No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

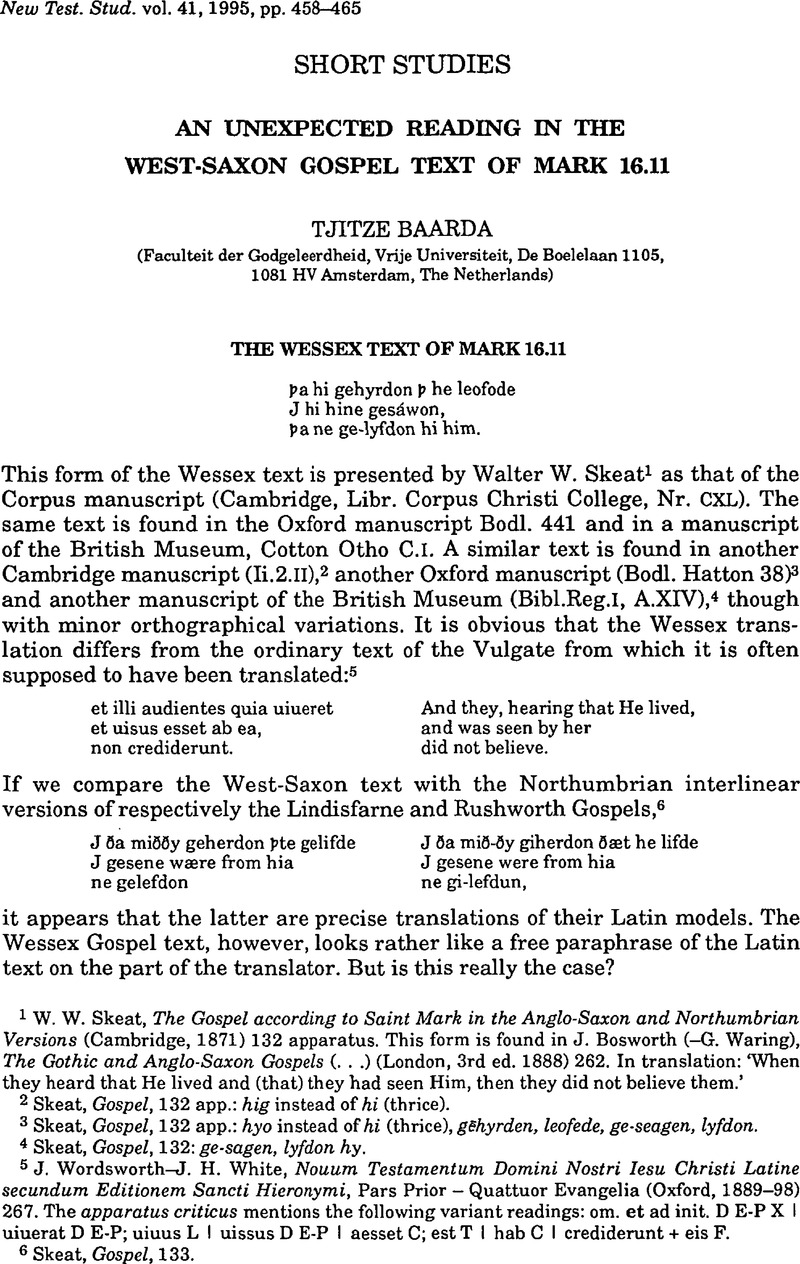

An Unexpected Reading in the West-Saxon Gospel Text of Mark 16.11

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1995

References

1 Skeat, W. W., The Gospel according to Saint Mark in the Anglo-Saxon and Northumbrian Versions (Cambridge, 1871) 132Google Scholar apparatus. This form is found in Bosworth, J. (Waring, -G.), The Gothic and Anglo-Saxon Gospels (…) (London, 3rd ed. 1888) 262Google Scholar. In translation: ‘When they heard that He lived and (that) they had seen Him, then they did not believe them.’

2 Skeat, Gospel, 132 app.: hig instead of hi (thrice).

3 Skeat, Gospel, 132 app.: hyo instead of hi (thrice), gēhyrden, leofede, ge-seagen, lyfdon.

4 Skeat, Gospel, 132: ge-sagen, lyfdon hy.

5 White, J. Wordsworth-J. H., Nouum Testamentum Domini Nostri Iesu Christi Latine secundum Editionem Sancti Hieronymi, Pars Prior – Quattuor Evangelia (Oxford, 1889–1898) 267Google Scholar. The apparatus criticus mentions the following variant readings: om. et ad init. D E-P X uiuerat D E-P; uiuus L uissus D E-P aesset C; est T hab C crediderunt + eis F.

6 Skeat, Gospel, 133.

7 Cf. Legg, S. C. E., Novum Testamentum Graece secundum Textum Westcotto-Hortianum (Oxford, 1935)Google Scholarin loco, notes: εκεινΟι tant. LU ψ 127 472 892 1071 vg. (3 Mss.) Sy.pesh (1 Ms) Arm.; von Soden, H., Die Schriften des Neuen Testaments 2 (Göttingen, 1913) 232Google Scholar, app. 2; Wordsworth-White, Novum Testamentum, 267; A., Jülicher, ed., Itala, Das Neue Testament in altlateinischer Überlieferung 2: Marcus-Evangelium (Berlin, 2nd ed. 1970) 159Google Scholar, does not mention the Old Latin r 2 (which Von Soden mentions here).

8 The introduction of an active voice is not restricted to the Wessex Gospel, it is found also in Coptic versions (idiomatical) and Arabic versions (see below), whereas it is present in several modern translations, cf. e.g. NEB ‘that she had seen him’, the Dutch version of Mark ‘Macht, het Evangelie van Marcus’ (NBG), ‘dat zij hem gezien had’.

9 So Ms. C (the edited text om. non and ei?); cf. Hilberg, I., Sancti Eusebii Hieronymi Epistulae 2 (CSEL 55; Vienna-Leipzig, 1912) 470–513Google Scholar (‘Ad Hedybiam de Quaestionibus Duodecim’), esp. 481:11–12.

10 This is the suggestion of Th. Beza, Jesu Christi Domini Nostri Novum Testamentum sive Novum Foedus … (Cambridge, 1642) 148: ‘Syrus interpres … pro ππ αύτῆς, ab ea, ύπ αύτῶν, ab eis’.

11 So Legg, Novum Testamentum, in loco, app.

12 Unless Beza really had access to a Greek manuscript with this reading (‘ύπ αύτῶν …, ut in uno etiam Graeco exemplari legimus’); it is possible, but not very probable.

13 Could this unexpected reading be a miswriting of either αύταίς or αύτῆ ό Ίησοες (=ΑΥΤ<Η>ΟΙΣ)?

14 Horner, G., The Coptic Version of the New Testament in the Northern Dialect (Oxford, 1898) 476 app.Google Scholar

15 Tischendorf, C., Novum Testamentum Graece 1 (editio octava; Leipzig, 1872) 408Google Scholar mentions the fact that the Vulgate Codex Fuldensis [sic], Jerome and the Anglo-Saxon text have ‘ei’[sic], to which he adds the Greek Codex Bezae καί ούκ έπίστευσαν αύτῆ (he adds *αύτῶ which means that the codex has actually αύτῶ); von Soden, H., Die Schriften des Neuen Testaments (…) 2 (Göttingen, 1913) 232Google Scholar notes the reading καί ούκ έπίστευσαν αύτῆ for Tα (= Arabic Diatessaron [sic] and D (*αύτῶ). Legg, o.c, in loco, notes the same reading for D, but adds: (αυτω D*). We shall deal with these data, which are partly incorrect, in our discussion of the text.

16 I present here the text of the Codex Fuldensis (F), Ranke, E., Codex Fuldensis, Novum Testamentum Latine interprete Hieronymo ex manuscripto Victoris Capuani (Marburg/Leipzig, 1868) 158–60Google Scholar, esp. 160.7–11 (second part of ch. 176); cf. the same text in Codex Sangallensis (G) in Sievers, E., Tatian, Lateinisch und altdeutsch (Paderborn, 2nd ed. 1960) 274–9Google Scholar, esp. 278.38–40, 279.1–9 (ch. 175 second part); in the Codex Casselanus (C), Grein, C. W. M., Die Quellen des Heliand, Anhang: Tatians Evangelienharmonie herausgegeben nach dem Codex Casselanus (Kassel, 1869) 257Google Scholar (ch. 178).

17 Sievers, Tatian, 279.4–6.

18 M. Vattaso-A. Vaccari, Diatessaron Toscano, Part 2 of Todesco, V., Vaccari, A., Vattaso, M., Il Diatessaron in Volgare Italiano (Città del Vaticano, 1938) 362.5–6.Google Scholar

19 V. Todesco, Il Diatessaron Veneto, Part 1 of V. Todesco a.o., Diatessaron, 160.36–7 (‘And they, having heard from her, that Jesus lived, and was seen by her, did not believe’).

20 Cf. D. Plooij-C. A. Phillips-A. H. A. Bakker, The Liège Diatessaron vol. 2, part 8 (Amsterdam/London, 1970) 768 app. ad John 20.18, Ibid., 769 app.ad Mark 16.12. ‘Liège’ reads after Matt 28.10/Mark 16.10, ‘Ende alse die yongren dit hoerden so dochtt hen doerheit ende ghedwesnessen end gheloefdens nit’, a text which agrees with Luke 24.11 rather than Mark 16.11 (an abbreviation of the text found in the Codex Fuldensis, at a different place in the narrative).

21 The Vita beate Virginis Marie et salvatoris Rhythmica (ed. A. Vöglin; Tübingen, 1888) 210Google Scholar, ll. 6200–3) has a text that may have been derived from some sort of harmony like this, where it reads: ‘… quod ipsae redivivum dominum vidissent (active!) … Sed cum illi mulierum sermones audiverunt, has errare reputabant, nec eis crediderunt’. There are two agreements with the Wessex version here.

22 Ph. Pusey, E., Gwilliam, G. H., Tetraevangelium Sanctum juxta Simplicem Syrorum Versionem (Oxford, 1901) 312Google Scholar (one Ms. without the initial ‘and’). Legg, Novum Testamentum, in loco, registers the Peshitta as reading έθεάθη αύταίς.

23 Marmardji, A.-S., Diatessaron de Tatien (Beyrouth, 1935) 512Google Scholar; Ciasca, A., Tatiani Evangeliorum Harmoniae Arabice (Rome, 1888) 202Google Scholar (Arab.); Ciasca, o.c, 95 (tr.), ‘Et illi, cum audissent eas dicentes, quod ipse viveret, et apparuisset eis, non crediderunt’, Hill, J. Hamlyn, The Earliest Life of Christ (…), The Diatessaron of Tatian (Edinburgh, 2nd ed. 1910)Google Scholar, ‘And they, when they had heard them saying that he was alive, and had appeared to them, believed not’, and even Preuschen, E., Tatians Diatessaron aus dem Arabischen übersetzt(Heidelberg, 1926) 234Google Scholar, ‘Und sie, als sie gehört hatten, (was) sie sagten, daβ er lebe und ihnen erschienen sei, glaubten sie nicht’, forgot to render eis after crediderunt.

24 Levin, B., Die griechisch-arabische Evangelien-Übersetzung, Vat. Borg. ar. 95 und Ber. orient, oct. 1108 (Uppsala, 1938) 90Google Scholar (Arab.).

25 Lagarde, P. de, Die vier Evangelien Arabisch aus der Wiener Handschrift herausgegeben (Leipzig, 1864) 65.31–2Google Scholar; cf. xxvi, under 65.32.

26 The Walton Polyglott presents us with the reading ‘and she’ in a text that is almost similar to Lagarde's text, cf. Walton, B., Biblia Sacra Polyglotta vol. 5 (London, 1657) 243.Google Scholar

27 De Lagarde, o.c, vi-vii (with his remarkable style): ‘dass ich offenbare fehler verbessert, verstand sich von selbst: dass ich diese falschen “lesarten” zwischen runden klammern noch aufführte, nicht so sehr: ich habe es um der auch in diesem gebiete umherschnüffelnden meute des Mephistopheles willen dennoch gethan, die … leicht dem geehrten theologischen publikum sand in die augen werfen könnte: man kennt das nach gerade … ich bereue auch bitter, meinen text durch aufführung des zwischen () stehenden verunstaltet zu haben’. However, here he threw dust in our eyes and we may be glad that he added the wrong readings in brackets, so that we know what the manuscript actually read.

28 Zuurmond, R., Novum Testamentum Aethiopice, The Synoptic Gospels part 2: Edition of the Gospel of Mark (Äthiopistische Forschungen 27; Stuttgart, 1989) 296Google Scholar; letter of the author d.d. 23th of September, 1992, with some clarification on his collation.

29 Cf. Zuurmond, Novum Testamentum 1.296–7, 396; cf. the stemma, Ibid., 1.133.

30 Zohrab, J., Astowacašownč‘ matean hin ew nor ktakaranac‘ 4 (Venice, 1805) 110Google Scholar app.; the text given by Zohrab reads ![]() ‘to her’.

‘to her’.

31 Künzle, B. O., Das altarmenische Evangelium 1 (Bern/Frankfurt/Nancy/New York, 1984) 133.Google Scholar

32 Blake, R., The Old Georgian Version of the Gospel of Mark (PO 20.3; Paris, 1928) [140] 574.Google Scholar

33 Cf. also Peters, C., ‘Der Diatessarontext von MT 2, 9 und die westsächsische Evangelienversion’, Biblica 23 (1942) 323–32.Google Scholar

34 One may wonder why Wilckens, U. (Das Neue Testament [Hamburg/Köln/Zürich, 2nd ed. 1971] 198)Google Scholar has rendered the Greek text with ‘Als sie hörten, er sei am Leben und sei von ihnen gesehen worden, wollten sie es nicht glauben.’

35 Junius, F., Th. Mareschallus, Quatuor D. N. Jesus Christi Evangeliorum Versiones perantiquae duae, Gothica scil. & Anglo-Saxonica (…) (Amsterdam, 1684), esp. 495–509Google Scholar (passim); cf. Kuster, J. Mill-L., Novum Testamentum Graecum (…) (Leipzig, 1710)Google Scholar, Prolegomena, p. 152 (1401); cf. 161 (1462).