In 1802, Irish-born and London-trained pianist John Field (1782–1837) accompanied his teacher, Muzio Clementi, on a journey from London, travelling through Paris and Vienna before reaching their final destination of St Petersburg.Footnote 1 It was in Russia that Field would remain, becoming part of the active performance and teaching arenas of Moscow and St Petersburg, as well as taking up professional opportunities at aristocratic country residences. Significant changes in musical style mark Field's movement – notably, the youthful musical constraint that dominated much of his London-composed piano sonatas and sets of variations transitioned into freer-formed nocturnes, dance pieces and large-scale improvisatory works. Formal simplicity, extended pedalling technique and the flexible use of time characterize the nocturne, as further developed in the mid-nineteenth century by Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt and Mikhail Glinka.Footnote 2

Field's nocturnes serve as a useful means to consider facets of his stylistic evolution, including distance from the London pianoforte school and general artistic maturation. Here, however, I wish to focus on the impact of the change in landscape, offering a new understanding of Field's nocturne as a product of travel and place, which was marketed over the course of the nineteenth century as a Russia-based idiom. I offer an examination of Field's earliest nocturnes with the aim of peeling back a layer of time to reveal their locale, to strengthen the connection of place to his work's stylistic development and dissemination.

Understanding nineteenth-century music through a re-imagining of place is both challenging and productive, as demonstrated by Theodor Adorno's surreal envisioning of Schubert's landscape, Holly Watkins’ exploration of Schumann, place and placelessness, and Daniel Grimley's study of Grieg's environment and national identity.Footnote 3 As these examples indicate, traces of a composer's locale are undeniably held within musical works, but it is difficult to pinpoint the exact moments, views or experiences contained within a score. Marc Antrop notes that landscape can include subjective observation and experience, and consequently holds perceptive, aesthetic, artistic and existential significance.Footnote 4 Consequently, we can identify multiple layers of meaning when hearing or viewing a musical work and deepen our understanding of the composer's own time and place through their environment and experience.

Although little documentation remains of Field's Russian experiences as described in his own voice, we can imagine elements of the places in which he worked through musical publications, related contemporary descriptions and recollections of friends and admirers. These sources provide a more nuanced understanding of Field's early piano œuvre and shed fresh light on the shift in his musical style on relocation. Differences between the cities of Moscow and St Petersburg also provide a key ecological context, with the extreme northern latitude of St Petersburg (which sits on the 60th parallel north) creating long winter nights and pearl-coloured summer evenings near the solstices of the calendar year. It was this unique environment, as I explore here, that led Liszt to imagine Field's nocturnes as a Russian-created genre in his preface to Julius Schuberth's defining posthumous collected editions of the 1850s and 60s – a move that would play a crucial part in the nocturne's international dissemination.Footnote 5 Through this distribution we see how the nocturnes sparked imaginings of the Russian nightscape, and consequently how environment appealed to the nineteenth-century transnational music market.

Considering John Field's Geographic Place and National Identity

Questions of national belonging have always formed a significant part of narratives in Field scholarship, as is evident in Grattan Flood's summary:

To sum up, John Field of Dublin enjoys the triple distinction (1) of having been the Inventor of the Nocturne; (2) of having been an incomparable virtuoso on the pianoforte; and (3) of having been the teacher and friend of Glinka, the founder of the Russian School of Music. These three distinctions are more than sufficient to ensure for him a place among the immortals in Music. He inherited the musical traditions of the Irish School of Music so lauded by Giraldus Cambrensis, and worthily carried on by Garland, Power, Dowland, Campion, Costello, Purcell.Footnote 6

This succinct text defines Field by a variety of real, invented and imagined places – Dublin, the Russian School of Music, the Irish School of Music and a place among the ‘immortals in Music’ (a metaphorical position on Mount Parnassus). Association with the London piano school of composition is notably absent, although later Field scholarship acknowledges the link.Footnote 7 Flood's desire to position Field within a larger musical lineage interconnects geographic space with national school. This significance leads to questions regarding nationality and musical product in general and provokes a consideration of the environments inhabited through each location. Field scholar Patrick Piggott also defines John Field in a variety of national terms – a Francophile, a Bohemian and an Anglophobe.Footnote 8 Russian experts on Field, such as Aleksandr Nikolayev, have suggested a more general description of the composer as ‘English’, as instigated by nineteenth-century accounts such as the following by Louis Spohr, although this reflects Field's language abilities more than his national heritage or environment:

I have still in recollection the figure of the pale, overgrown youth, whom I have never since seen. When Field, who had outgrown his clothes, placed himself at the piano, stretched out his arms over the keyboard, so that the sleeves shrunk up nearly to his elbows, his whole figure appeared awkward and stiff in the highest degree; but as soon as his touching instrumentation began, everything else was forgotten, and one became all ear. Unhappily, I could not express my emotion and thankfulness to the young man otherwise than by a silent pressure of the hand, for he spoke no other language, but his mother tongue.Footnote 9

George Grove's original Dictionary of Music and Musicians meanwhile considered Field as ‘Russian’ and described his piano technique as ‘distinguished by the most smooth and equable touch, the most perfect legato, with supple wrists and quiet position of the hands’.Footnote 10 The Dictionary provides a partial history of Field's life and career with a curious mix of information, including an explanation of the nocturne's main characteristics:

FIELD, John, known as ‘Russian Field’ … Both as a player and as a composer Chopin, and with him all modern pianists, are much indebted to Field. The form of Chopin's weird nocturnes, the kind of emotion embodied therein, the type of melody and its graceful embellishments, the peculiar waving accompaniments in widespread chords, with their vaguely prolonged sound resting on the pedals, all this and more we owe to Field.Footnote 11

Labelling Field ‘Russian’ and then suggesting that he was the influence behind Chopin's ‘weird’, emotional, ‘peculiar’ and vague nocturnes indicated to readers that this genre stemmed from beyond the West – that Field's nocturne was reflective of a Russian environment with which those contemporary to Grove and his writers may not have been familiar.

Field's national identity and his connection to location were complex matters even during his lifetime, and earlier nineteenth-century publications identified the composer as coming from a handful of places – specifically from St Petersburg, from England or from Russia. Early experiences in Ireland and London influenced Field's style and work; however, at the height of his fame in Europe, audiences recognized the Russian character of his music and performances. One concert review of 1833 described his unique touch as ‘a bit Russian’, making the piano keys ‘vibrate like metal’ with each note resonating like it was ‘produced by a flute of crystal’.Footnote 12

Although Field lived and worked in Russia during most of his adult life, it is difficult to identify exactly where the inspiration for specific works took place. His frequent travel between Moscow and St Petersburg further complicates potential connections to place, as do issues surrounding the revisions of Field's final works during his European tours of the 1830s. For example, the title page to Schlesinger's 1833 Parisian edition of Le Midi carries the following description: Midi – Nocturne caractéristique, composé et executé à Paris par John Field de St. Petersbourg.Footnote 13 This wording raises questions in relation to Field's music and environment: What was the significance of Schlesinger listing Field as specifically coming from St Petersburg? Was there a specific market demand for work that had been (apparently) composed in Paris by a Russian artist? I consider these questions through the common element of place and imagined environment as connecting music to composer and audience.

English Sonatas to Russian Nocturnes

Examples of Field's London work supply a valuable baseline from which to measure the early nocturne's evolution. Following the vogue for importing continental musicians and their representative styles to London during the late eighteenth century, the city began to export its domestic musical products in the form of publications, instruments and, on occasion, musicians in the early 1800s.Footnote 14 Field was part of a newer generation of London-trained players who worked outside of the city's domestic music scene. Considered as part of the London piano school, Field studied and composed in the city from 1793–1801 and produced most of his mature work as a long-term visitor in Russia from 1802 until the 1830s. He remained a freelance musician throughout his career, unhindered by court obligations that could have significantly limited his ability to publish outside of the English market.

Field's position as Clementi's student shaped much of his own London experience; as a young pianist he appeared in concert alongside his teacher and published a handful of early works. Dedicated to Clementi and published in London in 1801, Field's Opus 1 sonatas (H8) reflect the influence of Clementi's rigid compositional approach while introducing some characteristics that would remain embedded in Field's later style.Footnote 15 The three H8 sonatas are in two-movement form, without slower-paced Adagio or Andante movements. Sonata Opus 1 No. 1 in E-flat major very much embodies the London pianoforte school style, with its repetitive bass patterns, driving passage work and expressive use of the English piano's shimmering upper range (Ex. 1). Notably, these musical traits foreshadow stylistic elements that mature more freely within Field's nocturne genre. Elements such as the adept manipulation of transparent texture and the use of fluid and extended upper melodic lines develop into prominent features of his Russian work of the 1810s and 1820s.

Ex. 1 John Field, Sonata in E-flat major, Op. 1 No. 1, H8, Allegro moderato (London: Clementi, 1801), bars 51–53.

The piano nocturne, as a genre, finds definition through the numerous examples, loose descriptions, and related works composed from the late eighteenth century onward – titles vary from ‘nocturne’ to ‘notturno’ and ‘Nachstück’. A type of work associated with ‘reveries of a soul’ (Gottfried Wilhelm Fink, 1834), ‘dreamy vagueness’ (Liszt, 1850) and ‘performed by night’ (Carl Czerny, 1834) does not lend itself well to the constraint of classification.Footnote 16 However, Field's piano nocturnes hold certain defining characteristics, some technical and some expressive. On the technical side, the Fieldian nocturne is a piano solo, single-movement miniature or character piece (often four to eight minutes in length), with static harmony, repetitive left-hand accompaniment that provides both rhythmic and tonal stability for a vocal-like right hand melody, virtuosic passages and detailed, sustained pedalling that catches low bass notes. In terms of expression and emotional character, Czerny noted that the piano nocturne ‘must be calculated to create an impression of a soft, fanciful, gracefully romantic, or even passionate kind, but never of a harsh or strange [kind]’.Footnote 17 The static harmonic nature of these works releases the player and listener from a desire to move forward from, or return to, a tonal centre – consequently the nocturne is a genre that might be defined through feeling, example and experience. The performer or listener's personal experience becomes a central element in understanding the nocturne from a fuller perspective, such as Field's time and place in early nineteenth-century Russia.

The nature of Field's early nocturnes – frequently revised and often found without a definitive autograph source – makes it difficult to determine an original composition date or location. He spent periods in St Petersburg, Moscow and aristocratic country residences during his initial post-London years; therefore, it is fitting to conflate descriptions and images of these places when imagining his early experience in Russia. Field maintained an apartment in Moscow until settling in St Petersburg more permanently by 1812, at which point Dalmas began to publish the early nocturnes that were likely composed as sketches in – or in between – both cities.

Late eighteenth-century London was a striking contrast to what Field later experienced in Russia. Nikolai Karamzin's Letters of a Russian Traveller (1789–90) provides an account of London's initial impact on a visitor, particularly at night with the strong presence of streetlights within the city:Footnote 18

there are thousands of street lights here, one after another, and wherever you look, there is everywhere a vista of flame, which from a distance looks like an endless fiery thread suspended in the air. I have never seen anything like it, and am not surprised by the mistake of a German prince, who, on arriving in London at night and seeing the bright illumination of the streets, thought that the city was illuminated for his arrival. The English nation loves lightFootnote 19

St Petersburg would have provided an especially stark contrast to London during the summer months, with its ‘white nights’ (belïye nochi) that blend dusk into dawn. Aleksandr Pushkin provides an evocative description in his narrative poem The Bronze Horseman: A St Petersburg Story:

Fyodor Dostoyevsky's short story White Nights: A Sentimental Story from the Diary of a Dreamer (1848) also includes descriptive passages of St Petersburg and the city's night sky on its opening page:

The sky was so starry, so bright that, looking at it, one could not help asking oneself whether ill-humoured and capricious people could live under such a sky.Footnote 21

The timelessness of St Petersburg's natural light is evident in contemporary imagery, such as Christian Hammer's early nineteenth-century topographical view of the city (Fig. 1).Footnote 22 The hand-coloured etching features a busy Saint Isaac Bridge – supported by large pontoons and rebuilt every summer – with pedestrians and carriages crossing the Neva. There are a handful of streetlights along the bridge's length, the Winter Palace and church clearly visible on the right, and the Admiralty tower seen at the centre of the etching. It is difficult to know what time of day the artist has depicted with long shadows and a dusk-like sky, but this is surely a summer scene with pedestrians in warm-weather attire, the Neva quiet and thawed, and the bridge fully constructed.

Fig. 1. Christian Gottlob Hammer, Vue du Pont d'Isaac, du Palais d'Hiver, de l'Admiralté etc. à St. Petersbourg (c. 1806)

Changes in season and place could have affected Field's nocturnal work habits, which are described by Louise Fusil in her diary Souvenirs d'une actrice (1841–46). Fusil was a French actor who lived in Moscow and was a close acquaintance of Field and his wife Adelaide Percheron. In her memoir, Fusil notes that:

Fild [sic] only worked when a concert date approached (he never played anything but his own music); but he had to be encouraged by his friends for a long time before deciding to sit down at the piano and work. … He was no longer a lazy man, he was the artist, the inspired composer; he wrote and threw papers to the ground, like the sybil's oracles, which his friends collected and put in order. One had to be knowledgeable to decipher his writings, as they were but scarcely formed ideas, but his friends were used to this. As he progressed in his work, his genius took over to such an extent that his copyists could barely follow him. … At three or four o'clock in the morning he would collapse, exhausted, onto the divan and sleep.Footnote 23

Field's work habits also reflected a greater sense of freedom that permeated his life. In Russia, Field was free from Clementi's professional constraints, and he was immensely popular with patrons and students, giving him the financial and social stability needed for an unfettered artistic life. Field's experience in Moscow also embraced the wealth of objects and materials available in the city as a rich commercial meeting point. Fusil vividly describes Field's Moscow apartment, a space filled with collections of miscellaneous items, gifts from admirers and his piano:

A large room, surrounded by low sofas and piles of cushions, as we find in most homes in Russia, served Fild's [sic] indolent laziness wonderfully, and made him look like a Pacha when he smoked a long pipe made of sandalwood while wrapped in his fur-lined dressing gown; kept beside him was a small table with a tray, bottles of rum and a small stove to warm wine. The walls were lined with cigar holders, pipes from every country in every shape, small Turkish tobacco bags in cashmere, cigars from Havana … Yatagans, daggers from Damascus adorned with precious stones; iron and gold objects from Toula; all presents, given to him by admirers of his talent, scattered about the room. A large round table covered with music, writing cases, and feather pens thrown in picturesque disorder; chairs scattered against the walls; four windows without curtains, and for his friends a beautiful piano, such was the furnishing of this Pacha of a new order.Footnote 24

Fusil's mention of ‘windows without curtains’ is particularly evocative; such an arrangement would have allowed Field to frame a cityscape, or even night's darkness, within the window of his apartment. The window frame also functions conceptually, imposing a limitation on the view and allowing Field to authenticate his experience while seated at the piano during his early period of experimentation away from London. The significance of such a window and its frame is not unique in nineteenth-century pianism – Beethoven's final Viennese apartment provides arguably the most famous example of a piano-room with a window as a cityscape frame.Footnote 25 Three days after Beethoven's death, visual artist Johann Nepomuk Hoechle visited the composer's home and captured his living quarters in a sketch.Footnote 26 Hoechle's drawing depicts the view from Beethoven's deathbed, focusing on his piano in the centre of the space, which looks out onto a moonlit Vienna. The image sold as an etched print during the nineteenth century, creating a lasting (and idealized) remembrance of Beethoven's view from the creative standpoint of his piano. In this case, the window functions as a memorial more than as a living representation. In Field's case, the literary idea of his curtainless windows, as described by Fusil, prompts an examination of his contemporaneous circumstances, including posing important questions relating to environment: what did he see in Moscow, and what type of cityscape did he experience there?

One method for experiencing Field's sense of place is contemporary visual representations of Moscow. Imagery that evokes cityscapes by night can provide Field's listener with their own view of his time in Russia. To this end, the work of Russian painter Fyodor Alekseyev (c. 1753–1824) is particularly useful. His vedute (highly detailed paintings and prints of cityscapes and other vistas) include meticulous depictions of Moscow, St Petersburg and various Russian locations, with an emphasis on architectural detail and street scenes. Alekseyev depicts a dramatic Moscovian nightscape in his Illumination in Sobornaya Square in Honour of Emperor Alexander I's Coronation, painted around the year of Field's arrival in Russia (c. 1802; Fig. 2).Footnote 27 Illumination in Sobornaya Square is a striking display of the celebrations in the city's main square captured, unusually, at night. Alekseyev recognizes natural light alongside the lanterns of the celebratory display. Above the hundreds of lights decorating the cathedral, with gold domes glowing in reflection and fireworks jumping from the bell tower, Alekseyev depicts a full moon breaking through the cloudy night's sky. The moon's central placement within the frame makes it the focal, and natural, element of illumination within the painting. The predominance of the night's natural strength is striking, functioning as a ‘nocturne’ itself (which, in non-musical terms, can be simply something that occurs at night). Surely similar evenings, albeit devoid of imperial glamour, would have been part of Field's Moscow during his years in residence.

Fig. 2 Fyodor Alekseyev, Illumination in Sobornaya Square in Honour of Emperor Alexander I's Coronation (c. 1802)

Early nineteenth-century Moscow provided an active environment that writers described as both European and Asiatic. Market days were particularly active, as described by Georg Reinbeck in 1805:

Loud crying of the hawkers; the singing of the izvoshchiks; the shouting inside and in front of the countless kabaks; the fiddling and piping and organ-grinding on the dance floors; the rattling of the carriages; the pealing of the thousands of bells, of which every single belfry has several, often twenty; interspersed with the drums and music of the considerable garrison.Footnote 28

The hundreds of bells noted by Reinbeck point to the enormous number of churches present throughout the city, with their onion domes and belfries punctuating each neighbourhood. The nightly cityscape would have varied immensely depending on the time of year, with streetlighting still at a minimal level during the early nineteenth century. Field's own window would have shown a predominantly dark cityscape during most of the year's evenings – when he would have played for his friends at the piano.

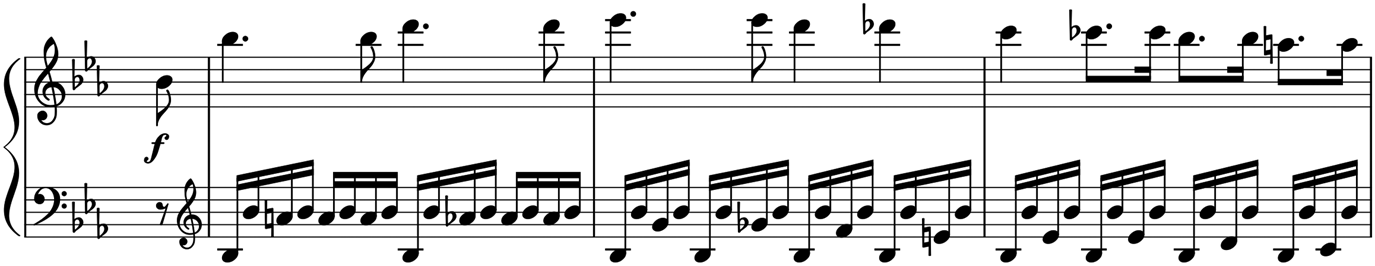

Fusil's description of Field's Moscow apartment also draws our attention to his collection of local objects and practices; this, too, seems to be present in his early Russian-composed piano work. In 1809, C.F. Schildbach published Field's virtuosic set of variations on an ‘air russe’ entitled Kamarinskaya (H22) in Moscow.Footnote 29 Kamarinskaya is stylistically different from both Field's London output and from his initial nocturnes, and thus serves as a pivot point in Field's stylistic development. The variations are based on the traditional dance kamarinskaya, a naigrïsh or quick tempo dance-tune built from a three-bar phrase played in endless variation.Footnote 30 This type of music often accompanied the kazatsky, a squatting dance. Field's Kamarinskaya uses a three-bar sequence and employs various jumping figures. The variations become increasingly difficult and include one-and-a-half-octave jumps outward in both hands, covering much of the piano keyboard in a series of individual gestures (Ex. 2). The extreme nature of this virtuosic writing captures Field's impressive technical capacity as well as mimicking the physically demanding nature of the original dance. However, it is the absence of harmonic movement that is particularly significant. The static nature of the tonal structure – which remains in B-flat major and plays between tonic and dominant harmony – would become a major feature of Field's early nocturne style. A lack of frequent modulation and the prolonged use of single harmonic chords echo the drone-like character of folk idioms. This method of creating a longer duration work independent from strict harmonic movement is a major stylistic contrast from sonata formal practice of the late eighteenth century.

Ex. 2 John Field, Kamarinskaya, Air russe favouri varié pour piano, H22 (Moscow: Schildbach, 1809), bars 91–101.

Works like Kamarinksaya did not inspire change alone. Another important consideration is the extensive time Field spent travelling between urban centres. As Piggott notes, Field taught in a variety of locations and could have done so ‘all day and every day’ if he wished.Footnote 31 Field's reputation as a virtuoso garnered a collection of patrons and students with both city residences and country houses, thereby affording him the opportunity to observe a variety of environments through the Russian cityscapes and countryside. The impact of prolonged and frequent travel has been seldom explored in relation to Field's compositional style but offers a key context for his post-London work. In particular, such travel was not part of Field's formative years in England, during which time the majority of his work and education took place within London. The carriage roads between Moscow and St Petersburg would have provided a notable opportunity for the pianist to experience Russia and its landscape outside of the urban émigré communities in which generally he lived and worked.

One cannot imagine early nineteenth-century carriage roads as fixed paths that were separate from the surrounding countryside. Rather, the road and the landscape were one and the same. Villages that serviced the carriage roads signalled a general direction of travel, particularly along the postal route fixed between large urban centres. These coach communities provided fresh horses and services for passengers to rest and allowed the postal system to function over a difficult and vast terrain. Historian John Randolph has attempted to envision the Moscow–St Petersburg corridor and landscape of the early 1800s by employing postal maps from 1808 to demonstrate distances between coach communities. As he notes, travel on the road did not just constitute a point-to-point journey on a narrowly defined pathway – rather, the road signified a journey through the extensive social world fashioned to support it. In this sense, the road represented an entire landscape, and for some coach communities, it embodied an entire world.Footnote 32

Aleksandr Radishchev's Journey from St Petersburg to Moscow (1790) provides an evocative account of travel on the carriage road in the decades before Field's Russian sojourn. Significantly, Radishchev's portrayal of the road and its coach communities includes mention of coachmen's music:

The horses hurry me along. My coachman has launched into song, a mournful one, as usual. Anyone who knows the melodies of Russian folk songs will admit that they contain something that expresses spiritual anguish of the soul. Practically all the melodies of songs of this kind have a soft tone.Footnote 33

One of the defining features of Field's piano nocturne is the slow rhythmic drone created by broken chords, a kind of ostinato in the bass or left hand. Field's use of ostinato emphasizes a lack of fast harmonic progression, a feature also found in his fast-tempo Kamarinskaya. The resulting constant sense of a pulse allows the nocturne's melodic line – placed in the upper register and right hand – to take on a remarkable amount of flexibility, creating a distinctive cantilena style of melodic treatment (Ex. 3). Rather than simply modifying a technique picked up from his Kamarinskaya setting, therefore, this texture – the pervasively repeating, rolling broken chords against a loose, expressive melody – might well evoke the perpetual movement of the carriage in counterpoint with the song of the coachman.

Ex. 3 John Field, Premier nocturne, H24 (St Petersburg: Dalmas, 1812), bars 1–17.

Field's use of a simple bass pattern thus provides a rhythmic palette that is open to manipulation in performance through techniques including pedalling, finger legato and expressive note placement. These techniques enable an exaggerated manipulation of time, which indicates a need for expressivity seldom captured in published scores of the previous century. Such gestures demonstrate how Field combined elements from his Russian experience (both sonic and visual) into an innovative and personal style, his nocturne genre loosened from the rigidity of classical form and proportion. Even the earliest of Field's nocturnes focus on expression and fluid technique, which demands a transparent and refined ability from the pianist as admired by audiences over the span of Field's performance career and posthumously through publication.

This expressive focus is evident even from the first St Petersburg publications of the nocturnes. As noted above, St Petersburg-based publisher Dalmas was an important proponent of Field's early work from 1812 on. Dalmas published Field's first three nocturnes (H24–26), his first two Divertissements (H13–14), various Fantaisies, dances and an exercise method.Footnote 34 The Dalmas edition of nocturnes H24 and H25 (1812) provides a large amount of expressive information within the notation. Intricately engraved, the scores include an abundance of dynamic markings, affective terms and pedalling denotation. Such detail within miniature pieces of only two to three pages in length is notable, and encourages a precise type of dialogue among composer, performer and listener. The score communicates a complete performance guide and generates specific emotions through Field's affective instructions. For instance, Field's first nocturne, H24 in E-flat major, has dynamic markings that range from pianissimo to forte, extended crescendos and meticulously defined pedalling.

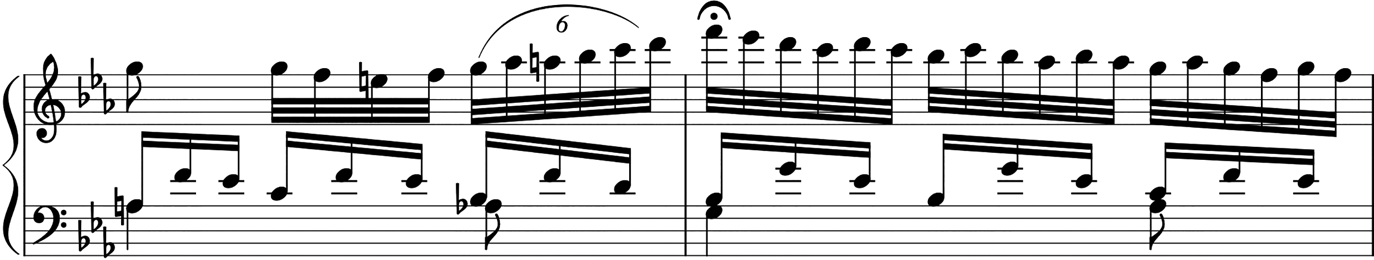

The second nocturne – also published by Dalmas in 1812 – is marked Moderato e molto espressivo and displays all the characteristics associated with the nocturne genre: a simple form, lack of modulation, highly developed and defined pedalling, and passages of improvisatory decoration. The melodic treatment, with its extended range and smooth leaps, is coloured with gentle moments of descending thirds. An outstanding feature in this nocturne is the extended passage of upper-note repetitions and leaps in the right hand, placed high in the piano's range (Ex. 4). The effect created by this repetitive figure moves beyond an evocation of the human voice and reflects an adaptation of the characteristically London-school compositional technique of playing within the high (undamped) register of the piano. The use of upper-note figures set alongside a low register bass pattern also evokes a broad sense of time and embodies a vast and still space.

Ex. 4 John Field, Second nocturne, H25 (St Petersburg: Dalmas, 1812), bars 77–92.

Publication and the Transnational Marketplace

Field's period in St Petersburg also signalled a professional transition – his first decade in Russia focused on building his reputation within St Petersburg and Moscow, but he began to gain recognition in Germany and France following the popularity of his nocturnes in the 1810s. The early Dalmas publications quickly circulated beyond the domestic Russian market, and in July 1815, Field received an offer to publish his existing works through Breitkopf & Härtel. He accepted with the stipulation that 18 months lapse between publication in Germany and sales in St Petersburg. Field commented on the sale of his work to a local publisher in a letter to Breitkopf in 1815:

I no longer possess my other works, as I have already sold them to the publisher here; this stops me from sending what you request, but it should be easy for you to find what you are missing through one of your contacts: all is already engraved.Footnote 35

Breitkopf released an edition of Field's first two nocturnes (H24–25) later in 1815 with the miniatures renamed ‘romances’. Branding the nocturnes as romances raises questions concerning the publisher's motivations in terms of marketing and suggests that the term ‘nocturne’ may have been less amenable to a new audience. It is likely that Field's local audience in St Petersburg was familiar with his nocturnes through his live performances, but a new audience outside of Russia would be more at ease with the general term romance. Indeed, this indicates the deliberate removal of a specified time and place to encourage successful sales; later in the century, as we will see, quite the opposite approach was taken. It is also possible that renaming the pieces romances helped to avoid conflict between Field's two publishers, as the change in genre created a contrast between the Russian and German editions.

There are numerous small discrepancies between the Dalmas and Breikopf editions, which further establish a moderate dissimilarity between the two versions. By contrast with that of Dalmas, Breitkopf's edition, entitled Trois Romances pour le Pianoforte par John Field, includes little detail, and H24 and H25 became Romance 2 and Romance 3.Footnote 36 The stark edition does not contain expressive markings, tempo, dynamics, articulation or pedalling (Ex. 5). In addition, the composer revised both H24 and H25 with considerable variation and extension. H25 develops into a significantly more substantial piece with rhythmic variation, changes in ornamentation and several extended passages (Ex. 6). The revisions are not surprising within the greater context of Field's œuvre, as he frequently revisited versions of his work as part of an ongoing compositional process. The three years between the St Petersburg edition in 1812 and the German edition in 1815 could have seen several iterations of the early nocturnes in Field's own performance life and teaching. He went on to revise H24 further in 1831, which demonstrates that a continual and long-term adaptation of work was not unusual.Footnote 37 However, the lack of expressive markings within the Breitkopf score is striking and demonstrates a different editorial approach between publishers and piano music markets early in the nocturne's dissemination.

Ex. 5 John Field, Romance 2, H24 (Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1815), bars 1–14.

Ex. 6 John Field, Romance 3, H25 (Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1815), bars 77–78.

Although Field's nocturnes circulated in small publications during his lifetime, collected editions of the works only appeared posthumously. Julius Schuberth (1804–75) published an initial collection in Hamburg in 1850, edited by Liszt. Entitled Six nocturnes pour le pianoforte, subsequent editions gradually added pieces to the group and rebranded pastorals and romances as nocturnes to fit the genre. Schuberth's edition appears to be based on the early Russian Dalmas publications, as it bears closer similarity to these copies than to the later editions by Breitkopf or other editions that circulated in the first half of the nineteenth century. Although there are small discrepancies between the Dalmas and Schuberth versions, the later edition maintains many of the expressive details, such as pedal markings, dynamics and affective specifications. Editorial differences found posthumously are not surprising as a general practice; however, combined with Field's numerous revisions of the nocturnes during his lifetime, editorial variance suggests that the score was ever evolving for its marketplace. A prefatory text provided by Liszt indicates that, at the same time, the score's ability to transmit the composer's original environment offered a particular appeal.

Liszt's florid preface for Schuberth's editions described the scenes and emotions he felt Field's music evoked.Footnote 38 The preface also appeared separately as a small booklet entitled Über John Field's Nocturne von Franz Liszt, with the original French text provided along with a German translation. This separate publication made the text available for purchase without the nocturne piano scores, which may have been attractive to a wider market, including non-musicians and purchasers who already owned copies of the nocturnes.

Liszt concertized in Russia during the springs of 1842 and 1843, and thus had first-hand experience of St Petersburg's vibrant night culture. Having spent time in the city in May, he would have seen the beginnings of the city's distinctive long days, if not its full white nights. Consequently, the composer's preface is a product of envisioned recollection and musical encounter, and describes the nocturnes as ‘musical pictures’ of imagined white nights in St Petersburg:

Is not that the dream of one who lies half-awake in a summer night without darkness, such as Field often saw in Russia? – a night whose veil is so pellucid as scarcely to obscure any objects … for the dreamy vagueness of the musical picture makes us feel that it was so painted only in the composer's imagination, not in accordance with any existing reality.Footnote 39

By referring to these musical images as recalled and imagined, Liszt could draw evocative lines between Field and Russia as a conjured place. He further emphasizes the connection of landscape to the musical experience of ‘nocturne’ through specific examples – the second nocturne (H25) is described as having ‘tints … like those of moonlight broken on a shady walk’ and being designed for one to feel the ‘absence from a world without sunlight’; the third and sixth nocturnes’ melodies (H26 and H40) are described as reflections of a sky that ‘colours the vapours of dawn, from pink, to blue, to lilac’.

The specificity of these images ties Liszt's own memories of Russia to Field's assumed expression and experience of landscape. This use of landscape is rich and varied – it embodies sound, an idea of place and a visual scene – and provides a venue for the listener to imagine a Russian night, even to undergo travel through music. The comparison of the nocturnes with moments of natural beauty emphasizes a connection between the concrete physical experience of a place and the musical experience of the nocturne. Liszt thus provides a key through which the listener can take part in a distant and imaginative journey, connecting them to the composer's own experience of a place and locale with which many would have been unfamiliar. Lev Tolstoy also describes such an encounter in the semi-biographical novel Childhood (1852):

Mamma was playing the Second Concerto of Field – her teacher. I dreamed that light, bright, transparent recollections penetrated my imagination.Footnote 40

It is likely that the character's imagined experience of ‘recollections’ in response to hearing music referred to the Andante movement from Field's second concerto. Often performed as a separate work (H31), this inner movement appears as a nocturne in later publications and circulated in Russia in a variety of versions and forms during the first half of the nineteenth century. Charles Elbert also published an early version of the work as a Sérénade in Moscow (1811), which predates the first Dalmas nocturne publication in St Petersburg (1812).

The Schuberth-Liszt edition grew to include 18 ‘nocturnes’ by 1859. The addition of pieces reflected the continued popularity of Field's nocturnes in Germany and abroad, with the publications’ circulation including markets as distant as North America. Schuberth's involvement was a major factor in disseminating Field's work, as his company released thousands of scores by the 1870s and had a branch in New York.Footnote 41 His Field editions retained Liszt's preface, often in multiple translations depending on location, indicating its ongoing appeal. Other publishers and editors released numerous posthumous editions of Field's nocturnes during the late nineteenth century – examples include Heugel et Cie’s publication of the first three nocturnes in Paris (1855), an edited version of the first nocturne released by Chappell & Co. in London (1859) and a collected edition by Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig (1882).Footnote 42 However, these editions did not offer the same personal experience provided through Liszt's text, or its level of understanding communicated through the explanation of Field's life and work in Russia. Chopin's work within the genre overshadowed the Fieldian nocturne over the course of the nineteenth century and a general understanding of Field's deep connection to his adopted home and musical culture was gradually obscured. Nonetheless, the recognition of his work's locale and his artistic process continues to offer a refreshed view of Field's stylistic development.

In many ways Field was part of a larger Russian artistic movement that broke formal conventions and expectations over the nineteenth century. Significantly, early nineteenth-century St Petersburg produced artists who founded major schools of Russian art – Field as a precursor to the Russian school of composition unhindered by previous formal conventions, and Pushkin as a founder of modern Russian literature. The Bronze Horseman, quoted previously, embodies this position of change, with sections written as eighteenth-century ode, embodying mythologized history, natural symbolism and pathos. Field's music holds similar emotions and experiences, although sound's ephemeral nature makes exact instances of emotion or place difficult to define.

Field's work developed over the course of his lifetime – and posthumously – in connection with travel, place and distribution. After he left London, he was able to develop a compositional style that was individualistic and free from rigid form. The piano nocturne – particularly the earliest examples of the genre – maintained some characteristics of the London-based school. However, these characteristics absorbed new influences and developed into a specific voice while Field lived and worked in St Petersburg and Moscow. The lack of rigidity in Field's Russian environment – including natural landscape, varied cityscape, prolonged travel and dreamy white nights – combined well with a social circle that supported and understood the pianist's work. As a result, the Field nocturne was a product of his time and place; but above all, it was remnants of place as imagined by later musicians and writers that enabled the nocturne's marketing success abroad as a Russian-created genre.