Introduction

Existential distress is common among people suffering from a serious and incurable disease (Kelley Reference Kelley2014; Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021). This distress includes symptoms of depression, anxiety, demoralization, and loss of meaning (LeMay and Wilson Reference LeMay and Wilson2008). Common intervention modalities to alleviate this distress in palliative care include pharmacotherapy (notably antidepressants and anxiolytics), psychotherapy, and spiritual guidance (LeMay and Wilson Reference LeMay and Wilson2008; Radbruch et al. Reference Radbruch, De Lima and Knaul2020). Unfortunately, these approaches have limited effectiveness (Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Gibson and Poppito2004; Byock Reference Byock2018; Doyle Reference Doyle1992; Kelley Reference Kelley2014; LeMay and Wilson Reference LeMay and Wilson2008; Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021; Ostuzzi et al. Reference Ostuzzi, Matcham and Dauchy2018; Stone et al. Reference Stone, Yaseen and Miller2022; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Guo and Chen2023) or are not very accessible (Keall et al. Reference Keall, Clayton and Butow2015). In such cases, continuous palliative sedation and medical assistance in dying (MAID) may be considered as a last resort (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Kristjanson and Ashby2006; Rodrigues et al. Reference Rodrigues, Crokaert and Gastmans2018; Société québecoise des médecins de soins palliatifs. Collège des médecins du Québec 2015). Recently, a new treatment has offered hope to people suffering from existential distress: psilocybin-assisted therapy (Agin-Liebes et al. Reference Agin-Liebes, Malone and Yalch2020; Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Johnson and Carducci2016; Grob et al. Reference Grob, Danforth and Chopra2011; Hendricks et al. Reference Hendricks, Johnson and Griffiths2015; Spiegel Reference Spiegel2016).

Briefly, psilocybin-assisted therapy occurs in 3 phases: (1) a preparation period; (2) the administration of a high dose of psilocybin in a safe, aesthetically pleasing, and comfortable environment with 2 therapists; and (3) an integration period. Treatment is repeated if necessary. Clinical studies have shown that psilocybin, taken within such a psychotherapeutic framework, can induce rapid, significant, and long-lasting relief of anxiety and depression in patients suffering from existential distress (Nichols Reference Nichols2016; Nygart et al. Reference Nygart, Pommerencke and Haijen2022; Ross et al. Reference Ross, Agin-Liebes and Lo2021; Schimmel et al. Reference Schimmel, Breeksema and Smith-Apeldoorn2022; Yaden et al. Reference Yaden, Nayak and Gukasyan2022). These benefits could improve the condition of patients suffering from this end-of-life distress, and the benefits seem to last beyond 6 months (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Bossis and Guss2016; Whinkin et al. Reference Whinkin, Opalka and Watters2023). Despite the intensity of its psychoactive effects, psilocybin is a substance with a wide margin of physical and psychological safety when administered in a supervised setting (Byock Reference Byock2018; Grob et al. Reference Grob, Danforth and Chopra2011; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Richards and Griffiths2008; Nichols Reference Nichols2016). However, those considering psilocybin-assisted therapy must meet certain criteria, notably the absence of personal or particular family psychiatric histories such as psychosis and bipolar disorder.

Since 2022, Health Canada, the department responsible for federal health policy in Canada, has allowed physicians to request psilocybin for their patients suffering from refractory depression and end-of-life distress through the Special Access Program (SAP). To be eligible, the patient must be suffering from a serious or life-threatening illness and must have already tried conventional treatments, whether these have failed, are unsuitable or unavailable. Physicians must complete and submit a patient-specific form, after which the SAP evaluates requests on a case-by-case basis. (Government of Canada 2022). Despite Canada’s loosening restrictions, access to psilocybin-assisted therapy remains limited (Patchett-Marble et al. Reference Patchett-Marble, O’Sullivan and Tadwalkar2022). Several issues are limiting the rollout of this therapy and its integration into healthcare networks (Beaussant et al. Reference Beaussant, Sanders and Sager2020, Reference Beaussant, Tulsky and Guérin2021; Mayer et al. Reference Mayer, LeBaron and Acquaviva2022; Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Barnett and Weleff2022; Rosa et al. Reference Rosa, Hope and Matzo2019, Reference Rosa, Sager and Miller2022). The restrictive legislative and bureaucratic context seems to be at the root of several of them (Beaussant et al. Reference Beaussant, Tulsky and Guérin2021; Byock Reference Byock2018; Hartogsohn Reference Hartogsohn2017). Moreover, very few healthcare professionals are trained to offer it to their patients.

Given the growing public interest and medical enthusiasm for this approach (Barber and Aaronson Reference Barber and Aaronson2022; Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021), we anticipate that this treatment will be increasingly considered and requested by people facing a serious and incurable disease. Since the broader implementation of psilocybin-assisted therapy within palliative care will also depend on the attitudes of healthcare providers willing to recommend it, healthcare professionals should be actively engaged in the wider discussion about this treatment option. A few studies have documented palliative care professionals’ perceptions of psychedelic therapies (Beaussant et al. Reference Beaussant, Tulsky and Guérin2021; Mayer et al. Reference Mayer, LeBaron and Acquaviva2022; Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Akroyd and Sundram2021, Reference Reynolds, Barnett and Weleff2022), but few have focused specifically on psilocybin (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Meir and Lex2022). In addition, most focused on the attitudes of professionals in a context where PAT was not yet integrated into the care system outside of clinical studies. Our study is the first to have been carried out at a time when this treatment is accessible in an universal healthcare system, which enables us to identify more concrete issues in terms of acceptability and access in the palliative care context.

The aims of our research were (1) to identify issues and concerns regarding the acceptability of this therapy among palliative care professionals and to discuss ways of remedying them; and (2) to identify factors that may facilitate access.

Methods

This qualitative study is reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines (see Supplementary Materials).

Design

The World Café is a data-gathering method used in qualitative research, characterized by providing an informal environment conducive to creative and collaborative exchange. It enables people from various backgrounds and viewpoints to discuss “questions that matter” (Fouché and Light Reference Fouché and Light2011). The World Café is used to identify environmental and contextual needs, analyze and resolve situations, or provide solutions to questions posed (Brown and Isaacs Reference Brown and Isaacs2005; Löhr et al. Reference Löhr, Weinhardt and Sieber2020) because it assumes that participants are “experts” (Fouché and Light Reference Fouché and Light2011). This technique also has the advantage of shortening data collection times compared with conventional qualitative methods (Schiele et al. Reference Schiele, Krummaker and Hoffmann2022).

Recruitment and participants

The objective was to bring together healthcare participants with expertise in various fields who devoted a significant part of their professional activities to palliative and end-of-life care. Thus, we conducted purposive sampling by emailing targeted invitations to palliative care professionals identified from palliative care networks. This sampling method allows for identifying and selecting participants who have knowledge and expertise and are familiar with the context (i.e., palliative care), as they are more likely to provide applicable and useful information (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Greenwood and Prior2020; Palinkas et al. Reference Palinkas, Horwitz and Green2015). The attitudes of professionals toward psilocybin-assisted therapy were not known at the time they were invited to participate, but none were involved in any way with this treatment.

Discussion guide

A literature review was first carried out to develop the themes to inform the World Café questions. Two main questions were developed by the World Café research committee (MD, MMG, SLC, LP, JSF, and JH), with sub-questions to be addressed under each. The first question centered on acceptability, while the second explored access (Box 1). These questions were developed to stimulate opinions, exchanges, and debates about how this therapy is perceived among healthcare professionals currently in practice and to identify priorities or issues to consider regarding access. Questions were finalized by consensus, and an accompanying discussion guide was developed with guidelines and prompts for table hosts (see Supplementary Materials).

Box 1. World Café questions

Theme 1: Acceptability

Question: From what you know, what do you think of psilocybin-assisted therapy as a treatment for existential distress in palliative care?

Sub-question: How can we make psilocybin-assisted therapy more acceptable to palliative care professionals?

Theme 2: Access

Question: In your opinion, should access to this therapy be made easier for people experiencing existential distress?

Sub-question: If so, how could this be achieved? If not, why not?

Data collection

Consenting participants received general information about psilocybin-assisted therapy prior to the event to facilitate forthcoming discussions. These lay documents come from independent, credible sources of scientific information (Courniou Reference Courniou2021; Gris Roy Reference Gris Roy2022).

The event was held at a hall at Université Laval, Québec, Canada. The venue is known for hosting university events and was chosen for its hospitable setting, geographical location, and the needs of the research team and participants.

The World Café took place on April 24, 2023. The event began with a presentation by a physician (JFS) who has integrated psilocybin-assisted therapy into his practice, followed by a question period. Ground rules and instructions were presented to participants before the activity began (JH, MD). Participants were purposely assigned into groups of 3 or 4 per table for each round before the activity took place, accompanied by a host and a note-taker (Brown and Isaacs Reference Brown and Isaacs2005). The role of table hosts (MMG, SLC, LP, FP, AB) was to welcome participants and facilitate exchanges according to the discussion guide. They were part of the research team, had no previous connections to the participants, were previously trained, and were asked to remain neutral (Schiele et al. Reference Schiele, Krummaker and Hoffmann2022). Note-takers were research assistants. The addition of a note-taker per table ensured more complete data collection. Their role was to capture parts of the conversation, themes, main ideas, and questions emerging from the discussions (Schiele et al. Reference Schiele, Krummaker and Hoffmann2022). Table hosts also took notes during the discussions. Sticky notes were also available for participants at each table to document all other thoughts and questions. Due to the sensitive nature of the topic, no audio recording was used (Löhr et al. Reference Löhr, Weinhardt and Sieber2020; McGrath et al. Reference McGrath, Kennedy and Gibson2023). In addition, the location in which the event took place would have compromised the quality of the recordings. Two questions were posed (see Box 1) by the World Café host (JH), and participants had 30 minutes to discuss each. At the end of a round, table hosts and note-takers summarized the main discussion points and validated their accuracy with table participants. When prompted by the World Café host, the participants moved to their next assigned table. Hosts and note-takers remained at their tables to welcome the new participants and ensure the continuity of discussions. At the end of both discussion rounds, a large group exchange took place to share experiences, ask follow-up questions, and bring the discussion to a close with a final word on the implications of this therapy in palliative care (JH, PD).

Data analysis

All discussions were conducted and documented in French. Illustrative quotes were translated into English by the authors. Note-takers’ transcripts and sticky notes were transcribed by author MMG, who is familiar with qualitative methods. The data was analyzed inductively (MMG) following Braun and Clark’s 6-step approach (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun, Clarke, Cooper, Camic and Long2012): (1) familiarization with the data; (2) identification of initial codes; (3) search for themes from the initial codes; (4) discussion and revision of themes; (5) definition of themes; (6) final analysis and drafting of a coherent set linking the themes. Several trustworthiness strategies were used to ensure data credibility (Lincoln and Guba Reference Lincoln and Guba1986; Varpio et al. Reference Varpio, Ajjawi and Monrouxe2017), including a wrap-up summary with table participants at the end of each round and a follow-up meeting following the World Café to debrief and consider different team members’ perspectives during the analysis. After transcripts were coded (MMG), 10% were check-coded by another team member (AB) to enhance design reliability and internal validity (intercoder agreement 84%) (Kohn and Christiaens Reference Kohn and Christiaens2014; Raskind et al. Reference Raskind, Shelton and Comeau2019). Identified discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. All analyses were performed using NVivo software.

Results

We aimed for at least 15 participants, and 19 were recruited, of whom 16 participated in the event. Three participants were unable to attend due to illnesses, including COVID-19.

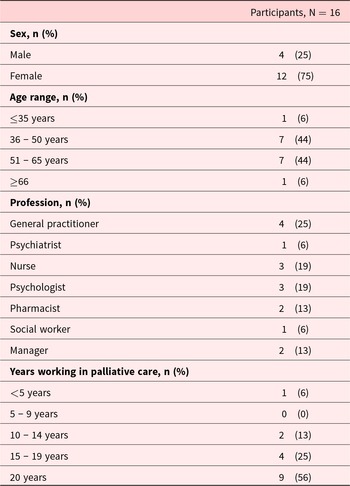

Participants represented different professions in palliative care: 5 physicians, including 1 psychiatrist, 3 nurses, 3 psychologists, 2 pharmacists, 1 social worker, and 2 health care managers. Most participants were female (75%), about half were >50 years old (50%), and most had ≥10 years of experience working in palliative care (94%). Characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants

Professional attitudes toward psilocybin-assisted therapy

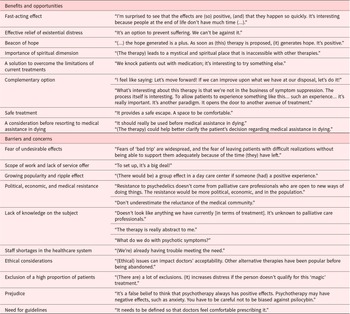

Themes, sub-themes, and the corresponding quotes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes and subthemes with representative quotes regarding the acceptability of psilocybin-assisted therapy in palliative care

Benefits and opportunities

Most participants considered psilocybin-assisted therapy a promising treatment for the relief of existential distress. Its rapid onset of action and effectiveness fill a need in palliative care. They mentioned that they felt unprepared for the distress experienced by people with incurable illnesses and that they were unable to help them with traditional methods, especially in a time-sensitive context.

It was noted that the spiritual or mystical dimension is often neglected in care environments despite the important role it could play in dealing with existential distress. Many welcome the presence of this dimension in psilocybin-assisted therapy, and some see it as a potential addition to their therapeutic arsenal.

According to some, physical pain is not always the main symptom in palliative care, and one reason for seeking MAID is often psychological suffering. The absence of effective treatment was said to be why some patients seek this last-resort intervention. In such a context, psilocybin-assisted therapy could give people new hope with much to gain and little to lose by trying it. It was asserted that this therapy would be a safe way of allowing patients to appreciate (or fully live) their last moments.

Barriers and concerns

The eventual implementation of psilocybin-assisted therapy generates many concerns, and certain elements that could hinder its acceptability were raised during the discussions. Participants spoke of the scope of the work that still needs to be done and the many issues that could stand in the way of implementation. Cumbersome bureaucracy and resource issues, such as costs and shortage of healthcare personnel, were identified as major barriers to acceptability. Because of its unconventional nature, some consider that the therapy’s implementation would require a radical adaptation of the healthcare system. There was also concern about the considerable amount of work that still needs to be done, considering that time is of the essence in palliative care. Some participants mentioned increasing curiosity about this treatment in the population and feared a ripple effect in care centers should a patient have a positive experience. Some noted that those who need the therapy the most are often excluded. Indeed, a few say it is too early to talk about acceptability. Given the large exclusion criteria found in studies, many clinicians were uncomfortable with the perspective of excluding certain patients, which could cause distress.

Psilocybin-assisted therapy also generates a great deal of fear and questioning; the lack of knowledge and education seems to be a major factor in the acceptability of this therapy in palliative care. Many participants were concerned about negative psychological effects, such as “bad trips” or longer-term sequelae, as well as physical side effects. In some cases, it was unclear from the data collected whether professionals’ lack of knowledge and fears stemmed from a lack of education or a lack of data on safety. Nevertheless, some professionals said they were more open to this therapy following the conference that the physician (JFS) gave at the start of the consultation.

Ethical and professional accountability issues were also raised as possible concerns hindering the therapy’s acceptability among physicians. Participants wanted to ensure that there were more benefits than drawbacks to this therapy and were more cautious during the exchanges. Some warned against negative bias toward psilocybin and pointed out that “traditional” psychotherapy can also generate negative psychological effects. It was mentioned that resistance to this therapy would not come from palliative care professionals but from political, economic, and medical circles.

Professionals stated that guidelines and a safe, supervised context are needed to deal with these uncertainties to enable greater acceptability and promote wider therapy deployment.

Considerations for the deployment of psilocybin-assisted therapy

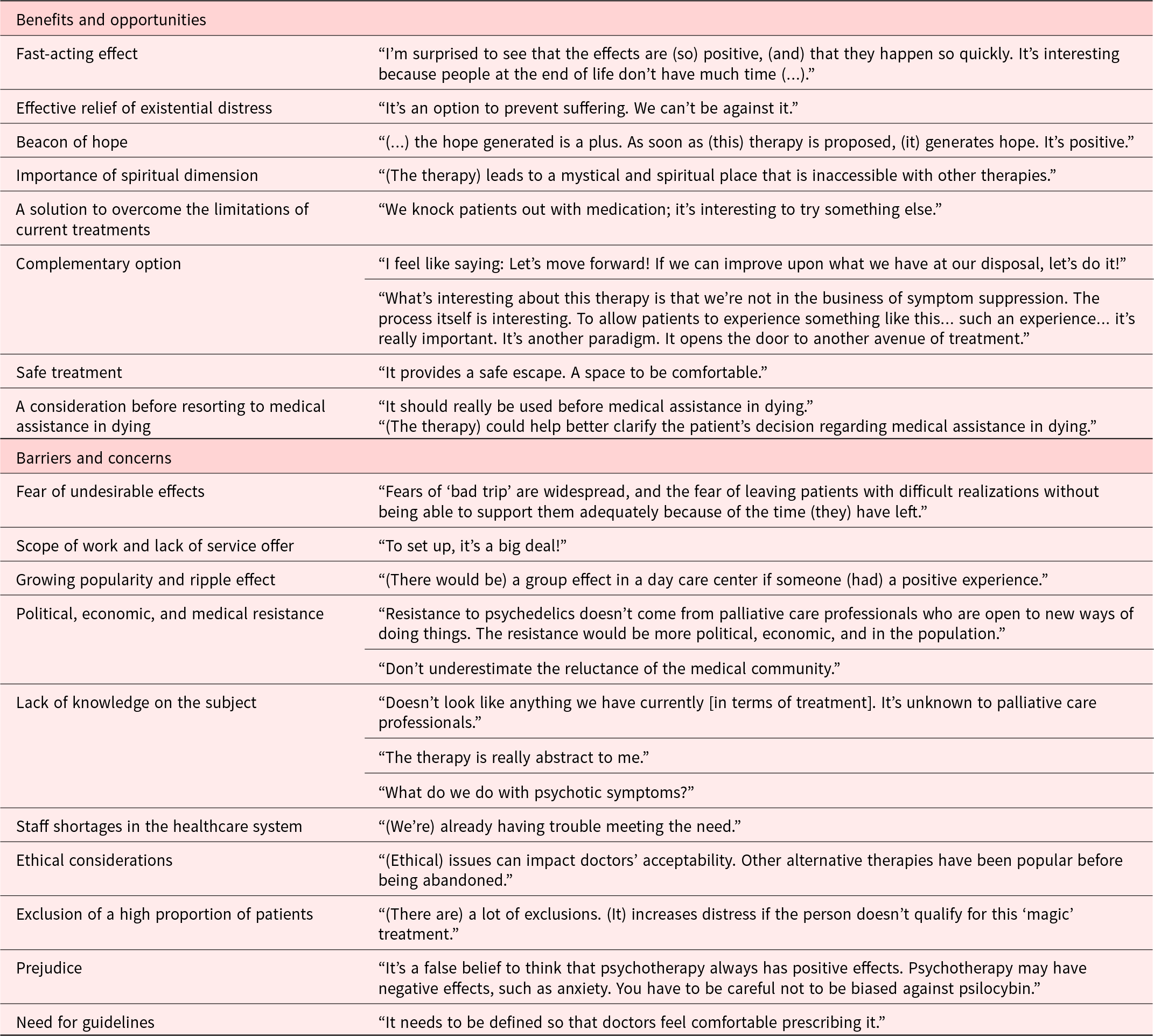

Themes, sub-themes, and the corresponding quotes are listed in Table 3.

Training and education

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes with representative quotes relating to points to consider in promoting the deployment of psilocybin-assisted therapy in palliative care

PAT: psilocybin-assisted therapy

Participants emphasized that many skills are required to accompany people through psilocybin-assisted therapy and that solid, specific training with a component involving clinical experience is needed. It was mentioned that training should not only include prescribers but also palliative care professionals who do not provide the therapy. Several participants reported that they were interested in being educated on the subject. According to some, information on benefits, mechanisms of action, side effects, risks, and drug interactions is needed. Participants also pointed out the need to raise public awareness while not presenting this treatment as “magic therapy.”

Setting

Participants wondered what kind of place would be ideal for the therapy. Some spoke of specialized clinics, possibly palliative day care centers. It was suggested that professionals would be reassured by a hospital setting, unlike patients who dislike the hospital environment. Issues surrounding professional accountability were also raised.

A number of exchanges led to reflections on the types of professionals who could provide this therapy. Some participants argued that since establishing trust was paramount in this therapy, it could open the door to social workers or even volunteers; others questioned this. The latter felt that sound training in psychology was necessary and noted the importance of psychotherapeutic follow-up after this therapy.

Resources

Participants also spoke about the demands of training and treatment costs and the time required for treatment that must be freed up in professionals’ busy schedules, all in the context of health personnel shortages. It was felt that the cost/benefit ratio would have to be established to see whether the investment was worthwhile.

The lack of personnel trained in psilocybin-assisted therapy and the shortage of healthcare staff are two major obstacles that were raised as needing to be addressed to increase access to this therapy, and some mentioned that opening to other types of professionals could reduce costs and pressure on the healthcare system.

Eligibility

There was much discussion centered on the ideal time to receive therapy. According to many, hospice patients are too frail and short of time, and the best time to receive therapy would be in early palliative care. Several participants discussed the importance of clarifying the eligibility criteria for which this therapy is indicated, considering the specificities of palliative care populations.

There seems to be confusion about the very concept of existential distress. Some professionals stated that there are no validated measures to assess it and that it is necessary to define it better. Some question whether there is a real need to treat it, while others argue that psilocybin-assisted therapy should not be considered until all other conventional treatments have been tried. Others questioned when and how psilocybin-assisted therapy could be integrated into the palliative care trajectory.

Participants also asserted the need to simplify administrative and legal processes and consider regional equity to promote access to therapy. Regional disparities in healthcare were deplored, and participants called for this therapy to be accessible outside major centers.

Research

Intensified research to increase the evidence base and better understand drug–drug interactions seems unavoidable to many. They recommended research with broader inclusion criteria and argued that it would be too early to expand access to psilocybin-assisted therapy at this time.

Others questioned the reluctance of professionals. It was mentioned that large studies in palliative care are nonexistent and that many drugs are used without any real demonstrated benefit. The question was raised as to whether some professionals’ demand for more data might be due in part to prejudice against psilocybin-assisted therapy.

Personal autonomy

Several participants agreed on the importance of considering patients’ preferences and pace. Others added that it is sometimes difficult to reconcile patients’ wishes with the practitioner’s desire to provide the best possible treatment based on scientific evidence.

Discussion

This study was carried out in a context where psilocybin-assisted therapy is currently available in an universal healthcare system, so it provides a better understanding of the acceptability of this treatment for the relief of existential distress among palliative care professionals and identifies the needs to facilitate wider access.

Our results show that most professionals considered psilocybin-assisted therapy to be promising. The expressions of interest mentioned during our consultation echo other recent qualitative studies of palliative care professionals (Beaussant et al. Reference Beaussant, Sanders and Sager2020, Reference Beaussant, Tulsky and Guérin2021; Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Akroyd and Sundram2021). In general, professionals seem to recognize the benefits of this therapy and consider that it has the potential to fill a need among people with serious illnesses suffering from existential distress. In addition, the role of psilocybin-assisted therapy in a context where the use of MAID is expanding was discussed. This last-resort treatment is generating complex ethical debates in several countries, including Canada (Mroz et al. Reference Mroz, Dierickx and Deliens2020). This reality is part of the participants’ clinical landscape. The fact that they see psilocybin-assisted therapy as potentially being an option to consider before MAID or being able to clarify the decision of patients considering it invites the palliative care community to reflect on the issue as some authors have done (Berens and Kim Reference Berens and Kim2022; Byock Reference Byock2018; Kratina et al. Reference Kratina, Lo and Strike2023; Strauss Reference Strauss2017). The rapid expansion of MAID and the definitive nature of this care could encourage clinicians to consider psilocybin-assisted therapy as a desirable option or something to consider before MAID (Kratina et al. Reference Kratina, Lo and Strike2023).

Despite this openness toward the therapy, some participants expressed concerns and identified barriers that may limit its acceptability and wider deployment. Other studies of psychedelic therapies carried out among healthcare professionals also reported this mixed stance (Beaussant et al. Reference Beaussant, Sanders and Sager2020; Mayer et al. Reference Mayer, LeBaron and Acquaviva2022; Page et al. Reference Page, Rehman and Syed2021; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Akroyd and Sundram2021, Reference Reynolds, Barnett and Weleff2022). Findings reveal fears about the physical and psychological risks of this therapy. Yet psilocybin is considered a particularly safe substance when administered in a supervised setting (Byock Reference Byock2018; Nichols Reference Nichols2016), and no serious adverse events have been reported among people with terminal illnesses (Maia et al. Reference Maia, Beaussant and Garcia2022; Reiche et al. Reference Reiche, Hermle and Gutwinski2018). Several exchanges raised concerns about possible persistent psychological side effects after treatment, which the literature seems to refute (Carbonaro et al. Reference Carbonaro, Bradstreet and Barrett2016) but also underscores the need for larger studies. Such fears reflect the fact that psychedelic substances are associated with persistent stigmas, and these may interfere with the acceptance of this type of therapy in palliative care (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Agin-Liebes and España2022). The fears might also originate from the anxiety of healthcare professionals around holding responsibility for a treatment they do not feel well educated about.

Our results show that participants lack knowledge about psilocybin-assisted therapy and are calling for more education and research, as raised in other studies of healthcare professionals (Li et al. Reference Li, Fong and Hagen2023; Page et al. Reference Page, Rehman and Syed2021; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Sun and Nava2023). It was not always clear whether this perceived unfamiliarity referred to a lack of knowledge about the effect of psilocybin-assisted therapy and how it works, a lack of familiarity with recent research data, or real unmet research needs. This being the case, knowledge of psychedelic therapies correlates positively with an attitude of openness (Li et al. Reference Li, Fong and Hagen2023; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Barnett and Weleff2022; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Sun and Nava2023). Indeed, some participants claimed that the information they received at the World Café increased their acceptance of this therapy. The educational needs of various palliative care professionals could be met by providing access to existing information, which could be enhanced with more research.

Several studies have reported that various healthcare professionals favor further research (Beaussant et al. Reference Beaussant, Tulsky and Guérin2021; Li et al. Reference Li, Fong and Hagen2023; Page et al. Reference Page, Rehman and Syed2021). According to participants, such additional research is needed to broaden the inclusion criteria for this therapy and define the target population more clearly, as stipulated in Niles, 2021. Still, according to Niles 2021, it seemed unclear to clinicians whether psilocybin-assisted therapy should be administered early in the course of the illness or when the person is in hospice care. On the other hand, participants agreed that this therapy should not be given late in the trajectory when the patient is frail and short of time. Some participants also mentioned that people should receive therapy only after they have tried conventional treatments to relieve existential distress. At present, the characteristics of patients suffering from refractory existential distress may be similar to those deemed too fragile to receive therapy (Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021). Patients with serious illnesses such as cancer are vulnerable and have complex medical histories, which can make it difficult to introduce psychedelic therapies (Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Akroyd and Sundram2021). More research with less restrictive criteria concerning comorbidities, drug interactions, and clarifications surrounding existential distress will be necessary to widen the window of access to treatment. Participants also mentioned that the patient must participate in the decision-making process concerning the care they can receive (Kuosmanen et al. Reference Kuosmanen, Hupli and Ahtiluoto2021). Results show that the embryonic nature of the therapy’s implementation prevents healthcare professionals from fully embracing this therapy and its eventual deployment. Moreover, the absence of a solid framework and guidelines shows uncertainty and confusion among care providers, preventing them from making clear decisions. Other studies have reached the same conclusion (Mayer et al. Reference Mayer, LeBaron and Acquaviva2022; Niles et al. Reference Niles, Fogg and Kelmendi2021; Page et al. Reference Page, Rehman and Syed2021). Participants mentioned that the work required to overcome this impasse is significant and multidimensional, and legal approvals are needed. According to Kratina et al. (Reference Kratina, Lo and Strike2023), there is no specific approach to implementing this therapy in Canada. Thus, legislative changes and stakeholder consultations should be prioritized. Canadian and Australian studies recommend the establishment of consultative bodies to guide the policy and implementation of psilocybin therapy (Rochester et al. Reference Rochester, Vallely and Grof2022; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Korevaar and Harvey2021).

Participants were also concerned that this therapy would increase pressure on resources such as time, cost, and personnel. The shortage of physical and mental healthcare providers in Canada and globally has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and represents a major challenge for healthcare systems and is likely to have an impact on the deployment of psilocybin-assisted therapy (Azzopardi-Muscat et al. Reference Azzopardi-Muscat, Zapata and Kluge2023; Carolyn Reference Carolyn2023; Cummings et al. Reference Cummings, Zhang and Gandré2023; Kuriakose Reference Kuriakose2020; The Lancet Global Health Reference Lancet Global Health2023; Satiani et al. Reference Satiani, Niedermier and Satiani2018; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Korevaar and Harvey2021). One participant pointed out that it was ethically difficult to envisage mobilizing two therapists for one person in the context of resource shortages. Inequalities in access to high-quality palliative care already exist, and some authors worry that implementing this therapy will accentuate current inequities by diverting resources from existing programs (Rosenbaum et al. Reference Rosenbaum, Hales and Buchman2023). Participants also lamented that vulnerable people who would benefit most from this treatment are often excluded. The pressure on already limited resources led some participants to suggest relaxing the selection criteria for assisting professionals. While some mentioned the importance of having professionals trained and qualified to deliver psilocybin-assisted therapy, others argued that they would not necessarily have to be registered psychotherapists or physicians. Some studies agree, stating that Canada might consider opening certification programs to professionals who do not necessarily have a regulated clinical designation (Kratina et al. Reference Kratina, Lo and Strike2023). For instance, the Oregon model envisions the assisting therapist as a new type of professional (Marks and Cohen Reference Marks and Cohen2021). In addition, studies of psilocybin administration in a group setting are underway (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Agrawal and Griffiths2022). This could offer advantages in reducing pressure on resources and increasing access to therapy. However, some participants and authors have raised ethical concerns about vulnerable people who might try psychedelic therapies and the risks this may represent (Villiger and Trachsel Reference Villiger and Trachsel2023). In the literature, the type of professional recommended to provide therapy is based on the model used in research (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Richards and Griffiths2008; Phelps Reference Phelps2017; Smith and Appelbaum Reference Smith and Appelbaum2022). In any case, resource limitations will have to be taken into account when considering the type of therapist who can provide this therapy. Solutions to this major problem must be flexible and adapted to the environment while remaining safe. The growing popularity of psychedelic therapies is leading many people to use these substances on their own outside the legal framework (Pilecki et al. Reference Pilecki, Luoma and Bathje2021). To meet the growing demand for psilocybin-assisted therapy, the training of professionals will need to accelerate (Mocanu et al. Reference Mocanu, Mackay and Christie2022).

Strengths and limitations

The World Café study design brought together various palliative care professionals to discuss psilocybin-assisted therapy freely in a welcoming and nonjudgmental setting, allowing rich insights to emerge. Participants switched tables after each discussion round, avoiding power inequalities and evening out group imbalances and unequal contributions (Löhr et al. Reference Löhr, Weinhardt and Sieber2020). Moreover, assigning table hosts ensured good group dynamics and discussions remained on topic. However, some limitations need to be considered. First, participants’ opinions may not necessarily be generalizable outside the context of the Canadian healthcare system. In addition, purposive sampling may have led to selection bias. Second, while note-takers were assigned to document the discussions, we did not have audio recordings, therefore, some field notes were difficult to interpret. We attempted to mitigate inaccuracies and lack of precision by validating the content with participants, hosts, and note-takers. Third, we cannot confirm that data saturation was reached in this World Café, although participants raised very few new ideas by the end of the second round. Moreover, participants were given the opportunity to add more ideas by discussing the findings in a large group exchange after both discussion rounds, and no new themes emerged at that point. Fourth, the fact that only one coder analyzed and coded all the data may be considered a limitation. However, given the high level of intercoder agreement on a portion of the data, it is unlikely that our main conclusions would have been significantly different with complete double coding of the data. Finally, although we tried to provide a setting conducive to free-flowing exchanges, we cannot discount social desirability bias. However, this bias may be minimal if present since our findings suggest nuanced discussions.

Conclusion

Although palliative care professionals consider psilocybin-assisted therapy as a promising treatment to alleviate existential distress, they shared several concerns and identified a number of obstacles to acceptability and access. Guidelines for implementing psilocybin-assisted therapy must consider training and education of professionals, therapy setting and logistics, resource availability, clarification of eligibility criteria, more research, and respect for individual autonomy.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org10.1017/S1478951524001494.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research staff from the CHU de Québec–Université Laval Research Center and the Institut de soins palliatifs et de fin de vie Michel-Sarrazin–Université Laval and members of the P3A team who participated in the data collection process: François Arès, Amina Belcaïd, Laurence Lambert-Côté, Philippe Houde, Elisabeth Sauvageau, Isabelle Théberge, and Annie Turgeon. They also thank the World Café participants and Université Laval for hosting the event. Other members of the P3A team include Marion Barrault-Couchouron, Gabriel Bélanger, Robert Foxman, Pierre Gagnon, Nicolas Garel, Yann Joly, Florence Moureaux, Olivia Nguyen, and Diane Tapp.

Author contributions

MMG and SLC contributed equally to this work and are co-first authors.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec (AUDACE program). MMG, LP, and AB received graduate student scholarships from the Fonds d’Enseignement et de Recherche (Faculty of Pharmacy, Université Laval).

Competing interests

Houman Farzin and Jean-François Stephan are trainers for the nonprofit organization TheraPsil. Houman Farzin was the Montréal site physician for MAPPUSX, a Phase 3 clinical trial of MDMA-AT for PTSD sponsored by MAPS, and is an early investor in Beckley Psytech. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

The research team ensured that it received written consent from participants before attending the World Café. All participating research team members (table hosts and note-takers) signed confidentiality agreements. The project was approved by the CHU de Québec-Université Laval Research Center ethics committee (2023–6697). Data were collected anonymously to be used only for this research. Results were processed globally, and no participant can be identified or recognized. All participants received monetary compensation for their time ($50 CAD).