INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), is regarded as the world's most successful pathogen (Hingley-Wilson et al. Reference Hingley-Wilson, Sambandamurthy and Jacobs2003). Responsible for an estimated 1·4 million deaths and 10·4 million new cases of TB, including 480 000 new cases of multi-drug resistant (MDR)-TB in 2015 (World Health Organization, 2016), Mtb remains a global health emergency as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization, 2014). New chemotherapeutic agents to complement or replace existing front-line treatment regimens are urgently required to reduce treatment time (currently 6-month course) and to combat the increasing threat by this microorganism.

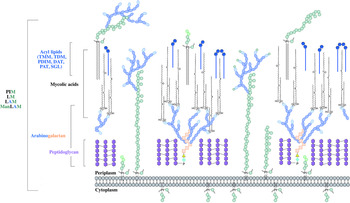

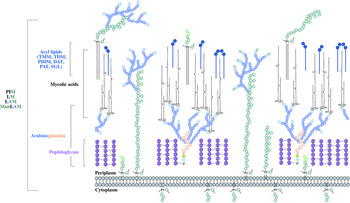

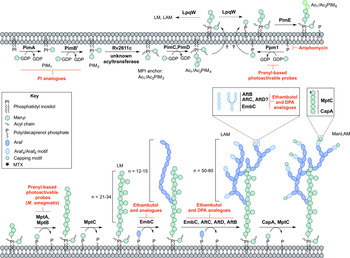

The distinguishing feature of mycobacteria, the complex cell wall, is a well-recognized drug target. The cell wall is common to all bacteria, both Gram-positive and Gram-negative, but can have vast differences in terms of the biochemical and structural features. Over the past decade, extensive research into cell wall assembly, aided by whole-genome sequencing, has led to an increased understanding of mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis. This has promoted further exploration into the discovery and development of chemotherapeutic agents (from an enzymatic and phenotypic perspective) directed against the synthesis of this unique macromolecule structure in Mtb. The Mtb cell envelope is an expansive structure and is summarized in Fig. 1. The inner membrane phospholipid bilayer contains glycolipids that extend into the periplasmic space. The essential core cell wall structure is composed of three main components: a cross-linked polymer of peptidoglycan, a highly branched arabinogalactan polysaccharide, and long-chain mycolic acids. Intercalated into the mycolate layer are solvent-extractable lipids including non-covalently linked glycophospholipids and inert waxes, forming the outer membrane. The capsule forms the outermost layer and is mainly composed of proteins and polysaccharides. The lipid- and carbohydrate-rich layers of the cell wall serve not only as a permeability barrier, providing protection against hydrophilic compounds, but also are critical in pathogenesis and survival. It is these traits that make the biosynthesis and assembly of the cell wall components attractive drug targets. This review focuses on the synthesis of the key cell wall components, highlighting previously validated targets and the ongoing drug discovery efforts to inhibit other essential enzymes in mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis.

Fig. 1. The mycobacterial cell wall. A schematic representation of the mycobacterial cell wall, depicting the prominent features, including the glycolipids (PIMs, phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides; LM, lipomannan; LAM, lipoarabinomannan; ManLAM, mannosylated lipoarabinomannan), peptidoglycan, arabinogalactan and mycolic acids. Intercalated into the mycolate layer are the acyl lipids (including TMM, trehalose monomycolate; TDM, trehalose dimycolate; DAT, diacyltrehalose; PAT, polyacyltrehalose; PDIM, phthiocerol dimycocerosate; SGL, sulfoglycolipid). The capsular material is not illustrated.

PEPTIDOGLYCAN

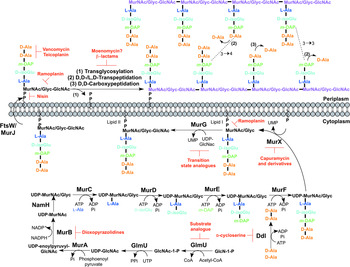

Peptidoglycan is a major component of the cell wall of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Vollmer et al. Reference Vollmer, Blanot and de Pedro2008). It is a polymer of alternating N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid residues via β(1 → 4) linkages with side chains of amino acids cross-linked by transpeptide bridges (Brennan and Nikaido, Reference Brennan and Nikaido1995). Mycobacterial peptidoglycan has a number of unique features that diversifies the cell wall from the typical structure including N-glycolyl- and N-acetyl-muramic acid residues (Mahapatra et al. Reference Mahapatra, Scherman, Brennan and Crick2005a ), amidation of the carboxylic acids in the peptide stems (Mahapatra et al. Reference Mahapatra, Yagi, Belisle, Espinosa, Hill, McNeil, Brennan and Crick2005b ) and additional glycine or serine residues (Vollmer et al. Reference Vollmer, Blanot and de Pedro2008). The function of peptidoglycan is not only to provide shape and rigidity, but it is responsible for counteracting turgor pressure and hence it is essential for growth and survival (Vollmer et al. Reference Vollmer, Blanot and de Pedro2008). Peptidoglycan is unique to bacterial cells, and it is this property that has led to numerous enzymes involved in its synthesis to be targeted by potent antibiotics, with others representing attractive targets in the development of future antibiotics.

PEPTIDOGLYCAN BIOSYNTHESIS

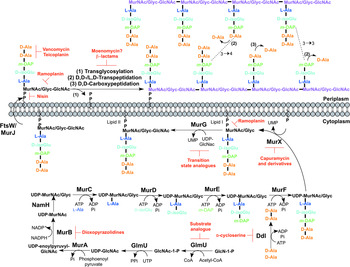

The biosynthesis of peptidoglycan is summarized in Fig. 2. The first committed step is the generation of uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc). This is catalysed by the acetyltransferase and uridyltransferase activities of GlmU (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Bulloch, Bunker, Baker and Squire2009), where first the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA is transferred to glucosamine-1-phosphate (GlcN-1-P) to produce N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate (GlcNAc-1-P). Secondly, uridine-5′-monophosphate from UTP is transferred to GlcNAc-1-P to yield UDP-GlcNAc (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Bulloch, Bunker, Baker and Squire2009). The abundance of GlcNAc-1-P in eukaryotes (Mio et al. Reference Mio, Yabe, Arisawa and Yamada-Okabe1998) and the functional similarity of the GlmU uridyltransferase with human enzymes (Peneff et al. Reference Peneff, Ferrari, Charrier, Taburet, Monnier, Zamboni, Winter, Harnois, Fassy and Bourne2001) makes this domain an unsuitable drug target (Rani and Khan, Reference Rani and Khan2016). However, the absence of GlcN-1-P from humans makes the acetyltransferase domain a potential target (Mio et al. Reference Mio, Yabe, Arisawa and Yamada-Okabe1998). Efforts to identify inhibitors of this domain are underway (Tran et al. Reference Tran, Wen, West, Baker, Britton and Payne2013). A substrate analogue of GlcN-1-P has been designed and exhibits inhibitory effect against GlmU, providing a candidate for further optimization (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhou, Ma and Li2011).

Fig. 2. Inhibitors targeting peptidoglycan biosynthesis. The roles of the key enzymes involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis are illustrated. Reported inhibitors are shown in red.

The next step involves the generation of the UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid (UDP-MurNAc)-pentapeptide, which is synthesized in a sequential pathway catalysed by the Mur ligases A–F (Barreteau et al. Reference Barreteau, Kovac, Boniface, Sova, Gobec and Blanot2008), whereby most of the Mtb genes have been found through homology. MurA, a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase, and MurB, a UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvoylglucosamine reductase, are involved in generating UDP-MurNAc from UDP-GlcNAc, by first the addition of the enoylpyruvyl moiety of PEP, followed by reduction to a lactoyl ether moiety via NADPH. At this point, NamH, a UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid hydroxylase, hydroxylates UDP-MurNAc to UDP-N-glycolylmuramic acid (UDP-MurNGlyc), providing both types of UDP-muramyl substrates; Mtb cell walls are dominated by the latter (Mahapatra et al. Reference Mahapatra, Scherman, Brennan and Crick2005a ). This structural modification is unique to mycobacteria (and closely related genera) and is considered to increase the intrinsic strength of peptidoglycan, by potentially alleviating susceptibility to lysozyme and providing sites for additional hydrogen bonding (Raymond et al. Reference Raymond, Mahapatra, Crick and Pavelka2005). Inhibitors of Mtb MurA and MurB are yet to be discovered. Whilst the natural product, broad spectrum antibiotic, fosfomycin, targets Gram-negative MurA, the critical residue for inhibition is absent in Mtb, providing intrinsic resistance against this antibiotic (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Lees, Kempsell, Lane, Duncan and Walsh1996). Consequently, an inhibitor with a new mode of action is required to target Mtb MurA. A limited number of inhibitors have been reported against MurB. Molecular dynamics and docking studies of existing MurB inhibitors (3,5-dioxopyrazolidine derivatives) onto the Mtb MurB structure reveal the potential potent activity of these compounds, which can be used to guide future structure-based drug design (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Saravanan, Arvind and Mohan2011). Inhibitors of NamH have not been documented; namH is not essential in Mycobacterium smegmatis, and therefore is not condusive to a characteristic target property. However, gene deletion results in a strain hypersusceptible to β-lactam antibiotics and lysozyme and therefore inhibitors of NamH could potentiate the effect of β-lactams (Raymond et al. Reference Raymond, Mahapatra, Crick and Pavelka2005).

The pentapeptide chain is incorporated onto the UDP-MurNAc/Glyc substrates by the successive addition of amino acid residues L-alanine, D-isoglutamate, meso-diaminopimelate (m-DAP) and D-alanyl-D-alanine [generated by the D-Ala: D-Ala ligase (Ddl)] by the ATP-dependent Mur ligases C-F respectively (Munshi et al. Reference Munshi, Gupta, Evangelopoulos, Guzman, Gibbons, Keep and Bhakta2013). This results in the muramyl-pentapeptide product, UDP-MurNAc/Glyc-L-Ala-D-isoGlu-m-DAP-D-Ala-D-Ala, also known as Park's nucleotide (Kurosu et al. Reference Kurosu, Mahapatra, Narayanasamy and Crick2007). Despite the different amino acid specificities, the four ligases share common properties: the reaction mechanism; six invariant ‘Mur’ residues; an ATP-binding consensus; three-dimensional structural domains (Barreteau et al. Reference Barreteau, Kovac, Boniface, Sova, Gobec and Blanot2008). Due to these similarities, it is plausible that a single inhibitor could target more than one Mur ligase and such inhibitors have been reported in the literature (Tomasic et al. Reference Tomasic, Zidar, Kovac, Turk, Simcic, Blanot, Muller-Premru, Filipic, Grdadolnik, Zega, Anderluh, Gobec, Kikelj and Peterlin Masic2010). Numerous small molecule inhibitors of the Mur ligases have been discovered and are the subject of an extensive review (Hrast et al. Reference Hrast, Sosic, Sink and Gobec2014). In most cases, the inhibitors were identified from high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns of compound libraries employing in vitro kinetic assays. These types of in vitro screening methods are limited in use against Mtb Mur ligases given that only MurC and MurE have been biochemically characterized (Mahapatra et al. Reference Mahapatra, Crick and Brennan2000; Li et al. Reference Li, Zhou, Ma and Li2011). This dictates the next rational step towards the target-based discovery of Mur ligase inhibitors. Ddl is the target of D-cycloserine (Bruning et al. Reference Bruning, Murillo, Chacon, Barletta and Sacchettini2011), a second-line drug used in the treatment of TB, and is at the cornerstone of treatment for MDR and extensively drug resistant (XDR)-TB. D-cycloserine acts as a structural analogue of D-Ala, inhibiting the binding of either D-Ala to Ddl (Prosser and de Carvalho, Reference Prosser and de Carvalho2013a , Reference Prosser and de Carvalho b ).

The first membrane-anchored peptidoglycan precursor is generated by the translocation of Park's nucleotide to decaprenyl phosphate (C50-P), catalysed by MurX (also known as MraY), forming Lipid I (Kurosu et al. Reference Kurosu, Mahapatra, Narayanasamy and Crick2007). There are a number of nucleoside-based complex natural products that inhibit MurX, including muraymycin, liposidomycin, caprazamycin and capuramycin (Dini, Reference Dini2005). Capuramycin and derivatives exhibit killing in vitro and in vivo and more significantly, analogues of capuramycin have been shown to kill non-replicating Mtb, a feature not common to the majority of cell wall biosynthesis inhibitors (Koga et al. Reference Koga, Fukuoka, Doi, Harasaki, Inoue, Hotoda, Kakuta, Muramatsu, Yamamura, Hoshi and Hirota2004; Reddy et al. Reference Reddy, Einck and Nacy2008; Nikonenko et al. Reference Nikonenko, Reddy, Protopopova, Bogatcheva, Einck and Nacy2009; Siricilla et al. Reference Siricilla, Mitachi, Wan, Franzblau and Kurosu2015). Significantly, the analogue SQ641 is in preclinical development (http://www.newtbdrugs.org).

The final intracellular step of peptidoglycan synthesis is performed by the glycosyltransferase, MurG. A β(1 → 4) linkage between GlcNAc (from UDP-GlcNAc) and MurNAc/Glyc of Lipid I is formed, leading to the generation of Lipid II, the monomeric building block of peptidoglycan (Mengin-Lecreulx et al. Reference Mengin-Lecreulx, Texier, Rousseau and van Heijenoort1991). A library of transition state mimics have been designed for Escherichia coli MurG, and tested against Mtb MurG with partial success, one being the first inhibitor identified against the Mtb enzyme (Trunkfield et al. Reference Trunkfield, Gurcha, Besra and Bugg2010).

The enzyme catalysing the translocation of Lipid II across the plasma membrane has been the subject of much debate. To date, there is evidence for two different enzymes with ‘flippase’ activity: MurJ and FtsW (Ruiz, Reference Ruiz2008, Reference Ruiz2015; Mohammadi et al. Reference Mohammadi, van Dam, Sijbrandi, Vernet, Zapun, Bouhss, Diepeveen-de Bruin, Nguyen-Disteche, de Kruijff and Breukink2011, Reference Mohammadi, Sijbrandi, Lutters, Verheul, Martin, den Blaauwen, de Kruijff and Breukink2014; Sham et al. Reference Sham, Butler, Lebar, Kahne, Bernhardt and Ruiz2014). Further biochemical characterization is required to confirm the identification of the ‘flippase’. Inhibitors against this enzyme would be expected to exhibit broad-spectrum activity, targeting a vital activity in all bacteria.

Following translocation across the plasma membrane, Lipid II is polymerized by the monofunctional and bifunctional Penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) (Sauvage et al. Reference Sauvage, Kerff, Terrak, Ayala and Charlier2008). Bifunctional PBPs (PonA1/PBP1 and PonA2/PBP2) possess transglycosylase and transpeptidase domains. The former domain is responsible for linking the disaccharide building blocks of Lipid II to the pre-existing glycan chains (with the concomitant release of decaprenyl pyrophosphate), whereas the latter domain catalyses the formation of the classical (3 → 4) cross-links, between m-DAP and D-Ala of the adjacent pentapeptide chains, with the cleavage of the terminal D-Ala. D,D-transpeptidation and D,D-carboxypeptidation is performed by the monofunctional PBPs, both resulting in the cleavage of the terminal D-Ala of the peptide stem (Goffin and Ghuysen, Reference Goffin and Ghuysen2002). Only 20% of the cross-links in Mtb peptidoglycan are (3 → 4) (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Arora, Lloyd, Lee, Nair, Fischer, Boshoff and Barry2012). The majority are (3 → 3) links between two tetrapeptide stems, with the release of the fourth position D-Ala (Lavollay et al. Reference Lavollay, Arthur, Fourgeaud, Dubost, Marie, Veziris, Blanot, Gutmann and Mainardi2008). This reaction is catalysed by the L,D-transpeptidases, with D,D-carboxypeptidation as a prerequisite activity. The L,D-transpeptidases are structurally unrelated to PBPs, with different active site residues (cysteine and serine, respectively) (Mainardi et al. Reference Mainardi, Fourgeaud, Hugonnet, Dubost, Brouard, Ouazzani, Rice, Gutmann and Arthur2005; Biarrotte-Sorin et al. Reference Biarrotte-Sorin, Hugonnet, Delfosse, Mainardi, Gutmann, Arthur and Mayer2006). The β-lactam antibiotics have been used in the treatment of bacterial infections for nearly a century, and gave rise to the discovery of their target, the PBPs. The L,D-transpeptidases are resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics, except the carbapenems (Dubee et al. Reference Dubee, Triboulet, Mainardi, Etheve-Quelquejeu, Gutmann, Marie, Dubost, Hugonnet and Arthur2012). Until recently, β-lactams were not considered for use in the treatment of TB, due to the expression of a broad-spectrum β-lactamase, BlaC. However, it has been shown that BlaC is irreversibly inactivated by clavulanic acid, yet hydrolyses carbapenems at a low rate (Hugonnet et al. Reference Hugonnet, Tremblay, Boshoff, Barry and Blanchard2009). Combined treatment of the β-lactam with the β-lactamase inhibitor has been shown to be bactericidal against both replicating and non-replicating forms of Mtb, and combinations are now being explored in clinical trials (Hugonnet et al. Reference Hugonnet, Tremblay, Boshoff, Barry and Blanchard2009; Rullas et al. Reference Rullas, Dhar, McKinney, Garcia-Perez, Lelievre, Diacon, Hugonnet, Arthur, Angulo-Barturen, Barros-Aguirre and Ballell2015). A well-documented inhibitor of the transglycosylase of PBPs, moenomycin (van Heijenoort et al. Reference van Heijenoort, Leduc, Singer and van Heijenoort1987), a natural product glycolipid, is yet to have proven efficacy against Mtb.

The inhibitors discussed thus far directly target the enzymes involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. There are, however, other antibiotics that act on the peptidoglycan precursors. For example, the glycopeptides, vancomycin and teicoplanin, bind to the D-Ala-D-Ala terminus of the pentapeptide stem, preventing polymerization reactions (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds1989). Members of the lantibiotic family of antibiotics, such as nisin, interact with the pyrophosphate moiety of Lipid II, forming a pore in the cytoplasmic membrane, but also inhibiting peptidoglycan biosynthesis (Wiedemann et al. Reference Wiedemann, Breukink, van Kraaij, Kuipers, Bierbaum, de Kruijff and Sahl2001). The lipoglycodepsipeptide ramoplanin inhibits the action of MurG by binding to Lipid I. Ramoplanin also binds to Lipid II, preventing its polymerization (Lo et al. Reference Lo, Men, Branstrom, Helm, Yao, Goldman and Walker2000).

ARABINOGALACTAN

The major cell wall polysaccharide, arabinogalactan (Fig. 1), as the name suggests, is composed of galactose and arabinose sugar residues, in the furanose (f) ring form (Galf) (McNeil et al. Reference McNeil, Wallner, Hunter and Brennan1987). Arabinogalactan is attached to peptidoglycan via a single linker unit (McNeil et al. Reference McNeil, Daffe and Brennan1990). The galactan component is a linear chain of approximately 30 alternating 5- and 6-linked β-D-Galf residues (Daffe et al. Reference Daffe, Brennan and McNeil1990). Three highly branched arabinan chains, consisting of approximately 30 Araf residues, are attached to the galactan chain (Besra et al. Reference Besra, Khoo, McNeil, Dell, Morris and Brennan1995). The non-reducing termini of the arabinan chains act as an attachment site for mycolic acids, succinyl and galactosamine (D-GalN) moieties (Draper et al. Reference Draper, Khoo, Chatterjee, Dell and Morris1997; Bhamidi et al. Reference Bhamidi, Scherman, Rithner, Prenni, Chatterjee, Khoo and McNeil2008).

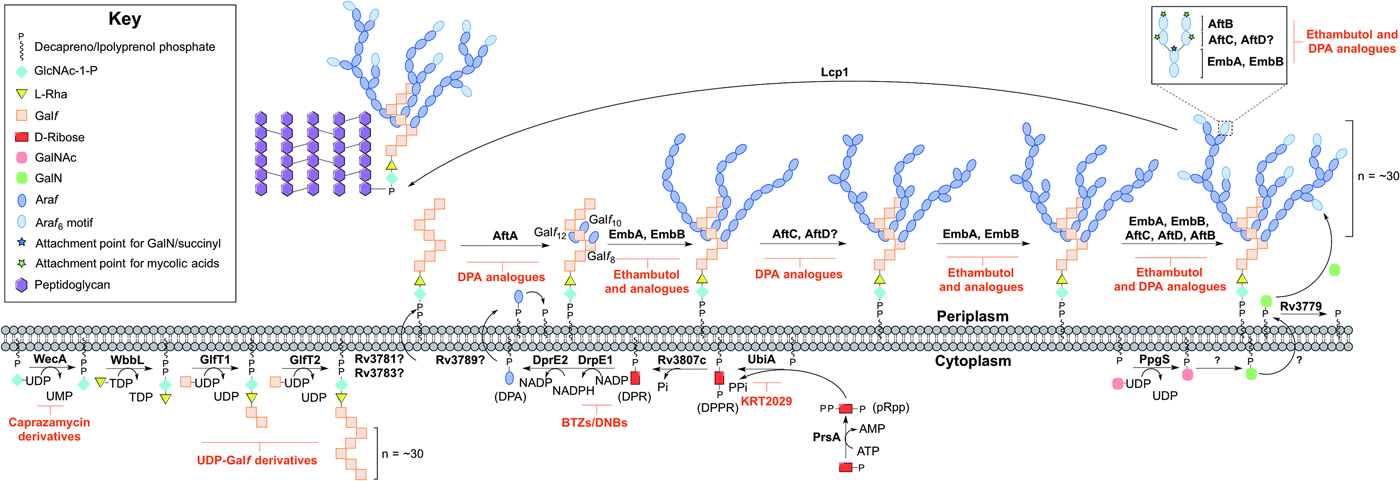

ARABINOGALACTAN BIOSYNTHESIS

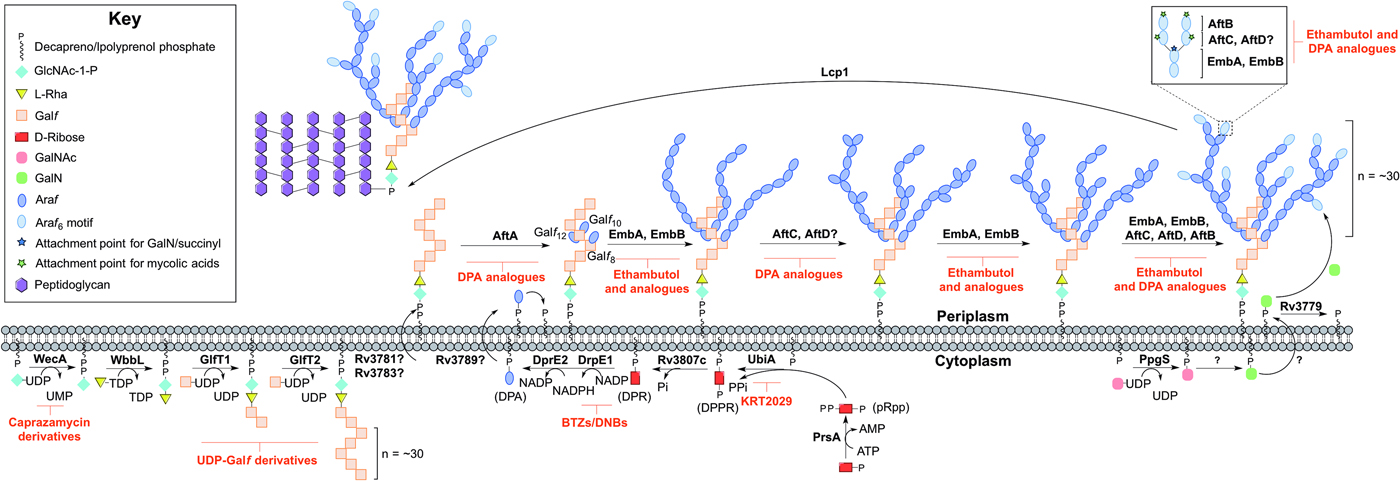

Arabinogalactan biosynthesis is illustrated in Fig. 3. The first committed step begins in the cytoplasm and proceeds by the formation of the linker unit connecting peptidoglycan to arabinogalactan, which is initiated by WecA, a GlcNAc-1-P transferase (Jin et al. Reference Jin, Xin, Zhang and Ma2010). This enzyme catalyses the transfer of GlcNAc-1-P to C50-P. WbbL, a rhamnosyltransferase catalyses the transfer of L-rhamnose (L-Rha) from dTDP-L-Rha to position 3 of C50-P-P-GlcNAc to form C50-P-P-GlcNAc-L-Rha, completing the linker unit (McNeil et al. Reference McNeil, Daffe and Brennan1990; Mills et al. Reference Mills, Motichka, Jucker, Wu, Uhlik, Stern, Scherman, Vissa, Pan, Kundu, Ma and McNeil2004). WecA has been identified as the target of caprazamycin derivatives, such as CPZEN-45, with the original nucleoside antibiotic shown to target MraY (Ishizaki et al. Reference Ishizaki, Hayashi, Inoue, Igarashi, Takahashi, Pujari, Crick, Brennan and Nomoto2013). Recently, a fluorescence-based assay for WecA activity has been developed and used to screen compound libraries with some success (Mitachi et al. Reference Mitachi, Siricilla, Yang, Kong, Skorupinska-Tudek, Swiezewska, Franzblau and Kurosu2016). Inhibitors targeting WbbL have yet to be identified. This essential enzyme, present in all mycobacteria, is recognized as a promising target and efforts are underway to characterize the enzyme via the establishment of a microtiter plate-based assay for its activity, which could be exploited in inhibitor library screening (Grzegorzewicz et al. Reference Grzegorzewicz, Ma, Jones, Crick, Liav and McNeil2008).

Fig. 3. Inhibitors targeting arabinogalactan biosynthesis. The current understanding of the roles of enzymes involved in arabinogalactan biosynthesis. Reported inhibitors are shown in red.

The linker unit provides an attachment point for the polymerization of the galactan chain. This process also occurs in the cytoplasm. The bifunctional galactofuranosyltransferases (GlfT1 and GlfT2) (Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Dover, Veerapen, Gurcha, Kremer, Roper, Pathak, Reynolds and Besra2008) are responsible for the synthesis of the linear galactan chain. Initially, GlfT1 transfers Galf from UDP-Galf to the C-4 position of L-Rha, and then adds a second Galf residue to the C-5 position of the primary Galf, generating C50-P-P-GlcNAc-L-Rha-Galf 2 (Mikusova et al. Reference Mikusova, Belanova, Kordulakova, Honda, McNeil, Mahapatra, Crick and Brennan2006; Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Dover, Veerapen, Gurcha, Kremer, Roper, Pathak, Reynolds and Besra2008; Belanova et al. Reference Belanova, Dianiskova, Brennan, Completo, Rose, Lowary and Mikusova2008). GlfT2 sequentially transfers Galf residues to the growing galactan chain with alternating β(1 → 5) and β(1 → 6) glycosidic linkages (Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Dover, Morehouse, Hitchin, Everett, Morris, Dell, Brennan, McNeil, Flaherty, Duncan and Besra2001a ; Rose et al. Reference Rose, Completo, Lin, McNeil, Palcic and Lowary2006). The galactan chains contain ~30 Galf residues in vivo, forming C50-P-P-GlcNAc-L-Rha-Galf 30 (Daffe et al. Reference Daffe, Brennan and McNeil1990), but the chain length determination mechanism is yet to be fully understood. GlfT1 and GlfT2 are suitable targets, as rationalized by an in silico target identification program (Raman et al. Reference Raman, Yeturu and Chandra2008). UDP-Galf derivatives, with modifications to the C-5 and C-6 positions have been investigated as suitable inhibitors of these enzymes, whereby they cause premature galactan chain termination (Peltier et al. Reference Peltier, Belanova, Dianiskova, Zhou, Zheng, Pearcey, Joe, Brennan, Nugier-Chauvin, Ferrieres, Lowary, Daniellou and Mikusova2010).

The remainder of arabinogalactan synthesis occurs on the outside of the cell. Although the transport mechanism of this cell wall polysaccharide is not fully understood, Rv3781 and Rv3783, encoding an ABC transporter, are potential ‘flippase’ candidates (Dianiskova et al. Reference Dianiskova, Kordulakova, Skovierova, Kaur, Jackson, Brennan and Mikusova2011). Araf residues are transferred directly onto C50-P-P-GlcNAc-L-Rha-Galf 30 from the lipid donor decaprenylphosphoryl-D-arabinose (DPA) (Wolucka et al. Reference Wolucka, McNeil, de Hoffmann, Chojnacki and Brennan1994). DPA is synthesized through a series of cytoplasmic steps, and originates exclusively from phospho-α-D-ribosyl-1-pyrophosphate (pRpp), prior to reorientation to the extracellular face of the plasma membrane. The pRpp synthetase, PrsA, catalyses the transfer of pyrophosphate from ATP to C-1 of ribose-5-phosphate, forming pRpp (Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Lloyd, Lloyd, Lovering, Eggeling and Besra2011b ). A decaprenyl moiety is added, catalysed by UbiA (decaprenol-1-phosphate 5-phosphoribosyltransferase), forming decaprenol-1-monophosphate 5-phosphoribose (Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Radmacher, Seidel, Gande, Hitchen, Morris, Dell, Sahm, Eggeling and Besra2005; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Scherman, D'Haeze, Vereecke, Holsters, Crick and McNeil2005, Reference Huang, Berg, Spencer, Vereecke, D'Haeze, Holsters and McNeil2008). Rv3807c encodes a putative phospholipid phosphatase, which catalyses C-5 dephosphorylation, generating decaprenol-1-phosphoribose (DPR) (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, He, Zhan, Zang, Ma, Zhao, Zhang and Xin2011). Finally, DPA is generated by an epimerization reaction of the ribose C-2 hydroxyl, catalysed by a two-step oxidation/reduction activity of the decaprenylphosphoribose-2′-epimerase consisting of subunits DprE1 and DprE2 (Mikusova et al. Reference Mikusova, Huang, Yagi, Holsters, Vereecke, D'Haeze, Scherman, Brennan, McNeil and Crick2005).

The DPA synthetic pathway is a validated drug target. The nitro-benzothiazinones (BTZs) and the structurally related dinitrobenzamides target DprE1 and are effective against MDR and XDR strains of Mtb with low toxicity (Christophe et al. Reference Christophe, Jackson, Jeon, Fenistein, Contreras-Dominguez, Kim, Genovesio, Carralot, Ewann, Kim, Lee, Kang, Seo, Park, Skovierova, Pham, Riccardi, Nam, Marsollier, Kempf, Joly-Guillou, Oh, Shin, No, Nehrbass, Brosch, Cole and Brodin2009; Batt et al. Reference Batt, Jabeen, Bhowruth, Quill, Lund, Eggeling, Alderwick, Futterer and Besra2012; Makarov et al. Reference Makarov, Lechartier, Zhang, Neres, van der Sar, Raadsen, Hartkoorn, Ryabova, Vocat, Decosterd, Widmer, Buclin, Bitter, Andries, Pojer, Dyson and Cole2014, Reference Makarov, Neres, Hartkoorn, Ryabova, Kazakova, Sarkan, Huszar, Piton, Kolly, Vocat, Conroy, Mikusova and Cole2015). The success of these compounds has led to the study of the other enzymes as potential drug targets. Conditional knockdown mutants of dprE1, dprE2, ubiA, prsA and Rv3807c have proven the essentiality of all except Rv3807c, and a target-based whole-cell screen has been developed using these strains of reduced expression levels to identify enzyme-specific inhibitors. Inhibitors targeting a particular enzyme cause increased sensitivity and this was confirmed with BTZ and KRT2029 targeting DprE1 and UbiA, respectively, and can be the subject of future medicinal chemistry efforts (Kolly et al. Reference Kolly, Boldrin, Sala, Dhar, Hartkoorn, Ventura, Serafini, McKinney, Manganelli and Cole2014).

The mechanism of DPA reorientation into the periplasm is unknown. The ‘flippase’ was recently considered to be Rv3789, but there is evidence that this protein plays a different role: to act as an anchor protein to recruit AftA (Kolly et al. Reference Kolly, Mukherjee, Kilacskova, Abriata, Raccaud, Blasko, Sala, Dal Peraro, Mikusova and Cole2015). AftA is the first arabinofuranosyltransferase (AraT), of a predicted six, to commence the addition of arabinose from DPA onto the galactan chain (Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Seidel, Sahm, Besra and Eggeling2006). AftA transfers a single Araf residue onto C-5 of β(1 → 6) Galf residues 8, 10 and 12 of C50-P-P-GlcNAc-L-Rha-Galf 30 (Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Radmacher, Seidel, Gande, Hitchen, Morris, Dell, Sahm, Eggeling and Besra2005). EmbA and EmbB, so called because their discovery was based on the mode of action elucidation of ethambutol (EMB), catalyse the addition of further α(1 → 5) Araf polymerization (Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Radmacher, Seidel, Gande, Hitchen, Morris, Dell, Sahm, Eggeling and Besra2005). AftC introduces α(1 → 3) branching (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Alderwick, Bhatt, Rittmann, Krumbach, Singh, Bai, Lowary, Eggeling and Besra2008), with AftD having an equivalent role (Skovierova et al. Reference Skovierova, Larrouy-Maumus, Zhang, Kaur, Barilone, Kordulakova, Gilleron, Guadagnini, Belanova, Prevost, Gicquel, Puzo, Chatterjee, Brennan, Nigou and Jackson2009). The structure terminates in a well-defined hexa-arabinofuranosyl (Araf 6) structural motif: [β-D-Araf-(1 → 2)-α-D-Araf]2-3,5-α-D-Araf-(1 → 5)-α-D-Araf. This motif is generated by EmbA, EmbB, AftC, AftD and AftB (Escuyer et al. Reference Escuyer, Lety, Torrelles, Khoo, Tang, Rithner, Frehel, McNeil, Brennan and Chatterjee2001; Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Radmacher, Seidel, Gande, Hitchen, Morris, Dell, Sahm, Eggeling and Besra2005; Birch et al. Reference Birch, Alderwick, Bhatt, Rittmann, Krumbach, Singh, Bai, Lowary, Eggeling and Besra2008, Reference Birch, Alderwick, Appelmelk, Maaskant, Bhatt, Singh, Nigou, Eggeling, Geurtsen and Besra2010; Skovierova et al. Reference Skovierova, Larrouy-Maumus, Zhang, Kaur, Barilone, Kordulakova, Gilleron, Guadagnini, Belanova, Prevost, Gicquel, Puzo, Chatterjee, Brennan, Nigou and Jackson2009). AftB catalyses the transfer of the terminal β(1 → 2) Araf residues (Seidel et al. Reference Seidel, Alderwick, Birch, Sahm, Eggeling and Besra2007). C-5 of the terminal β-D-Araf and the penultimate 2-α-D-Araf of this motif act as anchoring points for mycolic acids (McNeil et al. Reference McNeil, Daffe and Brennan1991).

The Emb arabinosyltransferases are inhibited by EMB, a well-recognized anti-TB drug, which is employed in the short-course treatment strategy of TB. Efforts are focused on investigating EMB analogues, such as SQ109 (Jia et al. Reference Jia, Coward, Gorman, Noker and Tomaszewski2005a , Reference Jia, Tomaszewski, Hanrahan, Coward, Noker, Gorman, Nikonenko and Protopopova b , Reference Jia, Tomaszewski, Noker, Gorman, Glaze and Protopopova c ; Sacksteder et al. Reference Sacksteder, Protopopova, Barry, Andries and Nacy2012) and SQ775 (Bogatcheva et al. Reference Bogatcheva, Hanrahan, Nikonenko, Samala, Chen, Gearhart, Barbosa, Einck, Nacy and Protopopova2006), for future lead drug development. Interestingly, the other AraTs are not inhibited by EMB (Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Seidel, Sahm, Besra and Eggeling2006; Seidel et al. Reference Seidel, Alderwick, Birch, Sahm, Eggeling and Besra2007; Birch et al. Reference Birch, Alderwick, Bhatt, Rittmann, Krumbach, Singh, Bai, Lowary, Eggeling and Besra2008) and screening for inhibitors against these enzymes is hindered due to the nature of the protein and substrate (membrane bound). However, there have been reports on the development of DPA analogues for the inhibition of arabinogalactan biosynthesis (Pathak et al. Reference Pathak, Pathak, Khare, Maddry and Reynolds2001; Owen et al. Reference Owen, Davis, Hartnell, Madge, Thomson, Chong, Coppel and von Itzstein2007). A recent study employing a cell free assay approach with membrane preparations has determined that various DPA analogues are able to limit the incorporation of a radiolabelled DP[14C]A (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Angala, Pramanik, Li, Crick, Liav, Jozwiak, Swiezewska, Jackson and Chatterjee2011).

The primary structure of arabinogalactan is completed by the transfer of succinyl and D-GalN residues to the inner arabinan units. PpgS, polyprenyl-phospho-N-acetylgalactosaminyl synthase, catalyses the formation of polyprenol-P-D-GalNAc from polyprenyl-P and UDP-GalNAc, which is then translocated across the membrane (Skovierova et al. Reference Skovierova, Larrouy-Maumus, Pham, Belanova, Barilone, Dasgupta, Mikusova, Gicquel, Gilleron, Brennan, Puzo, Nigou and Jackson2010; Rana et al. Reference Rana, Singh, Gurcha, Cox, Bhatt and Besra2012). The deacylation to polyprenol-P-D-GalN occurs in an undetermined location and by an unknown mechanism. The glycosyltransferase, Rv3779, transfers D-GalN to arabinogalactan at the C-2 position of 3,5-branched Araf residue (Scherman et al. Reference Scherman, Kaur, Pham, Skovierova, Jackson and Brennan2009; Skovierova et al. Reference Skovierova, Larrouy-Maumus, Pham, Belanova, Barilone, Dasgupta, Mikusova, Gicquel, Gilleron, Brennan, Puzo, Nigou and Jackson2010; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Zou, Bhamidi, McNeil and Lowary2012; Rana et al. Reference Rana, Singh, Gurcha, Cox, Bhatt and Besra2012). Succinylated Araf residues have also been detected at this position of non-mycolated arabinan chains (Bhamidi et al. Reference Bhamidi, Scherman, Rithner, Prenni, Chatterjee, Khoo and McNeil2008), but the enzyme responsible is currently unknown. A comprehensive mechanistic and functional understanding of these enzymes is required for evaluation as suitable drug targets and to date, there are no identified inhibitors against these processes. The final stage is the attachment of the arabinogalactan macromolecule to peptidoglycan. The enzyme responsible for this essential ligation has recently been elucidated to be Lcp1 (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Lloyd, Joe, Lowary, Reynolds, Walters-Morgan, Bhatt, Lovering, Besra and Alderwick2016).

PHOSPHATIDYL-MYO-INOSITOL MANNOSIDES, LIPOMANNAN AND LIPOARABINOMANNAN

The glycolipids, phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides (PIMs), and the related lipoglycans, lipomannan (LM) and lipoarabinomannan (LAM), are non-covalently anchored into the inner and outer membranes of the cell wall via the phosphatidyl-myo-inositol unit (Ortalo-Magne et al. Reference Ortalo-Magne, Lemassu, Laneelle, Bardou, Silve, Gounon, Marchal and Daffe1996) (Fig. 1). The core structure of PIM consists of an acylated sn-glycerol-3-phospho-(1-D-myo-inositol), the phosphatidyl inositol (PI) unit. Glycosylation with mannopyranose (Manp) residues at the O-2 and O-6 positions of myo-inositol, results in the mannosyl phosphate inositol (MPI) anchor (Ballou et al. Reference Ballou, Vilkas and Lederer1963; Ballou and Lee, Reference Ballou and Lee1964; Nigou et al. Reference Nigou, Gilleron, Brando and Puzo2004). The MPI structure is highly diverse, with variations in the type (commonly palmitic and tuberculostearic chains (Pitarque et al. Reference Pitarque, Herrmann, Duteyrat, Jackson, Stewart, Lecointe, Payre, Schwartz, Young, Marchal, Lagrange, Puzo, Gicquel, Nigou and Neyrolles2005)), number and location of acyl chains. The most prevalent forms of PIMs in mycobacteria are tri- and tetra-acylated phospho-myo-inositol di/hexamannosides (Ac1PIM2, Ac1PIM6, Ac2PIM2, Ac2PIM6), where in the hexamannosides, there is one Manp unit on the O-2 and five Manp units on the O-6 position of myo-inositol (Gilleron et al. Reference Gilleron, Ronet, Mempel, Monsarrat, Gachelin and Puzo2001). Extensions of mannan and arabinomannan chains on the MPI anchor form LM and LAM, respectively. In both LM and LAM, the mannan chain consists of approximately 21–34 α(1 → 6) linked Manp units, decorated with single α(1 → 2)-Manp residues (Kaur et al. Reference Kaur, Obregon-Henao, Pham, Chatterjee, Brennan and Jackson2008). In LAM, the mannan chain is glycosylated through an α(1 → 2) linkage with ~50–80 Araf residues (Khoo et al. Reference Khoo, Douglas, Azadi, Inamine, Besra, Mikusova, Brennan and Chatterjee1996).

In mycobacteria, PI and PIMs contribute up to 56% of all phospholipids in the cell wall and 37% in the cytoplasmic membrane (Goren, Reference Goren, Kubica and Wayne1984). These significant quantities indicate their importance. Not only are they structural components, they also have roles in cell wall integrity, permeability and control of septation and division (Parish et al. Reference Parish, Liu, Nikaido and Stoker1997; Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Waller, Jeevarajah, Billman-Jacobe and McConville2003; Fukuda et al. Reference Fukuda, Matsumura, Ato, Hamasaki, Nishiuchi, Murakami, Maeda, Yoshimori, Matsumoto, Kobayashi, Kinoshita and Morita2013). LM and LAM are involved in Mtb pathogenicity, with evidence to suggest they are modulators of host–pathogen interactions (Schlesinger et al. Reference Schlesinger, Hull and Kaufman1994; Nigou et al. Reference Nigou, Gilleron, Rojas, Garcia, Thurnher and Puzo2002; Maeda et al. Reference Maeda, Nigou, Herrmann, Jackson, Amara, Lagrange, Puzo, Gicquel and Neyrolles2003). These features of PIMs, LM and LAM make them suitable targets in anti-TB drug discovery.

BIOSYNTHESIS OF PHOSPHATIDYL-MYO-INOSITOL MANNOSIDES, LIPOMANNAN AND LIPOARABINOMANNAN

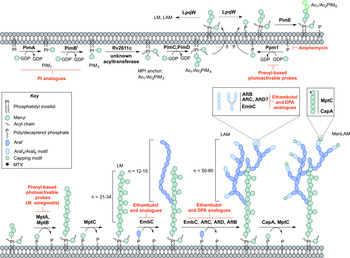

PIM biosynthesis begins in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4). The α-mannopyranosyl transferase (ManpT), PimA, of the GT-A/B superfamily, transfers Manp from the donor GDP-Manp to position O-2 of the myo-inositol ring to form PIM1 (Kordulakova et al. Reference Kordulakova, Gilleron, Mikusova, Puzo, Brennan, Gicquel and Jackson2002; Guerin et al. Reference Guerin, Kordulakova, Schaeffer, Svetlikova, Buschiazzo, Giganti, Gicquel, Mikusova, Jackson and Alzari2007). A second Manp residue is transferred to position O-6 of the myo-inositol ring by PimB’ to form PIM2 (Guerin et al. Reference Guerin, Kaur, Somashekar, Gibbs, Gest, Chatterjee, Brennan and Jackson2009). Acylation of the Manp residue of PIM1 is performed by the acyltransferase Rv2611c before or after the addition of the second Manp residue (Kordulakova et al. Reference Kordulakova, Gilleron, Puzo, Brennan, Gicquel, Mikusova and Jackson2003). The acylation of the C-3 position of the myo-inositol ring is performed by an unknown acyltransferase. This finishes the synthesis of the MPI anchor. Mannosylation of Ac1/Ac2PIM2 to Ac1/Ac2PIM3 is performed by a ManpT, designated PimC, but this enzyme is yet to be confirmed in Mtb H37Rv (Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Gurcha, Bifani, Hitchen, Baulard, Morris, Dell, Brennan and Besra2002b ). It is suspected that the subsequent addition of Manp to the non-reducing end of Ac1/Ac2PIM3 is performed by the unidentified PimC or PimD forming Ac1/Ac2PIM4. The ManpTs have been the subject of target-based screening programs. More specifically, in vitro PimA activity was screened with approximately 350 compounds. Several hit molecules exhibited significant inhibition, but the compounds did not exhibit in vivo activity in Mtb (Sipos et al. Reference Sipos, Pato, Szekely, Hartkoorn, Kekesi, Orfi, Szantai-Kis, Mikusova, Svetlikova, Kordulakova, Nagaraja, Godbole, Bush, Collin, Maxwell, Cole and Keri2015). Substrate analogues of PimA and PimB’, galactose-derived phosphonate analogs of PI, have also been developed, which show enzyme inhibition in a cell-free system (Dinev et al. Reference Dinev, Gannon, Egan, Watt, McConville and Williams2007).

Fig. 4. Inhibitors targeting the biosynthesis of phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides, lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan. The current understanding of the biosynthesis of PIMs, LM, LAM and ManLAM. Reported inhibitors are shown in red.

The biosynthesis of Ac1/Ac2PIM4 marks the transition towards the synthesis of higher order PIMs, LM and LAM (Fig. 4). It is predicted that the synthesis of Ac1/Ac2PIM4 occurs on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, and at this point, is flipped across the membrane by an unidentified translocase, with the remainder of the steps thought to occur in the periplasmic space. The integral membrane ManpTs (of the GT-C glycosyltransferase superfamily) are reliant on polyprenyl-phosphate-based mannose donors (PPM) rather than the nucleotide-based sugars (Berg et al. Reference Berg, Kaur, Jackson and Brennan2007). The polyprenol monophosphomannose synthase, Ppm1, catalyses the synthesis of PPM from GDP-Manp and polyprenol phosphates (Gurcha et al. Reference Gurcha, Baulard, Kremer, Locht, Moody, Muhlecker, Costello, Crick, Brennan and Besra2002).

PimE catalyses the transfer of an α(1 → 2)-linked Manp residue onto Ac1/Ac2PIM4, generating Ac1/Ac2PIM5 (Morita et al. Reference Morita, Sena, Waller, Kurokawa, Sernee, Nakatani, Haites, Billman-Jacobe, McConville, Maeda and Kinoshita2006). The transfer of the last Manp residue is either performed by PimE or by an unidentified GT-C glycosyltransferase forming Ac1/Ac2PIM6 (Morita et al. Reference Morita, Sena, Waller, Kurokawa, Sernee, Nakatani, Haites, Billman-Jacobe, McConville, Maeda and Kinoshita2006). The distal 2-linked Manp residues are not present in the mannan core of LM or LAM; Ac1/Ac2PIM4 is the likely precursor for the extension of the mannan chain. Recent evidence suggests that the putative lipoprotein LpqW channels intermediates such as Ac1/Ac2PIM4 towards either PimE (to form the polar lipids) or to LM and LAM synthesis (Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Kovacevic, Martin, Brammananth, Morita, Billman-Jacobe, McConville and Coppel2008). The mannosyltransferases, MptA and MptB (Mishra et al. Reference Mishra, Alderwick, Rittmann, Tatituri, Nigou, Gilleron, Eggeling and Besra2007, Reference Mishra, Alderwick, Rittmann, Wang, Bhatt, Jacobs, Takayama, Eggeling and Besra2008), are responsible for the α(1 → 6)-linked mannan core of LM and LAM. MptC catalyses the transfer of the monomannose side chains via α(1 → 2) linkages, forming mature LM (Kaur et al. Reference Kaur, Obregon-Henao, Pham, Chatterjee, Brennan and Jackson2008; Mishra et al. Reference Mishra, Krumbach, Rittmann, Appelmelk, Pathak, Pathak, Nigou, Geurtsen, Eggeling and Besra2011). Modification of LM leads to LAM. Approximately 50–80 Araf residues are added using DPA as the donor, comparable to that of the arabinogalactan domain. An unidentified ArafT primes the mannan chain, which is further elongated by EmbC, adding 12–16 Araf residues with α(1 → 5) linkages (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Berg, Lee, Spencer, Zhang, Vissa, McNeil, Khoo and Chatterjee2006; Alderwick et al. Reference Alderwick, Lloyd, Ghadbane, May, Bhatt, Eggeling, Futterer and Besra2011a ). AftC, the same enzyme involved in arabinogalactan synthesis, integrates α(1 → 3) Araf branches (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Alderwick, Bhatt, Rittmann, Krumbach, Singh, Bai, Lowary, Eggeling and Besra2008). It has also been speculated that AftD introduces α(1 → 3) Araf, but its function is yet to be confirmed (Skovierova et al. Reference Skovierova, Larrouy-Maumus, Zhang, Kaur, Barilone, Kordulakova, Gilleron, Guadagnini, Belanova, Prevost, Gicquel, Puzo, Chatterjee, Brennan, Nigou and Jackson2009). The arabinan domain is terminated by β(1 → 2) Araf linkages, predicted to be performed by AftB, resulting in branched hexa-arabinoside or linear tetra-arabinoside motifs. Further structural heterogeneity is introduced by capping motifs. These moieties consist of a number of α(1 → 2)-linked Manp residues, producing mannosylated LAM (ManLAM) (Kaur et al. Reference Kaur, Obregon-Henao, Pham, Chatterjee, Brennan and Jackson2008). Using PPM, the α(1 → 5) ManpT, CapA, attaches the first Manp residue (Dinadayala et al. Reference Dinadayala, Kaur, Berg, Amin, Vissa, Chatterjee, Brennan and Crick2006). MptC catalyses the addition of subsequent α(1 → 2) Manp residues (Kaur et al. Reference Kaur, Obregon-Henao, Pham, Chatterjee, Brennan and Jackson2008), which can be decorated with an α(1 → 4)-linked 5-deoxy-5-methyl-thio-xylofuranose (MTX) residue (Ludwiczak et al. Reference Ludwiczak, Gilleron, Bordat, Martin, Gicquel and Puzo2002; Turnbull et al. Reference Turnbull, Shimizu, Chatterjee, Homans and Treumann2004). The enzymes involved in the addition of MTX and succinyl residues to LAM are still to be determined.

The essentiality of PPM in lipoglycan biosynthesis makes Ppm1 an attractive drug target. Amphomycin, a lipopeptide antibiotic, inhibits the synthesis of PPM by sequestering the polyprenol phosphates, and consequently inhibits the extracellular ManpTs (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Scher and Waechter1981; Besra et al. Reference Besra, Morehouse, Rittner, Waechter and Brennan1997). Guy et al. (Reference Guy, Illarionov, Gurcha, Dover, Gibson, Smith, Minnikin and Besra2004) designed a variety of prenyl-based photoactivable probes. Upon photoactivation, a number of the probes exhibited inhibitory activity against Mtb Ppm1 and M. smegmatis α(1 → 6) ManpTs (Guy et al. Reference Guy, Illarionov, Gurcha, Dover, Gibson, Smith, Minnikin and Besra2004). Substrate analogues of the ManpTs have been designed to investigate enzyme–substrate interactions and mechanisms of action (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Field, Barker, Guy, Grewal, Khoo, Brennan, Besra and Chatterjec2001; Tam and Lowary, Reference Tam and Lowary2010). These types of studies will provide an invaluable insight into the interactions involved and for the future design of inhibitors.

MYCOLIC ACIDS

The final distinctive component of the mycobacterial cell wall is the unique fatty acids, termed the mycolic acids (Fig. 1). These unique long chain α-alkyl-β-hydroxy fatty acids (comprised a meromycolate chain of C42–C62 and a long saturated α-chain C24–C26) are attached to the arabinogalactan layer, but also make up other outer cell envelope lipids such as trehalose mono/di-mycolates and glucose monomycolate. There are three subclasses of mycolic acids: α-mycolates, containing cyclopropane rings in the cis-configuration; methoxy-mycolates and keto-mycolates containing methoxy or ketone groups, respectively, and have cyclopropane rings in the cis- or trans- configuration (Brennan and Nikaido, Reference Brennan and Nikaido1995; Watanabe et al. Reference Watanabe, Aoyagi, Ridell and Minnikin2001, Reference Watanabe, Aoyagi, Mitome, Fujita, Naoki, Ridell and Minnikin2002). Mycolic acids contribute to the permeability of the cell wall, and as such are essential for cell viability, and are also essential in virulence, making the biosynthesis of mycolates suitable drug targets (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Barry, Besra and Nikaido1996).

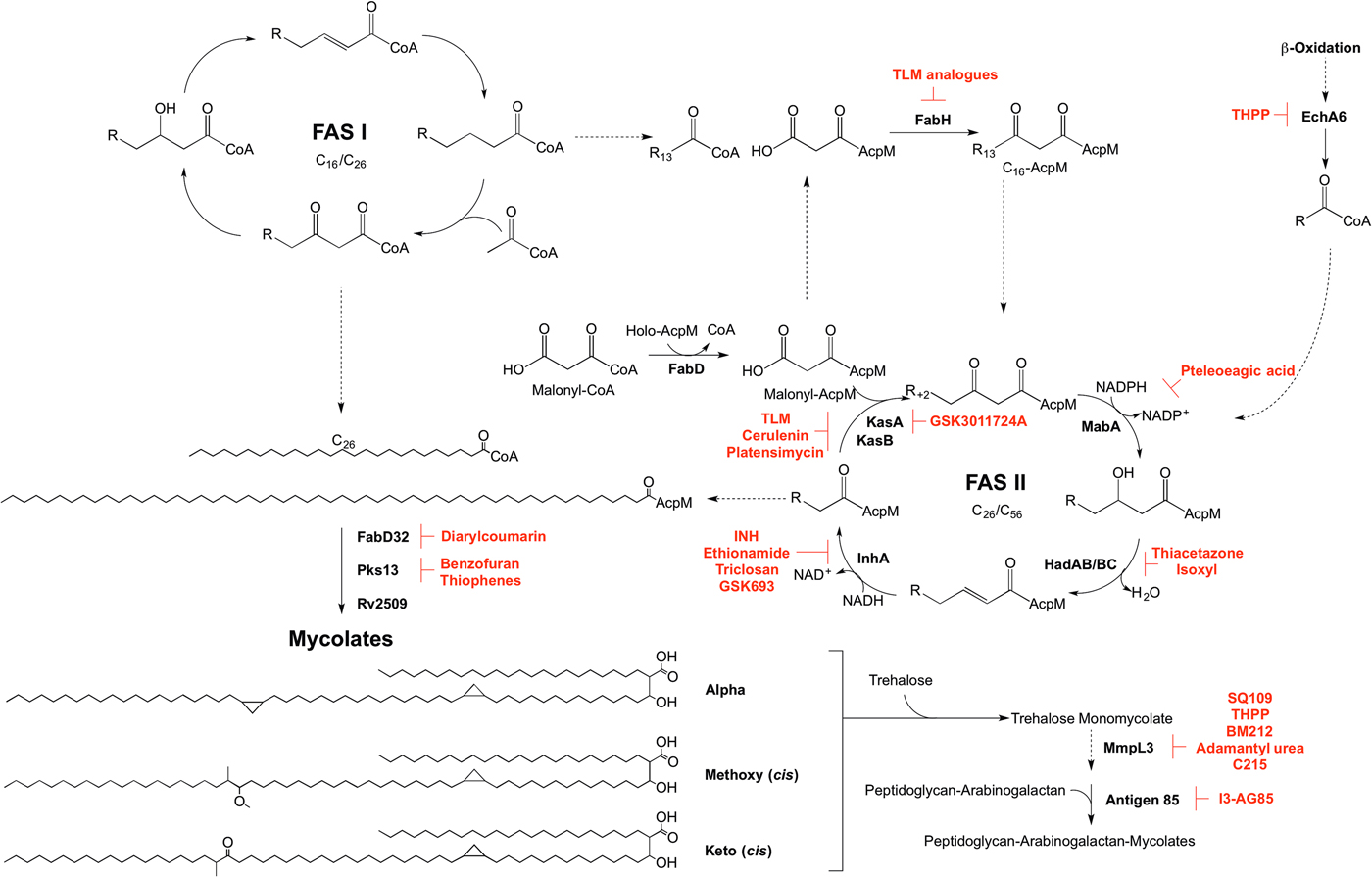

MYCOLIC ACID BIOSYNTHESIS

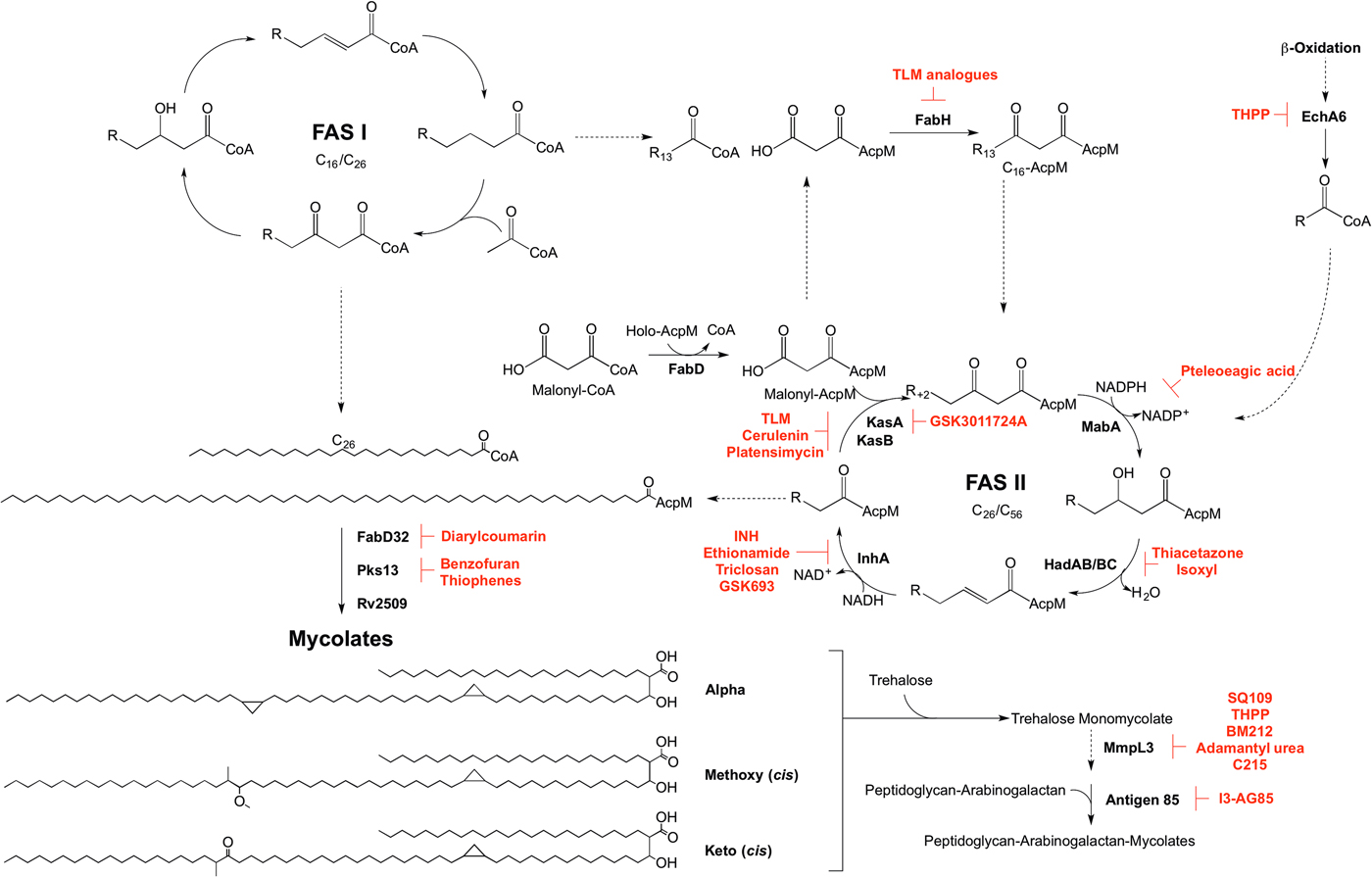

Mycolic acid biosynthesis occurs in the cytoplasm, involving two distinct pathways, termed fatty acid synthase types I and II (FAS I and FAS II) (Fig. 5). FAS I (Rv2524c), a multifunctional polypeptide, generates short-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters that can either form the saturated α-branch (C24), or be extended by FAS II to form the meromycolate chain (Cole et al. Reference Cole, Brosch, Parkhill, Garnier, Churcher, Harris, Gordon, Eiglmeier, Gas, Barry, Tekaia, Badcock, Basham, Brown, Chillingworth, Connor, Davies, Devlin, Feltwell, Gentles, Hamlin, Holroyd, Hornsby, Jagels, Krogh, McLean, Moule, Murphy, Oliver and Osborne1998). Elongation of the fatty acids is dependent on the availability of holo-AcpM, an acyl carrier protein, and malonyl-CoA. FabD, the malonyl:AcpM transacylase generates malonyl-AcpM (Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Nampoothiri, Lesjean, Dover, Graham, Betts, Brennan, Minnikin, Locht and Besra2001b ). C14-CoA primers from FAS I are condensed with malonyl-AcpM, catalysed by FabH (β-ketoacyl ACP synthase) (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Kremer, Besra and Rock2000), forming a pivotal link between the FAS I and FAS II pathways. The C16-AcpM formed is channeled to the FAS II pathway (Bhatt et al. Reference Bhatt, Molle, Besra, Jacobs and Kremer2007), where it undergoes a round of keto-reduction, dehydration and enoyl-reduction, catalysed by: MabA, a β-ketoacyl-AcpM reductase (Marrakchi et al. Reference Marrakchi, Ducasse, Labesse, Montrozier, Margeat, Emorine, Charpentier, Daffe and Quemard2002); HadAB/BC, a β-hydroxyacyl-AcpM hydratase (Sacco et al. Reference Sacco, Covarrubias, O'Hare, Carroll, Eynard, Jones, Parish, Daffe, Backbro and Quemard2007); InhA, an enoyl-AcpM reductase (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Dubnau, Quemard, Balasubramanian, Um, Wilson, Collins, de Lisle and Jacobs1994). Successive cycles ensue, whereby the condensation reaction of FabH is replaced by the activities of KasA and KasB, β-ketoacyl synthases (Schaeffer et al. Reference Schaeffer, Agnihotri, Volker, Kallender, Brennan and Lonsdale2001; Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Dover, Carrere, Nampoothiri, Lesjean, Brown, Brennan, Minnikin, Locht and Besra2002a ). The AcpM-bound acyl chain extends by two carbon units in each cycle, forming a saturated long-chain meromycolate of C42–C62, which is subject to modifications such as cis-/trans-cyclopropanation, and the addition of methoxy and keto groups (Dubnau et al. Reference Dubnau, Chan, Raynaud, Mohan, Laneelle, Yu, Quemard, Smith and Daffe2000; Glickman et al. Reference Glickman, Cox and Jacobs2000; Glickman, Reference Glickman2003; Barkan et al. Reference Barkan, Rao, Sukenick and Glickman2010). FabD32, a fatty acyl-AMP ligase, activates the meromycolate chain (Trivedi et al. Reference Trivedi, Arora, Sridharan, Tickoo, Mohanty and Gokhale2004) and the subsequent meromycolyl-AMP is linked with the α-alkyl-CoA ester, catalysed by Pks13, to generate a α-alkyl-β-keto-mycolic acid (Gande et al. Reference Gande, Gibson, Brown, Krumbach, Dover, Sahm, Shioyama, Oikawa, Besra and Eggeling2004; Portevin et al. Reference Portevin, De Sousa-D'Auria, Houssin, Grimaldi, Chami, Daffe and Guilhot2004). Finally a reduction step, catalysed by Rv2509, generates a mature mycolate (Bhatt et al. Reference Bhatt, Brown, Singh, Minnikin and Besra2008). Transport of the mycolates to either the cell envelope or for attachment to arabinogalactan remains to be elucidated. It is considered that the mycolates are transported in the form of trehalose monomycolate (TMM). In the generation of TMM, Takayama et al. (Reference Takayama, Wang and Besra2005) propose that a mycolyltransferase transfers the mycolyl group from mycolyl-Pks13 to D-mannopyranosyl-1-phosphoheptaprenol (Besra et al. Reference Besra, Sievert, Lee, Slayden, Brennan and Takayama1994). The mycolyl group of mycolyl-D-mannopyranosyl-1-phosphoheptaprenol is transferred to trehalose-6-phosphate by a second mycolyltransferase, forming TMM-phosphate. The phosphate moiety is removed by a trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase, and the TMM is immediately translocated outside of the cell using a resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family of efflux pumps, termed mycobacterial membrane proteins large (MmpL), limiting TMM accumulation in the cytoplasm (Takayama et al. Reference Takayama, Wang and Besra2005; Grzegorzewicz et al. Reference Grzegorzewicz, Pham, Gundi, Scherman, North, Hess, Jones, Gruppo, Born, Kordulakova, Chavadi, Morisseau, Lenaerts, Lee, McNeil and Jackson2012; Varela et al. Reference Varela, Rittmann, Singh, Krumbach, Bhatt, Eggeling, Besra and Bhatt2012). Finally, the mycolyltransferase Antigen 85 complex, formed of Ag85A, Ag85B and Ag85C, attaches the mycolic acid moiety from TMM to arabinogalactan (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Raynaud, Laneelle, Guilhot, Laurent-Winter, Ensergueix, Gicquel and Daffe1999). This complex also catalyses the formation of trehalose dimycolate, TDM, from two TMM molecules with the release of trehalose (Takayama et al. Reference Takayama, Wang and Besra2005). TDM, or ‘cord factor’, is implicated in the pathogenicity of Mtb.

Fig. 5. Inhibitors targeting mycolic acid biosynthesis. The enzymes involved in the mycolic acid biosynthetic pathway are presented. Reported inhibitors are shown in red. ‘R’ represents an acyl chain of varying carbon units in length.

The enzymes involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis are the targets of numerous inhibitors. In 1952, shortly after its discovery, isoniazid (INH) was administered as a front-line and essential antibiotic in the treatment of TB (Medical Research Council, 1952) and has only recently had the mode of action elucidated. Initially thought to target KatG due to mutations in the corresponding gene in resistant isolates (Zhang and Young, Reference Zhang and Young1994; Rouse and Morris, Reference Rouse and Morris1995), INH was later revealed to be a pro-drug, with the true target being InhA (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Dubnau, Quemard, Balasubramanian, Um, Wilson, Collins, de Lisle and Jacobs1994; Larsen et al. Reference Larsen, Vilcheze, Kremer, Besra, Parsons, Salfinger, Heifets, Hazbon, Alland, Sacchettini and Jacobs2002). Ethionamide, a structural analogue of INH, also requires cellular activation via EthA, before targeting InhA (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Dubnau, Quemard, Balasubramanian, Um, Wilson, Collins, de Lisle and Jacobs1994). Direct inhibitors of InhA that do not require activation are now being searched for (Lu et al. Reference Lu, You and Chen2010; Vilcheze et al. Reference Vilcheze, Baughn, Tufariello, Leung, Kuo, Basler, Alland, Sacchettini, Freundlich and Jacobs2011; Pan and Tonge, Reference Pan and Tonge2012; Encinas et al. Reference Encinas, O'Keefe, Neu, Remuinan, Patel, Guardia, Davie, Perez-Macias, Yang, Convery, Messer, Perez-Herran, Centrella, Alvarez-Gomez, Clark, Huss, O'Donovan, Ortega-Muro, McDowell, Castaneda, Arico-Muendel, Pajk, Rullas, Angulo-Barturen, Alvarez-Ruiz, Mendoza-Losana, Ballell Pages, Castro-Pichel and Evindar2014; Manjunatha et al. Reference Manjunatha, Rao, Kondreddi, Noble, Camacho, Tan, Ng, Ng, Ma, Lakshminarayana, Herve, Barnes, Yu, Kuhen, Blasco, Beer, Walker, Tonge, Glynne, Smith and Diagana2015; Sink et al. Reference Sink, Sosic, Zivec, Fernandez-Menendez, Turk, Pajk, Alvarez-Gomez, Lopez-Roman, Gonzales-Cortez, Rullas-Triconado, Angulo-Barturen, Barros, Ballell-Pages, Young, Encinas and Gobec2015; Martinez-Hoyos et al. Reference Martinez-Hoyos, Perez-Herran, Gulten, Encinas, Alvarez-Gomez, Alvarez, Ferrer-Bazaga, Garcia-Perez, Ortega, Angulo-Barturen, Rullas-Trincado, Blanco Ruano, Torres, Castaneda, Huss, Fernandez Menendez, Gonzalez Del Valle, Ballell, Barros, Modha, Dhar, Signorino-Gelo, McKinney, Garcia-Bustos, Lavandera, Sacchettini, Jimenez, Martin-Casabona, Castro-Pichel and Mendoza-Losana2016). One such molecule is the broad-spectrum antibiotic triclosan, which has not been adopted in TB treatment due to its sub-optimal bioavailability (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Falany and James2004). In the last year, GlaxoSmithKline have published a set of thiadiazole compounds, which directly target InhA, with GSK693 demonstrating in vivo efficacy comparable to INH (Martinez-Hoyos et al. Reference Martinez-Hoyos, Perez-Herran, Gulten, Encinas, Alvarez-Gomez, Alvarez, Ferrer-Bazaga, Garcia-Perez, Ortega, Angulo-Barturen, Rullas-Trincado, Blanco Ruano, Torres, Castaneda, Huss, Fernandez Menendez, Gonzalez Del Valle, Ballell, Barros, Modha, Dhar, Signorino-Gelo, McKinney, Garcia-Bustos, Lavandera, Sacchettini, Jimenez, Martin-Casabona, Castro-Pichel and Mendoza-Losana2016). Therefore, old drug targets should not be discounted in the search for new anti-tubercular agents.

The β-ketoacyl synthases, KasA and KasB, are the targets of the natural products cerulenin (Parrish et al. Reference Parrish, Kuhajda, Heine, Bishai and Dick1999; Schaeffer et al. Reference Schaeffer, Agnihotri, Volker, Kallender, Brennan and Lonsdale2001; Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Dover, Carrere, Nampoothiri, Lesjean, Brown, Brennan, Minnikin, Locht and Besra2002a ), platensimycin (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Taylor, Bhatt, Futterer and Besra2009), and thiolactomycin (TLM) (Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Douglas, Baulard, Morehouse, Guy, Alland, Dover, Lakey, Jacobs, Brennan, Minnikin and Besra2000; Schaeffer et al. Reference Schaeffer, Agnihotri, Volker, Kallender, Brennan and Lonsdale2001). There has been significant interest in TLM due to its broad-spectrum activity and numerous analogues have been synthesized to improve on potency and pharmacokinetic properties (Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Douglas, Baulard, Morehouse, Guy, Alland, Dover, Lakey, Jacobs, Brennan, Minnikin and Besra2000; Senior et al. Reference Senior, Illarionov, Gurcha, Campbell, Schaeffer, Minnikin and Besra2003, Reference Senior, Illarionov, Gurcha, Campbell, Schaeffer, Minnikin and Besra2004; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Zhang, Shenoy, Nguyen, Boshoff, Manjunatha, Goodwin, Lonsdale, Price, Miller, Duncan, White, Rock, Barry and Dowd2006). The biphenyl-based 5-substituents of TLM also exhibit in vitro activity against FabH, but with no whole-cell activity (Senior et al. Reference Senior, Illarionov, Gurcha, Campbell, Schaeffer, Minnikin and Besra2003, Reference Senior, Illarionov, Gurcha, Campbell, Schaeffer, Minnikin and Besra2004). The 2-tosylnaphthalene-1,4-diol pharmacophore of TLM also has in vitro activity against FabH, however, whole-cell data are yet to be published (Alhamadsheh et al. Reference Alhamadsheh, Waters, Sachdeva, Lee and Reynolds2008). Recently, a new anti-TB compound, an indazole sulfonamide GSK3011724A, was discovered from a phenotypic whole-cell HTS (Abrahams et al. Reference Abrahams, Chung, Ghidelli-Disse, Rullas, Rebollo-Lopez, Gurcha, Cox, Mendoza, Jimenez-Navarro, Martinez-Martinez, Neu, Shillings, Homes, Argyrou, Casanueva, Loman, Moynihan, Lelievre, Selenski, Axtman, Kremer, Bantscheff, Angulo-Barturen, Izquierdo, Cammack, Drewes, Ballell, Barros, Besra and Bates2016). The compound was shown to target KasA specifically, with no discernable target engagement with KasB or FabH, and is currently the focus of medicinal chemistry optimization (Abrahams et al. Reference Abrahams, Chung, Ghidelli-Disse, Rullas, Rebollo-Lopez, Gurcha, Cox, Mendoza, Jimenez-Navarro, Martinez-Martinez, Neu, Shillings, Homes, Argyrou, Casanueva, Loman, Moynihan, Lelievre, Selenski, Axtman, Kremer, Bantscheff, Angulo-Barturen, Izquierdo, Cammack, Drewes, Ballell, Barros, Besra and Bates2016).

Due to the success of InhA as a chemotherapeutic target, there is a mounting interest in the other enzymes involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis from a drug target perspective that could bypass INH resistance in MDR and XDR-TB. Formerly used in the treatment of TB, the thiocarbamide-containing drugs, thiacetazone and isoxyl, were shown to target mycolic acid biosynthesis and the inhibition mechanism has recently been elucidated. Following activation by EthA, both drugs target the HadA subunit of the HadABC dehydratase, forming a covalent interaction with the active site cysteine (Grzegorzewicz et al. Reference Grzegorzewicz, Eynard, Quemard, North, Margolis, Lindenberger, Jones, Kordulakova, Brennan, Lee, Ronning, McNeil and Jackson2015). It has also been shown that thiacetazone inhibits cyclopropanation of mycolic acids (Alahari et al. Reference Alahari, Trivelli, Guerardel, Dover, Besra, Sacchettini, Reynolds, Coxon and Kremer2007). MabA has been the subject of a molecular docking study. Comparable with the control inhibitory substrate isonicotinic-acyl-NADH, pteleoellagic acid had a high docking score with in vivo activity to be confirmed (Shilpi et al. Reference Shilpi, Ali, Saha, Hasan, Gray and Seidel2015). Through a target-based screening approach linked with whole-genome sequencing of resistant mutants, a benzofuran has been shown to target Pks13 (Ioerger et al. Reference Ioerger, O'Malley, Liao, Guinn, Hickey, Mohaideen, Murphy, Boshoff, Mizrahi, Rubin, Sassetti, Barry, Sherman, Parish and Sacchettini2013). Additionally, Pks13 is the target of thiophene compounds (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Kumar, Parashar, Vilcheze, Veyron-Churlet, Freundlich, Barnes, Walker, Szymonifka, Marchiano, Shenai, Colangeli, Jacobs, Neiditch, Kremer and Alland2013) including 2-aminothiophenes (Thanna et al. Reference Thanna, Knudson, Grzegorzewicz, Kapil, Goins, Ronning, Jackson, Slayden and Sucheck2016). From a GFP reporter-based whole-cell HTS, a diarylcoumarin exhibited potent activity against Mtb and this structural class was shown to target FadD32 by inhibiting the acyl–acyl carrier protein synthetase activity (Stanley et al. Reference Stanley, Kawate, Iwase, Shimizu, Clatworthy, Kazyanskaya, Sacchettini, Ioerger, Siddiqi, Minami, Aquadro, Grant, Rubin and Hung2013). The homologue of the Rv2509 reductase in M. smegmatis is non-essential but loss of function increases susceptibility to lipophilic antibiotics such as rifampicin. Targeting this ‘secondary’ drug target in Mtb could increase the susceptibility of the bacilli to antibiotics (Bhatt et al. Reference Bhatt, Brown, Singh, Minnikin and Besra2008). The Antigen 85 complex has been the focus of a number of inhibitor-based screening studies (Belisle et al. Reference Belisle, Vissa, Sievert, Takayama, Brennan and Besra1997; Gobec et al. Reference Gobec, Plantan, Mravljak, Wilson, Besra and Kikelj2004; Sanki et al. Reference Sanki, Boucau, Srivastava, Adams, Ronning and Sucheck2008, Reference Sanki, Boucau, Ronning and Sucheck2009; Elamin et al. Reference Elamin, Stehr, Oehlmann and Singh2009; Barry et al. Reference Barry, Backus, Barry and Davis2011). Recently, an inhibitor from a compound library was shown to bind to Antigen 85C, and derivatives of this compound have been synthesized, with 2-amino-6-propyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1-benzothiphene-3-carbonitrile (I3-AG85) exhibiting the lowest MIC in Mtb and drug-resistant strains (Warrier et al. Reference Warrier, Tropis, Werngren, Diehl, Gengenbacher, Schlegel, Schade, Oschkinat, Daffe, Hoffner, Eddine and Kaufmann2012).

In the target identification of new anti-tubercular compounds, some targets can be regarded as promiscuous, inhibited by multiple different chemical scaffolds, exemplified by MmpL3 (Grzegorzewicz et al. Reference Grzegorzewicz, Pham, Gundi, Scherman, North, Hess, Jones, Gruppo, Born, Kordulakova, Chavadi, Morisseau, Lenaerts, Lee, McNeil and Jackson2012; La Rosa et al. Reference La Rosa, Poce, Canseco, Buroni, Pasca, Biava, Raju, Porretta, Alfonso, Battilocchio, Javid, Sorrentino, Ioerger, Sacchettini, Manetti, Botta, De Logu, Rubin and De Rossi2012; Stanley et al. Reference Stanley, Grant, Kawate, Iwase, Shimizu, Wivagg, Silvis, Kazyanskaya, Aquadro, Golas, Fitzgerald, Dai, Zhang and Hung2012; Tahlan et al. Reference Tahlan, Wilson, Kastrinsky, Arora, Nair, Fischer, Barnes, Walker, Alland, Barry and Boshoff2012; Lun et al. Reference Lun, Guo, Onajole, Pieroni, Gunosewoyo, Chen, Tipparaju, Ammerman, Kozikowski and Bishai2013; Remuinan et al. Reference Remuinan, Perez-Herran, Rullas, Alemparte, Martinez-Hoyos, Dow, Afari, Mehta, Esquivias, Jimenez, Ortega-Muro, Fraile-Gabaldon, Spivey, Loman, Pallen, Constantinidou, Minick, Cacho, Rebollo-Lopez, Gonzalez, Sousa, Angulo-Barturen, Mendoza-Losana, Barros, Besra, Ballell and Cammack2013), a predicted TMM transporter. Through the generation and sequencing of spontaneous resistant mutants, a number of inhibitors with diverse chemical structures have been shown to target MmpL3 (Grzegorzewicz et al. Reference Grzegorzewicz, Pham, Gundi, Scherman, North, Hess, Jones, Gruppo, Born, Kordulakova, Chavadi, Morisseau, Lenaerts, Lee, McNeil and Jackson2012; La Rosa et al. Reference La Rosa, Poce, Canseco, Buroni, Pasca, Biava, Raju, Porretta, Alfonso, Battilocchio, Javid, Sorrentino, Ioerger, Sacchettini, Manetti, Botta, De Logu, Rubin and De Rossi2012; Stanley et al. Reference Stanley, Grant, Kawate, Iwase, Shimizu, Wivagg, Silvis, Kazyanskaya, Aquadro, Golas, Fitzgerald, Dai, Zhang and Hung2012; Tahlan et al. Reference Tahlan, Wilson, Kastrinsky, Arora, Nair, Fischer, Barnes, Walker, Alland, Barry and Boshoff2012; Lun et al. Reference Lun, Guo, Onajole, Pieroni, Gunosewoyo, Chen, Tipparaju, Ammerman, Kozikowski and Bishai2013; Remuinan et al. Reference Remuinan, Perez-Herran, Rullas, Alemparte, Martinez-Hoyos, Dow, Afari, Mehta, Esquivias, Jimenez, Ortega-Muro, Fraile-Gabaldon, Spivey, Loman, Pallen, Constantinidou, Minick, Cacho, Rebollo-Lopez, Gonzalez, Sousa, Angulo-Barturen, Mendoza-Losana, Barros, Besra, Ballell and Cammack2013). However, a recent chemoproteomics approach determined that one of the proposed inhibitor classes of MmpL3, the tetrahydropyrazo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamides (THPPs), has a novel alternative target, EchA6 (Cox et al. Reference Cox, Abrahams, Alemparte, Ghidelli-Disse, Rullas, Angulo-Barturen, Singh, Gurcha, Nataraj, Bethell, Remuiñán, Encinas, Jervis, Cammack, Bhatt, Kruse, Bantscheff, Futterer, Barros, Ballell, Drewes and Besra2016). Sequence analysis predicted EchA6 to be an enoyl-CoA hydratase, but it lacks the residues required for catalytic activity. Through an extensive biochemical investigation, Cox et al. (Reference Cox, Abrahams, Alemparte, Ghidelli-Disse, Rullas, Angulo-Barturen, Singh, Gurcha, Nataraj, Bethell, Remuiñán, Encinas, Jervis, Cammack, Bhatt, Kruse, Bantscheff, Futterer, Barros, Ballell, Drewes and Besra2016) predicted that EchA6 shuttles fatty acyl-CoA esters from the β-oxidation pathway into FAS II, ready for the condensation activities of KasA or KasB with malonyl-AcpM. This research demonstrates that target identification of inhibitory compounds can unveil not only a new biological pathway, but also an untapped area for drug targets.

DRUG DISCOVERY EFFORTS

The strategies involved in drug discovery are forever evolving. Traditional enzyme screening campaigns and medicinal chemistry focused on ligand-based inhibitor designs (such as substrate or transition state analogues) that once dominated drug discovery are being superseded by phenotypic HTS. The former approach often relies on the X-ray crystal structure of the enzyme or biochemical understanding, and successful inhibitors from these screens are further challenged by target engagement in vivo. Over recent years, HTS has become the lead approach in drug discovery. HTS employs extensive compound libraries of diverse chemical structures, and as a consequence, these methods can identify a multitude of inhibitors with novel chemical scaffolds. Phenotypic HTS can reveal anti-TB agents with whole-cell activity and unknown modes of action, having the potential to unveil new biochemical pathways (Abrahams et al. Reference Abrahams, Cox, Spivey, Loman, Pallen, Constantinidou, Fernandez, Alemparte, Remuinan, Barros, Ballell and Besra2012, Reference Abrahams, Chung, Ghidelli-Disse, Rullas, Rebollo-Lopez, Gurcha, Cox, Mendoza, Jimenez-Navarro, Martinez-Martinez, Neu, Shillings, Homes, Argyrou, Casanueva, Loman, Moynihan, Lelievre, Selenski, Axtman, Kremer, Bantscheff, Angulo-Barturen, Izquierdo, Cammack, Drewes, Ballell, Barros, Besra and Bates2016; Gurcha et al. Reference Gurcha, Usha, Cox, Futterer, Abrahams, Bhatt, Alderwick, Reynolds, Loman, Nataraj, Alemparte, Barros, Lloyd, Ballell, Hobrath and Besra2014; Mugumbate et al. Reference Mugumbate, Abrahams, Cox, Papadatos, van Westen, Lelievre, Calus, Loman, Ballell, Barros, Overington and Besra2015). Alternatively, phenotypic HTS can be target-based, focusing on enzymes or pathways such as those involved in cell wall biosynthesis. This can be a very effective way to identify novel anti-TB compounds with known modes of action, but is limited by the specified target (Batt et al. Reference Batt, Izquierdo, Pichel, Stubbs, Del Peral, Perez-Herran, Dhar, Mouzon, Rees, Hutchinson, Young, McKinney, Barros-Aguirre, Ballell Pages, Besra and Argyrou2015; Martinez-Hoyos et al. Reference Martinez-Hoyos, Perez-Herran, Gulten, Encinas, Alvarez-Gomez, Alvarez, Ferrer-Bazaga, Garcia-Perez, Ortega, Angulo-Barturen, Rullas-Trincado, Blanco Ruano, Torres, Castaneda, Huss, Fernandez Menendez, Gonzalez Del Valle, Ballell, Barros, Modha, Dhar, Signorino-Gelo, McKinney, Garcia-Bustos, Lavandera, Sacchettini, Jimenez, Martin-Casabona, Castro-Pichel and Mendoza-Losana2016). Target assignment is a fundamental step in in the drug discovery pipeline. Without knowledge of the physiological target, efforts can be wasted on developing compounds against an unsuitable target, such as those homologous in humans. Establishing the mode of action of an inhibitor is a prerequisite for facilitating medicinal chemistry efforts to convert compounds into potential drug candidates.

Concluding remarks

The essential mycobacterial cell wall, responsible for structural integrity, permeability and pathogenicity, is an attractive drug target, both structurally and biosynthetically. Recent advancements in biochemical and omics-based techniques have led to the discovery and mechanistic understanding of enzymes involved in mycobacterial cell wall synthesis and assembly. Although a number of key enzymes are yet to be established, there are a plethora of suitable targets, exploited not only in current treatment programmes but also for anti-TB drug discovery. In the current TB treatment regimen, two of the front-line drugs, INH and EMB, target mycolic acid and arabinogalactan biosynthesis, respectively, with the second-line drugs such as ethionamide and D-cycloserine also targeting cell wall production. The proven success of these drugs validates the future development of inhibitors targeting the unique mycobacterial cell wall, which remains a source of unexploited clinically relevant drug targets. The continued progression in drug discovery approaches and the optimization of biochemical techniques, will enable the rapid identification of anti-TB agents, many of which are likely to target the biosynthesis of the so-called ‘Achilles heel’ of Mtb.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jonathan Cox for his technical support and advice.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

G.S.B. acknowledges support in the form of a Personal Research Chair from Mr James Bardrick, a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award, the Medical Research Council (MR/K012118/1) and the Wellcome Trust (081569/Z/06/Z).