The urban population in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to double to c. 1.1 billion by 2050 as a result of rural to urban immigration, and > 80% of that increase will occur in West African cities (World Bank, 2016). This urbanization may have positive effects in driving the economic development of the continent but may also cause unprecedented environmental damage (Oates et al., Reference Oates, Bergl and Linder2004).

The population increase in cities places greater demands on natural resources, especially food. Bushmeat, or the meat of wild animals, is a crucial source of protein for rural people and is also consumed by urban inhabitants, often as a commodity (Fa et al., Reference Fa, Peres and Meeuwig2002a,Reference Fa, Juste, Burn and Broadb, Reference Fa, Seymour, Dupain, Amin, Albrechtsen and Macdonald2006; Brashares et al., Reference Brashares, Golden, Weinbaum, Barrett and Okello2011). Although bushmeat may be less important for the food security of large cities (Hema et al., Reference Hema, Ouattara, Parfait, Di Vittorio, Sirima and Dendi2017; Luiselli et al., Reference Luiselli, Hema, Segniagbeto, Ouattara, Eniang and Di Vittorio2017a,Reference Luiselli, Petrozzi, Akani, Di Vittorio, Amadi and Ebereb), the overall volume consumed can be large and this can have consequences for the targeted wildlife populations (van Vliet et al., Reference van Vliet, Nasi, Taber, Shackleton, Shackleton and Shanley2011). To guide behaviour-change campaigns there is a need to ascertain which consumer groups should be targeted, and whether this varies by geographical location. Here we analyse the responses of > 2,000 interviewees from six large urban centres (all with > 500,000 inhabitants) in four West African countries, and highlight similarities and differences between them.

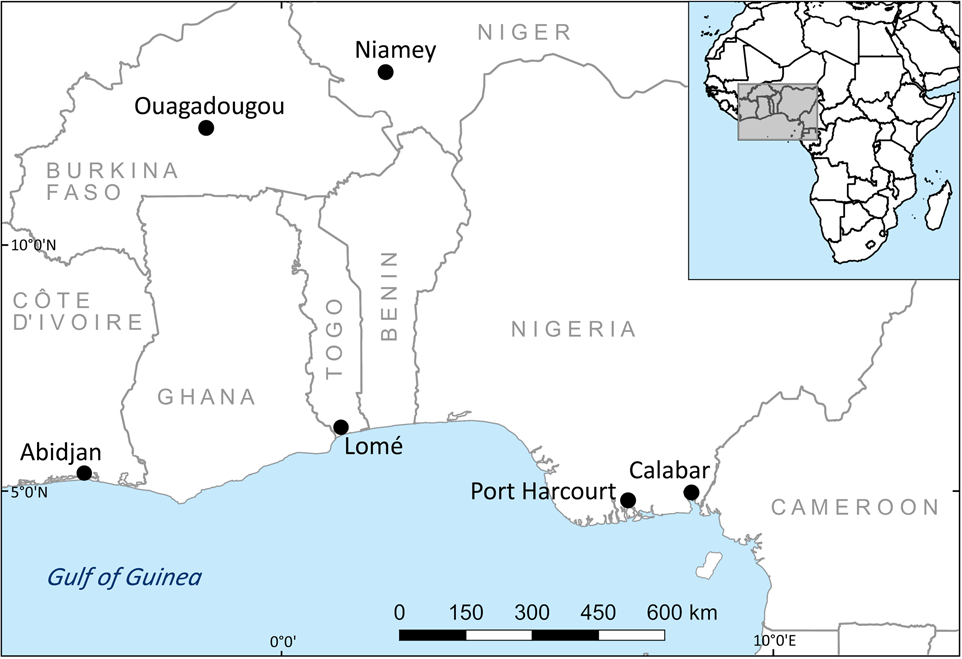

During 2012–2017 we conducted face-to-face interviews, using a standardized questionnaire, with 2,040 people in Nigeria (Port Harcourt, n = 422 and Calabar, n = 452), Togo (Lomé, n = 264), Burkina Faso (Ouagadougou, n = 262), Côte d'Ivoire (Abidjan, n = 368) and Niger (Niamey, n = 272) (Fig. 1). African scientists and students amongst the authors conducted all interviews in the appropriate local language. Interviewees were selected randomly at marketplaces, canteens, restaurants, roadsides, hairdressing salons, food shops and other gathering places. This involved stopping the first adult (we did not interview minors) met after a given time period (in minutes), with the time interval generated by a random number generator. Interviewees were informed of the aims of the project and then asked for their verbal consent before proceeding. The identity of interviewees was kept anonymous to ensure privacy (St. John, 2010; Nuno & John, Reference Nuno and John2015).

Fig. 1 Locations of the six cities in West Africa where interviews were conducted to investigate bushmeat consumption.

In each interview we recorded the gender (male or female) and age (18–25, 26–50, ≥ 51 years) of the interviewee. To avoid interdependence of the data, we did not question multiple members of the same family, or people living in the same house, even if they were not related (Hema et al., Reference Hema, Ouattara, Parfait, Di Vittorio, Sirima and Dendi2017).

We asked the following questions: Do you like eating bushmeat? If yes, how often do you eat bushmeat? If not, do you eat it on occasion nevertheless? We also asked about reasons for consuming (e.g. because bushmeat is a cheaper alternative) or not consuming bushmeat. Interviewees were then asked if they ate bushmeat regularly (normally at least once per week, but at least 2–3 times per month), occasionally (c. once per month or less often) or never. Interviewees who answered that they consumed bushmeat only occasionally were then asked whether they chose the type of animal, or whether their choice was based on which species were available, or on the price compared to domestic meat.

Although we informed all interviewees that our study was not linked to any government department, we acknowledge that some level of misrepresentation may have occurred because of fear of repercussions, as the bushmeat trade is illegal in some areas (e.g. Burkina Faso; Hema et al., Reference Hema, Ouattara, Parfait, Di Vittorio, Sirima and Dendi2017).

To compare frequency differences among respondents who often, rarely or never ate bushmeat we used a χ 2 test. We used PASW 11.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA) for all statistical analyses, with α = 0.05.

Across all six cities a mean of 62.2 ± SD 26.2% of men and 72.1 ± SD 22.1% of women answered they would never eat bushmeat (χ 2 = 0.10, df = 5, P = 0.999), and 12.8 ± SD 8% of men and 8.8 ± SD 1.7% of women said they liked bushmeat and ate it regularly (χ 2 = 0.17, df = 5, P = 0.998). There were no significant differences in the proportions of interviewees who said they ate bushmeat only rarely (χ 2 = 7.79, df = 5, P = 0.169).

Between cities there was a significant difference in the frequency of men indicating they never eat bushmeat (χ 2 = 29.13, df = 5, P < 0.001), with fewer men in Ouagadougou and Lomé stating they never eat bushmeat (Fig. 2). The frequency of women indicating they never eat bushmeat also varied significantly between cities (χ 2 = 27.4, df = 5, P < 0.001), with a similar pattern in Ouagadougou and Lomé as for men.

Fig. 2 Per cent of men and women interviewed in each of the six study cities (Fig. 1) who said they ate bushmeat often, rarely, or never.

The frequency of both men and women declaring they rarely eat bushmeat varied significantly between cities (χ 2 = 24.2, df = 5, P < 0.0001 and χ 2 = 23.7, P < 0.001, respectively), with Ouagadougou differing in that more people than expected answered this question positively (Fig. 2).

The proportion of men declaring they eat bushmeat frequently varied significantly between cities (χ 2 = 25.4, df = 5, P < 0.0001), with a higher proportion in Lomé (Fig. 2). The proportion of women declaring they eat bushmeat frequently did not differ significantly between cities (χ 2 = 10.1, df = 5, P = 0.068). The least consumption of bushmeat was amongst younger interviewees, independent of city and gender (χ 2 test, P > 0.500; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Age-distribution of (a) male and (b) female respondents who said they never eat bushmeat for each of the six study cities (Fig. 1). More younger than older people, irrespective of their city of origin, stated that they never eat bushmeat.

Of the 620 people who responded to the question ‘why do you eat wild meat regularly?’, 433 said it was because they liked the taste, 141 because of its availability, and 162 consumed it only during traditional events. Of those declaring that they don't eat bushmeat (n = 1,420), 933 said they did not like the taste, 196 said it was difficult to find and 764 had health concerns. Several people gave multiple reasons, and therefore the subtotals sum to more than the total.

As far as we are aware, our study is the first to examine bushmeat consumption patterns in large cities in West Africa. Given the large sample size, we are confident that the patterns emerging are representative and, given the simplicity of our questions, we consider that significant bias is unlikely. As all interviews were administered by nationals and in their own language, false interpretations of the questions are also unlikely. However, certain demographic groups were under-represented in our study in some cities (e.g. Ouagadougou, where only seven men aged 18–25 years were interviewed), and this may have partially affected our findings.

Three clear results arise from our surveys: (1) c. 30% of people ate bushmeat, but many of them only occasionally, (2) there were no difference between sexes, and (3) younger cohorts of both sexes tended to avoid consuming bushmeat. We also found differences in bushmeat consumption between cities and rural areas (Luiselli et al., Reference Luiselli, Hema, Segniagbeto, Ouattara, Eniang and Di Vittorio2017a,Reference Luiselli, Petrozzi, Akani, Di Vittorio, Amadi and Ebereb).

The fact that younger men and women were less likely to eat bushmeat compared to the older groups is an important finding that may indicate a shift in eating patterns away from more traditional foods. This trend may indicate a nutritional transition in sub-Saharan populations that are modernizing as a result of increased socio-economic development associated with urbanization and acculturation (Vorster et al., Reference Vorster, Kruger and Margetts2011). Informal observations of young interviewees who stated they never ate bushmeat revealed that their dress was non-traditional (they wore western-style clothes), they frequented clubs and discotheques, used social media and smartphones, often possessed a personal computer, watched pay-per-view television channels, and routinely consumed fast food (hamburgers, shawarma, pizza). Thus they may consider some cultural attributes (such as bushmeat consumption) to be unfashionable.

Bushmeat supply to urban markets and the impact of the Ebola crisis (Akani et al., Reference Akani, Dendi and Luiselli2015a; Ordaz-Németh et al., Reference Ordaz-Németh, Arandjelovic, Boesch, Gatiso, Grimes and Kuehl2017) may have been important factors determining bushmeat consumption. In Ouagadougou, for example, the lack of bushmeat consumption could be related to the illegality of the bushmeat trade, and also to the fact that the source areas (mostly protected areas and adjacent buffer zones) are at a considerable distance from the city (Hema et al., Reference Hema, Ouattara, Parfait, Di Vittorio, Sirima and Dendi2017). In Nigeria, where bushmeat markets are open, and usually close to the main urban centres (e.g. the Oigbo and Omagwa markets for the Port Harcourt metropolitan area), social factors may be more important (Akani et al., Reference Akani, Amadi, Eniang, Luiselli and Petrozzi2015b).

We predict that, with the ongoing expansion of cities in West Africa, progressively fewer people will consume bushmeat on a regular basis. The potential implications of this development on species conservation merits long-term study.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, Conservation International, the Turtle Conservation Fund, Andrew Sabin & Family Foundation, T.S.K.J. Nigeria Ltd, IUCN/Species Survival Commission Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Aquater S.p.A. and Snamprogetti S.p.A.

Author contributions

Study design: LL, BBF, JEF; fieldwork: all authors; data analysis and writing: LL, JEF.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research complied with the ethical guidelines developed by the British Sociological Association and the Code of Conduct for Oryx authors.