No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

The Text of Matthew 5.11

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1986

References

Notes

[1] Those favouring omission include Allen, W. C., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to S. Matthew, 3rd ed. (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1912) 43Google Scholar; McNeile, A. H., The Gospel according to St. Matthew (London: Macmillan, 1915) 53Google Scholar; Fenton, J. C., The Gospel of St. Matthew (Baltimore: Penguin, 1964) 83Google Scholar; Zahn, T., Das Evangelium des Matthäus, 4th ed. (Leipzig, 1922) 193Google Scholar; von Soden, H., Die Schriften des Neuen Testaments in ihrer ältesten erreichbaren Textgestalt, 2nd ed. (Berlin, 1911–13)Google Scholar, ad loc.; and most recently and significantly, Greeven, H. in Huck, A., Synopsis of the First Three Gospels, 13th ed., fundamentally revised by Greeven, H. (Tübingen, 1981) 31.Google Scholar

The word in question is included by, among others, Westcott, B. F. and Hort, F. J. A., The New Testament in the Original Greek (Cambridge, 1881)Google Scholar; Souter, A., Novum Testamentum Graece, 2nd ed. (Oxford, 1947)Google Scholar; Lagrange, M.-J., L'Évangile selon Saint Matthieu, 8th ed. (Paris: Gabalda, 1948) 87Google Scholar; Manson, T. W., The Sayings of Jesus (London: SCM, 1949) 48Google Scholar; Conzelmann, H., ‘Ψεος’, TDNT 9:601 n. 68Google Scholar; Plummer, A., The Gospel According to St. Matthew, 2nd ed. (London, 1910) 71Google Scholar; Filson, F. V., The Gospel According to St. Matthew (New York: Harper, 1960) 79Google Scholar; Hill, D., The Gospel of Matthew (London: Oliphants, 1972) 114Google Scholar; Weiss, Bernhard, Textkritik der Vier Evangelien (Leipzig, 1899) 151Google Scholar; Dupont, J.; Les Beatitudes, 2nd ed. (Louvain, 1958) 1:236–8Google Scholar; Gundry, R. H., Matthew: A Commentary on His Literary and Theological Art (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982) 74.Google Scholar

[2] Bruce Metzger, M., A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (London and New York: United Bible Societies, 1971) 12–13.Google Scholar

[3] Weiss, B. (Textkritik, 151Google Scholar) and Zahn, (Matthäus, 193Google Scholar) are notable but only partial exceptions.

[4] NA26 provides data for a total of seven variants in v 11. One of these, however, - δıωξωσω] δıωξουσıν א (D) W Δ Θ f13pc-‘natürlich reiner Schreibfehler ist’ (Weiss, B., Textkritik, 67Google Scholar), and has no value for determining textual relationships. The utility of a second variant (the transposition of ονεıδıσωσıν and δıωξωσıν by D 33 h k syc mae bo) is also suspect. The similar-sounding words could easily have been unconsciously interchanged during the copying process, or, as McNeile suspects (Matthew, 53), the change may be a harmonization to Luke 6. 22. If one should include this latter variant in an (analysis of 5. 11, it would 1) further support (the close connection observed between D, h, and k; and 2) place the reading of mae in the category of a ‘mixed’ text.

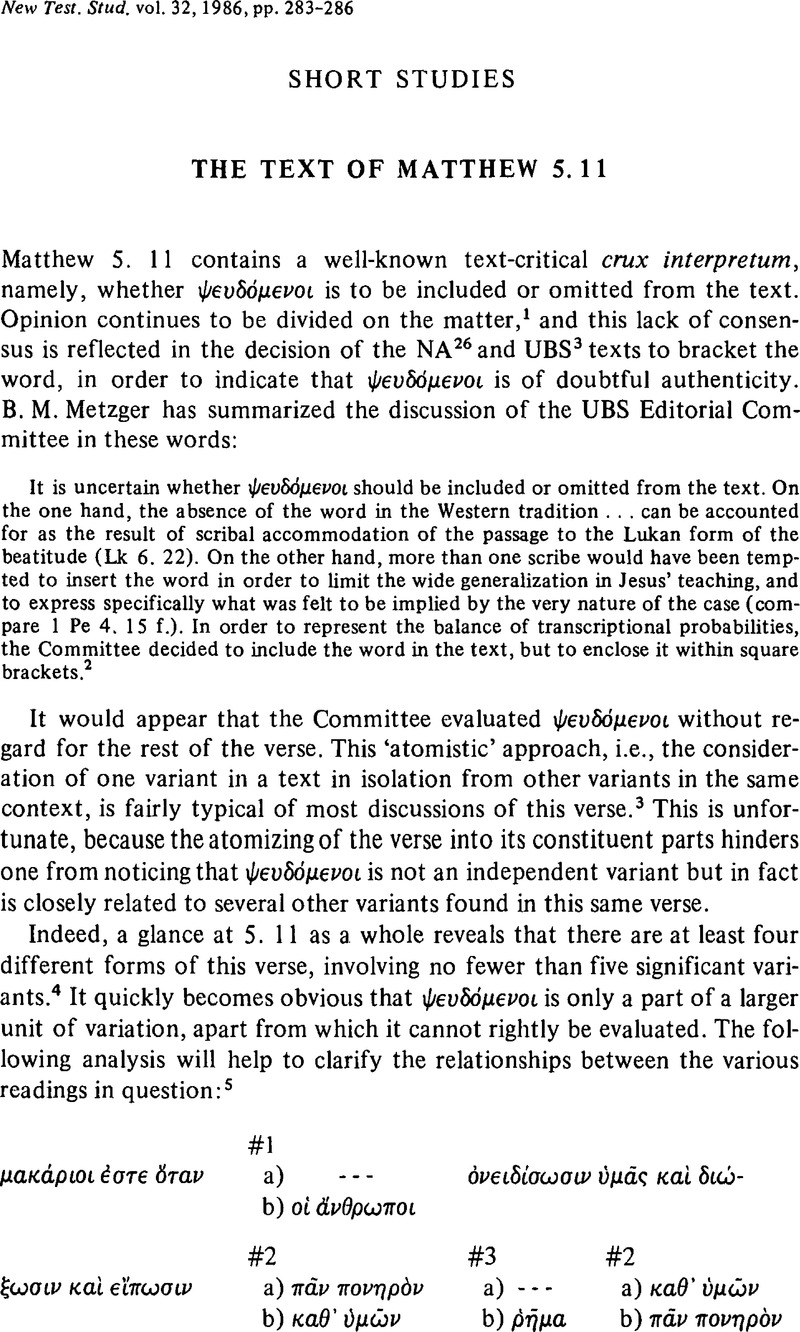

[5] The following textual evidence and symbols are those of NA26, with the exception that ‘Maj’ is used (instead of the Gothic capital M) as a symbol for the ‘Byzantine’ or ‘Majority’ group of manuscripts.

[6] The Old Syriac readings deserve notice. The double harmonization to Lucan passages (add οı ανθρωποı with 6. 22, and substitute του ονοματος μου with 21. 12) clearly links together syS and syC. Yet there are some notable differences. SyC shares with D the transposition of ονεıδıσωσıν and δıωξωσıν (see note 4 above), yet it has ψενδομενοı; syS omits the latter with D but does not follow D in the former. Interestingly enough, neither follows D in transposing παν πονηρον and καθ' υμων. This passage is in some ways paradigmatic of the complex and confusing situation one encounters in the Old Syriac manuscripts.

[7] Lohmeyer, E., Das Evangelium des Matthäus, ed. by Schmauch, W., 4th ed. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1967) 95Google Scholar; Zahn, (Matthäus, 193Google Scholar) describes it as ‘entbehrliche’. Both external and internal considerations support the view that ῤημα is a later gloss or addition: the text form lacking this word both has better early good manuscript support (‘Alexandrian’ and ‘Western’ versus ‘Byzantine’) and best explains the other variant. If ῤημα were original, it is difficult to posit a convincing reason for its omission, while its addition due to the influence of the preceding εıπωσıν is quite understandable.

[8] And also possibly the transposition mentioned in note 4 above.

[9] Against Zahn, (Matthäus, 193Google Scholar), who proposes the reading εıπωσıν καθ' νμων παν πονηρ ον ενεκεν εμου, which is a combination of parts of the two distinctive forms outlined here.

[10] So also Strecker, G., ‘Die Makarismen der Bergpredigt’, NTS 17 (1970–1) 269 n. 4, 270.Google Scholar

[11] It is scarcely to be doubted that the changes wrought on v 11 which resulted in the (B) form of text were intentional, since modifications of such magnitude and coherence are not made thoughtlessly. The suggested time frame for the (B) text is based on its presence in the Old Latin textual tradition, whose origins lie somewhere in the period A.D. 175–200; the intentional ‘edjtorial’ activity that resulted in (B) must therefore have occurred some time prior to ca. A.D. 175. On the subject of early editorial activity and the Bezan text of Matthew, we further M. W. Holmes, ‘Early Editorial Activity and the Text of Codex Bezae in Matthew’ (Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton Theological Seminary, 1984).