Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common health challenges among women worldwide. It is a global disease, with a significant burden and its incidence continues to rise especially in sub-Saharan Africa. About 168,690 cases of breast cancer and 74,072 breast cancer deaths were recorded in Africa in 2018 (Sharma Reference Sharma2021). The World Health Organization estimates that there are around 250,000 cases of breast cancer each year in Nigeria (Kuteyi Reference Kuteyi2021). Of these, nearly 10,000 deaths occur annually. Nigeria has the highest number of deaths from breast cancer in Africa (Adewale Adeoye Reference Adewale Adeoye2023; Akintunde et al. Reference Akintunde, Phillips and Oguntunde2015; Sharma Reference Sharma2021). Previous studies have examined the level of awareness of breast cancer and its predisposing factors among females (Omotara et al. Reference Omotara and Yahya2012; Ghrayeb et al. Reference Ghrayeb, Rimawi and Nimer2018); knowledge and beliefs about breast cancer prevention among black women (Akhigbe and Omuemu Reference Akhigbe and Omuemu2009); and breast cancer in young women (Ntekim, Nufu and Campbell Reference Ntekim, Nufu and Campbell2009); patients’ experiences of family members reactions to diagnosis of breast cancer and support in the management of cancer (Adejoh et al. Reference Adejoh, Olorunlana and Adejayan2020).

Studies (Bazzi et al. Reference Bazzi, Clark and Winter2018; Liao et al. Reference Liao, Chen and Chen2010; Kuteyi and Victor Reference Kuteyi and Victor2020) have shown that women are more likely to withstand breast cancer and its aftermath if they have at least 1 supportive confidant. Breast cancer can be particularly difficult for patients who have yet to build social support networks within their own families (Froude et al. Reference Froude, Rigazio-digilio and Donorfio2017). Women with breast cancer often need additional support in coping with issues associated with the disease and its treatment, both the physical aspects and the psychosocial effects.

To date, the literature documenting the relationship between social capital and health is available but the role of social capital as a source of support in the management of breast cancer has been limited. Against this background, this study provides new thinking and insights on how family cohesion, expressed through positive relationships between spouses, family members, relatives, and friends; involvement in religious activities; and neighbors’ awareness of breast cancer, can influence its management.

Social capital theory

In our study on breast cancer management in Lagos, Nigeria, we employed social capital theory to investigate the significance of social relationships, networks, and resources in enhancing well-being and promoting collective action norms (Eriksson Reference Eriksson2011; Kawachi et al. Reference Kawachi, Subramanian and Kim2008; Ogden et al. Reference Ogden, Morrison and Hardee2014). This theory illuminated how individuals’ affiliations and networks could impact their health outcomes and access to resources in times of need. By utilizing key social capital constructs such as bonding, bridging, linking, access to information and resources, and social support and coping (Szreter and Woolcock Reference Szreter and Woolcock2004), our research provided valuable insights. We examined the influence of various social capital forms on breast cancer management, emphasizing the pivotal role of strong family relationships (bonding social capital) in offering emotional and instrumental support to patients. Bridging social capital connected patients to additional support networks beyond their immediate families, while linking social capital indirectly involved religious groups in providing support (Poortinga Reference Poortinga2012; Putnam Reference Putnam1993). Moreover, social capital facilitated access to information and resources, empowering patients to make informed health decisions (Altschuler et al. Reference Altschuler, Somkin and Adler2004; Berkman and Glass Reference Berkman, Glass, Berkman and Kawachi2000). Ultimately, our argument is that social support (Gbenga Reference Gbenga2008; Smith Reference Smith2004; Thurston Reference Thurston2010) from family, friends, and religious communities can positively influence coping strategies, enhancing patients’ mental well-being and overall quality of life during breast cancer management.

The social context of Nigeria

Nigeria, a culturally diverse nation comprising around 200–250 ethnic groups, is known for its pluralistic society (Gbenga Reference Gbenga2008; Otite Reference Otite1991). These groups, divided by linguistic dialects, exhibit varying family systems, from monogamous to polygamous, forming the foundation of Nigerian households. A typical Nigerian family consists of a man, his wife or wives, children, and often, extended family members such as grandchildren and stepchildren. These family structures are typically categorized into nuclear or extended families, depending on the marriage system employed, whether traditional, state-sanctioned, or Christian (Otite Reference Otite1991). Religion plays a significant role in Nigerian society, with the coexistence of Christianity, Islam, and indigenous beliefs, all involving intricate rituals and the veneration of supreme and localized deities. These religious practices greatly influence health-care choices and where individuals seek treatment. The health-care system in Nigeria is multitiered, comprising government and private sectors. The federal, state, and local governments oversee tertiary, secondary, and primary health-care levels, respectively (Adeyemo Reference Adeyemo2005). While government hospitals once offered free treatment until 1984 (Orubuloye et al. Reference Orubuloye, Caldwell and Caldwell1991), cancer care in Nigeria predominantly requires out-of-pocket payments. Notably, the country faces a substantial breast cancer burden in Africa, highlighting the pressing need for improved access and affordability (Adewale Adeoye Reference Adewale Adeoye2023; Fregene and Newman Reference Fregene and Newman2005; Sharma Reference Sharma2021).

Methods

This study employed qualitative research methods, conducting interviews with women undergoing breast cancer treatment at a University Teaching Hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Qualitative research was chosen for its ability to provide in-depth insights into how individuals perceive and experience issues, enabling participants to share their experiences and yielding rich and original information.

A total of 23 women with breast cancer participated in the study. Health professionals at the clinic recruited participants during their appointments, ensuring they had been diagnosed with breast cancer at least 6 months before the interviews and were currently receiving treatment. We assume that this waiting period would allow participants to cope with the initial shock and denial. One of the authors conducted 25- to 30-minute interviews, audio recording each session. One participant couldn’t participate due to time constraints. Two interviews were conducted in Yoruba language, and 5 in pidgin English. Participants were interviewed individually in a clinic room using an in-depth interview guide to delve into their personal experiences. Verbal informed consent was obtained after explaining the study’s purpose. The University of Lagos Teaching Hospital’s ethical board granted permission, with ethical approval number ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/1484.

The study explored breast cancer patients’ perspectives and the influence of social capital on their illness management, addressing their interactions with spouses, changes in social activities, and support from family and friends during the breast cancer experience. It also investigated connections with neighbors before and after diagnosis, as well as assistance from religious groups. The research adopted a flexible approach, allowing questions to evolve based on participants’ responses. For example, participants who were widowed or unmarried were not queried about spouses but instead about the support received from relatives. All interviews were transcribed, and non-English interviews were expertly translated, with the authors ensuring consistency and accuracy in the translations.

Data analysis

The research data was analyzed using content analysis. Content analysis is a method of analyzing written, verbal, and non-verbal (including visual) communication (Cole Reference Cole1988; Harwood and Garry Reference Harwood and Garry2003) and can be used to describe and quantify phenomena (Sandelowski Reference Sandelowski1995). Content analysis was used for this study as themes or categories, and subthemes, or subcategories were created from the raw data. The method is most often applied to verbal data such as interview transcripts (Schreier Reference Schreier2012). There are 2 types of content analysis; deductive and inductive content analysis (Lauri and Kyngäs Reference Lauri and Kyngäs2005). This study used inductive analysis as it enables us to derive categories or themes from the data (Kyngäs and Vanhanen Reference Kyngäs and Vanhanen1999).

The study employed content analysis, a method used to analyze various forms of communication, both verbal and non-verbal (Cole Reference Cole1988; Harwood and Garry Reference Harwood and Garry2003), enabling the description and quantification of phenomena (Sandelowski Reference Sandelowski1995). The method is utilized to derive themes and subthemes primarily from interview transcripts (Schreier Reference Schreier2012). Inductive analysis, as recommended by Lani and Kyngas (Reference Lauri and Kyngäs2005) and Kyngas and Vanhanen (Reference Kyngäs and Vanhanen1999), allowed for the direct generation of categories and themes from the data. The inductive content analysis process comprises 3 stages: open coding, where transcripts are repeatedly reviewed, and notes and headings are created to ensure comprehensive coverage (Burnard Reference Burnard1991; Hsieh and Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). During this phase, categories and themes emerge organically. Following open coding, these categories and themes are organized into higher-order headings (Burnard Reference Burnard1991). Abstraction involves labeling each category or theme descriptively, with similar subcategories or subthemes grouped under overarching categories or themes (Kyngäs and Vanhanen Reference Kyngäs and Vanhanen1999). Unique subthemes are preserved in this process.

To enhance fidelity and interpret data accurately, 3 authors independently conducted the analysis, commencing with data coding and subsequently reconciling any discrepancies through multiple data reviews (Burla et al. Reference Burla, Knierim and Barth2008; Schreier Reference Schreier2012). Quotations were also incorporated to signify the credibility of the findings (Polit and Beck Reference Polit and Beck2012; Sandelowski Reference Sandelowski1995). This rigorous approach ensured a robust and reliable analysis of the data.

Three themes and 5 subthemes were identified: family cohesion with subthemes (relationship with spouses and children, negative reactions from family members, support from relatives), involvement in religious activities; relationship and support from neighbors with subthemes (disclosure of cancer status and support received and nondisclosure to neighbors). On the other hand, direct quotation of responses (that indicate the participant's voice), which entails verbatim reporting of opinions, idioms, and proverbs that support important findings in the data, were done. The direct quotations of participants were later translated into English for proper reporting.

Results

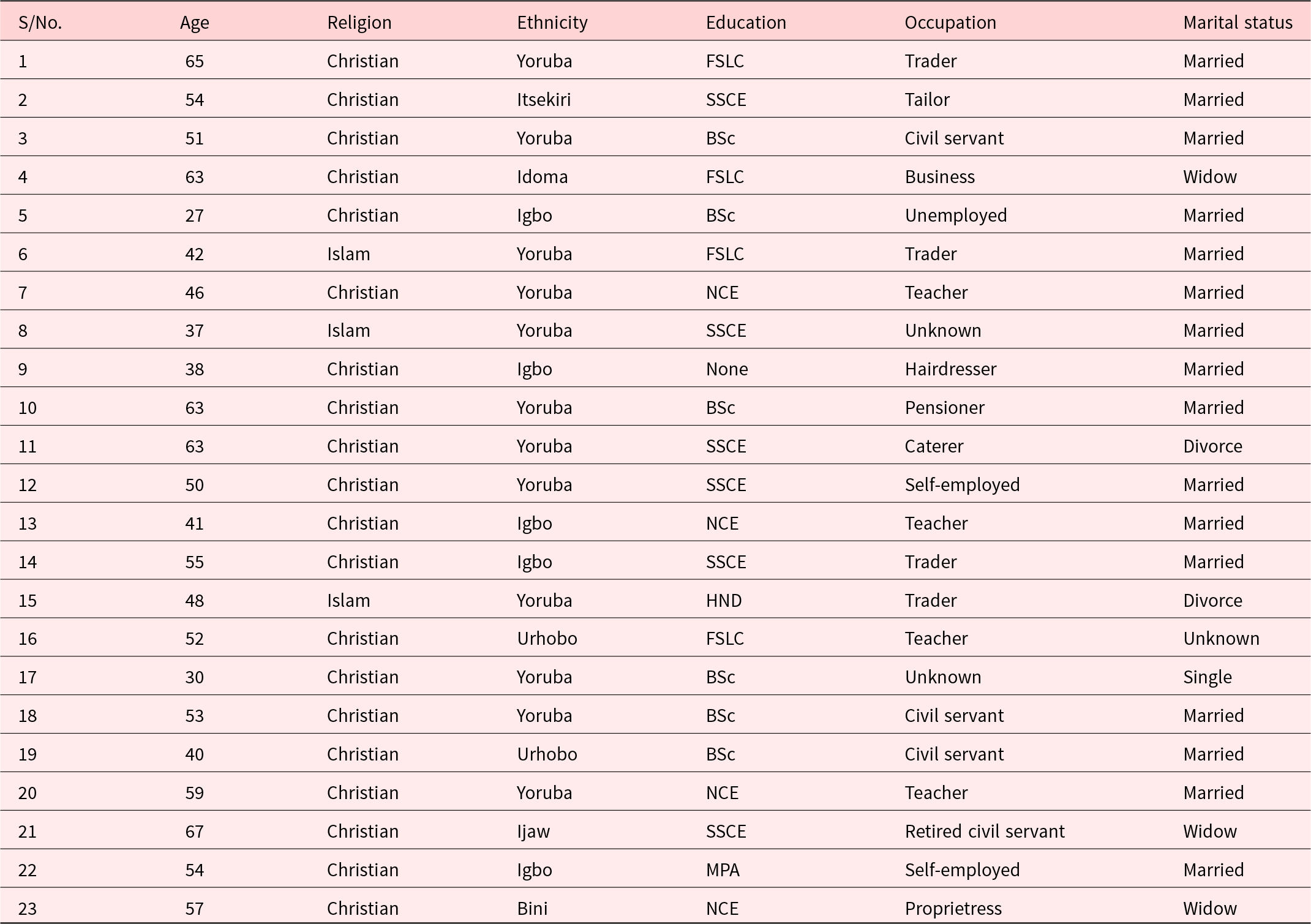

The above Table 1 shows the profiles of the participants. All participants are female, with the youngest participant being 27 years of age and the oldest being 67 years of age. All participants in the country practice either the Christian or the Islam religion in the country with diverse ethnic backgrounds. All participants except 1 had a form of formal education. Again, all participants except 1 are in different occupations. On marital status, 1 participant was not married, 3 were widows, 2 were divorced, and 16 were married.

Table 1. Demographic profile of the participants

FSLC = First School Leaving Certificate; SSCE = Secondary School Certificate Examination; OND = Ordinary National Diploma; NCE = National Certificate of Education; Higher National Diploma; BSc = Bachelor of Science; MPA = Master of Public Administration.

Family cohesion

Family is key to every individual in Nigeria, as it provides the foundation for their future. Perceived emotional bonding, such as family cohesion, is important for patients living with cancer because it provides a source of support.

Relationships of spouses and children

The aim was to know whether cancer diagnosis and treatment affect the relationships between participants and their spouses and other family members in terms of sharing objects or other utilities at home and attending social functions together with other members of the family. The data show that the relationship between some of the participants and their spouses and children remained unchanged and the relationship contributed positively to the management of the condition. A 65-year-old participant revealed how her husband and child related to her during her cancer treatment:

He is a responsible man. I am recently staying with my child, I have left home, my child who is a nurse told me to come and stay with her so she can be taking care of me, my husband comes here to see me once in a while because we are at Owode, Ifo road [husband resides in another location]. I won’t really say something has changed because we’ve not been staying in the same house, and he still visits me where I am. (Participant 1; 65 years old)

The participant’s response highlights the presence of family cohesion. Her daughter and husband provided constant care, with the husband regularly visiting his ailing wife at their daughter’s home, emphasizing the strong familial support during her battle with the disease.

Likewise, a participant shared her husband’s unwavering support, motivating her to prioritize her health and adhere to precautions. The family’s unity instilled the determination to return home promptly for necessary treatment.

He is very nice, he is not harsh, he is very friendly. I have been doing everything, sometimes if I go out, I don’t drink, I don’t take alcohol. If I go out and I am to stay long, I don’t stay long again. I rush back home to take care of myself. (Participant 5; 27 years old)

Another participant extols the support of her husband:

My husband has been nice. I have never seen a man like him. He takes me to the hospital each time I need to go. Even when I was doing radiotherapy, you won’t believe that this man leaves the house as early as 03:00 am to EEE hospital [not real name of the hospital] just to put down my name in the register so that I’ll be one of the first persons to be attended to by the doctors. There’s no medicine or food that is recommended by the doctor that he doesn’t buy for me. He even buys and blends fruits for me to take. In fact, he’s one in a million. (Participant 22; 54 years old)

Negative reactions from family members

Cancer diagnoses disrupted family dynamics for some participants. Physical and emotional pain served as a barrier, hindering meaningful conversations and social engagements with their spouses, demanding substantial time and energy. One participant acknowledged that her interactions with her spouse had shifted, possibly due to her cancer diagnosis and the geographical separation between her treatment center and home. The participant stated:

Interaction has changed a bit. It might be due to the illness, I don’t really know, I can’t really say. Actually, I have been away since; I am just coming back. We have not really been together. I am based in Warri, and I had the treatment in Ife, so I have been in Ife since. (Participant 18; 53 years old)

The data indicates substantial support from participants’ families, with no significant changes in family dynamics post-cancer diagnosis. The main sources of support were spouses and relatives, although unmarried individuals received support from their nuclear families, while divorced or widowed participants received support from relatives. Two participants did not receive any form of support from their family members following their cancer diagnoses. They showed that the interactions between them and their family members diminished after it was established that they were suffering from cancer.

Support from relatives

Support from the relatives includes financial support as well as caring for the patients’ nuclear families. The study revealed that most of the participants received financial support from their relatives alongside the care received from such relatives by the patients’ nuclear families. This was demonstrated by a participant:

My relatives have been wonderful. Ah! I never knew they loved me like this. Especially one of my brothers. In fact, I said for the sake of this my brother, God should allow me live. He wanted taking me out of the country for my treatment, but my instinct told me to do it here in Lagos. He’s been supportive. Any money that I mentioned, he’ll tell my husband to split it into two and he’ll contribute half of it for my hospital bills. He’s been nice and caring. They wake me up every morning with prayers. I never knew they loved me this much until I became sick. I thought that with this sickness, things will be difficult but to the Glory of God, things are even becoming better. God is giving my husband business links. God has been so faithful to me. (Participant 12; 50 years old)

Involvement in religious activities

The data revealed that many of the participants were active participants in their places of worship. They received different kinds of assistance including spiritual support from those worship places. A participant affirmed that:

Yes. We have to play a role. I’m a Jehovah witness. When this started, any time I’m relieved, I try to do my spiritual activities. I go to my place of worship. Sometimes I even follow them to preach a little bit but I’m not as regular as I used to be. I carry out my spiritual activities. Whenever we have an assembly, I try my best to be there. If it comes to preaching activities, I’ll do the little I can. That’s what we Jehovah witnesses do. They encourage me a lot with the word of God. Their words are seasoned with salt and not the one that will tear someone down. That’s why I’m not afraid of going there to worship. If it’s in another church they’ll be talking about you behind your back. But they don’t do that. They are really supporting me and I’m encouraged. Even though they don’t give me physical gifts, that one is enough. (Participant 20; 59 years old)

The experience of another participant reveals the kinds of support she received, and these were social, psychological, and financial in nature:

Yes, I do. I used to be a Sunday school teacher and a member of women missionary group. They support me financially, visitations, prayers, and advice. There’s a woman in my church who has been a breast cancer survivor for 25 years that encourages me to be strong and I am really coping. (Participant 4; 63 years old)

Similarly, another participant got both monetary and spiritual support from her church as stated thus:

No, I don’t play any role in my place of worship. They (Members) sometimes give me money and pray for me. (Participant 7; 46 years old)

However, because some of the participants did not disclose their health status to members of their worship places, they could not draw on any financial assistance as stated by a participant:

Not really. I go to church as a normal human being and come back. I don’t belong to any group. My job is very demanding so there’s no need dividing myself to please somebody. But whenever I’m given any role in the church to perform, I do it. I only belong to mother’s union that’s all. None (Finance). Because I didn’t let them know about the sickness. When they don’t see me, they pray for me. That’s all. (Participant 23; 57 years old)

Relationship with and support from neighbors

The aim here is to describe participants’ relationships with their neighbors prior to the cancer diagnosis as well as the kinds of support or assistance they received from their neighbors after being diagnosed as having breast cancer.

Disclosure of cancer status and support received

Eight participants affirmed their neighbors’ support in tackling their health issues. One participant stressed the cordial relationship between her and her neighbors and made it clear that she only received moral support from them as opposed to financial assistance. This is because her neighbors believed she attends a rich church where hug financial support could come for her. She said:

Fine, cordial (Relationship with neighbours). They only give me moral support (calls) not financial support. For them they feel the church has money. (Participant 19; 40 years old)

Another participant pointed out how she received support from only a member of her neighborhood even though she related well with other neighbors but did not disclose her cancer status to them:

I have a very good relationship with my neighbours in our own house and in our area. The only neighbor that knows about it she has been sending series of information to me on WhatsApp, chatting and praying for me. When I’m less busy, I also visit her, and nobody knows what is wrong. (Participant 17; 30 years old)

A participant received both financial and moral support from her neighbors. She said:

They talk to me, they play with me, and we eat together. They always support me anytime financially and morally. (Participant 9; 38 years old)

Nondisclosure to neighbors

The study showed that the majority of the participants, specifically 16 participants, reported no support from their neighbors. Most of the participants were not close to them and so did not disclose their illness to their neighbors and so no support was expected from them in addressing their health challenge. According to a participant:

I don’t really get close to them; I just greet them. I don’t have this intimate relationship with them. None (Financial support from her neighbors). (Participant 20; 59 years old)

Apart from not being close to neighbors, some participants even declined to inform their neighbors about their health issue because of fear of being mocked as stated below:

My neighbours are Muslims and half Christians. My shop is in front of our yard and since this sickness has started, I stopped selling, none of them has asked me why I am not trading again, they never asked me, not even for one day and I am not clear. I don’t want to expose myself and I know that God is in control. They will just be looking at me, maybe they feel if I don’t come out, I will not eat but I am eating by the grace of God. I did not tell them about the sickness because they will mock me. (Participant 14; 55 years old).

Discussion of findings

This study delved into the impact of social capital on breast cancer management, focusing on family cohesion, support from relatives, involvement in religious activities, and neighborly support. The analysis highlighted the crucial role of family cohesion in breast cancer management, with over half of participants receiving multifaceted support from family members. These individuals uniformly acknowledged the emotional and financial support from family members as a driving force in their disease management. Family cohesion, particularly in relationships with spouses and children, emerged as a pivotal factor for those facing breast cancer. Participants attested that this cohesion fosters emotional well-being and forms a protective shield for individuals dealing with breast cancer. The exhibited social capital involves informal, unregulated exchanges of information and resources within the family system. This study aligns with a Chinese study that explored the relationship between family functioning and breast cancer patients (He et al. Reference He, Yang and He2022). The findings underscore the significance of social capital, particularly family cohesion, in supporting breast cancer patients through various forms of assistance, mirroring findings in other cultural contexts like China.

Aside from the support from children and spouse, extended family members also constitute a source of support to those living with breast cancer. Most of the participants acknowledged that their relatives have been supportive, even though some of them may not contribute financially. This shows that the support system goes beyond financial assistance. Spouses provide emotional support, but mainly provide instrumental support, while relatives and friends are the most important sources of emotional support. This finding aligns with previous studies (Bazzi et al. Reference Bazzi, Clark and Winter2018; Liao et al. Reference Liao, Chen and Chen2010), suggesting that women with supportive confidants, such as relatives and friends, are better equipped to cope with breast cancer.

Our study shows that breast cancer patients also receive support from friends and neighbors around them. From the responses, it was found out that some neighbors give helping hands to patients with breast cancer around them. It was also discovered that some patients did not disclose their cases to their neighbors to avoid being ridiculed. This concealment might have some implications on the sufferer, as it will limit the neighbor’s effort to support the patient. It further negates the aspect of social capital that emphasize trust, reciprocity, information, cooperation, and cohesion. This is often detrimental to the health of the patient. This is in line with the arguments of previous studies (Kawachi et al. Reference Kawachi, Kennedy and Glass1999; Harpham et al. Reference Harpham, Grant and Thomas2002; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Matthews and Shoff2011) that living in a neighborhood with low levels of trust and integration increases the odds ratio for poor self-rated health.

The study shows the role of participation in religious activities in the management of breast cancer. This study revealed that participants who received support from active participation in religious activities were those who disclosed their breast cancer status to members of such religious groups. Supports received include financial support, emotional support, visitations, prayers, and advice from their brethren. Therefore, it can be argued that there is a relationship between participation in religious activities and the management of health challenges like breast cancer. This conclusion is not too far from the observation of Harding, Flannelly, Weaver, & Costa (Reference Harding, Flannelly and Weaver2005) that faith can give a suffering person a framework for finding meaning and perspective through a source greater than self, and it can provide a sense of control over feelings of helplessness. Religious practice can provide access to social networks and established forms of assistance, including monetary, and pastoral care during times of acute distress etc.

This study found that the nature of the relationship with neighbors and those living with breast cancer played an important role in determining the kind of support to receive. As revealed by the study, those participants who had established cordial relationships with their neighbors recorded enormous support from members of their neighborhood. In contrast, those participants, who did not have intimate relationships in their neighborhood affirmed that no support of any kind came to them from their neighbors.

Community and interpersonal interactions are important in offering assistance to those suffering health challenges in Nigerian and African cultures. Support is frequently tied to established social connections, such as places of religion, friends, and neighbors. The culture is community-oriented, with an emphasis on mutual help and responsibility to one another. Openly acknowledging health conditions fosters empathy and identification, making support more accessible. Relationships, particularly those formed within families, religious institutions, and friendship circles, act as a social safety net, providing emotional, financial, and practical support. The level of support depends on trust and openness between individuals, as discussing health conditions may initially be hindered by stigma and fear of judgment. However, trust-building enables individuals to share their struggles and receive necessary support. Religious institutions wield considerable power, fostering a sense of kinship and camaraderie among believers. When people open up about their health problems in houses of worship, they can receive prayers, emotional support, and practical help. Finally, Nigerian and African cultures emphasize the significance of trust and transparency when seeking help from social networks during health crises, recognizing the impact of established ties and societal perceptions on assistance.

Policy implication

Family support significantly impacts women living with breast cancer, alleviating fears, anxiety, and suffering in managing the disease. Therefore, including a family member on the care team should be a hospital policy to enhance effective management. Social work professionals in Nigeria should advocate for an increased role of family members in breast cancer management.

Conclusion

Our findings show how family cohesion, relatives, friends, and neighbors and participation in religious activities influence the management of breast cancer through engagement in behaviors that are supportive and encouraging. Supportive behaviors include the provision of emotional support, such as empathy and alleviation of breast cancer-related distress, and the provision of instrumental support such as paying for medications and helping participants apply drugs.

Through the application of social capital theory, this study provided insights into the impact of support, compassion, and resources originating from social bonds within family, community, and religious settings on breast cancer management in Lagos, Nigeria. The theory offered a structured approach to investigate the various facets of social support and their potential implications for dealing with breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate all the respondents for their participation in the study and all the internal reviewers for their comments.

Funding

This study has no formal funding. All views expressed are that of the authors and not that of their respective university.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.