Introduction

“Person-centered” care is the main approach taken in modern medicine. Its development resulted from the need for a wider and more comprehensive model than the one offered by the classic biomedical model which concerned itself mostly with the physical aspects of illness and disease (Holman and Lorig Reference Holman and Lorig2000; Laine and Davidoff Reference Laine and Davidoff1996). The person-centered model takes into account not only biological factors but psychosociological and cultural factors as well (Christensen and Johnson Reference Christensen and Johnson2002; Engel Reference Engel1977). Patient-centered care aims to focus on patients’ needs and preferences (Laine and Davidoff Reference Laine and Davidoff1996), and is strongly correlated with patients’ health improvement (Anderson Reference Anderson2002), symptom reduction (Putnam and Lipkin Reference Putnam and Lipkin1995), greater satisfaction (Little et al. Reference Little, Everitt and Williamson2001), greater adherence (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Daughtridge and Sloane2002; McLane et al. Reference McLane, Zyzanski and Flocke1995), and a reduction in diagnostic errors (DiMatteo and Lepper Reference DiMatteo, Lepper, Jackson and Durn1998).

It was person-centered care that led to the development and flourishing of research into the patient–physician relationship (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Glasgow and Davis2001). It has been established that patient’s involvement in treatment, shared decision-making, and the collaborative patient–physician relationship are integral to good medical care (Ha and Longnecker Reference Ha and Longnecker2010; Kjeken et al. Reference Kjeken, Dagfinrud and Mowinckel2006). Furthermore, the quality of patient–physician communication is associated with patients’ adherence and satisfaction (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Hewlett and Hughes2003; Mahomed et al. Reference Mahomed, Liang and Cook2002). In short, it is clear that the patient–physician relationship is a fundamental part of patient-centered care.

The literature conceptualizes the “working alliance” as a main aspect of the patient–physician relationship. The working alliance is a well-researched concept taken from the field of psychotherapy, commonly defined as the perception of the emotional bond established in the patient–therapist dyad and the agreement between the 2 concerning therapy goals and the tasks necessary to achieve them (Bordin Reference Bordin1979; Hatcher and Barends Reference Hatcher and Barends2006). It is important to note that in the current manuscript, it is the perceived working alliance to which we are referring. The working alliance in psychotherapy is one of the most reliable and consistent factors in predicting psychological treatment outcomes, such as patients’ well-being and therapeutic gains (Baldwin et al. Reference Baldwin, Wampold and Imel2007; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Garske and Davis2000; Mead and Bower Reference Mead and Bower2002).

The patient–physician working alliance is similar to the patient–psychotherapist working alliance. It combines cognitive, behavioral, and emotional aspects, and comprises 3 elements: (1) goals – a mutual understanding regarding realistic treatment targets, (2) tasks – an agreement on relevant and beneficial operations required to achieve treatment goals, and (3) bond – a personal and emotional patient–physician relationship based on mutual trust and confidence (Bordin Reference Bordin1979; Fuertes et al. Reference Fuertes, Boylan and Fontanella2009). A relation has been found between a good medical working alliance, on one hand, and the patient being an informed and active partner in the treatment decision-making process, on the other hand (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Fuertes and Keitel2011; Fuertes et al. Reference Fuertes, Boylan and Fontanella2009; Holman and Lorig Reference Holman and Lorig2000); these latter characteristics are further related to patient adherence (Holman and Lorig Reference Holman and Lorig2000) and satisfaction (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Fuertes and Keitel2011).

The patient–physician working alliance is especially essential in the oncological setting, due to the unique characteristics of the relationship between the two: namely, a long-term and intensive relationship maintained in the presence of coping with the physical and mental suffering of a life-threatening illness (Epstein and Street Reference Epstein and Street2007). Nevertheless, very little research has been conducted in this field, particularly from the oncologist’s point of view. From the patient’s perspective, previous cancer-specific studies have revealed that a good patient–oncologist working alliance is related to patient’s better quality of life, illness acceptance, perceived social support, and treatment adherence, as well as better adjustment to cancer-related losses (Mack et al. Reference Mack, Block and Nilsson2009; Trevino et al. Reference Trevino, Fasciano and Prigerson2013). As such, it is important to deepen and extend the knowledge of the working alliance in the oncological setting in order to improve treatment and outcomes. Some studies already conducted in this field have examined the dyad in the context of predispositions. Fuertes et al. (Reference Fuertes, Boylan and Fontanella2009) found that when patients rated working alliance with their physicians as good and caring, they reported higher self-efficacy and felt they had more control over and influence on treatment outcomes. This connection between patients’ perception of a good patient–physician working alliance and patients’ sense of control over their condition suggests that locus of control predispositions and beliefs of personal efficacy might have an important role in the patient–physician relationship.

A locus of control predisposition represents the way in which individuals comprehend the events impacting their lives (Levenson Reference Levenson1974; Rotter Reference Rotter1966) and relies on individuals’ understanding of causality as being controlled either by their own actions (internal locus of control) or, alternatively, by external factors, such as “powerful others” or “chance” (external locus of control). Seeking to understand why things happen (i.e., causality) derives from the human need for understanding and giving meaning to life events (Kelley Reference Kelley1973). Perceived locus of control influences one’s expectations and behavior (Rotter Reference Rotter1966).

Individuals who have a higher internal locus of control seem to be more eager to learn and strive for success (Colquitt et al. Reference Colquitt, LePine and Noe2000; Ng et al. Reference Ng, Sorensen and Eby2006; Spector Reference Spector1982). Those with a higher external locus of control, on the other hand, report greater stress and depression (Benassi et al. Reference Benassi, Sweeney and Dufour1988; Maltby et al. Reference Maltby, Day and Macaskill2007). Moreover, people with a higher “powerful others” locus of control, specifically, seem to use passive coping strategies, such as avoidance, and often fail in their attempt to have a sense of control (Brosschot et al. Reference Brosschot, Gebhardt and Godaert1994; Galvin et al. Reference Galvin, Randel and Collins2018; Lefcourt Reference Lefcourt1981). Others, who have a higher “chance” locus of control, seem to be less accomplished and to have lower self-esteem and a lesser ability to struggle with difficulties (Brosschot et al. Reference Brosschot, Gebhardt and Godaert1994; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Thaker and Sun2017; Crandall and Crandall Reference Crandall, Crandall and Lefcourt2013). Perceived locus of control has an influence not only on one’s cognitions and behaviors; it also appears to affect one’s relationships with others (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Thomas and Charles2005; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Lefcourt and Holmes1986; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Tomlinson and Noe2010). Internal locus of control is associated with better romantic relationships (Kent et al. Reference Kent, Matthews and White1984; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Lefcourt and Holmes1986) and with better employee–employer relationships (Kinicki and Vecchio Reference Kinicki and Vecchio1994; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Thomas and Charles2005). However, to the best of our knowledge, no study to date has tested the patient–oncologist working alliance from a dyadic perspective and, in particular, its relation to locus of control. This association may be of great interest and importance due to issues of control and conflicts that are part of the coping process along the illness trajectory (Epstein and Street Reference Epstein and Street2007); this association is also of interest given the basic inequality that characterizes the oncologist–patient relationship. In the present study, we used the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) to examine patient–oncologist dyads and the contribution of their locus of control predispositions to their own perceived working alliance and to their dyadic partners’ perceived working alliance. Based on previous studies (Colquitt et al. Reference Colquitt, LePine and Noe2000; Kent et al. Reference Kent, Matthews and White1984; Kinicki and Vecchio Reference Kinicki and Vecchio1994; Maltby et al. Reference Maltby, Day and Macaskill2007; Spector Reference Spector1982; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Tomlinson and Noe2010), we hypothesized that we would find a positive actor effect of internal locus of control on working alliance, and a negative actor effect of “powerful others” locus of control and “chance” locus of control on working alliance, for both patients and oncologists. In addition, we tested, exploratorily, whether there would be partner effects of locus of control on working alliance: that is, partner’s internal locus of control would be positively associated with actor’s working alliance, but partner’s “powerful others” locus of control and “chance” locus of control would be negatively associated with it.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 103 patient–oncologist dyads who were recruited at 2 oncology institutes in Israeli hospitals: Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan and Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem. Out of 12 oncologists who had worked for at least 1 year in the hospital’s oncology institute and were approached, 10 participated in the study, and 2 (16.6%) refused, due to workload. Nine of the 10 oncologists were specialist oncologists and 1 resident. Out of the 172 patients of the 10 participating oncologists who had been in their care for at least 3 months and were asked to participate, 103 agreed to participate in the study (10–12 patients per oncologist), and 69 (40.1%) refused due to lack of interest. Patients differed in the type of cancer diagnosis. They were required to be at least 18 years of age and to have had 3 or more routine outpatient oncology visits with their oncologists during the course of their illness.

Procedure

Data were collected between May and July 2019. After receiving approvals, researchers recruited the oncologists, who signed informed consent forms and completed demographic details and the locus of control questionnaire, either by hand or by computer. The patients were approached during the participating oncologists’ clinic days; while they were waiting for their appointments, these patients were asked to participate in the study, signed informed consent forms, and completed demographic details and the locus of control questionnaire, either by hand or by computer. At the end of their appointment, oncologists and patients were asked to complete the working alliance questionnaire. Oncologists completed a working alliance questionnaire for each of their 9–12 patients who participated in the study. Patients’ medical information was taken from patients’ medical charts.

Measures

Sociodemographic and medical variables

The sociodemographic questionnaire consisted of personal information such as age, gender, and marital status. The medical information consisted of questions regarding cancer diagnosis, cancer stage, time since diagnosis, and treatment modalities.

Working alliance

The working alliance was evaluated by the Working Alliance Inventory Short Revised Form (WAI-SR; Horvath and Greenberg Reference Horvath and Greenberg1989). A self-report questionnaire, the WAI-SR, consists of 12 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale which assesses the 3 subscales of the working alliance: goals (e.g., “Dr.___ and I cooperate in determining my goals”), tasks (e.g., “I believe the way we work on my health problems is the right way”), and bond (e.g., “I feel my physician appreciates me”). We decided to refer only to the working alliance total score, on the basis of previous studies (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Fuertes and Keitel2011; Epstein and Street Reference Epstein and Street2007; Fuertes et al. Reference Fuertes, Boylan and Fontanella2009; Mack et al. Reference Mack, Block and Nilsson2009; Trevino et al. Reference Trevino, Fasciano and Prigerson2013) and on the very strong positive correlations between all 3 working alliance subscales that were found in the current study: all correlations were above .9 for patients and oncologists. The questionnaire was adjusted to the medical context by Bar-Sela et al., and its reliability and validity have been demonstrated (Bar-Sela et al. Reference Bar-Sela, Mitnik and Lulav-Grinwald2016; Rotman Reference Rotman1999). In the present study, oncologists completed the “therapist” version, and patients completed the “patient” version. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was satisfactory for the patients’ working alliance total score (.90) and for the oncologists’ working alliance total score (.95).

Locus of control

The “internal, powerful others, and chance” (IPC) locus of control scale is a measure of individuals’ locus of control (Levenson Reference Levenson1974; Rotter Reference Rotter1966). It consists of 24 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale, divided into 3 independent 8-item locus of control subscales: “internal” locus of control, or the degree of people’s faith in their own capacity to control the outcome of their life’s events (e.g., “Whether or not I get to be a leader depends mostly on my ability”); “powerful others” locus of control, or the extent to which people feel that their life events are controlled by influential others such as doctors, leaders, or God (e.g., “I feel like what happens in my life is mostly determined by powerful people”); and “chance” locus of control, or the extent to which people feel that their life events are subject to the whims of chance or fate (e.g., “To a great extent my life is controlled by accidental happenings”). Each subscale produces a sum score ranging from 8 to 48. In the current study, 2 items that significantly lowered the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) were removed from the data analysis: 1 item from the “internal” locus of control (“How many friends I have depends on how nice a person I am”) and 1 item from the “chance” locus of control (“I have often found that what is going to happen does happen”). The internal reliability for the locus of control subscales ranged from .63 to .76 for patients, and from .67 to .82 for oncologists.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 21.0; IBM Crop., NY, USA). In order to test whether the nesting of observation within oncologists was symmetrically associated with the results, we first estimated a null model for each of the working alliance subscales: goals, tasks, and bond. This model included only the working alliance variables adjusted for the effects of the oncologists. The model was tested with the linear mixed-effects model procedure of the SPSS with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. The effect of the oncologists was found to be nonsignificant (goals: p = .432; tasks: p = .847; bond: p = .267). Therefore, we used a single-level analysis.

To address our research question of measuring the interdependence between patients and oncologists in the context of the association between locus of control and working alliance, we used the APIM (Cook and Kenny Reference Cook and Kenny2005; Kashy and Kenny Reference Kashy and Kenny2000; Kenny Reference Kenny1996; Kenny et al. Reference Kenny, Kashy and Cook2006; Tambling et al. Reference Tambling, Johnson and Johnson2011). By applying the APIM, it is possible to calculate how people’s independent variable has an effect on their own dependent variable (i.e., actor effect) as well as on their partner’s dependent variable (i.e., partner effect). As Cook and Kenny (Reference Cook and Kenny2005) wrote: “APIM is a model of dyadic relationships that integrates a conceptual view of interdependence.” In the current study, we examined whether oncologists’ locus of control had an effect on their own working alliance (actor effect) and on their patients’ working alliance (partner effect) as well as whether patients’ locus of control had an effect on their own working alliance (actor effect) and on their oncologists’ working alliance (partner effect). Model parameters were estimated through structural equation modeling using Analysis of a Moment Structure (AMOS) (version 21.0; IBM Corp.).

Results

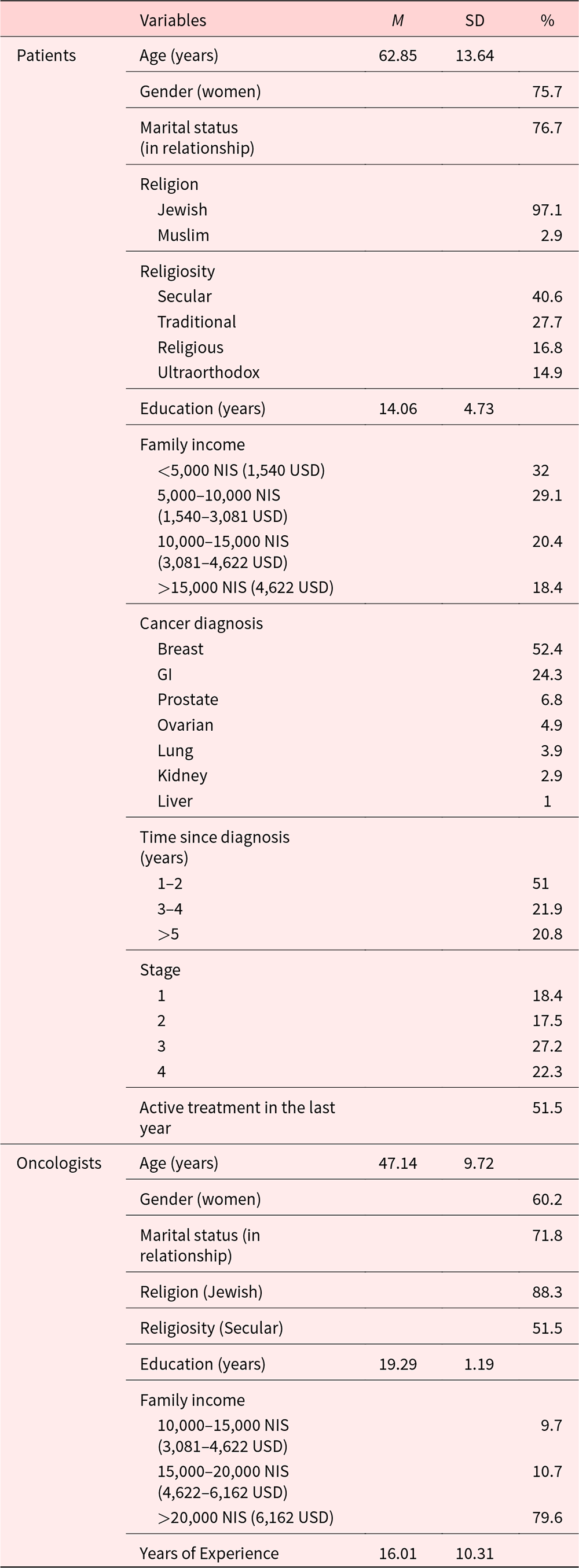

Participants’ sociodemographic and medical backgrounds are summarized in Table 1. Patients’ mean age was 62.85 years, and 75.7% were women. The most common cancer types were breast and gastrointestinal and were distributed along different disease stages. It should be noted that the greater number of women in the sample is compatible with the high incidence of breast cancer, which has been reported to be the most common type of cancer in women globally (Han et al. Reference Han, Guo and Wang2013). About half of the patients had been diagnosed with cancer during the previous 2 years and received treatment during the previous year. Among oncologists, the mean age was 47.14 years, and 60.2% of them were women.

Table 1. Demographic and medical baseline data of patients and oncologists

GI = gastrointestinal.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients and analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses were used to examine associations between the main sociodemographic variables and working alliance, which is interpreted as one’s perception of the mutual relationship and cooperation between the oncologist and the patient. These analyses revealed a significant positive correlation between oncologists’ age and their working alliance score (r = .202, p = .041). In addition, a significant association between patients’ gender and oncologists’ working alliance, T(102) = 41.396, p < .001, was found. Oncologists reported a better working alliance with their male patients than with their female patients (male: M = 6.783, SD = .585; female: M = 6.199, SD = .711).

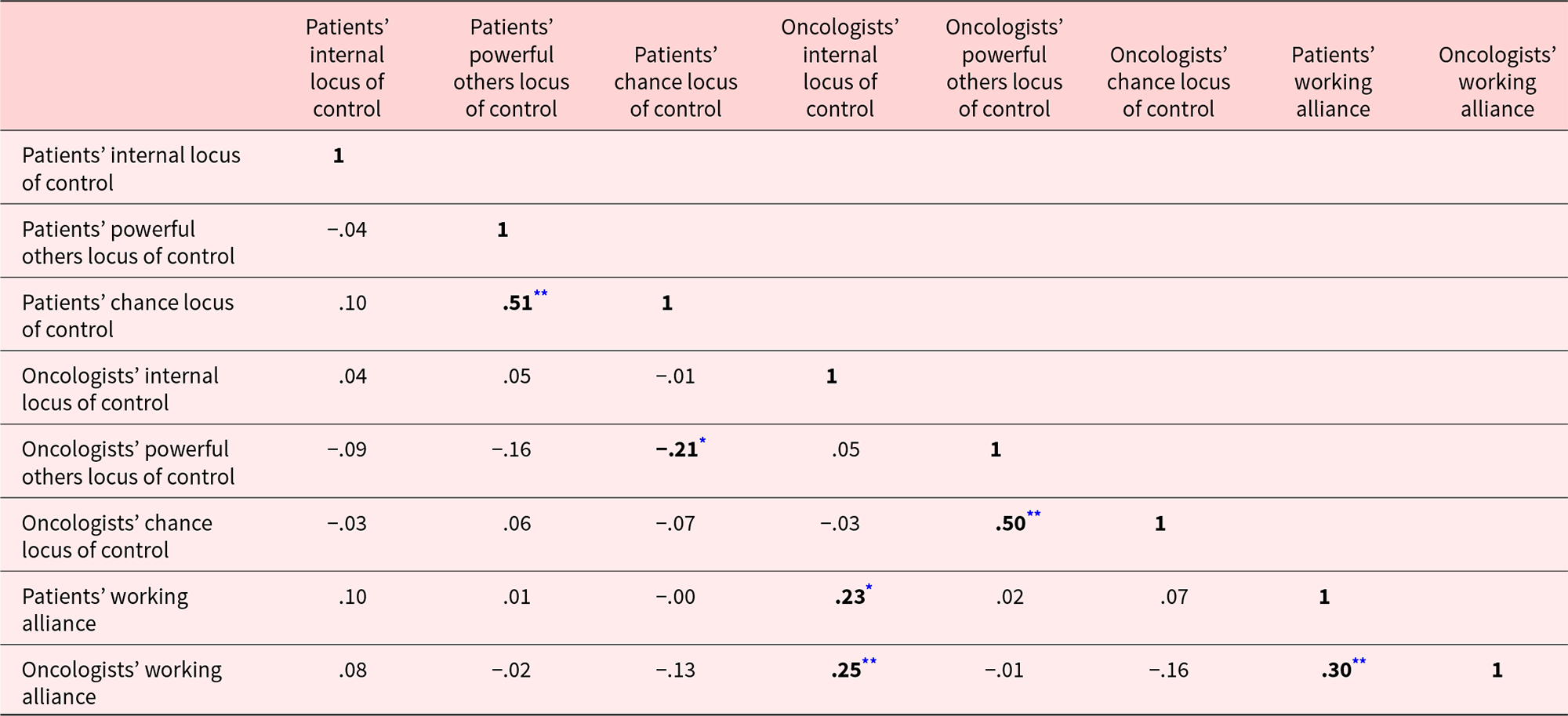

Table 2 presents Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the study’s main variables: locus of control and working alliance. As predicted, both external locus of control types (“powerful others” and “chance”) were found to be strongly and positively correlated with each other but not with internal locus of control, for both patients and oncologists. Oncologists’ internal locus of control was found to be positively correlated with patients’ and oncologists’ working alliance. Moreover, a medium correlation was found between patients’ and oncologists’ working alliance.

Table 2. Correlations between patients’ and oncologists’ locus of control subscales: internal, powerful others, and chance, and working alliance

** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed).

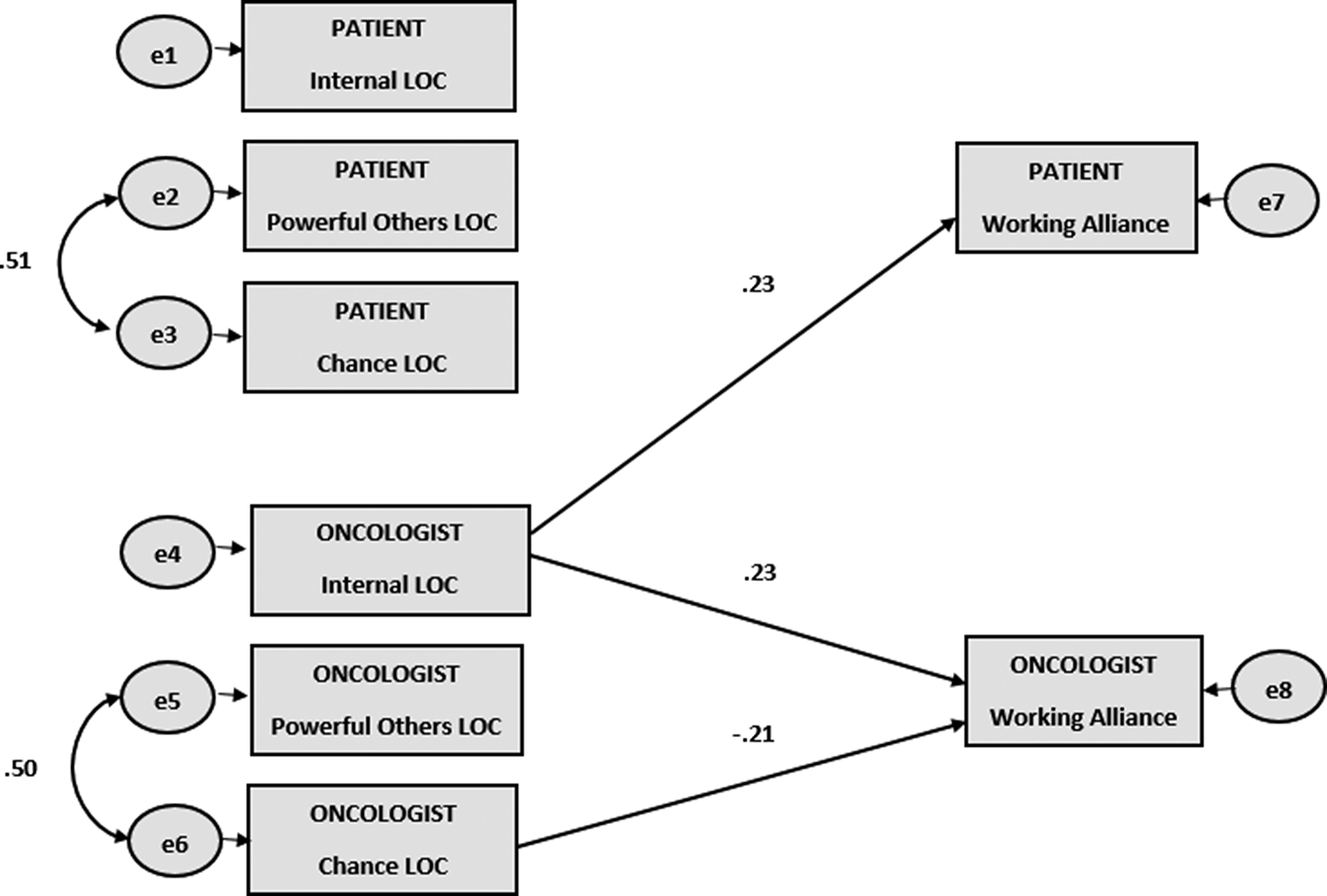

In the present study, we used the APIM to estimate 2 actor effects: the relation between patients’ locus of control and their own working alliance, and the relation between oncologists’ locus of control and their own working alliance. In addition, we estimated 2 partner effects: a relation between patients’ locus of control and their oncologists’ working alliance, and a relation between oncologists’ locus of control and their patients’ working alliance. The APIM included the 3 locus of control subscales (IPC) as an independent (predictor) variable and the total score of the working alliance as the outcome variable (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Significant effects of the actor–partner interdependence model of locus of control (in figure initials as Locus of Control (LOC)) and working alliance (standardized coefficients).

e: error.

Goodness-of-fit indices were satisfactory: χ2 (9) = 10.494, p < .312; CMIN/DF = 1.166; CFI = .981; RMSEA = .040 (90% CI: .000–.123). A significant actor effect was found: a positive relation between oncologist internal locus of control and oncologist working alliance, β = .23 (p = .011). Another significant actor effect was found: a negative relation between oncologist “chance” locus of control and oncologist working alliance, β = −.21 (p = .047). In addition, a significant partner effect was found: a positive relation between oncologist internal locus of control and patient working alliance, β = .23 (p = .014).

Discussion

Findings from the current study suggest an interesting and important association between patient–oncologist working alliance and locus of control, and highlight the significance of internal locus of control over external locus of control. Moreover, the results emphasize the important role played by oncologists in the establishment of a good alliance with their patients. Oncologists’ internal locus of control was found to be a dominant factor correlating not only with their own perceived alliance but with patients’ perceived alliance as well.

Indeed, the literature acknowledges the contribution of locus of control to perceived dyadic relationships (Kent et al. Reference Kent, Matthews and White1984; Kinicki and Vecchio Reference Kinicki and Vecchio1994; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Thomas and Charles2005; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Lefcourt and Holmes1986; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Tomlinson and Noe2010), and our findings support the hypothesis that locus of control also makes a contribution, specifically, in the context of the patient–oncologist dyad. As was predicted, oncologists who perceived event causality as being controlled by their own actions experienced a better alliance with their patients than did those who believed in chance or faith, the latter of whom perceived their patient–oncologist relationships to be less mutual and more distant. This finding might be explained by previous research, suggesting that a higher sense of personal control over one’s outcomes contributes to being better attuned to others and to being more collaborative and proactive in creating and preserving relationships (Langer Reference Langer1975; Noe Reference Noe1988; Parker and Price Reference Parker and Price1994; Turban and Dougherty Reference Turban and Dougherty1994; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Tomlinson and Noe2010). By the same token, a lack of sense of control has been found to be related to hopelessness and feelings of apathy (Gale et al. Reference Gale, Hatch and Batty2009; Skinner Reference Skinner1996; Taylor Reference Taylor1989), as well as to passive and avoidant behaviors (Blanchard-Fields Reference Blanchard-Fields2007; Brosschot et al. Reference Brosschot, Gebhardt and Godaert1994; Crandall and Crandall Reference Crandall, Crandall and Lefcourt2013; Lefcourt Reference Lefcourt1981), leading to reduced intimacy, closeness, and trust in a relationship. Unexpectedly, no similar associations were found among patients. This interesting non-significance requires future study. In sum, oncologists’ ability to establish a good and caring alliance with their patients seems to be related to their perceiving their own actions – including the oncological care they provide – as influential.

An important finding revealed a partner effect that indicated an association between oncologists’ internal locus of control and patients’ working alliance. It is especially interesting to notice this cross-impact due to the fact that no correlation was found between patients’ locus of control and their own perceived working alliance. A plausible explanation for this finding is that when oncologists with a high internal locus of control experience themselves as powerful and influential, they may also be perceived by patients as confident, motivated, and sensitive to the patients’ needs and preferences. This perception might increase patients’ trust and confidence in their oncologists and provide them with a sense of security and control in their lives. As a result, an emotional bond may begin to develop between patients and oncologists, promoting patients’ cooperation and shared decision-making (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Zimmermann and Rodin2005; Thompson and Ciechanowski Reference Thompson and Ciechanowski2003). This collaborative aspect of the relationship corresponds with person-centered care, the aim of which is to treat people rather than illnesses and to encourage patient involvement in treatment and shared decision-making (Anderson Reference Anderson2002; Christensen and Johnson Reference Christensen and Johnson2002; Engel Reference Engel1977; Holman and Lorig Reference Holman and Lorig2000; Laine and Davidoff Reference Laine and Davidoff1996; Little et al. Reference Little, Everitt and Williamson2001; McLane et al. Reference McLane, Zyzanski and Flocke1995; Putnam and Lipkin Reference Putnam and Lipkin1995). Patient-centered care has also been found to promote treatment quality and outcomes (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Daughtridge and Sloane2002; DiMatteo and Lepper Reference DiMatteo, Lepper, Jackson and Durn1998; Kjeken et al. Reference Kjeken, Dagfinrud and Mowinckel2006; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Glasgow and Davis2001). The significant partner effect that was found in the current study underscores and reinforces the oncologist’s impact on the dyadic relationship, a topic that has been neglected to some extent in this field of research. The clinical implications of the findings include identifying and promoting oncologists’ sense of control and self-efficacy; doing so might improve the patient–oncologist relational bond and enhance collaboration and shared decision-making.

The current study results also point to the role of oncologists’ age and years of experience in their locus of control and working alliance. Older oncologists and those with more experience tended to report higher levels of internal locus of control, meaning that they felt their actions had a greater influence on their own life events. It may be that their many years of experience gave them more confidence, and despite their daily exposure to the uncontrolled nature of events, they were still able to feel that their actions had an influence on their patients’ conditions. Another possible explanation for the positive association between age and working alliance may be that older people tend not to be overly upset when faced with socio-emotional problems and interpersonal conflicts, and may therefore perceive the relationship in a more positive way (Charles and Carstensen Reference Charles and Carstensen2008). These results are important and highlight the need for further investigation of the effect of experience and age on oncologists’ perception of internal and personal control in the face of coping with an uncontrolled reality. Moreover, the results emphasize the need for interventions mainly for younger and less experienced oncologists, especially when considering the positive influence of oncologists’ internal locus of control on oncologists’ and patients’ perception of their working alliance.

An interesting finding worthy of notice was that personal characteristics were found to be more significant in terms of patient–oncologist working alliance perceptions than were clinical factors such as cancer type, time since diagnosis, or stage of disease. This finding implies the importance of personal characteristics in working alliance perceptions and requires further research.

Some limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. First, the IPC questionnaire was found to have only medium reliability for patients and oncologists; as such, to increase its reliability, 2 items were removed. This limitation should be taken into consideration. Second, the current study’s findings were based on cross-sectional data, which preclude causal interpretations. Third, the patient sample was predominantly female (75.7%), and patients’ and oncologists’ gender combinations may have had an impact on working alliance and the relation between working alliance and other variables. Further research is needed in order to examine the working alliance in dyads with different gender combinations. Fourth, the research variables (working alliance and locus of control) were measured via self-report questionnaires; therefore, human subjectivity, bias, and unconscious factors must be taken into account. Fifth, the current study was conducted in a specific sociocultural context (i.e., an Israeli oncological setting). Although Israel could in many ways be characterized as a Western and individualistic society – it is also typified as collectivist and traditional society (Goldzweig et al. Reference Goldzweig, Hasson-Ohayon, Elinger and Breitbart2016) and in the same time is known as questioning and less respecting authority. These factors may color and influence doctor–patient relationships and, as such, the role of culture on the oncologist–patient working alliance is worthy of further investigation. Sixth, a relatively small number of oncologists participated in the study. Finally, an oncologist sample that is more heterogeneous than the one used in the current study might allow for better control of potentially confounding variables, especially regarding oncologists’ gender and experience.

Our study highlights the important role of the oncologist in the patient–oncologist dyadic relationship. Oncologists who perceive event causality as being controlled by their own actions seem to develop a good alliance with their patients and even to influence positively on their patients’ working alliance with them. Our findings represent a small step toward understanding the complex realm of the oncologist–patient relationship. Further research is needed in order to understand the role of variables such as sociocultural environment, illness perception, and cancer-related factors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

S.L. participated in the conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and writing; H.A. participated in the conceptualization and data curation; G.G. participated in the formal analysis and software; I.H.-O. participated in the supervision; M.B. participated in the conceptualization, methodology, writing, and supervision.

Conflicts of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Boards of 2 hospitals: Sheba Medical Center (SMC-19-6019) and Shaare Zedek Medical Center (SZMC-19-0012).

All participants were volunteers and signed informed consent forms before filling out the research questionnaires.