Article contents

Coccidial oocyst release: once a day or all day long? Tropical bird hosts shed new light on the adaptive significance of diurnal periodicity in parasite output

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2021

Abstract

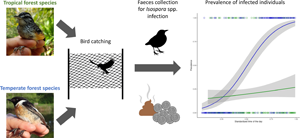

Many parasites spend part of their life cycle as infectious forms released from an infected host in the external environment, where they may encounter and infect new hosts. The emergence of infectious life stages often occurs once a day to minimize mortality in adverse environments. In bird hosts, intestinal parasites such as coccidia are generally released with feces in the late afternoon. This dynamic is adaptive since it allows avoiding desiccation and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, thus reducing mortality of oocysts in the environment until transmission to the next host. If this circadian rhythm is the result of natural selection to increase oocyst survival, we may hypothesize that oocysts will appear in feces at different times depending on the environment where hosts live. Particularly, in an environment where UV radiation and desiccation are very low, we may expect oocyst circadian release to disappear since the main selective pressure would be relaxed. We sampled different species of birds in tropical and temperate forests in spring and investigated coccidian oocyst output. A strong circadian variation in the prevalence of hosts shedding coccidian oocyst was detected for species caught in the temperate forest with an increase in prevalence in the late afternoon, whereas prevalence of birds shedding oocysts was constant over the course of the day for most species sampled in the tropical rain forest. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that oocysts’ circadian output is maintained by natural selection to increase oocyst survival. We discuss the adaptive significance of diurnal periodicity in parasite output.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press

References

- 2

- Cited by