Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 was a shocking reminder that the question of nationalism in the post-Soviet space remains a source of conflict and instability. It was the very success of Ukraine’s nation-building efforts, and their desire to join the European community of nations, that drove Putin to launch the invasion. Putin’s vision of Russian identity could not tolerate the existence of an independent Ukraine embedded in Western institutions. The implications of Putin’s actions for other newly-independent states with large Russian minorities, such as Estonia, Latvia, Moldova, and Kazakhstan, are alarming.

The collapse of the three socialist federations (Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union) into independent states in 1991–92 triggered a flurry of nation-building by newly-empowered elites (Bremmer and Taras Reference Bremmer and Taras1997). All 15 sovereign nation-states that came out of the Soviet Union have survived 30 years of independence, so the nation-building can broadly be considered a success. However, four countries lost control over secessionist provinces (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine).

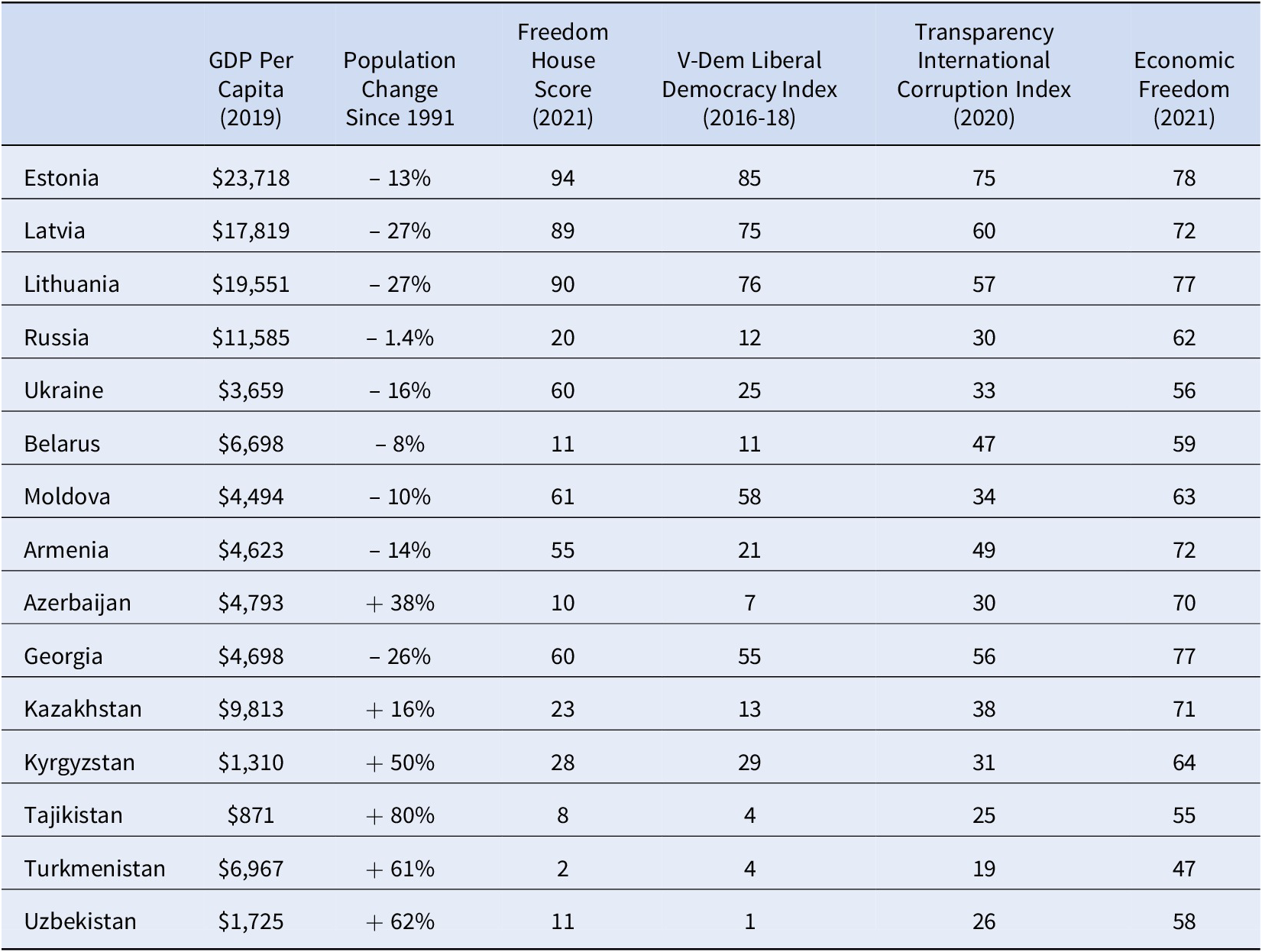

The post-Soviet states have experienced widely varying degrees of economic prosperity and political freedom.

Initially there was optimism that the shift to independence would be accompanied by democratization (Nodia Reference Nodia1992), but most countries fell off the democratic path into authoritarianism, or in some cases (such as Kyrgyzstan) near-anarchy (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2000; Hale Reference Hale2008). The Baltic states are the outliers: they joined the European Union and NATO in 2004, and have drawn equal to or ahead of countries like Poland and Greece in GDP per capita and democracy rankings (Pettai Reference Pettai2019). The population dynamics also vary widely: demographic decline in the western states contrasts with surging populations in Central Asia.

In each country the task of nation-building took place alongside state-building and market-building (Smith et al. Reference Smith1998; Smith Reference Smith1999). For all its defects, the Soviet Union was a developed, well-functioning state, which meant that the post-Soviet states started out with strong coercive institutions, delineated borders, and robust educational systems, postal services, transportation infrastructure, etc. (Driscoll Reference Driscoll2015). In this respect, they were in much better shape than were the post-colonial states in Africa (Beissinger and Young Reference Beissinger and Young2002). However, there were some large gaps in the state capacity: the newly-independent states had to create a host of market institutions from scratch – central banks, national currencies, commercial codes, stock markets, etc. On top of that, the turmoil caused by the break-up of the Soviet Union (with most economies experiencing a 40% drop in GDP in the early 1990s) meant that some of the existing state institutions virtually collapsed – including parts of the health, education, and social welfare systems.

The first wave of nationalist politics in the late 1980s was closely connected to the spread of democracy, under the policies of glasnost and perestroika. It was widely assumed in the West that these countries would rapidly transition to liberal democracies and market economies: Francis Fukuyama famously proclaimed “the end of history” in Reference Fukuyama1989. However, competitive elections often provided an impetus to nationalist mobilization. The path from voting to violence was often perilously short (Snyder Reference Snyder2000). In Central Europe, the appeal of a “return to Europe” meant that nationalism and democracy worked in tandem: Poland’s national interests would be served by embracing democracy, since that would enable them to join NATO and the European Union. This was also true in the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – whose bid for independence in 1988–91 was instrumental in bringing about the collapse of the Soviet Union. Elsewhere, however, in Belarus, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, the newly-independent states fell under the control of authoritarian rulers, and nationalism became associated with the repression of political opposition in the name of building a stronger state.

Western liberals’ faith in the synergy of nationalism and democracy was revived by the “color revolutions” of 2003–05 in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine, where rigged elections triggered mass protests and the toppling of autocratic leaders. This process was repeated in Ukraine’s Maidan revolution of 2014 and Armenia’s “Velvet Revolution” of 2018. However, the democratic promise of the color revolutions has been overshadowed by the embrace of reactionary, anti-liberal ideologies by authoritarian leaders – not just Vladimir Putin, but also democratically elected leaders in Poland and Hungary, where post-socialist nationalists are making common cause with West European anti-immigrant populists.

The Components of Nation-Building

The new states emerged out of decades of Soviet rule, and the Soviet legacy weighed heavily on their nation-building efforts. In some respects, the Soviet experience provided a solid foundation for nation-building, and in others a barrier that had to be overcome. While trying to transcend nationalism through the creation of a “new Soviet man,” the Communist state also institutionalized ethnicity since it was a federation of ethnically-titled units, within which national languages and cultures were developed, and intellectual and political elites emerged (Martin Reference Martin2001). All Soviet citizens were identified as members of a particular nationality in paragraph five of their passport. Resistance to Soviet rule was met with harsh repression, often targeting entire ethnic groups. The secessionist provinces that split from five of the 15 states after 1991 (including Russia, which fought to prevent Chechen independence) all originated as sub-units of Soviet federalism.

Since independence, elites in each state have energetically pursued the process known as “nation-building.” Nation-building has various components, and states tackled the process with varying degrees of success. They all managed to establish and maintain their sovereignty, contrary to the expectations of many skeptics who doubted that states such as Moldova or Kyrgyzstan, seen as artifacts of Soviet nationality policy, would survive the independence that was thrust upon them in 1991. After independence, what Rogers Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2011) called the “nationalizing state” got to work filling the inherited, Soviet-drawn republican territories with new national content, like water filling up a container. Despite the rise of economic globalization and the internet communications revolution, nationalism had not lost its capacity to serve as a focal point for elite unity and to stir public emotions – especially in the face of political instability and economic deprivation. As Ronald Suny observed, “national identities … are saturated with emotions… . The dread of personal oblivion, the need for redemption, salvation, and eternity are all answered in the nation” (Reference Suny2001, 894).

Gender has also been central to the nation-building process. Soviet-style gender equality, limited as it was, was abandoned in favor of the promotion of “traditional” gender roles for women, meaning a focus on the home and motherhood. While Azerbaijan and Central Asia continued to experience rapid population growth, Russia and the other states adopted pro-natalist policies in a bid to slow demographic decline.

The classic models of nation-building in Europe or Latin America from the 19th century posited some tried-and-tested policy levers for creating a unified, homogenous national community (Gellner Reference Gellner1997; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1992; Anderson Reference Anderson1991). They include:

-

– Imposition of a single national language through the school system and media;

-

– Cultivation of national pride through the promotion of a common national history and repertoire of heroes, monuments, and rituals;

-

– Military conscription and the commemoration of victories (and defeats) in past and current wars;

-

– Creation of an integrated national market, led by a strong national bourgeoisie, with a robust infrastructure and welfare state; and

-

– Sport and other mega-events (such as the Eurovision song contest) to serve as a vehicle for mass involvement in displays of national pride.

There are some important choices to be made by nation-builders. What are the criteria for inclusion in the nation: ancestry, language, religion? Does the narrative of national identity recognize the role of ethnic and linguistic minorities – or is the nation treated as the sole property of a single ethnic group? Are special rights granted to ethnic minorities – to education and media access in their native language, for example? Most of the states embraced an inclusive, civic approach, awarding citizenship to all residents as of 1991 irrespective of ethnicity (except for Estonia and Latvia, which restricted citizenship to the descendants of pre-1940 citizens) (Shevel Reference Shevel2009; Barrington Reference Barrington2021). They all dropped the Soviet practice of recording inherited ethnicity in citizens’ identity documents. Russia, Armenia, Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan allow dual citizenship, the remaining states do not (while allowing some exceptions). For example, Latvia has allowed dual citizenship for EU nationals since 2013 (Zevelev Reference Zevelev2021).

Even while adopting a relatively inclusive approach to citizenship – not excluding ethnic minorities from citizenship – all these states made a priority of using and teaching the language of the titular nationality (that is, the nation after which the state is named) as the official state language. They varied in the speed and intensity with which this policy was pursued, and the degree to which there was some official recognition of minority languages (allowing some teaching in minority languages in the school system, for example). Using Şener Aktürk’s taxonomy (Reference Aktürk2021), only Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania adopted a mono-ethnic approach, strongly institutionalizing the prerogatives of the titular group. The others (such as Russia and Moldova) went for a weakly multi-ethnic approach, reflecting the legacy of the Soviet period. The fact that inclusive citizenship policies can be combined with relatively exclusive national narratives, highlighting the role of the leading titular ethnic group, adds another layer of complexity to the traditional divide between “civic” and “ethnic” nation-building strategies – exemplified by the historical experiences of France versus Germany (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1992).

National narratives are always nested in broader trans-national identities. Nations must position themselves on the international stage – for example, as part of Europe or Eurasia, or as a member of a broader cultural or linguistic community (Turkic, Russian-speaking, etc.) (Graney Reference Graney2019). These geopolitical choices may exacerbate domestic ethno-political divisions – most graphically in the case of Ukraine, torn between pro-Western and pro-Russian sentiments. A judicious balancing of geopolitical narratives has preserved inter-ethnic peace in Kazakhstan (albeit in the absence of democracy). There was concern that Russia would exploit the situation of the 25 million ethnic Russians living outside the Russian Federation to pressure the newly-independent states (Commercio Reference Commercio2011), and indeed this is one of the excuses Putin used to annex Crimea in 2014 and attack Ukraine in 2022.

A widespread feature of all nationalist movements is the identification of a group that is seen as a threat to the existence of the nation – the “Other” – against which boundaries must be drawn and defended. In Georgia and Azerbaijan, it was internal ethnic minorities whose demands for self-rule posed a threat to the state’s territorial integrity. For Armenia, Azerbaijan was the Other – ruling over Armenians in Karabakh, but also associated with the Ottoman Turks who had committed the 1915 genocide. For nation-builders in the Baltic states, and for most nationalists in Ukraine and Moldova, Russia represents the threatening Other. For the rulers of Belarus and Russia, the West is the Other. Nationalists link external and internal enemies – portraying domestic opponents as a “fifth column” supporting the external foe. In Central Asia, the evils of the Soviet past represented the Other, such as the collectivization campaign that killed over one quarter of the population of Kazakhstan. The new threat of Islamist terrorism, spilling over from Afghanistan, was also central to states’ legitimation strategies, particularly in Uzbekistan.

The countries that faced secessionist uprisings blamed Russian interference, which was a key factor in explaining the persistence of the conflicts in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Karabakh, and Transnistria (Rutland and Kazantsev Reference Rutland and Kazantsev2020). Russia regained formal sovereignty over the break-away region of Chechnya in 2002, though the relationship with Chechen president Ramzan Kadyrov remains tense.

Aside from these secessionist cases, the demarcation of mutual borders went relatively smoothly. As in the case of postcolonial Africa, pre-existing administrative boundaries became international borders overnight under the principle of uti possidetis (“as you possess”). One of the more problematic regions is the Fergana Valley, where pockets of Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Kyrgyz live in exclaves located in the territory of another state (Megoran Reference Megoran2017). Dozens were killed in armed clashes on the Tajik-Kyrgyz border in April 2021 and September 2022. Russia and Estonia have yet to confirm their common border: a treaty was signed in 2014 but has not been ratified by either side.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and support for secessionists in the Donbas represented a radical break with the general pattern of settled borders, alarming the leaders of other states, such as Kazakhstan. The full-scale invasion that Putin launched in February 2022 represented an even more radical effort to roll back the dissolution of the Soviet Union, at least with respect to Ukraine.

In explaining nationalism in the post-Soviet space, instrumentalist leaders loom large – that is, politicians who use nationalist appeals to help consolidate their hold on power (Snyder Reference Snyder2000). Elite manipulation arguably played a bigger role than other factors often used to explain the rise of nationalism such as cultural legacies (“ancient hatreds”), the scheming of nationalist intellectuals, or the abstract logic of modernization. Most of the countries saw the birth of a nationalist movement in civil society in the late Soviet period, in intellectual groups or grass-roots movements, but after 1991 it usually was captured by the new ruling elite, who used it to consolidate their own power, marginalizing rival elites who had alternative nation-building projects through cooptation and/or repression. This is a pattern familiar from nation-building in postcolonial African states in the 1960s: national unity supposedly requires political unity, which requires loyalty to the incumbent ruler (Beissinger and Young Reference Beissinger and Young2002). Consequently, what we are seeing is not so much nation-building as it is identity management and regime maintenance behind a façade of nation-building. Nationalist politics in the post-Soviet space fit into the pattern of elite “political technologies” analyzed by Wilson (Reference Wilson2005), Hale (Reference Hale2015), and Way (Reference Way2015), where the main driver is incumbent elites maneuvering to stay in power. These leaders are primarily concerned with consolidating their rule: implementing policies to reinvent national identity is a lower priority for them.

While authoritarian rulers pressed ahead with their nation-building programs, states that tried to follow a democratic path found that political competition resulted in polities too polarized for effective nation-building. Ukraine was divided between pro-Western and pro-Russian regions, who disagreed over the pace of promotion of Ukrainian language and integration with the West. Over the years, political power in Kyiv passed back and forth between the two groups, until the Crimea annexation led to a new sense of unity amongst Ukrainians. Russia itself also illustrates this phenomenon. In the 1990s it still had a competitive political system: there was a free press, and a degree of uncertainty over who would win the 1996 presidential and 1999 State Duma elections. After Putin’s accession to the presidency in 2000, however, democracy was shut down. The state reasserted control over television, and presidential and parliamentary elections ceased to be competitive. Freedom House downgraded Russia to “unfree” in 2004. At the same time, Putin was able to rebuild Russia’s national pride and sense of purpose. So if at the start of the 1990s in Russia democracy and nationalism were working together, the one reinforcing the other, by the 2000s they were pulling in opposite directions.

From Nation-Building to Ethnicity Management

The main trend in the contemporary literature on nationalism in Europe and elsewhere is to stress hybridity and fluidity, moving beyond the assumption that a nation-state should be homogeneous and mono-ethnic (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, Reference Brubaker2002, Reference Brubaker2011; Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2016). To some degree, the post-Soviet nations were still influenced by the fixed categories inherited from Soviet ethnicity theory and policy (such as the assumption that each person, and each territory, has one nominal ethnic identity). But the reality is that the post-Soviet states are predominantly multi-ethnic and multi-lingual societies.

Geographic mobility has increased since 1991, both within states and across international borders. Russia is host to a large migrant worker community, amounting to some 10% of the total population. Over one quarter of the population of the smaller, poorer countries such as Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Kyrgyzstan have left to work in Russia or elsewhere, and their remittances make up a large share of their home countries’ economy (Mansoor and Quillin Reference Mansoor and Quillin2006). This complicates the nation-building process in both the sender and receiver countries. To some extent national identities are being “deterritorialized”: membership in the national community no longer necessarily coincides with residence in and citizenship of the nation-state. Elites have learned to live with this complexity and hybridity and turn it to their advantage: the rich acquire foreign passports and hide their wealth overseas.

But this situation poses new challenges for nationalists: how to preserve the national community in the face of declining population due to out-migration and declining birth rates? This is a major challenge for the Baltic states: despite their success in building stable democracies and successful economies, entry to the EU made it possible for young people to seek better opportunities elsewhere. The population of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania has contracted by 13%, 27%, and 27% respectively since independence (Rutland Reference Rutland2021). Even before the Ukraine war, Russia itself had seen more than 3 million of its citizens move abroad, many of them highly educated.

In authoritarian regimes, “thick” or deep national identity may not be necessary or desirable: over-enthusiastic nation-building may antagonize ethnic minorities or empower radical nationalist actors who could challenge the authority of the leader. At some conjunctures, and on certain issues, leaders may find it useful to mobilize people around a nationalist agenda: but at other times they may want to demobilize them. This is an example of what Hutchinson (Reference Hutchinson2005) has called “episodic nationalism.” In the face of ethnic pluralism, inclusive civic identities may be more useful for state-building authoritarian rulers than exclusive ethnic identities. These authoritarian regimes are usually trying to constrain or dismantle independent civil society organizations – including nationalist groups of both the majority and minority communities (as in Azerbaijan or Kazakhstan, for example).

Arguably, what we are now seeing in much of the region is not so much nation-building as identity management of a multi-ethnic citizenry – a process similar to what is happening in Britain, France, and many countries around the world. The post-Soviet states face a range of options in dealing with ethnic minorities within their borders – assimilate, tolerate, ignore, or expel (Mylonas Reference Mylonas2012). The “nationalizing states” that pursued assimilation sometimes found that aggressive efforts to promote a monolithic identity could backfire, triggering secessionist rebellions in Georgia and Moldova – aided and abetted by Russia, and actually initiated by Moscow in the case of Crimea and the Donbas. Second, these states have come under pressure from the international community to respect minority group rights. Estonia and Latvia were able to withstand this pressure and moved forward with a rigorous nation-building program, leaving one quarter of their initial population stateless, and insisting on exclusive use of the titular language in most schools and in public institutions. Even there, ethnic Russians who have learned Estonian or Latvian and acquired citizenship are not necessarily losing their Russian identity.

“Managing” ethnic identities differs from “nation-building” in that it recognizes a plurality of ethnic groups with certain rights to use their own language and preserve their own customs and does not promote a linear trend towards homogeneity (Smith Reference Smith2013). Ethnicity management shares with nation-building the assumption that the state is the dominant actor in the process, manipulating group identities in order to achieve the goals of the central executive (Marko Reference Marko2007). The terms “ethnicity management” or “diversity management” are widely used in Western personnel management, in the context of promoting a diverse workforce. The terms are not commonly deployed by political scientists, though they have been used in Europe with reference to minority group rights (Malloy Reference Malloy2007) – for example, in post-war Kosovo (Landau Reference Landau2017).

As Rasma Karklins (Reference Karklins2021) points out, in Latvia certain spheres of activity are being “de-ethnicized” (such as business) while others are “essentialized” for political reasons (such as the teaching of history). Ukraine exemplifies the complex and contradictory character of state-building in a multi-ethnic society. As the 2014 Maidan revolution unfolded, most of the cities in eastern Ukraine with a majority of Russian-speakers (including many ethnic Russians) sided with the new pro-Western government in Kyiv. Why pro-Russian separatists were able to seize power in Donetsk and Luhansk but not in Kharkiv, Odessa, or Mariupol seems to have been driven by regional identities and oligarch politics, and not by ethno-nationalist or geopolitical agendas (Matsuzato Reference Matsuzato2018).

Nowhere is the tension between nation-building and ethnicity management more acute than in the Russian Federation itself, born out of a communist state and former empire that were both multi-ethnic projects and not nation-states (Kolstø and Blakkisrud Reference Kolstø and Blakkisrud2004, Reference Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016). With non-ethnic Russians amounting to 20% of Russia’s citizens, Putin’s policy has oscillated between nation-building around the Russian core on one hand and expressions of respect for the multi-ethnic character of Russian civilization on the other. Putin’s willingness to grant free rein to Ramzan Kadyrov’s nation-building in Chechnya is the most extreme example of this pluralistic approach (Souleimanov and Jasutis Reference Souleimanov and Jasutis2016); the 2017 decision to limit teaching in the native language in the schools of Tatarstan and elsewhere is an example of the contrary trend (Yusupova Reference Yusupova2018; Prina Reference Prina2016). Putin has pursued strategic ambiguity in his ethnicity policy: sometimes ethnic, sometimes civic, always imperial. He has toyed with an expansionist agenda of protecting the rights of Russians and Russian-speakers in neighboring countries, promoting the idea of a “Russkii mir” (Russian world). However, after the annexation of Crimea, Putin did not follow the more ambitious territorial expansion program (“Novorossiia”) promoted by Aleksandr Dugin and others. Much to the chagrin of Russian nationalists, Putin did not recognize the independence referenda in Donetsk and Luhansk in 2014, preferring to see those provinces remain part of Ukraine, but with a high degree of autonomy, effectively beyond the control of the Kyiv government. That compromise position was overturned by the invasion of February 2022, which was followed by the formal incorporation of the occupied territories of Ukraine into Russia on September 30, 2022.

The Impact of Globalization

Economics tends to be left out of most debates about national identity. The post-Soviet transition coincided with a sharp increase in the level of global economic integration (Akimov and Kazakevitch Reference Akimov and Kazakevitch2020). Liberalization of trans-national capital flows meant increased exposure to cyclical financial crises, causing currency devaluations and bank collapses. Given the prevailing neoliberal paradigm, it was hard for countries to implement economic nationalism policies, such as subsidies for industrial and agricultural producers, or local content rules for investors. The tide of globalization peaked with the 2008 financial crisis, but it remains a potent force.

Globalization is not causing nations and nationalism to disappear, but it is disrupting their political systems (Manet Reference Manet2006; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2013) and bringing new idioms of nationhood (Aronczyk Reference Aronczyk2013). Nation-building is not only about creating a community of citizens who identify with the nation: it also requires creating a set of institutions which meet the needs of international investors and global regulatory institutions. Nation-builders of the 21st century face a very different economic environment than those of the 1960s or 1860s. Economic success hinges on integration into the global economy, which means a high level of trade and openness to foreign investment. Nation-building is less about creating a homogenous nation, and more about locating your nation in the international cultural, economic, and military space – from alliance membership to nation-branding (Graney Reference Graney2019). It turns out that authoritarian, patronal political regimes with crony capitalist economies are perfectly compatible with global integration: globalization does not push countries to become democracies.

Most of the post-Soviet states have found it hard to find their niche in the international division of labor, due to their geographic isolation, weak rule of law, and corrupt political regimes (Havrylyshyn Reference Havrylyshyn2020). Many countries have found that their role in the global economy is as a source of labor, with an exodus of both skilled and unskilled workers from Central Asia, the south Caucasus, Belarus, and Ukraine to Russia; and from Ukraine, Moldova and the Baltics to the EU. Some 25% of the GDP of Tajikistan and Moldova consists of remittances from migrant workers – one of the highest rates in the world, second only to Central America (Mansoor and Quillin Reference Mansoor and Quillin2006).

The Baltic countries aside, when it comes to economic prospects the remaining post-Soviet states fall into two camps: the energy rich (Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan) and the energy poor (the rest). Belarus and Ukraine were able to share in some of the energy rents thanks to their role as transit countries for the export of Russian oil and gas to Europe, though this broke down for Ukraine after 2014, by which time Russia had built alternate export pipelines. The Central Asians are building more pipelines to China to decrease their dependence on Russia as a destination for their oil and gas.

The Baltic states benefited from their proximity and hence rapid entry to the EU, but for the other states, the prospects for entry to the EU were slim. Although in 1990 the Baltic Popular Fronts had talked about following the example of Finland and adopting neutrality, after independence the Baltics followed Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic in pursuing NATO membership (Piirimäe Reference Piirimäe2020, 12). NATO was willing to expand eastwards because of the unstable politics of Russia, exemplified by the shelling of parliament in October 1993 and Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s first-place finish in the December 1993 Duma elections, which meant that there was still a chance of a return to power in Moscow of hardliners willing to use force to establish Russian control over the post-Soviet space. Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova were torn between a desire to pursue European integration and the need to placate Russia’s security concerns. Russia still had military bases in support of secessionist provinces in Georgia and Moldova, as well as its naval base in Crimea.

Nation branding has become a widespread practice, involving the commodification and commercialization of national identities for the purpose of attracting tourism, foreign investment, or prestige events (Aronczyk Reference Aronczyk2013). The norms and practices of nation branding are managed by a trans-national expert elite. Nation branding is primarily aimed at foreign audiences: it is unclear to what extent nation-branding campaigns feed back into national identities at home. Most of the post-Soviet states have struggled to develop a national “brand” and establish some visibility for themselves within the international arena. Even such an apparently trivial achievement as entry into the Eurovision song contest has been a surprisingly important marker of global recognition (Graney Reference Graney2019). Estonia, Lithuania, and Russia joined Eurovision in 1994, followed later by Latvia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. Kazakhstan has not been allowed to join the European Broadcast Union – a precondition for entry to Eurovision. Russia went to great lengths in its quest for victory, embracing the quirky cultural norms of the competition, and finally winning in 2008 (Johnson Reference Johnson2014). Azerbaijan, Estonia, and Latvia have also won once — and Ukraine thrice.

All of these states – from Armenia to Uzbekistan – have an active policy of engagement with their diasporic communities, in part because the diaspora often provides a platform for opposition to the authoritarian regimes at home. The pre-existing Baltic, Armenian, and Ukrainian diasporas in the West each became actively involved in the nation-building process in their ancestral homeland.

Race, Class, and Gender

Contemporary American sociology revolves around the intersectionality of race, class, and gender (Mccall Reference Mccall and Grabham2008). The academic literature on nation-building in the post-Soviet space concentrates on top-down, state-led nation-building strategies and pays little attention to these sociological categories, with some notable exceptions (Isaacs and Polese Reference Isaacs and Polese2016). This reflects the state-centric bias of most of the literature on post-communist democratic and market transitions.

It also reflects the way nationalist politics is practiced in the region. Soviet Marxism had a well-articulated theory of the dynamics of race, class, and gender in modern society – and post-Soviet political actors had no interest in maintaining the Soviet understanding of those categories. Western-based organizations promoted their own views about how to handle race (xenophobia is out, multicultural tolerance is in); class (civil society is good, class struggle is bad); and gender (women deserve full equality with men). While liberals in the region welcomed these ideas, most of the mainstream intellectuals and policymakers reacted against Western ideological exports, rejecting terms like “multiculturalism” and “feminism.”

Gender

Gender has always played a central role in narratives of national identity – though it was largely absent from some of the core works in the field, such as the classic texts of Benedict Anderson and Ernest Gellner. As the Soviets created a masculine, secular, and socialist public sphere, national traditions were often seen as being preserved in the predominantly female private sphere (Cleuziou and Direnberger Reference Cleuziou and Direnberger2016). In the post-Soviet context the return of “traditional” gender norms has been central. Nation-building is seen as a man’s business, with male leaders shouldering the burden of defending the nation in war and shaping its identity in peace. Similar patterns have played out in most of the post-Soviet countries: the political marginalization of women, disdain for Western feminism, and the development of male leader cults (though few have reached the level of performative machismo that surrounds Vladimir Putin).

Women are portrayed as vulnerable members of society that need to be protected from external threats, and as mothers whose capacity to bear children guarantees the future of the nation (Yuval-Davis Reference Yuval-Davis1997; Mayer Reference Mayer2012). In the private sphere, women are subordinate to the husband who is the breadwinner and head of the household. The female body is treated as symbolic of the nation, but this can also be used to legitimize male attacks on women who are seen as dressing inappropriately (Suyarkulova Reference Suyarkulova2016). With declining populations due to out-migration and below-replacement birth rates, most of the post-Soviet states have adopted pro-natalist family policies, such as cash stipends for mothers. These policies have had only limited success in reversing declining birth rates due to economic constraints and resistance from women, but they dominate national narratives about gender roles.

Female politicians are thin on the ground, though again, the Baltics are something of an exception. Lithuania had a female prime minister after it declared independence in 1990, Kazimira Prunskienė. Latvia was the first post-Soviet country to see a female president, Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga (1999–2007), followed by Lithuania’s Dalia Grybauskaitė in 2009 and Estonia’s Kersti Kaljulaid in 2016. Latvia also had a woman prime minister, Laimdota Straujuma (2014–16). Outside the Baltics, Roza Otunbayeva was briefly president of Kyrgyzstan in 2010–11. Moldova saw Zinaida Greceanîi as prime minister (2008–09) and Maia Sandu was prime minister in 2019 and then president since 2020. In Ukraine, Yulia Tymoshenko made a fortune in gas trading, founded her own party, and rose to the post of prime minister (in 2005 and again from 2007–10).

Race

Race is not a category that is widely used in post-Soviet politics and society, in part because Soviet ideology had downplayed its relevance for Soviet society (Zakharov Reference Zakharov2015; Zakahrov and Law Reference Zakharov and Law2016). In post-Soviet Russia, casual racism has been fairly widespread, with polls in Russia showing the strongest hostility towards the Roma, Chechens, and other peoples of the Caucasus (Alexeev and Hale Reference Alexeev, Hale, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2016). As Russia’s economy picked up in the 2000s, large numbers of migrants came to Russia from Central Asia and the Caucasus. They number from 10–15 million people (7–10% of the total population), the second largest group of immigrants in the world after the US. Their presence was resented by many residents, and they were sometimes assaulted by skinheads and nationalist groups. The Kremlin experimented with using radical Russian nationalists to undercut the liberal opposition, but since 2011 the main thrust of official policy has been to crack down on extremist groups and ban hate speech from the media (Verkhovsky Reference Verkhovsky, Kolstø and Blakkisrud2017). Outside of Russia, in the other post-Soviet states, the main “racial” divide is between Slavs – perceived as migrants and colonists – and native peoples. Most of the ethnic Russians who were living in the Caucasus and Central Asia migrated to Russia in the 1990s.

Class

For thinkers such as Ernest Gellner and Eric Hobsbawm, class featured prominently in their explanation for the rise of nationalism. Nationalism was a tool used by the bourgeoisie to divide and distract the workers – or a rallying cry for revolutionaries to forge an anti-colonial movement. But in the post-Soviet world, after 75 years of propaganda about the virtues of the “workers’ and peasants’ state,” there was no enthusiasm for social mobilization along class lines. The newly-formed, mostly authoritarian states were keen to nip labor mobilization in the bud through repression and cooptation (Crowley Reference Crowley2015). Even in the democratic countries, labor unions have been weak. In the Baltic states, as in Poland and the Czech Republic, liberals argued that neoliberal market reform – including a weakening of labor rights – would facilitate a “return to Europe” and a more prosperous future. In Russia and most of the other post-Soviet states, the new class of capitalist oligarchs was easily able to suppress efforts to build a labor movement.

The class basis of post-Soviet nation-building was concentrated in the ranks of ruling elites, state officials, intellectuals, and business groups who were dependent on state sponsorship. Given globalization, all these countries found themselves dependent on trade with foreign partners and the acceptance of foreign technology and investment. This could lead to political tensions, with sporadic protests against exploitation of local workers by foreign investors in the oil fields of Kazakhstan, or against Canada’s Centerra which owned Kyrgyzstan’s Kuntor gold mine.

The upsurge of populism in recent years, from Latin America to Europe, has shown the potential for nationalism to serve as a rallying cry for socially marginal groups: workers and farmers threatened by international competition and the middle classes who fear a similar fate. It has been a powerful force in Central Europe, notably Hungary and Poland. But populism has not really surfaced in the former Soviet Union, because electoral competition is limited, with parties structured along clientelist rather than programmatic lines, and parties and mass media controlled by a narrow oligarchic elite (March Reference March and Kaltwasser2017).

Rather than populism, elitism is the order of the day. It is common to see oligarchs leverage their wealth into political power, using nationalist rhetoric to bolster their legitimacy, while constructing clientelist networks. Their self-interested pursuit of wealth and power weakens rather than strengthens their respective nations. Bidzina Ivanishvili made a fortune in Russia estimated at $6.4 billion, then returned to his native Georgia and entered politics. His Georgian Dream coalition won the 2012 parliamentary election: Ivanishvili served as prime minister for a year and operated as the power behind the throne thereafter. Vladimir Plahotniuc was the eminence grise of Moldovan politics: he made a $2 billion fortune in energy and banking before entering politics in 2011. In Ukraine, chocolate magnate Petro Poroshenko was elected to the presidency in 2014: he opened the country to the West but presided over a shifting coalition of rent-seeking oligarchs that failed to deliver substantial reforms. In the face of waning popular support, Poroshenko increased his nationalist, anti-Russian rhetoric, but nevertheless went down to a crushing defeat in the May 2019 presidential election at the hands of a political neophyte, the television comedian Viktor Zelenskiy. Zelenskiy’s success can be seen as one of the few examples of the populist wave in the Soviet space. And it frightened the Kremlin.

The Salient Features of the Individual Countries

Russia

Russia formed the core of the Soviet Union, and the Russian Federation emerged with the most powerful state apparatus of all the post-Soviet states. Nevertheless, Russia was also torn by competing interpretations of national identity and the appropriate ideological foundation for the new/old Russian state. The very proximity of Russian and Soviet identities made it difficult for Russians to define themselves in opposition to their Soviet past. Russia inherited from the Soviet Union a multi-ethnic federal structure and global power worldview which made it difficult for Russian elites to adopt the strategy of most of the other post-Soviet states – that of a “nationalizing” state built around the titular nationality and in opposition to the Soviet past.

There were at least four competing visions of the appropriate frame for the Russian Federation: a multi-national state, an ethnic state (“Russia for the Russians”), a civic state (neutral as to ethnicity), and an imperial state (ruling over other peoples and territories). The multi-ethnic and civic views were dominant in the Russian government’s thinking in the 1990s – though these two approaches contradicted each other in crucial respects, such as the special status of the ethnically-designated republics within the Federation (which included, in the case of Tatarstan, effective exemption from federal taxation and military conscription).

After coming to power in 2000, Vladimir Putin focused on strengthening central state power and rebuilding the economy, and he oversaw a cautious reformulation of Russian identity. Blakkisrud (Reference Blakkisrud2022) argues that “Putin’s recipe echoed the Soviet approach: a civic nation model, with significant cultural and political rights to ethnic non-Russians, held together by a broad set of common values and traditions.” At the same time, Putin was “purposefully ambiguous” (Shevel Reference Shevel2011) about where the borders of the Russian state should lie, and which groups belonged within it. The state invested heavily in patriotic education and the promotion of new symbols, while pushing rival visions of Russia’s national narrative to the margins of the political system. After Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, he put a new emphasis on the ethnic component in Russian identity, including a prominent role for the Orthodox Church. This trend accelerated after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Moscow stresses continuity with the “1,000 year history” of the Russian state, while elevating the Soviet victory of 1945 into a virtual state religion. Moscow has increased the pressure on non-Russian ethnic groups to assimilate to that core culture (with some exceptions, notably Chechnya). In July 2021, Putin published an essay in which he claimed that the Ukrainian nation was an artificial entity and that Russians and Ukrainians were really one people, laying the groundwork for the invasion that he launched in February 2022 (Putin Reference Putin2021). This was a radical break with Russian policy of the previous 30 years – and with Soviet practice.

Ukraine

In Ukraine distinct regional identities overlapped with competing views of international identification: with Russia or with Europe. These cleavages mapped onto differing patterns of language use and competing visions of the appropriate language policy for the new state: Ukrainization versus tolerance for the continuing use of Russian (Kulyk Reference Kulyk2018). There was controversy over how to narrate painful episodes in Ukrainian history, such as the 1930s famine (Holodomor) and World War II. For the first 23 years of post-independence, the balance between these competing historical and geopolitical narratives was preserved thanks to patronage bargaining between rival segments of Ukraine’s political and economic elites: in a sense, corruption served as glue preserving national unity (Darden Reference Darden2008). However, this balancing act was shattered by the 2013–14 political crisis. Putin persuaded President Viktor Yanukovich not to sign an association agreement with the EU, which led to his overthrow in the Maidan revolution. Russia responded by annexing Crimea and organizing an insurrection in Donbas. Paradoxically, this resulted in a stronger consensus in the rest of Ukraine for a new, civic national identity outside the Russian sphere of influence. In most of the post-Soviet space, nationalism has served as a tool to reinforce authoritarian regimes. But in Ukraine, it has helped keep the country on a democratic path, through the revolutions of 2004 and 2014.

Belarus

In Belarus Aleksandr Lukashenka used national identity as one of the tools to build a powerful, centralized state. Belarus is perhaps the only case in the post-Soviet region where there has been a radical change of course in nation-building strategy. In 1991–94 a new “nationalizing state” in Minsk promoted pre-Soviet Belarusian identity in opposition to the Soviet “Other” – including revival of the Belarusian language. However, after Lukashenka took power in 1994, this approach gave way to a radically different narrative in which the Soviet era was idealized as a golden age and Russian was restored as an official language alongside Belarusian. Nelly Bekus (Reference Bekus2022) notes that “Lukashenka’s language policy made Belarus a unique post-Soviet republic where political independence led to a step toward further Russification.” This policy worked in synergy with Lukashenka’s pro-Moscow diplomatic stance and a political economy dependent on subsidized oil and gas imports from Russia. However, the mass protests that greeted the rigged presidential election of August 2020 showed that a large proportion of the people rejected Lukashenka’s rule. They proposed a different national narrative, one that reflected Belarusian cultural traditions and respect for human rights, rather than Lukashenka’s Soviet nostalgia.

Moldova

In Moldova, society was divided over whether to pursue the path of EU integration, in part because of the problem of separatism in Transnistria, an ethnically mixed but predominantly Russian-speaking enclave on the left bank of the Dniester (Crowther Reference Crowther2022). Transnistria has survived thanks to Russian support, and Russia’s insistence on maintaining a military base in the territory scuppered a succession of peace plans. In the meantime, a desperate economic situation and institutionalized corruption undermined state capacity in Moldova, leaving a polarized and self-centered political elite that has been unable to embark on any effective nation-building initiatives. In the democracy indices, Moldova is second only to the Baltic states in the post-Soviet space (table 1). But this is a sobering reminder that electoral contestation alone does not a democracy make, nor does it guarantee that a solution will be found to ethno-political polarization. Pluralism theory posits the virtues of cross-cutting cleavages amongst the electorate, but in the case of Moldova the persistence of ethno-cultural divisions over Transnistria has undermined efforts to form an effective anti-corruption bloc.

Estonia

Estonia is often hailed as the most successful nation-building project in the post-Soviet space. After regaining its lost independence, Estonia moved quickly to introduce exclusionary citizenship laws and promote Estonian language. Fears of political disruption from the 30% Russian minority, most of whom were denied citizenship, did not materialize. Vello Pettai (Reference Pettai2019, 2021) explains that rather than dwell exclusively on the injustices of the past, Estonian governments focused on looking to the future, pursuing EU entry, and embracing e-government and high-tech industries. The proportion of residents without Estonian citizenship has fallen below 15% and will continue to decline as the older generation dies off. However, non-ethnic Estonians do not have their own parties and there are few minority politicians in leading positions. The main challenge now is demographic decline: due to the low birth rate and out-migration for jobs in the EU, Estonia’s population has fallen by 13% since independence.

Latvia

Latvia, like Estonia, successfully re-established its sovereignty after 50 years of Soviet rule. Despite a fairly exclusionary citizenship policy, it managed to integrate its minority residents without triggering a political crisis. Rasma Karklins (Reference Karklins2021) argues that “essentialist” and binary approaches to ethnicity do not capture the complexity of inter-ethnic relations in politics, business, and daily life. The proportion of non-citizens fell from 29% in 1995 to 13% in 2014. Still, according to the 2011 census, 37% of respondents spoke Russian at home (and watched Russian TV channels), though 77% of non-Latvians claim some proficiency in the Latvian language. Minorities have been active participants in the political system, with Riga electing an ethnic Russian mayor in 2009. The 2014 Ukraine crisis brought fears that Latvia could be the next target of Moscow’s revanchism, with polls showing that 40% of Latvia’s Russian-speakers approved Russia’s annexation of Crimea. As in Estonia, demographic decline is a concern, with the population dropping 27% since 1991.

Lithuania

Lithuania’s pursuit of independence played a leading role in the break-up of the Soviet Union. The high proportion of ethnic Lithuanians at the time of independence (80%, compared to 62% of titulars in Estonia and 52% in Latvia) meant that Lithuania felt able to immediately grant citizenship to all residents in a 1989 law (Klumbytė and Šliavaitė Reference Klumbytė and Šliavaitė2021). Since independence, Lithuanian has been promoted as the state language, leading to some complaints from the Polish- and Russian-speaking minorities. Likewise, the official historical account of Lithuanian victimization at the hands of the Soviet state does not always accord with the historical narratives of the minority groups. Demographic decline due to the low birth rate and high out-migration has seen the Lithuanian population shrink by 27% since 1991.

Azerbaijan

Along with its neighbors in the south Caucasus, Azerbaijan experienced a nationalist mobilization in 1988–1991 – but unlike in Georgia or Armenia, the nationalist counter-elite were unable to secure control of the new state (Broers and Mahmudlu Reference Broers and Mahmudlu2022). The ex-communist elite in Baku reinvented itself at the head of a nationalizing state – helped along by the influx of oil wealth – while the Aliyev family concentrated political power in its own hands. Nation-building in Azerbaijan was powerfully shaped by the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh and the presence of Azerbaijani communities in neighboring states, notably Iran (home to over 15 million Azerbaijanis). Azerbaijan’s nation-building has been ostensibly civic and multicultural, respecting the rights of ethnic minorities such as the Lezgins. Partly this was done to win international support for efforts to regain Karabakh, and partly to justify the marginalization of the Azerbaijani nationalist opposition. Paradoxically, it was countries like Azerbaijan – from which most of the Russian-speaking minorities had fled – that were most at ease in tolerating the use of the Russian language. Still, Azerbaijan has struggled to maintain a balance between competing pressures, sitting at the intersection of secularism and Islamism, and pro-Western and pro-Russian strategic relationships. Azerbaijan won a decisive victory over Armenian forces in November 2020 (thanks in large part to military assistance from Turkey), regaining control over most of the territories lost in 1994, and this will presumably further consolidate the ruling political regime. The insertion of 2,000 Russian peacekeepers at the end of the 2020 war gave Armenians a slender hope of retaining a presence in Karabakh.

Armenia

Armenians are an ancient people, adopting Christianity as their official religion in 301 CE. Along with the Georgians, they are one of the few nations in the world to have preserved their own unique script. The 1915 genocide is a powerful focal point for Armenian identity. The achievement of independence in 1991 was overshadowed by the ongoing conflict with Azerbaijan over the majority-Armenian territory of Karabagh. By the late 1990s the “Karabagh party” had come to dominate Armenian politics, and Armenia strayed from the democratic path. Another complication was the role of the diaspora: only three million of the estimated 11 million Armenians in the world live in Armenia. These factors undermined efforts to create a more inclusive, civic identity for the new Armenian state, instead favoring politicians who espoused a more ethnic approach: a nation with a mission. The “Velvet Revolution” of 2018 propelled opposition leader Nikol Pashinyan to power and revived hopes in a democratic transformation. It was not to be: defeat in the 2020 Karabagh war weakened the Pashinyan leadership (Derluguian Reference Derluguian2021).

Georgia

Rejection of Russian and Soviet imperialism has been central to Georgia’s national revival, rooted in its distinctive language and culture. However, the ethnic minorities in Abkhazia and South Ossetia resisted the imposition of Georgian rule, winning de facto independence in 1993 thanks to military support from Russia. The desire to win back control of those provinces was an important factor behind the Rose Revolution of 2003, which bought to power Mikheil Saakashvili, who tried to tackle corruption and align Georgia with the West (Metreveli Reference Metreveli2016). This is another example of the synergy between nationalism and democracy. However, Saakashvili’s forceful policies culminated in the 2008 war with Russia, and defeat. The Georgian Orthodox Church emerged as a powerful actor shaping Georgian identity, and the national identity narrative has become more focused on ethnic Georgian identity, causing some tension with the Armenian and Azerbaijani minorities. Economic disruption due to the political conflicts and economic isolation led to a 26% drop in population since 1991.

Central Asia

Many observers doubted the viability of the nation-building projects in Central Asia (Roy Reference Roy2007). None of the region’s nations had experienced self-rule in the modern era, and their Communist rulers were the last to accept the Soviet collapse in the waning months of 1991. However, after independence, the incumbent Communist leaders quickly rebranded themselves as nation-builders, and were able to create functioning regimes that have become accepted participants in the international system. Rulers legitimized the repression of opposition by insisting that national unity required political unity. The region’s leaders faced many common challenges, from the threat of radical Islam to the emigration of much of the labor force (mainly to Russia), but the “nationalization” of the region’s political systems post-1991 stymied regional cooperation. The borders that Stalin drew in the 1920s–30s delimiting the region into five republics left many ethnic minorities living outside their titular homeland, leading to occasional outbursts of violence, particularly in Kyrgyzstan. Despite this, none of the Central Asian states have shown any stomach for challenging their mutual borders post-independence. Remittances from the migrants working in Russia represent a substantial source of income for the poorer republics of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Kazakhstan

The nation-building strategy of Kazakhstan faced a challenge unique in Central Asia because non-Kazakhs made up more than half the population at the time of independence. President Nursultan Nazarbaev cultivated ethnic pride for Kazakhs while at the same time promoting an inclusive, civic Eurasian identity to reassure the Slavic population that there was a place for them (Dave Reference Dave2021). Nazarbaev pursued a multi-vector diplomatic strategy: welcoming Western investment while joining Russian-led regional security and trade organizations (the Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Eurasian Economic Union). This strategy succeeded, in part thanks to the influx of revenue from oil and other mineral exports, which caused Kazakhstan’s per capita GDP to draw level with that of Russia. The state was able to increase living standards and invest in expensive prestige projects such as the construction of a new capital, Astana. Ethnic Kazakhs living in Mongolia, China, and in Central Asia were encouraged to move to Kazakhstan, and over one million did so, helping to boost the titular share of the population from 40% in 1989 to 63% in 2009 (Demoskop Weekly 2022). Disagreements over the history of Russian colonialism, or the need to boost the status of the Kazakh language, have been carefully managed. The Russian language continues to be widely used, and Kazakh is still written in Cyrillic script – while other countries like Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan started the switch to Latin script soon after independence (Landau and Kellner-Heinkele Reference Landau Jacob and Kellner-Heinkele2001).

Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan, under the authoritarian rule of Islam Karimov (1991–2016) the Islamist and nationalist opposition were crushed while the state promoted its own secular, teleological account of Uzbek identity, stretching back into antiquity (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2018). Much of this historical meta-narrative had its roots in Soviet era ethnology, while at the same time Russian colonialism was condemned. Rejection of Western values – and of radical Islam – was also part of the package. Karimov promoted use of the Uzbek language but excluded any efforts to defend the rights of ethnic Uzbeks living outside the republic. Over time, the regime retreated into an isolationist posture, wary of the possible spill-over of instability from neighboring countries. The paternalistic political regime was bolstered by the maintenance of strong state controls over the economy. After Karimov’s death in 2016 there was a smooth transition to new president Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who launched moderate economic reforms while promising to strengthen the role of the Uzbek language and to promote a moderate “Enlightened Islam” in keeping with the nation’s traditions (Cornell and Zenn Reference Cornell and Zenn2018).

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan has struggled to create a unifying national narrative – a problem that goes beyond mere lack of resources or state capacity to knit together rival regional and ethnic elites (Huskey Reference Huskey2022). These failings were exemplified by the bloody uprisings of 2005 and 2010, fueled in part by tension between the northern and southern halves of the country (separated by a mountain range). Soviet Kyrgyzstan was ethnically diverse and heavily Russified. Post-1991 saw an exodus of Germans and ethnic Russians, who had formed a majority of the residents of the capital, Bishkek. The second city of Osh in the south saw bloody clashes in 1990 between Uzbek and Kyrgyz residents. In the 1990s, new tensions arose between Russified urban Kyrgyz and rural Kyrgyz who were moving into the cities. The first post-independence president Askar Akaev tried to pursue an inclusive, civic citizenship, albeit while promoting Kyrgyz identity; but under the southerner Kurmanbek Bakiev, who took power in 2005, policy took a more ethno-nationalist turn. Social tensions fueled Bakiev’s violent overthrow in 2010, which was followed by attacks on Uzbeks in the south. Likewise, President Sooronbay Jeenbekov was toppled by protests in 2020. Despite the state’s efforts to promote the Kyrgyz language, a third of school-leavers still take their graduating exams in Russian – in part because it is useful for the large numbers of young Kyrgyz headed to Russia for work.

Tajikistan

Soviet nation-building in Tajikistan had failed to overcome deep regional differences, which triggered a bloody civil war from 1992 to 1997. John Heathershaw and Kirill Nourzhanov (Reference Heathershaw and Nourzhanov2022) characterize the subsequent nation-building under the authoritarian ruler Emomali Rahmon as “soft ethno-nationalism.” Like elsewhere in Central Asia, the foundations of the post-independence Tajik national narrative were laid by Soviet-era historians, philologists, and ethnographers, who carved out a primordial, unilinear account of Tajik identity – under threat from the surrounding Turkic/Uzbek peoples. However, this cultural nationalism did not translate into political unity, and the brutality of the civil war led to a certain nostalgia for Soviet times. Tajiks now make up 84% of the population: most ethnic Russians emigrated, while half of the Uzbeks either left or re-identified as Tajiks (just as many of the Tajiks living in Uzbekistan were reclassified as Uzbeks). The radical Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan transformed itself into a more mainstream opposition party after the 1997 peace accord, but the party was banned and its leaders arrested in 2015.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan – like many other nations around the world – is a 20th century creation. Since 1991 the role of the Soviet Union in creating modern Turkmen identity has been downplayed: instead the country’s authoritarian leadership has promoted an extraordinary personality cult around the leader, embedded in a narrative of continuous, homogenous Turkmen identity going back to ancient times (since the prophet Noah!) (Peyrouse Reference Peyrouse2021). This pattern was forged under the “Father of the Turkmens” Saparmurat Niyazov, and continued after his death in 2006 under his successor Gurbangully Berdymukhamedov. Tribal identities were suppressed, while non-Turkmen ethnic minorities such as the Uzbeks and Russians were marginalized. Russian language teaching ceased and Russian media were barred. The state has maintained tight control of the economy, which revolves around natural gas exports. The building of a pipeline to China cut the dependence on Russia as an export route.

De Facto States

The break-up of the Soviet Union doubled the number of unrecognized, de facto states in the world. Abkhazia, Karabakh, South Ossetia, Transnistria, and the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics were added to the list (Dembinska Reference Dembinska2022). While the de facto states face common challenges, there are important differences between them. They vary in size of population: 50,000 in South Ossetia, 150,000 in Karabakh, 250,000 in Abkhazia, 475,000 in Transnistria, and over three million in Donetsk and Luhansk. Transnistria and Abkhazia are ethnically diverse, while Nagorno-Karabakh and South Ossetia are ethnically homogeneous and have strong ties with co-ethnics in a neighboring state. These entities are isolated and impoverished, and survived thanks to foreign sponsorship – Armenia backing Karabakh and Russia supporting the others. Within their own borders they have most of the attributes of a sovereign state, but they remain unrecognized by the international community – though Russia did take the step of recognizing South Ossetia and Abkhazia in the wake of the 2008 Georgian war. Given their precarious position, the de facto states work overtime in creating historical narratives to try to justify their existence as self-governing states, stressing the threat of cultural extinction at the hands of the adversary state, and the sacrifices involved in breaking free from their rule. The dogged pursuit of statehood by the de facto states testifies to the continuing relevance of the nationalist project.

Conclusion

The post-Soviet experience shows that the achievement of political sovereignty and freedom from a controlling imperial center does not guarantee a stable and prosperous future for the nation. The new states remain vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the global economy and great power politics, and the political legacy of decades of Soviet communism made them ill-prepared for a transition to democracy. The Baltic republics were lucky in quickly finding regional allies who helped them gain entry to the European Union and NATO, providing a degree of economic and military security which enabled competitive electoral democracies to take root. Moldova and the Caucasus republics were less fortunate: some of their ethnic minorities took up arms, and with Russian help those secessionist enclaves have become what seems to be a permanent feature of the geopolitical landscape. Oil has rescued Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan from economic stagnation, but has also facilitated the consolidation of authoritarian regimes. The fate of Ukraine – European partner or failed state? – hangs in the balance. And Russia itself, under sanctions from the West because of its invasion of Ukraine, faces an uncertain future given the concern that its political stability might unravel once Vladimir Putin leaves the political stage.

The newly-independent states followed a broadly similar template of nation-building, prioritizing the language of the titular nationality and crafting a new historical narrative to portray the nation as a community with collective loyalty and a shared past. Fully a generation has passed since the Soviet collapse: young adults now have no direct memories of the Soviet past or even of the economic hardships of the 1990s. The evidence is mixed, but there are some indications that they may be more tolerant, and more interested in democracy, than their parents and grandparents (Blum Reference Blum2007; Nikolayenko Reference Nikolayenko2017). But as yet we have few studies on generational differences in the politics of national identity in these states.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Ray Taras for his assistance in preparing this special issue.

Disclosures

None.