Introduction

Palliative care (PC) is an approach focused on improving the quality of life (QoL) through the reduction of suffering, the management of psychological and physical symptoms in cancer patients, and providing comprehensive support to caregivers (Bakitas et al. Reference Bakitas, Lyons and Hegel2009; Patil et al. Reference Patil, Singhai and Noronha2021). While PC has proven beneficial at any cancer stage, its advantages are more pronounced when initiated at the disease’s diagnosis (Crawford et al. Reference Crawford, Dzierżanowski and Hauser2021; Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Aapro and Kaasa2018). Nonetheless, PC in cancer is often introduced after unsuccessful oncological treatments (Seow et al. Reference Seow, Barbera and McGrail2022). In recent years, early PC (EPC) has demonstrated its potential in guiding treatments from diagnosis to end of life (EoL), considering patient preferences and notably reducing futile life-sustaining interventions (Haun et al. Reference Haun, Estel and Rücker2017; Šarić et al. Reference Šarić, Prkić and Jukić2017), while enhancing patients’ and caregivers’ QoL (McDonald et al. Reference McDonald, Swami and Hannon2017).

In cancer patients, the main international associations recommend offering PC in the early stages of the disease (Blum et al. Reference Blum, Seiler and Schmidt2021; Ferrell et al. Reference Ferrell, Temel and Temin2017; Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Swami and Krzyzanowska2014), and this has resulted in a significant decrease in hospitalizations in acute settings such as the intensive care unit (ICU) or the emergency department (ED) (Crawford et al. Reference Crawford, Dzierżanowski and Hauser2021). In this regard, it has been reported that among the 80% of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer who pass away in a hospital setting, approximately 57% of them die in an acute care setting (Philip et al. Reference Philip, Le Gautier and Collins2021). Admissions to the ED and ICU may occur due to insufficient attention to home symptoms or limited access to PC services (Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Earle and Rangrej2015). Other futile EoL interventions associated with acute hospitalizations that can potentially impact the QoL of patients and their caregivers are the requirement of surgery, chemotherapy (ChT), radiotherapy (RT) (Adam et al. Reference Adam, Hug and Bosshard2014; Crawford et al. Reference Crawford, Dzierżanowski and Hauser2021), antibiotic therapy (ABT) (Stiel et al. Reference Stiel, Krumm and Pestinger2012), and blood transfusions in the last 30 days of life (Preston et al. Reference Preston, Hurlow and Brine2012).

Studies have reported that late initiation of PC (LPC) significantly increases the likelihood of cancer patients receiving aggressive interventions at the EoL (Morita et al. Reference Morita, Akechi and Ikenaga2005; Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Riechelmann and Krzyzanowska2008). However, there is currently no consensus on the specific time to consider EPC. A time ranging from 8 to 12 weeks before death has been proposed (Robbins et al. Reference Robbins, Hackstadt and Martin2019).

The importance of EPC has been widely described in various clinical settings where access to health services differs from those provided in developing countries such as Mexico. While there is a growing consensus on the benefits of EPC, the specific timing and the extent to which EPC can influence outcomes, including reducing hospitalizations in acute settings like the ICU or ED, have not been fully established in certain health-care contexts. This investigation emphasizes the significance of early initiation of PC services as a crucial factor in reducing unnecessary hospitalizations and EoL interventions. Therefore, in this descriptive cross-sectional study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of admissions to acute hospital settings (ED and ICU) as well as the use of EoL medical interventions among deceased cancer patients who receive EPC or LPC and in those who do not receive interventions by the PC team.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study from a single center, which included adult cancer patients who died during their hospital stay at the National Cancer Institute (INCan) in Mexico City, which is a tertiary care hospital. INCan is a leading institution in Mexico for cancer care and treatment. It boasts state-of-the-art hospital facilities with a total of 188 beds dedicated to oncology patients. Annually, INCan records a significant number of admissions, attending approximately 7300 patients diagnosed with various types of cancer. Situated in Mexico City, INCan serves as a major health-care institution that attends patients from diverse regions and states across the country. These data reflect the magnitude of INCan’s commitment in the fight against cancer and its dedication to providing comprehensive and specialized care to patients facing this devastating disease.

This research was carried out in accordance with the statutes of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (Cuschieri Reference Cuschieri2019) and was approved by the INCan research committee under number 2022/090.

Demographic and clinical variables

The institutional electronic clinical records were used to identify all patients over 18 years of age who died between January 2018 and June 2022 and from which sociodemographic data such as gender, age, marital status, maximum level of scholarship, and monthly income were obtained. We excluded all hospitalized patients and deaths due to complications from COVID-19, as well as patients with more than 365 days of follow-up before death.

Data such as the cancer type at the time of diagnosis, the occurrence of metastases, and the number of metastatic sites were obtained through a review of each patient’s clinical records. Furthermore, data on admission to the ED and ICU in the last 6 months of life, as well as medical interventions offered at the EoL (surgery, ChT, RT, ABT, and blood transfusions), were collected.

Determination of study groups

Our main variable of interest was the time from the start of the PC to death, and the patients were classified into 3 study groups. Those receiving PC for over 90 days before death were assigned to the EPC group, while those admitted to the PC department for 90 days or less before death were assigned to the LPC group, and finally, those patients who were not referred to the PC service during their illness were assigned to the non-PC (NPC) group. Regarding the EPC group, this interval was considered as the cutoff point since this is the time considered to obtain the maximum benefits offered by the PC. This cutoff point has been used in previous studies (Michael et al. Reference Michael, Beale and O’Callaghan2019; Rozman et al. Reference Rozman, Campolina and López2018).

Admission to acute hospital settings and medical interventions at the EoL

Our analysis focused primarily on determining the prevalence of ICU and ED admissions in the last 6 months of life for the study groups. For this, these variables were defined as at least 1 admission to the ICU or ED in the last 6 months of life. Additionally, we determined the prevalence of medical interventions such as ChT, RT, blood transfusions, and ABT in the last 30 and 14 days of life. Regarding surgeries, we considered these in the last 6 months of life, as has also been previously reported (Lopez Acevedo et al. Reference Lopez Acevedo, Sandoval and Lee2013). All the above variables were defined as dichotomous variables.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation or medians and interquartile range (IQR), depending on the normality test. The distribution of the variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and graphical methods. Variables were compared using the χ 2 or Fisher’s test for qualitative variables and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal–Wallis for quantitative ones. No data imputations were performed. All statistical tests were performed in R software version 4.2.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing). P value < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

Results

A total of 1762 patients were included in the analysis, with a mean age of 56.1 ± 16.3 years. Of these, 56.8% (n = 1000) were women, 40.2% were married (n = 709), and 24.1% (n = 425) had completed primary school as their highest level of education (Table 1). The monthly income of all the patients evaluated was $275.0 USD (IQR $176.0–$440.0 USD). Significant differences were found in sociodemographic variables among the groups, except for age, marital status, and monthly income.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with cancer

Data presented as mean ± SD, median (IQR), frequency, and percentages, as appropriate.

EPC = early palliative care; LPC = late palliative care; NPC = non-palliative care.

a χ 2 or Fisher’s exact test.

b ANOVA test.

c Kruskal–Wallis test.

* A change in exchange rate of 1 USD = 18.18 MXP was considered, dated April 12, 2023, taking as reference the BANXICO data https://www.banxico.org.mx/tipcamb/main.do?page=tip&idioma=sp.

Regardless of time, 45.2% (n = 796/1762) of the patients who received PC, only 12.3% of these were consulted early (n = 98/796). Of the patients who received PC, the median days of PC onset before death were 5 days (IQR: 2.0–31.5) during the last hospitalization. The onset of PC occurred with a median of 4 days before death (IQR: 2–13) for the LPC group and 177.5 days (IQR: 137–226) for the EPC group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Raincloud plot of the days prior to death between the EPC and LPC groups. EPC: early palliative care; LPC: late palliative care; NPC, non-palliative care.

The analysis of the cancer types showed that 21.5% had hematological malignancies, 11.8% had breast cancer, and 9.9% had lung cancer. About 46.1% of the patients had a diagnosis of stage IV cancer, with the majority belonging to the EPC group (61.2%). In 11.1% of all cases, metastasis was found in 2 or more sites, with a higher prevalence in the EPC group (21.4%) (Table 1).

Overall, patients who received EPC showed a lower proportion of ICU and ED admissions, as well as a reduced utilization of ChT, RT, ABT, blood transfusions, and surgery compared to those who received LPC or never received PC (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of the application of medical treatments in the last 14 days of life by study group. EPC: early palliative care; LPC: late palliative care; NPC, non-palliative care.

In relation to medical interventions within the last 14 days of life, the EPC group exhibited a lower frequency when compared to both the LPC and NPC groups, except for RT, where the incidence was higher in the LPC group (3.7%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of the frequency of medical interventions at the end of life according to the moment of initiation or not of PC. EPC: early palliative care; LPC: late palliative care; NPC, non-palliative care.

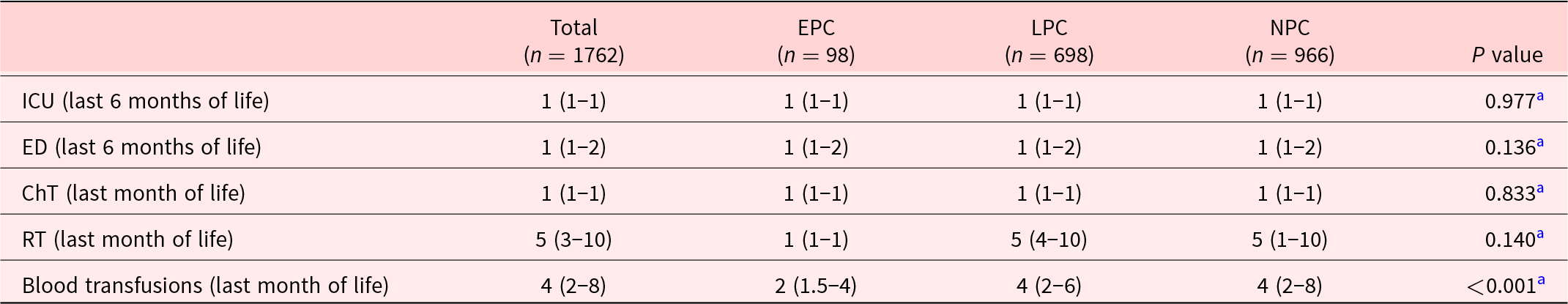

Regarding the number of treatments provided, we only found a significant difference in the number of blood transfusions, which was higher in the NPC group (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of admissions to acute hospital settings and end-of-life medical interventions in cancer patients

Data presented as median (IQR).

EPC = early palliative care; LPC = late palliative care; NPC = non-palliative care; ICU = intensive care unit; ED = emergency department; ChT = chemotherapy; RT = radiotherapy.

a Kruskal–Wallis test.

Discussion

The study’s findings show that patients who received EPC experienced fewer admissions to the ICU and ED. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in the use of ChT, RT, ABT, blood transfusions, and surgeries among these patients when compared to those who received LPC or NPC. These findings suggest that the EPC may have a positive impact on reducing invasive medical interventions and on the appropriate management of patients in advanced or terminal situations.

About 45.2% of patients received care from the PC team, with a median time from PC initiation to death of 5 days (IQR: 2–31.5). However, only 12.3% received EPC. Previous reports from Mexico indicate that only 29.8% of patients with advanced solid cancer are referred to PC (Alcalde-Castro et al. Reference Alcalde-Castro, Soto-perez-de-celis and Covarrubias-Gómez2020). Similarly, a retrospective study at our center found that 28.4% of critically ill cancer patients received PC before ICU admission, with a median time of 3 days (IQR: 2–22) between the first PC intervention and death (Ñamendys-Silva et al. Reference Ñamendys-Silva, López-Zamora and Córdova-Sánchez2021). This prompts a thought-provoking discussion on the need to delve deeper into study results nuances. While categorizing patients into EPC, LPC, and NPC groups initially suggests distinct access levels to PC interventions, a closer examination reveals blurred lines between LPC and NPC groups. This implies that the differences in access might not be as pronounced as they appeared. In essence, the study’s design might not fully capture the true disparity between the 3 groups, especially considering the limited timeframe of PC implementation in the LPC subgroup.

This study highlights the significant reduction in admissions to acute hospital settings, such as the ED and ICU, in the last 6 months of life with the early integration of PC. Our findings align with previous research, demonstrating that patients who received LPC were more likely to be admitted to the ICU in the last months of life (OR: 3.1; 95% CI: 1.81–5.21) (Romano et al. Reference Romano, Gade and Nielsen2017). Reducing acute hospitalizations remains crucial to improving the QoL for patients with advanced cancer (Romano et al. Reference Romano, Gade and Nielsen2017).

Surgical procedures are crucial in the treatment of cancer, especially for early-detected solid tumors. In some cases of advanced cancer, surgery may be part of PC treatment (Al-Mahrezi and Al-Mandhari Reference Al-Mahrezi and Al-Mandhari2016; Deo et al. Reference Deo, Kumar and Rajendra2021). Approximately, 20% of U.S. patients who died in 2008 underwent surgery in their last year of life (Kwok et al. Reference Kwok, Semel and Lipsitz2011). However, only 4%–38% of high-risk surgery patients receive PC services before death (Heller et al. Reference Heller, Jean and Chiu2019; Olmsted et al. Reference Olmsted, Johnson and Kaboli2014; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Harris and Peck2017). Our study revealed that surgeries were more common in the NPC and LPC groups than in the EPC group. This variation may stem from the careful consideration of surgery’s potential risks and benefits by both patients and medical teams. The integration of PC requires a comprehensive assessment of surgical procedures, providing essential decision-making support (Moroney and Lefkowits Reference Moroney and Lefkowits2019).

Palliative ChT aims to alleviate symptoms and improve QoL rather than provide a cure, but there is often a misconception among patients that it is a curative approach (George et al. Reference George, Prigerson and Epstein2020; Weeks et al. Reference Weeks, Catalano and Cronin2012). Administration of ChT in the last 30 and 14 days has been associated with adverse outcomes, including ED and ICU admissions, mechanical ventilation requirement, and a reduced likelihood of achieving a preferred place of death (Akhlaghi et al. Reference Akhlaghi, Lehto and Torabikhah2020; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Zhang and Keating2014). Guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the European Society for Medical Oncology recommend discontinuing ChT in the last 30 days of life to maintain QoL and reduce costs (Crawford et al. Reference Crawford, Dzierżanowski and Hauser2021; Hui et al. Reference Hui, Didwaniya and Vidal2014). Our study reveals that patients in the EPC group were less likely to receive ChT in the last 30 and 14 days compared to LPC and NPC groups. Other analyses indicate that EPC significantly reduces the chance of receiving ChT in the last 60 days for certain patients (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Pirl and Jackson2012). Regarding RT, its limited benefits for EoL patients make its administration in the last month not recommended (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Singer and Boreta2019). It is emphasized that EPC alongside disease treatments is crucial to managing symptoms induced by RT and maintaining patient QoL (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Singer and Boreta2019).

Anemia affects around 90% of advanced cancer patients undergoing ChT, particularly in cases of lung and gynecological cancers treated with platinum-based therapies (Torres et al. Reference Torres, Rodríguez and Ramos2014; Watkins et al. Reference Watkins, Surowiecka and Mccullough2015). Blood transfusions, while not necessarily improving performance status, can provide temporary QoL benefits, with considerations for potential risks like fluid overload and allergies (Delaney et al. Reference Delaney, Wendel and Bercovitz2016; Preston et al. Reference Preston, Hurlow and Brine2012). Decisions regarding the initiation of blood transfusions consider factors such as anemia symptoms, active bleeding, low hemoglobin levels, and external influences like patient or family preferences (Chin-Yee et al. Reference Chin-Yee, Taylor and Downar2019). Nevertheless, a systematic review conducted by Chin-Yee et al. implies that although transfusions might provide relief from symptoms, the extent of their impact and the associated risks remain uncertain. Consequently, there is insufficient evidence to unequivocally endorse their use in PC (Chin-Yee et al. Reference Chin-Yee, Taylor and Rourke2018).

In our study, 28.6% of patients in the EPC group received at least 1 blood transfusion in the last month of life. Considering the constrained short-term benefits, potential risks, and elevated costs, international guidelines emphasize the significance of selectively offering transfusions based on perceived patient benefit rather than administering them indiscriminately to cancer patients at the EoL with anemia and thrombocytopenia (Aapro et al. Reference Aapro, Beguin and Bokemeyer2018).

Most patients in EoL care receive ABT (Macedo et al. Reference Macedo, Nunes and Ladeira2018), with varying prescription rates reported in the literature. While some studies indicate up to 90% of hospitalized cancer patients receive ABT in the last week of life (Campoa and Reis-Pina Reference Campoa and Reis-Pina2022), others report lower percentages, such as 48% in the last week of life (Helde-Frankling et al. Reference Helde-Frankling, Bergqvist and Bergman2016) and 82.2% in the last 3 days of life (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Yoo and Keam2023). Notably, patients who received PC in the study by Kim et al. had a lower ABT rate (73.5%) compared to those without PC (88.3%) (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Yoo and Keam2023). Our study found that patients in the NPC group received ABT more frequently in the last 30 and 14 days of life. Deciding to use ABT in EoL cancer patients poses an ethical dilemma due to the potential for unnecessary suffering prolongation (Stiel et al. Reference Stiel, Krumm and Pestinger2012). The administration of ABT should be individualized, considering its limited impact on disease progression or symptom control.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this study represents the first comprehensive analysis in México investigating the frequency of admissions to acute settings and EoL medical interventions among cancer patients, with a focus on the timing of admission to PC services and whether they received care from these services. This is relevant since most of the studies addressing this matter are conducted in settings with varying conditions of health-care access. Cultural differences play a crucial role, as intervention approaches may vary from country to country. This study was conducted in a tertiary care referral hospital, providing a significant advantage due to its large sample size. Additionally, our results contribute to the existing evidence on the importance of early incorporation of PC in patients with cancer at any stage to improve QoL.

This research has some limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. First, this study only focused on descriptive questions. Second, although studies have used the cutoff of 90 days or more to define EPC, this remains an arbitrary point as there is no universal consensus, and therefore other time cutoffs may or may not find similar results to ours. Fourth, our results might be influenced by indication bias. This is because patients who initiate PC near the end of their lives often have more unstable health conditions, increasing the likelihood of receiving care in acute medical settings during the last days of life. Finally, other variables such as functional status, QoL, and reason for admission to the ICU or ED were not considered.

Conclusions

Our study reported a high prevalence of admissions to acute hospital settings and EoL medical interventions among deceased cancer patients who received LPC and those who never received PC. Additionally, a low prevalence of patients receiving EPC was observed, indicating that early integration of PC remains challenging.

These findings highlight the necessity to enhance collaboration within the multidisciplinary team, particularly between the PC team and oncologists. Early referral to the PC team for both outpatients and hospitalized patients can help prevent therapeutic obstinacy, offering comfort and well-being interventions and significantly improve the QoL for patients and their caregivers. Lastly, further studies with greater methodological rigor are needed to more thoroughly assess the benefits of the early incorporation of cancer patients into PC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Adriana Peña-Nieves (MSc.) for her guidance.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.