Introduction

As human populations continue to increase, people are increasingly encroaching on natural areas. As a result, the relationship between people and wildlife is often antagonistic because of competition over declining resources (Weladji & Tchamba, Reference Weladji and Tchamba2003), and thus when an increasing number of people are crowded into a limited area of land, human–wildlife conflicts are likely to increase. Such conflicts commonly arise when wildlife cause damage to crops, or kill livestock or game, and occasionally they involve attacks on people (Inskip & Zimmermann, Reference Inskip and Zimmermann2009).

Human–wildlife conflict is a growing problem worldwide (Woodroffe et al., Reference Woodroffe, Lindsey, Romañach, Stein and ole Ranah2005), and crocodilians are one of the major groups involved (Lamarque et al., Reference Lamarque, Anderson, Fergusson, Lagrange, Osei-Owusu and Bakker2009). Attacks by crocodiles and alligators are increasing in many parts of the world (Langley, Reference Langley2005), including in developed nations (e.g. by saltwater crocodiles Crocodylus porosus in Australia, Caldicott et al., Reference Caldicott, Croser, Manolis, Webb and Britton2005; and by American alligators Alligator mississippiensis in the USA, Langley, Reference Langley2005). Crocodiles are top predators and keystone species, and perform an important role in maintaining the biodiversity, structure and function of freshwater ecosystems (Thorbjarnarson, Reference Thorbjarnarson1992; Ross, Reference Ross1998; Leslie & Spotila, Reference Leslie and Spotila2001; Glen et al., Reference Glen, Dickman, Soulé and Mackey2007).

With the exception of ecotourism, interactions between people and crocodiles are rarely positive (McGregor, Reference McGregor2005), and developing ways to reduce conflict is essential to mitigate the loss of both human life and livestock (Fergusson, Reference Fergusson2002). Large carnivores are often highly valued at a global scale but have a low or negative economic value at a local scale (Dickman et al., Reference Dickman, Macdonald and Macdonald2011). To address this, local revenue from carnivore presence should outweigh the costs of coexistence (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Dickman, Gaynor, Smuts and Macdonald2015), such as through tourism or payments for presence. Management approaches to human–crocodile conflict include capture and relocation, and lethal control, of crocodiles. These actions need to be carefully monitored, as crocodiles are an economically important species (MacGregor, Reference MacGregor2002).

There are three species of crocodiles in India: the estuarine or saltwater crocodile, the marsh or freshwater crocodile Crocodylus palustris and the gharial Gavialis gangeticus. All three species were formerly found in the Sundarban but the current status of freshwater crocodiles and gharials in the region in unknown (Vyas, Reference Vyas2012). The estuarine crocodile is the largest marine reptile in India, and its population has declined as a result of indiscriminate poaching for its valuable skin (Mandal & Nandi, Reference Mandal and Nandi1989), loss of habitat, and water pollution (Das & Bandyopadhyay, Reference Das and Bandyopadhyay2012). There is little information available on conflict between people and estuarine crocodiles in the Sundarban but historical records reference its existence. During 1920–1930, when tiger Panthera tigris hunting was permitted, it was perceived that killing of people by tigers decreased and the major threat to human life was from crocodiles (Curtis, Reference Curtis1933; Vyas, Reference Vyas2012).

Estuarine crocodiles currently inhabit 2,500 km2 of the Indian Sundarban, concentrated mostly in the Saptamukhi, Thakuran, Choto Noubanki, and Mechua Khal areas (Chaudhuri, Reference Chaudhuri2007). Human–crocodile conflicts have increased since 1990, mainly as a result of large-scale human encroachment into the crocodile's territories. Our objectives were to determine the nature, extent and causes of conflict between people and estuarine crocodiles in the Sundarban, using a spatio-temporal database, and to suggest appropriate management and mitigation strategies to reduce conflict.

Study area

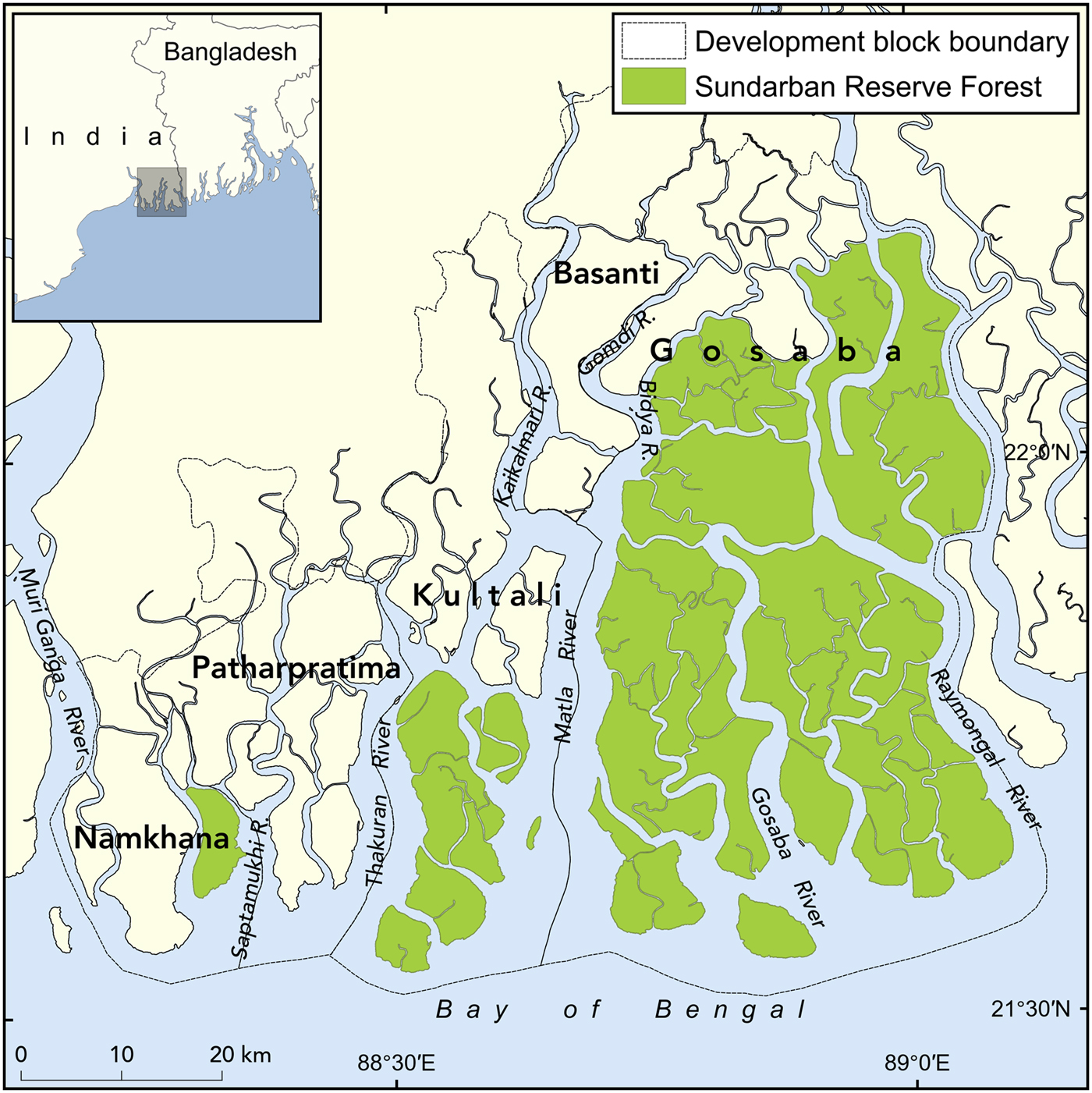

The Sundarban is one of several areas in India prone to crocodile attacks, and was chosen as the study area because of its accessibility. The undivided Sundarban (i.e. the combined mangrove region of India and Bangladesh before 1947, comprising c. 10,000 km2) is the world's largest tidal mangrove forest (Chaudhuri & Choudhury, Reference Chaudhuri and Choudhury1994), accounting for 6% of mangrove area globally (Khan, Reference Khan, Mittermeier, Mittermeier and Gil & J. Pilgrim2002). Reclamation of the Indian part of the Sundarban began as early as 1770 (Pargiter, Reference Pargiter1934), and during the next 2 centuries c. 5,364 km2 of the tidal forests were converted to farmland and habitations. The study was confined to the five community development blocks (Basanti, Gosaba, Kultali, Patharpratima and Namkhana) adjacent to the forest fringe areas, with a total area of 802 km2 covering both reclaimed land and forest areas (Fig. 1). The study area supports a rapidly growing population of 4.2 million people, with a mean density of > 900 per km2 (Census of India, 2011).

Fig. 1 Location of the five study blocks in the Indian Sundarban.

Methods

During March 2013–April 2014 we collected data using two methods. Firstly, we compiled records of crocodile attacks collected by the local government (i.e. Gram Panchayat and Block Primary Health Centres) and non-government agencies (i.e. Tagore Society for Rural Development in Gosaba, South Sundarban Janakalyan Sangha Society Information in Kakdwip, and Juktibadi Sanskritik Sanstha, Canning). Secondly, community surveys were conducted with the help of local people, using questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. These surveys were conducted door-to-door in the villages of the selected blocks. Data were collected on locality (forest range, river, village and block), date, time, activity of the victim at the time of conflict, primary and secondary occupation of the victim, result of the conflict, depredation, reflexive fear, and the role of accompanying persons following attack. The questionnaire included both open-ended and fixed-response questions, and was conducted with the head of the household or his/her representative.

Three problems were considered during the survey: (1) some non-fatal attacks are not reported to the local government, (2) incidents may be exaggerated, and (3) responses could be based on anecdotal evidence. These biases were minimized by means of a neutral introduction and non-leading question order (Milner-Gulland and Rowcliffe, Reference Milner-Gulland and Rowcliffe2007), and non-reported incidents were identified and recorded through the door-to-door survey.

Thirty villages were purposively selected on the basis of their location adjacent to forest or river. Thereafter, guided by the expert opinion of knowledgeable local people, we compiled a preliminary list of households in which either at least one family member was killed or injured during 2000–2013, or family members depended primarily or secondarily on aquatic resources. The list included 1,315 households. Both quantitative methods (χ2 test), using SPSS 16.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA), and qualitative methods (e.g. focus group discussion) were used to analyse the data.

Results

We recorded 127 incidents of human–crocodile conflict during 2000–2013, and household-level socio-economic data for each case. Most of the victims (88.19%, n = 112) were tiger prawn seed collectors (38.58%), crab collectors (26.77%) or fishers (22.83%; Table 1). People whose primary occupation was prawn seed collection were the worst affected (34.65%), followed by crab collection (20.47%) and fishing (13.38%).

Table 1 Number of victims of crocodile Crocodylus porosus attacks in the Indian Sundarban (Fig. 1) during 2000–2013, as reported in surveys of 1,315 households, according to the victims’ occupation at the time of the attack, religion and caste, and age group.

* Scheduled castes and scheduled tribes are official designations given to various groups of historically disadvantaged indigenous people in India. The terms are recognized in the Constitution of India. During the period of British rule in the Indian subcontinent they were known as the Depressed Classes.

All castes, as defined in the Census of India (2011), were affected by the conflict (Table 1). Scheduled castes were the worst affected (51.18%), followed by general caste (34.65%) and scheduled tribes (9.45%). Among prawn seed collectors scheduled castes (47.14%) were affected at marginally higher rates than the general caste population (38.57%). Hindus were affected more by conflict with crocodiles (95.28%) than Muslims (4.72%). However, the caste and occupation of victims were not significantly associated (χ2 = 9.115, df = 9, P > 0.05).

We grouped victims into four age categories: pre-adult, < 18 years; junior adult, 18–30 years; middle adult, 31–50 years; senior adult, > 50 years (Table 1). Although incidents of human–crocodile conflict were reported in all age groups, the majority of victims (77.16%) were 18–50 years of age. Only 11.02 and 11.81% of victims were > 50 and < 18 years of age, respectively (Table 1). Only one fisher < 18 years of age and two crab collectors < 18 years of age were victims. The age and primary occupation of the victims were significantly associated (χ2 = 17.075, df = 9, P < 0.1).

Considering all aquatic occupations together, 74.02% of incidents were fatal (Table 1). Fatalities were highest in non-vulnerable occupations (86.67%; including those unrelated to the aquatic environment), and lowest among fishers (58.62%). The death rate was lower (66.7%) among Muslims than among Hindus (74.38%; Table 1). Among castes, mortality was higher (91.67%) among scheduled tribes than among scheduled castes (73.85%) and the general population (70.46%).

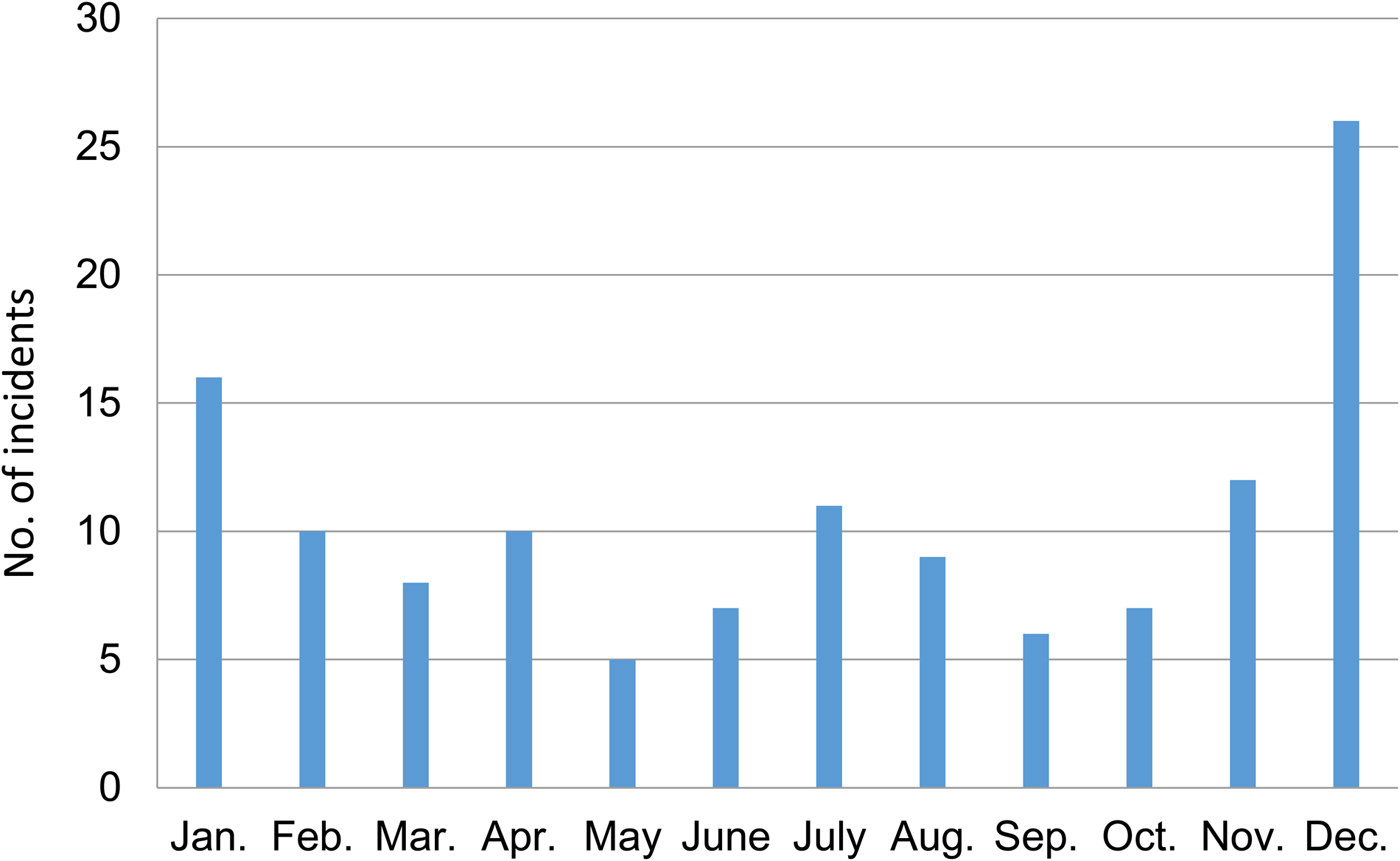

The peak month for attacks was December, during which 20.47% of attacks took place (Fig. 2). The lowest number of attacks occurred in September (4.72%). Most incidences occurred during November and the winter months of December–February (41.73%) followed by 3 months in the monsoon season (June–August; 20.47%).

Fig. 2 Monthly distribution of crocodile Crocodylus porosus attacks in the Indian Sundarban (Fig. 1) during 2000–2013, as reported in surveys of 1,315 households in five study blocks.

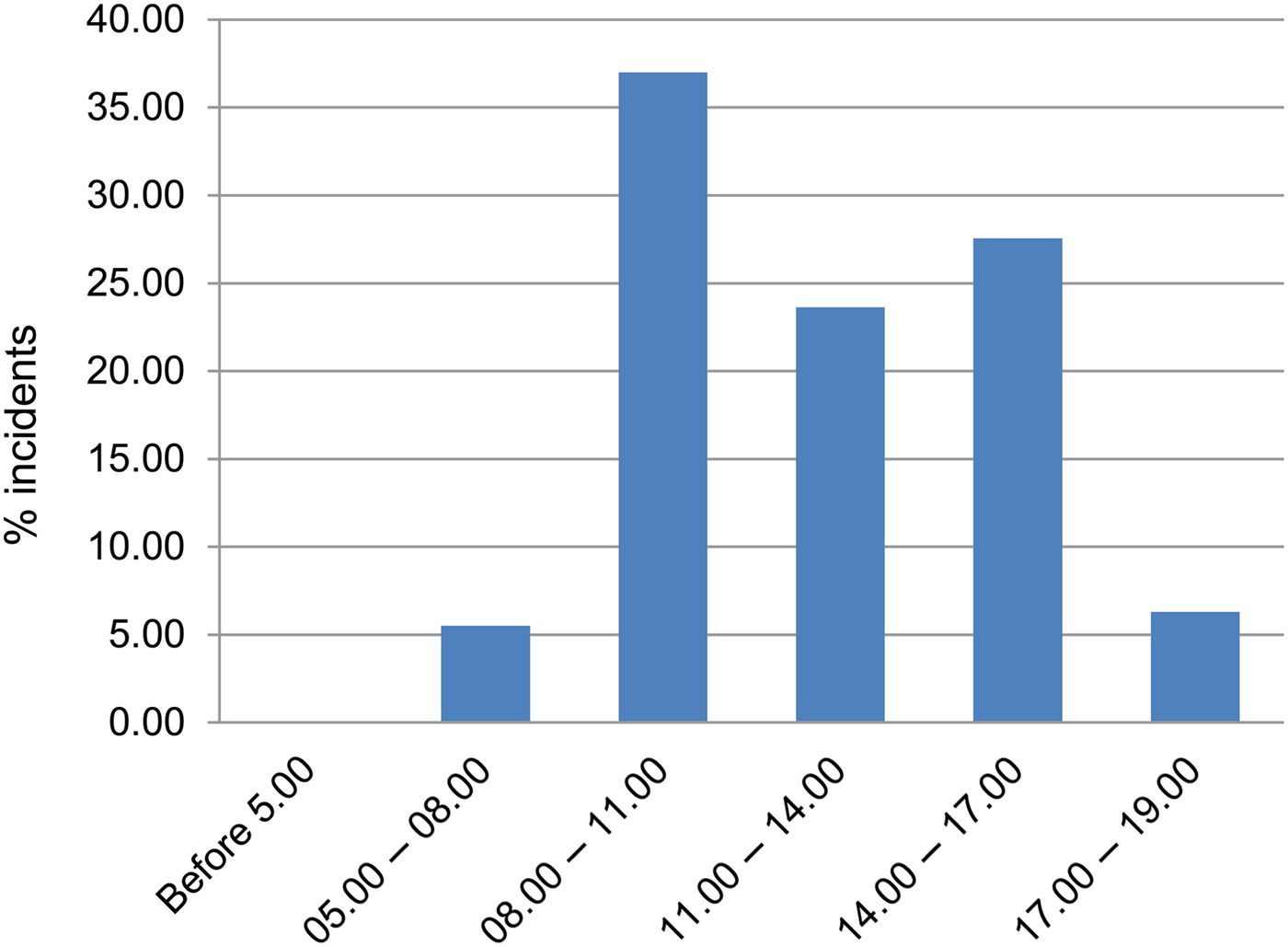

Crocodile attacks are more likely to occur during the day than at night: 37.01% of the recorded attacks took place during 08.00–11.00, 23.62% during 11.00–14.00, and 27.56% during 14.00–17.00. The majority of killings (88.19%) occurred during 08.00–17.00, when most human activity took place (Fig. 3). Of the 11.81% killed or injured at other times of the day, most were attacked in their boats while travelling to (05.00–08.00; 5.51%) or returning from (17.00–19.00; 6.30%) their occupations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Percentage cumulative frequency of crocodile attacks at various time periods study blocks (Fig. 1).

The greatest number of crocodile attacks were recorded from Gosaba block (34.65%), followed by Patharpratima (25.20%), Namkhana (18.11%) and Kultali (14.17%; Table 2). Basanti (7.87%) was the least affected block. The mortality rate from attacks was high (62.20%), with a minimum of 50% in Patharpratima and maximum of 80% in Basanti. The mean annual number of deaths was 5.64, with a minimum of 0.57 in Basanti and a maximum of 2.21 in Gosaba. Mean annual vulnerability and mortality rates per 10,000 people were 0.07 and 0.04, respectively, with the greatest vulnerability (0.13) and mortality (0.09) in Gosaba.

Table 2 Data on the characteristics of the five blocks in the Indian Sundarban where data were collected (Fig. 1) and on the number of incidents of attack by crocodiles during surveys of 1,315 households during 2000–2013.

The percentage distribution of conflicts (Table 3) across rivers indicates that the greatest number of attacks occur in the Thakuran (in Patharpratima) followed by Pirkhali (in Gosaba), Muriganga (in Namkhana), Nuchara (in Patharpratima) and Kaikalmari (in Kultali). These five rivers account for 55.2% of conflicts.

Table 3 Rivers in the five study blocks of the Indian Sundarban (Fig. 1) where frequent crocodile attacks occurred during 2000–2013.

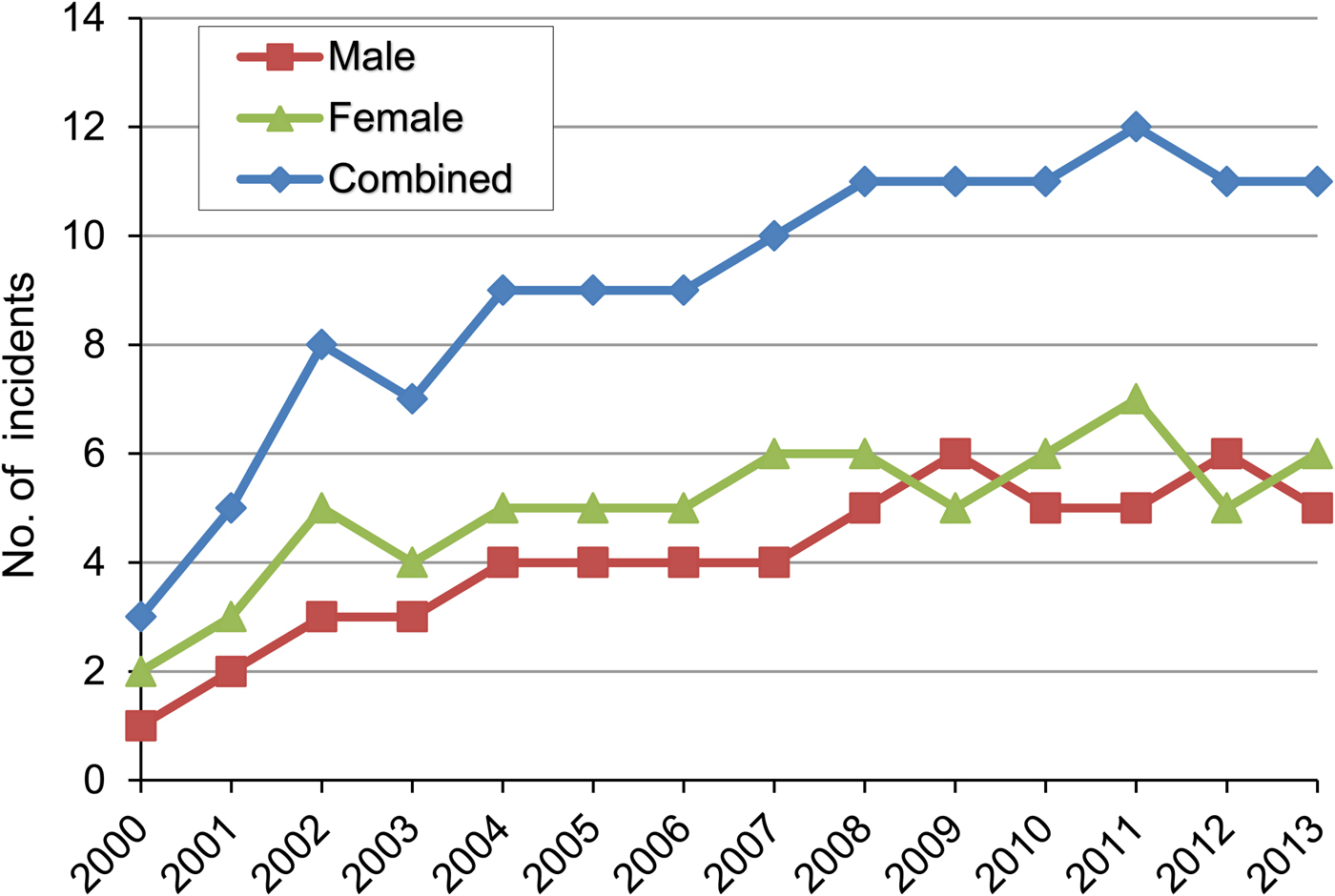

There were fewer male victims (44.88%) than females (55.12%; Fig. 4), probably because more women than men are involved in the collection of tiger prawns and crabs. Fishers are generally young males, 30–65 years of age. From 2000 to 2008 there was an increasing number of attacks on people (R 2 = 0.80), with generally 11 incidents per year from 2008 onwards.

Fig. 4 Numbers of incidents of crocodile attacks on men and women, and combined, during 2000–2013, as reported in surveys of 1,315 households in the five study blocks (Fig. 1).

Circa 63% of the respondents expressed the idea that simply sharing the same habitat was the major reason for human–crocodile conflict; 18% said that the depleted prey base caused crocodiles to search for food; 10% said that crocodiles were man-eaters, and therefore attacks were inevitable; and 9% had no opinion about why conflicts occur.

Discussion

Causes of conflict

Conflict is likely to occur in any crocodile-occupied habitat where there is human activity. Crocodilians are among the few species that cause reflexive fear in humans, perhaps because the fear of being eaten is greater than the fear of being bitten (Graham, Reference Graham1990). Many species will bite but only a few attack people as they would other prey items (Caldicott et al., Reference Caldicott, Croser, Manolis, Webb and Britton2005). Our questionnaire was designed to understand the causes of conflict, considering these factors.

Fishing activities are prevalent in the Sundarban, contributing to the livelihoods of 15% of the population (Sengupta & Rao, Reference Sengupta and Rao2003). Increasing human activity, such as large-scale collection of tiger prawn seeds, and a high frequency of crossing creeks for collection of forest products result in crocodile attacks. The mud flats on both sides of forest canals are potentially among the most likely areas of crocodile occurrence. As saltwater crocodiles consume fish (e.g. Oreochromis mossambicus, O. niloticus, Etroplus suratensis, Channa striata, Lates sp.) there is perceived competition for the same food source (Amarasinghe et al., Reference Amarasinghe, Madawala, Karunarathna, Manolis, de Silva and Sommerlad2015). Creeks or small rivers in the Sundarban are more perilous than large rivers, as crocodiles prefer muddy riverbanks during low tide for thermoregulation, and these habitats are not always available in large rivers.

As prawn seed collectors prefer to work in waist-deep water, crocodile attacks are common at low tide when mud flats on both sides of the creeks are exposed. In many cases collectors have suffered deformities from such attacks, and many have been killed (Chowdhury et al., Reference Chowdhury, Mondal, Brahma and Biswas2008). Large-scale prawn seed collection and overfishing are responsible for the low availability of fish in the Sundarban. Human–crocodile conflict is sometimes attributed to overfishing of some of the crocodile's main food sources, leading crocodiles to hunt other prey, including people (Uragoda, Reference Uragoda1994; Rao, Reference Rao, Ramamurthi and Geetabali1996; Anderson & Pariela, Reference Anderson and Pariela2005).

The incidence of crocodile attacks in the Sundarban is difficult to quantify. Undoubtedly, more people have been attacked by crocodilians than have been reported, but the level of threat is thought to be comparatively low compared to that from snakes and tigers, which are responsible for as many as 40.54 and 31.3%, respectively, of deaths caused by wildlife each year, on average (Das & Bandyopadhyay, Reference Das and Bandyopadhyay2012).

Pattern of conflict

Several authors have reported that crocodile attacks increase in warm summer months (Fergusson, Reference Fergusson2004; Caldicott et al., Reference Caldicott, Croser, Manolis, Webb and Britton2005), but in the Sundarban attacks are distributed throughout the year, with peaks occurring during the monsoon (June–August), in November and during the winter (December–February). Early monsoon is the main fishing season in the Sundarban, when thousands of prawn seed collectors enter the creeks. In winter, the crocodile mating season starts and crocodiles become aggressive to other large crocodiles. Fewer encounters with crocodiles are reported in the post-monsoon season (August–October), when the water level in rivers is high, associated with higher frequencies of tropical cyclones, which discourages people from fishing and collecting prawn seed.

Fatality rate

The fatality rate associated with human–crocodile conflict in the Sundarban is high (62.2% of attacks) compared to other parts of the world. In Australia 28.4% of attacks by saltwater crocodiles since 1971 have been fatal (Manolis & Webb, Reference Manolis and Webb2013). The fatality rate in Sri Lanka (23.7%, 1970–2008; de Silva, Reference de Silva2010) is similar to that in Australia. Fatality rates of 43.7–61% and 45.5% have been reported for Malaysian Borneo (Ambu, Reference Ambu2011; Tisen et al., Reference Tisen, Ahmad, Kwan, Robi and Osaka2011) and India's Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary, respectively (Gopi & Pandav, Reference Gopi and Pandav2009). A similar study was conducted in Mozambique during July 2006–September 2008, in which a 79% mortality rate was observed among people attacked by crocodiles (Dunham et al., Reference Dunham, Ghiurghi, Cumbi and Urbano2010). Another similar study found a relatively high fatality rate (63%) in mainland Africa (Fergusson, Reference Fergusson2004). In comparison, only 7.6% of unprovoked attacks by American alligators in the USA have been fatal (Conover & Dubow, Reference Conover and Dubow1997), which probably reflects the smaller size and less aggressive nature of this crocodilian species.

The higher rate of fatality in the Sundarban is attributable to sudden encounters with crocodiles in inaccessible places. Fishers and prawn seed collectors are most affected, as they venture illegally into deep jungle, far from villages or forest offices, where they do not have access to medical treatment if attacked.

Review of management issues

Habitat loss and degradation are the key factors affecting the natural habitat of the saltwater crocodile (Amarasinghe et al., Reference Amarasinghe, Madawala, Karunarathna, Manolis, de Silva and Sommerlad2015) in the Sundarban. Habitat restoration, including the reintroduction of mangroves on government-owned lands, and restricting the issuing of new permits for forest users are part of a Forest Department strategy for short- and long-term projects. A crocodile sanctuary was set up in 1978 at Bhagabatpur in Patharpratima block, under the auspices of the Crocodile Project, which works to increase the number of saltwater crocodiles. This crocodile-breeding facility harbours the largest number of estuarine crocodiles in India, with an egg to hatching ratio of > 70 (Singh, Reference Singh2015).

A crocodile rearing centre was also established in the same locality in 1994. By 2012, 312 crocodiles (1–1.5 m in size) of various ages reared in Bhagabatpur Crocodile Project had been released in rivers of the Sundarban. Monitoring of crocodiles in the Sundarban is difficult because the mudflats where crocodiles bask are often inundated. Also, because of the high human population density and poverty, the socio-economic dependency of people on wetland habitats cannot be controlled.

A large number of crocodiles, both juveniles and adults, are poached from the Sundarban each year (Das & Bandyopadhyay, Reference Das and Bandyopadhyay2012). Crocodile skins are valuable as they are used to make luxury items (Das & Bandyopadhyay, Reference Das and Bandyopadhyay2012). The Forest Department endeavours to prevent poaching, but with limited success as its resources are limited. Occasionally, crocodiles stray to village ponds and are rescued. This is a frequent phenomenon in September and October in Patharpratima block. This is the time when crocodiles are reported to start nesting (Amarasinghe et al., Reference Amarasinghe, Madawala, Karunarathna, Manolis, de Silva and Sommerlad2015). The Forest Department has started to translocate crocodiles from areas of conflict, and 12 individuals were translocated during the study period (Vyas, Reference Vyas2012). However, saltwater crocodiles have a strong homing instinct and may return to the original capture site (Webb & Manolis, Reference Webb and Manolis1989; Walsh & Whitehead, Reference Walsh and Whitehead1993; Read et al., Reference Read, Grigg, Irwin, Shanahan and Franklin2007).

Responses to human–wildlife conflict are varied and occur at various social–organizational scales involving actors with sometimes conflicting objectives (Mosimane et al., Reference Mosimane, McCool, Brown and Ingrebretson2014). Thus, we must consider carefully how we use the term human–wildlife conflict, and distinguish clearly between human–wildlife interactions and the underlying conflicts between conservation and other human interests (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Bhatia and Young2015).

Conclusion

In India there is little concerted effort to mitigate conflicts between people and crocodiles (Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, de Silva, Vyas, Nair, Mobaraki and Chaudhry2014), and the Forestry Department is not actively involved in addressing the problem of crocodile attacks in the Sundarban because of the low intensity of the problem compared to human–tiger conflicts. Crocodiles are opportunistic predators that are most dangerous in water and at the water–land interface (Webb & Manolis, Reference Webb and Manolis1998), and both primary (avoiding an attack altogether) and secondary preventive techniques (minimizing the harm after an attack has occurred) should be considered in addressing human–crocodile conflict (Caldicott et al., Reference Caldicott, Croser, Manolis, Webb and Britton2005). Primary prevention involves minimizing contact between people and crocodilians. Generating awareness about crocodile behaviour and the risk of prawn larvae collection by drag-netting may help people avoid attack. Banning or restricting tiger prawn and crab collection in areas of high crocodile density could also reduce the number of attacks. People whose primary occupation is non-vulnerable and who collect tiger prawns or crabs as a secondary occupation suffer a higher fatality rate and should be discouraged from collecting these resources from the creeks or rivers of the Sundarban. Existing management practices cannot eliminate the risk of crocodile attack while ensuring the conservation of the Sundarban ecosystem, and therefore a comprehensive management plan is urgently needed to reduce dependency on forest resources by introducing sustainable rural livelihood schemes (e.g. tourism, rainwater harvesting for multi cropping, poultry farming) while maintaining the ecosystem through enforcing restrictions on access to the forest. Providing training and education, microcredit and access to feasible markets is, however, a challenge for government bodies and local NGOs.

Acknowledgements

CSD is grateful to the University Grants Commission of the Government of India for providing financial support for field work in the Sundarban. We thank Professor Sunando Bandyopadhyay of the University of Calcutta and the retired wildlife biologist Carl D. Mitchell for their continuous inspiration and valuable suggestions for improving the article. We thank Dr Aznarul Islam of Aliah University, Suman Mondal, Saptarshi Sarkar, and Martin Fisher for assistance in producing the map figure.

Author contributions

This article is a joint effort by CSD and RJ.

Biographical sketches

Chandan Surabhi Das’s research focuses on socio-economic aspects of human–wildlife conflict in the protected areas of developing countries. He is also conducting extensive research on the conservation of the Sundarban mangrove forests in the context of the livelihood of forest users. Rabindranath Jana has experience in conducting statistical analysis of socio-eco-demographic data. His research interest is in social network analysis.