Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is a formalized communication process that “enables individuals to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these goals and preferences with family and health-care providers, and to record and review these preferences if appropriate” (Korfage et al. Reference Korfage, Carreras and Arnfeldt2020, p.3). Clear evidence of the effectiveness of ACP in improving goal concordant care in different patient populations, including cancer, has proved elusive. Research findings are variable, uncertain, and often inconsistent (Jimenez et al. Reference Jimenez, Shin Tan and Virk2018; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Butow and Kerridge2018a; Korfage et al. Reference Korfage, Carreras and Arnfeldt2020; Mackenzie et al. Reference Mackenzie, Smith-Howell and Bomba2018; Morrison Reference Morrison2020; Weathers et al. Reference Weathers, O’Caoimh and Cornally2016).

However, a recent systematic review suggests that ACP could improve the communication about provided care and patients’ wishes among a variety of patient populations, including oncology (Kishino et al. Reference Kishino, Ellis-Smith and Afolabi2022). The field of ACP has changed over time from a legal process – enabling people to refuse prolonged and futile treatment – to a deliberative and communicative process of engaging patients, together with their substitute decision-makers and relatives, in conversations about goals of care, values, preferences, and hopes (Robinson Reference Robinson2012). In such a way, ACP may be conceptualized as a process that goes beyond decisions for future treatment and care, becoming a more complete act of communication among patients, health-care professionals (HCPs), and caregivers (Fried and O’Leary Reference Fried and O’Leary2008; Rietjens et al. Reference Rietjens, Sudore and Connolly2017).

The core of the ACP process seems to reflect an alternative model of autonomy – relational autonomy (Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie2008) – which conceives patient autonomy in a relational context. This perspective is based on the theoretical framework of ethics of care, which highlights the interdependency of human beings and the fundamental importance of their relationships with significant others in shaping and sharing decisions about care. Therefore, any moral choices should be considered within the network of interpersonal relationships from which it originates (De Panfilis et al. Reference De Panfilis, Di Leo and Peruselli2019, Reference De Panfilis, Peruselli and Artioli2021).

Within this model, patients are not able to engage in meaningful participation in ACP unless relational, emotional, and social issues are taken into consideration. ACP has more to do with shared decision-making and communication, as well as relationships and trust, than with planning future care, refusal of medical treatments, liberty, and rights (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Butow and Kerridge2016). A study exploring oncologists’ and palliative care physicians’ understanding of patient autonomy in the decision-making process in end-of-life care (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Butow and Kerridge2018b) provides evidence of the distance between participants’ theoretical accounts about patient autonomy and real clinical practice. Interestingly, relationships were an important topic that arose from this study: oncologists stressed how the relationship they had with the patient played a crucial role in end-of-life care discussions. Thus, the ACP process may be considered as a communicative tool aimed at balancing patient and HCP expectations around care and facilitating the understanding and appraisal of physicians’ recommendations (Hilden et al. Reference Hilden, Honkasalo and Louhiala2006).

In order to convey goals and preferences for end-of-life care, it is necessary to contextualize these communicative acts within the larger set of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that may be shared by family members. Accordingly, Rhee et al. (Reference Rhee, Zwar and Kemp2013) emphasized the bidirectional link between ACP and patient–family relationships: the patient–family relationship affects ACP and ACP affects patient–family relationships. The efficacy of ACP is shaped by the quality and nature of the relational dynamics (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Moorman and Boerner2013; Rhee et al. Reference Rhee, Zwar and Kemp2012). In addition, it is important to note that the way ACP and family relationships interact is not easily predicted. Boerner et al. (Reference Boerner, Carr and Moorman2013) found that emotionally supportive relationships do not uniformly enhance planning, whereas negative relations do not necessarily impede it. Little is known about the impact of the ACP process on patient–family relationships. Kishino et al. (Reference Kishino, Ellis-Smith and Afolabi2022) observe that ACP discussions have the potential to be harmful as well as positive in their effects. However, Rhee et al. (Reference Rhee, Zwar and Kemp2013) found that ACP had a positive impact on the patient’s family. It helped relatives to prepare physically and emotionally in order to more easily cope with stressful future end-of-life situations, to grieve after the death, and to resolve tension and conflict between family members.

Our aim was to further investigate the impact of the ACP process on close relationships through an examination of how an ACP intervention based on structured conversations affects the relationship between patients with advanced cancer and their nominated Personal Representatives (PRs), usually a relative. Focusing on relational issues – in terms of the degree of reciprocal understanding, level of support, and closeness – allows to increase the potential of ACP to support communication and understanding between patients and relatives and to engage in effective communication with professional caregivers.

Methods

The ACTION research project

The ACTION research project aimed to test the effectiveness of an adapted version of the Respecting Choices® (RC) ACP intervention (Detering et al. Reference Detering, Hancock and Reade2010) among patients affected by advanced lung and colorectal cancer through a cluster-randomized trial (Korfage et al. Reference Korfage, Carreras and Arnfeldt2020; Rietjens et al. Reference Rietjens, Korfage and Dunleavy2016).

The ACTION trial was a multicenter cluster-randomized controlled trial in 23 hospitals in 6 European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom). The total number of enrolled patients was 1117 (for details, see Korfage et al. Reference Korfage, Carreras and Arnfeldt2020). The intervention includes 3 main elements (see box I). All ACTION RC ACP intervention materials were drafted in English and translated into the languages of the countries participating in the ACTION trial, in close collaboration with the RC program developers. In this translation process, materials were, where necessary, adapted to local cultural and ethical nuances, while not losing the content, structure, and integrity of the RC ACP-facilitated conversation (Arnfeldt et al. Reference Arnfeldt, Groenvold and Johnsen2022; Korfage et al. Reference Korfage, Carreras and Arnfeldt2020).

Within the ACTION research project, a qualitative study was conducted in 4 countries (Italy, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Slovenia) to explore the lived experience of engagement with the ACTION RC ACP intervention from the perspectives of patients, their PRs, health-care providers, and RC facilitators (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Bulli and Caswell2022). For this study, patients were recruited using the same eligibility criteria as for the trial (see box II).

Patients and their PRs – defined as the persons chosen by the patient to express their preferences – were invited to take part in the qualitative study arranging a first research interview within 2 weeks of completing the RC intervention and a follow-up research interview 10–14 weeks later. Patients and PRs could participate in the interviews separately or together. Each research interview lasted approximately 1 hour and was carried out in a private room in hospital or at home. The topics discussed in each of these interviews are shown in box III. The intervention and the research interviews, both with patients and PRs, were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data collection

The lead authors of this paper had access to the content of all Italian and UK case studies (n = 10) including RC conversations (n = 13) and research interviews with patients and PRs (n = 21). In addition, complete transcripts from one Dutch and one Slovenian case study, which had been translated into English, were available: a further 2 RC conversations and 4 research interviews. Resources were not available for more extensive translation of the Slovenian and Dutch case data.

All case study data relating to the first completed English and translated Italian cases were “rough” coded by members of the teams from all countries (UK, NL, IT, and SL). Coding was compared, collated, and used as the first iteration of a collaborative coding frame for thematic analysis of the intervention and interview data. This was developed through further comparative work on single cases from Italy, Slovenia, and the Netherlands, which were translated into English. One member (M.Z.) of the qualitative study undertook the task of synthesizing initial coding into a single framework, which was then used as the basis of coding the remaining case studies which the teams undertook in their own language. Each team then developed the analysis and coding frame through working on their national patient cases. In addition, a detailed narrative summary of each case was written in English using a template developed from the first UK case. This included translated extracts from the interventions and interview transcripts. Further input and additional data, including translated extracts, from each team were provided during the process of review and redrafting of the paper. For the remaining Dutch and Slovenian cases (n = 8), the national research teams extracted and translated relevant extracts from the data relating specifically to the topic.

Data analysis

We followed a phenomenological approach (Creswell Reference Creswell1998; Giorgi Reference Giorgi2018; Moustakas Reference Moustakas1994) aimed at identifying the meaning of the lived experiences for participants about the RC ACP intervention. An in-depth qualitative analysis was undertaken by members of the Italian team (F.B., G.M., and A.T.). Relevant meaning units were identified in each transcript and across case studies. Eventually, after carefully reading reading and comparison, a structural reading of the data was developed (Moustakas Reference Moustakas1994).

The quotations reported in the results section are identified according to the following code: country (ITA, UK, SLO, and NL), case number, patient (P) or PR, first or second RC conversation (RC1 or RC2), and first or second research interview (int1 or int2).

Results

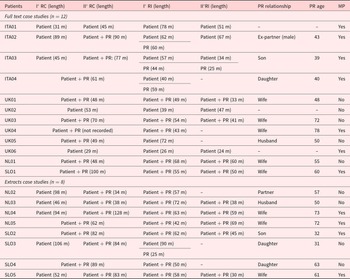

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 20 patients enrolled in the qualitative study are presented in Table 1. Age of the patients ranged between 50 and 88 years (mean 66.3; SD 11.8), 15 patients were married, 11 were male, all but 2 had children, and 4 patients had colorectal cancer. ACTION RC ACP conversations lasted 29–106 minutes (mean 62.5; SD 28.4) when the PR was not engaged in the conversation and 34–128 minutes (mean 71.4; SD 25.1) when the PR was present. In 3 cases, no PR had been engaged in the ACTION RC ACP intervention. In 4 cases, the nominated PRs were sons; in only 1 case, the PR was not a relative. Patient cases for whom the complete data set was available to the lead authors (F.B., G.M., and A.T.) are detailed in Table 2. Analysis of these cases was supplemented by data extracts from the remaining patients.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients enrolled in the qualitative study

Table 2. Length of RC conversations and research interviews (RI), PR characteristics and compilation of the My Preference form (MP), differentiating full text, and extracts case studies

RC: respecting choices conversation; RI: research interview; MP: my preference form; length in minutes (m).

When columns I° RC and II° RC are joined, it means that the RC intervention was undertaken in a single conversation.

The main themes that emerged from our analysis are that (1) ACP can provide an opportunity to strengthen relationships between patients and their PRs (2) through the potential realigning of their understanding and expectations about the illness condition and its evolution.

ACP: An opportunity to overcome obstacles in communication between patient and PR

Cancer provokes a significant change in patients’ lives in terms of priorities, values, and relationships. “When it [the disease] happens to you, you see it in a completely different way. At least I find it sad. To be in a situation where you have to change completely. You have to reset yourself and reload […] Your perspective changes” (SLO1 P int1). The ACP process opens up new opportunities for people going through such difficult moments. Indeed, the ACTION RC ACP intervention provided participants with an opportunity to explore, reflect upon, and discuss their goals, values, and beliefs for future treatment and care together with their PRs. It was experienced as an approach that facilitated the occurrence of communicative acts between patients and their PRs. “It can’t be done without a conversation. We always try to find a compromise. You can’t make a decision on your own. Talking, talking…” (SLO5 PR RC).

Some conversations were experienced as profound and challenging “…even talking about them [the preferences for last stages of life] is an unpleasant thing, because one thing is talking about these topics during a healthy situation, another thing is talking about it in an illness situation, it is completely different” (ITA2 P int2). In some cases, people refer to not being confident in managing their emotions within close relationships before taking part in the RC ACP intervention, because they feared to elicit suffering of their loved ones. “We had talked about it. I had made the speech at home, but then he always said: ‘Mum, just stop, when it arrives you will see’ … The speech was possible here in this room [meaning the ACP intervention discussion] because at home he always stopped me” (ITA3 P int1).

The ACTION RC ACP intervention was facilitated by a trained facilitator, usually a HCP who promoted the communicative acts between people participating in the process. “It is not that she [the facilitator] was there to collect the answers aseptically […otherwise] it might become a meaningless bloodbath…” (ITA4 PR int1). Moreover, the facilitator was able to encourage family members to communicate with each other, overcoming emotional barriers. “I was pleased […], we’ll do it, because you’ve got someone else out of the family that you can turn to, sort of thing, you know, speak to” (UK4 PR int2).

Realigning: the potential impact of ACP process

The ACP process involves more complex communicative acts than the simple giving of information and documenting patient preferences for future care. In some cases, deeply sharing about such personal and urgent issues as approaching death may have had an impact on the relationship between patients and PRs. Indeed, participants’ accounts revealed a realignment between patients’ and PRs’ understanding and expectations about the illness condition and its evolution: “[…]it’s like, not the pushing things away […] it’s preparing your mind set, really, so yeah, it was useful” (UK1 PR int1); “But now, having had that conversation, it’s kind of, makes me more aware […] I’ve become certainly more realistic about things” (UK1 PR int2).

The process of realigning patients’ and PRs’ understanding seems to allow the discussion of critical issues concerning the last stages of life which evoke intimate emotions: “The tears have to come out” (SLO1 PR int2); “Yes, at one point we discussed his death … and I am still having difficulty coming to terms with it. I am living on a black cloud, normally you would live on a pink cloud … but I can’t really get to grips with it yet” (NL1 PR int1); “It makes you get older to hear words like these […] because you imagine him in a condition in which he is no longer able to be the father you have always had” (ITA4 PR int1).

This emotionally activating “sharing process” seemed to have the potential to make the relationship between patient and PR closer. Indeed, in one case, we noticed a reluctance to share emotions before engaging in the ACP process: the patient avoided talking freely about her intimate experiences and concerns related to the disease with the whole family in order to protect them all from suffering. However, participating together with her son in the ACP process was a kind of liberation “[it] frees you from everything” (ITA3 P int1,2). After the ACTION RC ACP intervention, the patient explicitly reported that her son had begun to behave in accordance with her wishes and that he finally grew up, making their relationship stronger “At present he talks more than previously, he is much more open with me, he asks me if I had my blood pressure measured, if I ate something, while before he did not ask anything to me.” (ITA3 P int1).

We observed something similar in another case where the patient and his wife began to discuss topics they would not have otherwise, sharing vulnerable feelings and thoughts related to his illness. “Yes, it [the intervention] freed us. I said if you want the best for me, don’t cry. But we didn’t talk. After the [RC] conversation, we started talking” (SLO1, P int2). The patient’s wife confirmed this: “The tears have to come out. It’s a lot easier now that we talk openly. We’re not hiding anything. It feels good to talk” (SLO1, PR int2). This made them “even closer.” “Even before that, we were very close. Now, we are even closer. What we need the most is each other.” (SLO1, PR int1). “He’s handling everything well. I think it will be ok. If they prolong his life for a few years, we’ll be happy. To go to sleep and wake up together… it’s the most beautiful thing, truly. You can really appreciate it, even more.” (SLO1, PR int2).

The data indicate the potential for ACP discussions to result in a shared understanding between patients and their PRs and a strengthening of their relationship and mutual commitment. However, this was not always apparent, and in some cases, it seemed that the ACP intervention could spark conflict and disagreement. For instance, this happened in a case where the patient chose as PR someone who had previously been her fiancé for 12 years. Although their romantic relationship ended a few years before taking part in the ACTION RC ACP intervention, the patient had no doubts in choosing her PR, given their deep and trusting friendship. They had discussed several times what their wishes and preferences were for future treatment and care, and she had been always reassured that her preferences would have been followed. However, when the patient reflected on the ACP intervention in her research interview, she expressed the thought that in the event, a ready agreement by her ex fiancé to the comfort care she had specified as her preference, rather than the option of active care to prolong her life, would constitute an expression of her low worth to him, rather than his respect for her wishes. “It had struck me when he [the PR] had said, when the facilitator had asked him whether he would surely have done what I had said to do, even if he would not have agreed … And he said yes, he felt so calm and secure […] I thought in general that one might have doubts, puzzlements and uncertainties […] And this thing had struck me very much” (ITA2 P int1). The patient reported that she and her PR had quarreled between the first and second research interviews, and their friendship was ended. The patient herself questioned whether the ACP RC intervention might have caused the interrupting of the relationship between her and the PR: “In that moment it did not seem to me that our relationship had changed … after this thing [the intervention] … but maybe yes, a little bit and probably … I am not able to say if it had influenced or not in interrupting our relationship” (ITA2 P int2). As a result of the broken relationship, the patient suffered a lot: “[…] it’s a lack, it’s a separation, it’s a loss, it’s like when someone dies” (ITA2 P int2).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that taking part in the ACTION RC ACP intervention may impact the relationship between the patients and their PRs by realigning patients’ and PRs’ understanding and expectations about the illness condition and its evolution and strengthening their commitment to each other. This is the desired outcome of a person-centered communication (Epstein and Street Reference Epstein and Street2007), i.e., that specific professional–patient relationship which allows patients to share efficaciously the decision-making process with their doctors.

Given that the ACP process encourages trust and commitment and “sanctions” the interactions through the formalization of choices for future treatment and care, it works like a linguistic performative act. According to Austin (Reference Austin1962), a linguistic performative act means “doing things with words,” as when people get married, testify, or promise something to someone. Austin highlighted that a linguistic performative act requires the fulfillment of a list of “felicity conditions,” among which the full commitment in the process is the most important.

Overall, the results of the study make apparent the potential of the ACP process for opening up a reflective space with the potential to increase awareness of patient and PR perspectives and the reality of the illness (Zwakman et al. Reference Zwakman, Pollock and Bulli2019), while also strengthening bonds between the patient and PR in the present (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Bulli and Caswell2022). Indeed, several patients and their PRs cherished their relationship and aimed at preserving or developing togetherness (a good life together), notwithstanding the difficulties due to illness and treatment and the uncertainties of the future.

For all these reasons, the ACP process may be understood in terms of a model of relational autonomy. Decision-making about future treatment and care involves the patient not only at an individual level but also the involvement of family and friends. Moreover, it has been stressed that relational autonomy in ACP incorporates the fluctuating nature of autonomy in chronic diseases like cancer and the role of vulnerability of the patient, particularly when a life-threatening illness is progressing (Killackey et al. Reference Killackey, Peter and Maciver2020). Our results, limited to the relationship between the patient and PR, support this model, highlighting the importance of the relational context surrounding the patient. However, choosing the PR on the basis of the most supportive relationship does not necessarily result in a positive ACP process (Boerner et al. Reference Boerner, Carr and Moorman2013). This is illustrated in the case of the ex-partner who fulfilled all the qualities generally required for the PR in the ACP process but failed to find resonance with the emotional needs of the patient now facing death. Therefore, it is important to recognize how sensitive the ACP process is in reality and how crucial may be the need for skilled facilitation in supporting effective communication about ACP between patients and their relatives, as also Kishino et al. (Reference Kishino, Ellis-Smith and Afolabi2022) highlighted.

Limitations and further research

A first limitation of this study concerns the limited period of follow-up observations and the focus on the PR only. Furthermore, the significance of the relationship between patients and PRs (being a partner, or a child, or friend) was not explored. Future research should investigate this topic through a longer follow-up and post-bereavement interview to explore whether any other changes happened concurrently in the wider relational context of the patient and the potential relevance of the relationship between patients and PRs.

A second relevant limitation was the language barrier, given that the fluency in a native language is critical in a phenomenological study. Moreover, the limited resources for translation restricted the access of team members to all primary data.

Further research is required to confirm and extend the results of the study findings.

Strengths

A strength of the study is its international nature with a shared methodology. It was especially valuable to have access to the transcripts of the ACTION RC ACP discussions between the patient, PR, and facilitator and to be able to compare these with subsequent interview data. In addition, the study involved a careful development and translation process to ensure cross cultural adaptation of materials and data analysis within each of the participating countries.

Conclusion

ACP is a dynamic interplay between patients, family members, and HCPs, which goes beyond the expression of a patient’s choice for future treatment and care. We suggest that a significant consequence of the ACP intervention may be to strengthen the relationship and mutual understanding between some patients and their PRs and to enhance their sense of mutuality and connectedness in the present.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951523000482.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the qualitative study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) in the coordinating center at Erasmus MC (NL50012.078.14, v02) and in all participating countries. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to entry to the study.