Introduction

Quill mites of the family Syringophilidae (Prostigmata: Cheyletoidea) are specialized parasites of birds. These parasites occupy a distinct ecological niche, i.e., the interior cavities of feather quills, where they spend most of their life, feed and reproduce (Kethley, Reference Kethley1970, Reference Kethley1971; Skoracki, Reference Skoracki2011). Among quill-dwelling mites (e.g., Apionacaridae, Ascouracaridae, Syringobiidae), this family is the most diverse taxonomic group and can be found in various microhabitats of their hosts, i.e., feathers of different types: primaries, secondaries, wing and tail coverts, and body contour feathers. Currently, approximately 400 described species of syringophilid mites in 2 subfamilies, parasitize birds from 27 out of the 44 extant avian orders (Skoracki et al., Reference Skoracki, Fajfer, Hromada, Hušek and Sikora2023; Zmudzinski et al., Reference Zmudzinski, Skoracki and Sikora2023).

Parrots (Psittaciformes) are remarkable for harbouring a highly diverse array of quill mites both in their taxonomy and morphology. Over the course of the past half-century, 45 species grouped into 8 genera and 2 subfamilies have been recorded on parrots belonging to all extant families, Cacatuidae, Psittacidae, Psittaculidae and Strigopidae (Fain et al., Reference Fain, Bochkov and Mironov2000; Bochkov and Perez, Reference Bochkov and Perez2002; Bochkov and Fain, Reference Bochkov and Fain2003; Skoracki, Reference Skoracki2005; Skoracki and Sikora, Reference Skoracki and Sikora2008; Glowska and Laniecka, Reference Glowska and Laniecka2013; Skoracki and Hromada, Reference Skoracki and Hromada2013; Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019a, Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019b; Marciniak-Musial and Sikora, Reference Marciniak-Musial and Sikora2022; Marciniak-Musial et al., Reference Marciniak-Musial, Hromada and Sikora2022, Reference Marciniak-Musial, Skoracki, Kosicki, Unsöld and Sikora2023). The Carolina parakeet, Conuropsis carolinensis Linnaeus, 1758 (Psittacidae) was examined as part of an ongoing project focusing on the collection of parasitic mites from birds deposited in the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology (Munich, Germany).

The Carolina parakeet was the only indigenous parrot species in the United States, with 2 subspecies, C. c. carolinensis (Linnaeus) distributed from Virginia to Florida, and C. c. ludoviciana (Gmelin) distributed across the Mississippi–Missouri River drainages (Clements et al., Reference Clements, Rasmussen, Schulenberg, Iliff, Fredericks, Gerbracht, Lepage, Spencer, Billerman, Sullivan and Wood2023). These colourful birds measured 30 cm in length and lived in dense flocks in the woods, primarily near rivers or swamps, where fed on seeds and fruits (Hume, Reference Hume2017; Snyder and Russell, Reference Snyder, Russell, Poole and Gill2020). This species was regarded as an agricultural pest because flocks significantly damaged farmland. Furthermore, ‘sportsmen’ slaughtered them in large numbers for amusement; it was quite easy to kill an entire flock as the parakeets would continually return to check on their deceased flock mates, that made these birds easy targets. Additionally, hundreds were captured alive annually for the pet trade and zoological gardens. The last confirmed sighting in the wild was a flock of 13 specimens in Florida in April 1904 (Hume, Reference Hume2017). In 1917, ‘Lady Jane’, the female of the last captive pair at the Cincinnati Zoo, died, leaving her male counterpart ‘Incas’ as the last surviving member of the species. Incas died in the following year, and his body was frozen in a block of ice for shipment to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, similar to ‘Martha’, the last Passenger Pigeon Ectopistes migratorius, who had died 4 years earlier at the same zoo. Unlike Martha, however, the Incas's body has never reached its intended destination (Fuller, Reference Fuller2014).

Regrettably, the Carolina parakeet eluded thorough biological research prior to its disappearance. Consequently, numerous details about its ecological niche and the exact reasons for its extinction are likely to remain uncertain or a matter of conjecture (Snyder and Russell, Reference Snyder, Russell, Poole and Gill2020). Currently, more than 700 skins of the Carolina parakeet are preserved in collections worldwide, serving as valuable resources for parasitological research. It is worth noting that among mites permanently associated with birds, 6 new feather mite species belonging to the 3 families (Astigmata: Pterolichidae, Psoroptoididae and Xolalgidae) have been reported from the Carolina parakeet (Mironov et al., Reference Mironov, Dabert and Ehrnsberger2005), whereas prostigmatan mites have never been recorded from this host.

Materials and methods

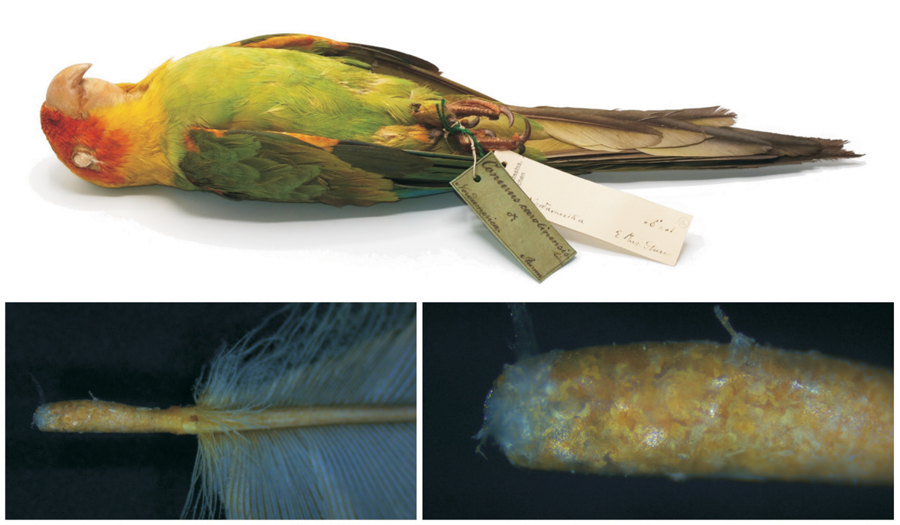

Mites were collected from the lesser wing covert of the single museum skin of the Carolina parakeet housed at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Munich, Germany (Fig. 1). An infested feather was carefully opened using a stereomicroscope and 2 sharp-tipped tweezers. For light microscopy, mites were initially softened in Nesbitt's solution at 40°C for approximately 48 hours and then mounted on slides in Faure's medium (Walter and Krantz, Reference Walter, Krantz, Krantz and Walter2009).

Figure 1. Specimen of the Carolina parakeet housed in the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Munich, Germany, and the infested feather quill.

Identification of the mite specimens and the preparation of drawings were carried out using a ZEISS Axioscope 2 (Carl-Zeiss AG, Germany) light microscope equipped with Difference-Interference-Contrast (DIC) optics and a camera lucida. All measurements are given in micrometres, with the range for paratypes provided in parentheses following the data for the holotype. The nomenclature for idiosomal chaetotaxy follows that of Grandjean (Reference Grandjean1939), as adapted for Prostigmata by Kethley (Reference Kethley and Dindal1990). The leg setation follows Grandjean (Reference Grandjean1944), and general morphological terms follow Skoracki (Reference Skoracki2011).

Specimen depositories and reference numbers are cited using the following abbreviations AMU – Adam Mickiewicz University, Department of Animal Morphology, Poznan, Poland; SNSB-ZSM – Bavarian State Collection for Zoology, Section Arthropoda Varia, Munich, Germany.

Results

Family Syringophilidae Lavoipierre, 1953

Subfamily Syringophilinae Lavoipierre, 1953

Genus Peristerophila Kethley, Reference Kethley1970

Peristerophila conuropsis sp. n.

(Fig. 2)

Figure 2. Peristerophila conuropsis sp. n., female. (A) dorsal view; (B) ventral view; (C) gnathosoma in ventral view; (D) peritreme; (E) solenidia of leg I. Scale bars – A, B = 100 μm; C–E = 25 μm.

Female, holotype. Total body length 810 (760–865 in 12 paratypes). Body view as in Figs 2A, B. Gnathosoma. Hypostomal apex with 2 pairs of large finger-like protuberances (Fig. 2C). Infracapitulum sparsely punctate. Each medial branch of peritremes with 3 chambers, each lateral branch with 4 chambers (Fig. 2D). Stylophore 195 (180–195) long; exposed portion of stylophore apunctate, 150 (145–150) long. Movable cheliceral digit 145 (145–150) long. Idiosoma. Propodonotal shield, entire, bearing bases of setae ve and si, covered with minute punctations. Bases of setae c1 situated posterior to level of setal bases se; c2 situated anterior to level of se or both pair of setae situated at same transverse level. Setae ve and si short (shorter than 30); length ratio of setae ve:si 1:1.3–1.7. Setae se, c1 and c2 long (longer than 200) and subequal in length. Hysteronotal shield reduced to small sclerite situated between setal bases d1–d1 and e2–e2. Bases of setae d1 situated equidistant between setal bases d2 and e2. Setae d1, d2 and e2 subequal in length. Pygidial shield with rounded anterior margin, sparsely punctate near bases of setae f1 and f2. Length ratio of setae f1:h1:f2:h2 1:1:7–9:12–13; ag1:ag2:ag3 3–5.2:1:4.5–6.2. Genital plate absent. Genital and pseudanal setae subequal in length or setae g2 and ps2 1.3–1.5 times longer than g1 and ps1. Coxal fields I sparsely punctate, II–IV apunctate; coxal fields III in close proximity to each other, with anterior margin not reaching bases of setae 3a. Setae 3c 2.7–4.2 times longer than 3b. Cuticular striations as in Fig. 2A, B. Legs. Fan-like setae p′ and p″ of legs I with 5–7, II with 6–8, III and IV with 10–11 tines. Solenidia of legs I as in Fig. 2E. Femora I punctate ventrally, other podomers apunctate. Lengths of setae: ve 20 (15–20), si 30 (25–30), se 240 (220–240), c1 245 (225–245), c2 220 (200–225), d1 230 (210–225), d2 205 (200–205), e2 195 (185–195), f1 25 (25–35), f2 225 (220–225), h1 25 (25–30), h2 310 (305–320), g1 20 (15–20), g2 20 (20–30), ps1 20 (15–20), ps2 25 (20–30), ag1 120 (100–130), ag2 25 (25–35), ag3 155 (130–150), tc′III–IV 15 (15), tc″III–IV 60 (55–60), 3b and 4b 30 (25–35), 3c and 4c 110 (95–110), l′RI (15–25), l′RII (25–30), l′RIII 30 (30–40), l′RIV 25 (25–30).

Male. Not found.

Type material. Female holotype and paratypes: 12 females, 3 tritonymphs and 3 protonymphs from the quill of small wing covert of the Carolina parakeet C. carolinensis Linnaeus, 1758 (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae); North America, no other data.

Type material deposition. Holotype and paratypes are deposited in the SNSB-ZSM (reg. no. SNSB-ZSM A20112209), except for 5 female paratypes in the AMU (reg. no. MS 23-0621-001).

Differential diagnosis. Peristerophila conuropsis sp. n. is morphologically most similar to the P. nestoriae Marciniak et al. Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019a, Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019b, described from the New Zealand Kaka, Nestor meridionalis (Gmelin) (Psittaciformes: Strigopidae), in New Zealand (Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019b). In females of both species, the propodonotal shield is entire, and the hysteronotal shield is reduced to the small sclerite situated between setal bases d1–d1 and e2–e2. This species differs from P. nestoriae by the following features: in females of P. conuropsis, the length of the stylophore is 180–195; bases of setae c1 are situated posterior to the level of setal bases se; the hysteronotal setae d2 and e2 are subequal in length; the anterior margin of coxal fields III not reaching bases of setae 3a, and the lengths of setae e2 and f2 are 185–195 and 220–225, respectively. In females of P. nestoriae, the length of the stylophore is 130–140; bases of setae c1 and se are situated in the same transverse level; the hysteronotal setae d2 are 1.2–1.5 times longer than e2; the anterior margin of coxal fields III reaching bases of setae 3a, and the lengths of setae e2 and f2 are 116–146 and 140–155, respectively.

Etymology. The specific name ‘conuropsis’ is taken from the generic name of the host and is a noun in apposition.

Discussion

Exploration of parasites from extinct bird species yields distinctive insights into the ecology and evolution of the hosts and their parasitic associates. Parasites often exhibit intimate associations with the biology, ecology and evolution of their hosts, rendering them a vital source of information regarding extinct species. They can provide insights into the diet, behaviour and living environment of extinct bird species. Moreover, studies on parasites and their extinct hosts can yield data regarding reciprocal adaptations and coevolutionary processes. And finally, unveiling new parasite species from extinct bird species can provide insights into the biodiversity and ecology of parasites in the past.

Until now, the order Psittaciformes has a distinctive quill mite fauna consisting of 45 species spread across 8 genera. Currently, mites from the Syringophilidae family have been identified from 82 parrot species of all extant families, Cacatuidae, Psittacidae, Psittaculidae and Strigopidae (Marciniak-Musial et al., Reference Marciniak-Musial, Skoracki, Kosicki, Unsöld and Sikora2023). As for the whole family Syringophilidae, most syringophilid species associated with parrots are restricted to a single host species (monoxenous parasites; 63% of the total quill mite fauna associated with parrots). Mite species that are associated with phylogenetically closely related host species within the same genus (stenoxenous parasites; 18%) or family (oligoxenous parasites; 17%) constitute a minority. A negligible portion of the syringophilid fauna related to parrots includes species that infest more or less unrelated host species, being polyxenous parasites (2%) (Marciniak-Musial et al., Reference Marciniak-Musial, Skoracki, Kosicki, Unsöld and Sikora2023).

One of the genera associated with parrots is the genus Peristerophila, to which the newly described species belongs. This genus boasts the broadest host spectrum among all known syringophilid genera. It includes 14 species and uniquely inhabits not only parrots but also hawks (Accipitriformes), falcons (Falconiformes), pigeons and doves (Columbiformes), hoopoes (Bucerotiformes) and bee-eaters (Coraciiformes) (Casto, Reference Casto1976; Skoracki et al., Reference Skoracki, Lontkowski and Stawarczyk2010, Reference Skoracki, Hromada and Sikora2017, Reference Skoracki, Hromada, Kaszewska and Sikora2020, Reference Skoracki, Kosicki, Sikora, Töpfer, Hušek, Unsöld and Hromada2021; Kaszewska et al., Reference Kaszewska, Skoracki, Kosicki and Hromada2020). The Peristerophila fauna associated with parrots includes 3 species noted on representatives of the parrot families Psittaculidae, Psittacidae and Strigopidae. Of these 3 mite species, 2 are monoxenous and exclusively related to parrots Peristerophila nestoriae Marciniak et al. Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019a, Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019b, is associated with the New Zealand Kaka Nestor meridionalis (Gmelin) (Strigopidae) in New Zealand, and Peristerophila forpi (Bochkov and Perez, Reference Bochkov and Perez2002) lives on with the Mexican Parrotlet Forpus cyanopygius (Souancé) (Psittacidae) in Mexico (Bochkov and Perez, Reference Bochkov and Perez2002; Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Skoracki and Hromada2019b). The third species, Peristerophila mucuya Casto, 1980, is currently regarded as a polyxenous parasite inhabiting several hosts from the orders Psittaciformes, i.e., the white-winged parakeet Brotogeris versicolurus (St. Muller) (Psittacidae) from Brazil; the gray-hooded parakeet Psilopsiagon aymara (d'Orbigny) (Psittacidae) from South America, and the coconut lorikeet Trichoglossus haematodus (Linnaeus) (Psittaculidae) from Indonesia, and also occurring on pigeons and doves (Columbiformes: Columbidae) (Bochkov and Fain, Reference Bochkov and Fain2003; Kaszewska-Gilas, et al., Reference Kaszewska-Gilas, Kosicki, Hromada and Skoracki2021; Marciniak-Musial and Sikora, Reference Marciniak-Musial and Sikora2022), although, it is possible that this species represents a series of cryptic species which are more host-specific.

Taking into account that the mite family Syringophilidae largely comprises highly host-specific species, in most cases represented by monoxenous parasites (Skoracki, Reference Skoracki2011; Skoracki et al., Reference Skoracki, Sikora and Spicer2016), it is highly probable that the extinction of the Carolina parakeet also led to the extinction of this particular parasite species, P. conuropsis. It might also be suggested that this species is an oligoxenous parasite restricted to birds closely related to each other, e.g., belonging to 1 genus. However, an issue arises here because the genus Conuropsis, established by Linnaeus, is monotypic. An attempt could be made to find this species on its closest living relatives. The majority of researchers have proposed that Conuropsis is most closely related to the genus Aratinga, a deduction derived from shared morphological characteristics (Forshaw, Reference Forshaw1989; Snyder, Reference Snyder2004). Mitochondrial DNA extracted from museum specimens of the Carolina parakeet strongly supported a sister relationship with a clade that includes Aratinga nenday (Vieillot), A. solstitialis (Linnaeus) and A. auricapillus (Kuhl) (Kirchman et al., Reference Kirchman, Schirtzinger and Wright2012). However, according to Skoracki (Reference Skoracki2011), 2 different syringophilid species do not co-occupy the same habitat type in the plumage; thus, the presence of Peristerophila on hosts from the genus Aratinga is unlikely. This is because these birds host a different quill mite species from the genus Neoaulobia Fain et al., Reference Fain, Bochkov and Mironov2000, which occupies the same habitat type (wing coverts) being also typical for Peristerophila. Therefore, with a high degree of probability, it should be accepted that the parasite species P. conuropsis has become extinct along with its host.

Data availability statement

All the data analysed in the current paper can be made available on request to MS.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all members of the Society – Freunde der Zoologischen Staatssammlung München e. V. – for their invaluable support during our research tenure at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Munich, Germany. We also thank reviewers for their constructive comments and valuable advice.

Author's contribution

Conceptualization – M. S. and M. U., methodology and investigation – M. S, M. P. and B. S., material collection – M. S., writing and original draft preparation – all authors, visualization – M. S. and M. U.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.