Introduction

Although Turkey has had a long experience with parliamentary democracy, the trajectory of the Turkish party system reveal that it has an inchoate,Footnote 1 open,Footnote 2 or unstructured party system,Footnote 3 which is reflected in high levels of fragmentation, volatility, and polarization.Footnote 4 There are a variety of reasons for this: military interventions, inefficient governments, factionalism, party closures, party switches, and a lack of intra-party democracy. This poses a challenge to developing a consistent framework that would aid in thoroughly analyzing changes in the Turkish party system.

Within this framework, this paper, above all, seeks to update decades-old research examining party system change in Turkey.Footnote 5 Second, unlike other studies that cover only a time-limited period,Footnote 6 this paper analyses party system change since the establishment of modern Turkey. Third, by consistently adopting Sartori’s party system typology throughout the text, this paper goes beyond taxonomies that do not provide meaningful insights within the context of party system theory.Footnote 7

Against this background, using Sartori’s typology, we examine the change in the Turkish party system based on two criteria: (a) the number of relevant parties and (b) the spatial distance between the parties (the level of polarization). For the former, we look at electoral results and government composition.

While positioning the parties spatially and measuring the level of polarization, on the other hand, we conducted content analysis of the party programs of the respective parties. As WeberFootnote 8 notes, “content analysis is a research method that uses a set of procedures to make valid inferences from text.” Among the types of content analysis, we implemented conceptual analysis. Accordingly, we highlighted the key concepts that frequently repeated themselves in the introductory sections of the party programs and/or in the sections that define the goals and the missions of the relevant parties. Admittedly, content analysis does not fully reveal the ideology of the parties, since, in some cases, the concepts acquire the intended meaning only within the framework of a broader text. Therefore, we also did a hermeneutical reading. For instance, the Justice and Development Party’s (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) emphasis on faith and family in its party program reveals that it was a conservative party from the onset, although the party leadership refrained from calling itself “conservative-democrat” until 2004.

We are well aware that the analysis of party programs also has some limitations. First, party programs largely consist of general and ambiguous expressions. Excluding a few examples, such as the “democratic left” slogan of the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP) in the 1970s or the “idealism” of the Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP), there is hardly any document that fully highlights the ideological orientation of the parties. Second, the party programs of both center-right and center-left parties include similar provisions that make it difficult to highlight the spatial distance between them. Third, in some cases, the party program and political practice do not overlap much or even contradict one another. For instance, while the AKP has a quite liberal program, its policies in government have recently shown fairly authoritarian tendencies.

Considering these constraints, we also used public opinion surveys to inform our arguments. To illustrate, when we refer to political polarization during the 1970s, we draw our conclusions from the party programs rather than surveys, as the latter are, for the most part, missing. In the case of the AKP, however, we rely mainly on public opinion surveys because they exist in abundance.

In this light, based on Sartori’s framework, we call the period from 1923 to 1950 “one-party authoritarianism”; the period from 1950 to 1960 a “predominant party system with a leaning towards a hegemonic party system”; the period from 1961 to 1980 “polarized pluralism driven by a left–right divide”; and the period from 1983 to 2002 “polarized pluralism driven by ethnic and religious cleavages.” Considering the recent authoritarian drift of the AKP government, we call the period from 2002 onwards a “predominant party system with a leaning towards a hegemonic party system.”

With regard to the role of opposition parties in this change, we highlight the following. First, the opposition is highly fragmented. Second, the opposition tends to be more antagonistic toward each other than toward the governing party, illustrating the existence of what Sartori calls “bilateral opposition.” Third, the opposition lacks any comprehensive program to persuade voters. The combination of these elements leads to a cycle in which right-wing parties reproduce their dominance even if they do not have an attractive program and merely rest their appeal on social divisions. Overall, we suggest that while fragmented opposition led to the emergence of a one-party government and/or military intervention because of the high polarization it induces (e.g. in the 1970s and 1990s), the existence of a bilateral opposition prolongs one-party governments (e.g. the November 2015 elections) as voters vote primarily to defeat the opposition camp. It must be emphasized that this hypothesis works for the post-1960 period because before that there was neither fragmentation nor bilateral opposition.

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we define the typologies of the party systems. Then, we justify why a certain period belongs to a certain party system type and then discuss the causal argument, namely, the role of the opposition in the party system change.

Typologies of the party systems

The party system not only defines the number of players but also the distribution of resources and capabilities among them.Footnote 9 To examine and locate different party systems, scholars have developed distinct typologies. The rationale behind this is pragmatic: typologies simplify extremely complex realities.Footnote 10

Contrary to Mair,Footnote 11 who suggested that “the classification and typologies of party systems is by now a long-established art,” the recent changes in the political landscape in western Europe—notably the rise of extreme right and radical left parties—make it necessary to revisit the long-established party system typologies. However, since the publication of Sartori’s book on parties and party systems in 1976, no serious effort has been made to enhance our understanding of party systems.Footnote 12 Therefore, the confusion about classifications persists.Footnote 13

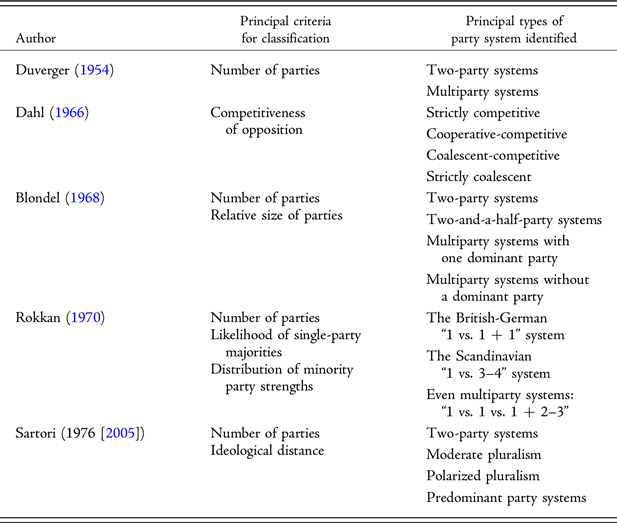

Sartori developed the most comprehensive of the wide-ranging typologies, generated by distinct criteria and summarized in Table 1. On party typologies, Sartori contends that “almost every writer comes up with his own scheme” and thus “confusion and profusion of terms seems to be the rule.”Footnote 14 Behind this confusion lies the absence of counting rules. He suggests overcoming this confusion by introducing “irrelevance criteria,” which discount parties that have neither a “coalition” nor “blackmail potential.” Simply put, a party has coalition potential if other parties consider it to be a feasible coalition partner, and a party has blackmail potential if it intimidates ruling parties even when it is in opposition.Footnote 15

In addition to irrelevance criteria, Sartori considers the spatial distance between the parties in developing his typology. Broadly speaking, spatial distance refers to political parties’ attitudinal position toward one another and vis-à-vis the regime. This brings the concept of an “anti-systemic party” to the forefront. Typically, an anti-systemic party – such as the Italian Communist Party or the Alternative for Germany (AfD) in Germany – has the potential to undermine the legitimacy of the party system through veto. Moreover, it is capable of influencing the dynamics of the party system, be it in a “centrifugal” or a “centripetal” way.Footnote 16

Overall, considering the number of relevant parties and the level of polarization in the system, Sartori develops nine types, some of which will be highlighted in detail in the next section. Despite its merits, however, Sartori’s typology has been contested on several grounds: the overcrowding of the systems of “moderate pluralism,”Footnote 17 the absence of a real “two-party system,” and the exhaustion of systems of “polarized pluralism.”Footnote 18 Moreover, Von BeymeFootnote 19 contends that Sartori overlooked the social and structural considerations that actually shape the party system. Another view proposes that Sartori’s emphasis is on the nuances of the party system rather than on its properties,Footnote 20 referring to his taxonomical categorization.

Against this critical backdrop, we adopt Sartori’s typology because it is the most innovative and the most advanced: it encompasses the degree of consolidation of the party system, the manner of alternation of power, the quality of opposition, and the general dynamics of party systems (centripetal vs. centrifugal) within a time- and context-sensitive framework.Footnote 21 Similarly, Sartori’s typology performs better than alternative typologies in that it highlights the interactions between parties and thereby denotes the functioning of the party system.Footnote 22

Having underlined the properties of Sartori’s typology, the next section applies it to Turkey. Table 2 highlights our findings.

Table 2. Summary of party system change in Turkey

Notes: * Interrupted by military intervention/memorandum.

** Anti-systemic parties are those that have vote power or are capable of influencing the dynamics of the competition, be it in a centrifugal or a centripetal direction (Sartori, 1976 [Reference Sartori2005]).

*** Fragmentation is high if five or more parties actively shape the party system (Sartori, 1976 [Reference Sartori2005]).

CKMP (Republican Peasants and Nation Party or Cumhuriyetçi Köylü Millet Partisi); YTP (New Turkey Party or Yeni Türkiye Partisi); MGP (National Reliance Party or Milli Güven Partisi); CGP (Republican Reliance Party or Cumhuriyetçi Güven Partisi); BDP (Peace and Democracy Party or Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi); DSP (Democratic Left Party or Demokratik Sol Parti); DTP (Democratic Society Party or Demokratik Toplum Partisi).

1923–1950: one-party authoritarianism

The CHP maintained a one-party rule from the foundation of the Turkish Republic until 1950. As a general tendency, the CHP’s rule was authoritarian, not totalitarian, because it mobilized a corporatist ideologyFootnote 23 and was not interested in regulating the private sphere. In the same vein, unlike totalitarian regimes, political and social mobilization was circumscribed.Footnote 24

During the single-party period, the ruling elites allowed the establishment of the Progressive Republican Party (Terakkiperver Cumhuriyet Fırkası, TCF) in 1924 and the Free Republican Party (Serbest Cumhuriyet Fırkası, SCF) in 1930. The regime’s tolerance of these parties diminished, however, as they started to become credible alternatives.Footnote 25 While the TCF was banned after the assassination attempt on Mustafa Kemal in Izmir, the SCF dissolved itself upon Mustafa Kemal’s request. The allegation was the same: they had become the center of anti-secular activities. This rationale persisted in the following decades and laid the groundwork for the dissolution of the religious-based parties.

Why did the Kemalist elites allow party pluralism, even for a short period of time? The relevant literature suggests that authoritarian regimes allow party pluralism for a variety of reasons, ranging from a desire to monitor their own successFootnote 26 to alleviating possible tensions between the ruler and the ruling elite.Footnote 27 In the Turkish case, the inclusion of the opposition was clearly aimed at expanding the legitimacy of the regime. Once this failed, the checks and balances mechanism was bypassed, which further intensified one-party control.Footnote 28

An absence of party pluralism does not amount to saying that there was no opposition. On the contrary, the opposition was organized within the ruling party. From the outset, intra-party contestation between the étatists and the liberals was intense. While the liberals overwhelmed the étatists during the 1920s, the balance of power shifted to the étatists after the 1929 economic crisis.Footnote 29 As Solinger argues, intra-party opposition has the potential to weaken one-party regimes.Footnote 30 And this is exemplified in the collapse of CHP rule in 1950.

1950–1960: From the predominant party system to the hegemonic party system

In 1945, reacting to the land reform program, four deputies resigned from the CHP and founded the Democrat Party (Demokrat Parti, DP). The DP came to power in 1950 and won the elections in 1954 and 1957. It remained in power until it was ousted by military intervention in 1960.

We call the period between 1950 and 1957 a “predominant party system with a leaning towards a hegemonic party system.” According to Sartori, a predominant party system emerges if a party wins three elections in a row by a double-digit margin under a competitive party system. Based on this criterion, the DP succeeded in changing the party system into a predominant one.

During the 1950s, a major contestation took place between the DP and the CHP. Although niche parties, such as the Nation Party (Millet Partisi, MP), were popular for some time, they could never translate that popularity into a parliamentary seat because of a first-past-the-post electoral system that typically empowers large parties and underrepresents small ones.Footnote 31 In this light, the election results show that even the second party (CHP) was highly underrepresented. Accordingly, the DP sustained its super-majority in the parliament despite the substantial decline in its vote share in the 1957 elections.

Under any given standard, the spatial distance between the DP and the CHP does not suffice to put them in opposing camps, at least in the early 1950s. The difference between these two parties was non-ideological in character and mainly hinged on some policy issues.Footnote 32 When the DP attempted to strengthen its position in the political system and began to adopt populist authoritarian policies toward the end of the 1950s,Footnote 33 the gap between the discourse and the practice of the party became wider. In response to this, the CHP leadership started to address voters through a more reformist/progressive discourse and policy agenda.Footnote 34

The nature of the relations between the opposition parties must also be noted. Although the MP formulated its program against the CHP in the beginning, it mainly opposed the DP, from which it was born and whose place it wanted to fill.Footnote 35 This accelerated the demise of the DP as the opposition parties concentrated their efforts on terminating one-party rule rather than weakening each other.

Despite exhibiting the characteristics of a “predominant party system” for a long time, the Turkish party system transformed into a “hegemonic party system” toward the end of DP rule.Footnote 36 As SartoriFootnote 37 notes, the hegemonic party system can be distinguished from a predominant party system in three respects. First, unlike a predominant party system, which belongs to competitive politics, a hegemonic party system is non-competitive, implying that an alternation in power is not possible. The hegemonic parties typically eliminate competition using several instruments, ranging from legal arrangements to repression. The DP’s attempt to confiscate the CHP’s party property through the “Investigation Committee” (Tahkikat Komisyonu),Footnote 38 its pressuring of the media, and its imposition of police control on the opposition illustrate the DP’s desire to eliminate competition.Footnote 39 The legal arrangements, on the other hand, included the downgrade of Kırşehir’s status as a province and the split of Malatya province after voting predominantly for the MP. Second, a hegemonic party is more powerful than a predominant party. For instance, it may change the constitution unilaterally. The DP had enough of a majority to change the constitution during each term. Third, electoral malpractice is frequent.Footnote 40

Eventually, the declining popularity of the DP as a result of economic setbacksFootnote 41 and intra-party splitsFootnote 42 accelerated its authoritarian turn. This drift brought about social mobilization within the opposition, especially in the form of student revolts.Footnote 43 When this was backed by secular intellectuals and the bureaucracy, it laid the groundwork for the military intervention in 1960.Footnote 44 After the coup, the army dissolved the DP.

In terms of political regime, the constitution of 1961 following the military intervention in 1960 turned Turkey into a “tutelary democracy.”Footnote 45 From then on, defining itself as “guardian of the regime,”Footnote 46 the military intervened frequently in daily politics and enjoyed autonomy in preparation of the defense budget and deciding on promotions.Footnote 47 Despite these authoritarian traits, however, free elections and the rule of law were respected. As will be discussed, the military tutelage was maintained until the AKP’s “competitive authoritarian turn.”

1961–1980: Polarized pluralism driven by a left–right cleavage

After the coup d’état in May 1960, the new electoral system (D’Hondt) was adopted to obscure the re-emergence of authoritarian one-party rule. This increased fragmentation in the parliament, and thereby polarization.

We call the party system as it was between 1961 and 1980 “polarized pluralism driven by a left–right cleavage.” The left–right cleavage came to the forefront because of social transformation, defined by rapid urbanization, industrialization, and transition to a market economy.Footnote 48 Accordingly, new parties with diverse ideologies took the stage to capture the newly rising sectors of society.Footnote 49

Polarized pluralism has several properties that can be tested in the case of Turkey. First, fragmentation was high, implying that more than five parties shaped the party system, simultaneously and actively.Footnote 50 On this account, between 1960 and 1980, parties of diverse ideological backgrounds, including nationalists (e.g. the MHP), conservatives (e.g. the National Salvation Party (Milli Selamet Partisi, MSP)), socialists (e.g. the Workers Party of Turkey (Türkiye İşçi Partisi, TIP)), and social democrats (e.g. the CHP) found a place in the parliament. This expanded the spatial dimension of party competition.Footnote 51

Second, fragmentation empowered anti-systemic parties.Footnote 52 Although, during the 1970s, almost all parties adopted some sort of anti-systemic rhetoric,Footnote 53 we identify only the TIP as an anti-systemic party. This is mainly because its socialist leaning was regarded as a threat to the regime, which eventually led to its dissolution in 1971. Besides that, the TIP changed the dynamics of competition; that is, its effective opposition in the parliament, for instance, prompted the CHP initially to shift to the “left of center” during the mid-1960s and then to “social democracy” in the next decade.Footnote 54 Finally, it prompted mainstream parties to abandon a “national reminder electoral system” and switch to the less proportional D’Hondt system.Footnote 55 Unlike the TIP, however, despite having heavy nationalist and religious tones in their party programs, we do not regard the MHP and the MSP as anti-systemic parties because they were indispensable parts of coalition governments during the 1970s.

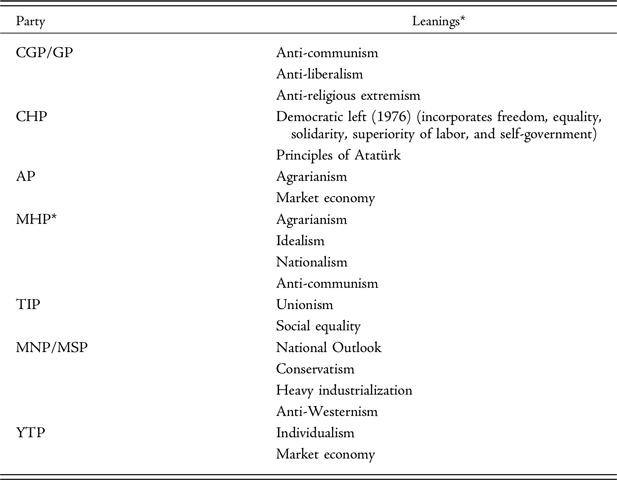

Third, there was a bilateral opposition that made the opposition parties closer to the governing parties than to each other.Footnote 56 This can best be derived from the party programs of the respective parties, which we summarize in Table 3. From the table, for instance, one may infer that the Reliance Party’s (Güven Partisi, GP) emphasis on anti-religious extremism located it against the National Order Party (Milli Nizam Partisi, MNP) tradition that prioritized religious values. In the same vein, the MHP’s emphasis on anti-communism situated itself in opposition to the TIP and later to the CHP, which emphasized trade unionism and social democracy.

Table 3. Parties and leanings (1961–80)

Note: *Based on the party programs, available at (except, MHP 1969):

GP. “Program.” 1967. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/2497

CHP. “Program.” 1976. http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/download/pdf/179310?name=Cumhuriyet%20Halk%20Partisi%20programı

AP. “Program.” 1969. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/754?locale-attribute=en

MHP*. “Election Bulletin, Memleket ve Dünya Hadiseleri.” 1969. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11543/786/197600472_1969.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

TIP. “Program.” 1964. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/628

MNP. “Program.” 1970. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/801

MSP. “Program.” 1976. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/741

YTP. “Program.” 1963. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/2503

Fourth, polarized pluralism empowered minor parties, the independents, and the defectors, which destabilized the party system by stimulating short-term governments:Footnote 57 twenty governments were formed in twenty years. Besides that, polarized pluralism led to the politics of bribery. The Güneş Motel scandal, following the CHP’s failure to form a one-party government, best illustrates this.Footnote 58

What was the role of the opposition in transforming the party system into polarized pluralism? The first thing to note is that the opposition parties, especially the CHP, were unable to generate a stable program during the 1960s. When the CHP achieved that, when Ecevit took office and came up with slogans that addressed the urban poor and peasants, it overtook the Justice Party (Adalet Partisi, AP) as the largest party in the 1973 election and reasserted its dominance in 1977. This shows that when a constructive program is formulated, the opposition may extend its electoral support, which works even better under one-party governments.

In addition, the role of bilateral opposition must be re-emphasized. In a context in which right-wing parties prioritized containing left-wing social mobilization in the street and its repercussions in the electoral field, the MSP and the MHP were strengthened. Because polarization advanced the role of the MSP and the MHP in the coalition talks, these parties further deepened the polarization. In this sense, the MHP’s establishing of armed counter-guerilla camps not only empowered them in coalition bargaining (e.g. it was awarded two ministerial posts in the first National Front government when it had only three deputies), but also led to bloodshed between the opposing camps, which set the stage for the military intervention in 1980.

We should also note that the opposition problem was not only endogenous, but also exogenous to the political parties in question. That is to say, the institutional barriers put up by the establishment restricted the opposition parties’ room to maneuver. In this sense, the regime frequently sanctioned the opposition parties, proclaiming them “anti-regime,” and played the party closure card without hesitation, as in the cases of the MNP and the TIP.

In a nutshell, the combination of institutional barriers and bilateral opposition led the voters, who were disillusioned with the mainstream parties, to either boycott the elections or align with extra-parliamentary groups.Footnote 59 This made forming a stable government a formidable challenge.

1983–2002: Polarized pluralism driven by ethnic and religious cleavage

Polarized pluralism persisted in the aftermath of the coup as well, albeit in altered form as the military crushed left-wing grassroots organizations. In order to reduce fragmentation and thereby polarization, the military regime implemented the D’Hondt system with a record high national (10 percent) and district-level threshold.Footnote 60 Although these measures to stabilize the party system worked well during the 1980s, high levels of fragmentation returned to Turkish politics with the 1991 elections.

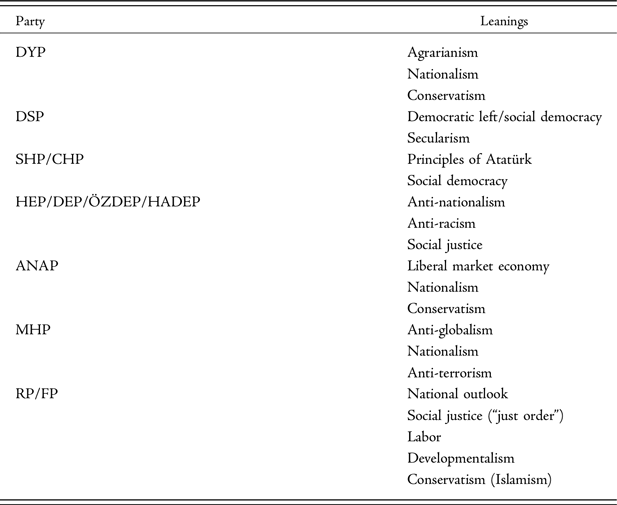

Recall that high levels of fragmentation have systemic implications in the sense of a centrifugal direction for competition. Unlike the class-based polarization of the 1960s and the 1970s, however, polarization during the 1990s was driven by ethnic and religious cleavages.Footnote 61 Ethnic polarization can be grasped simply by looking at the relevant party programs. In this sense, while pro-Kurdish parties’ programs emphasized anti-nationalism and anti-racism, the MHP’s party program was built on anti-terrorism and ultranationalism (see Table 4).

Table 4. Parties and leanings/ideologies (1982–2002)

Note: Based on the party programs, available at:

DYP. “Program.” 1983. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/899

DSP. “Program.” 1991. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/537

SHP. “Program.” 1985. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/handle/11543/567

CHP. “Program, Yeni Hedefler Yeni Türkiye.” 1994. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11543/956/200305414.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

HADEP. “Program.” 1994. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11543/745/199600970.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

ANAP. “Program.” 1983. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11543/693/199607439.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

MHP. “Program.” 2000.

RP. “Program.” 1985. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/650

FP. “Program, Öncü Türkiye için Elele”: Demokrasi İnsan Hak ve Özgürlükleri, Barış, Adalet ve Öncü Bir Türkiye İçin Kalkınma Programı.” 1998. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11543/698/199801418.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

HEP (People’s Labor Party or Halkın Emek Partisi); DEP (Democracy Party or Demokrasi Partisi); ÖZDEP (Freedom and Democracy Party or Özgürlük ve Demokrasi Partisi); HADEP (People’s Democracy Party or Halkın Demokrasi Partisi); FP (Virtue Party or Fazilet Partisi).

Concerning polarization along religious lines, the forerunner on the Islamic front was the Welfare Party (Refah Partisi, RP). From the outset, the RP constantly labeled itself the “anti-order” (or “anti-establishment”) party and referred to others as “order parties.” This rhetoric hindered it from joining coalition governments after the 1991 elections. Therefore, we identify the RP between 1991 and 1995 as an anti-systemic party. Contrary to that, although the RP intensified its Islamic tone and injected its Islamic agenda into official documents, such as “Just Order,” it formed an eleven-month-long government with the True Path Party (Doğru Yol Partisi, DYP) under the premiership of Erbakan, following its victory in the 1995 elections. Therefore, considering its coalition potential, we no longer qualify the RP as an anti-systemic party.

Moreover, bilateral opposition was a prevalent feature of polarized pluralism. To illustrate this, the social democrats, whose main political pillar was secularism, confronted RP rule. Bilateral opposition was evident among right-wing parties as well. To illustrate this, despite having similar party programs and bases of support,Footnote 62 the Motherland Party (Anavatan Partisi, ANAP) and the DYP failed to form a coalition government after the 1995 elections because of their leaders’ personal animosity. Accordingly, the DYP formed a government with the RP in June 1996, which set the stage for the so-called “postmodern coup” in February 1997Footnote 63 and AKP rule in 2002.

Last but not least, as a result of polarized pluralism, these governments were short-lived: ten governments were formed between 1991 and 2002, which rendered the mainstream parties largely unresponsive to voters’ demands.

What was the role of the opposition in the emergence of polarized pluralism in this period? The first thing to note is that almost all parties represented in the parliament found a place in the coalition governments. The result was twofold. First, the opposition parties did not seek to address voters with a comprehensive program. More importantly, the “politics of outbidding” prevailed,Footnote 64 which implies that the parties in power became unresponsive to voters’ demands. As a result, economic crises and political instability became an indispensable part of Turkish politics during the 1990s and early 2000s.Footnote 65 Second, bilateral opposition became pervasive. However, this time it was quite different from the 1970s. That is to say, while the 1970s witnessed polarization among left–right camps and, apart from the MSP, no party was able to form a government with the members of both camps, bilateral opposition was at stake within the same camp (e.g. between the DYP and ANAP) during the 1990s. In this context, as the DYP–SHP (Sosyal Demokrat Halkçı Parti, Social Democratic Populist Party) or DSP–MHP–ANAPFootnote 66 coalitions demonstrate, it was much more feasible to form a government with adherents of differing ideologies. Fragmentation on the right thus permeated the left.Footnote 67 Accordingly, social democrat votes were divided among the DSP, CHP, and SHP. Such fragmentation led to the defeat of social democrat candidates in İstanbul and Ankara by the RP in the 1994 local elections by a small margin. Third, the sword of Damocles still hung over the parties. The critical junctures were the closures of the pro-Kurdish parties and the Islamic-leaning parties by the Constitutional Court, which had severe implications in the political realm: first of all, the result was the escalation of the armed struggle with the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party or Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê), while secondly the public reaction brought the AKP to power.

High levels of fragmentation during the 1990s triggered the military memorandum in 1997 because of the high polarization this induced. When polarization was combined with economic and political mismanagement, the view that coalitions are malignant found a large audience. This political turn—the supremacy of stability over pluralism—constituted the “psychological dimension” of entering into the longest period of one-party government.

2002–today: Predominant party system with a leaning toward a hegemonic party system

With the support of the electoral system, the AKP captured two-thirds of the seats in the 2002 elections despite winning only one-third of the votes. After winning the third election in a row by at least a 10 percent margin, the AKP transformed the Turkish party system into a predominant party system in the 2011 elections.Footnote 68

During AKP rule, electoral volatility and fragmentation declined sharply, and the party system stabilized.Footnote 69 Despite these developments, polarization soared. Comparative Study of Electoral Systems data, for instance, show that Turkey’s party system polarization score rose from 2.34 in 2002 to 6.21 in 2015.Footnote 70 Similarly, a survey conducted by Konda in April 2010 reveals the intensity of polarization along party lines.Footnote 71 Even more dramatically, partisan polarization extends to the ethnic and religious sphere. Accordingly, as research done by BILGESAMFootnote 72 and İstanbul Bilgi UniversityFootnote 73 revealed, ethnic and religious polarization deepened along with partisan polarization.

With regard to the role of the opposition parties in party system change, an overview suggests that if one excludes the temporary cooperation between the MHP and the CHP during the 2010 referendum, the presidential elections in 2014, and the cooperation between the CHP and the People’s Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi, HDP) against the introduction of presidentialism in Turkey, the opposition was unable to open a unique front against the AKP. Instead, bilateral opposition prevailed among the opposition parties, particularly between the nationalist MHP and the pro-Kurdish parties, which is crystallized better in their party programs (see Table 5). Unlike in the 1990s, however, the contestation between these poles took place in parliament, at least from 2007 onwards.

Table 5. Parties and leanings/ideologies (2002–15)

Note: Based on the party programs, available at:

CHP. “Program, Yeni Hedefler Yeni Türkiye.” 2004. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/bitstream/handle/11543/963/200402098.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

AKP. “Program, Kalkınma ve Demokratikleşme Programı.” 2002. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/handle/11543/926

MHP. “Program, Geleceğe Doğru.” 2009. https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/handle/11543/923?locale-attribute=en

HDP. “Program, Emek, Eşitlik, Özgürlük, Barış ve Adalet İçin.” 2014. https://www.hdp.org.tr/tr/parti/parti-programi/8

DEHAP (Democratic People’s Party or Demokratik Halk Partisi).

Bilateral opposition also had systemic implications: it prolonged AKP rule. The turning point was the coalition talks among the opposition leaders following the AKP’s loss of its parliamentary majority in the June 2015 elections. After the elections, MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli immediately declared that the party would not take part in any coalition that included the HDP. This development ruled out the possibility of a coalition government from the start.

In addition to bilateral opposition, this term witnessed no entry of new parties to the parliament. That is to say, apart from the parties that represent the main cleavages in Turkish society (religious and ethnic), no other party managed to pass the electoral threshold. This secured the place of the parliamentary parties in the political system without formulating any alternative program and taking any political responsibility.

The opposition suffered from other weaknesses as well. Above all, the fragmented opposition lacked any cross-class support that might jeopardize the AKP’s grip on power.Footnote 74 Similarly, the opposition suffered from a lack of unity within the party. For instance, the CHP experienced intense intra-party rivalry between a defensive nationalist camp and the European-style social democratic faction.Footnote 75 Besides that, the opposition parties failed to attract new voters, with their party program emphasizing redistribution and anti-corruption.Footnote 76

The opposition was further weakened by the policies adopted by the AKP government. First, the government crushed both parliamentary and extra-parliamentary opposition through judicial investigations, including Ergenekon and KCK. In the same vein, the AKP weakened the opposition by co-opting their leaders. Most notably, the AKP eroded the “People’s Voice Party” (HAS Parti) and the DP by persuading their leaders to defect in return for high-ranking positions within AKP cadres.Footnote 77 The adoption of such tactics—miniaturizing its clientelist policies—further entrenched the AKP’s electoral dominance.

These vulnerabilities on the part of the opposition parties led the opposition to use non-parliamentary channels to confront the incumbent. Mass demonstrations in favor of secularism in 2007 and the Gezi Park protests in 2013 best illustrate this. Despite their prevalence, however, the street protests were not long lasting as the government tightened its control over both the security and the judicial apparatus. Besides that, the widespread belief that the AKP would again play the “victim” deterred the opposition from street protests. In addition to the mass protests, the AKP was also confronted by a military memorandum in 2007Footnote 78 and the threat of party closure in 2008.Footnote 79

As institutional measures and street mobilization failed to break AKP rule, the opposition parties concentrated their efforts on developing a strong political program. The electoral pledges of the CHP, including “Family Insurance” and a “Bonus for Retirees,” were the products of this policy. At the same time, the opposition lessened its emphasis on “secularism” and adopted the principle of “justice” as its main policy line. CHP’s “March for Justice” in 2017 illustrates this policy shift. This change in political strategy enabled the CHP to transcend the ideological deadlock and extend its room to maneuver beyond niche constituencies. The CHP’s success in the March 2019 local elections can be seen from this perspective.

Before closing this section, we must contend, along with other scholars,Footnote 80 that the predominant party system in Turkey may collapse into a hegemonic party system if the political situation persists in the short term. First of all, the AKP’s efforts to avoid sharing power with the opposition after the June 2015 elections and the declaration of a “state of emergency” following the failed coup attempt in July 2016, restrained political freedom and competition through the securitization of dissent.Footnote 81 Second, the use of fraud has become more evident. The recent violations of vote counting in the presidential referendum in April 2017 and the voting conditions in the eastern and southeastern provinces draw particular attention to electoral malpractice. Similarly, the repression of the opposition became overt, as in the case of the Gezi Park protests.Footnote 82

Although these features bring the party system closer to a hegemonic party system, in order to fully qualify as a hegemonic party system two more features must be observed. The first is related to the AKP’s parliamentary majority. Unlike in a hegemonic party system, the AKP has not been able to obtain enough of a majority (two-thirds of the seats) to change the constitution unilaterally. Second, unlike a hegemonic party system, the opposition parties are not wholly “satellite parties.”

The transition to a hegemonic party system indicates that Turkey’s regime has been evolving into a “competitive authoritarian regime,”Footnote 83 as defined by Levitsky and Way.Footnote 84 In the case of the AKP, the drift toward competitive authoritarianism means that the essentials of democracies—such as the separation of powers, press freedom, and the procedural requirement of conducting elections—are no longer met, and political competition is skewed in favor of the incumbent party through repression, fraud, and patronage.Footnote 85 A notable example that shows how political competition has been narrowed down was the imprisonment of HDP leader Selahattin Demirtaş, along with other deputies, following the removal of immunities by parliamentary vote in May 2016. In the same vein, the threat of imprisonmentFootnote 86 made to IYI (Good Party or IYI Parti) party leader Meral Akşener illustrates how the pressure on the opposition has been tightened.

Conclusion

This paper seeks to highlight the changing nature of the Turkish party system, based on Sartori’s party system typology, which incorporates the number of parties and the spatial distance between them in its analysis. In this way it attempts to update the literature, which suffers from the fact that it covers only a limited time period and has an inconsistent theoretical framework.

Despite having one-party governments for more than half of its parliamentary experience, the trajectories of the Turkish party system reveal that it is dynamic, moving from one party system type to another, under the shadow of military tutelage. Accordingly, the three main maladies of the Turkish party system—namely fragmentation, volatility, and polarization—have persisted as defining features of Turkish politics.

Drawing on Sartori’s framework, we call the party system from 1923 to 1950 “one-party authoritarianism,” which ended with the start of DP rule in 1950. The party system under DP governments showed the characteristics of a “predominant party system” until 1957 and then transformed into a “hegemonic party system,” with the efforts of the DP to eliminate parliamentary opposition. In the post-1960 period, the party system was “polarized pluralism driven by class cleavage,” characterized by violent contestation between the rising left and the right. In the post-1980 period, polarization persisted, but this time it was driven by ethnic and religious conflict. Ultimately, fragmentation and polarization along religious lines triggered the military memorandum in 1997. When these developments were combined with the political and economic instability under coalition governments, it laid the ground for the establishment of the longest single-party rule in Turkey. Similar to the DP, the AKP’s authoritarian turn started after its third election victory and intensified with the transition to the “a la Turca” presidential system in 2017.

In light of the historical evolution of the Turkish party system, our analysis reveals that fragmented opposition generates polarization, which then leads to one-party governments as the masses vote for the largest party to prevent the opposition camp from holding on to power (e.g. in the 1960s). Fragmented opposition also leads to military intervention, as occurred during the 1970s. On the other hand, bilateral opposition is more salient in the context of one-party government. It typically leads to failure of the opposition to coordinate against the incumbent, thus prolonging one-party government, as occurred in the aftermath of the June 2015 elections.

As illustrated in this paper, the implications of party system change for regime change need to be discussed. On that matter, we have argued that the military intervention in 1960 marked the start of military tutelage in Turkey. Military tutelage was transformed into “competitive authoritarianism” in the aftermath of the failed coup attempt in July 2016, which blurred the line between the party and the state.

In a context in which electoral misconduct, repression of dissidents, clientelism, and control over the media have become rampant, the opposition has less chance to confront the incumbent. Thus, we anticipate that alternation in power will possibly occur due to the government’s failures (e.g. economic turmoil) or intra-party splits. The results of the local elections in March 2019 are the clearest indication of this trend.

Finally, considering this paper as a preliminary attempt to reframe and renew the literature, there is no doubt that more systematic research is required to advance our knowledge of party system change and the role of the opposition in Turkey. First, while this study is based on Sartori’s typology, party system change analysis based on typologies by other leading authors, such as BlondelFootnote 87 and Rokkan,Footnote 88 would be welcome. Second, to our knowledge no study situates Turkey’s party system experience in a cross-national perspective in an effort to understand its peculiarities and similarities with other cases, be they in the Middle East or Europe.