Article contents

The Commands in I Peter II. 17

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1965

References

page 279 note 2 ‘Quisquis Deum timet, fratres suos amat et totum humanum genus quo decet affectu complectitur, is regibus honorem habebit’ (Corp. Ref. LXXXIII (Braunschweig, 1896), p. 247).Google Scholar

page 279 note 3 In Meyer's Kommentar (1887), ad loc.Google Scholar

page 279 note 4 In Lietzmann's Handbuch (1930) 2 1951, ad loc.Google Scholar

page 279 note 5 The First Epistle of St Peter2 (1947), ad loc.Google Scholar

page 279 note 6 The First Epistle of St Peter (1898), ad loc.Google Scholar Similarly, Wohlenberg, G. in Zahn's Kommentar 3 (1923), p. 73.Google Scholar

page 279 note 7 In Meyer's Kommentar (1877), ad loc. (Engl. transl. 1881, p. 134).Google Scholar

page 280 note 1 A solution prompted by despair has been put forward by Wilson, J. P. (Exp. Times, LIV, pp. 193 f.Google Scholar) who suggests a full stop after τıμήσατε or τıμήσατε; cf. Moule, C. F. D., An Idiom Book of N. T. Greek3 (1960), p. 21.Google Scholar

page 280 note 2 The problem was urgent enough: the Jews had been accused of giving ‘non regibus … adulatio, non Caesaribus honor’ (Tac. Hist. v, 5Google Scholar) and the Christians were likely to incur the same suspicion.

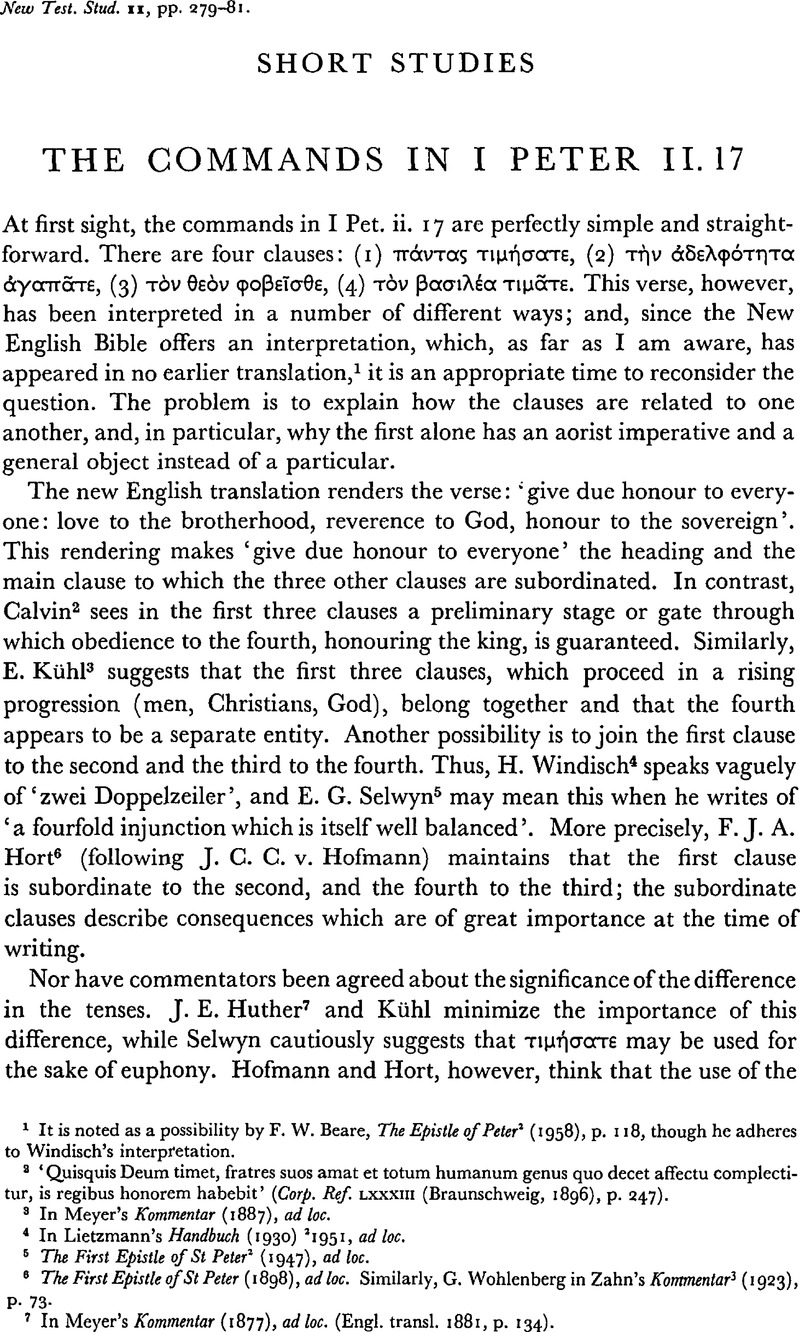

page 280 note 3 We are close to the old exegesis of Hofmann, Die heilige Schnft, VII, I (1875), p. 87.Google Scholar The fear of God is normative for the love of the (= ![]() means here the closer circle of the Christian community, as in v. 9; I Cl. ii. 4; Herm. mand. viii. 10 (?). The admonition follows the line of Jewish formulae, which stress the special responsibility for the

means here the closer circle of the Christian community, as in v. 9; I Cl. ii. 4; Herm. mand. viii. 10 (?). The admonition follows the line of Jewish formulae, which stress the special responsibility for the ![]() ), and, as it seems, the honouring of the king for the honouring of everyone. Thus, God and king are clearly distinguished from each other. The common explanation by which reverence for kings is rooted in the fear of God is not based on the text itself.

), and, as it seems, the honouring of the king for the honouring of everyone. Thus, God and king are clearly distinguished from each other. The common explanation by which reverence for kings is rooted in the fear of God is not based on the text itself.

page 280 note 4 There seems to be a tendency to put the general clauses in a different tense. Herm. mand. 8. 2 ff.Google Scholar and I Pet. ii. 17 have the aorist imperative but II Tim. iv. 5 begins with a present imperative (νηϕε έν πασıν) and proceeds with a third person imperative aorist. For the use of different imperatives in one sentence see also Rom. vi. 13 and cf. Blass-Debrunner, , Grammatik (1954), §337. 2.Google Scholar

page 280 note 5 Z.N.W. (1958), pp. 145 ff.Google Scholar Eph. ii. 12 be gives another good example: άπηλλοτρıωμένοı… and άθεοı… belong together in the same way as ξένοı… and έλπίδα μή έχοντες.

page 281 note 1 Cf. iii. 18; Eph. v. 22; I Cl. xxi. 6.Google Scholar

page 281 note 2 Cf. the structure in chapter iii, where vv. I a, 2 on the one hand and v. 7 ab (up to ![]() ωης on the other-sentences each consisting of two lines-form the basis, which was enlarged subsequently.

ωης on the other-sentences each consisting of two lines-form the basis, which was enlarged subsequently.

page 281 note 3 A Solution, completely different from the one suggested above, has been put forward by Barnikol, E. (in Festschrjft E. Klostermann = Texte u. Unters. vol. 77 (1961), pp. 127–9).Google Scholarmaintains, B. that ii. 11–17 are one entity dealing with πάροıκοı, into which vv. 13, 14Google Scholar and 17d were inserted (‘alsob es am Ende der Zeiten und Obrigkeiten darauf ankäme’) at the end of the second century. His thesis, as far as it is based on the text itself, is only the consequence of Kühl's climactic interpretation, following the lines of which the fourth clause is to be seen either as the main imperative or as a rather unsuitable annex.

- 3

- Cited by