1. Introduction

Until recent decades, little systematic attention has been paid to the diverse nature of Karelian names of domestic animals, but the names of cows and their connection with Karelian anthroponyms have now come under scrutiny. The contacts between Karelian and Russian names of cows have also been discussed (see e.g. Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2018b, Reference Kuzmin2022). However, as yet there has been no comprehensive study of the Russian-origin cow names given by Karelians. It is also unknown whether there are spatial or temporal variations in the occurrence of Russian-origin cow names. This article aims to fill this gap and serves as a starting point for further studies devoted to the Karelian names of domestic animals. As a whole, Karelian animal names represent a fruitful topic for research: they can be approached in terms of their meaning, structure, and linguistic background, since speakers of Karelian have lived for centuries in multilingual areas where linguistic influences have also affected the name system.

The intention of this article is to analyse the cow names used by Karelians, especially those names that are of Russian origin. As will be shown in Section 5, the research data were collected by means of interviews in the 2010s and are of Russian origin. The interview data are compared with a smaller and older data set extracted from the Dictionary of Karelian (Finn. Karjalan kielen sanakirja, henceforth referred to as KKS). The dictionary contains both Karelian and Russian-origin onomasticon, but for the purposes of this study and for ease of comparison, I compare the interview data only with the Russian-origin material in the dictionary.

The Russian language and its predecessors have influenced the Karelian language and its predecessors for centuries, and the aim of the present study is to discover how the contacts between the speakers of Karelian and Russian are visible in the onomasticon of cows. Thus, the study aims at contributing to the studies of Karelian–Russian contacts and also to the studies of cattle names.

The article will focus on proper names, but also on the various denominations, i.e. the expressions used to describe, for example, a cow of a certain colour. Hence, the focus of this article is on the borderline between onomastics and lexicography: the study of proper names belongs to the field of onomastics, whereas the appellatives that often underlie cow names and denominations require a lexicographical approach.

The main purpose of this article is to discuss the nature of the Russian-origin cow names given by speakers of Karelian. The aim is to examine the meaning of the Russian-origin names, i.e. the principles underlying the Russian names given, and to determine the most common principles. In the case of Russian names, it will also be determined whether they have Karelian equivalents or whether, for example, a particular colour of a cow is described only by a Russian name or denomination. In addition, an attempt will be made to determine whether there is spatial or temporal variation in the occurrence of Russian-origin cow names.

Finally, this article is organised as follows: first, I present the Karelian language (Section 2) and provide general information about previous research on Finnic cow names and potential data sources (Section 3). Section 4 provides an overview of the Russian-origin onomasticon in the eastern Finnic languages and of the use of anthroponyms as cow names. The data and method of the study are described in Section 5, while Sections 6 and 7 comprise the analysis per se, proceeding from older data to more recent. Finally, Section 8 will summarise the findings.

2. The Karelian language

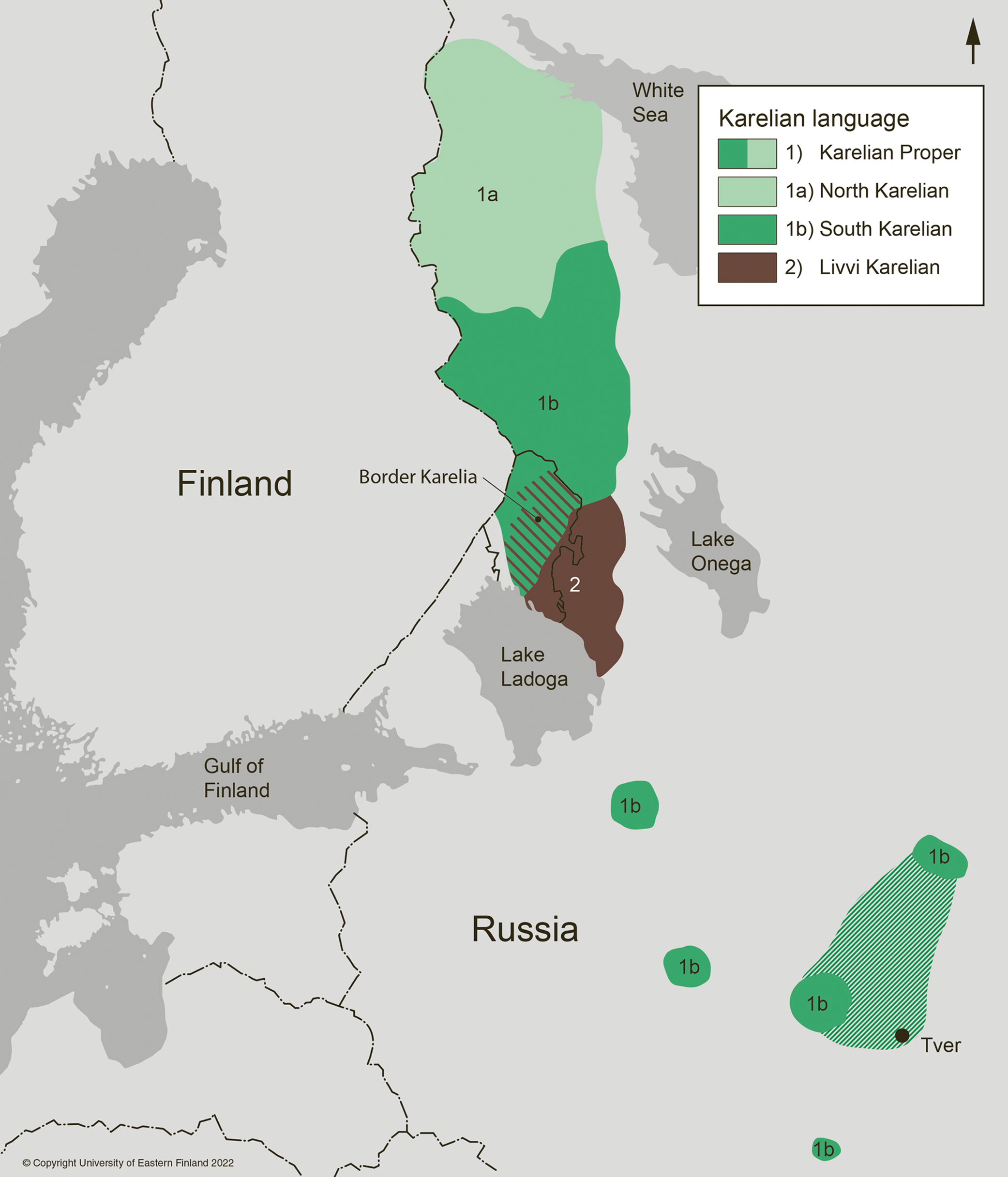

Karelian is a member of the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages. According to the currently most frequently held understanding, Karelian can be divided into two main dialects: Karelian Proper and Livvi-Karelian. Karelian Proper can be further subdivided into Viena Karelian (also referred to as North Karelian, White Sea Karelian) and South Karelian (see e.g. KKS, Sarhimaa Reference Sarhimaa2017:29). Traditionally, Karelian has been spoken in northwestern Russia and in eastern Finland (see Figure 1). Karelian-speaking areas have been characterised by multilingualism throughout history. Karelian speakers have lived in the vicinity of other Finnic languages and Slavic languages for centuries and hence bilingualism, or at least some command of neighbouring languages, has been commonplace among Karelians.

Figure 1. Speaking area of the Karelian language.

In present times, the main speech area of Karelian is the Republic of Karelia in Russia: Viena Karelian is spoken in the northern part of the Republic of Karelia (also referred to as Viena Karelia, North Karelia, White Sea Karelia), South Karelian to the south of the Viena region, and Livvi-Karelian in the southern part of the Republic of Karelia on the isthmus between Lakes Onega and Ladoga. In the research tradition concerning the Karelian language, the speaking area of Livvi-Karelian is referred to as Olonets Karelia. In Inner Russia, Karelian has been spoken in the Tver, Tikhvin, and Valday regions since the seventeenth century, and in Tver up to the present day. The Karelian settlements in the Tver region originate mostly from the South Karelian area, and the Karelian spoken today in Tver is considered a sub-dialect of South Karelian. There is no reliable information about the number of speakers of Karelian in Russia, but it is likely that there are at least 20,000–30,000 speakers (Karjalainen, Puura, Grünthal & Kovaleva Reference Karjalainen, Puura, Grünthal and Kovaleva2013). The language is considered to be endangered both in the Republic of Karelia and in the Tver region, and all of its speakers are bilingual, with Russian as their other native language.

In Finland, Karelian was spoken mainly in the region of Border Karelia until the Second World War. Border Karelia was essentially a South Karelian area, but Livvi-Karelian was also spoken in some of its regions. The area formed a dialect continuum: the eastern dialects of Finnish were spoken in the westernmost parts of Border Karelia, while the neighbouring dialects in the east represented South Karelian. Further to the east, more elements of Livvi-Karelian mixed with South Karelian, until the dialect was broadly Livvi-Karelian in the easternmost parts of the region. After the Second World War, Border Karelians dispersed to various parts of Finland. The other significant group of Karelian speakers in Finland were Karelians who migrated from Russia in the 1920s following the October revolution. There have also been speakers of Viena Karelian in three border villages in the Kainuu region. There are no exact statistics on the speakers of Karelian in present-day Finland, but it is assumed that there are about 11,000 people who speak the language at least fairly well and up to 20,000 who understand it (see Koivisto Reference Koivisto2017:424–425 and the references therein).

3. Research on Finnic cow names

Onomastic research distinguishes between proper nouns and appellatives. Proper nouns are the names of people, animals, places, and companies, while appellatives are words describing creatures, objects, and places and their characteristics (Ainiala, Saarelma & Sjöblom Reference Ainiala, Saarelma and Sjöblom2012:13). A proper noun identifies its target, whereas an appellative describes and categorises a specific target. When studying the onomasticon of domestic animals, the boundary between the proper names and denominations (i.e. appellatives describing the physical appearance or character traits of animals) is often blurred. For example, an adjective describing a colour can serve both as a proper name of a cow and as a denomination for cows of a certain colour (see e.g. Koski Reference Koski1983:53–54; Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2005:57–59, Reference Reichmayr2015:371).

Names and denominations are usually based on a principle of naming, such as the colour of a dog or the name of a town’s founder. Thus, the name often has a meaning: it has not been insignificant whether a black dog has been called Musti (< Finn. musta ‘black’) or Harmi (< Finn. harmaa ‘grey’).Footnote 1 However, according to Ainiala et al. (Reference Ainiala, Saarelma and Sjöblom2012:31–32), the identifying function of a name remains even if the user of the name does not know what the name means. In discussions of the meaning of a name, attention is often focused on the lexical meaning. It is true that at the time of giving a name, for example a place name, the purpose is often to describe its target in some way. When we examine this ultimate meaning of a name, i.e. the principle of naming, we are examining its etymological meaning. In the present article, the focus is placed precisely on the etymological meanings of cow names and their relation to their meaning, i.e. denotation.

Cows have been given names probably as long as they have lived alongside human beings. The oldest known cattle names (cow and ox names) are more than 2,000 years old and date back to ancient Greek and Indian sources (Leibring Reference Leibring2002:81, Reference Leibring2020:102, Reference Leibring2021:248; Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2005:73). Naming other domestic animals has also been commonplace, although the need to name an individual has varied from species to species. It has not been customary to name all individuals of a domesticated species: an animal is named if it is perceived or treated as an individual, if it is expected to live for many years, if there is a need to distinguish it from other individuals of the same species, or if it is clearly distinguishable from others, for example by its appearance (Ainiala et al. Reference Ainiala, Saarelma and Sjöblom2012:204, Leibring Reference Leibring and Hough2016:3).

Principles of naming domestic animals vary, but there seem to be certain universal tendencies when it comes to naming, for example, a cow. According to research on European cow names, the most common and most traditional principles of naming a cow are colour, physical appearance, time of birth, character traits, and place of origin. Using anthroponyms as cow names and giving cows names based on human or mythological characters have also occurred, especially in modern times (see e.g. Leibring Reference Leibring2000:349–350, 353–363, Reference Leibring2002:83–86, Reference Leibring2021:249; Faster & Saar Reference Faster and Saar2021:19–22; Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2005:133–134, Reference Reichmayr2015:371).

Cow names appear in diverse materials that have usually been collected for purposes other than studying the nature of cow names, such as old estate inventories (see e.g. Leibring Reference Leibring2002:81, Reference Leibring2020:103; Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2005:73–76, Reference Reichmayr2015:372–376). In Finland, cow names have been recorded in various documents since at least the seventeenth century, albeit in a sometimes haphazard and shaky orthography. Apart from estate inventories, cow names can be found in the Finnish–Swedish dictionaries of Juslenius (1745), Ganander (1786–1787), Renvall (Reference Renvall1823–1826), Helenius (Reference Helenius1838), and Lönnrot (1880, A. H. Kallio’s supplement 1886) (see Koskimies Reference Koskimies1913). Finnish dialect dictionaries (e.g. R. E. Nirvi Reference Nirvi1974–1981) also contain a large number of cow names (Vatanen Reference Vatanen1997:17, 21, Kaarlenkaski & Saarinen Reference Kaarlenkaski and Saarinen2013:151). Cow names and denominations collected in different parts of Finland, the ceded Karelia, and Ingria have also been entered in the Dictionary of Finnish Dialects (Finn. Suomen murteiden sanakirja, henceforth referred to as SMS). In addition, Finnish–Karelian cow names appear in works based on folk poetry, such as Kalevala, Kanteletar, and Suomen kansan vanhat runot (‘The ancient songs of the Finnish people’), whose material provides indications of the old ways of naming cows in the Finnish–Karelian region and, more widely, in the eastern Finnic cultural area.

In addition to the above-mentioned sources, Finnic cow names can also be found in the dictionaries of the dialects of Estonian (Eesti murrete sõnaraamat, EMS), the Salmi dialect of Karelian (Pohjanvalo Reference Pohjanvalo1950), the Ludic dialects (Lyydiläismurteiden sanakirja, LMS), the Vepsian language (Slovar’ vepsskogo jazyka, SVJA), the Kukkozi dialect of Votic (Vatjan kielen Kukkosin murteen sanakirja, VKKMS), the Jõgõperä dialect of Votic (Vatjan kielen Joenperän murteen sanasto, VKJMS), and the Ingrian dialects (Nirvi Reference Nirvi1971). The name material in these dictionaries will be compared with the data used in this article; in particular, the material recorded in the Ludic areas provides an interesting point of comparison and contributes to the understanding of connections between Karelian and Ludic, which are especially diverse between the South Karelian dialects and Ludic (Pahomov Reference Pahomov2017:212–251, 264–270).

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Finnish cow names were studied by Aspelin (Reference Aspelin1886) and also Könönen (Reference Könönen1915), whose data were collected in Ladoga Karelia, and Lukkarinen (Reference Lukkarinen1939), who studied the cattle names drawing on dictionary data.Footnote 2 Ojansuu (Reference Ojansuu1912, Reference Ojansuu1916) compared Finnish, Estonian, and a few Karelian and Vepsian cattle names, as well as horse and dog names, with the aim of forming an idea of the principles of animal naming in the ‘early Finnish period’. The Karelian cow names in Ojansuu’s data refer to the day of the week of birth (e.g. Endzikki < enzimänargi ‘Monday’, Pyhikki < pyhäpäivä, -y ‘Sunday’). According to Ojansuu (Reference Ojansuu1912:17, 26), there are equivalent derivative suffixes for different animal species in Finnish and Estonian: Finn. Mustikki ∼ Est. Mustik (cow), Finn. Musta ∼ Est. Must, gen. Musta (horse), and Finn. Musti ∼ Est. Must, gen. Musti (dog). Thus, the traditional Finnish, Estonian, and, at least for cows, Karelian names seem to have a common background. Following Ojansuu, Estonian cow names were studied by Palmeos (Reference Palmeos1955), but no extensive research was conducted on them until recent times (Faster & Saar Reference Faster and Saar2016, Reference Faster and Saar2021).

Despite the name collections of the KKS and a few individual researchers, cow names used in the Karelian-speaking regions have not been studied until recently (Karlova Reference Karlova2015, and personal communication). The research gap has been filled by Denis Kuzmin, and he has attempted, amongst other topics, to prove that traditional Karelian cow names are descended from pre-Christian anthroponyms (Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin, Ainiala and Saarikivi2017a, Reference Kuzmin2018a, Reference Kuzmin2021, Reference Kuzmin2022).

4. Russian origin in the onomasticon of the Finnic languages

The common ancestral language of modern Russian and other Slavic languages was Proto-Slavic, which began to diverge in 500–100 CE (Lindstedt Reference Lindstedt2020:11, 56). In loanword research, it has been customary to speak of both Slavic and Russian influences on the Finnic languages, even when referring to loans adopted at the same time. The oldest Slavic loanwords are generally considered to be those borrowed from the predecessors of modern Russian, i.e. pre-Russian and ancient Russian (Jarva Reference Jarva2003:35, 37–38 and the references therein). For more than 100 years, Slavic loanwords in Finnic languages have been classified into older words, i.e. those inherited from pre-Russian at the earliest, and younger words borrowed from modern Russian (e.g. Mikkola Reference Mikkola1894, Kalima Reference Kalima1952). In recent decades, research on Russian loanwords has expanded to include dialects of the Finnic languages (e.g. Must Reference Must2000, Jarva Reference Jarva2003, Björklöf Reference Björklöf2018), highlighting the fact that the amount of Slavic vocabulary is considerable at the dialect level, including languages other than Karelian and Vepsian (Saarikivi Reference Saarikivi2009:120).

Slavic influence is discernible in the onomasticon throughout the Finnic-speaking area, in both toponyms and anthroponyms. The influence is most noticeable in the areas that have been under the influence of the Eastern Orthodox Church, such as the Karelian-speaking areas (e.g. Nissilä Reference Nissilä1975:188–210). It is also visible, especially in family names, in the regions of Karelia and Savo in modern Finland (Nissilä Reference Nissilä1975:204–210, Reference Nissilä1976:143), including Border Karelia, whose population were largely Karelian-speaking and Orthodox (Patronen Reference Patronen2017:172–173). The Russian influence on Karelian anthroponyms has been studied, in particular, by Kuzmin (e.g. Reference Koivisto2017a, Reference Kuzmin2018b) and Karlova (e.g. Reference Karlova2007, Reference Karlova2016).

Names have been borrowed from Russian and its predecessors especially by the eastern Finnic languages. The speakers of Karelian were influenced in early times by the Orthodox Church, and the anthroponyms they used underwent a major change with the advent of Christianity (Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2018b:97–98, Reference Kuzmin2022:248–252). Christian names developed into hypocorisms, which became established over the centuries. In the Karelian-speaking regions, however, vernacular hypocorisms did not become official names in the same way as in Lutheran Finland. Thus, Karelians in Russia have official first names like many other ethnic minorities in Russia, and their Karelian hypocorisms have been and sometimes continue to be used in informal situations (e.g. Kar. Outi < Russ. Yevdokiya, Kar. Muarie < Russ. Mariya).Footnote 3

Vernacular hypocorisms have apparently not been used in the past as zoonyms. Instead, it has been speculated that, with the advent of Christianity, old pre-Christian names shifted to become animal names, e.g. Lemmikki, Lokka. It is also likely that many Russian cow names can be traced back to pre-Christian Russian female names, as there are considerable similarities in the names (e.g. Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2018b, Reference Kuzmin2021). The ancestors of modern Karelians and Russians lived in the vicinity of each other, drawing influences from each other. According to Kuzmin (Reference Kuzmin2018b:100–102), it is therefore possible that, for example, Karelian cow names such as Muštikki ‘black cow’ and Pienikki ‘small cow’ are originally linked to pre-Christian Russian female names: the Russian female names Chërnava < Russ. chërnyy ‘black’ and Malyuta < Russ. malen’kiy ‘small’ would have become cow names, and their Karelian counterparts Muštikki and Pienikki would have undergone a similar development.

Nowadays, on the other hand, it would appear from the interviews I conducted that the affectionate and colloquial forms of Russian names are widely used as zoonyms (e.g. Maša < Mariya, Vanja < Ivan), although they are not used as official anthroponyms. Using colloquial forms of female names (as well as female names in general) as cow names has also become common in many other European countries (see e.g. Leibring Reference Leibring2002:86–88, Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2015:79–84, Faster & Saar Reference Faster and Saar2021:21). In the past, cows and oxen were also given anthroponyms that were known but not used among the local people, for example exotic and upper-class names (see e.g. Leibring Reference Leibring2002:86). Both the new and the older practices reflect the position that anthroponyms and zoonyms are not fully comparable: animals are given names that for one reason or another do not fit as official anthroponyms (see also Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2015:378).

5. Data and methods

I collected my research data by means of interviews conducted during three field trips in Olonets Karelia and Tver in 2012–2018. The interview data include 53 cow names. I will compare the interview data with the data recorded in the Karelian–Finnish Dictionary of Karelian (KKS). The KKS data comprise 12 names and 10 denominations of cows. It is obvious that such a relatively small data set represents only partially the older Russian-origin onomasticon. The KKS data are nevertheless sufficient to provide reliable information on the ways in which cows have been named in the Karelian-speaking regions in the past.

The KKS was compiled in the Karelian-speaking region by several collectors between the years 1871 and 1966. The dictionary contains cow names and other zoonyms from all of the Karelian-speaking areas, i.e. the Viena, South, and Livvi-Karelian areas of the present-day Republic of Karelia, as well as Border Karelia and the Karelian language islands of Inner Russia, i.e. the regions of Tver, Tikhvin, and Valday. However, the dictionary clearly focuses on Olonets Karelia and Border Karelia, as can be deduced from the name data. Border Karelia was a border region where South and Livvi-Karelian and also eastern dialects of Finnish were spoken. In the following analysis, I will distinguish between the names recorded in Border Karelia and those recorded in the Viena, South, and Livvi-Karelian regions.

The initiative of the KKS was to present not the Karelian onomasticon but the vocabulary of Karelian, and the proper names of animals were included in the dictionary as an additional resource. It is unclear how systemically zoonyms were collected and hence a number of zoonyms may have been unintentionally excluded. Anthroponyms are not included in the dictionary at all. At the time of collection of the material for the KKS, most Karelian-speaking people already had a Russian-origin first and last name. Karelian names and vernacular hypocorisms of Russian origin were used as well, but none of these names have been included in the KKS. Anthroponyms and zoonyms were treated in a different way: zoonyms were apparently perceived as part of the vocabulary of Karelian, whereas anthroponyms were not. The KKS includes both proper names and denominations of animals. In the word entries contained in the dictionary the proper names are indicated with explanations such as lehmän nimenä ‘as a cow’s name’. In the case of denominations, explanations such as tummanruskeasta lehmästä ‘of a dark brown cow’ are used.

My interview data were obtained from Karelian speakers of middle age and above using thematic interviews. In addition to cow names, I also collected other zoonyms. The interviews were conducted in Karelian, although some Russian and Finnish was also used.Footnote 4 Especially in Tver, most of the interviewees knew about the Karelian-language interview in advance, and therefore speaking Karelian was not unexpected and they were able to prepare themselves for it. In Olonets Karelia, part of the field work was conducted using a door-to-door method, which resulted in various forms of Karelian-language encounters.

The command of Karelian varies from speaker to speaker: Karelian is not the language of everyday communication for most of the people in Tver and Olonets Karelia, and the language is endangered in both regions. Russian is nowadays the strongest language for most of the speakers of Karelian, and some of the informants tended to switch to Russian during the interviews. Tver Karelians do not usually know Finnish. For historical and geopolitical reasons, in Olonets Karelia it is relatively common, especially for the older generation, to know at least some Finnish. Some of the Olonets Karelians used some Finnish during the interviews, and it was also common for them to attempt to use Russian.

In the course of the field work I started most of the interviews by asking the interviewees about their own current or previous domestic animals or pets. In addition, I asked them what kind of zoonyms they were familiar with. The age of the names was of particular interest. Unless the interviewee raised the topic on their own initiative, I always asked them to specify whether the names were similar in the interviewee’s childhood and whether the interviewee felt that the names had undergone change. A significant proportion of the data represent cow names used in the interviewees’ youth or during their working life, as few people today have cows of their own and hence they could provide little information about their names. Thus, the interview data represent much younger names than the KKS data. Another difference from the KKS data is that the interview data consist almost exclusively of proper names of cows rather than denominations (appellatives describing, for example, cows of a certain colour). Thus, these two sets of data are not directly comparable. However, an examination of the interview data in the context of the KKS reveals certain tendencies in the naming practices of Karelian speakers.

The interview data exclude names based on a Russian variant of Christian or other modern anthroponyms. Such cow names are commonplace in contemporary Karelia, and I recorded 6 of them in Tver and 8 of them in Olonets Karelia (e.g. Katka < Yekaterina, Maša < Mariya, Nad’a < Nadezhda; see also Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2018b). As discussed above, there are no such names in the KKS, and for ease of comparison I have omitted such names from the interview data. The absence of such names in the KKS does not necessarily indicate that Karelians did not use such cow names at the time of completion of the KKS. Rather, it is possible that such names were used but they were not entered in the dictionary. Russian-origin anthroponyms may have represented names that were too Russian to be included in a dictionary that aimed at presenting the Karelian language. Names such as Maša and Katka may also have been treated differently from names such as Pesroi and Buura simply because they do not represent the vocabulary of Karelian. Buura is also an adjective meaning ‘dark brown’, whereas Maša is ‘just’ a female name. It is likely that this kind of difference has played a role, even though proper names and denominations of cows are clearly separated in the word entries in the KKS.

The interview data and the KKS data differ essentially from each other in both quantitative and qualitative terms, which must be borne in mind when drawing conclusions. The KKS data serve as a historical background for the research and help in the interpretation of the interview data and the findings that emerge from it. At this point I will then turn to the Russian-origin cow names recorded in the KKS (Section 6), which will be followed by the cow names represented in the interview data (Section 7).

6. Russian-origin cow names and denominations in the Dictionary of Karelian

6.1 Russian-origin cow names

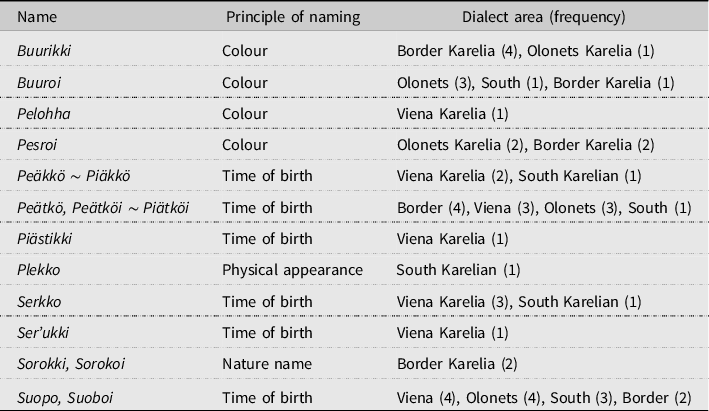

The Dictionary of Karelian (KKS) contains 12 Russian-origin cow names that have been unambiguously classified as proper names; the rest of the data consist of denominations (see Section 6.2). The Russian-origin cow names in the KKS have been given according to the time of birth, colour and other types of physical appearance, and they also include so-called ‘nature names’ (for the term, see e.g. Ainiala et al. Reference Ainiala, Saarelma and Sjöblom2012:135). The complete name data are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Russian-origin cow names in the Dictionary of Karelian (KKS)

There are four Russian-origin cow names describing colour in the KKS: Pelohha < Russ. beloi ‘white’, Pesroi < Russ. pëstroi ‘variegated’, and Buurikki and Buuroi < Russ. buroi ‘dark brown’.Footnote 5 Pelohha is recorded only in Viena Karelia. The name is a direct loan from the Russian cow name Beloha, although the plosive b is voiceless in Viena Karelian.Footnote 6 -ha is a derivative suffix describing the large size of an animal and it is typical of Russian cow names (verbal communication from an informant in the Tver region). In Viena Karelia the Russian loanword for the adjective ‘white’ was apparently not used in the past as it was in Border Karelia and Tver (KKS s.v. pieloi), nor was the Karelian adjective valkie ‘white’ used to form names for cows or other domestic animals, with the exception of the reindeer name Valakko (KKS s.v. valkko and valkoi). Instead, the name or denomination for a white cow has been Joučikki ∼ Joučikko ∼ Joučikoi < Kar. joučen ‘swan’ in Viena Karelia and widely elsewhere in Karelia;Footnote 7 in Viena also Lokka ‘seagull’.Footnote 8 In Ludic a white cow was called Bieloi (LMS s.v. bieloi), and in Vepsian, beloi or beloo (Vepsian denomination being vaugoo, see SVJA s.v. beloi, vaugoo).

The name Pesroi is a direct loan from the North Russian adjective pëstroi < Standard Russian pëstryy ‘variegated’ (Kalima Reference Kalima1952:25, 79). The adaptation to the Karelian phonetic system is indicated by the lightening of the consonant cluster. The Finnic counterpart of the name, Kirjo(i), has been recorded in all of the Karelian-speaking areas apart from the language islands. However, according to the KKS, Border Karelia is the only area where both the Russian-origin and the Finnic variant have appeared as proper names.Footnote 9

The name Buurikki is based on the noun and adjective buur|a, -u, which is formed from the Russian feminine adjective buraya ‘dark brown’ (KKS s.v. puura). According to Kalima (Reference Kalima1952:53–54), the long u in Russian has been replaced in the oldest loanwords by the diphthong uo in both Karelian and Finnish (e.g. kuoma < Russ. kum ‘friend’, ‘companion’), while in later loanwords, especially the stressed u is replaced by a long u, as in the noun buura. The name Buurikki has been recorded mostly in the eastern parts of Border Karelia but also in Olonets Karelia. The name differs in its Karelianness from the two discussed above: -kki is the most common cow name derivative suffix in the names recorded in the Viena, South, and Border Karelian dialects, and in Olonets Karelia it is the second most common after the suffix -Oi (Massinen Reference Massinen2017).

The name Buuroi, derived directly from the masculine adjective form buroi, is recorded in the South Karelian dialect area, Border Karelia, and in a wide area in Olonets Karelia; the name has also been used in the Ludic area (LMS s.v. buuroi). The name is similar in form to the -Oi-derived nouns typical of Livvi-Karelian (Bubrih, Belyakov & Punžina Reference Bubrih, Belyakov and Punžina1997:41). The distributions of these two names show that the -kki-derived variant has been more widely used in Border Karelia, while the -Oi-derived one has been used especially in Olonets Karelia; in the actual South Karelian dialect area there are no other -Oi-derived cow names, and the derivation is not typical of the dialect area (Bubrih et al. Reference Bubrih, Belyakov and Punžina1997). The noun buur|a, -u and its derivatives have also been used as appellatives for ‘a dark brown cow’, to which I will return when I discuss the denominations.

-kki with its variants is a common Finnic cow name derivative suffix (Vatanen Reference Vatanen1997), while the -Oi-derived cow names are characteristic of the Olonets and Border Karelian regions (Massinen Reference Massinen2017). This indicates a more extensive Russification of Livvi-Karelian in relation to Viena and South Karelian. -Oi is also an old Finnic noun derivative suffix, which is commonly found, among the Karelian dialects, only in Livvi-Karelian (Ojansuu Reference Ojansuu1918:137–139, Bubrih et al. Reference Bubrih, Belyakov and Punžina1997:41; see also Rapola Reference Rapola1919–1920:37–72, Reference Rapola1966:470–472). However, in the Russian-origin vocabulary of Livvi-Karelian, it is a direct loan from Northern Russian dialects. The suffix is often equivalent to -O in Viena and South Karelian, both in the Finnic and Russian vocabulary (e.g. Kirjo ∼ Kirjoi, cf. the anthroponym Natto ∼ Natoi < Russ. Natalya).

Both the KKS and the Dialect Atlas of Karelian (Finn. Karjalan kielen murrekartasto, Bubrih et al. Reference Bubrih, Belyakov and Punžina1997) show that the suffix -Oi also occurs locally in South Karelian dialects; according to Ojansuu (Reference Ojansuu1918:137), the suffix also occurs in the Livvi-Karelian form in the eastern Border Karelian dialects. -Oi is also common amongst cow names in the Border Karelian dialects: it is the second most common derivative suffix after the suffix -kki (Massinen Reference Massinen2017). It should be noted, however, that the regional variation -Oi ∼ -O does not occur when -Oi is a part of a direct North Russian adjective loan (Buuroi, Pesroi but not *Buuro, *Pesro).

As shown above, a slightly more common principle of naming has been the time of birth, i.e. the day of the week on which the cow was born. Names of Russian origin based on the time of birth occur in all dialects of Karelian. The Karelian names for Monday, Tuesday, and Sunday (in South and Livvi-Karelian also for Wednesday) are original, and there are plenty of cow names based on them in all dialects, e.g. Enčikki ∼ Endžu < enzimänargi ‘Monday’, Toinikki ∼ Toissi < toinargi ‘Tuesday’, Pyhikki ∼ Pyhöi < pyhäpäiv|ä, -y ‘Sunday’. The Karelian names for the days of the week may have been used as a model for the formation of names on the basis of Russian loans, although it is not certain whether Karelian names for the days of the week were used before the introduction of the Russian names, or whether the original names of the days of the week are translation loans. Similar cow names based on the day of the week also occur at least in Finnish (SMS e.g. s.v. ensikki, kestikki, laukeri), Estonian (Esik, Tesik etc.; EMS s.v. esik; Faster & Saar Reference Faster and Saar2016, Reference Faster and Saar2021:19), and Ludic (LMS s.v. endzoi, pyhöi etc.).Footnote 10

As for the Russian-origin names for the days of the week, the word serota < Russ. sreda ‘Wednesday’ (KKS s.v. serota) was borrowed by the predecessors of the present-day Viena Karelian, the transitional dialects between Viena and South Karelian and the dialects of the Karelian language islands. Names have also been formed on the basis of this loanword. A name with the suffix -kki, Ser’ukki ‘a cow born on Wednesday’, has been recorded in the area of the transitional dialects. Elsewhere in Viena Karelia, a name with the suffix -kko, Serkko, has been used, as well as in the area of the transitional dialects. According to the KKS, the name Serkko has been used precisely for a cow born on Wednesday. However, it is worth noting that the appellative serkko has also been used in the area of transitional dialects for light grey or white horses, with the underlying Russian serko < seryy ‘grey’ (see Koski Reference Koski1983:207).

All dialects of Karelian have Russian-origin words for ‘Friday’ (Russ. pyatnitsa > Kar. piätničč|ä, -y etc.) and ‘Saturday’ (Russ. subbota > Kar. suovatt|a, -u) (e.g. Kalima Reference Kalima1952:58, 166). The name variants Peätkö (Viena, South Karelia) and Peätköi ∼ Piätköi (Border, Olonets Karelia) ‘born on Friday’ and Šuopo (Viena), Suobo ∼ Šuobo (South Karelia) and Suoboi (Border, Olonets Karelia) ‘born on Saturday’ have a particularly wide distribution; these names have also been used in the Ludic (LMS s.v. piätköi, suoboi) and Vepsian (SVJA s.v. soboi) areas. In addition, the names based on the time of birth show the regional derivative suffix -O ∼ -Oi variation mentioned above. Although the Border and Livvi-Karelian (as well as Ludic and Vepsian) Peätköi and Suoboi etc. are of Russian origin, the derivation -(k)Oi is of Finnic origin and not part of a North Russian adjective as in Buuroi and Pesroi above. Cows born on a Friday have also been called Peästikki in Viena Karelia, and Peäkkö ∼ Piäkkö in both the South and the Viena Karelian area.

It is noteworthy that the names meaning ‘born on Saturday’ do not in fact seem to be based on the adapted noun suovatt|a, -u, but the name derivations show the loan original plosive b (∼ p): suobo, etc. < subbota. This indicates the interpretation that the derivatives were formed before the development of the variant with a v. In Ludic, variation occurs between the voiced plosive and the approximant: suobat ∼ suovat, in Vepsian sobat is exclusive (Kalima Reference Kalima1952:66; the variant with an approximant is also found in Skolt Sámi: suuvv´ed´).Footnote 11 Equally, the diphthong uo in cow names reveals that they are Karelian and not direct loans from Russian, since the word-initial diphthongisation (here u > uo) is typical of the older stratum Slavic loans of Karelian. In more recent loanwords, the Russian u has been replaced by a long or short u rather than a diphthong (Kalima Reference Kalima1952:53–54).Footnote 12

In the eastern parts of Border Karelia, ‘a white-headed cow’ has been referred to by a nature name, Sorokoi or Sorokki (also Pohjanvalo Reference Pohjanvalo1950); in Olonets Karelia, only Sorokoi has been used. The name is based on the Russian soroka ‘magpie’, which is also the origin of the nouns sorokka and harakka, which occur in the eastern dialects of Finnish for the Karelian folk costume hat (KKS s.v. sorokka, SMS s.v. harakka III.1, and harakkamyssy). The name Sorokoi ∼ Sorokki for a white-headed cow may refer to a head that is distinguishable from the rest of the body as a form of headgear; the connection with the all-black head of a magpie is less likely.Footnote 13 The Karelian equivalent of the names is Valgiepeä ‘white head’, recorded in the South Karelian region, which does not occur in other dialects.Footnote 14 It should also be noted that Harakka was also a surname in Border Karelia and Viena Karelia; in Viena it was later formalised as Sorokin. According to previous research, the name may have been inspired by the use of the bird name ‘magpie’ to describe a frivolous or chattering person (Karlova Reference Karlova2015; see also Patronen Reference Patronen2017:487–488 and the references therein). Thus, it is possible that calling a cow by this name would have been motivated by a humorous view of the cow’s character.Footnote 15

6.2 Russian-origin cow denominations

The Russian-origin cow denominations recorded in the Dictionary of Karelian (KKS) generally describe the colour of a cow. According to the KKS, there have not been Russian-origin denominations based on the colour of a cow in the Viena and South Karelian dialects. Most of the denominations based on colour are recorded in Olonets Karelia, but this only reflects the uneven distribution of the data amongst the Karelian regions. The Russian-origin cow denominations of the KKS are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Russian-origin cow denominations in the Dictionary of Karelian (KKS)

Although the denominations describing the colour of a cow are recorded only in Olonets Karelia, they are not specific solely to Livvi-Karelian. Pesroi also occurs as a proper name for a cow in Border Karelia, and variants of bel’ k ka (pelkka ∼ belkkä, also belkko) have been used to describe at least white horses and dogs in various parts of Karelia (KKS s.v. pelkka). The cow denomination bel’ k ka, however, occurs only in Olonets Karelia, which is noteworthy as it is a common Russian zoonym. The denomination buurakko, on the other hand, has been used in the South, Border, and Livvi-Karelian areas to describe something of a dark or greyish-red colour in general and perhaps also cows of this colour, but this is not clear from the data. As shown above, the -kkO suffix is most typical of South Karelian. The Border and Livvi-Karelian recording sites of the name Buurakko are located in the vicinity of the South Karelian region.

Table 2 clearly shows that the KKS contains only a small number of denominations recorded in the Tver, Tikhvin, and Valday regions. However, buura < Russ. buryy, describing ‘a dark or greyish brown cow’, is recorded in Tver, and siivoi (< North Russ. sivoi < Standard Russ. sivyy ‘ash grey’), describing ‘a grey cow’, has been recorded in the Valday region. puura ∼ buura ∼ buuru is a denomination for ‘a chestnut horse’ throughout the Karelian region (KKS s.v. puura). Although cows have been described as buura only in Tver, a cow hue of this type was probably not uncommon in the South, Border, and Livvi-Karelian areas either, since in all of them either the name Buurikki ∼ Buuroi or the denomination buurakko has been recorded. Moreover, a brown cow has also been called bur (gen. buran) in the Vepsian area (SVJA s.v. bur).

On the other hand, names or denominations based on the Russian adjective sivyy ‘ash-grey’ do not occur in other dialect areas. In the Tver, Tihkvin, and Valday regions, the Russian-origin name siivoi also describes ‘a grey horse’.Footnote 16 Elsewhere in Karelia there have been no Russian-origin denominations describing a grey cow, except for the partly Russian-origin denominations pästärkarvu and harmoapäistärikkö < Russ. pazder ‘shive, splinter’ (SES s.v. päistär), which mean ‘a grey cow’. The Russian denominations describing a grey horse are based on the Russian adjective seryy, which is a generic adjective for grey, as opposed to the more specific sivyy. It is therefore possible that in the language islands the cows and horses can have greyish colourings that are not found in the northern Karelian-speaking areas. However, grey cows of some shade have also been found further north and they have been described in Olonets and Border Karelia by such original denominations as harmi (< Kar. harmua ‘grey’), hiirikki, and hiiroi (< Kar. hiiri ‘mouse’), and in Olonets Karelia by the proper name Harmoi (< Kar. harmua ‘grey’). There are no original denominations describing grey cows in the language islands, which may indicate that grey cows were not yet present in the Ladoga area at the turn of the seventeenth century. It should be noted, however, that this may only be due to the general scarcity of data recorded in the regions.

In Olonets Karelia, the Russian-origin denomination šiiboi has been used to describe ‘a sulky cow’. The denomination is metaphorical, since it is most probably based on the Russian ship ‘thorn, pin’ (cf. Kar. šiippa ‘a protruding part, branch: twig, thorn, etc.; derogatorily of limbs’, šippa ‘thorn, pin, dowel’, čiippa ‘branch of a plant, thin part coming from the ground or from an object; human limb’). The metaphorical connection between the words meaning ‘sulky’ etc. and the concrete ‘thorn, branch’ is also shown by the expressions šiipakko ‘branching; grumpy’ which are similar to the denomination šiipoi and phonetically different from the root word šiirakk|a, -o ‘branching; cranky’, šiilakko ‘branching; irritable, petulant’, čiihakk|a, -o ‘irritable, prickly; quarrelsome, petulant, angry’, čiirakk|a, -o ‘crotchety, irritable’, and the verbs šiipakoittuo ‘to become irritable, petulant’ and čiihakoittuo ‘to become irritable; to get angry, to tease’.Footnote 17 Most of these words also have a meaning related to drought or dehydration. There are no other records concerning the use of the denomination šiiboi in the KKS and hence it may be a local peculiarity, though not necessarily limited to describing the character of cows. All in all, the data show that cows have been described by Russian-origin denominations in a variety of ways.

7. Russian-origin cow names and denominations in the interview data

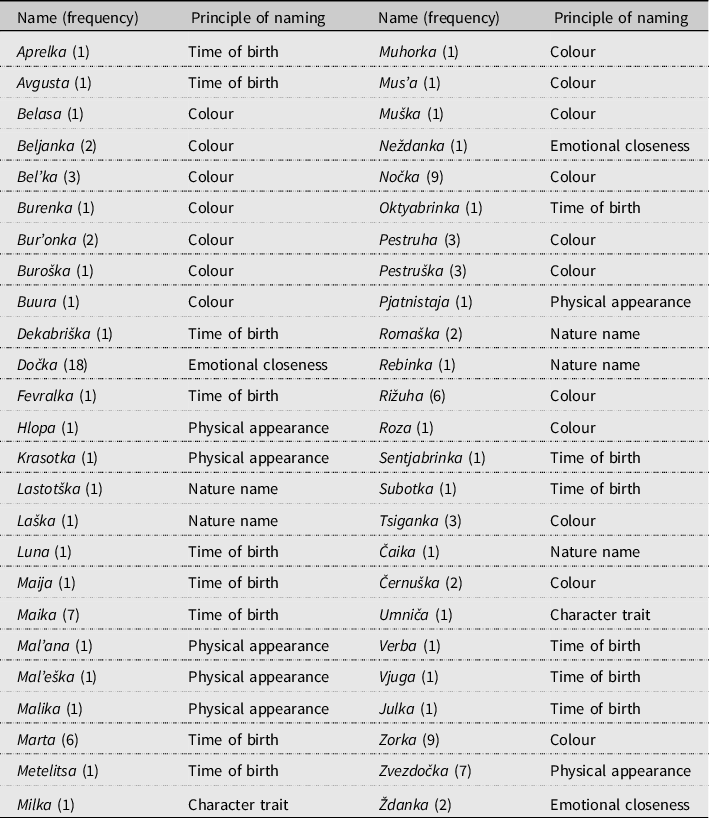

The cow names collected in Olonets Karelia and in the Tver region in 2012–2018 are mainly of Russian origin. The interviewees were mostly of retirement age, but the cow names used both in the respondents’ childhood and in modern times are, for the most part, characteristically generic Russian. The data recorded in Olonets Karelia are displayed in Table 3, and the data recorded in the Tver region in Table 4.

Table 3. Russian-origin cow names recorded in Olonets Karelia in 2012

Table 4. Russian-origin cow names recorded in the Tver region in 2016 and 2018

As the tables show, the interview data consist of names based on the time of birth, colour and physical appearance, and also character traits. The data also include nature names, and names given according to the emotional closeness felt towards the cow. Cows have also been named and referred to based on these principles in the KKS data, and these types of names are therefore well suited to comparisons of names of different ages.

It is worth noting that the change in the onomasticon may reflect the adoption of an entire naming system from the Russian side, and there may not be much in the current onomasticon that makes it characteristic of Karelians. In this article, I will look only at Russian-origin names and therefore the change in the onomasticon may mean, for example, the disappearance of Karelian derivative suffixes from the Russian-origin names, or the more pronounced Russianness of the Russian-origin names that were otherwise adapted into Karelian.

In the interview data the dominant principles of naming are the time of birth and colour: in the whole data set (f = 53) there are 16 cow names based on the time of birth and 17 names based on colour. The sub-data sets that I collected in Tver and Olonets Karelia are slightly different in size, but both of them have the highest number of names based on the time of birth and colour. As shown in Section 6.1, the time of birth is also the most common naming principle in the KKS data.

In contrast to the KKS data, in the interview data the names based on the time of birth do not generally reflect the day of the week on which the cow was born. In fact, there is only one exception, Subbotka < Russ. subbota ‘Saturday’. Rather, names based on the time of birth usually indicate the month of birth, and occasionally also the weather at the time of birth. It has been particularly common to name a cow born in May according to the month of birth: in the Tver sub-data there is Maika and in the Olonets Karelia sub-data Maija, Maika, and Maikki < Russ. mai, the latter combining the Russian month name and the Karelian derivative suffix -kki. It should be noted that Maija and Maikki are also Karelian hypocorisms of the anthroponym Mariya (Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2017b:122), which may have influenced their popularity as cow names, even if the informants claim that the principle of naming was the month of the cow’s birth. Naming a cow with an anthroponym is quite common in contemporary Karelia (see Section 5), which argues for the overlap of birth date and anthroponym in the criteria for the above-mentioned names.

There are also several occurrences of the name Marta < Russ. mart, meaning ‘born in March’. There are only a few names derived from other birth months, and most of these are from the same Tver Karelian informant who had worked as a veterinarian, e.g. Fevralka < Russ. fevral’ ‘February’ and Dekabriška < Russ. dekabr’ ‘December’. The names based on the month of birth are entirely Russian and do not contain, for example, Karelian phonetic elements. In a similiar way, the names Vjuga < Russ. vyuga ‘snowstorm’, Metelitsa < Russ. metel’ ‘snowstorm’, and Luna < Russ. luna ‘moon’, which otherwise describe the time of birth, are entirely Russian.

The different colours of cows are well illustrated by the colour-based names in the interview data. In Tver, a brown cow can be called by at least the Russian names Buroška, Bur’onka, and Burenka < Russ. buroi ‘brown’. As shown above, according to the KKS, the name for ‘a brown cow’ in Tver was buura, but in the other Karelian-speaking regions the name was not used for a cow (in Vepsian, on the other hand, it was). I recorded the proper name Buura in Tver, which may indicate the preservation of the old name and the development of the denomination into a call-name. The most frequent colour-based name in the interview data is the reddish-brown cow’s name Zorka < Russ. zorya ‘morning/evening glow’. In Tver I have also recorded the name Rižuha < Russ. ryzhiy ‘red-brown’ describing a red-brown cow. The name Roza ‘rose; pink’ has also been used to describe a cow in Tver and in Olonets Karelia. The brown or reddish colouring of the cow seems to be quite common according to the frequency of the names.

Like Buura, the name Bel’ka < Russ. belyy ‘white’ for a white cow I recorded in Tver already appears in the KKS data, although not in Tver but in Olonets Karelia. In my opinion, however, this does not indicate the antiquity of the name, since it was probably borrowed from Russian separately in different regions (cf. Bur in Vepsian). In Tver, a white cow has also been called by the entirely Russian names Belasa and Belyanka. On the other hand, I have recorded in Olonets Karelia the cow name Beloi, which appears in the KKS’s Olonets Karelian material as the name of a white horse, although in the Ludic (and Vepsian) areas the variant Bieloi was specifically a cow name.

In the KKS data recorded in Olonets and Border Karelia the Russian-origin name for ‘a variegated cow’ is Pesroi < North Russ. pëstroi < Standard Russ. pëstryy ‘variegated’. In Tver I have recorded the Russian-origin names Pestruha and Pestruška, which are derived from the same adjective. In Olonets Karelia, on the other hand, I recorded only the original name Kirjoi, although the Russian-origin equivalent has long existed in the region.

KKS does not contain Russian-origin names or denominations describing ‘a black cow’, but all names are of Karelian origin (e.g. Mussikki < Kar. musta ‘black’, Hiilikki < Kar. hiili ‘coal’). According to the interview data, a black cow has been called by a variety of Russian names, not all of which are based on an adjective describing the colour black. This may reflect the prevalence of black cows, on the one hand, and the differences between Russian and Karelian naming conventions on the other: original names are usually derived from an adjective describing the colour. I have recorded the names Nočka < Russ. noch ‘night’ and Tsiganka < Russ. tsygan ‘romani’ in Tver, and the name Černuška < Russ. chërnyy ‘black’ in Tver and Olonets Karelia.

In addition to colour, the physical appearance of the cow has sometimes been used as a naming principle in the interview data. Cows have been especially often named after the mark on their forehead (for such names see also e.g. Leibring Reference Leibring2002:84–85, Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2005:133): in Tver I have recorded the name Zvezdočka < Russ. zvëzdochka ‘star’ a total of seven times. The name parallels the Russian-origin name of a star-foreheaded cow, Plekko, recorded in the South Karelian dialects (see Section 6.1) and the Karelian names Tiähti, Tähtikki, and Tähikki < tiähti ∼ tähti ‘star’, recorded in Viena and Border Karelia (see the KKS). A cow which, according to a Tver Karelian informant, had five spots in its colouring, was called Pyatnistaya, apparently combining the Russian numeral pyat’ ‘five’ and the Russian feminine adjective pyatnistaya ‘spotted’.

Both in Tver and in Olonets Karelia, the diminutive Dočka < Russ. doch ‘daughter’ has been the most frequent of all cow names. It refers to the close relationship between the cow and the owner, and it can probably be traced back to the time of name-giving: names are often given when the cow is a small calf, and thus it is understandable that they would have been given diminutive names referring to small size (see also Leibring Reference Leibring2000:369). In Tver, calves have also been named Mal’ana, Mal’eška, and Malika < Russ. malen’kiy ‘small’, which parallel the name of a small cow recorded in Olonets and Border Karelia, Pienikki < Kar. pieni ‘small’ (KKS s.v. pienikki). According to Kuzmin (Reference Kuzmin2018b:101), such cow names were originally Karelian and Russian pre-Christian women’s names that were ‘reduced’ to cow names with the advent of Christianity.

The cow names Žnada < Russ. zhnada ‘desired’ and Neždanka < Russ. nezhnada ‘undesired’, both of which I recorded in Tver, belong to the above-mentioned group of pre-Christian female names. The nature names Čaika < Russ. chaika ‘seagull’ and Lastotška < Russ. lastochka ‘swallow’, also recorded in Tver, have likewise been used as anthroponyms. It is noteworthy that such old-fashioned cow names, which carry echoes of pre-Christian anthroponyms, are still used in present-day Tver. In both Tver and Olonets Karelia I have recorded the name Krasotka < Russ. krasivyy ‘beautiful’ describing ‘a beautiful cow’, which parallels the Karelian cow names Kaunikki, Kaunikoi, and Kaunoi < Kar. kaunis ‘beautiful’ (KKS s.v. kaunikki, kaunikoi, kauno[i]). Kuzmin (Reference Kuzmin2018b:102) suggests that such names are also based on Karelian and Russian pre-Christian female names. In the pre-Christian period, people were named according to their time of birth, external characteristics, and desirable traits, i.e. according to the same principles as animals (Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2018a). Thus, most of the cow names and denominations in both the KKS and the interview data may be consistent with earlier anthroponyms. Overall, however, the cow names in the interview data show clear structural, lexical, and partly also substantive differences from the Russian-origin material in the KKS.

8. Russian-origin cow names through the ages

This article has examined the Karelian cow names and compared two different data sets from different decades. The aim has been to provide an overview of Karelian cow names, with a special emphasis on their increasing Russianness. The comparison of the data from different periods interestingly displays a clear diversity of Russian-origin cow names but also clear similarities between the names.

It can be deduced from the analysis that the Dictionary of Karelian (KKS) contains a large number of cow names and denominations of Russian origin that have been phonologically and morphologically adapted to use in the Karelian language. Many of these names and denominations reflect the same phonetic correspondences as the wider range of Slavic loanwords in Karelian. The most obvious signs of their adaptation to Karelian are their Karelian suffixes, the quality of their first syllable vowels, and the voicelessness of voiced sounds.

Historically, the language sociological situation in the Karelian-speaking areas has been diverse: Karelian has been influenced by Russian for a long time, but the intensification of contact and the population’s increasing proficiency in Russian have contributed to the introduction of new Russian-origin vocabulary. The longer the Russian loanwords have been in Karelian, the more they have had time to adapt to the Karelian phonetic system. Recent loan vocabulary, on the other hand, displays source language features more directly. Parallels in other Finnic languages may indicate the antiquity of the name or denomination and point to an early date of borrowing, but loans confined to eastern Finnic languages in particular may be later, separate loans.

In addition, analysis has revealed that the time of birth is the most common principle of naming a cow in the Russian-origin data included in the KKS. Similar names based on the day of the week of birth are recorded in all of the Karelian-speaking regions except for the language islands, although sometimes it is uncertain whether the day of the week is the underlying reason for the name. A considerable number of cows have been named after their colour, and also more than half of all the denominations in my data are based on colour. Naming according to time of birth reflects a close relationship with the cow, as it is a principle of naming that is not transparent to people other than those who know the cow. On the other hand, naming by colour distinguishes cows from one another in a more general way, and it is not necessary for the owner to know anything more about the cow than its appearance.

Some of the Russian-origin denominations based on colour or physical appearance are widely distributed in Karelian-speaking regions and also in neighbouring areas, while others occur within a very limited area. The names recorded in diverse regions differ mainly in terms of their phonological and morphological features, which also otherwise distinguish the dialects of Karelian from each other.

As for the interview data, the names collected in the 2010s reflect an unambiguous, general Russianness, and the phonological and morphological adaptation to the Karelian language is less pronounced than in the KKS data. However, even in the interview data the main principles of naming cows are colour and the time of birth. The shift from pre-Christian anthroponyms to cow names can be seen in the onomasticon describing the character traits and appearance of the cow in the interview data. Naturally, the interview data also show the adaptive tendencies of Slavic loanwords that are already visible in the KKS data.

To conclude, the principles of naming are preserved even if the linguistic composition of the onomasticon changes. The KKS data clearly show that the principles of naming have in part remained unchanged from the oldest records down to the present day. From earliest days, time of birth, character traits, colour, and other external characteristics of the cow have been used as building blocks for the names used. Moreover, the principles of naming underlying the Russian-origin cow names correspond to the wider range of European cow names (e.g. Leibring Reference Leibring2000, Reference Leibring2002, Reference Leibring2021; Reichmayr Reference Reichmayr2005, Reference Reichmayr2015; Faster & Saar Reference Faster and Saar2021). In general, then, the findings of this article shed further light on the Russianness of Karelian cow names, contribute to the continuum of research on both cow names and Karelian–Russian contacts, and serve as a firm basis for a broader study of Karelian zoonyms.