1. Introduction

This article examines certain orthographic features in a set of letters written in the 1920s and 1930s in Finnish by Kvens, an ethnic and linguistic minority group living in the Northern Norwegian counties of Troms and Finnmark. According to the 1930 Norwegian census, which registered both language and ethnicity, Kvens in these two counties numbered almost 11,000 (Hyltenstam & Milani Reference Hyltenstam and Milani2003:5). We focus on orthographic features that demonstrate the writers’ multiliteracy in Finnish and Norwegian, and even in Northern Sámi. While some write in a manner approaching the assumed norms of the Modern Written Finnish (MWFFootnote 1 ) of the time, others deviate from it by using non-standard orthography or characters from the Norwegian alphabet. We attribute these differences in writing to various factors: age, place of birth, education, socioeconomic status, access to texts in MWF, religious affiliation, and bilingualism in Norwegian and/or Northern Sámi. The orthography in these letters thus reflects isolation from the developments that occurred in written Finnish in Finland during the nineteenth century. This isolation led to the creation of the written variety of Kven after 2005, as many Kven minority members do not identify with MWF as their form of written language.

Written Finnish, often called ‘Bible Finnish’, was first developed during the sixteenth century. The three periods of written Finnish are as follows:

-

1. Old Literary Finnish (OLF, ca. 1540–1810)

-

2. Early Modern Finnish (EMF, ca. 1810–1880)

-

3. Modern Written Finnish (MWF, ca. 1880 onwards)

The period of OLF belongs to the time when Finland was under Swedish rule (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen2015). The nineteenth century, which was characterized by nation-building across Europe (Gellner Reference Gellner1983, Wright Reference Wright2004), witnessed the transformation of the Finnish language from one used primarily by common folk to communicate their daily and religious needs to one capable of being used in all domains of society. Written Finnish during this period is referred to as Early Modern Finnish (EMF). In tandem with this development a new political situation developed: Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia in 1809. To meet these new societal demands, thousands of new words were created, and a new standard language was crafted to be shared by all Finns, regardless of the local dialect they spoke at home. Use of this new standard was transmitted both via literature and primary schools (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994, Kauranen Reference Kauranen2013, Lauerma Reference Lauerma2013:158). During the period of EMF, religious literature often retained its earlier form, however. Therefore, the view that written Finnish developed rapidly in the nineteenth century is based primarily on its development in the domain of secular literature (Lauerma Reference Lauerma2013:159–160, Reference Lauerma2018). According to the established view, the period of EMF lasted until approximately 1880 (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994:15). However, new research on EMF demonstrates that this period possibly lasted longer (Nordlund Reference Nordlund2018:578).

Two competing language planning ideologies existed during the period of EMF. One of them followed a language ideology emphasizing uniformity, the other the use of dialect when writing Finnish. The latter ideology lost support, and MWF language planning followed a language ideology stressing homogeneity, thus allowing for little variation in form (Paunonen Reference Paunonen, Nyman, Länsimäki and Yli-Vakkuri1992, Laitinen & Nordlund Reference Laitinen and Nordlund2013:179, Nordlund & Pallaskallio Reference Nordlund, Pallaskallio, Anita Auer, Palander-Collin and Säily2017:113). By contrast, written language during the EMF period, and especially that produced by writers among the common people during the nineteenth century, was of a much more heterogeneous variety (Lauerma Reference Lauerma2008, Nordlund & Pallaskallio Reference Nordlund, Pallaskallio, Anita Auer, Palander-Collin and Säily2017).

The question of how Kvens wrote in Finnish has received little attention in the literature up to the present. One exception is Maliniemi (Reference Maliniemi2010), which discusses archival documents in Norway produced in the context of a municipal administration, including letters written in Finnish by Kvens. However, these letters were written in a context quite different from that of the letters in our study, which were written at the request of ethnographers Samuli and Jenny Paulaharju, and which can thus also be classified partly as private correspondence. Maliniemi’s study also focuses primarily on the content of the letters examined, while our focus is on orthography. This study is thus the first of its kind to analyze how Kvens wrote in their language in the 1920s and 1930s in an in-depth and systematic way.

We seek answers to the following research questions:

-

How did multilingualism influence orthography for Kvens writing in Finnish?

-

What resources were available to Kvens in their writing?

-

What is the relationship between reading and writing among the Kvens?

Section 2 gives some background on the linguistic situation of Kvens in isolation from developments in Finland and presents research on letter writing in historical sociolinguistics. Section 3 introduces the set of letters analyzed in this study as well as the people who wrote them, and also gives an overview of the methods used. Section 4 presents the orthographical features in focus in the letters and their use. Section 5 discusses the results, and Section 6 presents the conclusions of the study.

2. The Kvens writing in isolation in a multilingual environment

The linguistic developments in Finnish that occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Finland, where the Kven people trace their linguistic roots, were not implemented among the Kvens. This section discusses reasons for this isolation, and especially the possibility of making literature in Finnish accessible to Kvens (see especially Section 2.2). We also discuss Kvens’ motives for letter writing and compare them to those found in letter writing in historical sociolinguistics (Section 2.3). First, we give a short introduction to the Kven minority in Section 2.1.

2.1 The Kven minority in Northern Norway

Hyltenstam & Milani (Reference Hyltenstam and Milani2003:2) give the following definition of the Kvens (our translation):

All with a Finnish language and cultural background who moved to Norway before 1945, and their descendants, provided that this background in one way or another is perceived as relevant today.

The term KvenFootnote 2 can be found in historical sources in Norway referring to Finnish-speaking people. Kvens moved to Norway from Northern Sweden and Finland for the most part in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, some of them even earlier (Niemi Reference Niemi, Bonnevie Lund and Bolme Moen2010). Kven dialects are close to the Far North Finnish dialects spoken in the areas where Kvens originated (Lindgren Reference Lindgren1993, Lindgren & Niiranen Reference Lindgren and Niiranen2018).

The number of Kvens increased toward the end of the nineteenth century. In the two northernmost counties of Norway, Finnmark and Troms, Kvens comprised 25% and 8% of the total population in 1875, respectively. In some local villages, such as Vadsø, Kvens made up as much as 60% of the total population (Niemi Reference Niemi, Bonnevie Lund and Bolme Moen2010:43–44). Multilingualism in Kven and either Norwegian or Northern Sámi, or even trilingualism in all three languages, was common in many villages in Troms and western Finnmark. However, in some local settlements, especially in eastern Finnmark, Kvens often lived in monolingual villages (Aikio Reference Aikio1989, Lindgren Reference Lindgren, Lindgren and Bull2009, Lindgren & Niiranen Reference Lindgren and Niiranen2018). Many Kvens lost their language, especially during the period between the two world wars because of Norway’s harsh assimilation policy (Lindgren Reference Lindgren, Lindgren and Bull2009:114–115). Among those who wrote to the Paulaharjus, many had multilingual backgrounds. Some also sent letters to the Paulaharjus in Norwegian, while others mention sending in submissions to Norwegian newspapers. Our biographical research has also revealed that several letter writers were prominent members in their communities, and therefore must have been fully bilingual in Norwegian and Finnish.

However, the Kven people were not recognized as a national minority group in Norway until 1998, and the Kven language only received status as a national minority language in 2005. Since 2005, a new written standard based on Kven dialects has been developed for the language, and guidelines for its use were published in 2012 (Keränen Reference Keränen2018:7). Even among Kvens today there exists no uniform agreement about the use of the term Kven and the status of Kven as a distinct language. Some, especially those living in eastern Finnmark, prefer the term norskfinsk (‘Norwegian Finnish’) to refer to themselves (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2020). Nevertheless, there exist sociolinguistic, cultural, and political reasons to consider Kven to be a distinct language from Finnish (Hyltenstam & Milani Reference Hyltenstam and Milani2003), and the majority view today is to treat it as a separate language.

The letters in our study were written long before the recognition by the Norwegian government of the Kvens as a national minority and the language as a distinct minority language. Even though the use of the term Kven to refer to those of Finnish background had already long been in use at that time, the language they spoke was referred to differently by different groups of people. The Norwegian government used the term Kven to refer to the language in the original draft of the 1936 School Law (Seppola Reference Seppola1996:30), but several of the letter writers in our study explicitly refer to the language they wrote in as Finnish, and none of them refer to the language as Kven. Given this state of affairs, and for the sake of simplicity and uniformity, we adhere to the use of the term Kven when referring to the identity of the writers, but we use the term Finnish when discussing the language they used in their letters. However, when referring to oral language use, we use the term Kven dialects.

2.2 The separation of Kvens from the linguistic developments in Finland

Although the geographical distance between the various Kven speech communities in Northern Norway and Finland’s border is not great, general literacy in Finnish did not spread among Kvens the same way it did among Finns in Finland, where it increased rapidly at the end of the nineteenth century (STV 1903:table 15b; for the development of literacy in Finland see e.g. Kauranen Reference Kauranen2013, Laine Reference Laine, Sinnemäki, Portman, Tilli and Nelson2019). This situation increased the linguistic diversification between Kven dialects and their contact dialects in Finland, as written Finnish influenced the Far North Finnish dialects in Finland, but not Kven dialects. Instead, they were influenced by the majority language Norwegian, as well as by Northern Sámi (Lindgren & Niiranen Reference Lindgren and Niiranen2018). This proves the well-known fact that national borders can and often do serve to isolate speech communities (e.g. Palander, Riionheimo & Koivisto Reference Palander, Riionheimo and Koivisto2018).

Additionally, the government-backed assimilation policy of Norwegianization, which had as its explicit aim suppression of the identity and language of national minorities in Norway and assimilation of these populations into the dominant Norwegian-speaking population, also meant that the Kvens became isolated from the linguistic developments in Finland. This assimilation policy began in the 1850s and lasted until the beginning of World War II. Despite this policy being in effect, Kven children were nonetheless able to learn to read in their own language (Eriksen & Niemi Reference Eriksen and Niemi1981:48–49).

The goal of teaching Kven students to read in Finnish was primarily based on religious arguments and to support the learning of Norwegian in the nineteenth century. The Norwegian authorities also produced some teaching materials for minorities (Dahl Reference Dahl1957:196–198, 245–248). Paulaharju (Reference Paulaharju1928:524–525) points out that students still developed the ability to read Finnish for as long as bilingual books were still in use in schools. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the policy of Norwegianization in schools was enforced more stringently, and the use of Finnish at school was reduced to a minimum (Dahl Reference Dahl1957:240–243, Eriksen & Niemi Reference Eriksen and Niemi1981:53–58, Niemi Reference Niemi, Brandal, Alexa Døving and Thorson Plesner2018:140–142). With the advent of the School Law of 1936, the use of Finnish as a helping language was no longer allowed (Sannhets- og forsoningskommisjonen 2023:222, 449).

Despite this assimilation policy, many Kvens still had contact with written Finnish, especially via their participation in religious activities. Many Kvens belonged to the pietistic religious movement of Laestadianism, which emphasized reading of religious literature in Finnish, both individually and in religious meetings (Niiranen Reference Niiranen2019, Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen2020). In addition, the Norwegian Lutheran church was obligated to arrange services in Finnish for Kvens (Beronka Reference Beronka1923:20–22, 51, 54). Minority languages could also be used in confirmation instruction (Maliniemi Reference Maliniemi2010:22–24). However, beginning in 1910, successive bishops of the Norwegian Church in Tromsø shared the ideology of Norwegianization (Sannhets- og forsoningskommisjonen 2023:239, 255).

Kvens owned mostly core religious books in Finnish such as catechisms, psalm books, and Bibles, but also possessed other kinds of religious books popular in Finland, as attested to by their many printings (Niiranen Reference Niiranen2019). Even though it is reasonable to assume that many Kvens were able to read in Finnish, we suspect that most Kvens received little if any formal instruction in writing their language in Norway. Also, many of the Kvens who moved from Northern Finland in adulthood at the end of the nineteenth century most likely did not learn to write in Finnish, because only a few primary schools had been established in this part of Finland prior to the 1890s (Lassila Reference Lassila2001).

2.3 Research on letter writing in historical sociolinguistics

Collections of private letters dating as far back as the seventeenth century exist in many European languages and paint a picture of how ordinary people wrote. During the nineteenth century, letter writing became more common among the general populace. One contributing factor was migration. Also, people lacking any formal instruction in writing wrote letters to their family members to keep in contact with them. Such letters have been collected in many European languages (e.g. Elspass Reference Elspass, Hernández-Campoy and Conde-Silvestre2012:159–160, Laitinen & Nordlund Reference Laitinen, Nordlund, Dossena and Del Lungo Camiciotti2012, Kauranen Reference Kauranen2013, McCafferty Reference McCafferty2017, Hickey Reference Hickey2019).

Research on literacy development during ‘the long nineteenth century’ – from the French revolution to World War I – has been of interest to both historians and linguists in Nordic countries since the beginning of the new millennium. Those who learned to write on their own have been dubbed self-taught writers and have also been studied both by linguists and historians in Finland and other Nordic countries (Fet Reference Fet2003, Kuismin & Driscoll Reference Kuismin and Driscoll2013a, Laitinen & Mikkola Reference Laitinen and Mikkola2013, Keravuori Reference Keravuori2019). Such writers have also been studied more broadly in Europe (Lyons Reference Lyons2013). These studies of literacy have yielded new insights into the development of writing ability among common people in these countries before the advent of general literacy. Crucially, they present a history of literacy from below, as they shed light on the writing of people without formal education or high positions in society (Kuismin & Driscoll Reference Kuismin and Driscoll2013b:7).

Nonetheless, self-taught writers were still in contact with written language. Many such writers were able to read, especially in Finland as well as in Sweden and Norway, where the Lutheran church focused on teaching reading (Kuismin & Driscoll Reference Kuismin and Driscoll2013b:7). According to Liljewall (Reference Liljewall2013), the reading of religious texts could be transformed into a functional ability to read, and even further into full literacy including the ability to write. Both religious and secular texts functioned as models for self-taught writers. People became accustomed to written language not only via reading, but also via listening to someone read aloud, a practice common in earlier times (Lyons Reference Lyons2010), and common among the Kvens (Niiranen Reference Niiranen2019).

The emigrant letters that have been investigated in historical sociolinguistics, especially those written by the lower classes, are often private letters (Laitinen & Nordlund Reference Laitinen, Nordlund, Dossena and Del Lungo Camiciotti2012, McCafferty Reference McCafferty2017, Hickey Reference Hickey2019:5). However, the letters in our study were written at the specific request of the Finnish ethnographers Samuli (1875–1944) and Jenny (1878–1964) Paulaharju, asking for information about their own lives or the lives of other Kvens in their communities. The writers had roles as informants and answered questions sent to them especially by Samuli Paulaharju. Even though the role of informant is important in many of the letters, other motives exist as well. The letters to the Paulaharjus demonstrate that it was important for the Paulaharjus to keep in touch with the people they had become acquainted with during their travels to Northern Norway, even after the visits had concluded (see Kauranen Reference Kauranen2013:46–48). Very often the letter writers express thanks for letters, postcards, photos, or gifts that they received from the Paulaharjus. They invite the Paulaharjus to visit them, and some also write about their plans to visit the Paulaharjus in Oulu, Finland. Other private motives include ordering different items from the Paulaharjus, such as books, newspaper subscriptions, and even articles of clothing. Writers even asked to have Samuli Paulaharju’s book Ruijan suomalaisia (The Finns of Ruija) sent to them after it was published. Finally, they inform Samuli Paulaharju how his book was received in Norway. In addition, health and weather are often discussed in letters, and these are typical topics found in private letters (see Rutten & van der Wal Reference Rutten and van der Wal2012). In this respect, these letters are different from the more official-seeming letters informants wrote to organizations such as the Finnish Literature Society (Mikkola Reference Mikkola2009:97–99, Reference Mikkola2013:342–343).

In our study we focus on the differences seen in the orthography of writers with heterogeneous backgrounds. We discuss the resources different individuals may have had available to them when writing, for example various Finnish texts possibly representing different periods of written Finnish which could have functioned as models. We also discuss how multilingualism and knowledge of the Norwegian written language may have impacted their writing.

3. Data and methods

3.1 Data

The materials in this study consist of 56 letters and postcards (approximately 15,000 words) written to the Finnish ethnographer couple Samuli and Jenny Paulaharju primarily between the years 1927 and 1931, with three letters written somewhat later, in 1937, 1940, and 1944. The letters are archived at UiT The Arctic University Museum of Norway and are copies of the original letters located at the Oulu branch of the Finnish National Archives in Finland.

Twenty-nine different letter writers wrote to the Paulaharjus, 19 of them men and 10 women. Two of the letters were signed jointly by married couples, and thus far we have been unable to determine which of the signees wrote the letters in question. The writers were born between 1848 and 1916, and all were residents of the counties of Troms and Finnmark at the time of writing. Seven of the letter writers were born in Finland and immigrated to Norway, while the remainder were born and raised in Norway. Of the Norwegian-born writers, all but one had Finnish ancestry.Footnote 3 For many of them, one or both parents were born in Finland, while for a few the connection to Finland lies even farther back in time. Although all the letters in our study were written in Finnish, it is known that at least three of the letter writers also wrote to the Paulaharjus in Norwegian as well (Brev til Samuli Paulaharju, Brev til Jenny Paulaharju).

Seven of the writers (all women) wrote to Jenny Paulaharju, while the remainder wrote to Samuli Paulaharju, or to the couple jointly. From the content of the letters, it is clear that many of the letters were written specifically at the Paulaharjus’ request, in response to queries sent earlier by the Paulaharjus about specific members of the Kven community known to the letter writers. These requests were part of the Paulaharjus’ larger ethnographic project which involved documenting the lives of expatriate Finns, culminating in the monographs Ruijan suomalaisia published in 1928 and Ruijan äärimmäisillä saarilla (On the outermost islands of Ruija) in 1935.

3.2 Methods

Although most of the letters in our corpus are handwritten, a total of six writers typed at least some of their letters. Since the handwriting in some of the letters was very difficult to read, we transcribed the vast majority of the letters in the corpus, both in order to improve readability as well as to facilitate text searching. Optical character recognition (OCR) software was considered and piloted, but the results required an excessive amount of manual editing, rendering hand transcription the most expedient method. The handwriting in the letters also varied widely: some letters were quite easy to read and transcribe, while the penmanship of some writers, presumably self-taught and unaccustomed to writing, proved quite challenging to decode. We performed manual searches of the letters in order to look for particular words and patterns and collected these words for analysis.

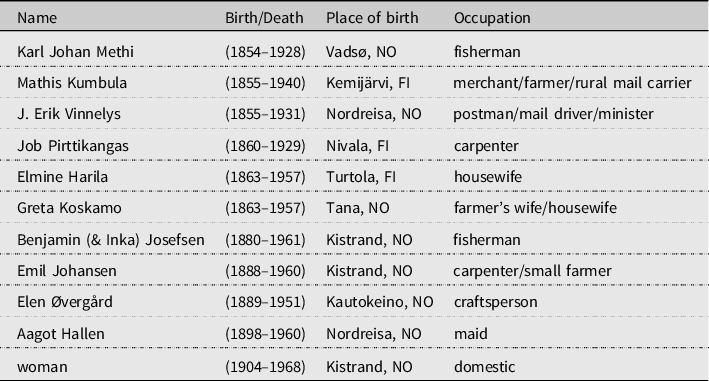

In performing biographical research on the letter writers, we made use of three main sources. First, we were able to locate all letter writers whose first and last names were available to us in the Norwegian national censuses, which have been conducted roughly every ten years and are available online (for the years 1920 and prior due to privacy concerns) at the Digital Archives (DA), a service of the Norwegian National Archives. Not only did we find all the letter writers in the Norwegian census records, in many cases we also researched their families further back in time, in order to determine their connections to Finland. Second, the precise connection to Finland for many was made by locating either the letter writers themselves – in the case of immigrants – or their parents or grandparents in the Finnish church records, available online in digitized format at the Finland’s Family History Association website. Third, Samuli Paulaharju’s monographs (Reference Paulaharju1928, Reference Paulaharju1935) include biographical information on many Kvens in the counties of Troms and Finnmark, and we were able to fill in details in the biographies of many of our writers using these two sources. Table 1 lists our letter writers, including birth and death dates, places of birth, occupations, and whether they wrote to Samuli Paulaharju (S) and/or Jenny Paulaharju (J). In accordance with Norwegian law and the agreement we signed with UiT The Arctic University Museum of Norway, the names of those who died less than 60 years ago have been omitted for the sake of privacy.

Table 1. Kven letter writers

a Petsamo (Pechenga in Russian) was not part of the Grand Duchy of Finland between 1809 and 1917 and only became part of the Republic of Finland in 1920 under the terms of the Treaty of Tartu. It was subsequently lost to the Soviet Union in 1944.

The four most prolific of these letter writers (marked in bold in the table) are the following: a man born in 1899 in Lyngen (3,457 words), Antti Seppä (2,230 words), Elmine Harila (1,182 words), and M. M. Mikkola (1,082 words). A handful of the letter writers were born in Finland, but the majority were born in Norway. The letter writers also belong to different generations, with birth dates ranging from 1848 to 1916. In addition, we also find clear distinctions in terms of socioeconomic classes among the writers, with some engaged in the traditional Northern Norwegian occupations of fishing and farming, while others were merchants, ministers, and office workers. There is thus a certain level of built-in diversity among our letter writers, in terms of both their education and life experiences. Taking all these factors into account, we aim to show how these individuals’ different backgrounds impacted and influenced their ability to write in Finnish, as evidenced by the letters available to us in our study.

Throughout this paper we employ a coding system to refer to the specific pages of the scanned letters cited in our corpus, for example (J147a) or (S13b), where the capital letter refers to the recipient of the letter (S = Samuli Paulaharju, J = Jenny Paulaharju), the number refers to the specific letter written by an informant, and the small alphabetic letter refers to a page within the specified letter. These number codes are identical to the codes used by UiT The Arctic University Museum of Norway in their collection (Brev til Samuli Paulaharju, Brev til Jenny Paulaharju), and form part of a larger collection of letters sent to the Paulaharjus, some of which were written in Norwegian.

3.3 Authorship

In research on letters, a question that arises is whether handwritten letters were actually written by the individuals whose signatures appear at the end of them (Hickey Reference Hickey2019:3). One can never be sure about who took pen in hand to write any given historical letter, but one normally proceeds under the default assumption that the person whose signature appears at the end of a letter is also the writer of the letter. However, we have uncovered evidence that at least one writer (Lovise Korbi) may have had one of her letters written by someone else. Figures 1 and 2 contain excerpts from the final pages of two letters signed by her and written ten months apart in 1928:

Original:

Ja sofialleki paljo terveisiä tätiltä nyt minulla [ei saa selvää] ja olkaa niin hyvät ja kirjatka älkää sitä kattoko että minä olen hijas sitä pytä Lovisa Korpi sanokaa miehellenneki terveisiä.

MWF:

Ja Sofiallekin paljon terveisiä tädiltä. Nyt minulla [ei saa selvää] ja olkaa niin hyvät ja kirjoittakaa, älkää sitä katsoko, että minä olen hidas. Sitä pyytää Lovisa Korpi. Sanokaa miehellennekin terveisiä.

English:

And many greetings to Sofia from auntie. Now I have [unclear text] and please write don’t look at how slow I am, requests Lovisa Korpi. Give your husband my greetings also.

Original:

Ei nyt muta ennän kuin sytämen rakkata terveiset teillen ia Soffialle ia ketä on [?] sielä jäkä hyvästi Jumalan armon haltun toivo

Kunnioituksella

Lovise Korbi

Gamlehje[m?]

Vadsø

MWF:

Ei nyt muuta enää kuin sydämen rakkaat terveiset teille ja Sofialle ja ketä on [?] siellä. Jääkää hyvästi Jumalan armon haltuun toivoo

Kunnioituksella

Lovise Korbi

Vanhainkoti

Vadsø /Vesisaari

English:

That’s about it, just warm greetings to you and Sofia and whoever is [?] there. May you stay in God’s grace from

With respect

Lovise Korbi

Old folks’ home

Vadsø

Figure 1. Letter written by Lovise Korbi to Jenny Paulaharju, dated 1 February 1928 (J163b).

Figure 2. Letter written by Lovise Korbi to Jenny Paulaharju, dated 27 December 1928 (J155b).

There are several ways in which the handwriting in these two letters differs. First, the writer’s name is spelled differently in the two letters. In the first letter, dated 1 February 1928, the writer signs the letter Lovisa Korpi, the Finnish version of her name, while in the second letter she signs it Lovise Korbi, the Norwegianized version where the word-final a in her first name has been replaced by e, and the word-medial p in her last name has been replaced by b. Second, the overall quality of handwriting in the first letter is less controlled, the lines slant downward, and the letter also contains errors that have been crossed out, while the handwriting in the second letter is straight, neat, and orderly. Finally, there are clearly observable differences in the formation of certain letters. Returning to the signatures, the s in the writer’s first name Lovisa/Lovise is completely different in the two letters. In the earlier letter, the writer used the Kurrent cursive style, where the cursive s has both an ascender and a descender, while in the second letter the s is formed in the modern way with neither an ascender nor a descender. Other words in this letter also illustrate this difference. Another conspicuous difference is the use of the letter ū for u in the second letter, as seen in the words mūta and haltūn (pro standard Finnish muuta ‘else’ and haltuun ‘in somebody’s keeping’). This phenomenon, discussed further in Section 4.3, strongly suggests the writer of the later letter was Norwegian-born and not Finnish-born. The Norwegianized version of the letter writer’s name in the second letter also points to a Norwegian origin for the writer. Finally, as Lovise Korbi was already 80 years old at the time these letters were written, we would expect her handwriting to either be the same in both letters, or, if anything, to deteriorate during the ten-month time span separating them, potentially due to age, illness, or infirmity. The fact that the second letter is written in a more controlled, orderly style of handwriting along with the other evidence above thus point to the possibility of a younger, Norwegian-born writer assisting an elderly person in her letter writing.

4. Deviations from standard orthography

In this section, we examine the deviations from standard Finnish orthography seen in the Kven letters. Orthography is a broad term and covers a wide spectrum of conventions for writing a language, including not only spelling, but also capitalization, punctuation, and the rendering of compound words (Coulmas Reference Coulmas2003:35, Seifart Reference Seifart, Gippert, Himmelmann and Mosel2006:277). We limit our investigation to the following three phenomena:

-

replacement of d with t,

-

use of b, d, g for p, t, k,

-

use of Norwegian characters.

The second two phenomena provide evidence for linguistic transfer from Norwegian, while the first, replacement of d with t, is a phenomenon also found among writers in Finland at the same time and reflects a certain lack of exposure to written texts in MWF.

4.1 Replacement of standard Finnish d with t

As is well known, the spelling system of Finnish is largely phonemic, and a rendering of Finnish in the International Phonetic Alphabet results in only minor divergences from the principle of one phoneme corresponding to one letter of the alphabet. The alphabet of Modern Written Finnish includes the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet plus the letters å, ä, and ö. The letters b, c, f, q, w, x, z, and å normally occur only in words of foreign origin. The letter g only occurs in native words in the sequence ng, where it breaks the generalization of one phoneme corresponding to one letter and represents the velar nasal as in sangen ‘very’.

The letter d (and phoneme /d/) is of particular interest, both due to its history and its restricted distribution in the modern language. In MWF it only occurs word-initially in loanwords, such as in delfiini ‘dolphin’ and dialogi ‘dialogue’. In native words, d only occurs word-medially, typically as the weak variant of t as a result of consonant gradation, a type of lenition triggered when adding certain suffixes to words, for example tietää (know.inf Footnote 4 ) but tiedän (know.1sg). However, MWF also contains a non-trivial number of words containing word-medial d that are outside the domain of consonant gradation, such as edes ‘even’, odottaa ‘to wait’, sydän ‘heart’, and edellinen ‘previous’ (Karlsson Reference Karlsson1983:58).

The modern-day phoneme /d/ as a weak variant of /t/ developed relatively recently, and in a fairly artificial way, from the earlier voiced dental fricative /ð/. Due to its occurrence only word medially, /d/ has been called a defective phoneme in Finnish (Karlsson Reference Karlsson1983:58). Both Finnish and Swedish originally had /ð/ in their phonemic inventories, and both languages originally represented it as dh orthographically, as can be seen in texts written in Old Literary Finnish. Over time the phoneme /ð/ became /d/ in Swedish, and orthographically this was reflected in a change from dh to d. In Finnish, however, there was no such systematic change of /ð/ to /d/. Instead, /ð/ was retained in a few Finnish dialects (such as near Rauma as well as the Northern Tornio dialect areas) until the early twentieth century, while in other dialects /ð/ was lost completely or replaced by /r/ (such as in the Southern Ostrobothnian dialect) or even /l/ (Rapola Reference Rapola1966:90). In no spoken variety did /ð/ become /d/, as was the case in Swedish. However, the orthography of MWF replaced the dh of OLF with d in parallel with the change in Swedish orthography from dh to d, leading to a situation where the Modern Written Finnish orthographic symbol d does not actually reflect the pronunciation of any modern spoken dialect. However, many speakers of modern Finnish now fully pronounce d due to influence from the written language.

Since the vast majority of the letter writers in our study either were born in Northern Finland or had roots in Northern Finland or Sweden, most of them would have been speakers of the Far North Finnish dialects, which typically lack the phoneme /d/ altogether. In these dialects, Modern Written Finnish uudenvuodenpäivä ‘New Year’s Day’ for example is pronounced as uuenvuojenpäivä, where d either is missing or represented by the glide j. We might expect that such speakers would do the same in their writing, and we indeed find evidence of such words in our corpus, e.g. lehen for MWF lehden (newspaper.gen) and vuoien for vuoden (year.gen). What is interesting is that some of the letter writers in our study instead use t for standard Finnish d, and some exhibit a good deal of inconsistency in representing t and d. Paunonen (Reference Paunonen, Sisko Brunni, Palviainen and Sivonen2018) analyzes a similar phenomenon in the speech (not writing) of Tornio Valley speakers of Meänkieli (a language closely related to Kven spoken in Northern Sweden) between 1966 and 1992, and suggests that the use of t for d is a type of hypercorrection: in a dialect without spoken d, the speaker or writer must make a decision about whether a given word contains d or t, and often incorrectly renders standard Finnish d as t. This makes sense if we assume these writers have some familiarity with written MWF: in their attempt to write words containing d, they instead use t, since phonetically these two sounds differ only in voicing. This is really no different than the more general practice of pronouncing words containing voiced plosives as voiceless, so that bussi ‘bus’ is pronounced identically to pussi ‘bag’ – a phenomenon still common in Finnish today (Jarva Reference Jarva1997). As our letters show, this can result in inconsistent rendering of standard Finnish t: at times it is rendered correctly, at other times not. The letter in Figure 3 by Lovise Korbi, born in 1848 in Paavola, Finland, is a prime example of this inconsistency:

Original:

Vesisaresta 27mäs Joulukuta 1928

Rakas rouva!

Sytämen rakkat kitokset lahjan etestä, en minä muta voi tehtä, vanha kuin olen, van rukoilen Jumalan siunausta teile ja teitän omille.

MWF:

Vesisaaresta 27. Joulukuuta 1928

Rakas rouva!

Sydämen rakkaat kiitokset lahjan edestä, en minä muuta voi tehdä, vanha kuin olen, vaan rukoilen Jumalan siunausta teille ja teidän omille.

English:

From Vadsø the 27th of December 1928

Dear Mrs!

Warm thanks for the gift, there’s nothing else I can do, as old as I am, than pray for God’s blessing for you and yours.

Figure 3. Letter written by Lovise Korbi to Jenny Paulaharju, dated 27 December 1928 (J155a).

As discussed in Section 3.3, there is some doubt whether Lovise Korbi actually wrote the letter above, given the divergence in handwriting between the two letters in our corpus purported to be written by her. However, the letter had to be written by someone who spoke the local Kven dialect, and the evidence discussed in Section 3.3 suggests the writer of this letter was someone born in Norway. Some of the divergent forms in the letter above are listed in Table 2, forms which at first glance suggest that standard Finnish d is systematically rendered as t. In each table the column ‘Lexical entry’ lists the nominative of nominals and infinitive form of verbs.

Table 2. Substitution of t for d by Lovise Korbi

However, upon further inspection it becomes clear that the phenomenon is not one of simply substituting every instance of standard Finnish d with t. The final line of the excerpt in Figure 3 gives concrete proof of the uncertainty that writers such as Lovise Korbi or her ghost writer faced regarding d vs. t. The first letter in the writer’s version of standard Finnish teille ‘to you’ (pron.2pl.all) begins with what looks like a combination of both a d and a t, suggesting that she first wrote one letter and then went back and wrote the other on top of it. The same is the case for her version of standard Finnish teidän ‘your’ (pron.2pl.gen), where one can see that she wrote both d and t for t and d found in this word. This vacillation becomes even more interesting if one explores the possibility that this letter was written via dictation by Lovise Korbi to a ghost writer. Such direct auditory processing would be even more likely to result in surface variation in the language’s orthography.

Tables 3, 4, and 5 give more examples of t/d substitution found in the Kven letters in different grammatical contexts. Table 3 shows substitution of t for d in the context of qualitative gradation, where the words in MWF would have d as the weak variant of t instead of the attested t, Table 4 gives examples in non-gradation contexts, and Table 5 in suffixal contexts.

Table 3. Substitution of t for d in qualitative gradation contexts

a The word pito only hypothetically exists in the nominative singular in the meaning ‘party’, and the plural form pidot is used instead. We give the nominative singular here for the sake of clarity.

b The full phrase in the original is muutamala ratilla, which would be rendered in MWF as muutamalla rivillä ‘with a few lines’.

c The word vedenhätä is a compound word, the first part veden being the genitive singular of vesi ‘water’. The first part of compound words in Finnish is sometimes in the genitive, sometimes in the nominative.

Table 4. Substitution of t for d in non-gradation contexts

Table 5. Substitution of t for d in suffixes

As Paunonen (Reference Paunonen, Sisko Brunni, Palviainen and Sivonen2018) notes, hypercorrection is only one explanation for the rendering of standard Finnish d as t. The dictionary of Meänkieli (Kenttä & Wande Reference Kenttä and Wande1992) includes a group of words containing t for the standard Finnish d, such as totistaa for todistaa ‘to witness’, muotostaa for muodostaa ‘to form’, and etulinen for edullinen ‘affordable, advantageous’, suggesting that t was the phoneme used in such words where Modern Written Finnish contains d. Paunonen goes on to suggest that the source of these t-containing variants could be religious in nature, pointing to the verb totistaa ‘to witness’ as an example. The Northern parts of Finland, Sweden, and Norway are all areas where the pietistic Lutheran revival movement Laestadianism was dominant, especially during the late nineteenth century. Lay preachers would often read Finnish religious texts and letters aloud to members of the congregation, and then preach based on them. The writings of Juhani Raattamaa (1811–1899) exhibit the same kind of inconsistent t∼d variation (Paunonen Reference Paunonen, Sisko Brunni, Palviainen and Sivonen2018) that we see in our corpus of Kven letters. In an excerpt from a letter dated 25 October 1875, Raattamaa renders the standard Finnish teidän (pron.2pl.gen) four different ways: three times as teitän, once as teidän, once as tejdän, and once as teidn (Raattamaa & Raittila Reference Raattamaa and Raittila1973).

A third source of explanation exists for the replacement of d with t. As noted earlier, d in Finnish exists primarily as the weak variant of t under consonant gradation. There are two types of consonant gradation in Finnish, quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative gradation involves geminate pp, tt, kk weakening to singleton p, t, k, while qualitative gradation involves singleton p and t leniting to v and d respectively, while k is elided completely. Quantitative gradation is a productive phenomenon in modern Finnish and occurs not only in words in the native vocabulary, but in loanwords and names as well, e.g. hitti ‘hit song’ vs. hitin (hit.song.gen)’ and Pekka ‘Peter’ vs. Pekan (Peter.gen). Qualitative gradation by contrast is not productive, and generally does not occur in loanwords and names. The genitive of the loanword auto ‘car’ is thus auton (not audon) and the genitive of the female name Lempi is Lempin (not Lemmin).

Not only is qualitative gradation no longer productive in Finnish, but there is also evidence that it has been losing its foothold in the native vocabulary as well. Qualitative gradation has slowly been decaying since the 1500s (Räisänen Reference Räisänen1991:109), and this is particularly the case with loanwords from Swedish (such as in the examples above from the Kven letters of kauppapuotissa for MWF kauppapuodissa (shop.ine) or ratilla for MWF raadilla (line.ade)). Western Finnish dialects are also more likely to contain words that fail to undergo qualitative gradation compared to Eastern Finnish dialects. However, our examples are all words that involve t/d; if this were part of a more general trend of the decay of qualitative consonant gradation, we would also expect to find cases of the other qualitative gradation alternations of p/v and k eliding to remain p and k, respectively. However, such cases are lacking in the Kven letters.

In the next section we see the opposite phenomenon occurring: substitution of d for t, as part of a more general pattern of substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k respectively, regardless of position within the word. While the word-medial t/d substitution discussed above is attested in letters of Finnish speakers both in Finland and abroad, the locus of explanation for the substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k discussed in the next section must lie elsewhere, namely via transfer from Norwegian or Northern Sámi.

4.2 Use of b, d, g for p, t, k

A total of eleven writers used b, d, g for standard Finnish p, t, k, as seen in the excerpt in Figure 4 by Emil Johansen, born 1888 in Kistrand, Norway:

Original:

Samūli Baūlaharjū

Oūlū

olen sanūt dietoja Neiti [nimi] Lakselv – ettæ on kæynyt Obettaja Oūlūsta Noin barri vūota aikaa – ja bytæn deitæ hyvæntahtoisesti Ilmoittamhan minūle dietoja Oūlūsta –

MWF:

Samuli Paulaharju

Oulu

Olen saanut tietoja neiti [nimi] Lakselvistä – että täällä on käynyt opettaja Oulusta noin pari vuotta sitten – ja pyydän teitä hyväntahtoisesti ilmoittamaan minulle tietoja Oulusta –

English:

Samuli Paulaharju

Oulu

I have heard from Miss [name] Lakselv – that a teacher has been here from Oulu around two years ago – and I ask you kindly to get some information for me from Oulu –

Figure 4. Letter written by Emil Johansen to Samuli Paulaharju, dated 7 July1929 (S75a).

Table 6 lists example words in this letter illustrating this divergence from Modern Written Finnish orthography. Word-initial consonants appear to be especially sensitive to this substitution.

Table 6. Use of b and d by Emil Johansen

Tables 7, 8, and 9 give additional examples of the substitution in word-initial, word-medial, and word-final contexts from individuals whose letters contain more than one instance of word-initial b, d, g in native Finnish words. These writers do not do this substitution across the board: at times their orthography matches the norms of MWF. In contrast to the word-medial substitution of t for d discussed in the previous section, substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k occurs regardless of word position.

Table 7. Word-initial substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k in native words

Table 8. Word-medial substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k in native words

Table 9. Word-final substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k in native words

Our research suggests two potential sources for the substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k: linguistic transfer from either Norwegian or North Sámi, or influence from OLF, the earlier form of written Finnish used in religious texts through the early nineteenth century. We believe the former is the most likely explanation for the phenomenon, and in order to understand why, it is first necessary to give some background on the phonemic inventories of both Finnish and Norwegian.

Native Finnish words only contain the voiceless plosive phonemes /p/, /t/, /k/ and lack the voiced plosives /b/ and /g/, while /d/ typically occurs as the weak variant of /t/, as discussed in the previous section. As for b and g, they occur only in recent loanwords such as banaani ‘banana’ and greippi ‘grapefruit’, and even in modern Finnish many speakers pronounce b and g in speech as [p] and [k] respectively, so that bussi ‘bus’ and pussi ‘bag’ are homophonous (Jarva Reference Jarva1997). The unexpected presence of the letters b, d, g in the Kven letters in our corpus thus requires explanation, as contemporary letter writers in Finland would have had little reason to substitute d for t, b for p, and g for k in their writing (although see Nordlund Reference Nordlund2013:119, which describes early nineteenth-century writers with similar examples to those seen here, such as deidän for teidän ‘your’ (pron.2pl.gen) and joda for jota ‘of which’ (which.par)).

In contrast to Finnish, the phonemic consonant inventory of Norwegian includes both voiced and voiceless plosives, /b/, /d/, /g/ and /p/, /t/, /k/, respectively. Importantly, the voiceless plosives in Norwegian surface as aspirated [ph], [th], [kh], especially in word-initial position (Kristoffersen Reference Kristoffersen2000:22). The feature of aspiration carries a strong functional load in word-initial position in Norwegian, as is also the case in most Germanic languages, since the voiced plosives /b/, /d/, /g/ normally surface as unaspirated, voiceless, or partially devoiced in this position (Kristoffersen Reference Kristoffersen2000:22). As such, in Norwegian the word-initial partially devoiced phonemes /b/, /d/, /g/, represented orthographically as b, d, g, would sound most similar to Finnish /p/, /t/, /k/ in this position since the voiceless stops in Finnish are always unaspirated. The occurrences of b, d, g in various positions in native words can be seen in Table 10. Loanwords and names containing b, d, g are excluded here, since the convention in Finnish orthography always has been to render such words faithfully with b, d, g.

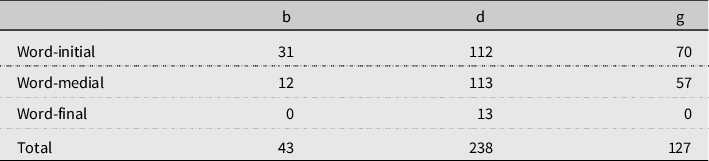

Table 10. Occurrences of b, d, g in various positions in native Finnish words

Only coronal sounds (t, n, l, r, s) are allowed word-finally in Finnish, which is why there are no instances of b and g word-finally. Although d can occur in Finnish as the weak variant of t and g can also occur in the combination ng as the weak variant of nk in qualitative consonant gradation word medially, as discussed previously, the word-medial occurrences of d and g in Table 10 correspond to instances of t and k in MWF, and thus are not related to consonant gradation.

Since five of the writers who used orthographic b, d, g in their letters were born in Norway, we can assume that they spoke Norwegian and potentially attended school, since primary schools were established in Norway much earlier than in Finland. Their use of b, d, g for standard Finnish p, t, k can thus be understood as arising from a kind of confusion between two phonemic consonant inventories: writers with little training in writing Finnish might naturally use b, d, g in writing Finnish since word-initial p in Finnish would sound most similar to word-initial b in Norwegian and very unlike word-initial p, which is aspirated.

Additional evidence for the confusion of b, d, g for Finnish p, t, k comes from the Norwegianization of many Finnish surnames. For example, Finnish Tikkanen became Dikkanen in Northern Norway, while Kantola became Gandola. If Finnish speakers really equated Finnish p, t, k to Norwegian p, t, k, there would be no need to change the spelling of such names, yet such respellings are widespread and common. Norwegian officials also often spelled Finnish surnames as they heard them, resulting in b, d, g in place of Finnish p, t, k (Alhaug & Saarelma Reference Alhaug and Saarelma2008:7). This same phenomenon occurred with Finnish surnames in the United States, for example Törmänen became Dormanen and Pernu became Bernu. As English is also a Germanic language and its voiceless and voiced plosives are essentially identical to those of Norwegian, the fact that this occurred independently in two different countries lends further support to this analysis.

The North Sámi language is another potential source for the use of b, d, g for standard Finnish p, t, k, since it utilizes orthographic b, d, g in native words (see Leem Reference Leem1748, Reference Leem1756; Rask Reference Rask1832; Stockfleth Reference Stockfleth1837, Reference Stockfleth1840, Reference Stockfleth1852; Friis Reference Friis1856, Reference Friis1887; Nielsen Reference Nielsen1932, among others, for the development of the North Sámi orthographic system), and orthographic b, d, g in Northern Sámi correspond to the voiceless plosives /p, t, k/ – the same phonemes represented as p, t, k in MWF (Valijärvi & Kahn Reference Valijärvi and Kahn2017:14–15). Northern Norway was and still is an area where three languages coexist: Norwegian, North Sámi, and Kven. We believe two of the Norwegian-born writers who use b, d, g to be Sámi: Elen Øvergård and Benjamin Josefsen (and/or his wife Inga Josefsen – both signed a postcard sent to Samuli Paulaharju). Elen Øvergård was born in Kautokeino, an overwhelmingly Sámi municipality in Finnmark, and Benjamin and Inga Josefesen are both described by Paulaharju (Reference Paulaharju1935) as being Sámi. We do not know whether any of them were literate in Sámi, but it is a distinct possibility.

Another potential reason for the use of b, d, g in place of p, t, k is influence from religious literature written in OLF or EMF, in which b, d, g were used more often than in MWF. In particular, b, d, g were used instead of p, t, k after the sonorant consonants m, n, l so that modern-day ylempänä ‘higher up’ was rendered as ylembänä, senkaltainen ‘of that kind’ as senkaldainen, and kuitenkin ‘however’ as kuitengin (Wilcox & Frosterus Reference Wilcox and Frosterus1779). Some loanwords were also written with b, d, g in place of modern-day p, t, k, such as duomita ‘to judge’ for the modern tuomita or basuna ‘trombone’ for pasuuna (Lauerma Reference Lauerma2012:31). Paulaharju (Reference Paulaharju1928:461) and Niiranen (Reference Niiranen2019:28) mention specific titles of religious texts that Kvens possessed, such as Kallihit hunajan pisarat (Honey out of the rock) by English Puritan Thomas Wilcox or Paratiisin yrttitarha (The garden of paradise) by German Lutheran theologian and early influencer on Pietist thought Johann Arndt. The writers who substituted b, d, g for p, t, k could possibly have been influenced by such texts written in OLF, since they were relatively isolated linguistically and would only have had access to religious texts in Finnish due to their lower socioeconomic status. However, as noted by Häkkinen (Reference Häkkinen1994:180), the orthography of MWF was already largely in place by the mid-1800s, with the sole exception of the letter w, which was used for modern v well past that date. If our writers, who were writing in the 1920s and 1930s, were really influenced by OLF, then they would have needed to have exposure to very, very old texts printed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Also, the distribution of b, d, g in OLF is restricted to post-sonorant environments, as discussed above, while the writers in our study used them in all positions in the word, and they especially used b, d, g in word-initial position, which lends credence to the phonological transfer from Norwegian argued for earlier. Word-initial b, d, g are absent from native words in the texts of Mikael Agricola, the creator of the first form of written Finnish in the sixteenth century (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen2015:82).

Given this preponderance of evidence, we attribute the use of b, d, g in the letters in our study to transfer from Norwegian or Northern Sámi. The Norwegian-born writers in our study were probably all literate in Norwegian (or potentially Northern Sámi), and the two Finnish-born ones likely arrived in Norway with little schooling under their belts and had a fair amount of exposure to Norwegian after their arrival. By contrast, the other Finnish-born writers in our study rarely if ever used b, d, g in place of p, t, k, and the remaining Norwegian-born writers were exposed to MWF due to their higher socioeconomic status and/or contacts with Finland. This exposure resulted in them writing in a way that is close to the MWF standard of the time.

4.3 Use of Norwegian characters

The use of Norwegian characters in the letters of some writers suggests that these writers were literate in Norwegian. A total of three writers substituted Norwegian æ for Finnish ä, letters which are pronounced by and large identically in both languages. The excerpt in Figure 5 is from a letter written by a woman born in 1904 in Kistrand, Norway:

Original:

Beronka, Tet hæ¨nen kyllæ Tūūnetta.

Minæ olen nyt kæyny Leminjoven kirkossa ja lóýsin Sūomalainen Biblia. Kirkossa Dæ¨læ¨ on nytt Paljon lünta

MWF:

Beronka, Te hänet kyllä tunnette.

Minä olen nyt käynyt Lemmijoen kirkossa, ja löysin suomalaisen Biblian. Täällä kirkolla on nyt paljon lunta

English:

Beronka, you definitely know him.

I have visited the church in Lakselv and found a Finnish Bible. There is a lot of snow here in town.

Figure 5. Letter written by a woman born 1904 in Kistrand, NO to Jenny Paulaharju, dated 11 February 1928 (J152b).

What is particularly striking about this excerpt is that not only did the writer use Norwegian æ for Finnish ä, she also sometimes put two dots above the æ as can be seen in the word dæ¨læ¨ for standard Finnish täällä ‘here’. Again, we can take this as direct evidence that the writer in question was literate in Norwegian. One writer (using a typewriter) also uses the Norwegian letter ø in place of Finnish ö (as in myøs for myös ‘also’) but paradoxically uses Finnish ä instead of Norwegian æ. One writer also renders Finnish ö as ó in cursive (e.g. in törmällä (hill.ade)), which is a convention of Norwegian cursive (Bolstad Reference Bolstad2021), not Finnish, where it would be rendered as ō.

Another orthographic character used by several letter writers is ū. An example written by Emil Johansen is given in Figure 6, where Oulusta (Oulu.ela) is written as Oūlūsta:

Original:

… Ilmoittamhan minūle dietoja Oūlūsta – ja ilmoitan deile – ettæ minūn Vanhimat ovat syndysin Oūlūsta – ja ovat tūlhet Norjan. on Noin 50 Vūota…

MWF:

… ilmoittamaan minulle tietoja Oulusta – ja ilmoitan teille – että minun vanhempani ovat syntyisin Oulusta, ja ovat tulleet Norjaan noin 50 vuotta …

English:

… relay some information to me from Oulu – and I will tell you that my parents are from Oulu and came to Norway about 50 years ago …

Figure 6. Letter written by Emil Johansen to Samuli Paulaharju, dated 7 July 1929 (S75a).

In one of the letters bearing the signature of Finnish-born Lovise Korbi, the oldest writer in our study, we find occurrences of ū. However, as discussed in Section 3.3 above, the letter in which ū appears was presumably written by someone else, likely Norwegian-born. The source of this character is the so-called Kurrent (or Gothic) cursive script which traces its origins to Germany (Pfändtner Reference Pfändtner, Coulson and Babcock2020). The function of the macron above the ū is to distinguish it from n in handwritten texts. The use of the Kurrent cursive script was still common in Norway in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Geelmuyden Reference Geelmuyden2015), but to our knowledge it was not still in use in Finland at this time. Similar to the substitution of æ for Finnish ä, the use of ū thus provides evidence that these writers were accustomed to writing in Norwegian, since none of the Finnish-born writers used this symbol in their handwriting.

5. Discussion

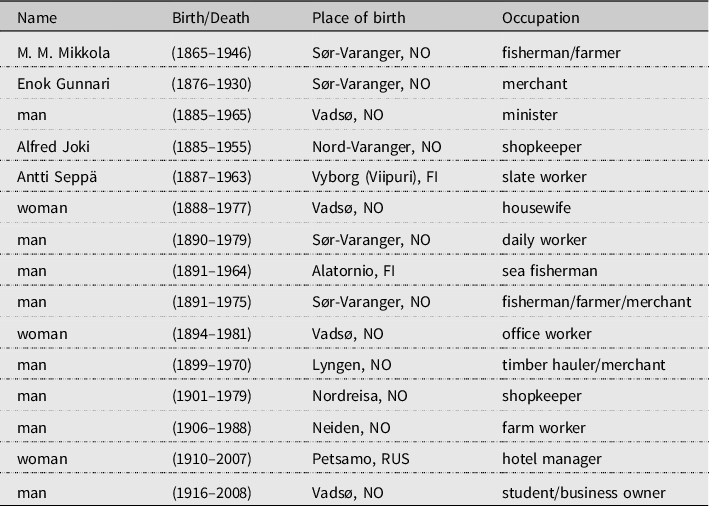

The writers of the Kven letters can be divided into two rough groups on the basis of whether or not they use b, d, g in a non-standard way. Those who use b, d, g in this way belong to an older literary culture and generally lack formal training in writing as well as access to texts in MWF. These Kven writers resemble the ordinary writers described by Lyons (Reference Lyons2012), who also lack much if any formal training. The use of b, d, g provides clear evidence of transfer from Norwegian (or Northern Sámi) due to their living in a multilingual environment. The second group consists of writers who write in a way that approaches MWF of the time. The other two orthographic phenomena we investigated, namely t/d substitution and use of Norwegian characters, are not confined to either group. Both groups of Kven writers in our study exhibit t/d substitution, as do Finns living in Finland during the same time period. The use of Norwegian characters similarly is not restricted to either group of writers. Table 11 includes biographical information on Kven writers who use b, d, g in place of p, t, k.

Table 11. Kven writers using b, d, g in a non-standard way

Of these eleven writers substituting b, d, g for p, t, k, eight were born in Norway and three in Finland. However, the three Finnish-born writers (Mathis Kumbula, Elmine Harila (see Appendix), and Job Pirttikangas) were all born at a time before primary schools had been widely established in the country. The first primary schools in Finland were established as a result of the primary school decree of 1866, but the process of building schools throughout the country was gradual, especially in Northern and Eastern Finland where it sometimes took many decades (Lassila Reference Lassila2001, Kauranen Reference Kauranen2013:27–28). Mathis Kumbula immigrated to Norway in 1865 at the age of 10, and we can thus be quite certain that he did not attend school in Finland. Elmine Harila immigrated to Norway in 1881 at the age of 18, and so potentially could have attended school in Finland, but the first primary school in her native Turtola did not open its doors until 1905 (Lassila Reference Lassila2001:591). Job Pirttikangas was born in 1860 and immigrated to Norway sometime in the 1880s. However, the single piece of writing from him is a short postcard sent from a nursing home, which could have been written by another person. Importantly, none of the other Finnish-born writers in our corpus engage in this substitution.

Given these Finnish-born writers’ lack of education in Finland, we claim that their writing was influenced by Norwegian. Mathis Kumbula was only ten years old when he arrived in Norway, so it is likely he acquired Norwegian from attending school or his local community. Among his professions are merchant and rural mail carrier, both of which suggest interaction with speakers of Norwegian. As for Elmine Harila, historical records indicate she worked as a domestic in a Norwegian-speaking household shortly after her arrival in Norway (DA; Beronka Reference Beronka1933:101), where she may have learned to speak some Norwegian and could also have been exposed to the written language. We do not know anything about any books or publications in Finnish either may have possessed, but our suspicion is that they were primarily religious in nature.

The eight Norwegian-born writers who use b, d, g belong to different generations: the three oldest were born between 1854 and 1863, while the other five were born between 1880 and 1904. We see clear transfer from Norwegian in the letters of Karl Methi and Erik Vinnelys, as Methi uses the Norwegian letter æ instead of the Finnish ä in his letters, and Vinnelys uses the Norwegian cursive letter ū in his writing, as discussed in Section 4.3 above. Of these writers, Vinnelys likely had more contact with religious literature in Finnish due to his occupation as a Laestadian minister, and we only see a few occurrences of b, d, g in his letters.

When comparing the Kven letters to letters written by other Finnish-speaking groups outside of Finland, we note a crucial difference in their writing. Letters written by Finnish Americans (such as in Sihvola Reference Sihvola2020, also Karvonen Reference Karvonen1916), for instance, contain far fewer occurrences of b, d, g compared to the Kven letters in our study. Both Kvens and Finnish Americans would have been influenced to some degree by the local languages Norwegian and English, and we might expect these languages to influence the writing of Kvens and Finnish Americans in a similar way, given the similarities between the phonological systems of Norwegian and English, especially with respect to plosives. Both Norwegian and English contain the voiceless plosives p, t, k, and in both languages they are aspirated word-initially. Both also include the voiced plosives b, d, g, and the partial devoicing of word-initial voiced plosives in Norwegian discussed in Section 4.2 applies to English as well. We would thus expect to find the same kinds of b, d, g substitution for p, t, k seen in the Kven letters in Finnish American letters, but that is not witnessed by the data.

However, there are at least two factors which we believe influenced how Kvens wrote compared to Finnish Americans. First, modern emigration from Finland to the United States in general occurred later, beginning with the first settlers arriving in Red Wing, Minnesota in 1864 (Alanen Reference Alanen2012:1). By contrast, immigration from Finland to Northern Norway began much earlier, examples of which can be seen in Table 11, where two of the Kven writers in our study were born in Norway already in the 1850s. The result of this difference is that Finnish immigrants (especially children) to the United States were more likely to have had some schooling in their home country.

A second reason lies in the differences in Finnish-language publishing in the two countries. A wide range of materials were published in Finnish in the United States, ranging from children’s books to socialist newspapers, and Finnish-language newspapers were especially popular and read widely by Finnish Americans (Kostiainen Reference Kostiainen and Kostiainen2014:205–206). Newspapers were also cheap compared to books. By contrast, only one Finnish-language newspaper existed in Northern Norway, and it was only published for a brief period (Paulaharju Reference Paulaharju1927:21–22, Ryymin Reference Ryymin2004:132–135). The likely reason for this paucity of Finnish-language publishing in Norway is the assimilationist policy of Norwegianization practiced by the Norwegian government, a policy which had no correlate in the United States. The language printed in newspapers thus acted as models for Finnish Americans, while most everyday Kvens possessed only religious texts in Finnish, and other kinds of books from Finland were reserved for those with adequate resources to purchase them.

Table 12 lists individuals who write approximating the MWF norm when writing the plosives p, t, k. They do not use b, d, g in word-initial position in native Finnish words. However, among these writers we also find some who frequently substitute t for d. These writers are M. M. Mikkola, Antti Seppä, and a woman born in 1894 in Vadsø.

Table 12. Writers using MWF

The writers in this group were born between 1865 and 1916. Many writers in this group differ from the first group because of their occupations. Among them we see several shopkeepers, some with higher education (a minister), and professions such as office worker or hotel manager. Such professions also require knowledge of Norwegian. Therefore, we hypothesize that many in this group possessed a high level of bilingualism, as historical records reveal that several are known to have been prominent members of their community. Their knowledge of written Norwegian is also visible in their letters via the use of Norwegian characters. However, this is sometimes due to the use of a typewriter.

In many cases, their knowledge of MWF can also be explained by their occupation. For example, some of the shopkeepers such as Enok Gunnari (see the Appendix) are known to have conducted a fair amount of trade with Finns (Eriksen & Niemi Reference Eriksen and Niemi1981:145). Another explanation is experience reading texts in MWF. Paulaharju also mentions that Enok Gunnari owned a large collection of books – not only religious books in Finnish but also books in Norwegian (Paulaharju Reference Paulaharju1928:205). Reading of other texts in addition to religious ones is significant for contact with MWF, as religious language did not develop as fast as secular literature during the time of EMF (Lauerma Reference Lauerma2013, Reference Lauerma2018). In this group we find many who ordered Finnish books or newspapers from Paulaharju in their letters. Several of them also typed their letters. Being able to buy books or order newspapers and having a typewriter indicates that these writers had more economic resources compared to other Kvens. For example, a man born in Lyngen in 1899 wrote that he had loaned Paulaharju’s Reference Paulaharju1928 book to many in his neighborhood, because it was too expensive for his neighbors to buy.

It is possible that writing in Norwegian – alongside reading in Finnish – was also used as a resource when writing Finnish. Some of the younger Norwegian-born MLF writers may have learned to read Finnish at school (see Section 2.2), or they may have acquired literacy in Finnish at home. Still, we do not have any precise information on how, for example, a man born in Lyngen in 1899 learned to write in modern Finnish, or how other MLF writers born in Norway learned to write MWF. Nonetheless, a man born in 1916 in Vadsø, Norway with no Kven background whatsoever learned to write MWF. He learned Finnish at Laestadian meetings and even achieved literacy – including good writing ability – in Finnish. He most certainly did not receive any formal instruction in Finnish due to his Norwegian family background. We conclude that most writers who sent letters to the Paulaharjus appear to be self-taught writers. Exceptions are those who previously learned to write in Finland at the end of the nineteenth century before moving to Norway.

Differences in orthography between the two groups of writers can be explained by the fact that literary texts, especially those written in MWF, were not accessible to all Kvens. The development of written Finnish was particularly associated with non-religious literature during the EMF period, and newspapers were a crucial tool for spreading the norms of MWF (e.g. Leino-Kaukiainen Reference Leino-Kaukiainen, Tommila and Pohls1989, Kokko Reference Kokko2021). Newspapers also played an important role among expatriate Finns, for example in spreading literacy in Finnish in the USA. Significant contact with MWF thus occurred via the reading of non-religious texts. However, many Kvens with religious convictions were not interested in reading non-religious literature but continued to read the religious texts they were familiar with (Paulaharju Reference Paulaharju1928:125, 522). Literature in MWF also was not available to Kvens in official libraries as it was in Finland (Luukkanen Reference Luukkanen2016). A catalogue from the library in Vadsø – a town with a large population of Kvens (see Section 2.2) – only mentions 17 titles in Finnish, most of them religious texts (Balke Reference Balke1925). This unequal exposure and access especially to MWF, along with geographical isolation and influence from the Norwegian and Sámi languages, explains the differences in orthography between these two groups of writers.

6. Conclusions

What emerges through the letters in our study is the presence of two different but at times overlapping writing cultures (see Lyons Reference Lyons2012). The first writing culture is influenced by OLF and EMF religious texts, particularly as connected to Laestadianism. The orthography used in letters written by the mostly older, often less educated writers belonging to this culture bears evidence of linguistic transfer from Norwegian and even Northern Sámi. The second writing culture is strongly tied to the linguistic developments in Finland associated with MWF. The writers exemplifying this culture are typically younger and have a higher socioeconomic status than those belonging to the older writing tradition. These writers obviously had access to texts (in a broad sense) written in standard Finnish as models, for example books and newspapers sent from Finland as well as letters written to them by Finns, since publications in Finnish were rarely if ever produced locally.

The second thread that emerges from our study is that all the writers were clearly writing in a multilingual environment. The letters were written while the writers were living in the counties of Troms and Finnmark in Northern Norway, an area where both then and now three different languages are spoken: Norwegian, Kven/Finnish, and Northern Sámi. Even though the writers in our study all wrote in Finnish, the vast majority of them would also have been proficient, if not fluent, in Norwegian as well. Several also spoke Northern Sámi.

Among the oldest, Finnish-born writers in our study, it is highly unlikely any of them received much, if any, schooling in Finland, since primary schools were not widely established until the late 1800s. Among the younger writers in our study, those few born in Finland likely attended primary school in Finland, while those born in Norway would have been taught in Norwegian, but still sometimes could have learned to read Finnish at school. Given that few of our writers likely received much education in Finnish, we suspect that most of them learned to write Finnish on their own (see Liljewall Reference Liljewall2013). General literacy in Finnish never spread completely among Kvens, one reason being the assimilationist policy of Norwegianization practiced by the Norwegian government. The isolation of Kvens from the linguistic developments in Finland forms the basis for why a new written language based on Kven dialects was developed in recent times.

This study concentrated on three orthographic phenomena in Kven letters: the substitution of b, d, g for p, t, k, the use of t for d, and the use of Norwegian characters. Many other topics remain for future research, not limited to but including the following: representation of short vs. long sounds, capitalization, rendering of compound words, use of archaic expressions, and presence of spoken language or dialect features in writing. As such, the Kven letters provide a rare window into how writers belonging to different generations and socioeconomic classes living in relative isolation in a multilingual environment negotiate writing in a language that for some is primarily oral, but for others is closely tied to the written word.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of the Nordic Journal of Linguistics for the many useful and constructive comments they provided which helped us narrow our focus and strengthen our arguments. We are especially indebted to the editors of this special edition of the journal for their extremely careful and thorough reading of our paper across multiple iterations: your attention to detail is greatly appreciated and unmatched.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Selected letters written to Samuli and Jenny Paulaharju

Elmine Harila, born 1863 in Turtola, Finland (Jenny 147a–d)

Vestrejacobselva

den 19 22/1 28

Nyd otan dilasuden ia aiattelen piirtä teile jongu rivin vaikka se olis pitäny tapahtua jo aigoia ennen van se on niin kuin olen niin hitas ia huono ja vielä vanhus haitta tähän dyöhön. Minun velvolisudeni olis ollu jo aikoia ennen deile kirjotta ia kiittää kaikkein kuvain etestä joita oleme saane kyllä oli meistä hauska lueskella ioulu lehteä

gyllä [nimi] tykkäsi kovasti kuin se sai joulu lehen niin kaukaa että oulusta ia go oli vielä miehen kuva ia kirjotus ja nyd saan muisdela että mie ia dyttäreni [nimi] olema tervenä ynä muut lapset ympäristöllä perheinsä kansa van mieheni ei ole kotonakkaan hällä duli doinen silmä niin huonogsi se gävi näitten läägäritten dygönä van kaikki durhan ei apua se paheni ia paheni päivä päivältä

Minä eppäilen ette saa selvä tästä sillä eise [?] juokse pännä vanhan gädessä

niin se sitte päätti lähdeä etemäksi se on yksi mies jota nimidetäna [nimi], se assu Finland näs se sanotan parantavan semmosiagi tautia jota ei kaikki läkärit parana niin se lähti gotoa 19 19/11 27 ia se tuli ensin tromsan se piti siittä lähteä pikku tampila siihen mihin hän meinasi se hänen piti siinä ototta kaksi päivä sen lähdöä. se siinä pakotettiin hänen käyvä niitten läägäritten dygönä ioita oli golme kaksi ensimäistä olit sanonu ette het ei voi mittään

sitte golmas se oli silmä läkäri se oli kattonu läpi ia sanonu ette se on paras että lähteä kristianian eli oslu Rishospidalin niin se menit turhan ja nin se oli lähteny sinne mihin hänen aikomuksensa oli ia se oli vain gysely ia gattonu ia andanu dropit ia saanu lähteä ia se on siittä menny sitte harstan jossa hällä on systerin lapsia ia net ei halva sitä lähtemän ennengä silmä on parempi ia net on kirjottanu ette se menne hyvästi etten gäsin /

ei ole göyhälä reisata semmosia matgoia ette oslun

Nyd aivon vähän muistela ette kalastusta täälä on ollu etelä joulun van ulos myyndi on ollu gerralista huononlainen hinta siis ei ole ihmisillä erinnommaista pärjäminen kuin kalastus on elingeinona tervenä elettän näilä seutuin ja kuolevaisus on harvinainen van on jo meän hautaus maasa kaheksantoista niin kuin olet tulitte tietämän että se on vasta saatu tähän paikkakuntan haudausmaa

Det muistatte sen talon jossa tet gävitte maistamassa kalla [nimi] net gäskevä tervehtä teitä ia vanha [nimi] myös. Ja meän lapset kaikin perheinen tervehtävät teitä. Sinne se elele seki jolla on kaheksan poika päivä menne ja toinen tulle tervenä ne on Nyt minun häty lopetta tullee liian pitkältä ia huonoa pittä olla kärsivälisyttä tätä lukgeissa kyllähän sitä muutengi teltä gysytän ko olette opettaiat. Nyt sanon hyvästin tällä gerta Voikat hyvin sydämeliset terveiset teile ynä herrane kansa

Toivotta

Elmine Harila

Enok Gunnari, born 1876 in Sør-Varanger (Samuli 6a)

Bygøyfjord den 30.11. 1928

Herra Opettaja ja kirjailia S.Paulaharju

Oulu

Arv. kirjeenne oheella sain pappavainaan valokuvan takasin josta kiitän.

Sanomalehdissä huomattuani kirjanne ilmestymisestä tilasin sen, ja luulen että moni Ruijan Suomalainen on tehnyt samoin.

Täällä tuli talvi aikaseen nimittäin lunta, vaan pakkasia on ollut vähän, nytkin parin viikon ajan vaan 3 a 5 astetta ja ihan tyyni ilma, jota meillä on harvoin tähän vuoden aikaan. Kun taas tullaan tammi ja helmikuulle, niin kyllä osanne myrskytä ja olla pakkanen.

Kalavuosi Ruijassa oli enemmän keskimääräinen, paitsi Varangin vuonon kalastus oli melko hyvä, ja sitä on jatkunut kesän ja syksyn, nytkin saataan Pykejän vesillä hyvin saitoja verkoilla. [Nimi] pyysi muuten sanomaan terveisiä, olin siellä hiljakkoin.

On hauskaa että meidän karut maisemat ja mahtavat kallioseinat viekoittelee ja muistuvat mieleen. Kuin nyt ensikerran tulette ruijaan, niin olette ystävänlisesti tervetulleita tänne Reisvuonoon myös.

Monet terveiset teille rouvanne kanssa vaimoltani ja allek.

Enok Gunnari [written by hand, the rest typewritten]