There are 25 primate species in Viet Nam, more than in any other mainland South-east Asian country (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Sterling and Hurley2011; Roos et al., Reference Roos, Boonratana, Supriatna, Fellowes, Rylands and Mittermeier2013). Of these, three are endemic and Critically Endangered, namely the Cat Ba langur Trachypithecus poliocephalus, Tonkin snub-nosed monkey Rhinopithecus avunculus, and Delacour's langur Trachypithecus delacouri (Roos et al., Reference Roos, Boonratana, Supriatna, Fellowes, Rylands and Mittermeier2013; Covert et al., Reference Covert, Duc, Quyet, Ang, Harrison-Levine and Bang2017). Delacour's langur is one of several species of the Trachypithecus francoisi group, which all occur in forest on karst limestone. The species is restricted to a small area of northern Viet Nam, formerly in remnant forest patches in the provinces of Hoa Binh, Ha Nam, Ninh Binh and Thanh Hoa (Nadler et al., Reference Nadler, Momberg, Dang and Lormee2003; Workman, Reference Workman2010). The total number is estimated to be 250–300 individuals in isolated populations occupying extremely fragmented forest patches (Nadler, Reference Nadler2015; Linh et al., Reference Linh, Quyen and Nadler2019). Delacour's langur has been decimated by illegal hunting and habitat loss, with at least eight populations extirpated since 2000 (Workman, Reference Workman2010; Nadler, Reference Nadler2015). The species is categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, and has been consistently ranked among the most threatened primates (Nadler et al., Reference Nadler, Canh, Thanh and Quyet2015; Schwitzer et al., Reference Schwitzer, Mittermeier, Rylands, Chiozza, Williamson, Wallis and Cotton2015).

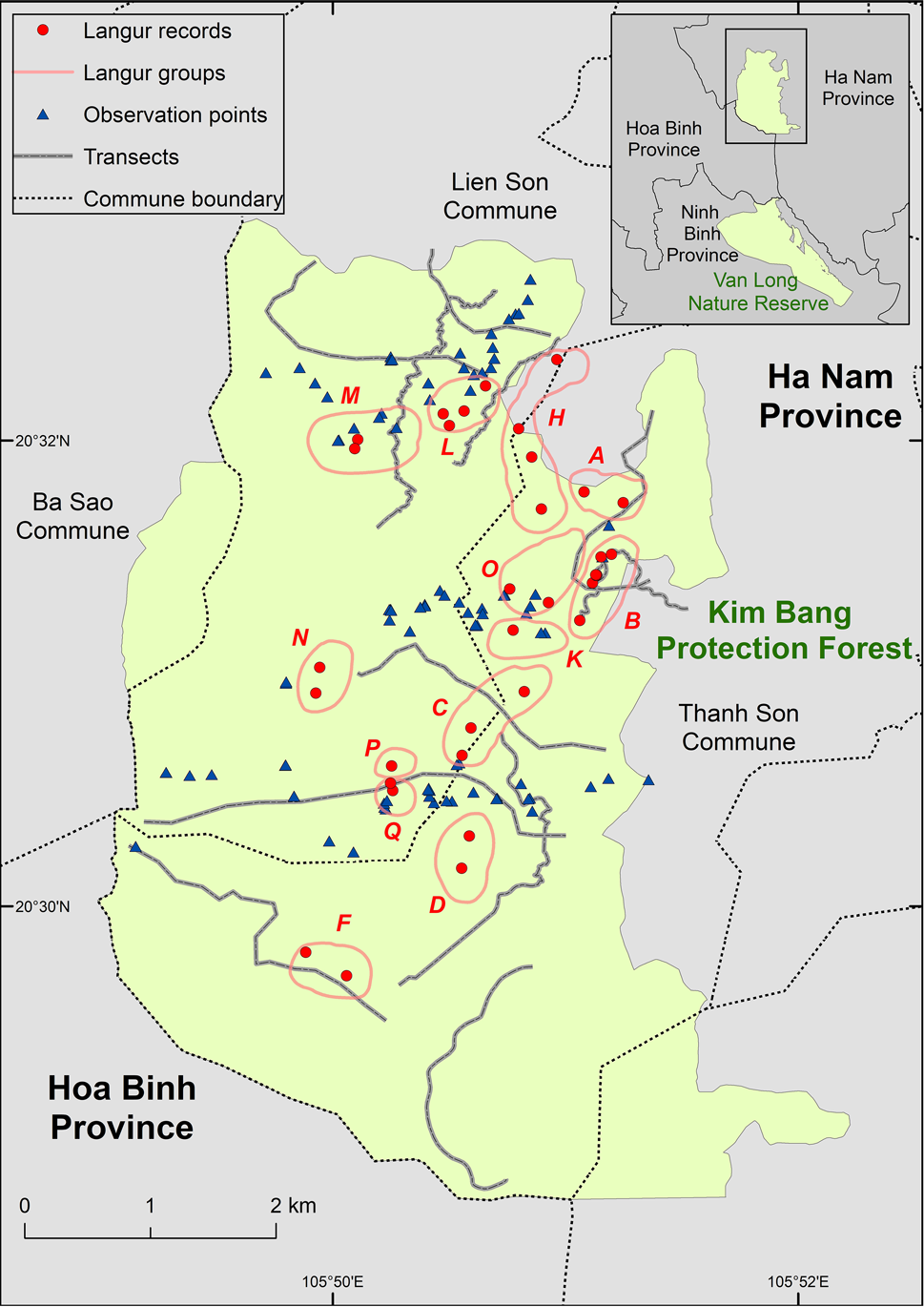

The largest known population of Delacour's langur is in Van Long Nature Reserve, Ninh Binh Province, with 176–184 individuals (Linh et al., Reference Linh, Quyen and Nadler2019). It was formerly considered the only viable population, with other populations thought too small for recovery (Nadler, Reference Nadler2015). Field surveys in the 1990s by the Frankfurt Zoological Society (Nadler & Long, Reference Nadler and Long2001; Nadler et al., Reference Nadler, Momberg, Dang and Lormee2003) in Kim Bang Protection Forest, c. 15 km north of Van Long, revealed at least 20 langurs in 1–2 groups. In the early 2010s, a study confirmed one group of 4–5 individuals, and interviews reported up to seven groups with 24–32 animals (Nadler, Reference Nadler2015). In 2016, a survey by Fauna & Flora International (FFI; Trinh-Dinh & Le, Reference Trinh-Dinh and Le2016) recorded seven groups with a total of 40 langurs. The 2016 survey, however, covered < 50% of Kim Bang Protection Forest, and no surveys were carried out in the Lien Son and Ba Sao communes, which have well-preserved forests (Fig. 1). To assess the status of the langur population throughout Kim Bang, we conducted surveys and interviewed local people during 10 August–7 October 2018.

Fig. 1 Survey locations and observations of Delacour's langur Trachypithecus delacouri, with group names (Table 1), in Kim Bang Protection Forest, and, on the inset, the location of Van Long Nature Reserve, which holds the largest population of the species.

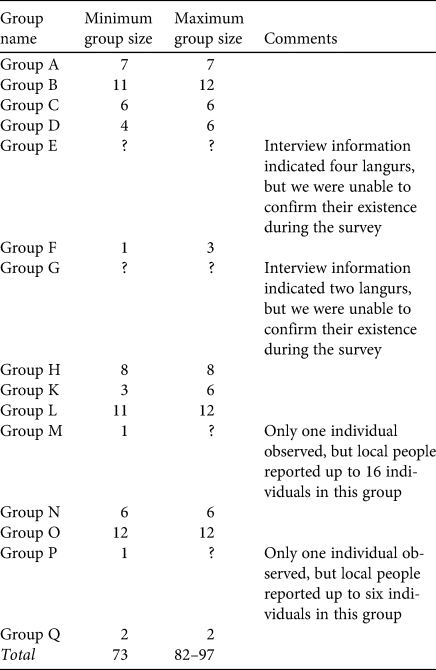

Table 1 Details of the groups and group sizes of Delacour's langur Trachypithecus delacouri in Kim Bang Protection Forest, Viet Nam. See Fig. 1 for additional information on the locations.

The Kim Bang Protection Forest is in eastern Kim Bang District, Ha Nam Province, and is managed by the commune authorities of Thanh Son, Lien Son and Ba Sao. Commune is the smallest administrative subdivision in Viet Nam; the population of each commune is 3,000–10,000 people. The site covers c. 1,500 ha in the Red River Delta region (Fig. 1), characterized by dissected limestone karst formations and narrow valleys with fragmented patches of mature secondary forest on the ridges and upper slopes, and degraded forests with mostly scrub on the lower slopes (Trinh-Dinh & Le, Reference Trinh-Dinh and Le2016). At present, the area is classified as local watershed protection forest, which means it is not a legally or nationally recognized protected area and has only a low level of protection from local law enforcement, which at least partly explains the degradation of the forest and the decline of Delacour's langur in this area (Trinh-Dinh & Le, Reference Trinh-Dinh and Le2016). However, the area has been proposed as a protected area for the conservation of Delacour's langur (Knight, Reference Knight2019).

Prior to the surveys, we spoke with seven people in local communities who were knowledgeable about the Kim Bang forests, to identify potential survey areas and to select suitable locations for transects and observation points. We collected information on locations where langurs had been seen, dates of the observations, and group size and status. Transect walks and visual and auditory observations from fixed points were used to survey the langurs (Fig. 1). We used two teams of surveyors; a team included one researcher and 1–2 local guides. Each team walked separate transects and observed from independent points, to maximize detection probability. As the adult male of a langur group frequently emits loud calls, and often sits as a sentry on prominent features such as the top of a tree or rock (Workman, Reference Workman2010), we established observation points and transects on high ground.

When langurs were spotted, we recorded time and date, geographical coordinates of the team, direction and estimated distance to the langurs, and group size and structure. The age–sex classification (adult male, adult female, juvenile, infant), followed Nadler et al. (Reference Nadler, Momberg, Dang and Lormee2003) and Workman (Reference Workman2010). We took photographs and videos of langurs and their habitat whenever possible. To avoid double counting langur groups that travelled extensively in one day, the teams compared time and location of observations, and group size and composition, at the end of each day. Any groups that could not be clearly distinguished were treated as a single group. When there were different counts for the same group, we retained both estimates (Table 1).

We recorded 13 groups and a total of at least 73 individuals (Fig. 1, Table 1), almost doubling the highest number reported in previous surveys, and including six new groups in the extended survey area. The population size could be greater, as we did not include one potential group with at least 4–6 individuals (Group P) and another with > 10 individuals (Group M) in the final tally. We were also unable to confirm the existence of two additional groups reported during the interviews (Groups E and G). Future studies should focus on these four groups.

Our conversations with local people and our observations during the survey indicated that the greatest threats to Delacour's langur in Kim Bang are poaching and habitat degradation. We detected snares and leg-hold traps in the protection forest, and a dead langur entangled in a snare. Hunting with handmade rifles, although illegal, still occurs in Kim Bang, and we saw signs of such activities (makeshift gun primers and shells) in the forest. On the eastern side of the forest, seven companies were quarrying limestone on the karst outcrop the langurs inhabit. Given the scale of the mining, we expect the available habitat for Delacour's langur will be reduced substantially.

Although the Kim Bang Protection Forest has the second largest remaining, viable population of Delacour's langur, the site has received less attention than that of Van Long, and therefore we do not know whether the population in Kim Bang has declined, although this is likely, given the existing threats. Nonetheless, the Delacour's langur population in Kim Bang could potentially recover if appropriate conservation measures are implemented in the near future. In 2020, monitoring teams supported by FFI and the Center for Nature Conservation and Development discovered evidence of recruitment, with several infants observed (H. Trinh-Dinh, pers. obs., 2020).

As Delacour's langur has disappeared from much of its former range (Nadler et al., Reference Nadler, Momberg, Dang and Lormee2003; Nadler, Reference Nadler2015), the future of the species depends primarily on the two largest populations. Given their proximity, the establishment of a biological corridor to connect them would be beneficial for the long-term conservation of this Critically Endangered species. Our findings will inform the proposed gazettement of a new protected area in Kim Bang, and will form the baseline for future monitoring of this langur population. In September 2020, an emergency proposal, including the designation of a new Species and Habitat Conservation Area in Kim Bang, signed by FFI, the Center for Nature Conservation and Development, WWF–Viet Nam, the IUCN Primate Specialist Group and other stakeholders was sent to the Prime Minister of Viet Nam for consideration.

Acknowledgements

We thank Wildlife Reserves Singapore, The Rufford Foundation, Primate Partnership Fund, Idea Wild, Global Wildlife Conservation, Primate Conservation Inc., and the Program 562 (Grant number DTDL.CN-64/19) of Viet Nam's Ministry of Science and Technology for their support.

Author contributions

Study design: all authors; fieldwork, data analysis, writing: ATN, HT-D; revision: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.