Dipterocarpaceae is one of the major families of ecological and economic importance in tropical and subtropical forests, with > 500 species globally (Maury-Lechon & Curtet, Reference Maury-Lechon, Curtet, Appanah and Turnbull1998; Purwaningsih, 2004). In Indonesia, there are 238 species of Dipterocarpaceae, 62% of the Malesian dipterocarp species, with Kalimantan (200 species) and Sumatra (111 species) being centres of diversity for this family (Purwaningsih, 2004). Most of these species are located in lowland forests below 1,500 m, an area with high rates of tree cutting and forest conversion (Miettinen et al., Reference Miettinen, Shi and Liew2011). Of the 179 Indonesian species of Dipterocarpaceae assessed on the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2019), 151 are categorized as threatened.

Vatica cauliflora P.S. Ashton (Dipterocarpaceae) is narrowly distributed in Kapuas Hulu District, West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia (Ashton, Reference Ashton1978). First collected in 1953 and described in 1978, the species is currently categorized globally as Critically Endangered under criteria A4cd (i.e. a reduction in population size (A) based on ≥ 80% reduction (4) and decline in area of occupancy and/or related measures (c) and exploitation (d)) on the IUCN Red List (Kusumadewi et al., Reference Kusumadewi, Hamidi and Randi2019). Nationally, the species is not included in the list of protected flora (Ministerial Decree of Environment and Forestry, 2019). As the species is only known from one collection, of type specimens, and because habitat degradation in Kapuas Hulu resulting from tree cutting and forest conversion is ongoing, conservation action for V. cauliflora may be urgently needed. We therefore carried out surveys for V. cauliflora to assess its population status and to reassess the species' conservation status using the IUCN Red List criteria and categories.

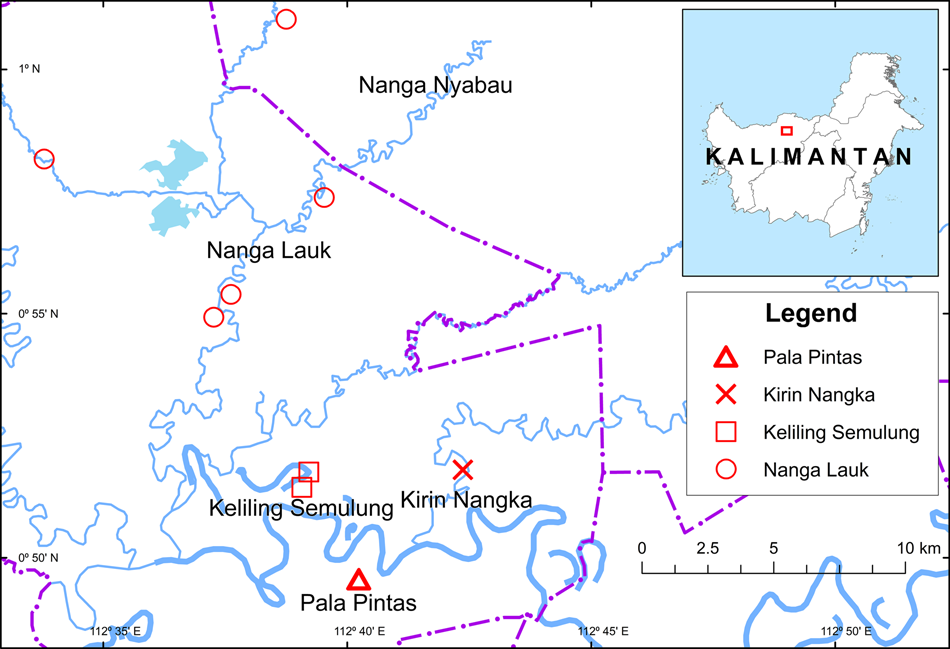

Based on information from herbarium specimen sheets, in December 2019 and February 2020 we surveyed for V. cauliflora in four villages of Kapuas Hulu District, West Kalimantan Province: Nanga Lauk, Keliling Semulung, Kirin Nangka and Pala Pintas (Fig. 1). In each location where we found the species, we recorded the following data: habitat type, altitude, geographical location, number of individuals and any apparent threats. We also measured the diameter at breast height (DBH, measured at 1.3 m above the ground) of all individuals. The population was then categorized into 10 DBH classes from 0–5 to > 45 cm. In addition, the extent of occurrence (EOO) and area of occupancy (AOO) of V. cauliflora were calculated using GeoCAT (Bachman et al., Reference Bachman, Moat, Hill, Torre and Scott2011). Using data on population size and structure, geographical range and threats, we assessed the extinction risk for V. cauliflora using the IUCN Red List criteria (Standards and Petitions Committee, 2019).

Fig. 1 Locations of our population surveys of Vatica cauliflora in four villages in Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan: Nanga Lauk, Keliling Semulung, Pala Pintas and Kirin Nangka Village.

A total of 179 individuals were located during the surveys in Nanga Lauk, Keliling Semulung and Kirin Nangka villages, of which 36 (20.1%) were estimated to be mature. We did not locate the species in Pala Pintas village. Vatica cauliflora was found at 18–40 m altitude along riverbanks on non-inundated soil. Based on the result of the GeoCAT calculation, the species has an EOO and AOO of 139.998 and 32 km2, respectively. The population is dominated by young individuals of the diameter class of 0–5 cm. The lower number of individuals in the higher diameter classes (Fig. 2) is indicative of low survivorship or harvesting, or both. During the survey we observed that a few mature individuals of the species had been harvested, and local people indicated to us that the timber is good for boat and house construction. The limited number of trees in the intermediate or larger size classes may indicate that adult trees have been unable to produce vigorous offspring. Study of the genetics of this species would provide insight into any inbreeding issues (Chua et al., Reference Chua, Nurulhuda, Hamidah and Saw2004; Robiansyah & Davy, Reference Robiansyah and Davy2015). We believe this species is ecologically closely associated with Vatica havilandii Brandis, another threatened Dipterocarpaceae categorized as Critically Endangered (Ashton, Reference Ashton1998): in each location where we found V. cauliflora we also found V. havlandii. The raised areas along riverbanks where we found V. cauliflora are referred to locally as kirin. These areas are cleared for use as rubber tree Havea brasiliensis or kratom Mitragyna speciosa (used as a traditional medicine) plantations or rice paddies (Plate 1). The populations of V. cauliflora that we found are in the remaining forest patches between agricultural fields.

Fig. 2 The number of V. cauliflora individuals (of a total of 179) in 10 DBH classes in Nanga Lauk village, Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan (Fig. 1).

Plate 1 Identified threats to Vatica cauliflora included (a) tree felling (this photograph is of an unknown species being cut), and habitat conversion into (b) rubber tree Havea brasiliensis plantation, (c) kratom Mitragyna speciosa plantation, and (d) rice paddy.

Based on our findings, we recommend that V. cauliflora is categorized as Critically Endangered based on criteria A4cd;C2a(i);D, with a population size reduction (A) based on a decline in AOO, EOO and habitat quality (c) and potential levels of exploitation (d); small population size and decline (C) as the number of mature individuals is < 250 and there is an inferred continuing decline in the numbers of mature individuals (2) and no subpopulation is estimated to contain more than 50 mature individuals (a(i)), and the number of mature individuals is < 50 and therefore the population is small or restricted (D).

During the survey we collected seedlings of V. cauliflora for the ex situ collection at Bogor Botanic Gardens. After 6 months, 11 of the 29 seedlings collected survived in the nurseries. The low survival rate may be a result of absence of fungal mycorrhiza from the roots of the seedlings, a key component for growth in other dipterocarps (e.g. Smith, Reference Smith1994). The collections will be used for education within the public display, research and as a potential source of material for reinforcement plantings of the species. The collection of seeds from different trees will be required to ensure the full representation of the species’ genetic diversity in ex situ collections. This is of particular importance in the conservation of endemic species with restricted ranges (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Chen, Li, Dao and Sun2016). Nanga Lauk village has secured management rights for a 1,430 ha forest within its jurisdiction. We met with the management staff (Lembaga Pengelola Hutan Desa), during which we recommended the inclusion of areas identified as V. cauliflora habitat into routine patrol coverage, to contribute to the in situ protection of this Critically Endangered species.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Kesatuan Pengelolaan Hutan Kapuas Hulu and Kesatuan Pengelolaan Hutan Desa Nanga Lauk for their assistance and for permission to collect seedlings. This study was fully supported by the National Geographic Fund (Grant No. NGS-44976C-18).

Author contributions

Study design, fieldwork: IR, EP, DSR; data analysis, writing: IR, EP, DSR, JL.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Survey and collection of specimens were with the permission and under the supervision of the local government, and this research otherwise abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.