Introduction

Advanced cancer can be defined as cancer which is not likely to be cured or controlled by treatment. It may be accompanied by intense physical symptoms, including pain and fatigue, and symptoms of psychological distress, which result in reduction in activity and impairment of the quality of life (QoL) (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Butow and Costa2014). Pain is the symptom most frequently reported in advanced cancer, at rates ranging from 24% to 99.2%, and it is also the most overwhelming symptom, affecting the full spectrum of the dimensions of QoL in patients with cancer (van den Beuken-van Everdingen et al., Reference van den Beuken-van Everdingen, Hochstenbach and Joosten2016). For these patients, pain, apart from restricting activities, is a constant reminder of the worsening of their illness, and it is accompanied by the need for ever stronger doses of analgesics, and often by the disappointment of the attending doctors (Syrjala et al., Reference Syrjala, Jensen and Mendoza2014).

In addition to pain, patients with advanced cancer, and especially those aged over 65 years, often report fatigue, anorexia, and sleeplessness, problems that may be related to comorbid psychopathology, mainly anxiety and depression, which, in turn, may aggravate the physical symptoms, and which exert a profound adverse impact, not only on their QoL, but even on their survival (Mystakidou et al., Reference Mystakidou, Pappa and Tsilika2008; Parpa et al., Reference Parpa, Tsilika and Gennimata2015). Despite such evidence, the proportion of patients with advanced cancer who receive treatment for depression is low, possibly because the symptoms may be interpreted as a normal grief reaction to the progress of cancer (Mystakidou et al., Reference Mystakidou, Pappa and Tsilika2008). Other than depression and anxiety, little investigation has been reported on other symptoms of psychological distress and their effects on these patients, although studies have focused on coping strategies, grief, spiritual needs, and religious beliefs (Vallurupalli et al., Reference Vallurupalli, Lauderdale and Balboni2012; Greer et al., Reference Greer, Applebaum and Jacobsen2020).

In order to improve the QoL of patients with advanced cancer, it is important to assess their perceptions of their ability to enjoy activities of everyday life, using reliable and clinically useful instruments. One of the generic QoL instruments is the brief World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) which enables rapid assessment of the QoL and has been widely used in clinical studies (Skevington and McCrate, Reference Skevington and McCrate2012). The psychometric properties of this instrument have been evaluated in patients with a variety of types of cancer and at different phases of the disease progression (Van Esch et al., Reference Van Esch, Den Oudsten and De Vries2011; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Yang and Lai2017), but to the best of our knowledge, there is little documentation of its psychometric properties in patients with advanced cancer. A recent study testing the psychometric characteristics of the WHOQOL-BREF in patients with advanced cancer in Vietnam recorded excellent internal consistency, reliability, and discriminant validity (Huyen et al., Reference Huyen, Van Anh and Duong2021), and satisfactory psychometric properties of this instrument were also demonstrated in a sample of patients with advanced stage lung cancer (de Mol et al., Reference de Mol, Visser and Aerts2018).

The aims of the present study were (i) to evaluate the psychometric characteristics of the Greek version of WHOQOL BREF in patients with advanced cancer and pain and (ii) to explore the impact of a wide range of symptoms of psychological distress on the QoL of these patients.

Methods

Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted among adult patients with advanced cancer who were attending an out-patient oncology pain clinic in a tertiary care hospital. The inclusion criteria included: age <75 years, a diagnosis of advanced cancer, absence of curative intent treatment, ability to read and complete the questionnaires, absence of significant cognitive deficit being evaluated by clinical interview, and no history of administration of antidepressant or other psychiatric medication. Of the 162 patients who fulfilled the criteria and were invited to participate, 11 patients were excluded because of missing data, 6 declined, and 145 agreed to participate. The participants were informed about the aims of the study and provided their written informed consent. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the European guidelines for clinical practice.

Study instruments

The participants completed the following instruments:

1. The WHOQOL-BREF. This consists of 26 items and two questions for the assessment of the overall QoL and general health. It provides information in four domains: Physical Health, Psychological Health, Social Relationships, and Environment. The responses are given on 5-point Likert scale (1–5), and the overall score ranges from 0 to 100; a higher score corresponds to better QoL. The original English language version demonstrated good internal consistency/reliability, with Cronbach's alpha (α) 0.66–0.84 (WHOQOL Group, 1998). The instrument has been translated and validated for use in the Greek population, demonstrating internal consistency similar to the original version (Physical Health: Cronbach's α = 0.80, Mental Health: α = 0.79, Social Relationships: α = 0.65, Environment: α = 0.66) (Ginieri-Coccossis et al., Reference Ginieri-Coccossis, Triantafillou and Tomaras2012). It has been used as an outcome measure of QoL in Greek people with a variety of health conditions (Paika et al., Reference Paika, Almyroudi and Tomenson2010; Siarava et al., Reference Siarava, Hyphantis and Katsanos2019; Saridi et al., Reference Saridi, Toska and Latsou2022).

2. The Symptom Checklist (SCL-90): This is designed to assess a wide range of psychological distress symptoms in psychiatric and medical patients (Derogatis et al., Reference Derogatis, Lipman and Covi1973). It consists of 90 items, which evaluate the degree of intensity of symptoms in nine dimensions of general mental health: somatization, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. It also includes a category of “additional items,” covering other symptoms, including sleep problems and poor appetite. These items contribute to the global score of the instrument but are not scored as a dimension. Apart from scores on each subscale, the instrument provides the Global Severity Index (GSI), which reflects the intensity of perceived distress as a single number. The GSI is the summary measure of the nine dimensions and has been widely used as the overall measurement of psychological distress. The responses are given on a five-point Likert scale, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). A high score is indicative of a high degree of intensity of symptoms. It should be noted that SCL-90 is not intended for diagnostic purposes, and the scores do not indicate psychiatric disorders. It has been used in a broad spectrum of populations as an outcome measure (Khalifa et al., Reference Khalifa, Gibbon and Völlm2020; Leichsenring et al., Reference Leichsenring, Jaeger and Masuhr2020; Carrozzino et al., Reference Carrozzino, Christensen and Patierno2021), as a psychiatric screening instrument (Rytilä-Manninen et al., Reference Rytilä-Manninen, Fröjd and Haravuori2016; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Stavropoulos and Christidi2021), and as a brief measurement of mental health in non-psychiatric populations (Sereda and Dembitskyi, Reference Sereda and Dembitskyi2016; Dorresteijn et al., Reference Dorresteijn, Gladwin and Eekhout2019; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Wang and Sun2020). The use of SCL-90 as an indicator of mental health in samples of oncology patients has been well documented (Recklitis et al., Reference Recklitis, Licht and Ford2007; Paika et al., Reference Paika, Almyroudi and Tomenson2010). The instrument has been translated and validated for use in the Greek population, with Cronbach's α ranging from 0.69 to 0.91 (Donias et al., Reference Donias, Karastergiou and Manos1991; Kostaras et al., Reference Kostaras, Martinaki and Asimopoulos2020).

3. The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for estimation of pain. This is in the form of a horizontal line 100 mm in length, the left end of which designates “no pain” and the right end “extremely severe pain.” The patients are asked to indicate the point on the line that best indicates the degree of pain that they are feeling at the specific point in time. The cut-off points for categorization are: no pain (0–4 mm), mild pain (5–44 mm), moderate pain (45–74 mm), and severe pain (75–100 mm). A score of >45 mm is considered as clinically significant pain (Scott and Huskisson, Reference Scott and Huskisson1976).

Statistical analysis

In analysis, the following methods were used; firstly for testing the reliability of the instruments: (a) Cronbach's alpha (for internal consistency) and (b) Item Response Theory (IRT; Lord, Reference Lord1980; Bartholomew et al., Reference Bartholomew, Knott and Moustaki2011). IRT relates the respondent's answers to the items of an instrument to that person's ability level in that domain. It considers both the difficulty of each item and the inter-item correlations, while classical test theory gives the same weight to all items of an instrument. The IRT logistic model for ordinal variables on a k-Likert scale that was used here yields a discrimination parameter and k–1 difficulty parameters for each ordinal item with k categories (Moustaki et al., Reference Moustaki, Jaereskog and Mavridis2004). The discrimination parameter is similar to the factor loading in a classical factor analysis and represents the way in which the probability of a positive response to that item changes with increasing ability level. The larger the discrimination parameter for an item, the higher the correlation between the item and the (measured construct) latent variable. Another important output of IRT analysis is that each subject is measured on the hypothetical scale. This means that we take a factor score that tells us how high/low a subject is on the scale measured by the instrument. These factor scores can subsequently be used for specific analytical testing (e.g., regression analysis), (c) Correlation coefficients: we used the polychoric correlation between two ordinal variables, the Pearson correlation between two continuous variables and polyserial correlation between a continuous and an ordinal variable. For variables for which none of the correlation coefficients could be applied, a t-test was applied for independent samples, or an analysis of variance with multiple comparisons under the Bonferroni criterion, after appropriate normality tests, and (d) Linear regression: Statistical models associate a dependent variable to one or several independent variables. The factor scores of the four domains of WHOQOL-BREF were used as outcomes/dependent variables. The backward elimination method using AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) was applied to select those covariates that have an association with the outcomes. We used R packages «MASS» for linear regression with AIC and «ltm» for Item Response Theory.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The study sample consisted of 145 patients with advanced cancer and pain ranging in age from 32 to 75 years, mean 62.8 ± 9.39 years, whereas the majority (57.9%) were male. According to their pain rating on the VAS, 84.7% experienced moderate to intense pain at the time of assessment (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study patients with advanced cancer and pain (N = 145)

SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analogue scale for pain; VAS categorization: No pain: 0–4 mm, Mild: 5–44 mm, Moderate: 45–74 mm, Severe: 75–100 mm.

Quality of life and psychological distress

The domains of WHOQOL-BREF in which the lowest mean scores were recorded were Physical Health (32.40 ± 20.61) and Psychological Health (47.41 ± 20.16). The mean scores in the domains of Social Relationships and Environment were 65.05 ± 17.23 and 66.25 ± 13.91, respectively. Regarding the scores on SCL-90, the three dimensions for which the highest scores were recorded were depression (1.67 ± 0.84), somatization (1.25 ± 0.57), and anxiety (1.07 ± 0.68). The scores on the WHOQOL-BREF domains and the SCL-90 dimensions are displayed in Figure 1 as barplots with error bars.

Fig. 1. Error bars displayed on barplots for the dimensions of SCL-90 and WHOQOL-BREF domains. The edges of the error bars is the standard deviation and represents the amount of dispersion in every variable.

Reliability of internal consistency of the WHOQOL-BREF

The reliability of internal consistency was high for all domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. Specifically, the Cronbach's α for the four domains were: Physical 0.915, Psychological 0.879, Social Relationships 0.731, and Environment 0.823.

Item Response Theory (IRT)

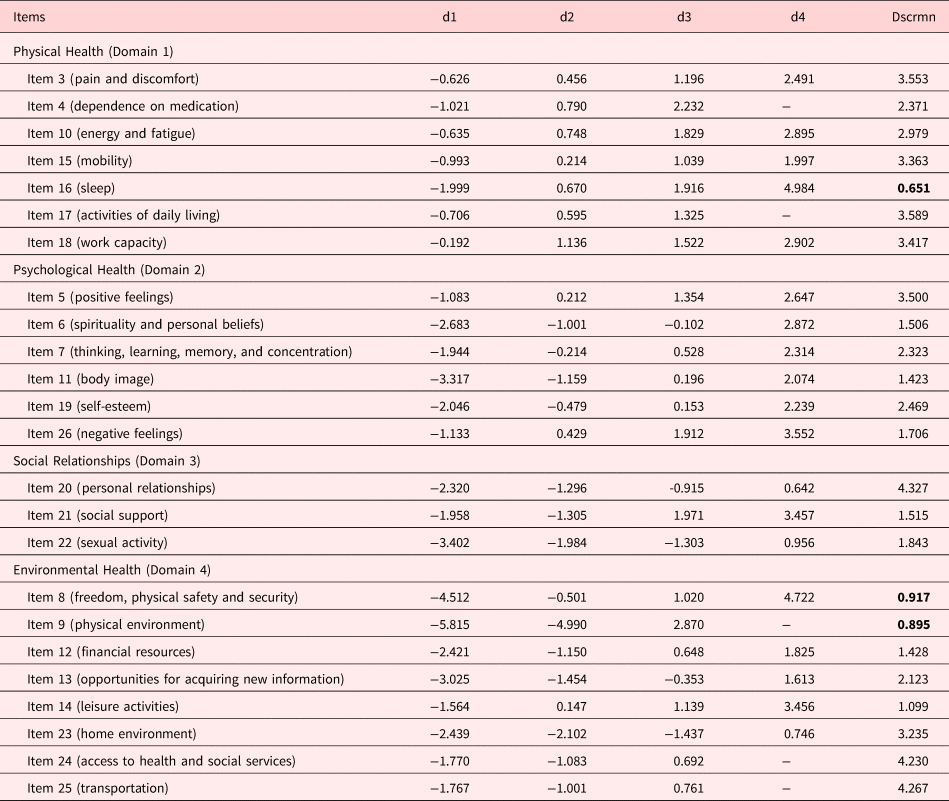

IRT was applied to each of the domains of WHOQOL. Table 2 summarizes the IRT results, showing the threshold and discrimination parameters for all the items in all four dimensions. Supplementary Appendix Figure 1 shows the item information curves for all the items in the four domains of WHOQOL-BREF. Item 16 (Sleep) of Domain 1 (Physical Health) showed the smallest discrimination coefficient, indicating that it is the least informative item in this domain. This is also evident in Supplementary Appendix Figure 1 where the item information function is shown as a straight line throughout the ability level of a patient, implying that it provides no information irrespective of the level of physical health. Similar results can be seen in Domain 4 (Environment) for the items 8 (Freedom, Physical Safety, and Security) and 9 (Physical Environment). For Domains 2 (Psychological Health) and 3 (Social Relationships), all the items showed high discrimination parameters. In the subsequent regression analysis to explore associations of the four domains of the WHOQOL-BREF, the factor scores derived from the IRT were used, rather than the raw scores.

Table 2. IRT parameter estimates for the scales of the 24-item WHOQOL-BREF

The bold discrimination factor indicates that the value of this factor is less than one and therefore not that informative for the latent variable.

d, the difficulty parameter; Dscrmm, the discrimination parameters.

Correlation coefficients

Figure 2 shows the polychoric, Pearson and polyserial correlations between the four factor scores of WHOQOL-BREF and age, duration of the disease, pain VAS rating, scores on the SCL-90 dimensions and GSI. The scores on the SCL-90 dimensions were negatively correlated with the factor scores in all the WHOQOL-BREF domains. Depression showed strong significant negative correlation with the factor scores of Physical Health (−0.72) and Psychological Health (−0.74) and with the indices Overall QoL (−0.65) and General Health (−0.68). Strong correlation was observed between GSI and Overall QoL (−0.61), General Health (−0.66), Physical Health (−0.68), and Psychological Health (−0.72). Age, VAS pain rating, and disease duration appeared to have no correlation with factor scores on any of the WHOQOL-BREF domains.

Fig. 2. Correlation table of the factor scores of WHOQOL-BREF with the symptoms checklist-90 (SCL-90), age, VAS pain, and duration. The size and the color scale of the circle in the correlation table, express the magnitude, and the sign of the correlation, respectively.

Table 3 shows the results of univariable analysis exploring the association between the four WHOQOL-BREF factor scores and specific patient characteristics. The educational level showed positive association with the scores on Physical Health (p = 0.047), Social Relationships (p = 0.003), and Environment (p = 0.002), and family status with the scores on Social Relationships (p = 0.010) and Environment (p < 0.001). These univariable statistically significant associations disappeared when we accounted for other variables in a multivariable regression model (Table 4).

Table 3. Report of statistical significan-t differences among factor scores of the domains and demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients with advanced cancer and pain (N = 145)

a Independent samples T-test.

b ANOVA; F = F-test; t = T-test; SD = standard deviation.

Table 4. Statistically significant effects on four factor score domains (WHOQOL-BREF) in the study patients with advanced cancer and pain (N = 145)

R 2 Adj, R 2 Adjusted; B, unstandardized coefficient; Std. Error, Standard Error; GSI, Global Severity Index.

B unstandardized coefficient for the quality of life factor scores outcomes after Backward Elimination with AIC (Akaike information criterion) as stopping rule criterion. Note that the p-value considered from the AIC stopping rule is 0.157. This explains why some variables stayed in the model although they had a p-value larger than 0.05.

Multivariable linear regression analysis

As univariable analysis may be subject to confounding effects, providing spurious correlations, we conducted multivariate regression analysis using the four WHOQOL-BREF factor scores as outcomes and various patient characteristics as covariates. Because of the small number of participants, we restricted the number of covariates to seven: age, gender, type of cancer, metastases, pain VAS rating and disease duration (for clinical-demographic characteristics), and the GSI. GSI was shown to be significantly negatively associated with all four factor scores. Ηigher GSI was associated with lower scores on Physical Health (B = −1.488, p < 0.001), Psychological Health (B = −1.688, p < 0.001), Social Relationships (B = −0.910, p < 0.001), and Environment (B = −1.064, p < 0.001). Male gender was correlated with lower scores on Social Relationships (B = −0.358, p = 0.007) and Environment (B = −0.293, p = 0.026) (Table 4).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the psychometric characteristics of the Greek version of WHOQOL-BREF in patients with advanced cancer and pain. In addition, the effect of a wide range of symptoms of psychological distress on QoL in these patients was explored.

The results showed that the internal consistency was high for all domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. Numerous similar studies in different patient populations and in different languages have shown good internal validity of the questionnaire (Su et al., Reference Su, Ng and Yang2014; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Li and Lin2016; Balalla et al., Reference Balalla, Medvedev and Siegert2019; Pomeroy et al., Reference Pomeroy, Tennant and Mills2020; Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Chaveiro and de Freitas2021; Kalfoss et al., Reference Kalfoss, Reidunsdatter and Klöckner2021). The domain with the lowest, but still adequate, Cronbach's α was Social Relationships. This finding is consistent with the results of the initial standardization of the instrument in the Greek language (Ginieri-Coccossis et al., Reference Ginieri-Coccossis, Triantafillou and Tomaras2012), and with other studies, in which the Cronbach's α for this domain was even lower (de Mol et al., Reference de Mol, Visser and Aerts2018; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Hwang and Wang2019; Huyen et al., Reference Huyen, Van Anh and Duong2021). One possible explanation is the small number of items in the Social Relationships domain.

IRT was applied to explore the psychometric characteristics of each of the domains of WHOQOL. According to the results, item 16 (Sleep) of Domain 1 (Physical Health) had the smallest discrimination coefficient, indicating that it is the least informative item in this domain. This is easily understood, as sleep disorders are common in patients with advanced cancer (Mercadante et al., Reference Mercadante, Aielli and Adile2015; Davies, Reference Davies2019). Similar results were seen in Domain 4 (Environment) for the items 8 (Freedom, Physical Safety and Security) and 9 (Physical Environment). One possible explanation for these findings is that all the participants were recruited from the same hospital that covers the needs of the inhabitants of a mountainous region characterized by a good, quiet natural and built environment, and underwent no changes in their environmental well-being. In the other two Domains, 2 (Psychological Health) and 3 (Social Relationships), all the items showed high discrimination parameters. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is a gap of evidence about the psychometric evaluation of the WHOQOl-BREF in Greek using modern test theories. However, similar studies showed diverse results probably because of the cultural disparities and the different populations surveyed. Specifically, WHOQOL-BREF had three misfit items in a heroin-dependent sample (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Wang and Tang2014), low to moderate discrimination parameters for all items in Farsi version administered in undergraduates students (Vahedi, Reference Vahedi2010) and no misfit items in the general population (Krägeloh et al., Reference Krägeloh, Kersten and Rex Billington2013), in community-dwelling elderly people (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Chang and Yeh2009) or in outpatients with five types of cancer (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Hwang and Wang2019).

It was shown that the participants perceived their QoL as poor, especially in the domains of both Physical and Psychological Health. A large body of evidence indicates that the QoL of patients with cancer deteriorates significantly with the worsening of the symptoms of their illness and is also affected by the accompanying psychological burden, thus highlighting the improvement of the psychological state as a primary goal in their management (Haun et al., Reference Haun, Estel and Rücker2017; Kassianos et al., Reference Kassianos, Ioannou and Koutsantoni2018; Verkissen et al., Reference Verkissen, Hjermstad and Van Belle2019; Crespo et al., Reference Crespo, Rodríguez-Prat and Monforte-Royo2020).

The correlation coefficients revealed depression to be significantly associated with the QoL in patients with advanced cancer and pain. Specifically, depression showed strong negative correlation with the domains of Physical and Psychological Health. These findings are in line with the results of the initial WHOQOL-BREF validation in the Greek population, which demonstrated a significant association between depression, as assessed by the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), with the domains of Physical Health and Psychological Health (Ginieri-Coccossis et al., Reference Ginieri-Coccossis, Triantafillou and Tomaras2012).

Depression has been documented in high proportions of patients with advanced cancer and high levels of comorbidity, especially in those experiencing severe pain and other serious physical symptoms, such as fatigue and dyspnea (Newcomb et al., Reference Newcomb, Nipp and Waldman2020). The experience of severe unpleasant symptoms may lead to deterioration in the overall state of health, resulting in the illness being perceived as a serious threat, raising the issue of dependency on others, and reinforcing the interplay between physical symptoms and psychological distress (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Janevic and Kershaw2017).

It should be emphasized that depression in patients with advanced cancer is closely associated with the preparatory phase of bereavement and grief, and distinction between the two is often extremely difficult (Parpa et al., Reference Parpa, Kostopoulou and Tsilika2019). Preparatory grief is a normal process of adaptation at the spiritual, psychological, organic, and social level and encompasses existential loneliness, despair, social withdrawal, and distancing from friends and relatives (Mystakidou et al., Reference Mystakidou, Pappa and Tsilika2008; Vergo et al., Reference Vergo, Whyman and Li2017).

Based on the results of multivariable regression analysis, GSI can be considered an independent determinant of QoL in patients with advanced cancer and pain. It is apparent that the disease process can activate multiple physiological and psychological mechanisms that lead to a wide range of psychological distress symptoms (Lutgendorf and Sood, Reference Lutgendorf and Sood2011; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Sloan and Antoni2022). Anxiety about the worsening of the disease and the experience of pain may generate generalized disruption of the balance, with a combination of physical and psychological responses, effected via complex mechanisms (Hyphantis et al., Reference Hyphantis, Paika and Almyroudi2011). In this study, the pain did not appear to exert a direct significant effect on the QoL, and any impact was probably mediated by the emotional response to pain, with aggravation of depressive symptoms (Dersh et al., Reference Dersh, Polatin and Gatchel2002).

Male gender was associated with poor perceived network of interpersonal and social relationships and with poor QoL related to the domain of Environment (sense of security, financial status, received information, and natural environment). It is well known that the social structure of a culture determines the roles and position of the genders and the differences related to health and QoL (Mayor, Reference Mayor2015; Matud, Reference Matud and Alvinius2017). These differences are more pronounced in the elderly and at the end of life, as this stage is marked by transitions and changes in social roles and family relationships that may have a greater impact on men (Carmel, Reference Carmel2019; Ullrich et al., Reference Ullrich, Grube and Hlawatsch2019).

A result of the typical male socialization process, men are expected to be assertive, independent and emotionally inexpressive, avoiding showing weakness. They are therefore less likely to seek psychological support, and often become isolated from the people around them, resulting in increased depression (Lapid et al., Reference Lapid, Atherton and Kung2013; Seifart et al., Reference Seifart, Riera Knorrenschild and Hofmann2020). For the interpretation of the findings related to gender, it is of note that the study sample comes from a mountainous region, with a culture characterized by traditional family roles, in which the man continues to be the “breadwinner” of the house (Mayor, Reference Mayor2015; Matud et al., Reference Matud and Alvinius2017). In this context, the impact of inability to work due to illness, and of the perceived lack of strong interpersonal and social support, on their QoL can be better understood (Carmel, Reference Carmel2019).

It has been observed that interpersonal relationships, both with family members and in the wider social environment, constitute an important source of meaning of the disease experience (Scheffold et al., Reference Scheffold, Mehnert and Müller2014). A direct relationship between symptoms of psychological distress and loss of the meaning of life has been documented (Lee and Loiselle, Reference Lee and Loiselle2012) which should be taken into consideration in the design of interventions to improve the QoL of the patients with advanced cancer (Tomás-Sábado et al., Reference Tomás-Sábado, Villavicencio-Chávez and Monforte-Royo2015).

Many of those who attend a pain clinic, indeed, express the experience of existential agonizing and suffering. Several studies document that spiritual pain, namely the emotional distress that results from the severance of the relationship of individuals with themselves, with others and with God, known as relational rupture, exerts a profound negative effect on the QoL of patients with advanced cancer (Jim et al., Reference Jim, Pustejovsky and Park2015; Leigh-Hunt et al., Reference Leigh-Hunt, Bagguley and Bash2017; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Mosher and Winger2018; Pérez-Cruz et al., Reference Pérez-Cruz, Langer and Carrasco2019). How is “meaning” interpreted in this context? The putting of their affairs in order, the facilitation of expression of their emotions, and the enhancement of their relations with the important others in their lives, are some of the possible answers (Gonen et al., Reference Gonen, Kaymak and Cankurtatan2012; Estacio et al., Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2018).

To sum up, palliative care interventions for patients with advanced cancer should focus on identifying and alleviating their psychological distress, determining the sources of meaning for each patient, with a gender sensitive approach, in order to facilitate the incorporation of this meaning into their lives and to contribute to their best possible adaptation to the situation and the improvement of their QoL (Lorenz et al., Reference Lorenz, Lynn and Dy2008; Sheinfeld et al., Reference Sheinfeld, Krebs and Badr2012).

Strengths and limitations

This study had certain limitations. First, it was cross-sectional, making it not possible to investigate causal relationships, but this is a limitation which applies to most of the similar studies. Second, the sample was relatively small, and all the patients were recruited from a single out-patient oncology pain clinic, which limits the generalization of the study findings.

Despite these limitations, a key strength of the present study was the use of modern test theory, IRT, to describe the psychometric characteristics of the WHOQOL-BREF in Greek patients with advanced cancer and pain. Another strength of the study was the use of the SCL-90, a questionnaire widely used to estimate psychological distress in clinical practice. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the SCL-90 has not been administered to a similar group of patients, although it has been used with other patients with cancer.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the Greek version of WHOQOL-BREF has good psychometric properties in patients with advanced cancer and pain, and that it can provide a comprehensive evaluation of their QoL in daily clinical practice. In addition, the study contributes to our understanding of the psychological distress symptoms in these patients. The deterioration of the illness activates multiple mechanisms, leading to the expression of a wide range of symptoms of psychological distress, with negative effects on the QoL, generating considerable needs for personalized palliative care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951522001055.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.