No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

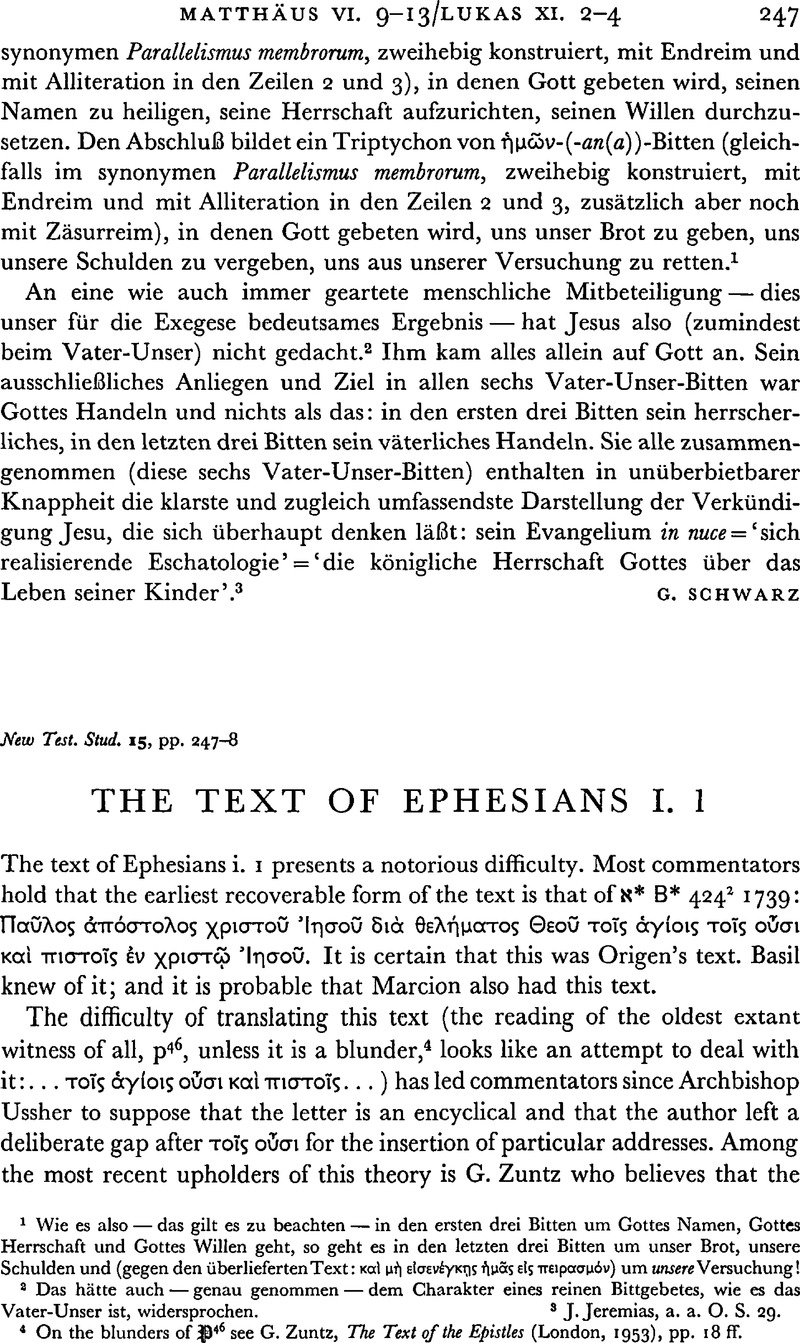

The Text of Ephesians i. 1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1969

References

Page 247 note 1 Wie es also — das gilt es zu beachten — in den ersten drei Bitten um Gottes Namen, Gottes Herrschaft und Gottes Willen geht, so geht es in den letzten drei Bitten um unser Brot, unsere Schulden und (gegen den ϼberlieferten Text: και μί εισενέγκης ήμας είς πειρασμόν) um unsere Versuchung!

Page 247 note 2 Das hätte auch — genau genommen — dem Charakter eines reinen Bittgebetes, wie es das Vater-Unser ist, widersprochen.

Page 247 note 3 Jeremias, J., a. a. O. S. 29Google Scholar.

Page 247 note 4 On the blunders of ![]() see Zuntz, G., The Text of the Epistles (London, 1953), pp. 18 ffGoogle Scholar.

see Zuntz, G., The Text of the Epistles (London, 1953), pp. 18 ffGoogle Scholar.

Page 248 note 1 Zuntz, , op. cit. p. 228 n. I, and pp. 276 f.Google Scholar

Page 248 note 2 Ewald, P., Die Briefe des Paulus an die Epheser, Kolosser und Philemon (Leipzig, 1905), p. 16Google Scholar.

Page 248 note 3 Shearer, W. C., Expository Times, IV, (1892/1893), 129Google Scholar.

Page 248 note 4 Goguel, M., Introduction au NT, IV, 2e partie (1926), 437 fGoogle Scholar. Goguel's reconstruction of the history of the text is most extraordinary. He supposes that his ‘original’ text was expanded by the addition of ![]() (or

(or ![]() ) to produce the reading of the textus receptus, and that the place-name was then dropped (because known to be unoriginal), Producing the text of N*B*, etc. and leaving the words τοίς οũσιν hanging in the air. Goguel also lists some other proposed emendations, ibid. p. 436 n. 3.

) to produce the reading of the textus receptus, and that the place-name was then dropped (because known to be unoriginal), Producing the text of N*B*, etc. and leaving the words τοίς οũσιν hanging in the air. Goguel also lists some other proposed emendations, ibid. p. 436 n. 3.