The saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus is the largest living crocodilian; it can exceed 6 m in length and weigh over 1 t (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Gusmao and Pechacek2018a). It eats a variety of fish, birds and mammals, including people when the opportunity presents. Attacks on people by saltwater crocodiles > 4 m long are usually fatal (Fukuda et al., Reference Fukuda, Manolis, Saalfeld and Zuur2015). Crocodylus porosus inhabits a wide range of saline and freshwater habitats (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Gusmao and Pechacek2018a) and can undertake long-distance sea voyages (Spennemann, Reference Spennemann2020). The IUCN Red List categorizes the global saltwater crocodile population as Least Concern (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Manolis, Brien, Balaguera-Reina and Isberg2021) because abundant strongholds exist (e.g. Australia), but at a national level some populations (e.g. Thailand, Cambodia) are near extinction.

Timor-Leste gained independence in 2002 after 484 years of foreign rule by Portuguese and Indonesian colonial powers. It comprises 14,919 km2 of largely mountainous land, borders West Timor (Indonesia) and is located c. 450 km north of Australia. Within Timor-Leste C. porosus occurs around the whole coastline, but the size, structure and dynamics of the wild population are poorly known (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Gusmao and Pechacek2018a,Reference Brackhane, Xavier, Gusmao and Fukudab) because no standardized monitoring scheme is in place to inform conservation and management (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Manolis, Brien, Balaguera-Reina and Isberg2021). In eastern Timor-Leste a possibly landlocked C. porosus population exists in Lake Ira Lalaro (Lautém district; Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Xavier, Gusmao and Fukuda2018b).

In Timor-Leste the sacred status (lulik) of saltwater crocodiles goes back to the Lafaek Diak (Good Crocodile) creation myth of the country. Killing or even harming crocodiles is often taboo, even if they attack people (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Trindade, Gusmao and Pechacek2019). There is a reluctance to report attacks, particularly those that are non-fatal, as tradition dictates that victims are being punished for doing something wrong. These traditional values did not stop intense hunting and population depletion by colonial rulers but did underpin social acceptance of the post-independence recovery of wild populations (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Trindade, Gusmao and Pechacek2019).

Human–crocodile conflict has been increasing in Timor-Leste since independence. Sideleau et al. (Reference Sideleau, Edyvane and Britton2016) compiled reports of 45 attacks during 2007–2014 (82% fatal), and Brackhane et al. (Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Gusmao and Pechacek2018a) compiled reports of 130 attacks during 1996–2014, the majority (n = 104) during 2007–2014 (58% fatal). In September/October 2022, 7–8 years after our previous extensive assessment, we opportunistically collected information on both human–crocodile conflict and traditional values in Timor-Leste in seven sukus (villages) and associated waterbodies where human–crocodile conflict occurs. We visited the sukus Bauro, Mehara and Muapitine surrounding Lake Ira Lalaro (Lautém district), suku Uani Uma and lagoon Malai Wai (Viqueque district), suku Clacuc and lagoon Modomahut (Manufahí district) and suku Beco (Cova Lima district; Fig. 1). In suku Suai Loro (Cova Lima district) we could only obtain information on the cultural status of crocodiles. We aimed to add to the available data on attacks and to determine whether the frequency of attacks during 2015–2022 had changed since our previous assessment. We also aimed to assess the degree to which cultural restraints against harming crocodiles were intact.

Fig. 1 The seven sukus in Timor-Leste that we visited in 2022: Suai Loro and Beco (Cova Lima district), Clacuc (Manufahí district), Uani Uma (Viqueque district) and Bauro, Muapitine and Mehara (the three sukus surrounding Lake Ira Lalaro in Lautém district).

As described previously (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Gusmao and Pechacek2018a, Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Trindade, Gusmao and Pechacek2019), we asked the village headman (Xefe Suku), the traditional elder (Lia Nain) and other community members to provide information on attacks, including location, the name, age and activity of the victim and the severity of the incident (fatal vs non-fatal). We visited a victim of a recent crocodile attack in Beco and interviewed a fisherman in Uani Uma who had survived a crocodile attack in 2008, to cross-check the information provided (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Trindade, Gusmao and Pechacek2019). In Suai Loro we participated in a ceremony to honour local crocodiles.

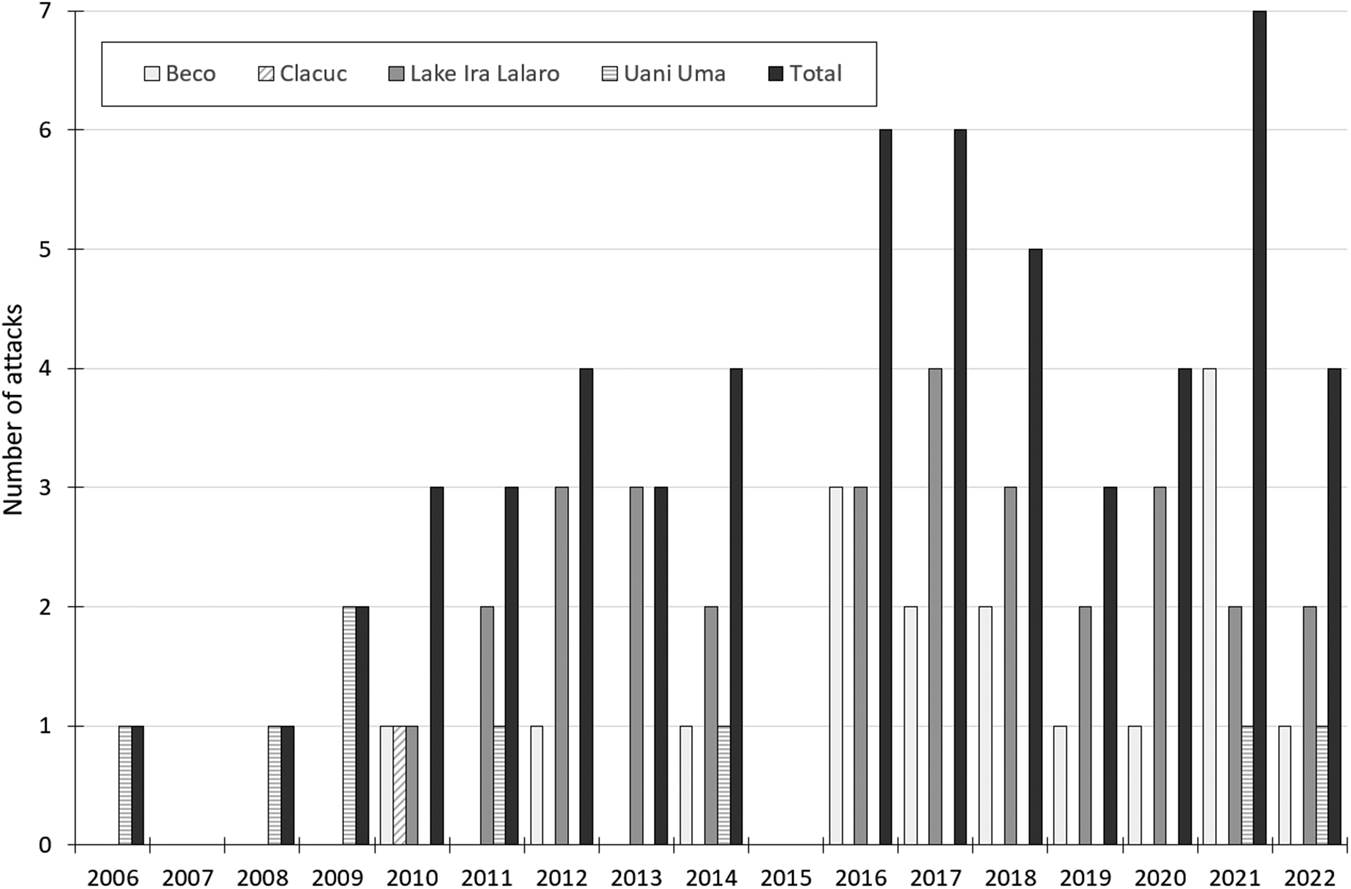

We obtained records of 46 crocodile attacks during 2006–2022 (35% fatal), 35 of which (34% fatal) occurred during 2015–2022 in Lake Ira Lalaro (n = 19), Uani Uma (n = 2) and Beco (n = 14; Fig. 2). None were reported from Clacuc during 2015–2022. The people attacked were mostly men (n = 31; 67%), and most attacks (n = 37; 80%) occurred whilst fishing or collecting mud crabs. Three people were attacked whilst working in rice paddies.

Fig. 2 Saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus attacks from 2006 to 2022 reported to us in the four sites visited during 2022 in Timor-Leste (n = 46; Fig. 1), complemented by attack reports from Brackhane et al. (Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Gusmao and Pechacek2018a; combined n = 56). In Suai Loro we could only obtain information on the cultural status of crocodiles.

These new data indicate that crocodile attacks are still occurring at a high rate and that the number of reported attacks was considerably higher during 2015–2022 than during 2007–2014 in Beco (14 vs three crocodile attacks) and in Lake Ira Lalaro (19 vs 11 crocodile attacks). Crocodiles and/or risky human activities are either increasing in these areas or some historical attacks were not reported during previous assessments.

Cultural attitudes towards crocodiles were diverse amongst the four districts. In Bauro, Muapitine, Mehara, Uani Uma, Beco and Suai Loro crocodiles were regarded as sacred animals and hunting so-called grandfather crocodiles was generally taboo. In lagoon Malai Wai in Uani Uma a local fisherman was attacked and killed by a crocodile in 2020. The community was not prepared to kill or remove the crocodile unless it could be identified as a migratory so-called troublemaker crocodile from elsewhere (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Trindade, Gusmao and Pechacek2019). In Suai Loro traditional ceremonies conducted by traditional so-called crocodile owners (nain lafaek) in a dedicated crocodile house (uma lafaek) were an essential prerequisite for any activity involving local grandfather crocodiles, to prevent the crocodile becoming upset and hurting or seeking revenge against the community (Plate 1a). In Beco a local fisherman had survived a crocodile attack 3 weeks before our visit, whilst collecting mud crabs (Plate 1b). He had serious injuries and was being treated exclusively by traditional means and medicines, rejecting assistance to travel to a hospital. In a lagoon in Suai Loro several large crocodiles were present (Plate 1c), but fishermen passed within metres of them without fear of attack (Plate 1d). In Manufahí district (e.g. in Clacuc at Modomahut lagoon) this sacred status had perhaps never existed amongst residents except for amongst some ethnicities relocated to Manufahí from other districts during the period of Indonesian occupation. Here crocodiles are hunted for subsistence, when available, and eggs are harvested for food.

Plate 1 (a) Saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus owners (nain lafaek) in front of a traditional crocodile house (uma lafaek) in Suai Loro (Fig. 1), (b) victim of a crocodile attack in Beco, (c) c. 4.5 m long crocodile in a lagoon in Suai Loro, and (d) local fisher working within c. 150 m of the crocodile shown in (c). Photos (a & b): S. Brackhane; photos (c & d): Y. Fukuda.

The cultural significance of C. porosus has helped its population recover but at a high human cost in terms of attacks on people (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Gusmao and Pechacek2018a, Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Trindade, Gusmao and Pechacek2019). It is of concern that at Lake Ira Lalaro 19 attacks occurred during 2015–2022. Use of wetlands for subsistence, particularly fishing, is critical to the well-being of local people in Timor-Leste but is the activity that most attack victims were engaged in. The remoteness and access difficulties of these areas, exacerbated in the wet season, is a challenge to quantifying the distribution and size structure of the wild C. porosus population. Aerial, ground and boat surveys have a role to play in this, as does local knowledge (Brackhane et al., Reference Brackhane, Webb, Xavier, Trindade, Gusmao and Pechacek2019). Implementing effective management in local contexts requires detailed knowledge about attack contexts, agreement from local stakeholders and resources for implementation. An education campaign, similar to the Crocwise programme in Australia, could be adapted to the local context to inform local people and tourists about the risks of crocodile attacks and the local cultural status of crocodiles. Tourism (diving, snorkelling) is an important new area of economic development in Timor-Leste, but crocodile attacks could potentially undermine investment in this industry.

Human–wildlife conflict is becoming more frequent, serious and widespread in many regions as wild spaces shrink and the human population increases (Sillero-Zubiri et al., Reference Sillero-Zubiri, Caruso, Chen, Christidi, Eshete and Sanjeewani2023). In the case of saltwater crocodiles, the increasing and expanding populations in several parts of their range (e.g. Solomon Islands, Aswani & Matanzima, Reference Aswani and Matanzima2024; Malaysia) add to the potential for conflict (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Manolis, Brien, Balaguera-Reina and Isberg2021). The situation in Timor-Leste is a case study of the challenges decision-makers face in implementing a context-specific management programme without incurring high costs to local people in regions where humans and crocodiles coexist (IUCN, 2023).

Author contributions

Study design: SB, YF, GW; fieldwork: SB, YF, FMEX, VdA; data analysis: SB, YF, MG, JT; writing: SB, YF, DdAdD, RDRP, GW.

Acknowledgements

We thank CrocFest for its financial support of this study.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the British Sociological Association and Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. All work was conducted with the necessary approvals from the government authorities of Timor-Leste. Survey teams included qualified and experienced individuals from both the Timorese government and local community, ensuring effective communication with local people was achieved during informal encounters. Participation in the interviews was voluntary and informed oral consent was received from all respondents. No animals were handled during this study.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants.