Introduction

There is growing concern about the potential impact of the bushmeat trade on a range of animal species (Robinson & Bennett, Reference Robinson and Bennett2000). Attention has often focused on primates and other large mammals (Bowen-Jones & Pendry, Reference Bowen-Jones and Pendry1999) and to date there has been little information on bats. There is some evidence that hunting and trade is having a significant impact on bat populations in the Pacific islands and South-East Asia (Mickleburgh et al., Reference Mickleburgh, Hutson and Racey2002) and also in Madagascar (Jenkins & Racey, Reference Jenkins and Racey2008) but there is no overall view of its potential global impact on bats. Furthermore, recent reviews of emergent viral diseases in bats have raised concerns that eating bats as bushmeat may transmit such diseases (Messenger et al., Reference Messenger, Rupprecht, Smith, Kunz and Fenton2003).

The low reproductive rate of bats makes them especially vulnerable to harvesting for bushmeat. In several life-history characteristics bats are similar to primates that are severely impacted by the bushmeat trade (Bowen-Jones & Pendry, Reference Bowen-Jones and Pendry1999). Bats are long-lived and often roost communally, which increases their visibility and susceptibility to hunters. Their vulnerability may be further increased by roost location and fidelity. Roosts, such as caves and trees, are vulnerable to disturbance and bats return seasonally to roost sites, making them predictable targets. Many bat species also face other threats, such as habitat loss, throughout their range, and these threats may interact with hunting to increase their vulnerability further. The global status of bats is reviewed by Mickleburgh et al. (Reference Mickleburgh, Hutson and Racey1992; for Old World fruit bats) and Hutson et al. (Reference Hutson, Mickleburgh and Racey2001; for all other bats).

Over 20% of all mammal species are bats (Simmons, Reference Simmons, Wilson and Reeder2005). On some islands bats may be the only native mammals and may be keystone species in ecosystems (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Elmqvist, Pierson, Rainey, Wilson and Graham1992) as pollinators and seed dispersers of plants, many of which are economically important (Fujita & Tuttle, Reference Fujita and Tuttle1991). The hunting of bats for bushmeat could therefore be a significant threat to their populations, and it is of crucial conservation and economic importance to discover the extent of hunting. We present here the results of a global survey of the use of bats as bushmeat, discuss the potential conservation problems this causes, and make recommendations on how these problems could be tackled.

Methods

This study was initiated over April–September 2004 using two principal methods. The first approach was a literature review. This included literature accumulated by a Fauna & Flora International review of the bushmeat trade (Bowen-Jones et al., Reference Bowen-Jones, Brown and Robinson2002) together with online publications and media reports. Most material reviewed was in English; some was in Spanish and French. The second approach involved a questionnaire (Appendix 1) widely distributed by e-mail and advertised in the journal Phelsuma and in African Bat Conservation News. The questionnaire requested information about traditional and current use of bats as bushmeat, the impact on bat populations, the techniques used to hunt bats and the relative importance of bats in local bushmeat trade. Where relevant, the basis of the information provided was also queried: for example, the suggestion that hunting adversely affected bat populations was only occasionally supported by research. Where necessary, data from questionnaires were clarified and supplemented by further enquiries. Anecdotes and other information from respondents were also noted.

Results

Literature review

The literature review revealed 119 references with some information indicating bat consumption, including 87 journal papers, seven media reports, three web articles, four university theses or other manuscripts, nine government reports and 20 NGO reports. Given the volume of literature on bushmeat, bat consumption is not a prominent topic. Thirty-one apparently comprehensive studies of bushmeat hunting or trade did not mention bats. Whilst additional reports may exist, especially in languages other than English, the references reviewed are likely to give a representative indication of the level of use of bats as bushmeat. Information provided by respondents about the use of bats in traditional medicine will appear elsewhere. The terms fruit bat and flying fox are used interchangeably for members of the Pteropodidae.

Questionnaire

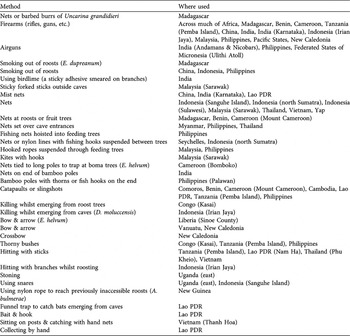

A total of 109 individuals responded to the request for information, with 90 completing questionnaires (Appendix 2). The respondents provided 138 reports on bat consumption (Table 1) and the geographical distribution of these is given in Table 2. The methods used to hunt bats are listed in Table 3. The information below only covers areas where significant bat consumption has been reported (Table 2). Other areas, such as Eurasia, North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Australia, New Zealand, North and Central America and the Caribbean are excluded because there was little or no evidence of consumption of bats.

Table 1 Summary of the use of bats as bushmeat by region and country, with information on levels of consumption, extent of trade, taxa targeted, hunting methods used, any legal controls on hunting, references, and overall summary.

1 1, No evidence of consumption; 2, Rarely eaten, no major threat; 3, Regularly eaten, no apparent threat; 4, Regularly eaten, probably serious threat

2 1, No internal or external trade; 2, Internal but no external trade; 3, Internal & external trade

3 Where known, individual species are identified. In some cases, the information given is more general, referring to genera or particular groups of bats (e.g. cave-dwelling species).

4 1, Firearms/airguns; 2, Nets; 3, Direct killing; 4, Other; X, No information (see also Table 3)

5 1, Well controlled; 2, Limited control; 3, No known control of hunting; X, No information

6 Refers to published information. Where no reference is shown the information has come from the returned questionnaires and anecdotal information.

Table 2 Geographical distribution of reports on bat consumption and any perceived problems. This is based on 138 records, including questionnaires (Appendix 1) returned and anecdotal information provided. Only regions where there was evidence of significant consumption of bats have been included in our analysis.

* Includes all of Europe, Russia and former Soviet Republics

Table 3 A summary of different methods used to hunt bats and the geographical areas where these are known to be deployed.

The use of bats as bushmeat

Generalizations concerning each area surveyed are presented in Table 1. Specific details are given below, by region.

South-East Asia

Cambodia Hunting has impacted bat populations, particularly Tadarida plicata.

Indonesia Bergmans & Rozendaal (Reference Bergmans and Rozendaal1988) noted > 100 Pteropus alecto for sale by one trader in a market in Sulawesi in 1982 and several other species were also regularly traded. Clayton & Milner-Gulland (Reference Clayton, Milner-Gulland, Robinson and Bennett2000) made detailed observations of the meats, including bat meat, in markets in north Sulawesi; in the early 1990s a single fruit bat was worth USD 0.23–1.14, and 25–50 bats per week were typically sold; this reached 300 in 1997. In each of two markets in Ujung Pandang, Sulawesi, 100–200 flying foxes were traded daily and c. 8% of bats from Ujang Pandang were exported to supermarkets in Manado City (Heinrichs, Reference Heinrichs2004). In Jakarta Pteropus vampyrus were offered by at least two market vendors for USD 10 each, who each sold c. five per week (Fujita & Tuttle, Reference Fujita and Tuttle1991). Bats were also readily available at Manadonese restaurants (Fujita, Reference Fujita1988). However, on Karakelang, most bats were eaten by the trappers and hunting was not commercially driven (Riley, Reference Riley1998). Whole roosts could be devastated by harvesting for markets in north Sulawesi (Clayton & Milner-Gulland, Reference Clayton, Milner-Gulland, Robinson and Bennett2000) and five species, including one endemic, were threatened by hunting on the islands of Sangihe and Talaud, with Acerodon celebensis possibly warranting threatened status (Riley, Reference Riley2002). Fruit bats were heavily hunted on Karakelang Island (Riley, Reference Riley1998). Market surveys and colony observations indicated that c. 30,000 bats were killed per year in southern Sulawesi, and overharvesting seriously threatens flying fox populations (Heinrichs, Reference Heinrichs2004). Populations of A. celebensis and Pteropus griseus mimus may have been decimated and P. alecto populations reduced by 25% (Heinrichs, Reference Heinrichs2004). In some regions smaller bat species were hunted because flying foxes were no longer present (Heinrichs, Reference Heinrichs2004). The impact of hunting in Indonesia may be exacerbated because hunters leave obstructions in place that are used to catch cave bats, which then preclude re-establishment of some colonies. In Kalimantan c. 4,500 Pteropus vampyrus natunae were taken from one location over a month, resulting in severe population decline (Streubig et al., 2007). The bats were sold in markets for USD 0.63–2.20 each. There has been some response to problems in this region. Bat Conservation International and Fauna & Flora International supported the work of Scott Heinrichs to educate people in Sulawesi about the role that bats, particularly flying foxes, play in the ecosystem, and their conservation status, and he liaised with local academics, students, restaurateurs and villagers.

Lao PDR The only confirmed large colony of the wrinkle-lipped bat Tadarida plicata is heavily exploited, with several thousand bats per day being sold in the market of Louang-Namtha. Tadarida teniotis were also sold in markets at Ban Lak (Francis et al., Reference Francis, Guillen, Robinson, Duckworth, Salter and Khounboline1999) and bats may have been exported to Thai markets (Robinson, Reference Robinson1994). In the Nam Ha protected area trade was primarily local, with 97% of reported sales being to people from the same province and 35% to people from the same village (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Singh, Dongdala and Vongsa2003). However, some bat species were not locally perceived as threatened; less than 1% of households surveyed in Nam Ha thought Cynopterus sphinx was decreasing in abundance (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Singh, Dongdala and Vongsa2003).

Malaysia Bats are regarded as a luxury meat in cities. Most vendors surveyed by Fujita & Tuttle (Reference Fujita and Tuttle1991) reported selling 200–300 bats per season at USD 2.50–3.30 each. There have been severe declines in the abundance and distribution of P. vampyrus throughout Peninsular Malaysia, with most extant colonies located deep in isolated and inaccessible forests and in dense riparian vegetation. Populations of P. vampyrus in eastern Malaysia are also declining (Mohd-Azlan et al., Reference Mohd-Azlan, Zubaid and Kunz2001).

Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia) The Department of Wildlife and National Parks sells permits, each allowing 50 P. vampyrus to be shot, and about 40 such permits were issued in 1 year in Perak. Mohd-Azlan et al. (Reference Mohd-Azlan, Zubaid and Kunz2001) calculated that permits to shoot 56,000 P. vampyrus were issued between 1990 and 1996.

Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak) In Sarawak hunting occurred mostly during the bats’ reproductive season (Fujita, Reference Fujita1988). Cheiromeles torquatus was opportunistically captured at roosts by indigenous people. The Iban of Sarawak could net up to 200 bats per night. Bats may also be shot for sport or to eradicate them from fruit plantations (Fujita & Tuttle, Reference Fujita and Tuttle1991). Although few traders specialized in bat meat, one vendor in Sarawak sold 150–200 bats per week at c. USD 3 each, hunted by the Iban and sold to Chinese customers. Non-specialist vendors were estimated to sell a few thousand per year. Bat trade may thus be economically important to at least some Iban.

Myanmar Local boys at Nadkon village cave, and cement factory workers at Saddan-Sin cave, both in Kayon state, collect whatever species they can for consumption. In at least one location (Nagamauk Cave) hunting stops during the breeding season. Bats are only traded locally to supplement income. For example, in Kyauk-Ta-Lone village, 1 kg of bats may be sold for c. USD 1 (Bates, Reference Bates2003). Bat populations are probably not threatened by hunting, although impacts may vary according to attitudes in each village. Many cave roosts in Myanmar, especially larger ones, are protected from overharvesting by local communities, to ensure the supply of guano (Bates, Reference Bates2003).

New Guinea (Papua New Guinea and Irian Jaya) The Hatam, a local tribe of the northern Arfak Mountains of Irian Jaya, eat both fruit and insectivorous bats. Bats are also an additional source of protein for those practising slash-and-burn agriculture. Fruit bats were probably unsustainably harvested by at least one group (Cuthbert, Reference Cuthbert2003a). In one village of c. 1,000 people 100–150 bats were taken per year. When one large roost site was protected by these villagers its bat population increased. Elsewhere, harvesting levels by other groups, such as the Hagahai, may be sustainable (Hladick et al., Reference Hladick, Hladick, Linares, Pagezy, Semple and Hadley1993). The decline and possible extinction of Aproteles bulmerae at Luplupwintem cave in the 1970s was probably because of the effects of hunting with guns (Flannery, Reference Flannery1995a). In the early 1990s hunting was thought to have caused the numbers of Dobsonia moluccensis in a large cave near Herowana to fall from many thousands to c. 200 (Cuthbert, Reference Cuthbert2003b). Villagers voluntarily agreed to stop hunting bats in the large cave and to harvest from small caves or take foraging individuals. Counts of emergent individuals at the cave in 1992, 1995, 1996 and 2003 showed a clear rise in bat numbers, demonstrating the possibility of sustainable bat hunting (Cuthbert, Reference Cuthbert2003b).

Philippines P. vampyrus and Acerodon jubatus are preferred because of their larger size. Different species are important in different areas: for example, Dobsonia chapmani may be preferred in Negros but insectivorous bats are preferred in Montalban, Luzon. In south-western Negros bat meat is second in importance to herpetofauna but in the Tagbanua community in south Palawan it represents only 5% of game caught (Lacerna & Widmann, Reference Lacerna, Widmann, Goeltenboth, Milan and Asio1999). There is some local bat meat trade that may involve people living far away from roosts. Although 150,000 bats were counted at roosts in the late 1920s, no group larger than a few hundred was observed by Heaney & Heideman in 1987. After it was thought to have been hunted out of caves in Negros > 30 years ago (Heaney & Heideman, Reference Heaney and Heideman1987) D. chapmani was recently rediscovered (Simmons, Reference Simmons, Wilson and Reeder2005). Most hunters kill only a few bats per trip but those operating at roost sites take hundreds in a single hunt. In Palawan poorer households hunt more frequently, with bats being the target of many hunting trips and harvest rates are high (Shively, Reference Shively1997). Some communities in south-western Negros may collect as many as 300–1,000 bats in a week during the rainy season, amounting to 1,500–5,000 in a summer. A. jubatus has also undergone a dramatic decline as it is both a forest specialist and is heavily hunted (Mildenstein et al., Reference Mildenstein, Stier and Cariño2002). The government now recognizes the threat that hunting poses to wildlife and it has been banned for all but indigenous minorities who use traditional methods, although enforcement is weak. Some local people try to selectively hunt the larger Pteropus species, and others may recognize but ignore population declines. In areas of north-west Panay and Boracay, Frankfurt Zoological Society's Endemic Species Conservation Project (PESCP) has encouraged local recognition of the threats facing wildlife, including bats. PESCP has also successfully reduced hunting through an anti-gun campaign, where firearms can be exchanged for rice or cash. In addition there is a flying fox conservation and monitoring programme, with over 60 groups protecting individual roosts. Dietary studies by Stier (Reference Stier2003) suggest that although bats have catholic diets, A. jubatus prefer Ficus subcordata, and educating hunters to reduce hunting at these fig trees could effectively reduce the take of A. jubatus.

Thailand Bats were eaten by 7% of households in Phu Kheio sanctuary (Magnus, Reference Magnus2001). Some, including the world's smallest species Craseonycteris thonglongyai, may also be dried and sold as souvenirs (Robinson, Reference Robinson1993, Reference Robinson1995). The introduction of foreign aid and improvement in the transport infrastructure in the 1960s meant Rousettus could be hunted in caves in the Bangkok area and traded and sold in restaurants. This resulted in dramatic declines and a drop in guano production such that communities previously economically reliant on it broke up (Stebbings, Reference Stebbings1987). Several species were sold (USD 0.20 each) in the daily market in Chiang Khan, north-east Thailand, sometimes live, impaled through their wings to prevent escape (Robinson, Reference Robinson1994); some may have come from Lao PDR, indicating cross-border trade. In remoter areas, such as villages in Phu Kheio sanctuary, bats may only be sold if a hunter happens to catch a surplus (Magnus, Reference Magnus2001). When limestone quarrying and hunting came close to exterminating Eonycteris spelaea, awareness of their role in the pollination of durian, lobbying by conservationists, and the views of religious leaders who regarded caves as sacred, resulted in legal protection of the main caves and the bats (Stebbings, Reference Stebbings1987). All insectivorous bats and four species of Pteropus are protected by the Wildlife Preservation and Protection Act 1992, although enforcement is weak and roost sites are unprotected. Guano production may also provide an incentive for some communities to try to protect their bats at a local level, although this may not always be successful (Robinson, Reference Robinson1993).

Vietnam Bat consumption is probably less intense than in neighbouring Thailand, especially in the north. Despite extensive surveys into hunting and wildlife trade in Hanoi, only one incident of bat consumption (in Con Cuong district) has been reported. In Kho Muong village in Thanh Hoa Province, bats were collected for food from the local bat cave for 10 days at the beginning of September, with villagers sitting on posts to catch bats using hand-held nets (Thong, Reference Thong2004). Trade or sale of bats in restaurants is generally not recorded in urban areas or in the north but it has been noted in the Mekong region where there are several restaurants selling fruit bats. At least one cave-roost at Hang Doi Kho Muong in northern Vietnam has declined because of hunting (Thong, Reference Thong2004). Bat hunting is the greatest threat to bat populations inhabiting Pu Luong Nature Reserve in north-central Vietnam (Thong, Reference Thong2004). For example, in Kho Muong village local people estimate that c. 1,000 kg of bats were collected from the local bat cave during the annual harvest; the numbers collected declined steadily from 1977 and a recent survey found only a small colony in the cave (Thong, Reference Thong2004). Perceptions of threats posed by hunting vary; some consider it poses a threat to bat populations, whereas others report that harvesting is limited to avoid depleting large colonies and that Miniopterus spp. and Tadarida plicata have been regularly harvested with no observed impact. The Fauna & Flora International Vietnam programme has recorded cave-roosting bat declines in northern Vietnam and is promoting conservation action on this issue and awareness amongst the local people. In Pu Luong Nature Reserve measures to combat bat consumption were recommended by Thong (Reference Thong2004). After the establishment of this reserve, Kho Muong village was requested to end bat harvesting at the local bat cave but recent surveys found few bats inside, indicating either problems with compliance or ineffective management.

East and South Asia

Bangladesh Some tribal people occasionally eat Pteropus giganteus.

China In some areas bats are rarely consumed and always less so than other bushmeat species. In southern China however, bat meat is traded locally and regionally; it appears on some restaurant menus in Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, especially in Wuming County. Bats were seen in markets during surveillance linked to the SARS epidemic in 2003. Bats are not specifically protected in mainland China although proposed tougher wildlife laws, in response to SARS, may ban the consumption of bushmeat.

India (mainland) Bats receive no statutory protection and are classed as vermin (Singaravelan et al., Reference Singaravelan, Marimuthu and Raceyin press). No bat consumption has been observed in Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India, despite extensive surveys that identified the consumption of more than 40 bushmeat species. However, the aboriginal people of remote Indian forests may eat P. giganteus, although in smaller quantities than other bushmeat. Anglo-Indians and aboriginal people regularly eat bat meat in Visakhapatnam and Srikakulam Districts. In India most bat meat is for private consumption.

India (Andaman & Nicobar Islands) Pteropus melanotus and Pteropus faunulus are frequently hunted at night, at their foraging and roosting trees, for consumption on special occasions.

Nepal The Chepang, Newar, Tamang and Bahun Chetri tribes use bats for food.

Pacific Islands

American Samoa There are several reports of consumption of the two fruit bat species Pteropus tonganus and Pteropus samoensis (Cox, Reference Cox1983; Craig et al., Reference Craig, Morrell and So'Oto1994a,Reference Craig, Trail and Morrellb; Brooke, Reference Brooke2001). There are two relevant legislative measures: in 1986 exportation and commercial hunting was prohibited and subsistence hunting limited (Craig & Syron, Reference Craig, Syron, Wilson and Graham1992) and a 3-year hunting ban was initiated in 1992, later extended to aid population recovery after Cyclones Ofa and Val (American Samoa Code Annotated, 1995). However, regulations may be poorly known and enforced (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Trail and Morrell1994b) and export of bats to Guam may continue illegally.

Cook Islands & Niue Bats are regarded as a great delicacy in the Cook Islands, Niue and Mangaia (Krzanowski, Reference Krzanowski1977; Brooke & Tschapka, Reference Brooke and Tschapka2002) and Rarotonga (Wodzicki & Felten, Reference Wodzicki and Felten1980). On Niue fruit bats were hunted in an annual 2-month period that coincides with the bats’ reproductive season (Wodzicki & Felten, Reference Wodzicki and Felten1980; Brooke & Tschapka, Reference Brooke and Tschapka2002). On Niue Brooke & Tschapka (Reference Brooke and Tschapka2002) suggested P. tonganus was overhunted in 1998, when 1,555 were shot by 60 hunters.

Federated States of Micronesia On Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands, although some people may harvest Pteropus mariannus ulithiensis for subsistence use, only a few bats were taken and they were not highly regarded (Falanruw & Manmaw, Reference Falanruw, Manmaw, Wilson and Graham1992).

Fiji Bat consumption is popular with local people and immigrant Chinese. The relationship between hunting and population declines is challenged by reports from Fiji, which suggest that although bats are intensively hunted Pteropus vetulus remains common (Flannery, Reference Flannery1995b). Threats from deforestation are considered more important.

Guam & the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Pteropus meat in Guam is in high demand (e.g. Wiles, Reference Wiles1987, Reference Wiles, Wilson and Graham1992). Its popularity with wealthy residents, as well as preparation methods, are described by Lemke (Reference Lemke1986). The Chamorros, indigenous to the Marianas, consider it a great delicacy and serve it on special occasions (Wiles, Reference Wiles1990), paying up to USD 30 for a single bat (Wiles & Payne, Reference Wiles and Payne1986) despite the fact that eating it may result in a neurogenerative disease (Banack et al., Reference Banack, Cox, Murch, Fleming and Raceyin press). On Guam Pteropus tokudae has become extinct and populations of Pteropus mariannus have declined severely (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Lemke and Payne1989). Many Pacific islands have supplied Guam with fruit bats, including American Samoa, Palau, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines. The decline of fruit bats on Rota, Tinian and Saipan was probably accelerated by harvests to supply Guam's market (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler1980). Wiles et al. (Reference Wiles, Engbring and Otobed1997) reported that 180,000 P. mariannus pelewensis were shipped from Palau to Guam during 1975–1994. In 1989 CITES regulations were amended, with all Pteropus and Acerodon species included in Appendix I or II. The seven most threatened species of Pteropus, including P. mariannus, were placed in Appendix I. These amendments were primarily a response to trade in fruit bats across the Pacific to satisfy demand in Guam. Across this area there are also several pieces of local legislation that aim to regulate fruit bat harvesting or trade. For example, in 1984 P. mariannus was declared Endangered on Guam by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Initially, CITES regulations were not properly enforced but with the arrival of a US Fish and Wildlife Service Inspector, Guam's imports in 1990 dropped from 3,989 during January–March to 292 in May–June (Wiles, Reference Wiles1990). However, imports from other US territories then increased as CITES could not regulate this internal trade. The use of other legislation has been necessary to enforce the trade limitation: for example, the situation in Palau was controlled through application of the Lacey Act that prohibits the inter-state transport of illegally killed wildlife (Wiles, Reference Wiles1990). Loopholes in the law have been exploited, to the detriment of bat populations. In the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands there are special authorizations for bat hunts for two special festivals. However, at these times the quota of 10–15 is exceeded, with hundreds being killed, and there is evidence that bats harvested on Rota may be traded to people on other islands. The small close-knit communities of these islands also make it difficult for local police to enforce this unpopular law (Lemke, Reference Lemke1986). Lemke (Reference Lemke1986) concluded that 75% of fruit bat colonies on Rota had declined, and populations on Saipan had declined to < 25 bats, and on Tinian and Aguijan there were < 10 bats on each island. All three islands supported hundreds, if not thousands, of bats as recently as 10 years earlier.

New Caledonia In the Southern Province bat hunting is allowed only on weekends in April, with a maximum allowed catch of five per hunter per day (Province Sud Nouvelle-Caledonie, 2003).

Solomon Islands About 1,000 bats per month have been taken from limestone cave systems as an alternative protein to fish (Richardson, Reference Richardson1996) and fruit bat is an ‘occasional treat’ on the remote island of Choiseul (Bowen-Jones et al., Reference Bowen-Jones, Abrutut, Markham and Bowe1997).

Vanuatu The 12 bat species are the only native mammals. A questionnaire-based investigation (Chambers & Esrom, Reference Chambers and Esrom1991) reported that fruit bats were eaten by villagers and 85% described them as important in the diet. Only one group did not eat fruit bats, because they regarded them as ancestors.

Western Indian Ocean

Madagascar Pteropus rufus was listed as vermin in 1961. In 1988, after the CITES listing of Pteropus, all Malagasy bats were classed as game and can be legally hunted within a defined season, which is May–October for fruit bats (Durbin, Reference Durbin2007). Despite this, bats are hunted for food throughout the year with both seasonal and geographical patterns of exploitation. There is a small amount of regional trade but most bats are sold locally or are eaten as subsistence food. The extent of hunting of P. rufus has resulted in a recently revised Red List categorization of Vulnerable (Mackinnon et al., 2003; IUCN, 2008; Jenkins & Racey, Reference Jenkins and Racey2008). There is evidence that bat bushmeat is an important source of food for people living with low food security (Goodman, Reference Goodman2006) and that over a dozen species are exploited for bushmeat throughout the island, although one was cooked and fed to pigs (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Ratrimomanarivo, Ranivo and Cardiff2008; Cardiff et al., in press).

Islands & Archipelagos Pteropus subniger became extinct in the Mascarene Islands in the 19th century due in part to overhunting. Although P. rodricensis and P. niger have traditionally been hunted for food on Rodrigues and Mauritius, respectively, they are no longer eaten. As a Critically Endangered species, P. rodricensis is protected, although such protection may be removed from P. niger because of its perceived role in damaging litchi crops. In the Seychelles in the 1970s there was concern about the declining numbers of P. seychellensis, which were hunted for food. However, all guns were then confiscated and bat numbers rose (Racey, Reference Racey1979; Nicoll & Racey, Reference Nicoll and Racey1981). P. seychellensis remains a common item in supermarkets (Hutson, Reference Hutson1997; S. Remie, pers. comm.) and was served by a third of 65 hotels and restaurants surveyed (C. Uzice, pers. comm.). Hutson (Reference Hutson1997) also reported that although consumption was the main threat to bats, populations were still healthy. On the Comoros Islands P. seychellensis comorensis is eaten only occasionally and not by all ethnic groups. The threatened P. livingstonii is less likely to be eaten, because of its rarity and because it is not perceived as so much of a threat to crops (Trewhella et al., Reference Trewhella, Reason, Bullock, Carroll, Clark and Davies1995; Sewall et al., Reference Sewall, Granek, Carroll, Feistner, Masfeiled and Moutui2004).

Sub-Saharan Africa Benin Larger fruit bats, such Eidolon helvum and Epomophorus spp., are preferred and are seen in markets, although they are probably not a regular dietary component. Bats have also been bought in a Togolese market near the Benin border by people from Benin.

Cameroon Consumption of fresh or smoked bat occurs, usually by only a few people or as an irregular component of the diet. E. helvum is a delicacy in the Bomboko area where it can be a major source of income at peak harvesting season, when it is sold for local consumption and to restaurants. Bat meat is traded both locally and regionally. Overall, bat consumption is considered negligible, especially in comparison to other bushmeat.

Congo Republic Most bat meat is hunted for family consumption, although in south-west Congo three of five market surveys conducted by Wilson & Wilson (Reference Wilson and Wilson1991) found E. helvum being traded and eaten at a price lower than any other bushmeat. Bennett Hennessey (Reference Bennett Hennessey1995) also found that fruit bats retailed for a low price in Ouesso, where they are still readily available in markets (R. Ruggiero, pers. comm.).

Côte d'Ivoire E. helvum consumption was observed by one correspondent in the 1980s.

Democratic Republic of Congo In a bushmeat survey in an urban market in Kisangani, Colyn et al. (Reference Colyn, Dudu and Mbaelele1987) made 2,475 observations of E. helvum and Epomops franqueti out of a total of 73,948 observations of all types of bushmeat. E. helvum is abundant seasonally in bushmeat markets in Kisangani and Hypsignathus monstrosus is also sold (Plate 1).

Plate 1 Straw-coloured fruit bats Eidolon helvum (with a single hammer-headed bat Hypsignathus monstrosus in the centre) for sale in the market in Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo (photograph by Guy-Crispin Gembu Tungaluna).

Equatorial Guinea Jones (Reference Jones1972) noted that the only major predator of E. helvum, E. franqueti and Micropteropus pusillus was humans, and Heymans (Reference Heymans1994) also described hunting of E. helvum and Hipposideros spp., although bats were not among the top 35 species preferred by consumers. On Bioko E. helvum and Rousettus aegyptiacus were hunted although they were not the main bushmeat species targeted (Fa, Reference Fa, Robinson and Bennett2000). Fa et al. (Reference Fa, Juste, Perez de Val and Castroviejo1995) and Juste et al. (Reference Juste, Fa, Perezdel Val and Castroviejo1995) showed that bat consumption could occur without trade (Jones, Reference Jones1972), perhaps reflecting the relative unpopularity of bat meat compared with larger mammal species (Heymans, Reference Heymans1994).

Ethiopia The only respondent mentioned bats being heavily hunted because of peoples’ hatred of them, and this may have contributed to local extinctions.

Gabon One respondent reported bat consumption. However, bats are eaten only occasionally and are less popular than other bushmeat species.

Guinea One respondent noted that all species of bats are hunted in caves for consumption on special occasions, although no bat consumption was noted by Fahr & Ebigbo (Reference Fahr and Ebigbo2003). Fahr et al. (Reference Fahr, Vierhaus, Hutterer and Kock2002) noted that cave roosts of Rhinolophus maclaudi in Upper Guinea were ‘increasingly exploited’ and R. ruwenzorii roosting in caves were vulnerable to exploitation. Entire populations of cave-dwelling bats could be killed in one visit. Although hunting is carried out only twice per year a detrimental impact on bat populations is likely.

Liberia E. helvum is regularly consumed and traded but they are the lowest priced item and constituted only 0.25% of items recorded at market (Anstey, Reference Anstey1991).

Mali There is one report of bat consumption at Solo village, near Manantali Dam, in Mali.

Nigeria Bat consumption seems widespread and Folorunso & Okpetu (Reference Folorunso and Okpetu1975) published recipes for fruit bats. Halstead (Reference Halstead1977) described the harvest of E. helvum at the University of Ife, Nigeria; bats were shot on a weekly basis over October–March, with approximately 12,000 shot in a season. No more than 600 bats were taken in any one shoot and there was no apparent impact on the colony. Controlled hunting appeared to allow the colony to grow, possibly because of the lessened disturbance and harassment of the bats. Adeola & Decker (Reference Adeola and Decker1987) found E. helvum was harvested by rural farmers during the rainy season. Bats were a cheap meat, popular with women from Ife and surrounding areas.

South Africa There appears to be little bat consumption in South Africa although occasional hunting of the small but common Rhinolophus spp. may occur in the Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces.

Tanzania (Pemba) Although bats are not consumed in mainland Tanzania bat meat is popular on the island of Pemba (Entwistle & Corp, Reference Entwistle and Corp1997). There are four fruit bat species and Pteropus voeltzkowi is endemic. It is considered a delicacy and is particularly prominent in the diet in June–July (Entwistle & Corp, Reference Entwistle and Corp1996). Entwistle & Corp (Reference Entwistle and Corp1997) found no evidence that bats were sold but were rather distributed among members of a hunting party for private consumption. Seehausen (Reference Seehausen1991) described the dramatic decline of P. voeltzkowi, comparing past reports of large colonies with the small groups seen in 1989, and attributed this to increasing intensity of hunting as well as habitat destruction. Entwistle & Corp (Reference Entwistle and Corp1997) found hunting was widespread throughout Pemba, occurring at 13 of 19 occupied roost sites, with signs of recent hunting at five deserted roosts. An education programme led one village to protect their flying fox roost and the number of bats at this roost then apparently increased to become one of the largest on the island (Entwistle & Corp, Reference Entwistle and Corp1996). The expansion of this education programme through Environment Clubs has resulted in a decline in hunting and an increase in bat numbers to an estimated 21,000 (S.J. Ali, S.K. Haji & F.M. Saleh, pers. comm.; Robinson, Reference Robinson2008).

Uganda There was local demand for E. helvum when they were sold at Makerere University in Kampala after a storm blew them to the ground (Ogilvie & Ogilvie, Reference Ogilvie and Ogilvie1964). However, numbers of E. helvum there declined from 250,000 to 40,000 in 40 years (Monadjem et al., Reference Monadjem, Taylor, Cotterill, Kityo and Fahr2007). This species, along with others, is eaten by the Bagisu people in eastern Uganda, where bats are hunted for private consumption.

Zambia In western Zambia local people eat E. helvum (C. Kandunga, pers. comm.).

South America

Despite the diversity and abundance of bats across tropical America the majority of reports suggest bat consumption is rare. However, a perception of bats as being dangerous can lead to their being hunted with the aim of exterminating populations. There is one report of regular bat consumption by some native tribes, most notably the Nambiquara of western Brazil, who consume three species of phyllostomids (Lévi-Strauss, Reference Lévi-Strauss1979; Setz & Sazima, Reference Setz and Sazima1987; Setz, Reference Setz1991). In Brazil all native species are legally protected but bats have traditionally been regarded as dangerous and have been exterminated in many areas.

Discussion

This review presents clear evidence that bat populations are seriously threatened by hunting for bushmeat in several countries, particularly Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, and several islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Unsurprisingly, the main target species are fruit bats of the genus Pteropus because they are the largest, roost in trees and forage on flowers, leaves or ripe fruit, so that their whereabouts are predictable. Reported levels of offtake in species with such a low reproductive rate is a matter of serious concern. In those mainland African countries in which bats are hunted, it is also the largest fruit bat species, E. helvum, that is targeted, and population declines have also been reported. Although bat faunas are richer in Central and South America the constituent species are small-bodied and there is little to suggest that hunting is widespread or is having a significant effect on populations.

Legislation to protect wildlife in the developing world is seldom effective by itself because of the difficulties of enforcement, and other approaches are necessary. However, national legislation to protect bats is preferable because its absence in some countries, such as India, where bats are classed as vermin, inhibits conservation action at some levels (Singaravelan et al., Reference Singaravelan, Marimuthu and Raceyin press). Occasionally, the control of guns and ammunition has proved effective in preventing population declines of bats hunted for food, as in the Seychelles. Education programmes that emphasize the role of bats in providing ecosystem services are now widely implemented (Trewhella et al., Reference Trewhella, Rodriguez-Clark, Corp, Entwistle, Garrett and Granek2005; O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Riger and Jenkins2006, Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Andriafidison, Razafimanahaka, Rabearivelo, Razafindrakoto and Andrianandrasana2007). Local communities often resent commercial hunters from outside the community taking bats from their neighbourhood, and community conservation programmes have proved particularly effective in Pemba and Madagascar. The most pressing requirement is for research into sustainable harvesting, particularly because the only managed harvest reported to date, that organized by Halstead (Reference Halstead1977) in the campus of Ife University, Nigeria, appeared to have been effective. Voluntary controls of hunting in New Guinea (Cuthbert, Reference Cuthbert2003b) and Madagascar (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Andriafidison, Razafimanahaka, Rabearivelo, Razafindrakoto and Andrianandrasana2007) have also been successful in halting declines in bat numbers.

The provision of reliable data on changes in population size, to measure the impact of hunting, requires well-designed monitoring programmes, which are particularly challenging to implement for bats forming large aggregations and moving between roosts. Where such long-term programmes are established, as in Uganda (Monadjem et al., Reference Monadjem, Taylor, Cotterill, Kityo and Fahr2007), they have documented declines that are seldom dramatic from year to year but over longer periods become a matter of serious concern. Similar monitoring programmes have been in operation over shorter periods in Madagascar (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Andriafidison, Razafimanahaka, Rabearivelo, Razafindrakoto and Andrianandrasana2007). Long-term monitoring programmes are difficult to sustain in the tropics but are clearly needed.

Considering the widespread nature of hunting, there have been few studies on the relative importance of bats in the diet, i.e. to determine the extent to which it is an expensive luxury reserved for special occasions, as with the Chamorro on Guam, or adds variety to a diet that is not protein deficient. Elsewhere it may be a starvation food, as in south-west Madagascar (Goodman, Reference Goodman2006). Bat consumption driven by preference, rather than need, may require different interventions if conservation is to be successful.

The threat of pathogen transfer from bats to people is of growing concern. The discovery of asymptomatic Ebola virus infections in three species of pteropodids in West Africa (Leroy et al., Reference Leroy, Kumulungui, Pourrut, Rouquet, Hassanin and Yaba2005) raises concerns about the risk to humans of preparing bats for consumption. Appropriate surveillance for the presence of disease should be carried out before sustainable harvesting programmes are encouraged.

In conclusion we recommend: (1) Continuing surveys of the extent to which bats are taken as bushmeat and the incorporation of bats in surveys of general bushmeat consumption, recognizing that the supply chain for bat meat may differ from that for other bushmeat; these surveys should also evaluate the relative importance of bat bushmeat in the diet and the possible health risks of bat consumption. (2) Where none exists, national legislation should be introduced to protect bats or establish closed seasons for hunting, depending on the conservation status of the species concerned. (3) More education projects aimed at publicizing the importance of bats as pollinators and seed dispersers, and their role in forest ecology. (4) More community-based projects aimed at conserving local bat populations or, where appropriate, harvesting them sustainably.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of those who provided information for this review. Their names and geographical areas of expertise are listed in Appendix 2. We would also like to thank Richard Jenkins, Steven Goodman and an anonymous referee for comments on earlier drafts and Nora Morrison at the University of Aberdeen for help in the production of the final manuscript.

Appendices 1–2

The appendices for this article are available online at http://journals.cambridge.org

Biographical sketches

Simon Mickleburgh has been involved in bat conservation at a national and international level since 1984, and co-authored the two IUCN action plans on bats. Kerry Waylen is concerned with improving conservation outcomes in developing countries, using both socio-economic and biological knowledge. She is currently carrying out research on the evaluation of community-based conservation projects. Paul Racey has worked on the ecology, and reproductive and conservation biology of bats for over 40 years. He is Vice Chairman of Fauna & Flora International and Co-Chair of IUCN's Chiroptera Specialist Group.