No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Thomas, Logion 30

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1979

References

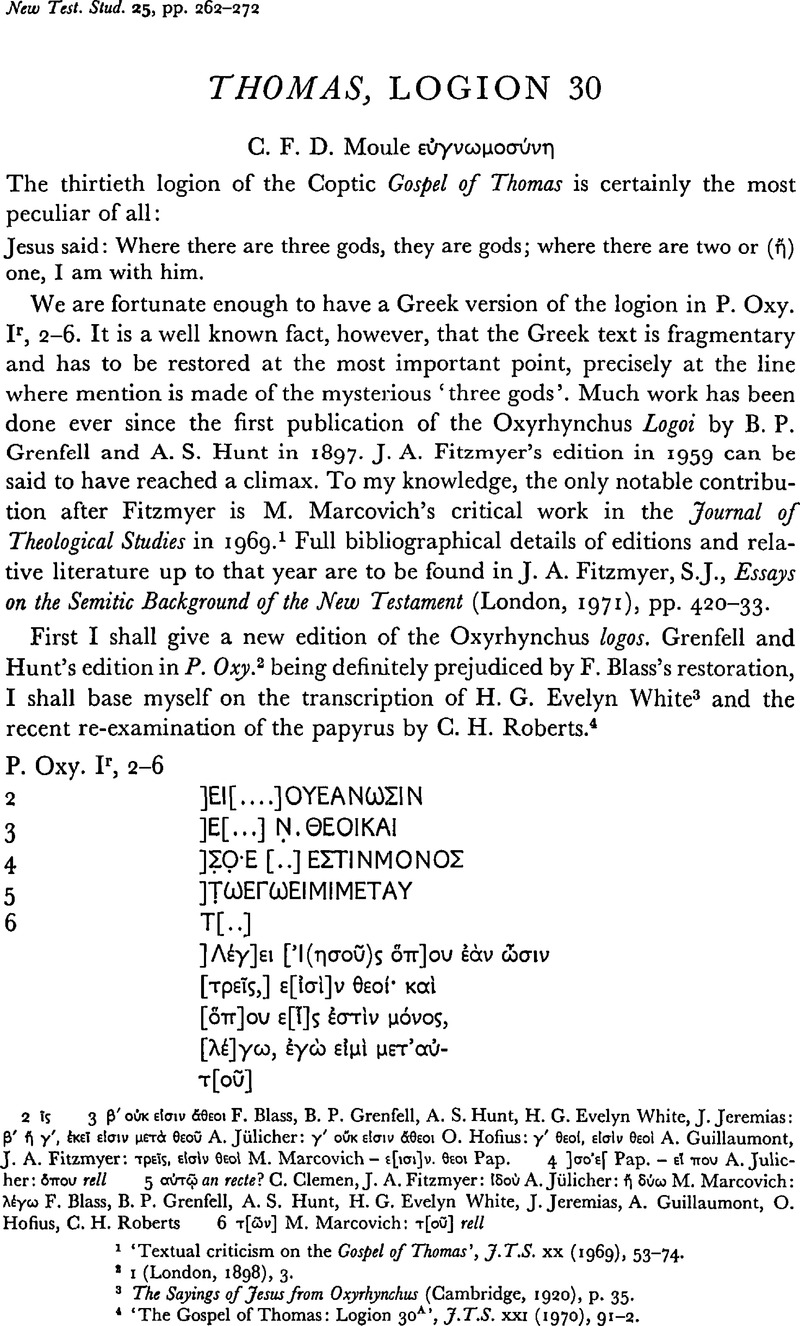

page 262 note 1 ‘Textual criticism on the Gospel of Thomas’, J.T.S. 20 (1969), 53–74.Google Scholar

page 262 note 2 1 (London, 1898), 3.

page 262 note 3 The Sayings of Jesus from Oxyrhynchus (Cambridge, 1920), p. 35.Google Scholar

page 262 note 4 ‘The Gospel of Thomas: Logion 30A’, J.T.S. 21 (1970), 91–2.Google Scholar

page 265 note 1 Cf. Resch, A.. Agrapha (Leipzig, 1906) nr. 50 and 175Google Scholar. In so far as this logion never appears, to my knowledge, separated from the Matthean logion, properly speaking it cannot be considered as an independent agraphon; it is a complement to a canonical Dominical saying.

page 265 note 2 Ign. Eph. v, 2, ε⋯ γ⋯ρ ⋯νòς κα⋯ δευτ⋯ρoυ πρoσευχ⋯ τoσα⋯την ἰσχὺν έχει can in no way be considered as the earliest occurrence. As the Committee of the Oxford Society of Historical Theology noted in The New Testament in the Apostolic Fathers (Oxford, 1905, p. 77), ‘here Ignatius's ⋯νòς κα⋯ δευτ⋯ρoυ = δυoῑν’. In Ignatius we are concerned with an echo of Matt, xviii. 19, the parallel of which in the Gospel of Thomas is to be found in Log. 48, not in Log. 30.

page 265 note 3 Cf. Harl, M., ‘Á propos des Logia de Jésus: le sens du mot MONAXOΣ,’ Revue des Études Grecques 73 (1960), 464–74CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Klijn, A. F. J., ‘The “Single One” in the Gospel of Thomas’, J.B.L. 81 (1962), 271–8Google Scholar; Guillaumont, A., ‘Le nom des “agapétes“’, Vigiliae Christianae 23 (1969), 30–7Google Scholar; idem, ‘Monachisme et ethique judéo-chrétienne’, Recherches de science réligieuse 60 (1972), 199–218Google Scholar; Morard, F.-E., ‘Monachos, Moine. Histoire du terme grec jusqu'au 4° siécle’, Freiburger Zeitschrift für Philosophic und Theologie 20 (1973), 332–411Google Scholar. For the Jewish background of the early Christian yeh⋯îdîm see also Néher, A., ‘Échos de la secte de Qumran dans la littérature talmudique’ in Les Manuscrits de la Mer Morte. Colloque de Strasbourg, 25–27 mai 1955 (Paris, 1957), pp. 45–60.Google Scholar

page 265 note 4 Dom Louis Leloir, O.S.B., , Saint Éphrem, Commentaire de l'Évangile Concordant. Texte syriaque (Manuscrit Chester Beatty 709) (Dublin, 1963), p. 135.Google Scholar

page 265 note 5 For a ‘very tentative’, but still very plausible, stemma of the transmission of the Gospel of Thomas cf. M. Marcovich, op. cit. p. 74. For the chronology of the gospel cf. Ménard, J.-E., ‘Les problémes de l'Évangile selon Thomas’, in Krause, M. (ed.), Essays on the Nag Hammadi Texts in Honor of Alexander Böhlig (Leiden, 1972), pp. 59–73, esp. pp. 72–3.Google Scholar

page 266 note 1 ‘Sémitismes dans les logia de Jésus retrouvés à Nag-Hammâdi’, Journal Asiatique 296 (1958), 113–23, esp. pp. 114–16.Google Scholar

page 266 note 2 Cf. Barthélemy, D., ‘Les tiqquné sopherim et la critique textuelle de l'Ancien Testament’, in Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 9 (Leiden, 1963), 285–304Google Scholar; Alexander, P. S., ‘The Targumim and early exegesis of “Sons of God” in Genesis 6’, Journal of Jewish Studies 23 (1972), 60–71CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Wickham, L. R., ‘The Sons of God and the daughters of men: Genesis vi. 2 in early Christian exegesis,’, Oudtestamentische Studiën 19 (1974), 135–47Google Scholar. See the very interesting arguments between R. Simlai (middle of the third century) and the Minim in Herford, R. T., Christianity in Talmud and Midrash (London, 1903), pp. 255 ffGoogle Scholar. Cf. H. F. Weiss, Untersuchungen zur Kosmologie des hellenistischen und palästinischen Judentums (TU 97, 1966), pp. 324 f.

page 266 note 3 Cf. Emerton, J. A., ‘The interpretation of Psalm lxxxii in Jn x’, J.T.S. 11 (1960), 329 ff.Google Scholar; ‘Melchizedek and the Gods; fresh evidence for the Jewish background of John X. 34–6’, loc. cit. 18 (1966), 339–401.Google Scholar

page 267 note 1 Cf. p. 265 n. 3 above.

page 267 note 2 Op. cit. esp. p. 72.

page 267 note 3 Essays, p. 399.

page 268 note 1 Cf. Barbel, J., Christos Angelos (Bonn, 2 1964)Google Scholar; Kretschmar, G., Studien zur frühchristlichen Trinitäts-theologie (Tübingen, 1956), pp. 105 ff.Google Scholar; Grillmeier, A., Christ in Christian Tradition, 1 (E.T. by J. Bowden, London, 2 1975), pp. 47 ffGoogle Scholar. Note the question about the ‘dii’ and the ‘deus’ in the Pseudo-Clementine Recognitions (11. 42 ff.) and Homilies (xviii, 4, 3) and the beliefs of Epiphanius' Ebionites in Panarion, 30, 16, 4 (taken from the ‘Grundschrift’ of the Pseudo-Clementines?).

page 268 note 2 Εῑς Bαιτ, εῑς Αθωρ, μ⋯α τ⋯ν β⋯α, εῑς δ⋯ Aκωρι

χαῑρε π⋯τερ κóσμoυ, χαῖρε τρ⋯μoρφε θεóς

Cf. Bonner, C., Studies in Magical Amulets Chiefly Graeco-Egyptian (Ann Arbor, 1950), p. 175.Google Scholar

page 268 note 3 Sermo xxviii, 5 (P.S. 3, 791, 19 ff.); cf. xxviii, 4 (ibid. 11 ff.).

page 268 note 4 Dem. iv, 11 (P.S. 1, 160–1).

page 269 note 1 Cf. Hippolytus, Elenchus, 5, 23–7. See Salmon's, G. notice in W. Smith and H. Wace, A Dictionary of Christian Biography, 3 (London, 1882), pp. 587–9.Google Scholar

page 269 note 2 F. XIIv.

page 269 note 3 Comment in Matt., 14, 1–4.

page 270 note 1 Clem. Alex., Strom, iii, 68–70. Except in the first paragraph, I follow H. Chadwick's translation in Oulton, J. E. L. and Chadwick, H., Alexandrian Christianity (London, 1954), pp. 71–2.Google Scholar