Introduction

Scleractinian corals of Maastrichtian age have been the focus of various studies since the late 18th century, including works on their taxonomy (e.g. Faujas-Saint-Fond, Reference Faujas-Saint-Fond1798–1803; Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826–1844; Milne Edwards & Haime, Reference Milne Edwards and Haime1857; Nötling, Reference Nötling1897; Trauth, Reference Trauth1911; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich1917; Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925; Wells, Reference Wells1933, Reference Wells1934; Alloiteau, Reference Alloiteau1936, Reference Alloiteau1952b, Reference Alloiteau1958; Kuzmicheva, Reference Kuzmicheva1985, Reference Kuzmicheva1987; Tchéchmédjiéva, Reference Tchéchmédjiéva1986, Reference Tchéchmédjiéva1995; Filkorn, Reference Filkorn1994; Leloux, Reference Leloux1999, Reference Leloux2004; Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2000, Reference Baron-Szabo2002, Reference Baron-Szabo2006, Reference Baron-Szabo2008; Filkorn et al., Reference Filkorn, Avendano-Gil, Coutiño-José and Vega-Vera2005; Jell et al., Reference Jell, Cook and Jell2011; Löser, Reference Löser2012; Baron-Szabo et al., Reference Baron-Szabo, Schlagintweit and Rashidi2023) as well as in analyses primarily dealing with Maastrichtian stratigraphy and sedimentology (e.g. Gill et al., Reference Gill, Cobban and Kier1966; Sohl & Koch, Reference Sohl and Koch1984; Görmüş et al., Reference Görmüş, Demircan, Kadioğlu, Yağmurlu and Us2019; Afghah, Reference Afghah2022). Frequently, corals have been documented from rudist-dominated limestones (e.g. Kühn, Reference Kühn1933; Özer, Reference Özer1992; Pons et al., Reference Pons, Gallemí, Höfling and Moussavian1994; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2002; Schafhauser et al., Reference Schafhauser, Götz, Baron-Szabo and Stinnesbeck2003; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Stemann, Blissett, Brown, Ebanks, Gunter, Miller, D., Pearson, Wilson and Young2004; Khazaei et al., Reference Khazaei, Yazdi and Löser2009). In more recent decades, an increasing number of works have been aimed at assessments of extinction patterns amongst corals across the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) boundary (Rosen & Turnšek, Reference Rosen and Turnšek1989; Kiessling & Baron-Szabo, Reference Kiessling and Baron-Szabo2004; Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2006, Reference Baron-Szabo2008).

The purpose of the present paper is to provide a comprehensive overview of Maastrichtian occurrences of scleractinian corals and evaluate their taxonomic assignment, palaeoecological occurrences and palaeogeographical distribution (Tables 1–5).

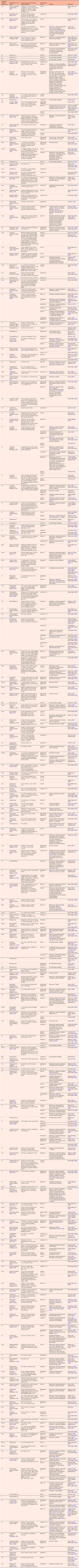

Table 1. List of Maastrichtian scleractinian coral genera and their family assignments; *previously (**potentially previously) established microstructural group

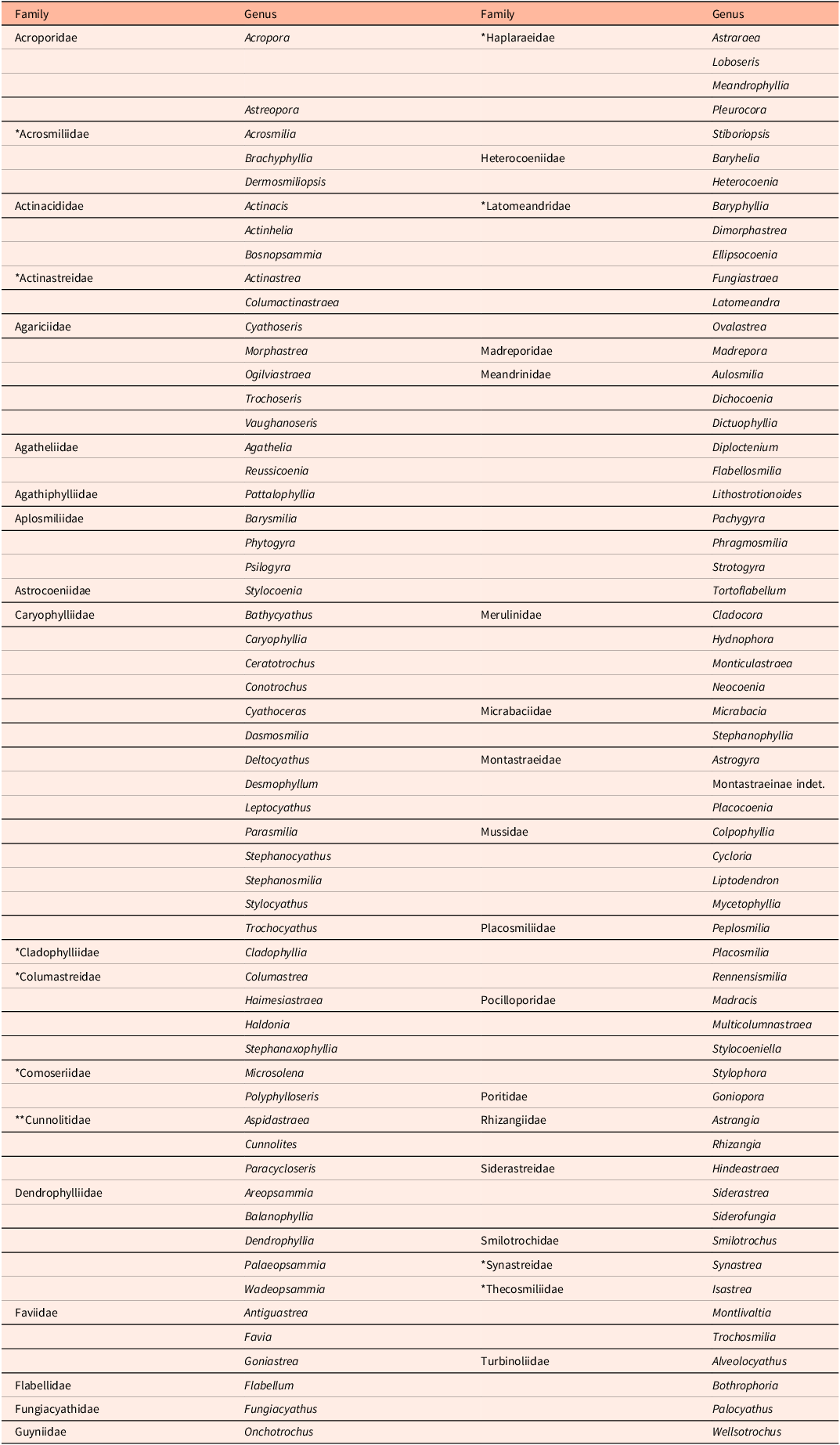

Table 2. Corallite size and types of corallite integration of the Maastrichtian scleractinian coral species; 186 taxa have been included in our evaluation (19 species were omitted due to a lack of sufficient data). Corallite sizes: small (s) = up to 2.5 mm; medium (m) = >2.5–9 mm; large (l) = >9 mm. For information on individual species, reference is made to Table 4

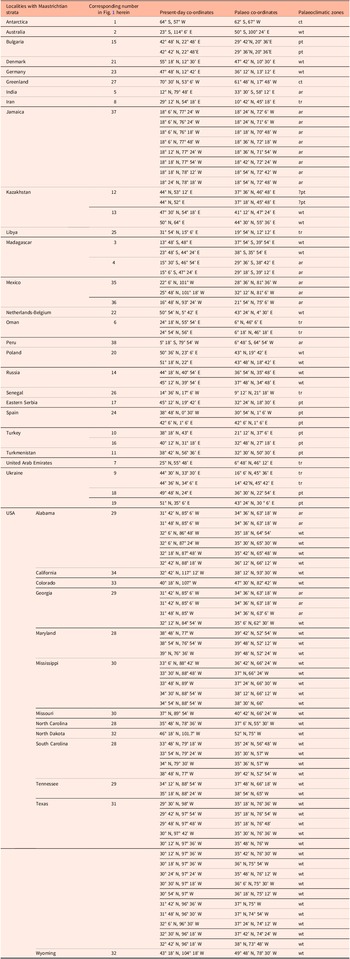

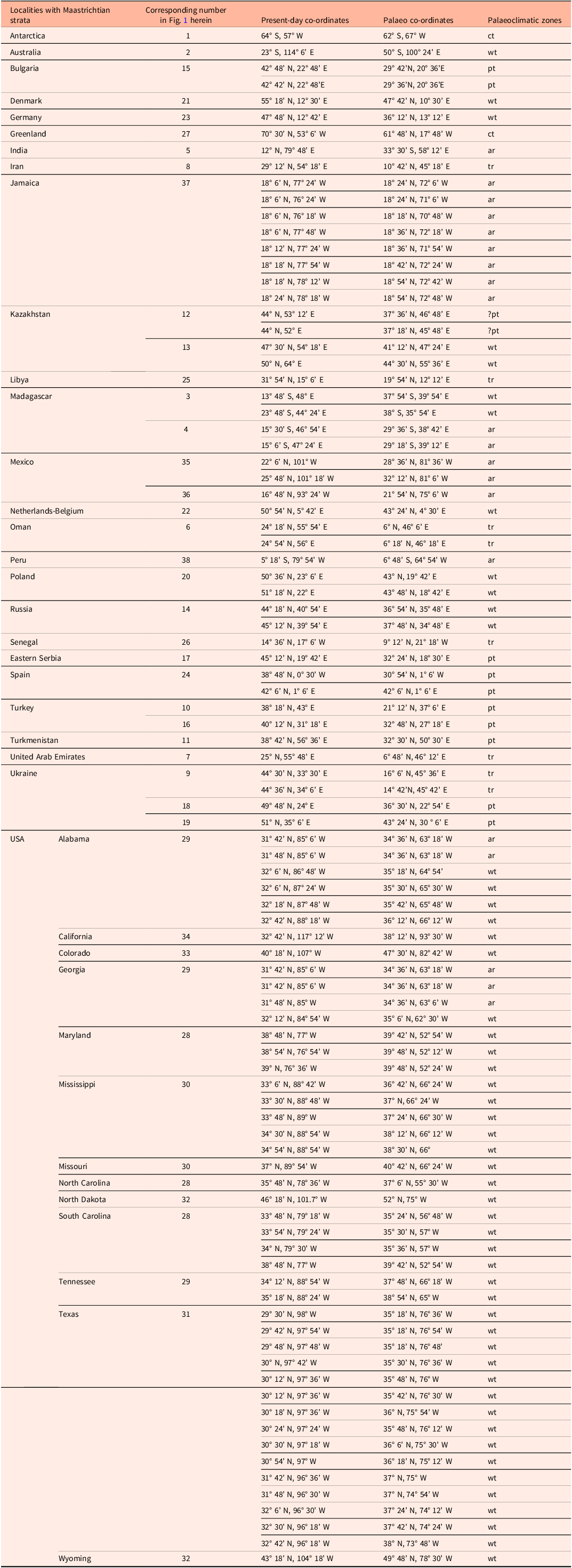

Table 3. List of localities with Maastrichtian strata from which the coral material has been collected. Co-ordinates and palaeo co-ordinates representative of distributional patterns are from Paleobiology Database (see paleobiodb.org, for more details on individual sites); palaeoclimate zones estimated based on paleomaps by Tennant et al. (Reference Tennant, Mannion, Upchurch, Sutton and Price2017) and the Paleomap project at www.scotese.com: (ar) = arid; (ct) = cool temperate; (pt) = para- to subtropical; (tr) = tropical; (wt) = warm temperate

Table 4. Alphabetical list of Maastrichtian scleractinian coral species, localities from which they were collected and remarks on their taxonomic position. Age of strata at collecting site: (*) = Maastrichtian (unspecified); (1) = lower Maastrichtian; (2) = mid-Maastrichtian; (3) = upper Maastrichtian (for more details on locations and recent taxonomic updates, see Paleobiology Database [paleobiodb.org]). For further information on localities, see also Table 3, and for excluded taxa herein, reference is made to Baron-Szabo (Reference Baron-Szabo2006, Reference Baron-Szabo2008) and updates herein. Types of corallite integration are as follows: cp = cerioid-plocoid; s = solitary (no integration); htm = hydno-thamnasterioid-meandroid; b = branching. Corallite sizes: small (s) = up to 2.5 mm; medium (m) = >2.5–9 mm; large (l) = >9 mm. * = might occur in more than one type of corallite integration or overlapping types of integration

Table 5. List of localities with Maastrichtian strata from which the coral material was collected, number of species (colonial/solitary), and palaeoenvironment recorded for each area (*palaeoecological data retrieved from original publications with updates provided by Paleobiology Database [paleobiodb.org]). For co-ordinates/palaeo co-ordinates of localities, see Table 3

Material and methods

Material included in the present study originates from beds having stratigraphical ranges clearly defined as Maastrichtian, only including works in which descriptions or illustrations of the coral material were provided. Works in which the stratigraphical ranges of the coral-bearing strata are not distinctly defined but given as, for example, Campanian–Maastrichtian (e.g. Felix, Reference Felix1906; Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2000; Gameil, Reference Gameil2005), or in which material was either only listed or insufficiently described (e.g. Böhm. Reference Böhm1891; Rengarten, Reference Rengarten1959) and identifications have not been confirmed in subsequent works, are excluded from the present study. Over 2,000 records, including around 500 nominal taxa, have been evaluated (Kiessling & Baron-Szabo, Reference Kiessling and Baron-Szabo2004; Leloux, Reference Leloux2004; Filkorn et al., Reference Filkorn, Avendano-Gil, Coutiño-José and Vega-Vera2005; Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2006, Reference Baron-Szabo2008; Khazaei et al., Reference Khazaei, Yazdi and Löser2009; Jell et al., Reference Jell, Cook and Jell2011; Löser, Reference Löser2012; Görmüş et al., Reference Görmüş, Demircan, Kadioğlu, Yağmurlu and Us2019; Baron-Szabo et al., Reference Baron-Szabo, Schlagintweit and Rashidi2023), inclusive of new information provided by Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org). Affinities of coral assemblages have been calculated using the Jaccard Index.

Abbreviations used in Table 4 are as follows: d = corallite diameter; d (series) = width of corallite series; cc = distance between corallite centres; h = height of corallum; s = number of septa; s/mm = septal density.

Material illustrated (Figs. 2–9) in the present paper includes specimens from the following institutions:

Figure 1. Palaeomap showing localities with Maastrichtian coral faunas included in the present study. 1 = Antarctica; 2 = Australia; 3–4 = Madagascar; 5 = India; 6 = Oman; 7 = UAE; 8 = Iran; 9 = Ukraine; 10 = Türkiye; 11 = Turkmenistan; 12–13 = Kazakhstan; 14 = Russia; 15 = Bulgaria; 16 = Türkiye; 17 = eastern Serbia; 18–19 = Ukraine; 20 = Poland; 21 = Denmark; 22 = the Netherlands-Belgium; 23 = Germany; 24 = Spain; 25 = Libya; 26 = Senegal; 27 = Greenland; 28–34 = USA; 35–36 = Mexico; 37 = Jamaica; 38 = Peru. Palaeomap modified from Paleomap project (Scotese, Reference Scotese2014; www.scotese.com). For palaeo co-ordinates, see Table 3.

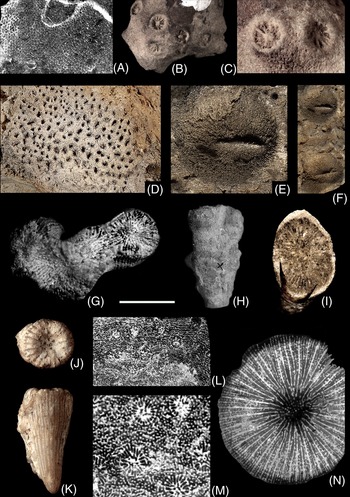

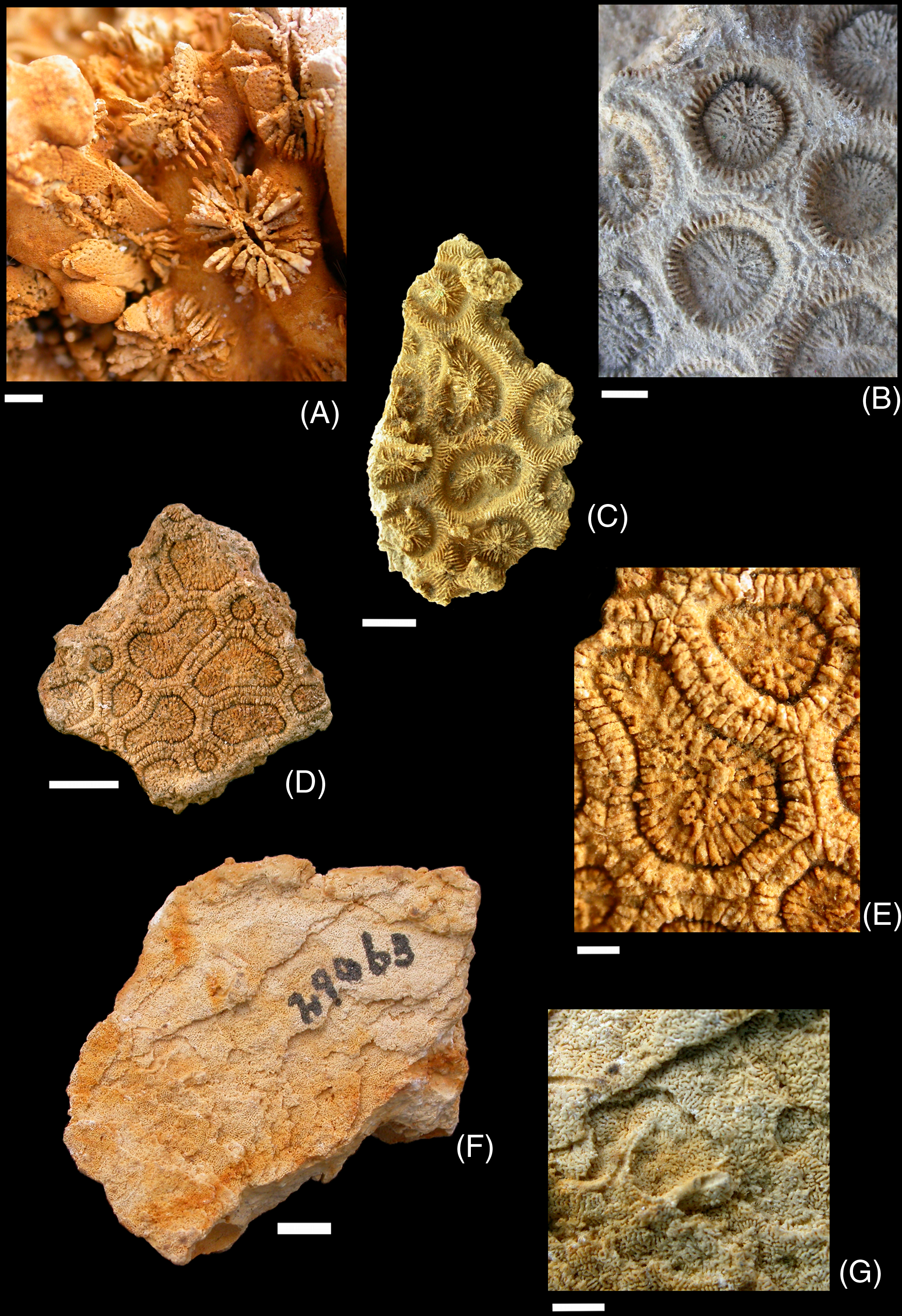

Figure 2. Maastrichtian scleractinian corals from localities in the Netherlands-Belgium, Jamaica, Senegal and Madagascar (*denoting images derived from http://colhelper.mnhn.fr, by permission of Dr Sylvain Charbonnier, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, August 2020). (A) Actinastrea goldfussi (d’Orbigny, Reference Orbigny1850) (MB.K 3742), upper Maastrichtian, southern Limburg, the Netherlands; upper surface of colony, corallite view, contrast inverted, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 22 mm). (B) *Dendrophyllia sp. (MNHN.F.R10840), Maastrichtian, Popenguine, Senegal; upper surface of colony, corallite view (scale bar equals 7 mm). (C) *Dendrophyllia sp. (MNHN.F.R10840), Maastrichtian, Popenguine, Senegal; upper surface of colony, close-up view of corallites (scale bar equals 3.5 mm). (D) Actinhelia elegans (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (MB.K 3688); upper Maastrichtian, southern Limburg, the Netherlands; upper surface of colony, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 13.5 mm). (E) Cunnolites polymorphus (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (MB.K3103); upper Maastrichtian, southern Limburg, the Netherlands; close-up of Fig. 2F (scale bar equals 14 mm). (F) Cunnolites polymorphus (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (MB.K 3103); upper Maastrichtian, southern Limburg, the Netherlands; upper surface, corallite view, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 35 mm). (G) Latomeandra boltonae (Wells, Reference Wells1934) (holotype, USNM I 74479), upper Maastrichtian, Catapudensis, Jamaica; upper surface of colony, corallite view (scale bar equals 11.5 mm). (H) Latomeandra boltonae (Wells, Reference Wells1934) (holotype, USNM I 74479), upper Maastrichtian, Catapudensis, Jamaica; upper surface of colony, lateral view (scale bar equals 45 mm). (I) *Balanophyllia caulifera (Conrad, Reference Conrad1848), holotype of Palaeopsammia mitsinjoensis (Alloiteau, Reference Alloiteau1958) (MNHN.F.J08195); Maastrichtian, Mitsinjo, Madagascar; corallite view of corallum, polished (scale bar equals 7.5 mm). (J, K) *Stephanosmilia madagascariensis (Alloiteau, Reference Alloiteau1958) (MNHN.F.M05336); Maastrichtian, Popenguine, Senegal; (J) upper surface of corallum, corallite view, (K) lateral view (scale bar equals 3 mm). (L, M) Actinacis reussi (Oppenheim, Reference Oppenheim1930) (USNM field number 363); Titanosarcolites Limestone, Maastrichtian, Jerusalem Mountain Inlier, Parish of Hanover; Jamaica; (L) corallite view of colony, thin section (scale bar equals 5 mm), (M). close-up of Fig. 1K (scale bar equals 2.5 mm). (N) Paracycloseris nariensis (Duncan, Reference Duncan1880) (USNM field number 557a); upper Maastrichtian, Rio Minho, Jamaica; corallite view of corallum, thin section (scale bar equals 4 mm).

Figure 3. Maastrichtian solitary corals from the Maastrichtian type area (the Netherlands-Belgium). (A, B) Caryophyllia konincki (Milne Edwards & Haime, Reference Milne Edwards and Haime1848a) (NHMM RH 204), upper Maastrichtian, Meerssen Member, Maastricht Formation, Eben Emael (Marnebel quarry complex), northeast Belgium (scale bar equals 2 mm). (C) Trochosmilia faujasi Milne Edwards & Haime, Reference Milne Edwards and Haime1848c (RGM.29137), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation, lateral view (scale bar equals 10 mm). (D, E) Peplosmilia latona (Felix, Reference Felix1903) (RGM.29036, leg. J.H.F. Umbgrove); lectotype of Placosmilia robusta (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (F, G) Areopsammia alacca (Morren, Reference Morren1828) (RGM 841362, formerly RGM 212452, ex Leloux Collection, Jx. 903), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, upper Nekum or lower Meerssen members, western side of former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation, lateral view (scale bar equals 10 mm). (H, I) Montlivaltia angusticostata (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925) (RGM.29142, leg. J.H.F. Umbgrove), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, ‘Houthemerberg, Vilt’; mouldic preservation, basal and lateral view (scale bar equals 5 mm).

Figure 4. Maastrichtian solitary corals from the Maastrichtian type area (the Netherlands-Belgium). (A–C) Parasmilia centralis (Mantell, Reference Mantell1822) (RGM 841366, formerly RGM 212465, leg. Kit Liem Oen) upper lower Maastrichtian, Gulpen Formation, Vijlen Member, CBR-Lixhe quarry; lateral, top and basal view (scale bars equal 10 (A) and 2 mm (B, C)). (D) Diploctenium cordatum (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.212454.a), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, top Nekum Member, western side of former ENCI Quarry; lateral view, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 5 mm). (E) Diploctenium pluma (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.29135, STA.8167, leg. Thierens, 1857), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; lateral view, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (F) Cunnolites cancellata (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM 841354, formerly RGM 212454.b, ex Leloux Collection, Jx 1022), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, top Nekum Member Member to base of Meerssen Member, Maastricht (former ENCI Quarry); top view, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (G) Cunnolites cancellata (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.33844), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm).

Figure 5. Maastrichtian colonial scleractinians from localities in the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage (the Netherlands-Belgium). (A) Actinastrea goldfussi (d’Orbigny, Reference Orbigny1850) (RGM.841363, formerly RGM.212459, ex Leloux Collection, Jx.2120), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf -4/-5), Maastricht (former ENCI Quarry); mouldic preservation, corallites with predominantly 6-6 septal pattern (scale bar equals 2 mm). (B) Actinastrea goldfussi (d’Orbigny, Reference Orbigny1850) (RGM.29070), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; recrystallised skeletal preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (C) Actinastrea goldfussi forma faujasi (Milne Edwards & Haime, Reference Milne Edwards and Haime1857) (RGM.841360.a, formerly RGM.212458.a, ex Leloux Collection, Jx.2115), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf-4/-5), Maastricht (former ENCI quarry); corallites with predominantly 8-8 septal pattern, basal view, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (D) Aplosastrea geminata (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826), lectotype (IPB GOLDFUSS 233a) designated by Löser (Reference Löser2011); Sint-Pietersberg area, Maastricht. Recrystallised skeletal or cast preservation (scale bar equals 5 mm). (E) Columactinastraea fallax (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925), lectotype (RGM.29074), Maastricht Formation, South Limburg; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (F, G) Columnactinastrea anthonii (Leloux, Reference Leloux2003), holotype (RGM.216001, ex Leloux Collection), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member, basal IVf-4, former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm); recrystallised skeletal preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (H) ?Isastrea angulosa (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (THDN.2438, now at Naturalis, Leiden), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, southern Limburg; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 5 mm).

Figure 6. Maastrichtian colonial scleractinians from localities in the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage (the Netherlands-Belgium). (A) Montipora cretacea (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925), holotype (RGM.29072), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Maastricht area, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (B) Neocoenia (Placocaeniopsis) rotula (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.841361, formerly RGM.212455, ex Leloux Collection, Jx.1188), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf-3/-4), former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation, basal view (scale bar equals 5 mm). (C) Pleurocora arachnoides (Walch, Reference Walch1775) forma minor (Quenstedt, Reference Quenstedt1881) (RGM.72658, leg. J.H.F. Umbgrove), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, southern Limburg; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (D) Pleurocora arachnoides (Walch, Reference Walch1775) (RGM.76612, leg. J.H.F. Umbgrove), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, southern Limburg ove; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (E) Pleurocora arachnoides (Walch, Reference Walch1775) forma conica (Umbgrove), lectotype (RGM.29037), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Maastricht area; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (F) Heliastrea francqana H. (Milne Edwards & Haime, Reference Milne Edwards and Haime1857), grouped herein with Placocoenia macrophthalma (RGM.841352, formerly RGM.212451, ex Leloux Collection, Jx.2144), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf-4/-5), former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (G) Placocoenia macrophthalma (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM 29044, probably Staring Collection no. 14198), southern Limburg; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (H) Baryphyllia maxima (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925), holotype; RGM.29030, ‘Maastricht’; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm).

Figure 7. Maastrichtian colonial scleractinians from localities in the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage (the Netherlands-Belgium). (A) Placocoenia macrophthalma (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826); NHMM K.552, Blom Quarry, Meerssen Member IVf-3 to IVf-5, Maastricht Formation, upper Maastrichtian; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (B) Ellipsocoenia conferta (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925), holotype; RGM.29039, ‘Maastricht’, Maastricht Formation; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 mm). (C) Ellipsocoenia conferta (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925), formerly Favia maastrichtensis (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925); Collection Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen no. 1227, now at Naturalis, Leiden; Keerderberg, southern Limburg; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 5 mm). (D, E) Favia planissima (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925), holotype, subjective junior synonym of Dictuophyllia reticulata (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.20940), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm) and detail (E, scale bar equals 2 mm). (F, G) Meandrophyllia velamentosa (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826), formerly Meandrophyllia gyrosa (Goldfuss, 1825) (RGM.29063), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation; overview and detail, respectively (scale bars equals 5 and 2 mm, respectively).

Figure 8. Maastrichtian colonial scleractinians from localities in the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage (the Netherlands-Belgium). (A) Aspidastraea clathrata (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.29101), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, southern Limburg; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (B) Dimorphastrea solida (Umbgrove, Reference Umbgrove1925) (RGM.841365, formerly RGM.212457, ex Leloux Collection, Jx. 1646), upper Maastrichtian, Meerssen Member (IVf-4/-5) former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 5 mm). (C, D) Synastrea geometrica (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.14054), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation, overview and detail, respectively (scale bar equals 10 and 2 mm, respectively). (E, F) Morphastrea escharoides (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.33826), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 and 2 mm, respectively). (G, H) Fungiastraea flexuosa (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.76625, leg. J.H.F Umbgrove, December 8, 1918), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area (Lichtenberg); mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 2 and 10 mm, respectively). (I, J) Meandrophyllia velamentosa (Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826) (RGM.29050), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member inferred, Sint-Pietersberg area; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 and 2 mm, respectively).

Figure 9. Maastrichtian colonial scleractinians from localities in the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage (the Netherlands-Belgium). (A) Heterocoenia grandis (Reuss, Reference Reuss1854) (RGM.841350, formerly RGM.212448), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member, former ENCI Quarry, Meerssen Member, Maastricht Formation, upper Maastrichtian; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (B) Heterocoenia gracilis (Quenstedt, Reference Quenstedt1881) (RGM.841358, formerly RGM.212453, ex Leloux Collection, Jx.1122), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf-4\-5), former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (C, D) Heterocoenia grandis (Reuss, Reference Reuss1854) (RGM.841364, formerly RGM.212450), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf-4), former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation, lateral view (scale bar equals 5 mm) and basal view (scale bar equals 2 mm). (E) Heterocoenia gracilis (Quenstedt, Reference Quenstedt1881) (RGM 841351, formerly RGM.212456), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf-3/-4), former ENCI Quarry; mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm). (F) Heterocoenia grandis (Reuss, Reference Reuss1854) with bioerosional trace fossil (NHMM K 548), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member, southern Limburg; basal view, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 5 mm). (G) Heterocoenia? sp. (sensu Goldfuss, Reference Goldfuss1826), cf. ‘Bacillastraea’ sensu Umbgrove (Reference Umbgrove1925, pl. 11, Fig. 22) (NHMM JJ 11287), upper Maastrichtian, Maastricht Formation, Meerssen Member (IVf-4), former ENCI Quarry; lateral and basal view of ‘corallite’, mouldic preservation (scale bar equals 10 mm).

MB, Museum für Naturkunde der Humboldt Universität, Berlin, Germany;

MNHN, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France;

NHMM, Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht, the Netherlands;

RGM, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, the Netherlands;

USNM, United States National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, USA (now NMNH).

The taxonomic framework used here follows a synthesis of the modern studies (for a discussion, see Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2021b) with the classic works by Milne Edwards & Haime (Reference Milne Edwards and Haime1857), de Fromentel (Reference Fromentel1861, Reference Fromentel and d’Orbigny1877), Duncan (Reference Duncan1884), Koby (Reference Koby1887), Ogilvie (Reference Ogilvie1897), Oppenheim (Reference Oppenheim1930), Vaughan & Wells (Reference Vaughan and Wells1943), Alloiteau (Reference Alloiteau and Piveteau1952a, Reference Alloiteau1958) and Wells (Reference Wells and Moore1956) and recent updates (Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2021a, b and present study). For information on excluded taxonomic models, reference is made to Baron-Szabo (Reference Baron-Szabo2021a, pp. 29, 30, 166; Reference Baron-Szabo2021b, pp. 391, 392).

Analyses and results

Overview of localities with coral-bearing Maastrichtian strata

Africa: Libya, Madagascar, Senegal

Maastrichtian coral faunas from Africa are rather rare and distinctly dominated by solitary forms (80.7%) (see Table 5), as recorded in older studies carried out on corals from Libya by Rossi Ronchetti (Reference Rossi Ronchetti1955), and coral assemblages found in West African and sub-Saharan areas by Alloiteau (Reference Alloiteau1952b [Senegal]; Reference Alloiteau1936, Reference Alloiteau and Collignon1951, Reference Alloiteau1958 [Madagascar]) (Table 4). Unfortunately, little information on the lithology of the coral-bearing rocks was provided in these works, and no bioconstructions formed by the corals were reported. In recent papers, coral faunas have been re-evaluated and thoroughly revised (Kiessling & Baron-Szabo, Reference Kiessling and Baron-Szabo2004; Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2006, Reference Baron-Szabo2008; and present study).

Americas: Greenland, Jamaica, Mexico, Peru, USA

Studies on the K/Pg sections in the Nûgssuaq area of Greenland are few (Floris, Reference Floris1972). As far as Maastrichtian coral occurrences are concerned, only two solitary taxa from coastal environments have previously been recorded.

The rich coral fauna of Jamaica, occurring mainly in coral-rudist associations, has long attracted the attention of palaeontologists who focused on Late Cretaceous and K/Pg boundary assemblages. Collecting efforts by Coates, Kauffman and Jackson between 1966 and 1972 (collections of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC) have provided insights into the most extensive Maastrichtian coral fauna known (Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2002, Reference Baron-Szabo2006, Reference Baron-Szabo2008). The corals inhabited a mixed volcaniclastic-carbonate platform (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2002; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Stemann, Blissett, Brown, Ebanks, Gunter, Miller, D., Pearson, Wilson and Young2004) at shallow subtidal depths. They are distinctly dominated by zooxanthellate forms (Tables 4 and 5).

Maastrichtian corals from Mexico have been described from both northern (Myers, Reference Myers1968; Schafhauser et al., Reference Schafhauser, Götz, Baron-Szabo and Stinnesbeck2003; Baron-Szabo et al., Reference Baron-Szabo, Schafhauser, Götz and Stinnesbeck2006) and southern areas (Filkorn et al., Reference Filkorn, Avendano-Gil, Coutiño-José and Vega-Vera2005; Löser, Reference Löser2012), from both reefal environments (Schafhauser et al., Reference Schafhauser, Götz, Baron-Szabo and Stinnesbeck2003) and non-reefal mixed clastic/carbonate sequences (Baron-Szabo et al., Reference Baron-Szabo, Schafhauser, Götz and Stinnesbeck2006). The Mexican assemblages consist nearly exclusively of colonial forms and are characterised by a moderate to high species richness.

Very little is known about the coral facies of Peru. Wells (Reference Wells1941) noted one colonial coral species from lithologically unspecified sedimentary rocks. In contrast, coral occurrences have been reported from numerous localities across the USA (Table 3). However, these are rather monospecific, consisting almost exclusively of solitary forms such as Micrabacia and Trochocyathus (Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1916; Vaughan, Reference Vaughan1920; Wells, Reference Wells1933; Gill et al., Reference Gill, Cobban and Kier1966; Sohl & Koch, Reference Sohl and Koch1984; Bryan & Jones, Reference Bryan and Jones1989) (Tables 4, 5). The sole colonial forms known from the Maastrichtian of North America belong to Astrangia and Hindeastraea (Table 4).

Antarctica: James Ross Basin (Seymour Island, Snow Hill Island)

A rather small coral occurrence has been described from James Ross Basin (Filkorn, Reference Filkorn1994; Videira-Santos et al., Reference Videira-Santos, Tobin and Scheffer2022), comprising nearly exclusively solitary forms with medium- to large-sized corallites. The sole colonial species is the subplocoid-subbranching Pleurocora haueri. These corals have been recovered from both the inner shelf and estuarian or bay environments (Tables 3–5).

Asia: India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Oman, Russia, Türkiye, Turkmenistan and United Arab Emirates

Maastrichtian corals from India are known from old reports based on stratigraphical data that are difficult to reassign to or fit in with modern chronostratigraphy. In the present study, only the material described by Forbes (Reference Forbes1846) and Stoliczka (Reference Stoliczka1873) is included and compared to data presented by Sundaram et al. (Reference Sundaram, Henderson, Ayyasami and Stilwell2001). No bioconstructions have been reported from this area. Corals described are solitary forms, belonging exclusively to the large-polyp group (Tables 4, 5).

Maastrichtian corals from Iran were first assessed taxonomically on the basis of material from the coral-rudist limestone of the Neyriz area by Kühn (Reference Kühn1933). Recently, new material from various localities across Iran has been recorded (Khazaei et al., Reference Khazaei, Yazdi and Löser2009; Baron-Szabo et al., Reference Baron-Szabo, Schlagintweit and Rashidi2023), thus significantly increasing the number of coral species to the level of moderate to high species richness. The corals originate from sedimentary rocks assigned to the upper Maastrichtian Tarbur Formation, interpreted to have formed under shallow subtidal conditions.

A small number of predominantly solitary corals were described from various countries of the former Soviet Union (Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan) by Kuzmicheva (Reference Kuzmicheva1985, Reference Kuzmicheva1987). The sole (branching-) colonial species (Ogilviastraea bigemmis) was reported from Kazakhstan. Solitary forms comprise caryophylliids, parasmiliids and smilotrochids. All of the corals have large-sized corallites. In most cases, information on the lithology of the coral-bearing sedimentary rocks was not supplied (Tables 3–5).

Coral-bearing sedimentary rocks of the latest Cretaceous age in the Arabian Peninsula were described from several sections in Oman and the United Arab Emirates (Metwally, Reference Metwally1996; Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2000). Stratigraphically, most of these strata are assigned to the time period upper Campanian–lower Maastrichtian interval. Only nine taxa, nearly all of which are colonial, were collected from rocks dated as Maastrichtian. The single solitary form from this region belongs to Cunnolites, while colonial taxa comprise cerioid-plocoid and (hydno-) thamnasterioid-meandroid species (Tables 4, 5).

Very little is known about the Maastrichtian coral facies of Türkiye. From the southeastern part of the country, at Gevaş-Van, Özer (Reference Özer1992) figured material that is here assigned to the colonial form Aspidastraea orientalis. Recently, Görmüş et al. (Reference Görmüş, Demircan, Kadioğlu, Yağmurlu and Us2019) have mentioned an abundant occurrence of Cunnolites sp. from the Ankara area in the northwest. Reefal developments were reported from the Gevaş-Van locality in southeastern Türkiye, and shallow-subtidal conditions were described from the western part of the country (Tables 3–5).

Australasia: Australia

In a recent review of Cretaceous corals, Jell et al. (Reference Jell, Cook and Jell2011) described the first scleractinian coral fauna from deep subtidal sedimentary rocks in Western Australia, the assemblage consisting of 12 taxa is distinctly dominated by solitary species having conical growth forms. The sole colonial taxon is the cerio-plocoid Astrangia. The solitary species belong to a fairly large number of families: Caryophylliidae, Dendrophylliidae, Flabellidae, Fungiacyathidae, Parasmiliidae, Smilotrochidae and Turbinoliidae (Tables 1, 3–5).

Europe: Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands-Belgium, Poland, eastern Serbia, Spain and Ukraine

The diversity of Maastrichtian coral occurrences across Europe varies significantly. With the exception of the coral assemblage described from the southern Netherlands and northeast Belgium (Leloux, Reference Leloux1999, Reference Leloux2004; Figs. 2–9 herein), European coral faunas consist of nine species or less (Table 5). The Dutch-Belgian coral fauna from the Liège-Limburg area (i.e. the type area of the Maastrichtian Stage) represents the second most diverse coral occurrence known from the Maastrichtian. It is composed mainly of colonial taxa, having all types of corallite integration (Tables 4, 5). Reefal developments were reported from coral-bearing sedimentary rocks of Bulgaria and Spain.

General attributes of scleractinian corals from the Maastrichtian

A total of 205 taxa, belonging to 116 genera and 37 families, are recognised from 94 localities in 26 regions with Maastrichtian strata world-wide (i.e. 170 species identified, 35 taxa kept in open nomenclature). Most of the taxa belong to solitary (41 genera = 35%; 83 species = 40.5%) and cerioid-plocoid forms (41 genera =%; 64 species = 31.2%) followed by corals having various kinds of (hydno-) thamnasterioid-meandroid integration (25 genera = 22%; 42 species = 20.5%) and branching types (9 genera = 8%; 16 species = 7.8%) (Tables 2, 4).

With regard to corallite size, 186 taxa are included in the present evaluation (19 species were omitted due to a lack of sufficient data) (Table 4). In Maastrichtian corals, corallite diameters range from less than 1 mm (e.g. Actinacis martiniana, Heterocoenia gracilis [see Fig. 9B], Stylophora garumnica) up to around 100 mm (e.g. species of Cunnolites such as C. rugosus) (Table 4) and fall into three major corallite-size groups: small (up to 2.5 mm), medium (>2.5–9 mm) and large (>9 mm). However, Maastrichtian scleractinians are nearly equally dominated by forms with medium-size (80 species = 43%) and large-size corallites (71 species = 38.2%), followed by small-corallite forms (35 species = 18.8%).

Based on the model of evolution of scleractinian corals using microstructural data (Roniewicz & Morycowa, Reference Roniewicz and Morycowa1993), Maastrichtian coral faunas show a distinct predominance of taxa belonging to modern microstructural groups (86 genera = 74%; 145 species = 70.7%) (Tables 1, 4). In comparison with the situation of both the lowermost Cretaceous (Berriasian), which showed that 91% of species and 83% of genera belonged to previously established microstructural groups (Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2018), and to the uppermost Lower Cretaceous (Albian), which ended with modern microstructural groups having become dominant (genera = 51.7%; species = 50.1%; see Baron-Szabo, Reference Baron-Szabo2021a, Reference Baron-Szabo2021b), previously established microstructural groups were of minor importance during the latest Cretaceous.

The most extensive records of Maastrichtian corals are from warm-temperate (53 out of 94 localities = 56.4%) and arid areas (20 out of 94 localities = 21.3%), including the USA, Australia and various European and Asian countries (Table 3). The most diverse coral assemblages have been reported from arid (Jamaica, Mexico), warm-temperate (the Netherlands-Belgium) and tropical regions (Iran) (Tables 3–5). As far as genus-level distribution is concerned, 34 genera (out of 116 genera = 29.3%) have been recorded from two or more localities (Table 4). The most widely distributed of these genera during the Maastrichtian belong to various solitary and colonial taxa, including Actinacis, Actinastrea, Actinhelia, Aspidastraea, Caryophyllia, Cunnolites, Dendrophyllia, Desmophyllum, Goniopora, Neocoenia, Palaeopsammia, Paracycloseris, Parasmilia, Smilotrochus, Stylophora, Synastrea and Trochocyathus (Figs. 2–9; Table 4). With regard to species distribution, a clear majority of taxa (155 taxa = 75.6%) has been recorded from only one geographic region during the Maastrichtian (Table 4).

In general, Maastrichtian coral diversity is very low with many occurrences consisting of 10 or fewer taxa (Table 5). The four most diverse coral assemblages recorded for this time slice are those from Jamaica (51 genera, 63 species), the Netherlands-Belgium (28 genera, 32 species), Mexico (24 genera, 29 species) and Iran (20 genera, 27 species) (Tables 4, 5). Comparing the species of the most diverse faunas, the coral assemblages from Jamaica and Mexico show the greatest correspondence (17.4%), followed by Mexico and the Netherlands-Belgium (4.9%) and Jamaica and Iran (3.3%).

Discussion and conclusions

Material derived from coral-bearing Maastrichtian sedimentary rocks from 94 localities in 26 regions world-wide has been considered in the present study (Fig. 1, Table 3). A total of 205 taxa in 116 genera, belonging to 37 families, are recorded (170 taxa assigned to species, 35 taxa are kept in open nomenclature) (Tables 1, 4, 5). In general, the corals inhabited various non-reefal settings, including coastal, deltaic, lagoonal and shallow to deep subtidal palaeoenvironments. Only from Bulgaria, Mexico, Oman, Spain and western Türkiye have corals been recorded from various types of reefal bioconstructions (Table 5). The most extensive records of Maastrichtian corals are from warm-temperate settings (53 out of 94 localities = 56.4%) followed by arid areas (20 out of 94 localities = 21.3%), including the USA, Australia and various European and Asian countries (Table 3).

Corals occurring in reefal developments have been recorded mainly from para- to subtropical (Bulgaria, Spain, western Türkiye) palaeoenvironments, followed by arid (Mexico) and tropical (Oman) areas. The most diverse corals faunas, however, are those from non-reefal sedimentary rocks of arid (Jamaica) and warm-temperate (the Netherlands-Belgium) regions (Tables 3, 5).

The most dominant group of coral taxa comprises forms that have no or very low corallite integration (48.3%: 83 solitary species = 40.5%; 16 branching forms = 7.8%), followed by those with cerioid-plocoid (64 species = 31.2%) and various kinds of (hydno-) thamnasterioid-meandroid integration (42 species = 20.5%) (Table 3).

As far as corallite size is concerned, 186 taxa have been included in the present evaluation (19 species were omitted due to a lack of sufficient information). In Maastrichtian coral assemblages, species with medium- and large-sized corallites predominate: 80 species (43%) belong to the medium-sized group, 71 species (38.2%) have large-sized corallites, and 35 species (18.8%) show smallcorallite diameters (Table 3). Nearly a third of the Maastrichtian corals are large-polyp solitary forms (55 species = 29.6%), while most of the cerioid-plocoid species have either medium- (31 taxa = 16.7%) or small-sized (26 taxa = 14%) corallites (Table 2). As a trend, it may be stated that the degree of corallite integration correlates to the size of the corallites. The least integrated forms have the largest corallite diameters: 59 species (out of 71 species) of the large-sized corallite group (83%) belong to solitary or branching types; 31 species (out of 35 species = 88.6%) of the small-sized corallite group have medium- (cerioid-plocoid) to highly integrated ([hydno-] thamnasterioid-meandroid) corallites.

A clear majority of the species (152 taxa = 74.2%) has been recorded from a single region only. The taxa were thoroughly revised applying the exact same taxonomic model to all forms. Possible reasons for this feature of apparent endemism might include, for instance, ecological/environmental issues and/or the fact that sampling efforts were not the same at each site. In some areas (the Netherlands-Belgium, Jamaica, etc.), Maastrichtian coral research has a long history (over two centuries), whereas in other regions (e.g. Türkiye, India, Peru and Russia), coral research has been limited in scope and extent to nearly non-existent.

Only 23 species (11.2%) that have been found in more than one locality are cosmopolitan to subcosmopolitan during the Maastrichtian, most of which are solitary (16 species): Bathycyathus lloydi, Caryophyllia konincki [(see Fig. 3A, B), Cunnolites cancellata (see Fig. 4F, G), Cunnolites giganteus, Cunnolites polymorphus (see Fig. 2E, F), Deltocyathus cupuliformis, Desmophyllum excavatum, ?Flabellosmilia vaughani, Micrabacia radiata, Palaeopsammia zitteli, Paracycloseris nariensis, Parasmilia elongata, Smilotrochus milneri, Smilotrochus ponderosus, Trochocyathus mitratus and Trochocyathus speciosus. Seven cosmopolitan to subcosmopolitan species belong to colonial forms: Actinhelia elegans (see Fig. 2D), Columactinastraea fallax (see Fig. 4E), Fungiastraea flexuosa (see Fig. 8G, H), Goniopora imperatoris, Neocoenia (Placocaeniopsis) rotula (see Fig. 6B), Ogilviastraea bigemmis and Stylophora octophylla (Table 4).

With regard to both genus and species levels, a significant majority of the taxa (82 genera out 116 = 70.7%; 155 taxa out of 205 = 75.6%) appears to be endemic during the Maastrichtian, having been reported from a single locality only (Table 4). The four most diverse coral assemblages recorded for the Maastrichtian are those from Jamaica (63 species), the Netherlands-Belgium (32 species), Mexico (29 species) and Iran (27 species). A comparison of the species of the most diverse faunas reveals that the assemblages from Jamaica and Mexico show the greatest correspondence (17.4%).

Coral faunas of the Maastrichtian show a distinct predominance of those taxa that represent modern microstructural groups (86 genera = 74%; 145 species = 70.7%) (Tables 1, 4).

Acknowledgements

Our thanks and gratitude go to Dennis Opresko (Knoxville, TN) for his valuable suggestions on an earlier version of the typescript and together with both Steve Cairns (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA) and Bernard Lathuilière (Nancy, France), for many discussions on coral taxonomy.

Type specimens and additional study material were made accessible to us by Natasja den Ouden (Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, the Netherlands); Andreas Kroh, Alexander Lukeneder, Oleg Mandic and Thomas Nichterl (all Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria); Hans Egger (Geologische Bundesanstalt, Wien; GBA, Vienna, Austria); Sylvain Charbonnier and Christine Perrin (both Muséum national d‘Histoire naturelle, Paris, France); Winfried Werner and Martin Nose (both Bayerische Staatssammlung, Munich, Germany); Jill Darrell (the Natural History Museum, London, UK); Dieter Korn (Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany) and John W.M. Jagt (Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht). As a Research Associate of the Smithsonian Institution (SI), Washington, DC (USA), and an Honorary Researcher at the Research Institute Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main (Germany), the senior author wishes to express her deep appreciation for the continuing support from these institutions. The junior author is honoured to have been asked to co-operate in and contribute to this paper. Finally, we appreciate comments made by Bodil Lauridsen, by guest editor John W.M. Jagt and by an anonymous reviewer.