Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent type of cancer globally (WHO 2021). The incidence of breast cancer is increasing, and it is also ranked as the most prevalent female cancer in Taiwan (Taiwan Cancer Registry 2014). A woman’s chance of developing invasive breast cancer in her lifetime is about 1 in 8 (12%). However, women with a family history of breast cancer have a significantly higher risk of breast cancer than those without such a family history (American Cancer Society [ACS] 2019). In cases of those having a first-degree relative with breast cancer, the incidence of breast cancer is 2–3 times higher compared to those without a first-degree relative with breast cancer (Brewer et al. Reference Brewer, Jones and Schoemaker2017; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Zakher and Cantor2012). Therefore, if a mother has had breast cancer, her adult daughters should be concerned about getting breast cancer. This may affect her physical and mental health, and she may require support and information from health-care professionals (Chalmers et al. Reference Chalmers, Luker and Leinster2001; Fang et al. Reference Fang, Wang and Lee2022).

Several care needs of women with a family history of breast cancer were identified using an instrument (the Information and Support Needs Questionnaire: ISNQ) developed for women with primary relatives with breast cancer in previous studies (Aloweni et al. Reference Aloweni, Nagalingam and Yong2019; Andic and Karayurt Reference Andic and Karayurt2012; Chalmers et al. Reference Chalmers, Marles and Tataryn2003; Tokkaya and Karayurt Reference Tokkaya and Karayurt2010). These care needs included information needs such as cancer risk for themselves, healthier behavior that could reduce the risk of cancer, self-examination, and general knowledge about breast cancer. Other care needs related to support included support to help deal with worries about their relatives, worries about getting breast cancer, and reminders of the need for regular screening. This instrument was used and initially validated in Canada, Israel, Singapore, and Turkey and revealed that the importance of information needs was beyond that of support needs (Aloweni et al. Reference Aloweni, Nagalingam and Yong2019; Andic and Karayurt Reference Andic and Karayurt2012; Chalmers et al. Reference Chalmers, Marles and Tataryn2003; Tokkaya and Karayurt Reference Tokkaya and Karayurt2010). In addition, learning how to discuss the possibility of getting cancer and the risk of cancer was regarded as very important but was reported to be unmet needs by women with breast cancer in their families.

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer clinics providing cancer-related counseling for high-risk subjects with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer have been established in Western countries. Although several hospitals in Taiwan provide genetic testing and counseling services, most hospitals have no regular cancer risk assessment and cancer-specific counseling channels for groups at high risk for breast cancer who have a family history. As a result, limited information is available to identify hereditary breast cancer in the affected mothers, and relatively few women have received genetic testing. The ISNQ was developed 20 years ago, was used in a Western culture, and was used almost exclusively among women who were receiving regular follow-up visits in high-risk outpatient clinics. Thus, this study was aimed at examining the revised ISNQ and validating it in a community population in Taiwan comprising unaffected daughters of mothers with breast cancer. Since distress, cancer worry, and cancer experience have been demonstrated to be associated with risk perception (Cicero et al. Reference Cicero, De Luca and Dorangricchia2017) and may contribute to various unmet care needs, the objectives of this study were as follows: (1) content validity determined by experts in breast cancer care, (2) criteria validity determined by understanding the relationship between the ISNQ and distress or cancer worry, (3) known-group validity determined by comparing the differences in the ISNQ results based on age and cancer experience, and (4) internal consistency demonstrated using Cronbach’s α.

Methods

Two separate projects were conducted to validate the ISNQ in this study in which 102 participants were from Project 1, and 118 participants were from Project 2. We used 3 phases to thoroughly validate the ISNQ Chinese version (ISNQ-C). First, we translated the ISNQ using a standard procedure and modified it based on our previous qualitative study to ensure cultural adaptation. We also added some items based on the qualitative study (Fang Reference Fang, Wang and Lee2022). Second, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to explore the factor structure and known-group validity of the ISNQ-C using samples from both projects (n = 220). The sample size was adequate since the required sample size was 170 participants for 34 items of the ISNQ-C based on the rule that there were at least 3–5 samples for each item (Munro Reference Munro2005). Finally, we tested the criterion validity of the ISNQ-C using a sample from Project 2 (n = 118) since psychological outcomes were only measured in Project 2.

Procedure used for translation and modification

Forward and backward translation

The original version of the ISNQ with 29 items was translated from English into Mandarin using standard forward and backward translation procedures. Two academic nursing professionals who are fluent in both Chinese and English independently forward-translated the ISNQ and produced a reconciled Chinese version after discussion. A third independent professional who is fluent in both languages back-translated the reconciled Chinese version. Finally, the developer of the ISNQ was invited to review the text in the backward translation version. We further considered suggestions raised by the developer and discussed the adequacy and appropriateness of some items with the developer of the ISNQ by mail to confirm the meanings of the items. Only wordings for 2 items were modified to make the meanings more understandable due to cultural differences.

A total of 29 items were preserved from the original ISNQ. Because our previous study revealed that adult daughters prioritized caring for their mothers both physically and psychologically (Fang Reference Fang, Wang and Lee2022), some important concerns reported by our previous qualitative study were not included in the original ISNQ, so we added additional 5 items to broaden the content of the ISNQ as follows: information about personal health insurance, decrease in worries that the mother will die of breast cancer, support to help with the pressure related to taking care of my mother, sharing feelings related to changes in my relationship between my mother and me, and having someone to talk about worries about a negative reaction on the part of my partner if I get cancer. Five nursing experts who were professionals in breast cancer care, including 3 case managers, 1 breast cancer researcher, and 1 breast surgeon, were invited to examine the content validity and duplication of the items. They were asked to evaluate each item according to the importance, the relevance, and cultural adequacy of each item. The CVI (content validity index) was 0.96. An expert meeting composed of the members of the research team studying issues related to breast cancer care suggested that all 5 of these items could be retained for further testing. Five daughters of mothers with breast cancer participated in a pilot test to examine the face validity of the ISNQ-C (i.e., cognitive comprehension, culture issues related to translation, and missed questions). All the items were clear and did not require revision.

Sample

The participants were the biological daughters of women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer. They were recruited through convenience sampling from 2 medical centers by research team members (breast surgeons) and a website advertisement. The breast surgeons invited daughters accompanied by their mothers with breast cancer to outpatient clinics. The daughters could fill out the questionnaire right away if they had time or could leave their contact information and make an appointment when they were available. Other potential participants from the advertisement were registered using a Google form study application to provide their contact information. The researcher then contacted them via telephone to make an appointment for an interview. The inclusion criteria were (1) Mandarin-speaking, (2) aged 20 years or older, and (3) unaffected by breast or other cancers. The exclusion criteria were (1) cognitive dysfunction and (2) a diagnosis of severe psychiatric disease with a limited ability to communicate.

Data collection

Eligible women were approached during their mother’s outpatient clinic visit and were asked to participate in the study at one of 2 medical centers in southern Taiwan. If they had time and willingness to participate in the study, the self-administered questionnaire was immediately given. If they had willingness but limited time to complete the questionnaire, they were asked to provide contact details. Participants registered through the Google form were also requested to provide their contact information. Research assistants subsequently called them to make an appointment when they were available.

Data were collected from June 2018 to February 2021. Prior to data collection, the women were fully informed about the purpose of the study and given the right to refuse participation and uncontested withdrawal. Their confidentiality was also guaranteed. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of 2 teaching hospitals (National Cheng Kung University Hospital and Chi Mei Medical Center) in southern Taiwan for 2 projects (protocol numbers B-ER-107-077, B-ER-109-170, and 10705-001).

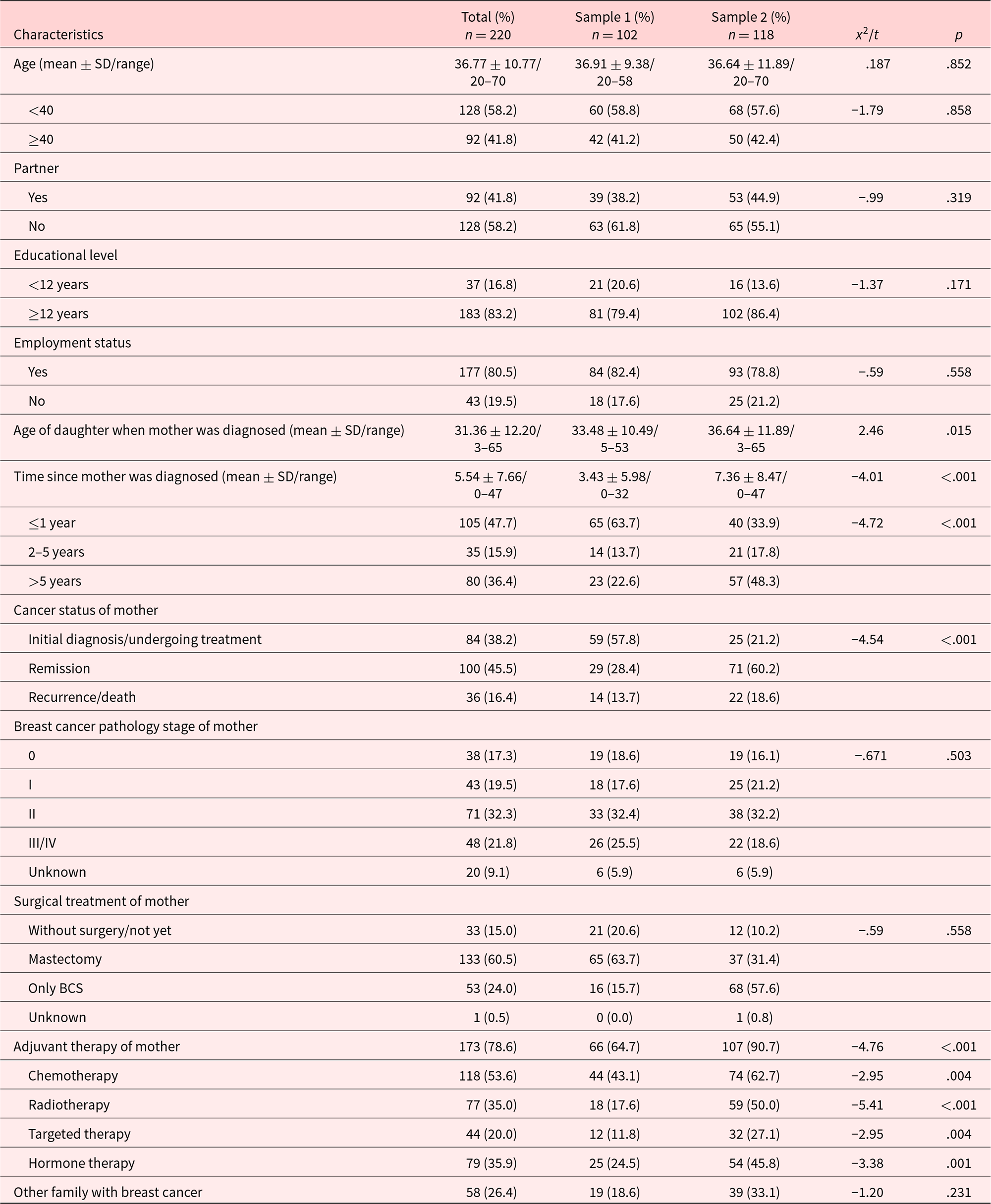

Table 1. Demographic and disease characteristics of Samples 1 and 2

Measures

Information and Support Needs Questionnaire

The original ISNQ consists of 29 items used to measure needs for information and support among women who have a family history of breast cancer (Chalmers et al. Reference Chalmers, Luker and Leinster2001). Here, we focused on women who had mothers with breast cancer. Added items were integrated into the original format and formulated into the ISNQ Chinese version, which had a total of 34 items. Participants were asked to answer whether the needs described in the items were not applicable or were met. The degree to which an item expressed that the need was met was rated as follows: met fully (score 0), met somewhat (score 1), met a little (score 2), or not met at all (score 3). The need items were grouped into 2 domains: information (18 items) and support (11 items). The needs expressed in each domain were added together and divided by the number of items, where a lower score represented a lesser degree of unmet needs (Table 2).

Table 2. Factor loadings of exploratory factor analysis and reliability of sub-dimension of sample 1 & 2

a New added items.

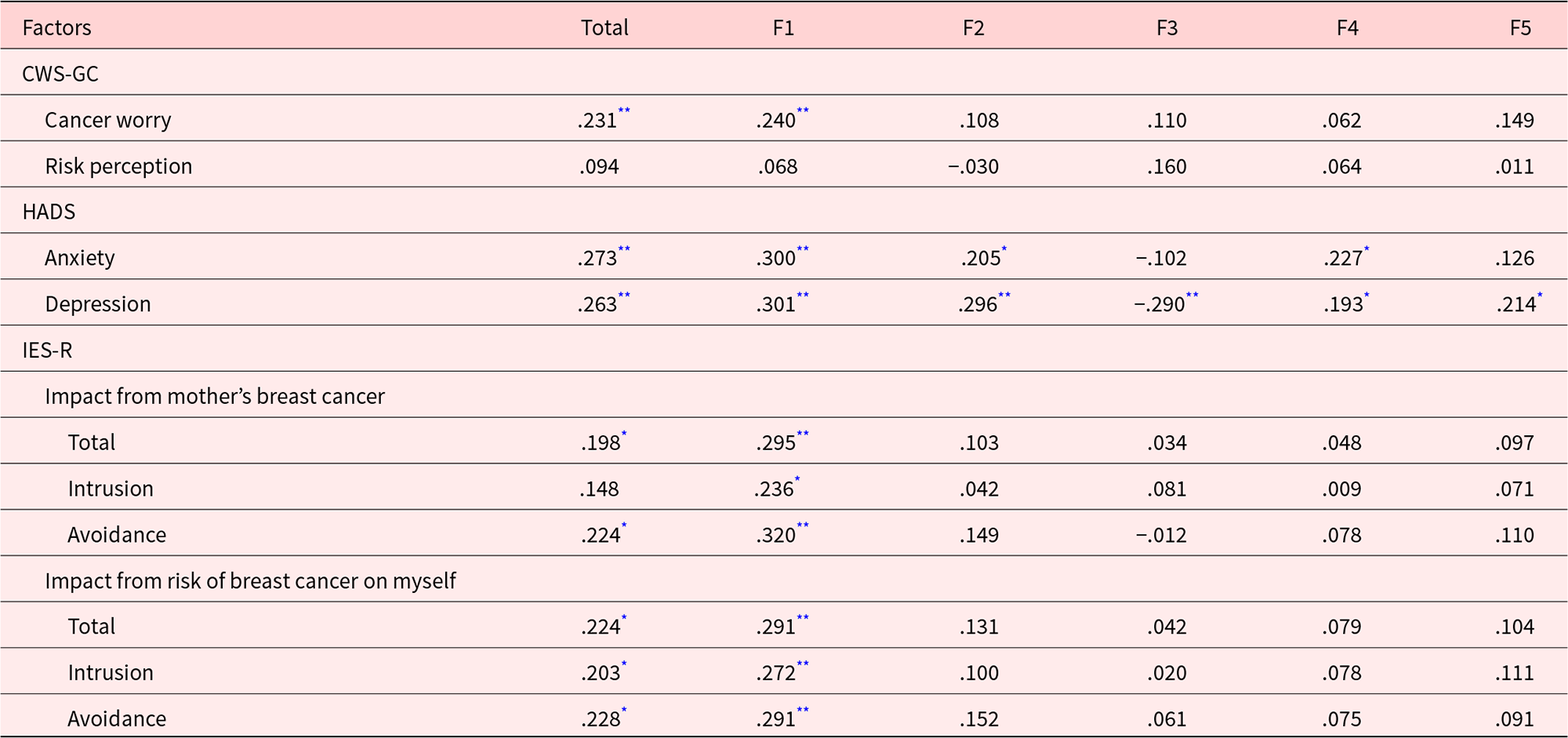

Table 3. Criterion validity of the ISNQ

ISNQ: Information and Support Needs Questionnaire; CWS-GC: Cancer Worry Scale Revised for Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IES-R: Impact of Event Scale – Revised.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) includes 14 items assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression, of which 7 measure anxiety, and 7 measure depression. Likert scores using a 0–3-point scale are used, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. The symptoms expressed in each domain were added together, and cut-off scores were used to categorize anxiety and depressive symptoms, with values of over 8 indicating possible anxiety and depression, and scores of 11 or above indicating the likelihood of anxiety and depression. The English version of the HADS has been used in high-risk breast cancer populations (Ringwald et al. Reference Ringwald, Wochnowski and Bosse2016), and the Chinese version of the scale has been widely used in cancer patients with good reliability and validity for women with breast cancer (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Lin and Kuo2021).

Cancer worry (Cancer Worry Scale revised for Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling)

Cancer worry was measured using the Cancer Worry Scale revised for Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling (CWS-GC) in which cancer worry and risk perception domains are included. The cancer worry domain includes 5 items measuring the intensity of worry about developing breast cancer, anxiety about future mammograms/breast echo, the impact of breast cancer worry on mood, daily functioning, and the frequency of worries about developing breast cancer. It is answered using a 5-point scale (from 0 = not at all/never to 4 = very much/very often). The degree of worry in each item was first added together and divided by the number of items and then rescaled to 0∼100 following the instructions of the developer (Caruso et al. Reference Caruso, Vigna and Gremigni2018). A higher score indicated a higher level of concern about cancer. Two items measured the risk perception domain and included the perceived risk of having an altered breast cancer gene and of developing breast cancer, which were rated using a visual analog scale ranging from no perceived risk (0%) to the highest perceived risk (100%). After obtaining permission to use this scale from the original author, we used a forward and backward translation to formulate the Chinese version. The internal consistency was .89 for the cancer worry domain and .84 for risk the perception domain.

Impact Event Scale-Chinese

The impact of a mother’s breast cancer on an adult daughter was measured using the Impact Event Scale-Chinese (IES-C) with 15 items in which 2 subscales, including intrusion and avoidance psychological reactions, were included (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Lai and Liao2005). Because the impact of a mother’s breast cancer can be divided into the impact of the event of the mother’s breast cancer diagnosis and the impact of the perceived risk of getting cancer, we measured 2 situations to prevent misunderstandings. Responses were scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 5, where 0 = “not at all,” 1 = “rarely,” 3 = “sometimes,” and 5 = “often.” Subscale scores were calculated by adding the respective items, and the total IES score was calculated using the sum of all 15 items (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Lai and Liao2005). A higher score indicated more intrusive feelings of worry and a greater tendency toward avoidance. The internal consistency was .88 for the impact of mother’s breast cancer diagnosis and .89 for the impact of the perceived risk for getting cancer.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Frequency and percentage were used to examine the sociodemographic characteristics of the daughter. Mean and SD were calculated to describe the burden of care, worries associated with getting cancer, the impact of the diagnosis, and the level of depression and anxiety. A chi-squared test and a Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the characteristics between the 2 samples.

Three steps were used to conduct psychometric testing in this study. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first used to explore the ISNQ-C structure among these items. A principal axis factor procedure with a varimax rotation was selected to extract latent constructs since it can be used when the assumption of normality has been violated. Items with factor loadings less than 0.4 were initially deleted. Second, we used the HADS, IES-C, and CWS-GC scores as criteria by which to examine the criterion validity based on the Pearson correlations. We hypothesized that the degree of unmet needs would be positively correlated with the HADS, IES-C, and CWS-GC scores. Finally, known-group validity was tested using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the degree of unmet needs scores between the different health statuses of the mothers in which statuses, including deceased, diagnosed/undergoing treatment, remission, and in relapse treatment, were compared.

Results

Clinical, demographic, and psychosocial characteristics of the sample

In total, 220 questionnaires were completed and analyzed in this study. There were 102 women in Sample 1 and 118 women in Sample 2. The sample size was adequate according to the recommendation of MacCallun, who suggests that at least 100 respondents should be recruited for the purpose of conducting a factor analysis as well as the subject-to-variable ratio rule (Bryant and Yarnold Reference Bryant, Yarnold and Yarnold1995; Fabrigar et al. Reference Fabrigar, Wegener and MacCallum1999; MacCallum et al. Reference MacCallum, Widaman and Zhang1999).

In total, the 220 women ranged in age from 20 to 70 years old (M = 36.67, SD = 10.77), and less than half (92, 41.8%) were partnered. The majority (183, 83.2%) had completed 12 years of education and were employed (177, 80.5%). In addition, the age of the daughter when the mother was diagnosed ranged was from 3 to 65 years old (M = 31.36, SD = 12.20), and nearly half (47.7%) of the daughters’ mothers had been diagnosed with breast cancer less than 1 year priorpt to the study. In terms of the mother’s condition, nearly half (100, 45.5%) of the mothers were in remission, and 11 (5%) of the mothers were deceased. More than half (133, 60.5%) had undergone a mastectomy and received chemotherapy (118, 53.6%) as adjuvant therapy. In terms of the family history, one-fourth (58, 26.4%) of the participants also had other family members diagnosed with breast cancer. There were some differences between Samples 1 and 2 in terms of which daughter was younger in Sample 1 when the mother was diagnosed (p = .015), and more mothers were in remission and had received adjuvant therapy in Sample 2 (p < .0001) (Table 1).

Psychometric properties of the ISNQ-C

Exploratory factor analysis

A factor analysis was conducted on both samples. After deleting 2 items including items 8 and 28 with factor loadings of less than 0.4, the repeated EFA extracted 5 factors that had eigenvalues of >1, which totally explained 58.11% of the variance. The first cluster of 11 items was related to “releasing my anxiety,” the second cluster of 7 items was related to “support for mother,” the third cluster of 8 items reflected a desire to “decrease risk to self,” the fourth cluster of 3 items was related to “support for regular examinations,” and the fifth cluster of 3 items was related to “concerns about children,” and each factor explained 17.64%, 14.23%, 11.88%, 7.38% and 6.99%, respectively (Table 2).

Internal consistency

The overall reliability of the ISNQ-C demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α = .87. The releasing my anxiety, support for mother, decreased risk to self, support for regular examinations, or concerns about children care needs domains were .91, .89, .88, .83, and .86, respectively (Table 2).

Criterion validity of the ISNQ-C

Criterion validity was examined in Sample 2. The Pearson correlations between the degree of unmet needs for the ISNQ-C and cancer worry (r = .23, p < .01), anxiety (r = .27, p < .01), depression (r = .26, p < .01), impact of mother’s breast cancer diagnosis (r = .19, p < .05), and impact of the perceived risk of getting cancer (r = .22, p < .05) were significant. In addition, there were correlations for each cluster, including releasing my anxiety, support for mother, decreased risk to self, support for regular examinations, or concerns about children for the ISNQ-C, HADS, and IES-C (r = .19–.32, p < .01) (Table 3). These findings provided evidence that the ISNQ-C had acceptable criterion validity for measuring the needs of daughters of mothers with breast cancer.

Known-group validity of the ISNQ-C

Known-group validity was examined in Sample 2. The ISNQ-C discriminated between the degree of unmet needs reported by the different subgroups. As a result of the unequal sample size, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. It indicated that the group with a deceased mother reported significantly more unmet needs related to “releasing my anxiety,” “support for my mother,” “decreased risk to self,” and “support for regular examinations” compared to when the mother was stable and was undergoing regular follow-ups (Table 4). The ANOVA test also revealed that the daughters less than 40 years old reported more unmet needs related to “releasing my anxiety” and “support for regular examinations.” In addition, the daughters reported more unmet needs related to “concern for children” in the group of mothers diagnosed over 5 years prior to the study.

Table 4. Known-group validity of the ISNQ

ISNQ: Information and Support Needs Questionnaire.

a Kruskal–Wallis test.

b p < .05 (.038) in comparisons of 2–5 years and >5 years.

c p < .05 (.038) in comparisons of ≤1 year and >5 years.

Discussion

Efficient screening of the needs of the first-degree family of women with breast cancer can help health-care providers develop personalized care plans for these high-risk women. This study provided details about psychometric testing using the ISNQ‐C. Five factors, including releasing my anxiety, support for mother, decreased risk to self, support for regular examinations, and concerns about children’s needs explained 58% of the variance based on the results of the EFA, which demonstrated that this scale is valid. The results of the known‐group comparison, criterion validity, and Cronbach’s α also indicated that the ISNQ-C has acceptable validity and reliability.

Our 5-factor solution was consistent with previous studies, indicating that psychological support and information needs are prevalent among daughters who have mothers with breast cancer. In the “releasing my anxiety” domain, the 5 added items were all retained and grouped into this domain, which covered worries about the mother dying, burden of care, and concerns about insurance. These results were echoed in previous studies. Daughters experienced shock and fear and felt overwhelmed after receiving news of their mothers’ breast cancer diagnosis. They also worried about the possibility of losing their mothers (Raveis and Pretter Reference Raveis and Pretter2005; Wiggs Reference Wiggs2011). A loss of energy and feeling overwhelmed were common reactions of caregivers of women with breast cancer, regardless of whether the caregivers were daughters or mothers. In one study, older mothers caring for daughters with breast cancer were interviewed. It was also found that these mothers worried about their daughters’ survival and experienced uncertainty about the effect of the various treatments (Raveis et al. Reference Raveis, Pretter and Carrero2010). In terms of relationships with partners, since partner support is essential to reducing fear of cancer among women with a high risk of breast cancer (Schroeder et al. Reference Schroeder, Duggleby and Cameron2017), women may be concerned about a partners’ negative opinion about a diagnosis that may impact their relationship.

The other 4 factors addressed in the ISNQ-C were also supported by several studies. In the case of the factor “support for mother,” previous studies have revealed that in addition to expected information about breast cancer and the associated treatments, the daughters also wanted to understand ways to decrease the possibility of cancer recurrence in their mothers (Aloweni et al. Reference Aloweni, Nagalingam and Yong2019; Andic and Karayurt Reference Andic and Karayurt2012; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Lomma and Chih2020). Because the level of perceived support provided to mothers by daughters increased, the reported depression levels decreased (Vodermaier and Stanton Reference Vodermaier and Stanton2012). Health-care professionals may want to provide more information that will help these daughters understand the trajectory of breast cancer in order to provide them with the support necessary to face expectations across all stages of their mother’s disease and treatment. The “decreased risk to self” factor demonstrated that worries about getting cancer were perceived by daughters who were involved in their mothers’ breast cancer. This result echoed the results of previous studies, indicating that women with a family history of breast cancer believe that the probability of getting breast cancer will be over 50% (Quillin et al. Reference Quillin, Bodurtha and McClish2011; Seven et al. Reference Seven, Bağcivan and Akyuz2018). As a result, these daughters wanted more information about the risks of breast cancer, examinations for early detection, and health promotion that would be likely to decrease their risk. Furthermore, they also wanted someone to remind or support them with regular examinations, which reflected the factor “support for regular examinations.” Adult daughters faced with their mothers’ suffering and their perceived fear of their own risk of cancer experienced psychological distress (Fang Reference Fang, Lin and Kuo2021), so they may also desire support or information needs related to releasing their anxiety. In terms of the “concern for children,” since family members may share genetic variations and disease risks, these daughters were also concerned about risks to their children and found it difficult to talk to their children about this issue. Concerns about children were also revealed by a study examining daughters with known BRCA1/2 mutations on their mothers side (Patenaude et al. Reference Patenaude, Tung and Ryan2013). These results were also supported by a previous study that showed the mother–daughter interaction in a family with a risk of breast cancer was challenging due to the mothers’ struggles to elicit their daughters’ concerns even when they were still eager for more information related to genetic counseling and risk of breast cancer (Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Maloney and Glogowski2014).

Criterion validity was supported by a significant correlation between the scores on both the total and individual domains of needs and cancer worry, anxiety, and depression, and the impact of the mother’s breast cancer diagnosis, especially for the “releasing my anxiety” domain. This finding was congruent with the findings of a previous study among breast cancer survivors in which unmet needs were found to be a predictor of women’s psychological well-being (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Cheng and Lin2018). It is interesting that daughters who had higher needs related to “decreased risk to self” exhibited fewer depressive symptoms. Since information provided by health-care professionals can help women at high risk for cancer understand their situation and in turn reduce their uncertainty related to getting breast cancer (Dean and Davidson Reference Dean and Davidson2018), this finding can be explained by the fact that knowing which information they need related to preventing or detecting breast cancer may indicate that these daughters have already learned how to control their degree of risk, which in turn reduced uncertainty and decreased depression. This can be explored further in the future.

Known-group validity was supported by the difference between the status of mothers in which the needs to “release anxiety,” gain “support for mother,” “decrease risk to self,” and obtain “support for regular examinations” were greater in the group where the mother had died. The daughters’ emotions were influenced by witnessing the suffering and the illness trajectory of their mothers (Chalmers and Thomson Reference Chalmers and Thomson1996). When women at high risk for breast cancer experience the death of a relative, they may suffer emotional trauma for a long period of time (Underhill et al. Reference Underhill, Lally and Kiviniemi2012). This serves as a reminder to health-care professionals to pay attention to the needs of women whose mothers have died. Known-group validity was also supported by the age of the daughters, where younger women experienced more unmet needs. Since taking care of mothers is a responsibility for daughters in Chinese culture (Fang Reference Fang, Wang and Lee2022), younger daughters with underage children to raise may acquire more support. Furthermore, as a result that the cancer treatment may be completed within a year after diagnosis, the daughters’ unmet needs about “concern for children” could arise 5 years after their mothers’ diagnosis.

Strengths and limitations

A standard translation was used for the ISNQ-C validation. Considering cultural differences along with changes over time would be useful in clinical practice to support women with a family history of breast cancer. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, only female participants were recruited, so these results may not be generalizable to men at risk for breast cancer. Second, even though we examined the structure of the ISNQ-C using an EFA, it is suggested that the sample size be increased, and a CFA (confirmatory factor analysis) be used to confirm the structure in the future. Third, even though the criterion validity examined using a Pearson correlation was significant, the r value of the correlation was not high, which may have been due to the fact that all participants did not know their mutation status. Fourth, we did not examine the test–retest reliability of the ISNQ‐C. Therefore, its reproducibility may be questioned. Finally, assessing the prevalence of ovary cancer or other types of cancer would be useful to understand the risk to this population.

Implications for practice

This study validates the ISNQ‐C for use among women in Taiwan with a family history of breast cancer. Given the development of precision medicine and genetic technology, cancer care has been transferred from a focus on treatment to a focus on prevention. As a result, using this assessment tool before genetic counseling to target the individual needs of women at risk for breast cancer would be helpful for counselors or other health-care professionals, so they can provide personalized care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants in this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.