Article contents

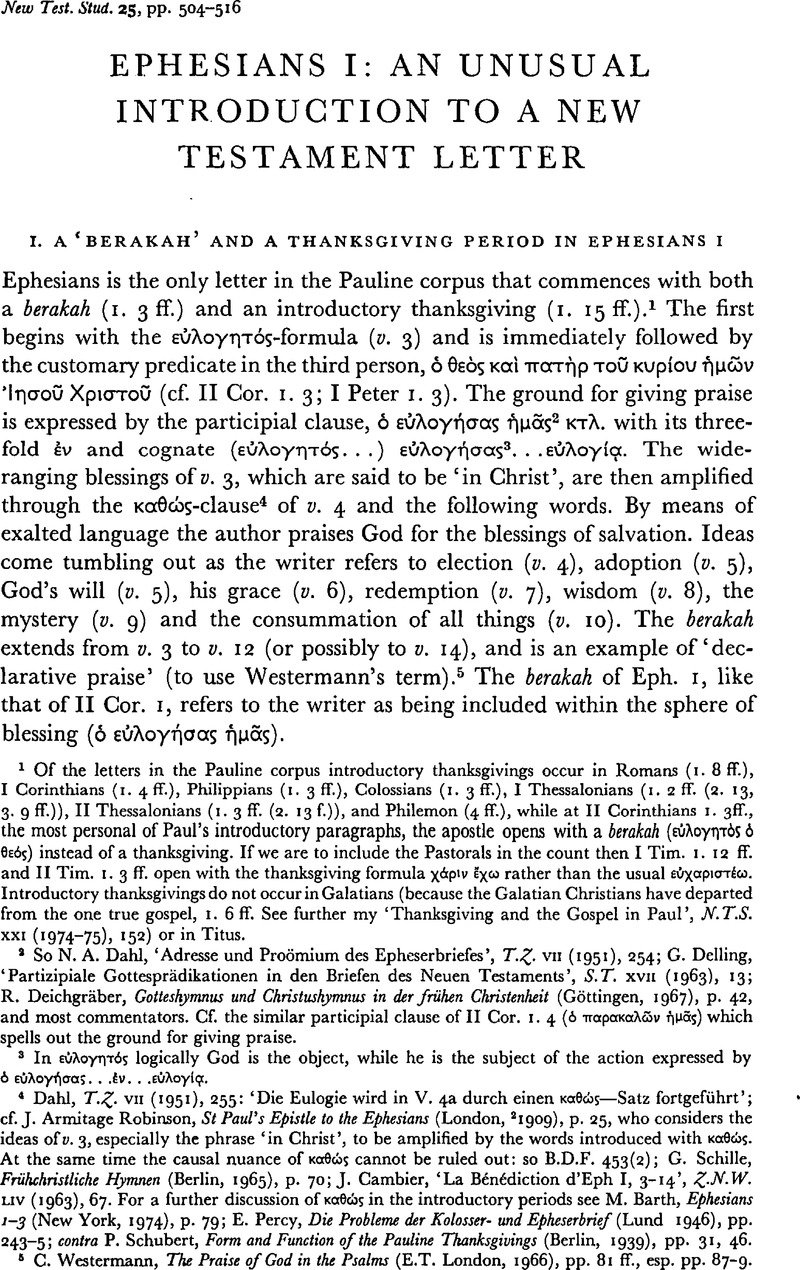

Ephesians I: An Unusual Introduction to a New Testament Letter

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1979

References

1 Of the letters in the Pauline corpus introductory thanksgivings occur in Romans (1. 8 ff.), I Corinthians (1. 4 ff.), Philippians (1. 3 ff.), Colossians (1. 3 ff.), I Thessalonians (1. 2 ff. (2. 13, 3. 9 ff.)), II Thessalonians (1. 3 ff. (2. 13 f.)), and Philemon (4 ff.), while at II Corinthians 1. 3ff., the most personal of Paul's introductory paragraphs, the apostle opens with a berakah (εύλογητός όεός) instead of a thanksgiving. If we are to include the Pastorals in the count then I Tim. 1. 12 ff. and II Tim. 1. 3 ff. open with the thanksgiving formula χ⋯⋯ιν ⋯χω rather than the usual ευχαριστ⋯ω. Introductory thanksgivings do not occur in Galatians (because the Galatian Christians have departed from the one true gospel, 1. 6 ff. See further my ‘Thanksgiving and the Gospel in Paul’, N.T.S. xxi (1974–75), 152) or in Titus.

2 So Dahl, N. A., ‘Adresse und Proömium des Epheserbriefes’, T.Z. 7 (1951), 254Google Scholar; Delling, G., ‘Partizipiale Gottesprädikationen in den Briefen des Neuen Testaments’, S.T. 17 (1963), 13Google Scholar; Deichgräber, R., Gotteshymnus und Christushymnus in der frühen Christenheit (Göttingen, 1967), p. 42Google Scholar, and most commentators. Cf. the similar participial clause of II Cor. 1. 4 (⋯ παρακαλ⋯ν ⋯μāς) which spells out the ground for giving praise.

3 In εύλογητός logically God is the object, while he is the subject of the action expressed by ⋯ εὐλογέσας… ⋯ν… εὐλογíᾳ.

4 Dahl, , T.Z. 7 (1951), 255Google Scholar: ‘Die Eulogie wird in V. 4a durch einen καθώς–Satz fortgeführt’; cf. Armitage Robinson, J., St Paul's Epistle to the Ephesians (London, 2 1909), p. 25Google Scholar, who considers the ideas of v. 3, especially the phrase ‘in Christ’, to be amplified by the words introduced with. καθώς At the same time the causal nuance of καθώς cannot be ruled out: so B.D.F. 453(2); Schille, G., Frühchristliche Hymnen (Berlin, 1965), p. 70Google Scholar; Cambier, J., ‘La Bénédiction d'Eph 1, 3–14’, Z.N.W. 54 (1963), 67Google Scholar. For a further discussion of καθώς in the introductory periods see M. Barth, , Ephesians 1–3 (New York, 1974), p. 79Google Scholar; Percy, E., Die Problem der Kolosser-und Epheserbrief (Lund 1946), pp. 243–5Google Scholar; contra Schubert, P., Form and Function of the Pauline Thanksgivings (Berlin, 1939), pp. 31, 46.Google Scholar

5 Westermann, C., The Praise of God in the Psalms (E.T. London, 1966), pp. 81 ff., esp. pp. 87–9.Google Scholar

6 Note the discussion below.

7 See Schubert's chart, Form, pp. 54 f., and the following note.

8 In this instance the principal verb of thanksgiving does not begin the paragraph. Rather, the opening words, δι⋯ το![]() το κ⋯γώ, link the period with the preceding (either υυ. 3–14 as a whole, or υυ. 13 f. in particular), and the sixth element of this category of introductory thanksgiving (i.e. the causal participial clause, ⋯κούσας τήν καθ' μᾱς πιστιν κτλwhich expresses the basis for thanks giving precedes the principal verb ού παύομαι (εύχαριστ⋯ν) Most other elements of the type I a structure are present: the temporal adverb denoting the frequency with which thanksgiving is offered is expressed by oὐ παύομαι; the pronominal object phrase (ὑπέρ

το κ⋯γώ, link the period with the preceding (either υυ. 3–14 as a whole, or υυ. 13 f. in particular), and the sixth element of this category of introductory thanksgiving (i.e. the causal participial clause, ⋯κούσας τήν καθ' μᾱς πιστιν κτλwhich expresses the basis for thanks giving precedes the principal verb ού παύομαι (εύχαριστ⋯ν) Most other elements of the type I a structure are present: the temporal adverb denoting the frequency with which thanksgiving is offered is expressed by oὐ παύομαι; the pronominal object phrase (ὑπέρ ![]() ); the temporal participial clause with its temporal adverbial phrase (μνεíαν ποιούμε νος ⋯πί τ

); the temporal participial clause with its temporal adverbial phrase (μνεíαν ποιούμε νος ⋯πί τ![]() ν προσευχ⋯ν μου), and the final clause denoting the content of the intercessory prayer (ἵνα ⋯ θεός …δώη, ν. 17) also appear. The only missing element is the personal object of the principal verb (τῷ θεῷ); however, the full title ⋯θεòς το

ν προσευχ⋯ν μου), and the final clause denoting the content of the intercessory prayer (ἵνα ⋯ θεός …δώη, ν. 17) also appear. The only missing element is the personal object of the principal verb (τῷ θεῷ); however, the full title ⋯θεòς το![]() κυρίου ήμ

κυρίου ήμ![]() ν 'lησο

ν 'lησο![]() χριστο

χριστο![]() , ⋯ πατήρ τ⋯ς δóξης, υ 17, found in the intercessory prayer report, makes clear to whom the thanksgiving has been addressed.

, ⋯ πατήρ τ⋯ς δóξης, υ 17, found in the intercessory prayer report, makes clear to whom the thanksgiving has been addressed.

9 For a stylistic and structural examination of this passage see Sanders, J. T., ‘Hymnic Elements in Ephesians 1–3’, Z.N.W. 56 (1965), 220–3Google Scholar, and Deichgräber, Gotteshymnus, pp. 161–5. The latter states: ‘Der Inhalt der Fürbitte…steht in den Versen 17–19, an die sich in V. 20 ein christologisches Stück anschliesst’ (p. 162).

10 Schlier, H., Der Brief an die Epheser (Düsseldorf, 6 1968), pp. 37, 146, 167Google Scholar; and Bruce, F. F., The Epistle to the Ephesians (London, 1961), pp. 59, 66.Google Scholar

11 Theos, Agnostos (Stuttgart, 1956 (= 41923)), p. 253Google Scholar, a statement often quoted by commentators.

12 Masson, C., L'Épître de Paul aux Éphésiens (Neuchâtel, 1953), p. 149.Google Scholar

13 On the style of Eph. 1. 3–14 see: Percy, Problem, pp. 185–91; van Roon, A., The Authenticity of Ephesians (Leiden, 1974), pp. 100–212CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Schlier, Epheser, pp. 39 ff.; and with reference to the Qumran literature Kuhn, K. G., ‘The Epistle to the Ephesians in the light of the Qumran Texts’, in Paul and Qumran, ed. Murphy O'Connor, J. (London, 1968), pp. 115 ff.Google Scholar; F. Mussner, ‘Contributions made by Qumran to the understanding of the Epistle to the Ephesians’, in ibid. pp. 159 ff.; and Deichgräber, Gotteshymnus, pp. 72–5.

14 Ἦς ήχ⋯ριτωσεν, υ. 6; ήν ῷ ἒχομεν, υ. 7; ἦς ήπερλσσευσεν, υ. 8; ἥν ⋯προ⋯θετο, υ. 9; ⋯ν ῴ ήκληρώθημεν, υ. 11; ήν ῷ καì ὐμε![]() ς, υ. 13; ήν ῷ καì πιστεῷσαντες, υ. 13; ήν ῷ καì πιστεὐσαντες, υ. 13; ὅς ήστιν ⋯ρραβών, υ. 14.

ς, υ. 13; ήν ῷ καì πιστεῷσαντες, υ. 13; ήν ῷ καì πιστεὐσαντες, υ. 13; ὅς ήστιν ⋯ρραβών, υ. 14.

16 ‘Ο εὐλήσας, υ. 3; προορíσας, υ. 5; λνωρíσα;ς, υ. 9; ⋯κοὑσαr;ντες… πιστεὑσαντες, υ. 13.

16 Ελναι ⋯μ⋯ς ⋯γλους, υ. 4; ⋯νακεϕαιώσασθαι τ⋯ π⋯ντα, υ. 10; ελς τò ελν⋯ς, υ. 12.

17 κατ⋯ τ⋯ν εὐδοκíαν το ![]() θελήματος αὐτο

θελήματος αὐτο![]() , υ. 5; κατ⋯ τήν βουλήν το

, υ. 5; κατ⋯ τήν βουλήν το![]() θελήματος αὐτο

θελήματος αὐτο![]() , υ.11; cf. υ. 9,

, υ.11; cf. υ. 9,

18 For a survey of these see Schlier, Epheser, pp. 40 f.; Sanders, , Z.N.W. 56 (1965), 224–7Google Scholar; and Deichgräber, , Gotteshymnus, pp. 67–72Google Scholar. One of the more important early works was that of Innitzer, T., ‘Der “Hymnus” im Epheserbrief (1, 3–14)’, Z.K.Th. 28 (1904), 612–21Google Scholar, who separated the passage into three strophes: υυ. 3–6, 7–12, 13–14.

19 Th.Bl. 5 (1926), 120–5.Google Scholar

20 Note the criticisms mentioned by Sanders, Z.N.W. 56 (1965), 224Google Scholar; and Deichgräber, Gotteshymnus, p. 68.

21 Éphésiens, pp. 148 ff.

22 Schille, Hymnen, pp. 65–73, following Käsemann, (‘Epheserbrief,’ in R.G.G.3, 11, cols. 517–20Google Scholar, esp. col. 519), understands the participles of υυ. 5 and 9 (cf. Maurer, C., ‘Der Hymnus von Epheser I als Schlüssel zum ganzen Briefe’, Ev. Th. 11 (1951–1952), 151–72Google Scholar, esp. p. 154) as the key to the formal structure.

23 Coutts', J., suggestion ‘Ephesians I. 3–14 and I Peter I. 3–12’, N.T.S. 111 (1956–1957), 115–27Google Scholar that Eph. 1. 3–12 is a homily based on a liturgical prayer (see below), has been regarded not simply as ‘tentative’ (to use Coutts' own word), but as ‘phantastisch’ (Diechgräber, Gotteshymnus, p. 70).

24 Each of the above-mentioned surveys raises serious, if not devastating, criticisms of these formal divisions.

25 Z.N.W. 54 (1963), 58–104.Google Scholar

26 Ibid. p. 102; cf. pp. 62 ff.

27 Ibid. p. 95.

28 Ibid. pp. 59 f., 103 f. Cf. Martin too, R. P., Worship in the Early Church (London, 2 1974), pp. 33 f.Google Scholar

29 Note the criticisms of Sanders, , Z.N.W. 56 (1965), 255Google Scholar, and Deichgräber, Gotteshymnus, p. 71.

30 Ibid. p. 227. Cf. also Schnackenburg, R., ‘Die grosse Eulogie Eph 1, 3–14’, B-Z. 21 (1977), 67–87.Google Scholar

31 Ephesians, p. 19.

32 Kuhn, loc. cit. pp. 115 ff.; Mussner, loc. cit. pp. 159 ff.; and Deichgräber, , Gotteshymnus, pp. 72–5Google Scholar. I am indebted to Kuhn and Deichgräber for parallels in the Qumran literature with Eph. 1. 3–14.

33 Loc. cit. p. 116. This statement had particular reference to conditional sentences. There are, however, in Eph. 1. 3–14 no instances of parataxis or asyndeton.

34 Loc. cit. p. 120.

35 For the details see Deichgräber, , Gotteshyrmus, pp. 72–5.Google Scholar

36 I QS iv. 3; I QH xi. 28; CD 11. 3.

37 IQpH iv. 27; vii. 4, 27, etc. However, Kuhn points out that in the Qumran texts we usually encounter the plural ‘mysteries’, whereas Ephesians speaks only of “the mystery of Christ”… Herein lies the decisive theological difference: what is new in Ephesians with respect to the Qumran texts is its Christology', loc. cit. p. 119.

38 Lyonnet, S., ‘La bénédiction de Eph. 1, 3–14 et son arrière plan-judaique’, in A la Rencontre de Dieu, Mémorial Albert Gelin (Le Puy, 1961), pp. 341–52.Google Scholar

39 Op. cit. p. 75.

40 Simojoki, M., ‘In Christus’, in Kurze Auslegung des Epheserbriefes, Dahl, N. A. et al. (Göttingen, 1965)1 P. 102Google Scholar, ‘Zur Eigenart unseres Briefes gehört sein meditativer Stil’.

41 Bruce, , Ephesians, p. 15.Google Scholar

42 N. A. Dahl, ‘Bibelstudie über den Epheserbrief’, Auslegung, 11; cf. Deichgräber, , Gotteshymnus, P. 75.Google Scholar

43 For a discussion on hymns in early Christian literature including the criteria for detecting them see Martin, R. P., Carmen Chrisli. Philippians ii. 5–11 (Cambridge, 1967), pp. 1Google Scholar ff. He classifies Eph. 1. 3–14 as a ‘meditative’ hymn of a distinctively Christian variety (p. 19). If, however, the use of parallelismus membrorum and an ascertainable rhythmical lilt when the passage is read aloud be added to Martin's criteria, then it is doubtful whether our paragraph is a hymn (at least in the sense in which I Tim. 3. 16 is a hymn).

44 So Käsemann, , R.G.G. 3, 11, col. 519.Google Scholar

45 Schlier, , Epheser, p. 41.Google Scholar

46 So among others Flemington, Cullmann, Dahl and Coutts. Per contra Dunn.

47 loc. cit. pp. 115 ff.

48 Ibid. p. 125.

49 T.Z 7 (1951), 241 ff.Google Scholar; cf. Kirby, J. C., Ephesians, Baptism and Pentecost (London, 1968), pp. 40 ff.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

50 The passage thus has an epistolary function: ‘…dient die Eulogie als Präludium zum Brief’, Dahl, , T.Z. 7 (1951), 262.Google Scholar

51 Ephesians, p. 27.

52 Ephtser, p. 72. Such an insight, according to Sanders, Z.N.W. 56 (1965), 230Google Scholar, is a ‘breakthrough’ in our understanding of the whole letter.

53 Ev.Th. 11 (1951–1952), 153 ff., and esp. p. 168.Google Scholar

54 Z.N.W. 54 (1963), 58.Google Scholar

55 Allan, J. A., ‘The “In Christ” Formula in Ephesians’, N.T.S. 5 (1958–1959), 54–62, esp. p. 59.Google Scholar

56 The theme of the body, for example, an important motif in Ephesians, does not turn up in the introductory berakah even though related ideas are present. See also Caragounis, C. C., The Ephesian Mysterion (Lund, 1977).Google Scholar

57 On this involved subject apart from the standard introductions (esp. Kümmel, W. G., Introduction to the New Testament (E.T. London, 2 1975), pp. 350 ff.Google Scholar, and the literature cited there) and commentaries (most recently Barth, Ephesians 1–3, pp. 53 ff.) see the treatment of Fischer, K. M., Tendenz und Absicht des Epheserbriefes (Göttingen, 1973)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Chadwick, H., ‘Die Absicht des Epheserbriefes’, Z.N.W. 51 (1960), 145–53.Google Scholar

58 See above, n. 8.

59 So among others Schubert, Form, p. 44; and Kirby, , Ephesians, p. 131Google Scholar. Barth, , Ephesians 1–3, p. 161Google Scholar, correctly points out, contra Schubert, that this argument against the authenticity of Ephesians is unconvincing.

60 Beare, F. W., ‘The Epistle to the Ephesians’, Interpreter's Bible 10 (New York, 1953), 613.Google Scholar

61 Ephesians, p. 131.

62 In my Introductory Thanksgivings in the Letters of Paul (Leiden, 1977), pp. 237–9.Google Scholar

63 The precise significance of δι⋯ το![]() το is disputed.

το is disputed.

64 The change to the second person plural in υυ 13 f. has been explained by scholars along the following lines. (I) ήν ῷ κα⋯ ὐμεἴς κτλ. is said to refer to the recipients of the letter, while the preceding {υυ. 3–12) concerns God's blessings to all Christians. (2) In υυ 11 and 12 the first person plural is restricted in meaning to apply to Jewish Christians (υis-à-υis υυ. 3–10 which refer to all believers), while the second person plural of υυ 13 f. has reference to Gentile Christians. (3) υυ 13 f. refer to the readers who are contrasted with the first generation of Christians (cf. Heb. 2. 3 f.). (4) Cerfaux makes the distinction between the apostles (‘us’) and Christians in general (‘you’). (5) The opening words of the berakah are thought to apply to all Christians. The ‘you’ of υυ 13 f. has reference to new converts, or to the newly baptized. What has happened to them has already taken place in the experience of those Christians who ‘first hoped in Christ’. Our preference is for the second view. In this case υυ 11 f. apply to Jewish Christians who hoped in Christ before others (cf. Rom. 1. 16 f.); or they have reference to the Jewish hope before the Christ came (ήν ![]() χριστῷ), while υυ 13 f. refer to the recipients of the letter - that is, Gentile Christians.

χριστῷ), while υυ 13 f. refer to the recipients of the letter - that is, Gentile Christians.

66 Correctly noted by Schlier, Epheser, p. 69.

66 Cf. my article N.T.S. 21 (1974–1975), 144–55.Google Scholar

67 Chadwick, H., ‘Ephesians’, Peake's Commentary on the Bible (London, 3 1962), p. 983.Google Scholar

68 We have shown elsewhere (see Introductory Thanksgivings, pp. 13–15, etc.) that Paul's introductory thanksgiving paragraphs have a varied function: (a) epistolary - to introduce and indicate the main theme(s) of their letters; (b) didactic - to instruct the recipients either by way of recall to previous teaching or by fresh guidance about what the apostle considers to be important; (c) paraenetic - to introduce exhortatory thrusts (particularly in the intercessory prayer reports) on issues where the recipients need to be challenged. At the same time the introductory paragraphs with their prayer reports are evidence of (d) Paul's deep pastoral and apostolic concern.

- 2

- Cited by