Introduction

Wildlife crime has captured the attention of governmental and nongovernmental organizations, academics, and practitioners from conservation to criminology. There is increasing awareness that the impacts of wildlife crime extend beyond biodiversity loss and are a significant threat to human economies, security, subsistence and well-being (Brashares et al., Reference Brashares, Abrahms, Fiorella, Golden, Hojnowski and Marsh2014; Gore et al., Reference Gore, Braszak, Brown, Cassey, Duffy and Fisher2019). The growing literature on wildlife crimes (which can include poaching, trade, trafficking, and/or possession) provides new knowledge for addressing illegal activities and protection of species, with the last decade marking an increase in theoretical and methodological applications from criminology. Research on wildlife crime is becoming increasingly nuanced and interdisciplinary, with advances in understanding wildlife crime offenders (e.g. Phelps et al., Reference Phelps, Biggs and Webb2016), applications of situational crime prevention (e.g. Petrossian, Reference Petrossian2015) and engaging communities in wildlife crime prevention (e.g. Anagnostou et al., Reference Anagnostou, Mwedde, Roe, Smith, Travers and Baker2020).

Despite this growing attention, more research into the direct and indirect roles women play as offenders, protectors and victims is needed to broaden our understanding of wildlife crime and protect biodiversity. Our aim here was to use the extant criminology and conservation literature to identify key gaps in research and relevant typologies and frameworks informed by criminology to structure future research on women as offenders, protectors (handlers, managers, guardians) and victims of wildlife crime. We begin by clarifying our terms when discussing gender, followed by context for our assertion based on an exploratory review of the peer-reviewed literature, and contrast this with results found from a search of news articles.

Gender is an explanatory factor in multiple dimensions of wildlife conservation, including women's access to and participation in conservation programmes (e.g. Rinkus et al., Reference Rinkus, da Cal Seixas and Dobson2017). Yet survey-based research on wildlife crime often fails to report the gender identity (man/woman) of the sample, often reporting offenders as ‘villagers’ or ‘community members’. By gender, we are referring to the social and cultural aspects of the lived experiences of men and women. Gender interacts with, but is separate from biological sex, and can be studied from multiple angles including, for example, gender identity, gender roles, gendered power dynamics, and gender-based relationships. We use ‘gender identity’ here instead of ‘sex’ because how people identify may or may not be related to their biological sex, and how others perceive gender identity can influence the gendered nature of relationships. Furthermore, it is unlikely that researchers ask participants to disclose their biological sex, nor is biological sex necessarily a determinant for gender identity.

To examine the gaps in the conservation literature with respect to gender as it relates to wildlife crime, we conducted an exploratory search in the Web of Science database for January 1990–March 2020. Of the 261 results returned for the search term ‘wildlife crime’ only two remained after further filtering for ‘gender’. Similar results were found using the search terms, ‘wildlife poach*’ (101 total, one after filtering for ‘gender’, but not relevant), ‘illegal hunt*’ (880 total, six after filtering for ‘gender’, only four relevant), and ‘illegal fish*’ (1,055 total, 10 after filtering for ‘gender’). When using ‘women’ as a filter in place of ‘gender’ few results were found. This indicates that < 1% of articles addressing wildlife crime mention the gender identity of those involved in wildlife crime or consider gender as an integral part of the research.

Despite the paucity of peer-reviewed literature on this subject, technical reports and news articles point to the involvement of women in various aspects of wildlife crime. We searched the NexisUni database for news articles using the terms ‘wildlife crime’ and ‘women’, resulting in 168 articles (after the removal of duplicates) for March 2015–March 2020. Fifty-nine per cent (99) of these reported women as offenders, 26% (44) discussed women in some type of guardianship or protection role, and 15% (25) presented instances in which women were victims of wildlife crime and related consequences. These articles ranged from high-profile news such as the so-called Queen of Ivory, a woman arrested for smuggling 860 elephant tusks (Tremblay, Reference Tremblay2019), to documenting the involvement of women in everyday wildlife crime, such as a woman smuggling star tortoises in India (Salunke & Chatterjee, Reference Salunke and Chatterjee2018). Key technical reports have also discussed the involvement of and implications for women in wildlife crime (e.g. Booker & Roe, Reference Booker and Roe2017; Hübschle & Shearing, Reference Hübschle and Shearing2018).

Our exploratory search illustrates the varied involvement of women in wildlife crime globally and within the fisheries, forestry, and wildlife conservation sectors. Here we discuss some of the underlying assumptions and historical and contemporary biases that may have led to the dearth of gender-based research on wildlife crime. We focus specifically on women, although we advocate for a gendered analysis of wildlife crime more broadly in peer-reviewed and empirical research. Future research should consider how power and patriarchy influence the involvement of men and women in wildlife crime, and the impacts of wildlife crime, and responses and interventions, on gender relations.

Leveraging the criminology literature

Research in criminology mirrors what we see in other social sciences, including the human dimensions of natural resources, in the lingering effects of a historical and overt gender bias towards men as a subject of study and theory formation (e.g. Kruttschnitt, Reference Kruttschnitt2013; Hübschle, Reference Hübschle2014). Additionally, despite some exceptions (e.g. the study of human trafficking by West African women) the majority of the literature that investigates women's pathways to offending and typologies of female offenders is based on the Global North (e.g. Dehart, Reference DeHart2018; Barlow & Weare, Reference Barlow and Weare2019). Regardless of past and present biases, criminology provides us with the most methodologically and theoretically robust understanding of women's deviant or criminal behaviour. There are numerous theories of crime causation, a review of which is beyond the scope of this study. However, opportunity-based theories of crime have been applied in multiple contexts to understand wildlife crimes affecting fisheries, forestry and wildlife resources (e.g. Petrossian, Reference Petrossian2015). At their core, opportunity theories focus on three groups of actors (offenders, protectors as guardians, handlers and managers, and victims/targets), and how they interact within space and time to create opportunities for crime and crime intervention. We centre our discussion on offenders, protectors and victims, to address the significant gap regarding the study of women in wildlife crime.

To identify frameworks for robust enquiry into the varied roles of women in wildlife crime, we turned to the criminology literature associated with gender and offending, policing and guardianship (i.e. willingness to intervene), and victimization. For the purpose of this study we define wildlife as non-domesticated flora and vertebrate fauna of aquatic or terrestrial origin, primarily within the fisheries, forestry and wildlife literatures. To anchor our discussion of women as offenders we used Phelps et al.'s (Reference Phelps, Biggs and Webb2016) typology of key actor roles along illegal wildlife trade market chains. This typology was chosen as it reflects a generalized market chain and actor model informed by review of multiple studies across various geographical contexts and wildlife taxa (Phelps et al., Reference Phelps, Biggs and Webb2016). Considerations of women as wildlife protectors draw on what we know about women in formal (police, rangers) and informal (community monitors, citizens) guardianship roles in criminology and conservation. Lastly, to anchor our discussion of women as victims of wildlife crimes, we use Cao & Wyatt's (Reference Cao and Wyatt2016) conceptual framework for examining green victimization, adapted from the United Nations Development Program (1994).

Offenders

The wildlife crime literature is dominated by research to understand offenders, with a heavy focus on poaching and harvesting of wildlife. However, few articles indicate the gender identity of those involved in wildlife crime and fewer still focus on gender or gendered relations as an important lens through which to understand such illegal activities (McElwee, Reference Mcelwee, Cruz-Torres and McElwee2012). Masculine behaviour, such as exertion of power, gambling and sport, can be motivators for offending (Nurse, Reference Nurse2011). Fabinyi (Reference Fabinyi2012) found masculinity, risk and economic gain to be important factors for men's involvement in illegal fishing. Similarly, McElwee (Reference Mcelwee, Cruz-Torres and McElwee2012) reported that men were more often involved in aspects of illegal wildlife trade when there was greater potential for danger and a need for bribes to customs officials, police and forest rangers, who are often men. In certain cultural contexts, the hunting of wild animals and consumption of wild meat is primarily viewed as a masculine endeavour (Edderai & Dame, Reference Edderai and Dame2006; Lowassa et al., Reference Lowassa, Tadie and Fischer2012; McElwee, Reference Mcelwee, Cruz-Torres and McElwee2012; Sollund, Reference Sollund2020), and cultural taboos can prohibit women from participating in these activities.

Empirical investigations have indicated that men are more likely to be the perpetrator of non-environmental (e.g. Kruttschnitt, Reference Kruttschnitt2013) and wildlife-associated crimes (Sollund, Reference Sollund2020). However, there is evidence that women are also involved in wildlife crime (e.g. Hübschle, Reference Hübschle2014; Agu & Gore, Reference Agu and Gore2020). Furthermore, there is evidence in criminology that the gender gap in crime statistics is influenced, although not completely explained, by the differential targeting of men by law enforcement (e.g. Kruttschnitt, Reference Kruttschnitt2013) and this may extend to conservation. For example, suspicions have been voiced by rangers in Murchison Falls Protected Area, Uganda, that women often had knowledge of and participated in wildlife crimes precisely because they were less likely than men to be suspected and therefore not subject to enforcement (Anagnostou et al., Reference Anagnostou, Mwedde, Roe, Smith, Travers and Baker2020).

An exploration of the peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed literature indicates there is more evidence for women serving as intermediaries, such as processors or vendors, or consumers, than as harvesters (Table 1). We assigned theoretical roles to give examples of peer-reviewed or non-peer-reviewed literature that does not specify the gender of the offender, but where the plausible involvement of women is posited. For example, Harper et al. (Reference Harper, Zeller, Hauzer, Pauly and Sumaila2013) described the paucity of research and consideration of women in the fisheries sector, but did not discuss women within the context of illegal fisheries. Theoretical roles are used to represent five of the eight harvester types, one of seven intermediary categories, and four of the 10 consumer categories (Table 1), indicating areas of potential future research on women's involvement in wildlife crime. However, there are also gaps in knowledge regarding the involvement of men. For example, there is little literature on the prevalence and behaviour of opportunist, local guides and bycatch harvesters regardless of gender.

Table 1 The typology of Phelps et al. (Reference Phelps, Biggs and Webb2016) for key actor roles in wildlife crimes, with examples from peer-reviewed (P), non-peer reviewed (N) and theoretical (T) sources. The designation ‘theoretical’ was assigned to peer-reviewed or non-peer reviewed literature that did not specify gender but where the involvement of women was theoretically plausible.

Although women are not often directly involved in bushmeat hunting, they have been found to encourage it (Lowassa et al., Reference Lowassa, Tadie and Fischer2012) and comprise the majority of bushmeat traders (Edderai & Dame, Reference Edderai and Dame2006) in parts of Africa. Similarities can be seen in both legal and illegal fishing, where women are more likely to be fish processors, traders and retailers (also known as fishmongers, a term that is traditionally reserved for women; Turgo, Reference Turgo2015), and only occasionally involved in illegal fishing (Medard, Reference Medard2012). Aside from studies that have discussed women's involvement in illegal fishing (Medard, Reference Medard2012) and alluded to the illegal harvesting of sea turtle eggs (Madrigal-Ballestero & Jurado, Reference Madrigal-Ballestero and Jurado2017), news articles indicate more frequent and occasional high-profile examples of organized criminal behaviour, with numerous examples of women's involvement as intermediaries in more localized markets such as the trade of bushmeat and freshwater fish (Table 1).

The pathways to offending for women and girls emphasize their unique set of risks, which can lead to offending or escalations of delinquent behaviour (Dehart, Reference DeHart2018). Socio-cultural differences, such as gender hierarchies and gendered roles in labour and economic markets, and how romantic, familial or personal relationships with co-offenders can facilitate the entry of women into crime are probably also relevant in understanding women's involvement in wildlife crimes (Barlow & Weare, Reference Barlow and Weare2019). For example, in the illicit rhinoceros horn markets of South Africa, Vietnamese sex workers were used as bogus hunters, and South African women co-offended as industry insiders with their partners to facilitate this lucrative and organized trade (Hübschle, Reference Hübschle2014). This highlights the need to consider the nuances between co-offending, the unique pathways of women to offending, and the complex relationship between offending and victimization associated with wildlife crime.

Protectors

For the purpose of clarity, we refer to individuals that may intervene and stop crime collectively as protectors. Protectors include handlers that can serve to influence or control the offender (e.g. a parent), managers that are responsible for protecting a physical space (e.g. park manager), and guardians that protect the target or victim (e.g. park ranger). Guardians may have formal, officially assigned, responsibilities to intervene, or may act in a voluntary or informal role. Police officers and park rangers are examples of formal guardians, whereas the public through individual bystander interventions (e.g. wildlife tourists) and volunteer opportunities (e.g. community watch groups) comprise the informal guardian sector. Literature on styles of policing and police officers' decision-making (formal guardians) is abundant, although there is a historical lack of attention to how gender affects officers’ attitudes, philosophy and style of policing (DeJong, Reference Dejong, Miller, Renzetti and Gover2012). Additionally, research shows strong relationships between masculinity and police culture historically, contemporarily and across cultures, despite the fact that the majority (c. 80%) of police work resembles social work (e.g. conflict mediation) rather than physical crime fighting (Chu, Reference Chu2018). Findings associated with the effectiveness, decision-making and policing style preference, such as use of force, by gender are also mixed (DeJong, Reference Dejong, Miller, Renzetti and Gover2012). Additionally, it is likely that the receptiveness of men to women as law enforcement colleagues (e.g. Chu, Reference Chu2018) and the prevalence of women in law enforcement and supervisory roles (e.g. Luna-Firebaugh, Reference Luna-Firebaugh2002) is culturally and contextually variable.

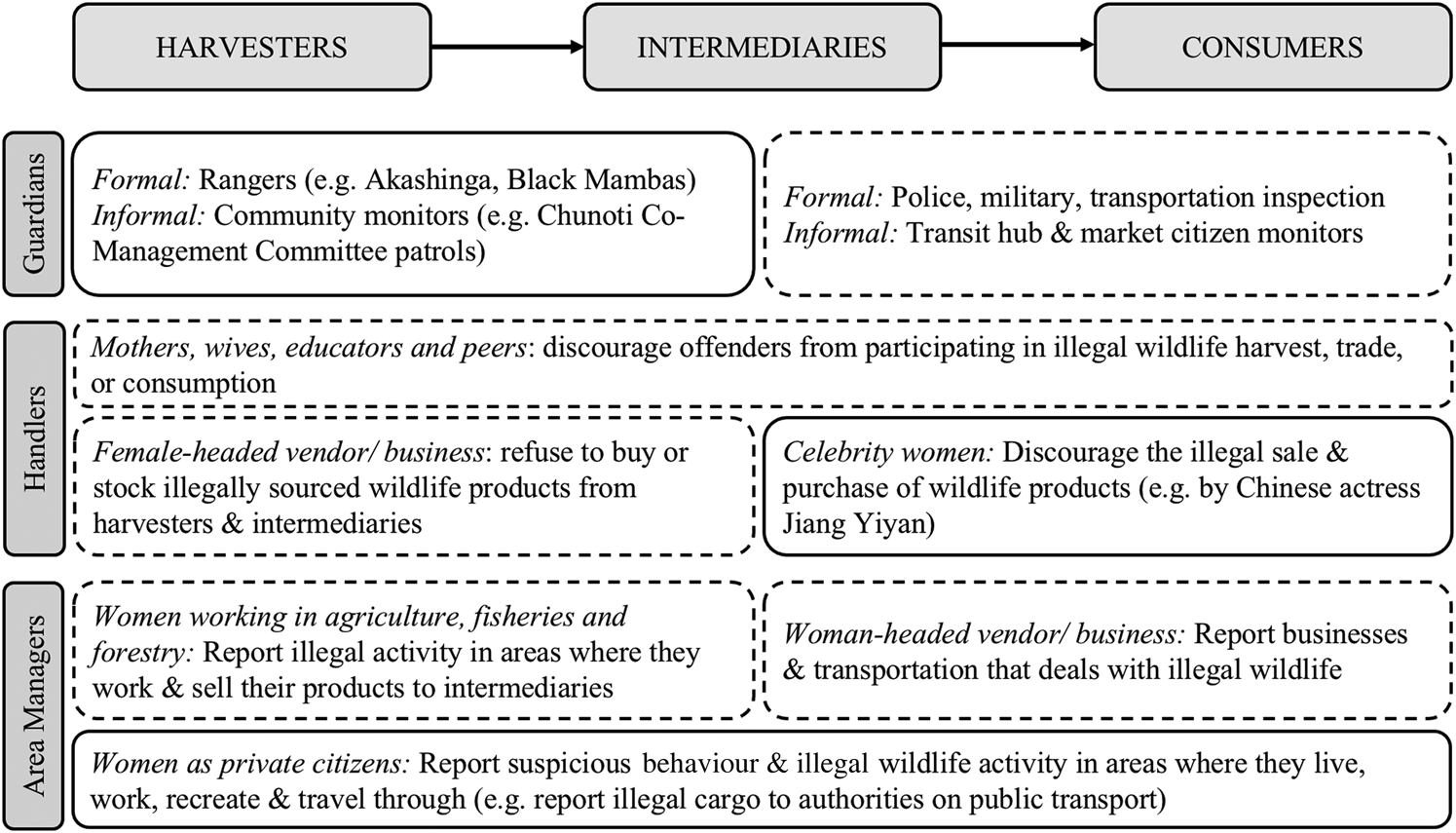

Peer-reviewed literature on women as formal wildlife protectors is scant, with the best sources of information being organizational reports, websites and news outlets. Until recently, criminologists paid little attention to wildlife-relevant police and policing, with notable exceptions, including understanding ranger motivations (Moreto et al., Reference Moreto, Gau, Paoline, Singh, Belecky and Long2019) and misconduct (Moreto et al., Reference Moreto, Brunson and Braga2015). However, Moreto et al. (Reference Moreto, Gau, Paoline, Singh, Belecky and Long2019) pointed out that given the majority of respondents in their Asian ranger study were men, conclusions could not be made as to the effect of gender on motivations for becoming a ranger, suggesting an area of potential future research. There are increasing opportunities for women to serve in formal guardian roles across the illicit market chain (Fig. 1). For example, the Akashinga (Zimbabwe) and Black Mambas (South Africa) are all-women ranger units that have achieved international acclaim. These units comprise rural women and in the case of the Akashinga often single mothers, survivors of abuse, widows or orphans. However, ethical questions regarding the risks (e.g. the Black Mambas are unarmed), the direct and indirect benefits to communities, short and long-term efficacy (Hübschle & Shearing, Reference Hübschle and Shearing2018), and understanding these women's motivations, policing style, use of force, and conduct or misconduct remain unanswered. Theoretically, women serving in mainstream police departments, the military or as inspectors for customs and border patrol, can disrupt intermediaries and consumers of illegally sourced wildlife (Fig. 1). To the best of our knowledge, there has been no research on police, military, border or custom agents as it relates to their roles, attitudes and decision-making associated with wildlife crime-related offences, regardless of gender.

Fig. 1 Demonstrated (solid lines) and theoretical (dashed lines) roles for women as protectors based on their opportunity to disrupt wildlife crime among Phelps et al.'s (Reference Obour, Amankwaa and Asare2016) typology of key actors in the illegal wildlife trade (Table 1).

There has also been limited conservation research on bystander intervention and reporting associated with wildlife crimes. A review of criminology research on bystander intervention in non-environmental crimes reported mixed results for gender as an explanatory factor, depending on the nature of the incident, degree of risk to the intervener, type of intervening behaviour, and urgency of the situation (Leavitt et al., Reference Leavitt, Wodahl and Schweitzer2020). In terms of wildlife crime, Leavitt et al. (Reference Leavitt, Wodahl and Schweitzer2020) explored the willingness of citizens in the western USA to call poaching hotlines and found that few demographic characteristics, including gender, were influential. However, they found that willingness to report was influenced by socio-economic situation, with those that were struggling economically less likely to report poaching. This highlights the importance of attending to the intersectionality of gender. Booker & Roe (Reference Booker and Roe2017) reviewed the effectiveness of communities in reducing illegal wildlife trade and reported on volunteer patrol teams consisting largely of Bangladeshi women, sometimes referred to as ‘the sari squad’, in the Chunoti Wildlife Sanctuary. Evidence of their effectiveness is anecdotal but observational reports claim an increase in the number of elephants in the Sanctuary. The International Fund for Animal Welfare Female Engagement Teams among the Maasai in Kenya support wildlife security by treating women as valuable sources of information, while also providing participants with education on animal behaviour and support for income generating activities. Although this is only a 2-year pilot programme with limited evidence, it acknowledges the direct and indirect roles women play in wildlife conservation and has exhibited positive results, creating a network of trusted women to whom other women can turn for reporting wildlife crime and welfare (Chiu, Reference Chiu2019).

Victims

Research within criminology associated with the victimization of women has focused on various forms of violence and/or exploitation, such as intimate partner violence and trafficking. Scholars of environmental justice, gender and development, and green criminology have provided insights into categorizing impacts of wildlife crime and the resulting socio-economic and environmental consequences despite the dearth of empirical studies directly related to the victimization of women associated with wildlife crimes. Some scholars have posited links between hegemonic masculinity and wildlife crimes (e.g. Fabinyi, Reference Fabinyi2012; Sollund, Reference Sollund2020), and alleged a theoretical convergence of the illegal trafficking and trade of animals, children and women, based on patriarchal power structures and androcentrism (Sollund, Reference Sollund, South and Brisman2013). Studies in development and environmental justice have also illustrated that women and children are often disproportionately victimized by environmental degradation, harm and crime (e.g. Visvanathan et al., Reference Visvanathan, Duggan, Wiegersma and Nisonoff2011; Sollund, Reference Sollund, South and Brisman2013).

Green criminology, with roots in ecofeminism and environmental racism, among other philosophical orientations, goes beyond criminal victimization (e.g. direct harm as a result of crime) and allows us to explore concepts such as secondary victimization (Davies, Reference Davies2014). This considers harms and impacts beyond those directly involved in the initial criminal event and can include victimization of significant others, bystanders and witnesses by law enforcement responding to an offence (Davies, Reference Davies2014). Cao & Wyatt (Reference Cao and Wyatt2016) proposed an interdisciplinary framework for examining green victimization. Although not specifically centred on the victimization of women, this framework draws on the United Nations Development Program's elements of human security to explore how green or conservation crimes harm people, at an individual and collective level, through impacts on economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community and political security (Cao & Wyatt, Reference Cao and Wyatt2016). This framework therefore provides a systematic and robust blueprint for further empirical studies on the impacts of wildlife crime, and resulting interactions with the criminal justice system, on women (Table 2).

Table 2 Aspects of women's wildlife crime victimization from peer-reviewed (P), non-peer reviewed (N), and theoretical (T) sources, based on Cao & Wyatt's (Reference Cao and Wyatt2016) green victimization conceptual framework.

Although there is limited empirical research on the wildlife crime-related green victimization of women, there are examples in organizational reports and media publications (Table 2). For example, Cao & Wyatt (Reference Cao and Wyatt2016) outline the economic and food security implications of illegal timber trafficking for rural livelihoods and although they do not specifically talk about women, it is likely that women's livelihoods may be diminished as they lose access to food resources, ecosystem services, agricultural implements, building materials, medicines and fuelwood (Table 2). Additionally, studies associated with poaching of rhinoceroses (Ceretotherium simum and Diceros bicornis) in and around South Africa's Kruger National Park provide examples of how increased poaching and the resulting increased militarization has affected the personal and political security of women and their communities (Hübschle, Reference Hübschle2017; Massé et al., Reference Massé, Gardiner, Lubilo and Themba2017; Hübschle & Shearing, Reference Hübschle and Shearing2018). Secondary victimization of women may occur when young men are arrested or killed by law enforcement, leaving widows to tend to fatherless households and mothers without sons (Massé et al., Reference Massé, Gardiner, Lubilo and Themba2017). We would expect this to affect communities, and women directly, on an economic and personal level. Hübschle (Reference Hübschle2017) documented deep concern among mothers and wives about the economic insecurity that may occur following the arrest or death of a breadwinner, the detrimental impacts of poaching on the community, and disparate vulnerability of women and children (Table 2). Theoretically women may also be disproportionately affected by political insecurity generated through increased anti-poaching responses in areas such as Kruger National Park, which have led to further exclusion of local people through so-called green land grabs (Table 2; Hübschle, Reference Hübschle2017).

Furthermore, severe and devastating impacts on the personal and health security of women has been documented in association with wildlife crime and interactions with anti-poaching law enforcement. In 2000, the International Fund for Animal Welfare released a video of Russian police officers illegally trading tiger pelts. An investigation revealed that the smuggling ring was also involved in the trafficking of drugs, alcohol and women (PR Newswire, 2000). Investigations into further evidence of the parallel trafficking of women and wildlife products are warranted. This type of victimization can lead to severe personal consequences, including violence and sexual exploitation. Accusations and verified cases of women being beaten, sexually assaulted and killed by wildlife law enforcement have been reported (Table 2).

Discussion

Gender, as one of the primary social constructs that structures access to resources, and societal power dynamics, needs to be considered by researchers during the design, implementation and interpretation phases of research. Despite the long history and extensive literature of mainstreaming gender and women in development (Visvanathan et al., Reference Visvanathan, Duggan, Wiegersma and Nisonoff2011) and advances made within conservation, our review of the peer-reviewed literature on wildlife crime shows that, to a large extent, women remain a hidden element, with a lack of consideration of gender within wildlife crime analysis. We argue that more research into the direct and indirect roles of women in wildlife crime is needed, to address wildlife crime, protect biodiversity and support social justice in response and planning. The most straightforward path towards this goal is accounting for gender in research design, from simply recording the gender identity of research respondents to increasing efforts to engage women as respondents. Targeted research on gender roles and relationships, and the roles of women specifically, in wildlife crime is also warranted.

Considering the typology of key offender roles in wildlife crimes and relevance to the involvement of men and women, there are many theoretical and practical gaps to be filled, particularly within the areas of harvesting and consumption (Table 1). Conservation researchers need to draw on relevant and criminologically informed typologies (e.g. Phelps et al., Reference Phelps, Biggs and Webb2016) to help them think more robustly and with more nuance about the variety of actors and behaviours involved in wildlife crimes. There are demonstrated links between women as victims and their pathways to offending or co-offending (Barlow & Weare, Reference Barlow and Weare2019). It is therefore important to be cognizant of this and to examine how the intersection of gender, socio-economic status, ethnic or racial affiliations, and education influences the participation of women in wildlife crime (e.g. Kruttschnitt, Reference Kruttschnitt2013). Filling the gap in our knowledge regarding the pathways into wildlife crime for women and their direct and indirect roles could lead to more responsive and effective law enforcement and help ensure that interventions are not biased or disproportionately detrimental to any one gender.

Based on empirical and theoretical evidence there are numerous ways that women fulfil roles as protectors, such as serving as place managers while living and working in spaces shared with wildlife, holding formal and informal roles as rangers or community monitors, and serving as a handler or influencer for familial members that engage in risky wildlife crimes. Peer-reviewed, empirical data on the effectiveness, motivations, conduct and policing styles of women officers and of all-women enforcement units is non-existent, with consequences for individual women, biodiversity conservation, and communities. There are additional gaps in knowledge regarding the roles that women serve in informal guardianship of wildlife. For example, the concept of handlers has received little attention in terms of criminological research (Tillyer & Eck, Reference Tillyer and Eck2011) and is, to our knowledge, completely absent in empirical research in conservation contexts. Handlers are people that use normative control of offenders, with their effectiveness increasing with social closeness and willingness to intervene because of personal investment, among other factors (Tillyer & Eck, Reference Tillyer and Eck2011). It is probable that groups such as the Akashinga and Black Mambas play a hybrid role as protectors and handlers, but research is warranted to clarify how these women protectors function in the areas where they live, work and travel through (Fig. 1).

There is a need for applied research into the victimization, both primary and secondary, of women associated with green and conservation crimes and the resulting law enforcement response. The human security framework proposed by Cao & Wyatt (Reference Cao and Wyatt2016) can guide researchers and practitioners in thinking systematically through the many security implications associated with wildlife crime and responses to it (Table 2). Research from mainstream criminology associated with policing could provide valuable lessons for conservation law enforcement on training that supports the humane and just treatment of suspects, their significant others, and communities, to decrease secondary victimization. Future research should be mindful of coercive practices, in which traffickers use women as mules for illegal wildlife products, similar to the well-documented exploitation of often vulnerable women as drug mules (e.g. Hübschle, Reference Hübschle2014). Additional examples of victimization include the potential relationship between wildlife crime and transactional sex practices, such as the fish-for-sex phenomenon, which have been linked to the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, issues of violence against women, and social exclusion in legal wildlife markets (Béné & Merten, Reference Béné and Merten2008). Overall, we found that women as victims of wildlife crime is a matter that has been least explored in the peer-reviewed or other literature. This is consistent with a systematic review of peer-reviewed literature of women and wildlife trafficking in Africa (Agu & Gore, Reference Agu and Gore2020). There is, therefore, a need for applied research on the victimization of women associated with wildlife crime in a variety of conservation contexts.

We have outlined where future research should focus, with priority questions regarding the roles of women as offenders, protectors and victims. Our review suggests that answers to these unasked questions would improve our understanding of the direct and indirect roles women play in wildlife crime. There is much to be learnt from the criminology literature on discerning the roles, motivations and typology of women offenders, women's involvement in wildlife crime prevention and control, the effects of wildlife crime on women, and how to provide social support, resources and advocacy for victims. Other matters requiring attention relevant to conservation are the application of motivation-based typologies to women offenders, how gender may impact the differential assignment of responsibilities within law enforcement units, and the gendered nature of interactions of women within the criminal justice system (e.g. harsher sentences for crimes contrary to gender norms; Weare, Reference Weare2013).

Drawing on criminology can aid in our understanding of and intervention for women as wildlife offenders, uncover the nuances of and pathways to women's involvement in wildlife crime, and help us understand better the gendered nature of victimization of women by wildlife crimes. Understanding women's roles as guardians or protectors could lead to novel and community-responsive solutions for interventions as well as increased community vigilance and resiliency to wildlife crime. Filling these knowledge gaps associated with women and wildlife crime could lead to recommendations, policy solutions, and directed support and resources to mitigate wildlife crime and provide advocacy for victims.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and feedback. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, or commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Conception, literature search and review, writing: JSK, MAR; identification and review of theoretical models: JSK; search and review of news articles: MAR.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.