1. INTRODUCTION

In 1972, the British composer and inventor Daphne Oram published An Individual Note of Music, Sound and Electronics. In the penultimate chapter, which gives a brief history of electronic music from 1946 to the 1960s, she writes:

Do not let us fall into the trap of trying to name one man as the ‘inventor’ of electronic music. As with most inventions, we shall find that … many minds were, almost simultaneously, excited into visualising far-reaching possibilities. New developments are rarely, if ever, the complete and singular achievement of one mind … I wonder why we want so much to see one man as the hero of the occasion. (Oram Reference Oram1972: 111)

Oram’s words are quoted by Tara Rodgers in her essay ‘Tinkering with Cultural Memory: Gender and the Politics of Synthesizer Historiography’. The ‘hero of the occasion’ that Rodgers refers to is Robert Moog. Rodgers draws attention to the clichés of white masculinity that abound in historical accounts of Moog – ‘canonized’, as she puts it, as ‘Bob’, the ‘humble tinkerer’ who revolutionised music technology from his basement (Rodgers Reference Rodgers2015: 13–14). She goes on to describe her discovery of a collection of letters between female electronics enthusiasts and the lead developer of the RCA synthesiser in 1956, demonstrating how long-held assumptions around gender and music technology can be challenged by attending to previously unexplored aspects of its history and by shifting the focus from individual innovators to less well-known participants.

These participants are by no means solely women. As Rodgers’s account also makes clear, class, educational and economic status as well as gender identity are important factors to consider when reading and writing electronic music histories. This concern can be seen in the work of, for example, Ian Helliwell, an independent researcher and filmmaker who has explored and rehabilitated the music of working-class British inventors and technologists such as Fred Judd and members of the UK’s amateur ‘tape clubs’ (Helliwell Reference Helliwell2016); and Sean Williams, whose practice-led research interrogates the role of the performance technicians who helped realise Stockhausen’s compositions (Williams Reference Williams2016).

However, in recent years, numerous articles, recordings, artworks and concert programmes have addressed the issue of women’s involvement in the history of electronic music. While much of this work seeks to challenge dominant narratives, redress a historical imbalance and forefront the work of important composers, musicians and technologists, it risks perpetuating another dominant narrative, that of the lone, exceptional female ‘pioneer’, which casts figures such as Oram in the heroic role that she warned against in 1972; this narrative serves to elevate a small number of women to the same stature as their male counterparts. Meanwhile the visual primacy of online media encourages the formation of certain tropes which have come to represent the complex issue of women’s involvement in electronic music and sound: first, data and infographics, and second, the archive photograph of a woman using historical music technology. Not unrelatedly, through reissues of archival works and their coverage in the media, the pioneers narrative helps to generate more revenue for both independent record labels and large media corporations.

The narrative of the exceptional, pioneering woman and its visual presentation have not gone unnoticed: along with Rodgers’s essay, it has been commented upon by writers including Annie Goh (Goh Reference Goh2014) and Abi Bliss (Bliss Reference Bliss2013). In this article I continue the critique of what I will call the pioneers narrative in relation to its appearance in new media discourse and digital visual cultures. For the purposes of this article I have taken this discourse to include magazines, social media, record labels and websites, recognising that the term ‘website’ can mean many things; for example, a Tumblr blog hosted by an individual sharing images from around the web; a web-based artwork made by a digital arts collective; and Red Bull Music Academy Daily, the online publication initiative of the Red Bull Music Academy are all websites.

In critiquing the pioneers narrative, I draw on feminist musicology and digital media theory, suggesting parallels with contemporary research on structures of race, gender and class in histories of software and computing. I propose that exploring these disciplines may be fruitful in a number of ways for historians of electronic music, not only in helping us analyse the media via which electronic music histories are increasingly transmitted and received, but also in presenting some potential alternative frameworks for how the complex historical relationships between gender, technology and cultural production might be read and written.

2. ‘10 FEMALE ELECTRONIC MUSIC PIONEERS YOU SHOULD KNOW’

It is pertinent to ask why researchers into histories of electronic music should concern themselves with articles that have headlines such as the one above, when the discourses of online journalism and academic research are intended to fulfil different purposes and are directed towards different audiences. However, although it is beyond the scope of this article to carry out an extensive analysis of the relationship between the media coverage of and academic research into electronic music, I assert that print and online media play a role in making visible certain aspects of electronic music history to readers who might also be practising musicians, music scholars and potential researchers. This is not to say that there is an equivalence between, for example, an interview with Suzanne Ciani on the Red Bull Music Academy website (Bächer Reference Bächer2015) and a doctoral research project about her work, but it is not unreasonable to suggest that a student of musicology embarking on such research might first have encountered Ciani via such an interview, or via the Feminatronic Twitter feed (twitter.com/feminatronic), or a Facebook group such as Women in Electronic Music (facebook.com/wemusic/).

Academic writers and researchers exploring the relations between gender, sound and technology increasingly use the same platforms as commercial music media to discuss, promote and present their interests, using social media such as Facebook and Twitter and publishing in online journals such as Sounding Out! (a Sound Studies publication which is peer-reviewed but independently and collectively run), in popular music publications such as The Wire and The Quietus, or on their own personal websites. To give one example, philosopher and musicologist Robin James uses a Blogspot-hosted blog (its-her-factory.com) and a Twitter feed, as well as having published articles on the popular music website Noisey. James writes about popular music from a critical race and gender perspective, and her multiplatform approach acknowledges the significance of all kinds of media in shaping ideas of race and gender in relation to music and sound.

While this article concerns historical narratives of electroacoustic music rather than popular music cultures, I hope to show how these are intertwined in contemporary media discourse around electronic music history; for example, in the popular notion of a lineage stretching from composers such as Delia Derbyshire to modern-day techno musicians (Blanning and The Black Madonna 2015). Historians of electronic music made by women should be alert to how this discourse is generated and maintained in areas such as social media and online journalism. Tara Rodgers writes:

That these lists [of female pioneers] are a recurring and highly visible Internet phenomenon functions as a mode of constraint on imagining the place of women in electronic music history. (Rodgers Reference Rodgers2015: 9)

If this is the case, then it is important to look more closely at the media which create that mode of constraint.

In a recent paper on the history of EMAS (the Electro-Acoustic Music Association of Great Britain) that focuses on the gender diversity of its makeup during the 1970s and 1980s, Simon Emmerson reflects on the climate in which EMAS was set up compared with the present day, writing:

The year EMAS was founded there was plenty of sound art installation, free electronic improvisation, DIY and noise. But there seems since to have been a reconfiguration of the presentness of these practices – their increased legitimation through the cultural capital of promotion, as well as greater coverage from academic writing and popular journalism in broadcast, print and new media forms. (Emmerson Reference Emmerson2016: 29)

Here Emmerson is concerned with the ‘increased visibility’ (his emphasis) of those practices which are more likely to attract a diverse range of artists; and thus, potentially include more women. Emmerson’s recognition of the media’s role in this process is insightful. If there are still significant differences between the areas of sound and music that Emmerson lists, the media discourse around them serves to blur their boundaries. This, in turn, broadens the definition of electronic or electroacoustic composition to include a range of practices, philosophies, and educational and professional backgrounds. We could see media coverage of female pioneers of electronic music in an equally positive light, for it not only forefronts under-recognised women’s work but also implicitly supports these broader categories of electronic music in placing composers, performers and technical innovators in unusual conjunction. Yet it is not necessarily the case that articles such as the one whose headline I have borrowed for this section invite us to draw useful connections between those women’s work other than the fact of their gender, or help to situate them in historical contexts. What, then, is their purpose? Looking again at the article entitled ‘10 Female Electronic Pioneers You Should Know’ (Hawking Reference Hawking2012), I will sketch out some of the characteristics of such articles, in an attempt to understand the political and commercial aims behind such projects.

3. WOMEN AND/AS DATA

A Google search for ‘women electronic music pioneers’ produces nine pages of headlines similar to the one above, which is taken from an article on the Flavorwire website, published in 2012. It demonstrates three characteristics that are typical of such articles. First, the list is presented as numbered entries that the reader can either scroll or click through. Second, each entry features a short paragraph of text accompanied by a large, embedded YouTube video which is used primarily as an audio stream but, in most cases, also shows an image of the woman in question (others use a large, non-hyperlinked image with a separate YouTube or Soundcloud embed).Footnote 1 Third, there is an emphasis on the language of exceptionalism and winning: composers are ‘at the forefront’, ‘the first’, ‘pushing the sonic envelope’ and making music that’s ‘ahead of its time’. Another defining characteristic is the selection of names, which at first appears to demonstrate the kind of pluralism noted by Emmerson (Reference Emmerson2016). For example, the Flavorwire article features the BBC Radiophonic Workshop composers Delia Derbyshire and Daphne Oram, Lithuanian-born Theremin player Clara Rockmore, North American composers Pauline Oliveros, Laurie Spiegel, Bebe Barron (co-composer of the Forbidden Planet soundtrack), Wendy Carlos and singer/composer Annette Peacock, as well as Laurie Anderson (also from the United States) and German artist Gudrun Gut, who are associated with performance and multimedia art and post-punk music rather than composition in the traditional sense.Footnote 2

But this list, while varied stylistically, is not necessarily diverse. It presents a European and North American history that begins in the 1950s and 1960s with soundtrack and sound effects composition, is clustered in the 1970s around practitioners of analogue synthesis and early computer music, then converges again in the experimental culture of the early 1980s. While some of the composers mentioned have of course been active up until the present day, so cannot literally be regarded as ‘from the 1970s’, it is clear that figures who emerged in the later 1980s and 1990s are barely represented. The Vinyl Factory’s timeline, ‘The Pioneering Women of Electronic Music’ (Ediriwara Reference Ediriwara2014; see also Figure 1), shares this chronological bias, claiming only two women as ‘pioneers’ in the 1990s. The 2000s is represented by Björk and The ADA Project, a performance installation created by artist Conrad Shawcross, which celebrates the legacy of Ada Lovelace with robotic sculptures programmed and ‘responded to’ by four female artists (in fact, two solo female artists and two male/female duos) (Spice Reference Spice2014). The Vinyl Factory, which is positioned somewhere between a record label and a media production company, presented the project in its exhibition space. The timeline is thus used to provide a historical framework for their project, inviting viewers to see it as part of a continuum of women working with music technology.

Figure 1 Vinyl Factory, The Pioneering Women of Electronic Music: An Interactive Timeline. Reproduced with permission of The Vinyl Factory.

In these presentations we can see that our female pioneers are arranged either in lists or graphically on a timeline. The format of the Flavorwire article, in which the reader has to click on or scroll to each entry to see it, encourages us to see these composers as lone operators; the Vinyl Factory timeline, although it initially presents a fuller, less individuated picture, presents women as isolated points on a graph, not allowing the viewer to make any connections between them other than chronological ones. In these formats, the wider context of broadcasting, national and university-based studios in which electronic composers of this time were likely to be based, is downplayed and the possibility of exploring other networks, collaborations, grassroots feminist activities, and the presence of lesser known figures who contribute to these structures, as Rodgers’s letter-writers contributed to the history of the RCA synthesisers, is much reduced. Among the composers selected there is a bias towards tape music and the early days of synthesiser technology, and a strong concentration of white, Euro-American identities.Footnote 3 We start to get a sense not only of what constitutes ‘pioneering women in electronic music’ but also of electronic music itself, and the historical conditions required to see it as ‘pioneering’.

The concentration of European and North American composers active in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s in these articles and infographics is not unexpected, nor is it inaccurate: this period saw key technological and aesthetic developments take place across Europe and the United States, along with various post-war initiatives, such as the building of public studios, that supported experimental sound and music practice. With greater empirical evidence of their participation now available, the role of women as pioneers in this period of history is becoming more widely acknowledged. Yet in celebrating this we should not lose sight of why and how they were absent in the first place. The pioneers narrative, even as it appears to correct a historical imbalance, risks recapitulating to heteropatriarchal structures into which a small number of exceptional, ‘visionary’ women have been admitted, instead of asking why those structures allowed, and allow, for so little difference, or proposing new models of historiography that would, as Tara Rodgers writes, challenge the ‘patrilineal history of electronic music production’ (Rodgers Reference Rodgers2010: 15). The patrilineal history can also be read as an imperialist one: we might wish to challenge the North American focus of this narrative, for example, when histories of electronic music in South and Central America are increasingly well documented, and include women such as Argentine composers Nelly Moretto and Hilda Dianda (Holmes Reference Holmes2015: 139–41).

The absence of women in patrilineal histories should be understood not as an effect of certain composers being ‘forgotten’, as if this is an accidental oversight, but as a symptomatic lack of recognition during the time in which many of those now cited as pioneers were at their most active. Looking at an early and well-known survey of electronic music, Paul Griffiths’s A Guide To Electronic Music (Griffiths Reference Griffiths1979), we can consider how the structures in place around composition, publishing, recording and distribution of music have contributed to this absence. Griffiths lists no recordings by female composers in his book’s ‘Recordings’ section, and only one woman, the singer Cathy Berberian, appears in the index. Griffiths’s sources for the book appear to consist mostly of musical works published and recorded by established publishers and record labels. Despite the many issues of authorship, autonomy and collaboration raised by electronic music, in which works do not often lend themselves to traditional methods of scoring, performance and analysis, Griffiths adheres to an idea of the autonomous musical work that excludes a large proportion of electronic music practice. This decision, of course, is in part a practical one in the pre-internet era: then as now, readers wish to be able to access the music that they have read about. But it has the result of erasing those who were not widely published or recorded – if indeed they were published or recorded at all – or whose achievements were focused more on technological innovation, collaboration, improvisation, performance, education and other less orthodox areas; from their absence in accounts such as Griffiths’s, we can surmise that a disproportionate number of the people who worked in these interstitial, more ephemeral areas were women.

An increasing amount of scholarship aims to address this exclusion by exploring the electronic music made by women through different methodologies and viewpoints. Tara Rodgers’s Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound (Rodgers Reference Rodgers2010) is a key contribution to our understanding of the history of electronic music, profiling important practitioners as well as analysing dominant historiographical models. Louise Marshall’s current research into composers including Eliane Radigue, Laurie Spiegel and Pauline Oliveros addresses their work ‘within the dominant hierarchies’ of twentieth-century music, exploring ‘the innovation and collaborative techniques that they had to utilise in order to negotiate their relationships with those structures’ (Marshall Reference Marshall2016), using methods from psychology as well as oral history practice. The research by Holly Ingleton into the curatorial project Her Noise is likewise concerned with feminist process and strategies in electronic music and sound arts, as well as feminist approaches to archives and histories of sound and music (Ingleton Reference Ingleton2015). In her recent writing, she draws on feminist historian Joan W. Scott’s idea of the ‘resistance of history’ to describe the difficulties and shortcomings of attempts to write women into musical histories, and to propose a self-reflexive critical practice ‘that interrogates the connections between the social and the political and the conflictual processes and forces by which meanings are established’ (Ingleton Reference Ingleton2016). Meanwhile Sounding Out, Martha Mockus’s (Mockus Reference Mockus2007) study of Pauline Oliveros in the context of a ‘lesbian musicality’ situates Oliveros in a history of queer art-making, domesticity and community that is often overlooked in media representations of her electronic composition – it certainly does not fit with the image of the lone, studio-bound pioneer.

We might also consider the recent interest from scholars, musicians and archivists in the work of Daphne Oram, who at the time of her death in 2003 was almost completely unknown. She has since been acclaimed not only as a composer of interest but also as an innovative technologist, whose optical ‘Oramics’ synthesiser has been said to prefigure later developments in computer music (Grierson and Boon Reference Grierson and Boon2013: 185–201). In this reading, the focus is less on Oram’s published or recorded works, and more on her role as a conceptualist and innovator, highlighting the inclusive potential of an object-focused material cultures perspective in histories of electronic music. This coincides with a growing body of literature on important studios, with notable studies of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (Niebur Reference Niebur2010) and Stockholm’s EMS (Groth Reference Groth2015), to name two, drawing attention away from exceptional, heroic and easily represented figures and to the frequently collective, and to varying degrees diverse, environments of electronic music’s historical conditions of creation.

We can see, therefore, that an approach based on a survey of published or recorded works has not historically served electronic music made by women well, compared with new approaches that depend less on the status of the published and recorded work. The increased availability of archival material that challenges the official narrative of the record release or published score, plus the means to present it in imaginative, innovative ways using digital platforms, along with a growing acceptance of feminist, queer and other critical perspectives, foster a positive environment for such approaches. Yet today’s new media accounts of women in electronic music, rather than using those media to explore new ways of presenting women’s histories, still rely heavily on the existence and accessibility of autonomous musical works as an indicator of the composer in question’s status. This entrenches the idea of women’s music as lesser, because there is literally less of it to access, and therefore of only minor or niche interest to scholars – or of cult interest to collectors. This last factor neutralises, even makes desirable, the historical absence of women, turning the rarity and ‘lostness’ of their music into commodities, and the occasion of their ‘rediscovery’ as celebratory, rather than an indictment of their previous exclusion.

In the section below, I consider how quantitative representations of female composers contribute to the establishment of ‘music made by women’ as a genre, intended for a specific listenership.

4. GENDER AS GENRE

Projects of retrieval and reclamation have played a key role in the formation of feminist musicology, with interventions such as Diana Peacock Jevic’s Women in Music: The Lost Tradition Found and many others changing historical perceptions of women’s compositions (Peacock Jevic 1989). The objectives of such projects are outlined broadly by Sally MacArthur in Towards a 21st Century Feminist Politics of Music: ‘to recover [composers’] names and their music, and to introduce them to the concert hall, to music institutions of learning and to the pages of mainstream music history’ (MacArthur Reference MacArthur2010: 2).

In MacArthur’s analysis, the ideologies driving all such work are reflected in how this recovered or gathered information is used: whether to build new canons or histories, or to address inequalities in the present day. These ideologies can be seen in different methodologies as well as in more explicit connections to schools or ‘waves’ of feminism. MacArthur gives a useful account of what she calls a positivist approach, typical of liberal feminist politics,Footnote 4 in which data are used to show either high or low numbers of female participants in a particular setting. Commenting on a study by Patricia Adkins Chiti (Reference Adkins Chiti2003) which surveys the percentage of music by women composers that is performed in concert throughout Europe, she writes, ‘the research is couched in a neoliberal version of agency. It imagines that women’s music will be included in orchestral programmes if the research exposes, opposes and resists the power of the oppressors’ (MacArthur Reference MacArthur2010: 27).

MacArthur makes a compelling case against relying too heavily on positivist, empirical research frameworks, or on the patterns supposedly revealed by their results, asserting that such a framework ‘produces thinking which forecloses thought’. She continues, ‘It reduces the object of study – the woman composer and her music – to an immutable, negative image’ (ibid.: 33). She goes on to employ Rosi Braidotti’s concepts of ‘gender-mainstreaming’ and the ‘master-narrative’ to critique the celebration of exceptional women that can result from a positivist approach. Gender-mainstreaming, when gender is ‘central to all the activities of an organisation and its policies’ (ibid.: 79), is ‘a classic master-narrative that is pro-capitalist’ (ibid.: 80), focusing on material and financial success, MacArthur writes. Citing Braidotti’s Transpositions (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2006: 45), MacArthur states that, ‘gender-mainstreaming reintroduces the syndrome of the “exceptional woman”’, with which it works in tandem to foster ‘a new sense of isolation among women and hence new forms of vulnerability’ (MacArthur, Reference MacArthur2010: 80)

Attempting a transposition of my own, I propose that the historical narrative of the female electronic composer is likewise subject to gender-mainstreaming, especially – although of course not only – in media accounts of female pioneers. The pro-capitalist aspect of gender-mainstreaming of which Braidotti writes can be seen here in the mutualist relationship between the pioneers narrative and the growing body of archival recordings of electronic works by women, now a profitable niche within the independent record industry.

With the growth of digital audio and high-speed internet services, the independent record industry’s model for disseminating music has shifted from mass-produced physical products to downloaded or streaming digital audio; its means of marketing, too, have changed, relying on social media, blogs and the quasi-promotional written content produced by online music platform Bandcamp, among others, as well as on more traditional print and web magazines. Faced with a loss of revenue from music sales, independent record labels have responded to these changes first by redefining physical media such as the vinyl record as an attractive, often costly and limited edition artefact (usually sold along with a download code for the digital version); and second, by participating in an ongoing archival turn which has seen labels previously known for releasing new music adding both reissued albums and previously unreleased archive recordings to their roster, and new niche labels and imprints being set up specifically for this purpose. For example, Recollection GRM, set up solely to release remastered material from GRM’s archives as limited edition vinyl records, is an imprint of the label Editions Mego.

This gives us an idea of how the two factors of increased access to digital (or soon to be digitised) audio archives and increasingly niche marketing of this material has created a discourse around rarity, rediscovery and re-presentation of artefacts from electronic music history.Footnote 5 Within this discourse, the feminist project of retrieving women’s music and exploring the conditions of its making has been mainstreamed and reified, taking on the characteristics of a genre. In September 2016, the online music retail site Boomkat described a new limited edition vinyl release of electronic music made in the 1970s by Italian composer Teresa Rampazzi: ‘an indispensible, crucial artefact if you’re interested in the recordings of Daphne Oram, Tod Dockstader, Eliane Radigue or Delia Derbyshire’.Footnote 6 Here Rampazzi is reified not only through the ‘artefact’ that contains her music – which is described as, ‘Housed in a gorgeous foil-blocked metallic print jacket with fold-out insert of liner notes and photographs’ (ibid.), but also her placement within a predominantly female group of names. Boomkat originated as a dance music retailer, and here we see the application of ‘micro-genres’, used in dance culture to define music by small differences of rhythm or tempo, to both gender and chronology. Yet it is important to point out that this process is not always wholly one of the co-option of feminist research by the record industry. In this instance the liner notes are written by musicologist Laura Zattra, who is credited as the ‘curator’ of the record release, and who is engaged in ongoing research into Italian post-war electronic music, focusing on the work of women composers.Footnote 7

The relationship of this archival strand of the music industry to the media discourse around female pioneers in electronic music can be seen in how contingent lists and articles such as the ones cited in this article are on the availability of audiovisual clips which can be embedded in text. As more records are released and more audio uploaded onto YouTube and Soundcloud, we can expect that the names in the list will change. For example, Teresa Rampazzi is rarely included in female pioneer lists, but were I a journalist making one today, I might be more likely to include her – not only because I would be keen to show that I can add a new name to the conversation, but also because the aforementioned album of her work has recently been released on Die Schachtel records, allowing me to use a Soundcloud clip to illustrate the entry.Footnote 8

Because it ostensibly costs the web user nothing to view and upload videos, YouTube promotes an idea of shared ownership and creative freedom for both creators and viewers. However, like other successful online platforms such as Facebook, YouTube uses sophisticated algorithms to present viewers with content they might be interested in, which provides valuable data for advertisers, whose revenue and partnerships fund the site. The more a YouTube video is shared, the more it will be circulated, and the more likely it is to appear on the sidebar that recommends the viewer’s next video. Thus, our notions of electronic music’s pioneers are produced and reproduced at least in part by definitions of taste generated and shaped by the algorithms of a media corporation; and those who do not embrace those platforms, or are not embraced by those who embrace those platforms, are less likely to feature in accounts of important, pioneering musicians.

5. DIGITAL MEMORIES

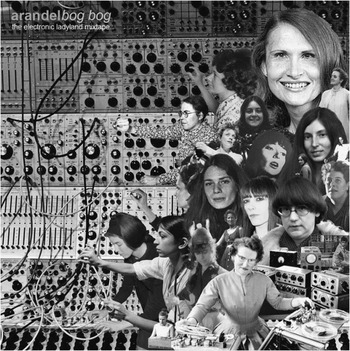

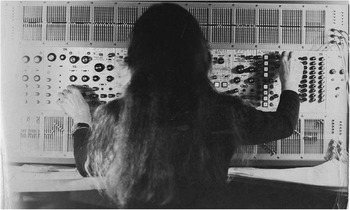

In new media narratives of female electronic music pioneers our screens show an abundance of black-and-white archival images of women in studios working with tape or synthesisers (Figure 2). In literal terms, then, women in electronic music seem to be more visible than ever. But the notion of visibility – which encompasses both identity and representation – as an indicator of political progress is problematic, not least because most online media demands and depends on visual material to represent music and sound, thus making it an imperative that if one’s work is to be audible, it must first be, in some way, made visible. As more and more images vie for our attention on multiple devices, it is not surprising that the images that come to represent the female electronic music pioneer are ones that can be instantly recognised and interpreted as showing ‘woman’, ‘history’ and ‘electronic music’, resulting in a set of limiting visual markers.

Figure 2 The cover of a digital compilation produced by electronic music producer Arandel. www.infine-music.com/news/374/podcast-024-arandel. Reproduced with permission of InFiné Music and Arandel.

Some theorists of digital culture query the boundaries and hierarchies of image and sound when both are composed of data. Media theorist Wolfgang Ernst, writing about sound archives, claims that the processes of ‘unfreezing’ and transferring sound into new formats render the distinction meaningless, as ‘digital memory ignores the aesthetic differences between audio and visual data and makes one interface … emulate another’ (Ernst Reference Ernst2011: 248). Ernst’s claim is rooted in a media archaeological discourse, which forefronts a close reading of the media object as opposed to constructing a linear narrative of historical-technological progression. It encourages us to think beyond content, and perceive digital images and sound instead as objects and structures. Tara McPherson likewise proposes, when writing on the politics of the internet, that we should extend this discussion beyond issues of access to computers or broadband, and beyond ideas of identity and representation. These, she writes, ‘can risk remaining on the surface of our screens and make it harder to see the vast systematic chances unfolding around and enveloping us’ (McPherson Reference McPherson2014: 163). McPherson, however, diverges significantly from Ernst in her commitment to considering the political implications of digital media’s structures, claiming that, ‘Technological systems never exist outside of culture’ (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2015).

We have also seen, in reference to Daphne Oram, how material culture-based research, which focuses on the relationship between objects and the people using them, opens up possibilities for writing new and more inclusive histories of electronic music. In this context, images of musicians using technology have a clear value to the researcher. Meanwhile, in both composition and performance, music technology has suggested countless new, potentially subversive ways in which gender can be performed, as Sally MacArthur writes of a young electronic composer who performs with a laptop, ‘Not only is the dualistic construction of subjectivity dismantled such that the composer’s body recedes into the background, but the technology is put to work to dissolve the boundaries erected around music itself’ (MacArthur Reference MacArthur2010: 160).

Yet the digitally processed archival images of gendered bodies with machines that illustrate the female pioneers narrative can provoke a particular disquiet, intensifying boundaries rather than dissolving them. In a review of a CD set of Pauline Oliveros’s early electronic works, Nina Power, while acknowledging Oliveros’s creative freedom with electronic sound, is reminded of the other ways in which women have been paired with technology in the twentieth century, a history, she writes, ‘of women working efficiently and methodically at switchboards … of the hidden fantasies of the mechanised woman of Metropolis; of the machine and the woman, and all the work that we tend to forget, or celebrate only for kitsch value’ (Power Reference Power2012: 57).

Tara Rodgers also alludes to this history of women’s work when she considers how the RCA synthesiser could have been marketed to women, proposing that:

the technology and associated techniques of the synthesiser patch, the configuration of wires that assemble component elements of a sound into one signal, was inherited from telephone operating – a profession thoroughly associated with women as a labour force and in popular culture. (Rodgers Reference Rodgers2015: 20)

The visual and gestural resonances between music and labour noted by Rodgers and Power amplifies the discrepancy between an imagined but unrealised future of music-making for women, embodied both by exceptional figures such as Oliveros and the female electronics enthusiasts discovered by Rodgers and by the reality of most women’s historical experiences with technology in the workplace, rather than as a site of creativity. This is, of course, not only a historical narrative but also one that continues into the present day, as women now represent a substantial proportion of the workforce that assembles computers and other digital devices. With this in mind, it can be argued that the liberatory potential for the female performer that MacArthur (Reference MacArthur2010) sees in the laptop is achieved at the expense of those whom ‘transnational capital exploits to create the machinery for this so-called autonomous zone’ (Hess and Zimmerman Reference Hess and Zimmerman2014: 184).

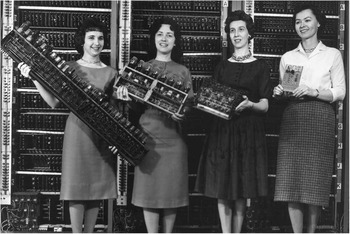

A reading from the histories of computing helps us to understand something of the complex, non-linear nature of histories of gender and technology, and the role of the archival photograph in both illuminating and obscuring those histories. In Programmed Visions: Software and Memory, digital theorist Wendy Hui Kyong Chun describes public perceptions of the women who programmed the Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer during the Second World War, known as the ‘ENIAC girls’. She writes:

The move to reclaim the ENIAC women as the first programmers in the mid- to late-1990s occurred when their work as operators … had become entirely incorporated into the machine and when women ‘coders’ were almost definitively pushed out of the workplace. (Chun Reference Chun2011: 35)

She continues, in a phrase that brings to mind the nostalgic and romanticised aspects of some of the narratives around women in electronic music, ‘It is love at last sight’ (ibid.). Chun is using the word ‘sight’ colloquially here, but visual documentation of the women working on ENIAC would have been a key part of the reclamation she describes, as there were many photographs of them taken at the time, photographers evidently enjoying the novelty of the pairing of feminine young women and monolithic machine, as well as wanting to present an image of women’s patriotism and public service during wartime (Figure 3). These photographs of women operating vast computers, using an interface which consists of, as Chun puts it, ‘transparent holes’ (ibid.), recall the visual documentation of early electronic music, especially modular synthesis; therefore Chun’s notion that these women are celebrated at the moment at which they will become disempowered makes these images all the more compelling. She writes:

Reclaiming these women as the first programmers and as feminist figures glosses over the hierarchies within programming – among operators, coders and analysts – that defined the emergence of programming as a profession and as an academic discipline. (Chun Reference Chun2011: 37)

Figure 3 The programmers of ENIAC. US Army photo.

The concentration of images of female pioneers of electronic music in the 1960s and 1970s effects a similar glossing over – not only of the challenges, isolation and discrimination faced by the women in those images, but also over the inequalities in the field of music technology, pedagogy and performance that continue in the present day. Considered from this viewpoint, the archival image of the woman with the machine comes freighted with a history of inequality and undervalued labour that makes it hard to unequivocally enjoy. We might wonder, then, why it is such a source of visual pleasure as to be repeated so often, and ask therefore who its intended viewer might be. Laura Mulvey’s notion of how fetishisation of certain aspects of a woman’s appearance serves to make safe for the male viewer the female subject in cinema (Mulvey Reference Mulvey1975) comes to mind when looking at, for example, images of Eliane Radigue at her ARP system and Delia Derbyshire operating tape reels (Figures 4 and 5). In its circulation via the multiple repetitions of the internet, the archival photograph of a woman posed with analogue or early digital music technology has become a fetish object in itself and subsequently ironised, as I will describe below.

Figure 4 Eliane Radigue, mid-1970s. Photo by Yves Armand.

Figure 5 Delia Derbyshire, 1965. © BBC Photo Library (licence granted in September 2016 for use in August 2017 issue of Organised Sound).

6. FINDING URSULA BOGNER

The notion that the woman in electronic music history is not only a genre but also a visual trope can be seen in the phenomenon of Ursula Bogner. In 2009 the German electronic musician Jan Jelinek started to release records by Ursula Bogner, a now dead electronic musician whose 1950s and 1960s archives he claimed to have discovered via a chance meeting with her son. Jelinek built an elaborate mythos around Bogner, which included photographs – of whom, it has not been revealed, but it is certainly not Bogner, who never existed. Jelinek’s project was an ironic comment on the attraction of the underground electronic music collector to the female pioneer trope, the implication being that had he released the same music under his own name it would have met with less attention.

It should be noted that Jelinek is cisgendered and his adoption of a feminine persona is, as far as I am aware, confined to this project; my misgivings about it are therefore not criticisms of fluid gender roles – in fact I would argue that his project actually trivialises the histories of transgender and non-binary identified people in electronic music and sound. I am also not seeking to decry performance and artifice in electronic music, nor the practice of inventing histories and fictional personae, which is a well-established artistic strategy. For example, in 2014 the composer Jennifer Walshe founded Aisteach, a project described as ‘the avant-garde archives of Ireland’.Footnote 9 Aisteach proposed an imaginary history of an Irish avant-garde, producing a website and book, as well as compositions by such made-up figures as Eyelen Mullen-White and Sister Anselme O’Ceallaigh (two of the composers from the ‘Women’ section of the Aisteach website – the Irish avant-garde also has its female pioneers). Where Aisteach and Ursula Bogner differ, though, is in the position of the projects’ creators to their subject. As an Irish woman composer concerned with experimental, interdisciplinary practice, Walshe’s project makes the point that she does not in fact have antecedents, or a history of pioneers to celebrate, not just because of her gender but because of her identity as a person from a formerly colonised country. In contrast, Jelinek has plenty of forebears and peers. When read as comment upon the fetishisation of the image of the woman with a machine, the Bogner project has some value, but it is also reflective of a highly gendered electronic music culture in which the ‘historical woman’ is unthinkingly objectified for a presumed majority male, heterosexual audience. When one sees a live performance of Bogner/Jelinek’s music, in which Jelinek and his male collaborators play and manipulate tapes while images of an unknown woman (playing the role of Bogner) are projected above them, it is clear that Jelinek is deeply embedded in that culture (Figure 6).

Figure 6 A performance of the music of Ursula Bogner at Soco Festival, Uruguay, 2013. Photo by Martin Craciun, Soco Festival.

7. CONCLUSION

In his writing on the ethnomusicological past, Philip Bohlman describes how we come to perceive past as ‘other’, by constructing it in a way that emphasises its distance from the present. This means that it is harder to understand in terms of sameness and difference, but remains static, easy to make exotic and museum-worthy. Instead, he advises, there is a ‘need to start to perceive how music brings competing identities into the tension of history’ (Bohlman Reference Bohlman2008: 258).

Many new media representations of women in electronic music history perform the process of ‘othering’ that Bohlman describes, despite the existence and potential of numerous other approaches to histories of music, technology and gender, some of which I have touched upon in this article. I conclude by suggesting that the deeply embedded political and economic structures of these media encourage a particular method of writing and making visible/audible histories of music and sound, and that these conditions are dissonant with a feminist approach to electronic music histories.

However, I propose that there is great potential in exploring, as Tara McPherson suggests (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2015), the ways in which identities such as gender are not only represented but encoded in the digital media through which feminist histories of electronic music are increasingly transmitted. This is an aim that should extend to an exploration of the design and interfaces of music technology itself, so that the gender of the person using the machine is of less importance than the more subtle, shifting and contentious discussion of how gender is articulated by and through the machine itself.