains several eukaryotic and bacterial α1,2-FucTs (West et al., Reference West, Wang and van der Wel2010). The GT2 domain of PgtA mediates the transfer of β1,3Gal (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Zhao, Mandalasi, van der Wel, Wells, Blader and West2016) and belongs to a very large family of functionally diverse inverting GTs. TgPgtA presents a GT74-GT2 tandem organization, while the domains are swapped in Dictyostelium PgtA (Van Der Wel et al., Reference Van Der Wel, Fisher and West2002). The same assay setup described above for TgGnt1 was used to demonstrate both FucT and GalT activities from T. gondii cytosolic extracts. Transfer of Fuc required the presence of UDP-Gal in the reaction, but not vice versa, indicating that Gal and Fuc are transferred sequentially to GlcNAcα-O-Skp1 (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Zhao, Mandalasi, van der Wel, Wells, Blader and West2016).

Dictyostelium discoideum and T. gondii Skp1 glycosylation differ in the nature of the two distal sugars. In Dictyostelium, a single glycosyltransferase DdAgtA transfers two α1,3Gal residues (Ercan et al., Reference Ercan, Panico, Sutton-Smith, Dell, Morris, Matta, Gay and West2006; Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Sheikh, Zhang and West2014; Sheikh et al., Reference Sheikh, Thieker, Chalmers, Schafer, Ishihara, Azadi, Woods, Glushka, Bendiak, Prestegard and West2017), while the core trisaccharide of T. gondii Skp1 is sequentially modified with an α1,3Glc and an α1,3Gal added by TgGlt1 and TgGat1, respectively (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Mandalasi, Zhao, Sheikh, Taujale, Kim, van der Wel, Matta, Kannan, Glushka, Wells and West2017; Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019) (Fig. 2A). TgGlt1 (TGGT1_205060), a member of the GT32 family, was identified as a UDP-Glc: fucoside α1,3-glucosyltransferase using multiple approaches. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of immunoprecipitated Skp1 in parasites deficient for glt1 revealed the accumulation of protein modified by the trisaccharide only. Moreover, 1D and 2D NMR analysis of the product obtained with recombinant TgGlt1 showed that the enzyme transferred Glc in an α1,3 linkage (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Mandalasi, Zhao, Sheikh, Taujale, Kim, van der Wel, Matta, Kannan, Glushka, Wells and West2017). Finally, TgGat1 (TGGT1_310400), the last enzyme involved in the pathway, has not yet been extensively characterized. This enzyme is a member of the GT8 family, which comprises retaining UDP-sugar transferases, including glycogenins (Lombard et al., Reference Lombard, Golaconda Ramulu, Drula, Coutinho and Henrissat2014; West and Hart, Reference West, Hart, Varki, Cummings, Esko, Stanley, Hart, Aebi, Darvill, Kinoshita, Packer, Prestegard, Schnaar and Seeberger2017) and a knock-out cell line has just been reported (Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019).

Recent studies in D. discoideum have shed some light on the role of Skp1 glycosylation. Structural and molecular dynamics studies suggested that the pentasaccharide stabilizes the flexible F-box-binding domain on Skp1, favouring an open conformation that improves binding to its ubiquitination partners, e.g. Cullin1 (Sheikh et al., Reference Sheikh, Thieker, Chalmers, Schafer, Ishihara, Azadi, Woods, Glushka, Bendiak, Prestegard and West2017). While key Skp1 amino acids involved in interacting with the pentasaccharide are conserved in T. gondii Skp1, further studies are necessary to understand if the Dictyostelium model extends to this parasite. Furthermore, unlike Dictyostelium that during its development moves between environments with very different oxygen levels, T. gondii spends most of its life cycle in low oxygen (intracellular stages) or anoxia (oocysts released in the intestine) settings (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Brown, Wang, van der Wel, Teygong, Zhang, Blader and West2012a). If this difference is relevant only at the level of post-translational modification kinetics or has a wider importance in the function of this signalling pathway remains to be studied.

O-fucosylation of nucleocytosolic proteins in T. gondii

Immunofluorescence and enrichment using the fucose-specific Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) led to the identification at least 69 O-fucosylated proteins that localize to the nuclear periphery of T. gondii tachyzoites (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Haserick, Motari, Ouologuem, Lourido, Roos, Costello, Robbins and Samuelson2016) (Fig. 2B). Glycopeptide analysis identified amino acids sequences modified with up to 6 deoxyhexoses (dHex) linked to a Ser or Thr residue, and gas chromatography-MS (GC-MS) compositional analysis after reductive β-elimination identified the dHex as Fuc. This was further confirmed by the loss of AAL binding after transient gene disruption of GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase, a key enzyme in GDP-Fucose (GDP-Fuc) biosynthesis (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Haserick, Motari, Ouologuem, Lourido, Roos, Costello, Robbins and Samuelson2016). While no consensus O-fucosylation motif could be identified, the observed peptides are rich in Ser, Thr and non-polar amino acids. In addition, about a third of the identified peptides contain long homoserine repeats.

The identified O-fucosylated proteins have a variety of predicted functions, from nuclear transport and mRNA processing to signalling and protein–protein interactions (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Haserick, Motari, Ouologuem, Lourido, Roos, Costello, Robbins and Samuelson2016) (Fig. 2B). These protein families and modified peptides are highly reminiscent of the sequences modified by the O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) in animals (Bond and Hanover, Reference Bond and Hanover2015). Indeed, the T. gondii genome encodes for a putative OGT (TGGT1_273500), having high homology to SPY-like enzymes (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Robbins and Samuelson2009; Olszewski et al., Reference Olszewski, West, Sassi and Hartweck2010). The SPY-like vs SEC-like classification originates in plants, which were long thought to encode two OGTs: SPINDLY (SPY) and SECRET AGENT (SEC) (Olszewski et al., Reference Olszewski, West, Sassi and Hartweck2010). SPY-like and SEC-like enzymes are both characterized by an N-terminal domain composed of tetratricopeptide repeats and a C-terminal CAZy GT41 catalytic domain (Olszewski et al., Reference Olszewski, West, Sassi and Hartweck2010; Lombard et al., Reference Lombard, Golaconda Ramulu, Drula, Coutinho and Henrissat2014). They differ in the number of tetratricopeptide repeats and the sequence of the GT41 domain (Olszewski et al., Reference Olszewski, West, Sassi and Hartweck2010), even though many catalytic residues are conserved (Zentella et al., Reference Zentella, Sui, Barnhill, Hsieh, Hu, Shabanowitz, Boyce, Olszewski, Zhou, Hunt and Sun2017). Animals and fungi OGTs classify as SEC-like and are involved in O-GlcNAc transfer just as A. thaliana SEC (Hartweck et al., Reference Hartweck, Scott and Olszewski2002). In contrast, AtSPY has recently been shown to be an O-fucosyltransferase (Zentella et al., Reference Zentella, Sui, Barnhill, Hsieh, Hu, Shabanowitz, Boyce, Olszewski, Zhou, Hunt and Sun2017) and not an OGT. Consistent with this report, knock-out of spy in T. gondii resulted in the loss of AAL binding, strongly suggesting the nucleocytosolic O-fucosyltransferase activity of TgSPY. Spy-deficient parasites were viable but displayed a mild defect in replication in host cells in vitro (Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019). Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) showed that AAL binds in a punctate pattern to the nuclear periphery of T. gondii tachyzoites, suggesting that the O-fucosylated proteins are forming assemblies (Fig. 2B). Furthermore a Ser-rich domain fused to YFP is O-fucosylated when expressed in tachyzoites and localizes to the nuclear periphery (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Haserick, Motari, Ouologuem, Lourido, Roos, Costello, Robbins and Samuelson2016). Co-labelling with a Phenylalanine-Glycine (FG)-repeat nucleoporin suggests that these assemblies are found in close proximity to the nuclear pore complex and four out of the six T. gondii FG-repeat nucleoporins are found in the AAL-enriched fraction (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Haserick, Motari, Ouologuem, Lourido, Roos, Costello, Robbins and Samuelson2016; Courjol et al., Reference Courjol, Mouveaux, Lesage, Saliou, Werkmeister, Bonabaud, Rohmer, Slomianny, Lafont and Gissot2017). This pattern was also observed in bradyzoites and sporozoites, but not in oocysts, suggesting that nuclear O-fucosylation might be regulated during the parasite life cycle (Fig. 4).

Nuclear staining with AAL was observed not only in Hammondia hammondi and Neospora caninum, the two species most closely related to T. gondii, but also Cryptosporidum parvum sporozoites (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Haserick, Motari, Ouologuem, Lourido, Roos, Costello, Robbins and Samuelson2016), which are all predicted to encode a SPINDLY orthologue. Interestingly, nucleocytosolic extracts of T. gondii or C. parvum as well as the recombinant C. parvum SPY enzyme have been shown to have OGT activity in vitro (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Robbins and Samuelson2009; Perez-Cervera et al., Reference Perez-Cervera, Harichaux, Schmidt, Debierre-Grockiego, Dehennaut, Bieker, Meurice, Lefebvre and Schwarz2011). Recent work has also reported the presence of O-GlcNAcylated proteins both in P. falciparum and T. gondii, using enrichment of proteins with terminal GlcNAc and identification by MS/MS (Kupferschmid et al., Reference Kupferschmid, Aquino-Gil, Shams-Eldin, Schmidt, Yamakawa, Krzewinski, Schwarz and Lefebvre2017; Aquino-Gil et al., Reference Aquino-Gil, Kupferschmid, Shams-Eldin, Schmidt, Yamakawa, Mortuaire, Krzewinski, Hardiville, Zenteno, Rolando, Bray, Perez Campos, Dubremetz, Perez-Cervera, Schwarz and Lefebvre2018). Unfortunately, the peptide fragmentation technique used in these studies did not allow observation of glycopeptides. Future work will likely address the substrate specificity of SPY protein and its potential implication in O-GlcNAcylation. Work published in A. thaliana so far describes only one protein acceptor for SPY, the master regulator DELLA, which is also a substrate for SEC (Zentella et al., Reference Zentella, Hu, Hsieh, Matsumoto, Dawdy, Barnhill, Oldenhof, Hartweck, Maitra, Thomas, Cockrell, Boyce, Shabanowitz, Hunt, Olszewski and Sun2016, Reference Zentella, Sui, Barnhill, Hsieh, Hu, Shabanowitz, Boyce, Olszewski, Zhou, Hunt and Sun2017). However, no subcellular localization studies have been performed in this system. Further studies will define if O-fucosylation directs proteins at the nuclear periphery and if this role is conserved in other eukaryotic lineages.

Glycosylation of thrombospondin type 1 repeats

In 2015, Cova and colleagues pointed out the conservation of enzymes for GDP-mannose (GDP-Man) and GDP-Fuc biosynthesis in the genome of different apicomplexan parasites (Cova et al., Reference Cova, Rodrigues, Smith and Izquierdo2015). These nucleotides sugars, required for glycosylation reactions, were also shown to be present in Plasmodium falciparum blood stages by LC-MS/MS (Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, Bandini, Ospina, Bernabeu, Marino, Fernandez-Becerra and Izquierdo2013). A substantial pool of GDP-Man was expected since Apicomplexa synthesize abundant GPI-anchors, but the presence of GDP-Fuc was more surprising considering that no fucose-containing glycoconjugates had been identified. The existence of fucosylated proteins in the nucleus and the Skp1 pathway mentioned above would explain the requirement for GDP-Fuc in T. gondii and a few other Apicomplexa, but not in Plasmodium spp. However, several Apicomplexa adhesins have thrombospondin type-1 repeats (TSRs), and homologs of the enzymes required for O-fucosylation and C-mannosylation of TSRs in higher eukaryotes can be identified in this phylum (Buettner et al., Reference Buettner, Ashikov, Tiemann, Lehle and Bakker2013; Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, Bandini, Ospina, Bernabeu, Marino, Fernandez-Becerra and Izquierdo2013; Cova et al., Reference Cova, Rodrigues, Smith and Izquierdo2015).

TSRs are ancient protein modules that emerged before the separation of nematodes and chordates (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Vogel, Plenefisch, Norris, Proenca, Spieth, Guo, Mastwal, Zhu, Scheel and Hedgecock2000). These domains contain approximately 60 amino acids and are typically organized as an elongated three stranded β-sheet, with three conserved disulfide bridges and stacked tryptophan and arginine residues that stabilize the TSR structure (Tan et al., Reference Tan, Duquette, Liu, Dong, Zhang, Joachimiak, Lawler and Wang2002). Present in several proteins in vertebrates, these adhesive domains play roles in immunity, adhesion, neuronal development and signalling (Adams and Tucker, Reference Adams and Tucker2000; Shcherbakova et al., Reference Shcherbakova, Tiemann, Buettner and Bakker2017). In Apicomplexa, the extracellular domains of several adhesins, including Plasmodium thrombospondin-relative anonymous protein (TRAP, PF3D7_1335900), circumsporozoite protein (CSP, PF3D7_0304600), and T. gondii micronemal proteins 2 (MIC2, TGME49_201780) contain at least one TSR domain (Tucker, Reference Tucker2004; Carruthers and Tomley, Reference Carruthers and Tomley2008) (Fig. 3A). These adhesins interact with receptors present at the host cell surface and are linked via their cytoplasmic tail to the glideosome, a molecular machine necessary for parasite motility and host cell invasion (Frenal et al., Reference Frenal, Dubremetz, Lebrun and Soldati-Favre2017). Plasmodium spp. express several TRAP variants that mediate motility, invasion, and egress at different stages of the parasite life cycle, both in the mammalian host and in the mosquito (Sultan et al., Reference Sultan, Thathy, Frevert, Robson, Crisanti, Nussenzweig, Nussenzweig and Menard1997; Dessens et al., Reference Dessens, Beetsma, Dimopoulos, Wengelnik, Crisanti, Kafatos and Sinden1999; Wengelnik et al., Reference Wengelnik, Spaccapelo, Naitza, Robson, Janse, Bistoni, Waters and Crisanti1999; Combe et al., Reference Combe, Moreira, Ackerman, Thiberge, Templeton and Menard2009; Steinbuechel and Matuschewski, Reference Steinbuechel and Matuschewski2009; Bargieri et al., Reference Bargieri, Thiberge, Tay, Carey, Rantz, Hischen, Lorthiois, Straschil, Singh, Singh, Triglia, Tsuboi, Cowman, Chitnis, Alano, Baum, Pradel, Lavazec and Menard2016). In T. gondii, MIC2 plays a comparable role in tachyzoites (Huynh et al., Reference Huynh, Rabenau, Harper, Beatty, Sibley and Carruthers2003; Huynh and Carruthers, Reference Huynh and Carruthers2006; Gras et al., Reference Gras, Jackson, Woods, Pall, Whitelaw, Leung, Ward, Roberts and Meissner2017). In addition, several Apicomplexa TSR-containing proteins are uncharacterized, and their functions remain unknown.

Fig. 3. O-fucosylation and C-mannosylation on TSR repeats. (A) Summary of the mass spectrometry evidence for TSR glycosylation in the two parasites. The presence of a plus sign between Glc and Fuc indicates that glycopeptides were observed for two different glycoforms: only dHex (Fuc) or Hex-dHex (FucGlc). (B) Schematic representation of the two TSR glycosylation pathways in T. gondii. DPY19 transfers Man from dolichol-phosphate-mannose to tryptophan (W) residues on TSRs. POFUT2, a soluble protein in most eukaryotes, modifies Ser/Thr in the CX2−3S/TCX2G motif with Fuc, which can be further elongated by addition of Glc by B3GLCT. This glycosylation requires the GDP-Fuc transporter NST2 and a UDP-Glc transporter. (C) In P. falciparum, POFUT2 and DPY19 are known to modify TSRs with O-Fuc and C-Man, as detailed for Toxoplasma. The identities of the B3GLCT and the Hex transferred on Fuc have not yet been ascertained. NST2 is the predicted GDP-Fuc transporter.

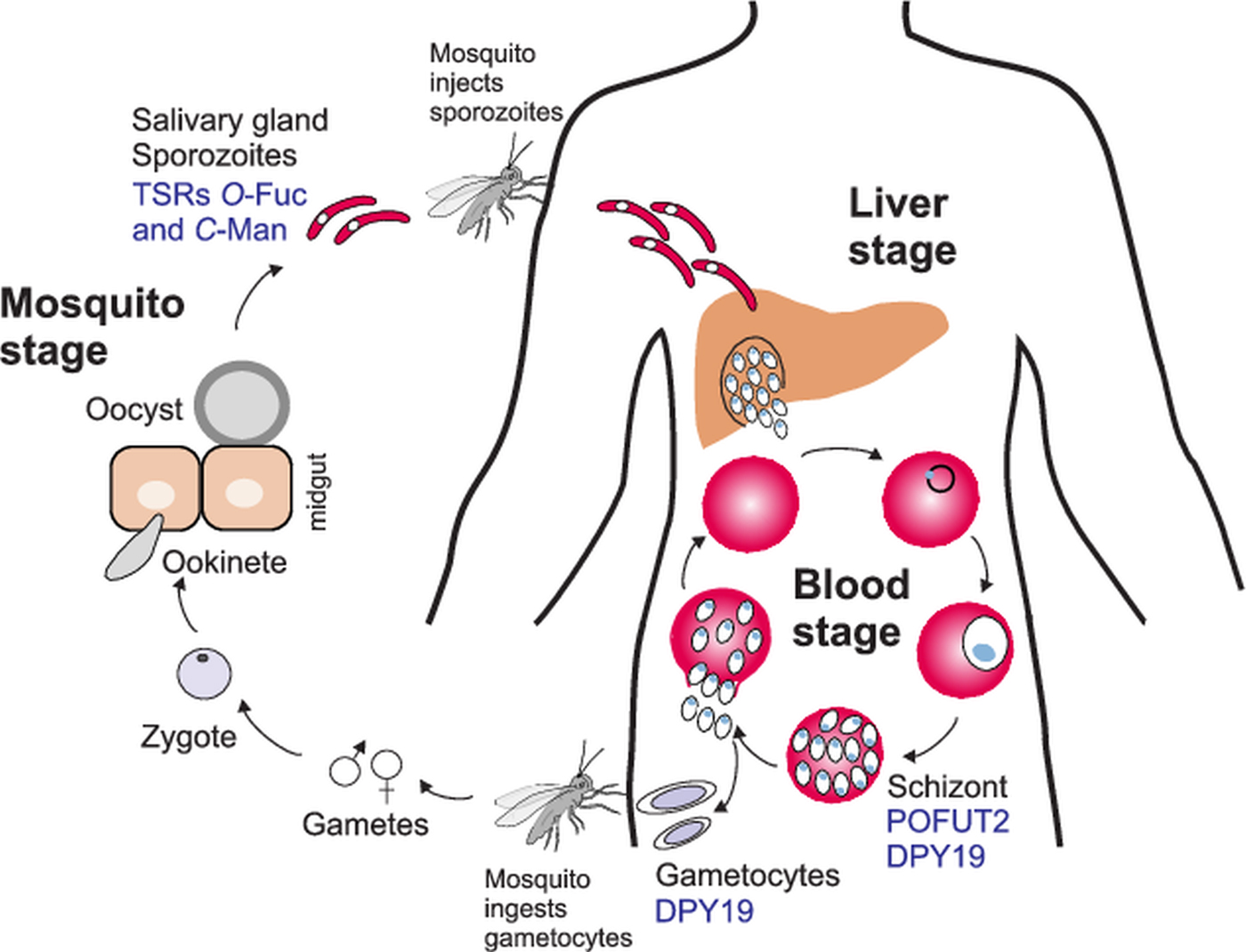

O-fucosylation

Besides database mining, the presence of α-O-fucosylation in Apicomplexa was strongly suggested by MS/MS analyses of TRAP and CSP from P. falciparum sporozoites, which demonstrated modification of the TSRs by an O-linked hexose-deoxyhexose (Hex-dHex) (Swearingen et al., Reference Swearingen, Lindner, Shi, Shears, Harupa, Hopp, Vaughan, Springer, Moritz, Kappe and Sinnis2016) (Fig. 3A). This disaccharide was assumed to be Glcβ1,3Fuc-α-O-Ser/Thr as described in mammalian TSRs (Kozma et al., Reference Kozma, Keusch, Hegemann, Luther, Klein, Hess, Haltiwanger and Hofsteenge2006; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Koles, Vorndam, Haltiwanger and Panin2006; Vasudevan and Haltiwanger, Reference Vasudevan and Haltiwanger2014). A clear homolog of the protein O-fucosyltransferase 2 (POFUT2) could indeed be identified in the genome of apicomplexan parasites (Cova et al., Reference Cova, Rodrigues, Smith and Izquierdo2015). POFUT2 catalyses α-linked fucosylation of Ser or Thr residues in the consensus sequence C1X2−3S/TC2X2G, where C1 and C2 are the first two conserved cysteines in the TSR (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Koles, Vorndam, Haltiwanger and Panin2006). The ability of recombinant Plasmodium vivax POFUT2 (PVX_098900) to use GDP-Fuc as donor substrate and to modify the CX2−3S/TCX2G motif of TRAP and CSP was later demonstrated using an in vitro glycosyltransferase assay (Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017). In T. gondii, MIC2 is intensely stained with an antibody recognizing the Glcβ1,3Fuc epitope, and four TSRs of MIC2 that contain an O-fucosylation motif (TSR1, 3, 4 and 5) are modified by a Hex-dHex disaccharide by MS/MS analysis of glycopeptides (Fig. 3A). This modification was abolished by deletion of the gene encoding POFUT2 (TGME49_273550) thereby proving the function of this glycosyltransferase in T. gondii (Fig. 3B) (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Leon, Hoppe, Zhang, Agop-Nersesian, Shears, Mahal, Routier, Costello and Samuelson2019; Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019; Khurana et al., Reference Khurana, Coffey, John, Uboldi, Huynh, Stewart, Carruthers, Tonkin, Goddard-Borger and Scott2019).

Deletion of the gene encoding POFUT2 in P. falciparum (PF3D7_0909200) and, in at least one report, in T. gondii indicates that, in apicomplexa as in mammals, O-fucosylation plays a role in the stabilization and trafficking of TSR-containing proteins (Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017; Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Leon, Hoppe, Zhang, Agop-Nersesian, Shears, Mahal, Routier, Costello and Samuelson2019). As in mammals, the loss of α-O-fucosylation affected proteins differently. In Plasmodium sporozoites, the cellular level of TRAP was significantly decreased, whereas CSP was not affected (Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017). Consistent with the importance of TRAP in adhesion and motility, hepatocyte invasion by sporozoites was impaired leading to a reduced liver parasite load. Loss of O-fucosylation also impacted on infection of mosquito midgut epithelial cells by ookinetes (Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017). This phenotype could be related to a destabilization of the circumsporozoite and TRAP-related protein (CTRP, PF3D7_0315200), since this protein is involved in the motility of ookinetes and contains O-fucosylation motifs (Dessens et al., Reference Dessens, Beetsma, Dimopoulos, Wengelnik, Crisanti, Kafatos and Sinden1999; Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017). However, several other proteins contain the CX2S/TCX2G motif and might contribute to the phenotype observed in POFUT2-deficient parasites. In blood stage parasites, POFUT2 is expressed but dispensable for growth (Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, Bandini, Ospina, Bernabeu, Marino, Fernandez-Becerra and Izquierdo2013; Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017). Similarly, no prominent effects were observed in the blood stages of P. falciparum and P. berghei mutants lacking enzymes involved in GDP-Fuc biosynthesis (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Bushell, Schwach, Girling, Anar, Quail, Herd, Pfander, Modrzynska, Rayner and Billker2015; Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, Lopez-Gutierrez, Bandini, Damerow, Absalon, Dinglasan, Samuelson and Izquierdo2016). To date, no O-fucosylated protein has been identified in blood stages. The TSR-containing TRAP variants MTRAP (merozoite TRAP), SPATR (sporozoite protein with an altered thrombospondin repeat) and PTRAMP (Plasmodium thrombospondin-related apical merozoite protein) are devoid of the canonical POFUT2 consensus motif, suggesting that they are not O-fucosylated (Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017).

As in Plasmodium, deletion of T. gondii POFUT2 affects the trafficking and cellular levels of the major parasite adhesin MIC2. Using in vitro assays, the decreased adhesion and impaired ability to invade displayed by POFUT2-deficient parasites were comparable to those observed in a mutant completely devoid of MIC2 (Gras et al., Reference Gras, Jackson, Woods, Pall, Whitelaw, Leung, Ward, Roberts and Meissner2017; Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Leon, Hoppe, Zhang, Agop-Nersesian, Shears, Mahal, Routier, Costello and Samuelson2019). However, the defects in both egress and parasite replication were much less pronounced in the O-fucosylation mutant than in the parasites lacking MIC2. Add back of pofut2 rescued the attachment/invasion phenotype of Δpofut2 parasites and restored cellular MIC2 levels, ruling out off-target mutations being the cause of the phenotype in the knockout. An identical phenotype was obtained by deletion of the nucleotide sugar transporter 2 (NST2, TGGT1_267730) establishing the specificity of this transporter for GDP-Fuc (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Leon, Hoppe, Zhang, Agop-Nersesian, Shears, Mahal, Routier, Costello and Samuelson2019) (Fig. 3B). Toxoplasma gondii pofut2 was knocked out in two additional studies (Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019; Khurana et al., Reference Khurana, Coffey, John, Uboldi, Huynh, Stewart, Carruthers, Tonkin, Goddard-Borger and Scott2019). Gas-Pascual et al., reported a defect in parasite replication upon its disruption, but did not address invasion or attachment as it was beyond the scope of the screen performed in this study. Finally, in Khurana et al., knock-out of pofut2 had no effect on cellular levels of MIC2, parasite proliferation, or its ability to attach and invade host cells. Discrepant phenotypes between the two reported pofut2 knockouts likely results from the different methods used for generating these cell lines and/or for assaying phenotype (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Leon, Hoppe, Zhang, Agop-Nersesian, Shears, Mahal, Routier, Costello and Samuelson2019; Khurana et al., Reference Khurana, Coffey, John, Uboldi, Huynh, Stewart, Carruthers, Tonkin, Goddard-Borger and Scott2019).

In mammals, O-linked fucose on TSRs is typically extended by a β1,3-linked glucose transferred by the glucosyltransferase B3GLCT, which is also involved in protein quality control (Kozma et al., Reference Kozma, Keusch, Hegemann, Luther, Klein, Hess, Haltiwanger and Hofsteenge2006; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Koles, Vorndam, Haltiwanger and Panin2006). A recent study indicates that a small percentage of TRAP and CSP from P. falciparum salivary glands sporozoites is modified with a Hex-dHex whereas only a dHex is found on these proteins in P. vivax and P. yoelii sporozoites (Swearingen et al., Reference Swearingen, Eng, Shteynberg, Vigdorovich, Springer, Mendoza, Sather, Deutsch, Kappe and Moritz2019). This glucosyltransferase belongs to the large GT31 family, which contains enzymes with various functions (Lombard et al., Reference Lombard, Golaconda Ramulu, Drula, Coutinho and Henrissat2014). In P. falciparum, the parasite-infected erythrocyte surface protein 1 (PIESP1, PF3D7_0310400) shares 31% protein identity with the human B3GLCT and has been proposed as candidate B3GLCT (Swearingen et al., Reference Swearingen, Lindner, Shi, Shears, Harupa, Hopp, Vaughan, Springer, Moritz, Kappe and Sinnis2016). Surprisingly, this protein was localized at the surface of infected red blood cells (Florens et al., Reference Florens, Liu, Wang, Yang, Schwartz, Peglar, Carucci, Yates and Wu2004), whereas B3GLCT would be expected to localize in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with POFUT2 (Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017). Moreover, by saturation mutagenesis, the PF3D7_0310400 gene is predicted to be essential in asexual blood stages whereas pofut2 is dispensable (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Otto, Oberstaller, Liao, Adapa, Udenze, Bronner, Casandra, Mayho, Brown, Li, Swanson, Rayner, Jiang and Adams2018). These data suggest that PIESP1 is not responsible for glucosylation of O-fucose. In T. gondii, however, Gas-Pascual and colleagues recently reported loss of an O-linked Hex-dHex disaccharide upon knock-out of the putative b3gltc (TGGT1_239752) indicating that this enzyme is likely responsible for elongating O-Fuc (Fig. 3B). A defect in the lytic cycle characterised by small lytic plaques was also reported in this mutant (Gas-Pascual et al., Reference Gas-Pascual, Ichikawa, Sheikh, Serji, Deng, Mandalasi, Bandini, Samuelson, Wells and West2019). While binding of MIC2 by a Glcβ1,3Fuc-specific antibody suggests that at least in T. gondii the hexose modifying O-Fuc is indeed Glc (Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Leon, Hoppe, Zhang, Agop-Nersesian, Shears, Mahal, Routier, Costello and Samuelson2019), further investigations are necessary to confirm this result and the identity of the hexose in other Apicomplexa.

Nucleotide sugars, required for the biosynthesis of glycans, are mostly synthesized in the cytosol and actively transported into the ER or Golgi by the action of nucleotide sugar /nucleoside monophosphate antiporters (NSTs). The functional identification of TgNST2, the GDP-fucose transporter in T. gondii, has been mentioned above and P. falciparum genome also encodes a putative GDP-sugar transporter, PF3D7_0212000 (Fig. 3C). Similarly, B3GLCT activity requires transport of the UDP-glucose donor into the ER. Bioinformatics searches, using either yeast or human NSTs as templates, identified T. gondii NST3 (TGGT1_254580) and PfUGT (PF3D7_1113300) as putative UDP-Glc/UDP-Gal transporters because of their close homology with the yeast HUT1 transporter (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Cui, Robbins and Samuelson2008; Caffaro et al., Reference Caffaro, Koshy, Liu, Zeiner, Hirschberg and Boothroyd2013). In Plasmodium erythrocyte stages, PfUGT has been localized to the ER and identified as a multidrug resistance gene (Lim et al., Reference Lim, LaMonte, Lee, Reimer, Tan, Corey, Tjahjadi, Chua, Nachon, Wintjens, Gedeck, Malleret, Renia, Bonamy, Ho, Yeung, Chow, Lim, Fidock, Diagana, Winzeler and Bifani2016). Using a CRISPR screen, the phenotype score associated with the TgNST3 encoding gene (−4.9) was significantly lower than the scores associated with pofut2 (−0.34) and b3glct (−1.36) suggesting that deletion of nst3 would have much more severe effects than the loss of O-fucosylation (Sidik et al., Reference Sidik, Hackett, Tran, Westwood and Lourido2014). Similarly, piggyBac transposon insertional mutagenesis suggests that the gene encoding the putative UDP-Glc/UDP-Gal transporter PfUGT is not mutable in asexual blood stages whereas, as mentioned above, O-fucosylation does not seem to play important roles in these parasite stages (Lopaticki et al., Reference Lopaticki, Yang, John, Scott, Lingford, O'Neill, Erickson, McKenzie, Jennison, Whitehead, Douglas, Kneteman, Goddard-Borger and Boddey2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Otto, Oberstaller, Liao, Adapa, Udenze, Bronner, Casandra, Mayho, Brown, Li, Swanson, Rayner, Jiang and Adams2018). These results are difficult to conciliate and suggest that TgNST3 and PfUGT have a different or broader substrate specificity. In metazoans, the function of the HUT1 transporter is also still unclear. Recently, the human orthologue called solute carrier 35B1 (SLC35B1), has been proposed to act as ATP/ADP antiporter (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Zimmermann, Schorr, Landini, Klemens, Altensell, Jung, Krause, Nguyen, Helms, Rettig, Fecher-Trost, Cavalie, Hoth, Bogeski, Neuhaus, Zimmermann, Lang and Haferkamp2018).

C-mannosylation

C-mannosylation is a less known protein modification, mediated by enzymes of the DPY19 family, which, in metazoans, transfer an α-mannose residue from dolichol-phosphate-mannose to a tryptophan (Trp) residue located in a WX2W or WX2C motif (Buettner et al., Reference Buettner, Ashikov, Tiemann, Lehle and Bakker2013; Niwa et al., Reference Niwa, Suzuki, Dohmae and Simizu2016; Shcherbakova et al., Reference Shcherbakova, Tiemann, Buettner and Bakker2017). As in the case of α-O-fucosylation, analysis of Apicomplexa genomes strongly suggested the existence of this modification, and MS/MS analyses confirmed C-hexosylation of tryptophan residues in the TSRs of Plasmodium TRAP and Toxoplasma MIC2, in sporozoites and tachyzoites, respectively (Figs 3A, 4 and 5) (Swearingen et al., Reference Swearingen, Lindner, Shi, Shears, Harupa, Hopp, Vaughan, Springer, Moritz, Kappe and Sinnis2016, Reference Swearingen, Eng, Shteynberg, Vigdorovich, Springer, Mendoza, Sather, Deutsch, Kappe and Moritz2019; Bandini et al., Reference Bandini, Leon, Hoppe, Zhang, Agop-Nersesian, Shears, Mahal, Routier, Costello and Samuelson2019; Khurana et al., Reference Khurana, Coffey, John, Uboldi, Huynh, Stewart, Carruthers, Tonkin, Goddard-Borger and Scott2019). In metazoans, this glycosylation is typically found on TSRs carrying a WX2WX2C1 sequence (that directly precedes the O-fucosylation site), as well as type I cytokine receptors characterized by a WSXWS signature (Hofsteenge et al., Reference Hofsteenge, Blommers, Hess, Furmanek and Miroshnichenko1999; Julenius, Reference Julenius2007). However, the latter is not found in Apicomplexa. In mammals, two different enzymes (DPY19L1 and DPY19L3) are required for C-mannosylation of both Trp residues in the sequence WX2WX2C, whereas Apicomplexa genomes contain a single DPY19 homolog (Buettner et al., Reference Buettner, Ashikov, Tiemann, Lehle and Bakker2013; Shcherbakova et al., Reference Shcherbakova, Tiemann, Buettner and Bakker2017). An in vitro assay using recombinant T. gondii (TGME49_080400) and P. falciparum DPY19 (PF3D7_0806200) indicated that the apicomplexan enzymes are unable to act on a WX2W peptide as their mammalian counterparts but modified WX2WX2C motif, suggesting that they are tailored for TSR modification. Detailed MS/MS analyses of MIC2 further indicated that both tryptophans of the WX2WX2C sequence can be modified (Fig. 3A). Finally, in vitro assays also showed that both T. gondii and P. falciparum DPY19 use dolichol-phosphate-mannose as donor substrate, proving their mannosyltransferase activity (Hoppe et al., Reference Hoppe, Albuquerque-Wendt, Bandini, Leon, Shcherbakova, Buettner, Izquierdo, Costello, Bakker and Routier2018).

Fig. 4. O- and C-glycosylation pathways in Toxoplasma gondii life cycle. T. gondii replicates asexually in the intermediate host with tachyzoites as the fast replicative form and bradyzoites in tissue cysts characterizing the chronic stage of infection. In felids, its definite host, T. gondii goes through a sexual cycle that concludes with the shedding of unsporulated oocysts that then sporulate in the environment. As shown in the schematic, all the glycosylation pathways reviewed here have been shown to be present in tachyzoites. Transfer of O-GalNAc to mucin-like domains is an important post-translational modification in tissue cyst wall proteins and pp-GalNAcT5 is expressed in oocysts. Nuclear O-fucosylation has been shown to be present also in bradyzoites and sporozoites, but is absent from oocysts.

Fig. 5. O- and C-glycosylation pathways in Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. During a mosquito blood meal, sporozoites are injected in the bloodstream and infect the liver. After asexual replication in hepatocytes, the parasites are released into the bloodstream where they replicate in erythrocytes to give the characteristic fever symptoms. A fraction of the parasites will develop into gametocytes that can be transmitted to the mosquito during a blood meal. After zygote formation, Plasmodium ookinetes infect the mosquito midgut and develop into oocysts. Sporozoites are released from the oocysts and travel to the salivary gland ready for a new infection cycle. O-fucosylation and C-mannosylation of TSRs have been demonstrated in sporozoites, but POFUT2 and DPY-19 have been detected in the asexual blood stages. DPY19 is also present in gametocytes. Studies on GDP-Fuc biosynthesis have been performed in the intraerythrocytic stages.

In mammals, C-mannosylation is suggested to play an important role in stabilization and/or folding of some but not all proteins (Munte et al., Reference Munte, Gade, Domogalla, Kremer, Kellner and Kalbitzer2008; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Leonhard-Melief, Haltiwanger and Apte2009; Buettner et al., Reference Buettner, Ashikov, Tiemann, Lehle and Bakker2013; Sasazawa et al., Reference Sasazawa, Sato, Suzuki, Dohmae and Simizu2015; Siupka et al., Reference Siupka, Hamming, Kang, Gad and Hartmann2015; Fujiwara et al., Reference Fujiwara, Kato, Niwa, Suzuki, Tsuchiya, Sasazawa, Dohmae and Simizu2016; Niwa et al., Reference Niwa, Suzuki, Dohmae and Simizu2016; Okamoto et al., Reference Okamoto, Murano, Suzuki, Uematsu, Niwa, Sasazawa, Dohmae, Bujo and Simizu2017; Shcherbakova et al., Reference Shcherbakova, Tiemann, Buettner and Bakker2017). Using a CRISPR/Cas9 genetic screen or a piggyBac transposon insertional mutagenesis, DPY19 was predicted to confer fitness to T. gondii tachyzoites or P. falciparum asexual stages, respectively (Sidik et al., Reference Sidik, Hackett, Tran, Westwood and Lourido2014; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Otto, Oberstaller, Liao, Adapa, Udenze, Bronner, Casandra, Mayho, Brown, Li, Swanson, Rayner, Jiang and Adams2018). Further studies are required to define the function of this type of protein glycosylation in apicomplexa.

Concluding remarks

The adaptation of Apicomplexa to parasitic lifestyle was accompanied by a reductive genome evolution involving lineage-specific gene loss (Templeton et al., Reference Templeton, Iyer, Anantharaman, Enomoto, Abrahante, Subramanian, Hoffman, Abrahamsen and Aravind2004). This has led to divergent protein glycosylation in the various Apicomplexa genera. Biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositols is conserved throughout the eukaryotes and these are particularly abundant at the surface of Apicomplexa. In contrast, biosynthetic pathways involved in surface protein N- and O-glycosylation have been considerably reduced or even eliminated. Due to secondary loss of alg genes, Plasmodium expresses rudimentary N-glycans composed of only one or two N-acetylglucosamine residues, whereas Toxoplasma N-glycans are more elaborated (Bushkin et al., Reference Bushkin, Ratner, Cui, Banerjee, Duraisingh, Jennings, Dvorin, Gubbels, Robertson, Steffen, O'Keefe, Robbins and Samuelson2010; Samuelson and Robbins, Reference Samuelson and Robbins2015).

The synthesis of mucin-type O-glycosylation represents another important divergence between Plasmodium and Toxoplasma. Recent genetic and biochemical work clearly established the existence of mucin-type glycosylation in Toxoplasma and its importance for the rigidity of the cyst wall and parasite persistence. These O-GalNAc glycans likely consist of a disaccharide and are thus less complex than in other eukaryotes. Conversely, Plasmodium apparently lacks the enzymes involved in this protein post-translational modification.

Additionally, two distinct cytoplasmic and nuclear glycosylation pathways were recently described in Toxoplasma. The ubiquitin ligase adaptor Skp1 was shown to be hydroxylated and modified by a pentasaccharide; a post-translation modification required for optimal oxygen-dependent development. Lastly, more than 60 Toxoplasma nuclear proteins were shown to be substituted by one or more fucose residues. This modification carried out by the SPY enzyme is reminiscent of protein O-GlcNAcylation and might have a role in localizing proteins at the nuclear periphery. Within the Apicomplexa, these two pathways seem restricted to a few species closely related to Toxoplasma.

In contrast, both Toxoplasma and Plasmodium possess conserved C-mannosylation and O-fucosylation pathways for modification of TSRs. These repeats are present in key surface adhesins and are possibly acquired by horizontal transfer from an animal source. As in animals, C-mannosylation and O-fucosylation of TSR occur in the early secretory pathway and seem to stabilize these repeats.

The presence of simple O- and C-glycans in Apicomplexans proteins has now been clearly established (Figs 4 and 5). Future work will likely clarify the nature of the proteins carrying these modifications and explore the importance of glycosylation for the parasite biology and pathogenicity.

Author ORCIDs

Giulia Bandini, 0000-0002-8885-3643; Françoise H. Routier, 0000-0002-7163-0590

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Carolina Agop-Nersesian for the use of the mosquito and tachyzoite schematic drawings and for critical reading of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the European Community Initial training network GlycoPar (EU FP7, GA. 608295) to F.H.R., a Mizutani Foundation for Glycoscience grant (No. 180117) to G.B. and an NIH grant (R01 AI110638) to J.S. The work of A.A.-W. was performed in partial fulfilment of her PhD thesis carried out in the MD/PhD Molecular Medicine program within the framework of the Hannover Biomedical Research School.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.