Introduction

This article explores the socio-emotional dimension of national belonging in post-Soviet neoliberal Latvia. It does so from the perspective of national pride, which is explained as a positive emotional attachment to a nation, is related to national identity (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006), and is essential for patriotism as “the degree of love for and pride in one’s nation – in essence, the degree of attachment to the nation” (Kosterman and Feschbach Reference Kosterman and Feshbach1989, 271). If national identity is an emotionally positive bond with a nation (Tajfel and Turner 1986, cited in Meitinger Reference Meitinger2018, 429), then national pride shapes the character of this bond (Scheff Reference Scheff1994, 3). Studies show that national pride is low in post-Soviet countries and Latvia particularly (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006; Fabrykant and Magun Reference Fabrykant, Magun, Grimm, Huddy, Schmidt and Seethaler2016; Fabrykant Reference Fabrykant2018; Vlachová Reference Vlachová2019). This especially refers to people’s pride in their countries’ socioeconomic and political attainment identified in surveys from the 1995–1996, 2003–2004, and 2013 waves of the International Social Study Program (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006; Fabrykant and Magun Reference Fabrykant, Magun, Grimm, Huddy, Schmidt and Seethaler2016; Fabrykant Reference Fabrykant2018). To some extent, this is related to “a large non-Latvian minority” and the fact that minorities tend to show weaker pride in countries’ achievements (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006, 128, 132); however, scholars recognize that this explanation is not complete (Smith and Kim, Reference Smith and Kim2006; Fabrykant Reference Fabrykant2018). This study seeks to provide an additional explanation of low national pride in post-Soviet Latvia.

In literature, national pride is usually seen as a unidirectional relationship where people feel (or do not feel) pride in various aspects of their country – for example, concerning a country’s democratic achievements, political achievements, or social security system, etc. (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006; Ha and Jang Reference Ha and Jang2015; Müller-Peters Reference Müller-Peters1998, 702; Hjerm Reference Hjerm2003, 416; Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg2012). This view is related mainly to the fact that many studies on national pride are quantitative and designed to ask how citizens feel about their country and various aspects of it. This unidirectional approach also appears in studies based on qualitative methods (Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg2012). This present study establishes national pride as a relational emotion based on the theories of social bond (Scheff Reference Scheff1994) and commitment (Lawler, Thye, and Yoon Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009). This perspective requires that understanding national pride is not enough to explore how people relate to their state. It is also necessary to understand how the states relate to their people, whether they recognize their state constituents and their needs and feel pride in them, and whether they shape social bonds among people.

Literature from the post-Soviet context (Ozoliņa Reference Ozoliņa2019; Sommers Reference Sommers2009, among others), as well as other contexts (Garni and Weyher Reference Garni and Weyher2013; Somers Reference Somers2008; among others), suggests that neoliberal transformations challenge commitment between the state and its constituents. To account for the national identity as a type of social bond mediated by emotions of national pride, I take the post-Soviet neoliberal context seriously. For this study, I define neoliberalism as a political economy regime that intends to “transfe[r] economic power and control from governments to private markets” (Centeno and Cohen Reference Centeno and Cohen2012, 318). Somers (Reference Somers2008) argues that the market intervenes between the state and citizens in ways that fundamentally transform the state-society relationship (e.g., 74–76). Citizens are expected to solve social issues not with the help of state institutions but individually through market means. In post-Soviet Latvia, neoliberal policy reforms and ideas were introduced in a more radical form than elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe (Bohle and Greskovits Reference Bohle and Greskovits2007; Aidukaite Reference Aidukaite, Cerami and Vanhuysse2009; Sommers Reference Sommers2009); therefore, it is critical to consider how this context relates to national identity.

Scholars have argued that “understanding national identity and national pride requires that we explore in greater depth the complexity of national pride in individuals’ lived experiences” (Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg2012, 149). Empirically, I combine the analysis of the post-Soviet civil discourse and in-depth exploration of the narratives of 59 emigrants who have left Latvia and emigrated to the West in the post-Soviet era. Through this analysis, I reveal that the Latvian state did not recognize Latvian nationals in terms of their socioeconomic hardships. The post-Soviet transformations and neoliberalization in Latvia worked in ways to “attune” the state leaders to Western states, institutions, experts, and businesses, but not so much to the state constituents or the people (cf. Ķešāne and Weyher Reference Ķešāne and Weyher2021). I argue that this emotional dynamic formed an insecure social bond between people and their state in post-Soviet Latvia, thus eroding an opportunity for national pride to flourish.

Relationship between National Pride and National Belonging

Theories on Social Bond and Commitment

A great deal has been written on historical roots, epistemologies, and the character of national identity (cf. Özkırımlı Reference Özkırımlı2010); therefore, in this article, I focus on the emotional mechanism of national identity. In essence, national identities “signify bonds of solidarity among members of communities” (Smith Reference Smith1991, 15). These social bonds generate a sense of community and commitment. Building on theories of social bond and commitment (Scheff Reference Scheff1994; Lawler, Thye, and Yoon Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009), I explain the state’s role in shaping social bonds between the people and the state and among the people as critical. Both theories reveal the meaning of pride for social bonds and its more durable form – commitment. Both theories seem to be particularly relevant in the Eastern European context since a recent study on national identity criteria for the Baltic populations reveals that “contrary to the still influential stereotype of eastern European nationalism as ethnic, national identity in the contemporary Baltics focuses […] on the criteria reflecting loyalty and commitment” (Fabrykant Reference Fabrykant2018, 22).

The sociologist Thomas Scheff (Reference Scheff1994) argued that emotions of pride and shame are “a key aspect of the bond,” where the first one “signals a secure bond” while the latter signals an insecure bond (3). Emotions related to pride are a sense of recognition and a feeling that one is worthy of being listened to, understood, or cared for. Emotions related to shame are humiliation and a sense of inferiority and no recognition. Social bonds are secure if a “balance between loyalty to the group and loyalty to the self, between interdependence and independence” is ensured (58). It means that a person is neither “alienated from self” (“engulfment”) nor “alienated from others” (“isolation”) (2). The emotion of pride signals an optimal balance between engulfment and isolation where parties are “emotionally and cognitively connected” (Scheff Reference Scheff1994, 61) and recognize and cherish each other as they are. Although any social bond, according to Scheff, contains emotions of pride and shame, solidarity and connectedness are fostered when pride – and not shame – prevails.

Similar observations are proposed by sociologists and economists Lawler, Thye, and Yoon (Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009) in their theory of social commitment. Like Scheff, they argue that mutually recognizing interactions generate positive feelings, such as pride toward self and gratitude toward others. In contrast, unsupportive interactions generate negative feelings, such as shame toward self and anger toward others (46). Unlike Scheff, they distinguish between two “fundamental” types of social bonds – instrumental or transactional and relational or affective social ties (26). They argue that affective ties may develop in a situation of repeated positive instrumental ties where a sense of recognition and pride is present. Instrumental ties are insufficient to produce social commitment since instrumental ties break apart in a situation of better returns or benefits elsewhere (23–26). On the contrary, repeated positive instrumental ties foster affective ties and no willingness to quit. Affective ties are crucial for social commitment and loyalty to form. Affective ties mean that a relationship becomes of value on its own, irrespective of the amount of benefit (23–26). A person wants to be part of an organization because it feels good.

The theory of social commitment explains two conditions when social interactions “generate positive or negative sentiment about larger (macro) social groups or units” (Lawler, Thye, and Yoon Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009, xi), including nations (chp. 9). People relate their individually felt emotion to a group if this group, be it a firm or a nation, establishes “a joint task” (“structural condition”), which then further “generates a sense of shared responsibility” among members of a group (“subjective condition”) (10, 57–58). This theory predicts that the person-to-group commitments that bring positive outcomes foster pride in the group’s achievements (65–67). Both theories can help to explain why surveys identify low national pride in political and economic achievement in Latvia.

National Identity as a Social Bond

That people do not feel pride in their nation’s political and economic achievement may result from an insecure national bond steered by the weak state-society bond. The neoliberal context added to this insecurity. According to the social bond theory, national identity will shape as a secure social bond if it does not confront a person’s other identities (no engulfment) and if the state is present in the lives of individuals (no isolation). If the state denies social protection for the needy and does not recognize them and their needs, they may not be able to fulfill their other identities (engulfment), for example, as a parent or a worker. Scheff, for example, referred to the general social conditions that shaped national identity as an insecure social bond at the time of his writing. He underlined the danger of extreme individualism by writing that “the ideology of extreme individualism idealizes isolation, thereby disguising and denying the need for social bonds” (Scheff Reference Scheff1994, 57). Although Scheff did not specifically refer to the neoliberal order, it is widely recognized today in academia that “neoliberal scripts” promote extreme individualism (Lamont Reference Lamont2019). Instead of relying on the states as guardians, people are socialized to fulfill their needs through markets and market competition. This may alienate people from the state (isolation) since their need for it and its presence in people’s lives become less pronounced. Nevertheless, this may also alienate people from the self (engulfment) since, under market conditions and competition, it becomes harder to realize the self. In this situation, people may rely on each other more. Market conditions and competition, however, may isolate people from each other too.

In contrast to Scheff, the theory of social commitment (Lawler, Thye, and Yoon Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009) reveals prospects for nationalism and associated sentiments today in a more positive light. In this theory, the nation and particularly the state as the sole guardian of the nation “shape the vitality of groups and an individual’s commitment to them through the ways in which they build hierarchies, allocate tasks, and shape identities” (Illouz Reference Illouz2011, 1673). Authors of the theory conceptualize two conditions under which strong affective ties in a nation are nurtured. The state needs to provide “salience or immediacy” for citizens and to serve as “a source of collective efficacy” (Lawler, Thye, and Yoon Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009, e.g., 152–153, 165). The former means that the state is present in the life of individuals. Authors argue that a “minimum threshold of salience is probably required for nationalist sentiments because the state unit must be salient as a social object ‘out there’ before people can attribute their feelings to it” (154). The “collective efficacy” means that the state has to ensure joint activity and a related sense of shared responsibility for its people, which results in such common goods as “security, protection or social welfare” (153–154, 165). They also emphasize that “if people have a greater sense of shared responsibility at the state level, the state’s salience and efficacy should have stronger effects on nationalist sentiments” (163). In that case, people feel a positive attachment to their state and will feel proud of it and its achievements. In my empirical data analysis, firstly, I focus on how the state-society relationship unfolded in a period when the state formed new democratic relationships with its nationals and whether the state generated a sense of salience and collective efficacy. Secondly, I focus on how people experienced and perceived the state regarding salience and collective efficacy. At an abstract level, I understand the state as a political elite and bureaucrats, as well as the institutions they represent. However, when I demonstrate the argument through empirical examples, concrete actors and institutions are uncovered to fill these terms with more nuance.

Somers’s (Reference Somers2008) writing on neoliberalism suggests that the two conditions (the state as salient to people and the state as the source of collective efficacy) identified in the theory of social commitment may be compromised under neoliberalism. This may further impede formation of national sentiments and pride within the society. Within the neoliberal order, individual responsibility is emphasized over a shared one, the demise of the welfare state further undermines the idea of collective efficacy, and financial and economic globalization impedes collective efforts for attaining collective results in nations. Lawler, Thye, and Yoon (Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009), comparing cross-national data from 1995 and 2003, found that people remain attached to their country despite globalization. Latvia, however, stood out as a country where people’s attachment to their country has dropped (156–159). It does not fit with the general findings of Lawler, Thye, and Yoon (Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009) that the loss of a sense of national community is a “myth” (197). This exception resonates well with the low national pride this study seeks to explain. More in-depth exploration of the Latvian case I offer may address criticism of this theory as not paying “attention to the dark side of affect and emotion” (Molm Reference Molm2012, 185). The state-society bond at the base of national identity or national sentiments in Latvia has been sustained by a lack of recognition, humiliation, resentment, and anger.

The theory of social commitment is also criticized for not taking into account “growing inequality and increasing divisions in political beliefs and values” (Molm Reference Molm2012, 185) and for seeing emotion as an independent force of social commitment (Illouz Reference Illouz2011). Illouz (Reference Illouz2011), building on the ideas of Durkheim, wrote that “affective commitment and responsibility can be generated only when a sense of moral order is produced, and this order cannot be separated from cultural structures, from what people believe in, and how belief is cognized and institutionalized” (1674). In the methodology section, I address this criticism by suggesting identification of the cultural structure or “symbolic codes” against which the state-society bond was formed. Based on the empirical data analysis, I will argue that the state-society bond in post-Soviet neoliberal Latvia formed as insecure, eroding an opportunity for national pride to flourish. In what follows, I briefly explain the post-Soviet neoliberal transformations as an important socio-historical context to consider when reading the data.

The Post-Soviet and Neoliberal Context for National Pride

Besides Gorbachev’s perestroika and stagnating Soviet economy, important bottom-up events led to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of Latvia. Several scholarly works point out that social movements were crucial for the independence of Latvia (e.g., Eglitis Reference Eglitis2002; Karklins Reference Karklins1994). Cultural social movements began in the 1970s, while environmental and human rights-oriented social movements gained prominence in the mid-1980s. They all aspired to transform the existing Soviet order. All these movements contributed to the empowerment of Latvian society, gave a conviction that true independence could be achieved, and provided a sense of shared responsibility for independence. This was a moment of collective pride when, in the spring of 1990, the Popular Front won the Supreme Soviet Elections and soon voted for independence.

The future political leadership of the state was facilitated and supported through these bottom-up processes. Pro-independence social movements encouraged the formation of political organizations whose leadership later became the political elite of the reestablished state of Latvia. Eglitis (Reference Eglitis2002) argues that “formal organizations in Latvia [at the end of the 1980s] operated to unite an already existing field of opposition movements under a shared frame of protest, to broaden the oppositions appeal and scope, and to strengthen the [independence] movement to extend its power from the civic arena to institutions of governance” (47). These movements created opportunities for forming a strong social bond and commitment between the people and the representatives or political leadership of the reestablished state.

However, along with the processes providing an opportunity for positive and affective state-society ties to be formed, neoliberalization took place. It fostered socioeconomic and cultural conditions, which apparently compromised the prospects for forming strong positive state-society ties. Appel and Orenstein (Reference Appel and Orenstein2016) write that in the 1980s and 1990s, “leading Western governments and international organizations were dominated by a neoliberal policy agenda, and they held the resources and mechanisms to export these ideas to the rest of the world” (317). Western experts representing agencies such as the IMF, World Bank, the European Union, the OECD, and various think tanks also advised the neoliberal agenda to the post-Communist governments (Appel and Orenstein Reference Appel and Orenstein2016, 318). The adoption of neoliberalism in Eastern Europe was so “rapid” because Eastern European economists, through their interactions with American economists during the Soviet era, already learned to see their “socialist econom[ies] as chaotic, inefficient, and in need of shock therapy” (Bockman and Eyal Reference Bockman and Eyal2002, 338). The post-Communist ruling elite thus followed the neoliberal agenda, prioritized the swift integration of their countries into the global economy, and tried to improve the national economy by attracting foreign capital (Appel and Orenstein Reference Appel and Orenstein2016). To support or legitimize “neoliberal politics and new configurations of inequalities,” the Soviet legacy or “the socialist past” was symbolically kept “alive in public discourse – almost three decades after its end” (cf. Chelcea and Druţǎ, Reference Chelcea and Druţǎ2016, 522). For instance, social claims often got rejected as Soviet inertia, as a wish for the caring hand of the Soviet state, thus precluding the opportunity to critically discuss issues of inequality and injustice.

Compared with other Eastern and Central European countries, the Baltic countries adopted neoliberalism in a “radical and uncompromising fashion” (Bohle and Greskovits Reference Bohle and Greskovits2007, 445; Sommers Reference Sommers2009; Eglitis and Lāce Reference Eglitis and Lāce2009). Compared to the two other Baltic countries, Latvia enforced “some of the most neoliberal policies in order to attract foreign direct investment” (Aidukaite Reference Aidukaite, Cerami and Vanhuysse2009, 110). This situation can partially be attributed to the fact that the independence movements did not envision what type of state they foresaw (Eglitis Reference Eglitis2002). Possibly, the lack of vision made the Latvian state political leadership more susceptible to radical neoliberal reforms advised by Western experts. Appel and Orenstein (Reference Appel and Orenstein2016) argue that such radicalism was also the result of global competition or “competitive signaling” to attract foreign investments. In their view, adopting neoliberal ideas and policies was also necessary if these countries wanted to be accepted by the West and earn EU membership. For example, to gain access to the EU, Latvia had to reduce its agricultural tariffs and facilitate the privatization of large sectors of the national economy, such as telecommunications and energy (Appel and Orenstein Reference Appel and Orenstein2016, 320). The trade liberalization prescribed by the Washington Consensus rendered Latvian producers and farmers vulnerable to global competition. Neoliberal principles also required austere policies (Aidukaite Reference Aidukaite, Cerami and Vanhuysse2009; Sommers Reference Sommers2009). Austerity negatively affected such sectors as medicine, education, and social aid to the needy.

A year after independence was regained, discontent and concerns within the society about the deteriorating socioeconomic conditions and the course of economic development Latvia had chosen were already common (Nissinen Reference Nissinen1999, table 11.1, 11.2). The increase in poverty and inequality (Eglitis and Lāce Reference Eglitis and Lāce2009) led to grievances against the political elite and the socioeconomic strategies of development it had chosen. The trust in the parliament decreased (Zepa Reference Zepa, Loftsson and Choe2001). Emigration to the more developed Western countries was one way disappointment with the state practices was resolved. From 2000 to 2014, 10.9% of the population emigrated to live and work abroad (Hazans Reference Hazans and Mieriņa2015, 22). Recent surveys reveal that “only 63% of emigrants felt closely or very closely attached to Latvia” (Koroļeva Reference Koroļeva, Kaša and Mieriņa2019, 75), while 28% of the emigrants displayed a very low sense of belonging to their home state or felt it was “rejecting” them (Koroļeva Reference Koroļeva, Kaša and Mieriņa2019, 76, table 4.3). This latter group showed “no trust at all in the Latvian government or the Latvian police or courts, yet [had] comparatively high levels of trust in the host country’s government” (79). Nevertheless, those who still felt belonging to Latvia also showed lower trust in the Latvian government than in their host countries’ governments (77). This certainly suggests weak state-society bonds in Latvia.

Method

The data for this article were collected to explain the state-society relationships in the context of high emigration (Ķešāne Reference Ķešāne2016) and not national pride per se. The theoretical lens of this article indicates that what is at stake for national pride is the character of the state-society bond, and therefore the original data fits well. Specifically, I combine the analysis of the post-Soviet civil discourse (1993–2000) with the narratives of post-Soviet emigrants to the West. Out of 59 respondents, 6 left Latvia from 1993 to 1999, 32 left between 2000 and 2003, 9 left between 2004 and 2006, and 12 left after 2008. The analysis of the civil discourse allows us to see how the state-society bond and relationships among people were shaped discursively, while the analysis of emigrants’ narratives helps to see how these bonds were experienced and perceived by the people.

Civil discourse here is understood as a representation of “conversation” (Alexander Reference Alexander2006) among members of the state, including among politicians and journalists and between politicians and citizens. This conversation or communication mainly occurs in mass media (Alexander Reference Alexander2006, 5). The civil discourse may illustrate the dominant and often competing ideas on which the state is rebuilt, how these ideas correspond to the particular loyalties of the state toward the people and various other social organizations (e.g., national, global/international bodies), and how this has influenced the relationship between the state and the people and among the people. Individual experiences and narratives are affected by civil discourse (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz1992, 505).

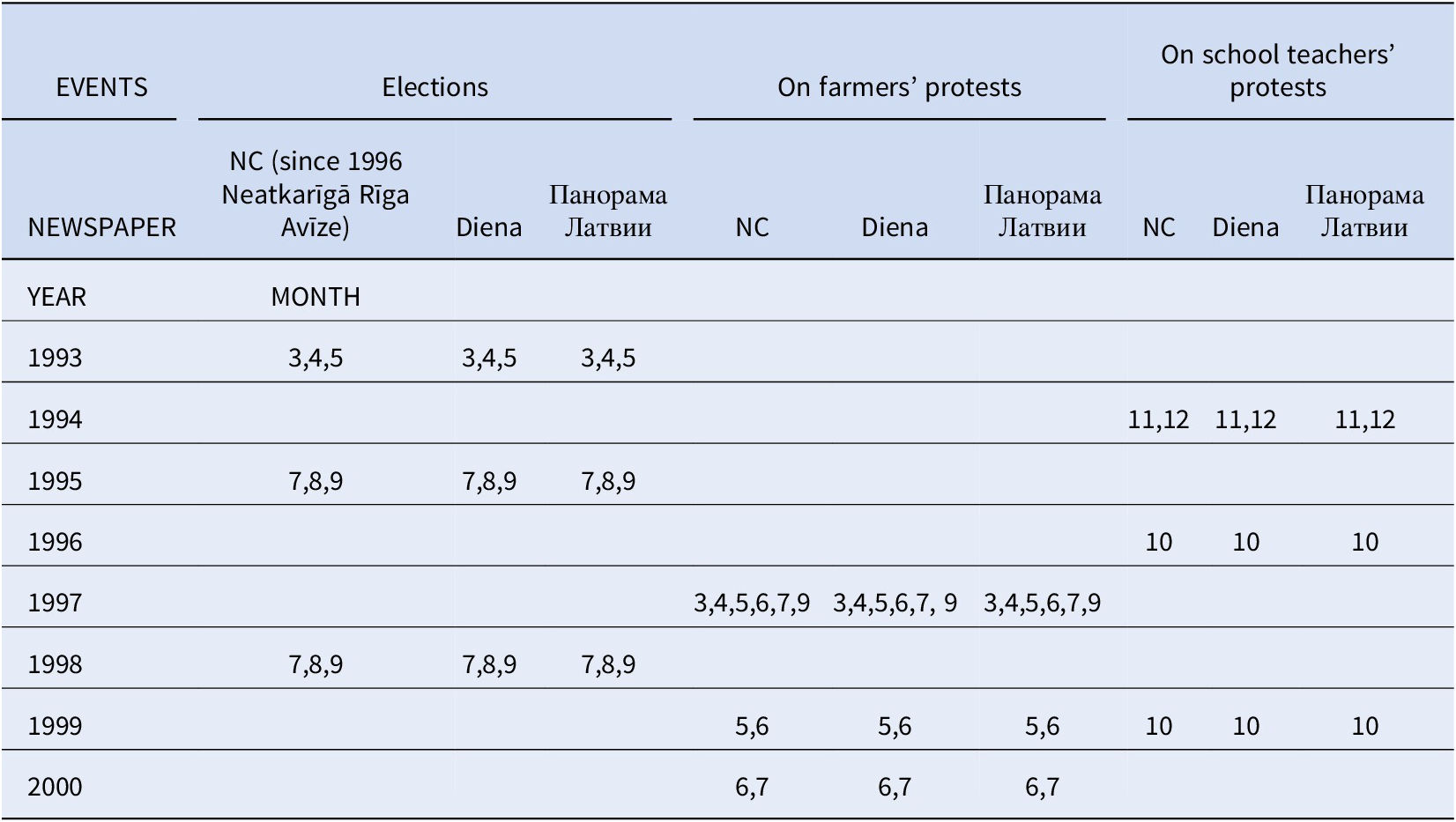

For the analysis of the civil discourse, I selected the two largest Latvian language newspapers (the Diena and Neatkarīgā Cīņa – so named until 1996, at which point it was renamed Neatkarīgā Rīta Avīze) and the largest Russian language newspaper (Панорама Латвии) in the 1990s.Footnote 1 I looked at the civil discourse in the first decade following the collapse of the Soviet Union because it was during this period that the state chose its course of development and established its new identity. This was also the period when the new democratic relationships between the state and its citizens were formed and framed. Since it was not possible to study every single article published in the post-Soviet period, I was influenced by Alexander and Smith’s (Reference Alexander and Smith1993) observation that in moments of “tension, unease, and crisis” or “liminality,” crucial meanings become visible (166). In terms of nationalism and national identity, Bonikowski similarly acknowledges that the “periods of heightened national self-awareness bring to the surface latent tensions that preexist and succeed them” (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2016, 429). Firstly, I decided to look at election periods in the 1990s, when future alternatives of the state were negotiated through public debates and revealed the deep meaning that the future held for the state-society bond. Specifically, I selected periods three months before the parliamentary elections in 1993, 1995, and 1998 (see Table 1, which shows the years and months selected for the analysis). For the election periods, I read interviews with politicians, columns, and editorial narratives, as well as articles that discussed the elections. Most of the articles were located on the first three pages of these daily newspapers. In the analysis, I focused on which patterns of the state-society relationship I observed in the discourse. Secondly, I turned my attention to specific protests in the 1990s. The protest events involving the people’s participation are significant moments because they are the time when views concerning certain aspects of the state practices are contested. I selected the largest and most repetitive protest events in the 1990s – the protests by schoolteachers and farmers (Table 1). Their repeated occurrence indicated the ongoing problematic state-society relationship and continued disagreement over some state policies. I selected the articles that present and describe these events, including interviews with politicians, involved actors, and columnists’ and editorial narratives. I paid attention not only to how these protest events unfolded but, same as to the election periods, also to how the civil discourse regarding the state-society relationship formed.Footnote 2 I take into account Illouz’s (Reference Illouz2011) criticism of the theory of social commitment, which invited us to analyze affective ties as related to specific cultural structures. To understand the state-society relationship, I paid attention to the symbolic structure of this discourse. This structure contains “the locus of meaning” (Kane Reference Kane2000, 314) and specifies what “good” and what “evil” is or what shall be prioritized (Alexander and Smith Reference Alexander and Smith1993; Alexander Reference Alexander2006). This specification is represented in “symbolic codes” or sets of binary opposites as structural elements of culture (Alexander and Smith Reference Alexander and Smith1993, 155; Alexander Reference Alexander2006). In the American civil discourse, the symbolic code of democratic/counter-democratic has been a powerful organizing referent of the civil sphere (ibid.). In post-Soviet Latvia and other Baltic countries, following other scholars, the code of West/East may be seen as a powerful referent for the actions of the political leadership (e.g., Mole Reference Mole2012; Eglitis Reference Eglitis2002). Cultural anthropologist Sahlins (Reference Sahlins1976) underlines “the gross distinction” between “development and underdevelopment” as being crucial in Western societies (211).Footnote 3

Table 1. Selected periods for the newspaper analysis.

Overall then, the analysis was not numerically driven, but as I “tracked [the] discourse” over the selected periods, I focused on underlying meanings and patterns (Altheide et al. Reference Altheide, Coyle, DeVriese, Schneider, Hesse-Biber and Leavy2008, 128, 130). As I was reading through the newspapers, I took notes on which discursive patterns and codes I saw in terms of the state-society relationship in the selected periods. Specific attention was paid to statements said by politicians and other public personalities who crucially influence the discourse due to their power (Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk1993). In the writing process, I went back and forth from my notes to the original newspaper articles. Selected empirical demonstrations contain examples that show discursive patterns of the state-society relationship in various situations over time.

In addition to the civil discourse, it is also essential to understand “the place of individuals in constructing national identity” (Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg2012, 134). In this case, I am relying on in-depth interviews with Latvian emigrants to the West who left after the Soviet regime collapse. In-depth interviewing does not aim for representative data but helps “to answer theoretically motivated questions” (Lamont and Swidler Reference Lamont and Swidler2014, 159). Studying the state-society relationships from the perspective of emigration is beneficial since emigration itself can be seen as a moment of “liminality,” which may illustrate existing “tensions” in the state-society relationship more strongly (Alexander and Smith Reference Alexander and Smith1993, 166). Since migrants have an opportunity to compare life abroad with life at home, the meanings related to the state-society bond are better exposed. I conducted and analyzed 59 in-depth interviews with Latvian emigrants to the USA, Ireland, and England collected between 2008 and 2014. I selected the respondents for the current study by using online social networking services such as Draugiem.lv and Facebook.com, contacts from the Latvian Associations and Latvian Language schools in receiving countries, and snowball sampling. There were 37 women and 22 men among the respondents. The respondents were between their late twenties to mid-sixties at the time of the interviews. People of various professional backgrounds (before the emigration) were included in the sample. Most of the interviews were in Latvian, with a few in Russian, and they were between 40 minutes to 3 hours long.

One of the rare studies on national pride that has an in-depth interview approach recognizes interviews as relevant to study “how ordinary citizens or individuals mediate national narratives and process complex emotional relationships with the nation” (Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg2012, 133). To ask people directly whether they feel proud of their state might be problematic since national pride is an analytical concept and may contain various meanings among individuals (Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg Reference Miller‐Idriss and Rothenberg2012). It may be more fruitful to see how national identity as a social bond and its relational facet – pride – gains its meaning and prominence in individuals’ lives through various daily experiences. My questionnaire covered such themes: respondents’ biography (where they were born, what they chose to study, what they did for a living, etc.), questions related to emigration and emigration context (how they decided to emigrate and what happened in Latvia before they emigrated, etc.), and experiences of living in Latvia and abroad, questions on return prospects and experience (if any). In the interviews, I intended to learn not only about my respondent’s emigration decision but also about their biography and views more broadly since I believed it could tell me more about their relationship with their state.

The way that narratives are told unleashes meanings, representations, and perceptions about the theme studied (Franzosi Reference Franzosi1998). My respondent narratives should not be seen as the “faithful representation of a past world” since, in the narrative analysis, the “truth” emerges “in the shifting connections [narrative accounts] forge among past, present and future” (Riessman Kohler Reference Riessman, Kelly, Horrocks, Milnes, Roberts and Robinson2005, 6). As I reread the data, I was particularly interested to see what emigrants narrate as meaningful regarding the state-society relationship, relationships among Latvian nationals, and relationships with the receiving states. These themes may help to understand the reasons for low national pride in Latvia since people act according to how they make sense of their lives and the broader milieu they live in.

Data Analysis

Discursive Level: Unrecognizing and Dividing Discourse

The civil discourse around elections in the 1990s was structured by the West (with its pair-opposite the East) code. It became the leading code in the sense that it organized under itself other such meaningful codes for Latvia’s post-Soviet identity as Right vs. Left, Liberal vs. Communist/Socialist, and Developed vs. Under-Developed (Ķešāne Reference Ķešāne2016). The Latvian state wanted to be recognized by the West, to belong to the West. In the sense of political leadership, this was possible by acclaiming right-wing (as opposed to the left wing) and (neo)liberal ideas since they may lead to the kind of development experienced by Western countries. The political elite referred to the need to do things “according to the European Standard” and praised the restructuring of state governance according to the advice of “foreign diplomats” (e.g., Jurkāns Reference Jurkāns1991, 1–2). This discourse structure cast the state-society relationships in a specific way: it revealed the political elite as not trusting national expertise but the Western one; within this discursive structure, the people appeared as not thinking and acting in ways that fit with the new neoliberal orientation.

The significance of the West code became apparent in “conversations” across and within newspapers (Ķešāne Reference Ķešāne2016). It was not common for the leading Latvian language newspaper Diena to publish articles that questioned Western institutions’ expertise, particularly their advice for liberalism and free market reforms. Such questioning was mostly discarded as threatening Latvia’s Western orientation. For example, Guntis Valujevs (Reference Valujevs1993a, Reference Valujevs1993b), who later became a Foreign Relations Department Head at the Latvian Bank and a Head of the Office of the Latvian Bank, published articles where he reproached politicians and journalists who asked questions about IMF practices in Latvia and who urged caution regarding how the European Union’s Maastricht Treaty might affect Latvia. He saw such questioning as impeding modern development and representing Russian or anti-Western views. In the newspaper Neatkarīgā Cīņa (from 1996 Neatkarīgā Rīta Avīze), Latvia’s Western orientation was supported when it was compatible with Latvia’s national identity, internal needs, development of the internal market, and societal wellbeing. Therefore, their journalists questioned the role of Western guidance more actively. For instance, when journalists of Neatkarīgā Cīņa questioned the Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Māris Gailis, and Finance Minister Elmārs Siliņš about the role of the IMF, WB, and European Communities in Latvia, we could learn these politicians had great confidence in these organizations. Māris Gailis, who would become a prime minister in the subsequent government, represented foreign experts as more knowledgeable than national ones in how to shape Latvia’s economy: “Foreign [Western] countries assist us with a particular purpose, and they give this assistance only in the way they consider necessary and good for us. Firstly, it is technical assistance that aims to restructure our economy swiftly and precisely […] This must help us get back on our feet faster” (Gailis Reference Gailis1993,1–2; author’s translation).

When journalists of Neatkarīgā Cīņa questioned Finance Minister Elmārs Siliņš about whether the Ministry of Finance had calculated how Latvia would repay all the loans the state of Latvia had received from international institutions, the Minister referred to foreign expertise rather than the expertise within his institution. According to him, the same institutions that gave these loans would also help to calculate how to repay them. He said that how to repay loans “is not a decision of the ministries, the government, and the parliament – we calculate it together with the International Monetary Fund” (Siliņš Reference Siliņš1993, 1–2). This firm confidence in Western expertise was related to the overall perception at that time that liberalism and a liberal economy were necessary orientations for Latvia to become part of the West (as opposed to the East or Soviet or Russian).

Within this discursive structure where the West code was central, Latvia’s national pride got externalized. The national pride was derived from Latvia’s recognition by the West. The logic was that if the West recognized Latvia, then the political elite and the people shall feel proud of it. In their comparative study on national pride, Fabrykant and Magun (Reference Fabrykant, Magun, Grimm, Huddy, Schmidt and Seethaler2016) similarly suggest that lower national pride in Eastern Europe could be explained by the fact that Eastern European populations “learned to consider more advanced Western countries as their reference group” (94). This kind of referencing and recognition seeking by the political elite might have further resonated in society in ways that were socio-emotionally damaging to the formation of secure state-society relationships. Instead of focusing on listening to and gaining recognition from the people, the state focused on building good relationships with Western institutions and experts and fulfilling their requirements for neoliberal reforms. As a result of this need for the West’s recognition, exaggeration became apparent where critical to democracy, “discourse of class, inequality and social justice” was “tainted” since it was associated with the East or Soviet (Eglitis and Lāce Reference Eglitis and Lāce2009, 331) – that is, the negative side of the West code.

Within this structure of the civil discourse, the Latvian people were represented as not knowledgeable, liberal, active, and business-oriented enough. In the election cycle of 1995, for example, amidst a crisis caused by the collapse of several banks that occurred due to insufficient regulation of the financial sector or too much neoliberalism, several articles in the newspaper Diena discussed the situation of liberalism in Latvia and argued that there had been too little of it (cf. Ķešāne and Weyher Reference Ķešāne and Weyher2021). This viewpoint was prevalent by the politicians of the ruling party Latvia’s Way (LC):

The biggest problem with this tendency [that people begin to look suspiciously at liberalism] in Latvia is individuals’ (ordinary people, civil servants, and politicians) inability, unwillingness, and lack of skill to carry out the true spirit of liberal reforms. […] Today it is said that liberalism has discredited itself in Latvia, but it is not so. If we begin to act in the inertia of socialism, without initiative and responsibility, then it is the fault of the people themselves rather than liberalism.

(Leiškalns Reference Leiškalns1995, 2)This framing – that not enough liberalism in Latvia was due to the Soviet characteristics of people, their lack of initiative, activity, and entrepreneurial skills – revealed that the state officials did not recognize and were not proud of its citizens as they were, expected them to change and even blamed them for the ineffectiveness of (neo)liberal reforms. Such discourse did not facilitate the formation of a secure social bond. Given that most of the population had lived and were raised under socialism, such talk by the politicians could also be seen as failing to recognize the Latvian people as it rendered them somewhat inadequate for Latvia’s future. Socioemotionally, it signaled that what was within the country was a source of shame while everything that came from abroad – and the West, specifically – was to be praised.

The civil discourse around the school teachers and farmers’ protests against neoliberal reforms in the 1990s was structured in a similar vein. Protesters’ claims were dismissed as inadequate since, according to the political leadership, they confronted Latvia’s belonging to the West and the development it entailed. This dismissal concerned all the schoolteachers’ strikes (in the autumn of 1994, 1996, and 1999, respectively) and farmers’ strikes (in the spring and autumn of 1997, in the spring of 1999, and in the summer of 2000, respectively) that I analyzed (cf. Ķešāne Reference Ķešāne2021). The schoolteachers protested against deteriorating working conditions and low wages. Farmers were concerned about the agricultural policy and issues such as the protection of the internal market, state subsidies, and taxation. The neoliberal economic policies that significantly reduced the state protection for agriculture and subjected it to global competition put Latvian farmers in a difficult situation.

The political elite tended to disregard the protesters’ demands. Instead of showing empathy with schoolteachers and farmers due to their impoverished situation, leading politicians used the tactic of shaming and pitted various groups against one another to possibly tame further protests. The protesters were advised to find individual solutions to their problems, work hard, and not expect support from the state. The protesters were also represented as citizens without the knowledge of broader development issues at stake. For example, in his response to the school teachers’ protesters in the fall of 1994, the leader of the leading political party Latvijas Ceļš Valdis Birkavs labeled protesters as “little men” not capable of understanding the overall socioeconomic and political situation, thus risking “to destroy the whole structure of the national budget” (cited in Miķelsone and Ločmele Reference Miķelsone and Ločmele1994, 1). Such lack of knowledge was also further related to the threat to Latvia’s national development and belonging to the West. During the farmers’ strike in 1999, the Minister of Finance Ivars Godmanis explicitly stated that the needy ministries, including the Ministry of Agriculture, would not get the funds claimed by the protesters as it would violate the austerity measures defined by Western donors. This reveals that the social bond between the political elite and the Western institutions was prioritized over the state-society bond.

The distancing rhetoric was supplemented by the pitting of various groups against one another. For example, in the announcement by the Cabinet of Ministers published in the Diena in response to schoolteachers’ protests, various groups, such as pensioners, doctors, and the needy, were pitted against one another. The announcement shamed schoolteachers, suggesting that their demands could be met at the expense of other groups (Valdības preses dienesta paziņojums 1994, 1). A similar discursive strategy was used by political leaders in response to farmers’ protests in the 1990s. The protests were depicted as destructive to Latvia’s development and endangering the wellbeing of other societal groups:

I would like to say something about the unrest among farmers. The most aggressive farmers say that they will sit on the railroad and block the trains. I must question whether these farmers have thought about those 18,000 railway employees and their families who will suffer the most from the railway stoppage. This stoppage will cost millions, and this might cause a salary decrease for railway employees and their layoffs. Somebody will suffer because of these damages, and it will not be the farmers but the railway employees. This is the destruction of the national economy.

(Krištopans Reference Krištopans1999, 10)From the perspective of social bond and commitment theories, the civil discourse was ineffective in fostering a secure social bond between the people and their state. Firstly, this was so since, in the post-Soviet era, the state elite focused on building trustful relationships with Western institutions, and the internal relationships were subordinated to this. Secondly, internally, the state-society relationships, as they appeared in the political leadership communication, tended to be based on denial rather than recognition and pride. People were cast as lacking vital characteristics of liberalism. Instead of empathy and understanding, there was the denial of people’s concerns and needs. Thirdly, as they appeared during protests, the state-society relationships did not shape a sense of joint task based on a fair exchange. The sense of shared responsibility that all people are together in this challenging transformation situation and what each party may do to improve the overall situation so that it is good for everyone was not there. Instead, the leading political elite pitted various groups against one another.

Individual Level: Insecure State-society Bond

Respondents’ narratives reflect the state-society bond as weak. My respondents perceived the state as not “salient” in their lives.The lack of the presence of the state in respondents’ lives was represented regarding economic development, the state’s policies and welfare practices, and how the state politicians and bureaucrats communicated with people.

According to respondents’ perceptions, the post-Soviet development meant the worsening of living conditions for many people. In this context, the state was seen as not leading development to benefit the people but rather to benefit investors and politicians. A construction manager whom I interviewed in 2014 (who left Latvia in 1998) explained that he could not live in Latvia anymore since the system was “unfair” there. He said the government officials should have thought about “how to ensure employment,” “for the good of people, foster their welfare but not think about their welfare disrespecting everything else.” Emigrants often pointed out the corrupted practices of the political elite. In their view, for example, the privatization process primarily benefited those in power. They represented politicians as concerned about their own wealth. Some respondents referred to the closure of the Soviet factories and the loss of employment. Those who took over the factories, whether by privatizing or buying them, were seen as “unfair” entrepreneurs, as “investors, shareholders, the ones able to subordinate.”

Others indicated that in the post-Soviet era the state could not create an environment where small entrepreneurs and farms could compete in the global market. For example, a woman who left for Ireland in 2003 when she was in her early forties expressed disappointment in the state in a context where the market practices and production standards introduced in independent Latvia proved an obstacle to the sustainability of her family vegetable business. Most of their clients – small shops – went bankrupt once the new shopping chains opened. There was nobody to whom they could supply the vegetables they grew. She referred to all the new production inspections and standards she had gone through in their attempt to remain their business as the “law of terror.” Such an experience of small farmers and gardeners in Latvia was also identified by anthropologist Aistara (cf. Reference Aistara2014). Consider also a Russian-speaking man in his mid-50s whom I interviewed in New York and who left Latvia in 2003 when his small business – a small livestock slaughterhouse or a meat processing business – ceased to operate:

—What happened in Latvia before you left?

—Nothing happened there in Latvia. Only the silent fading of the economy happened at that moment. There were huge transformations related to the accession to the EU. All our enterprises that somehow still managed to keep themselves above water could not compete. That they could not compete was related to the free trade with the EU, various norms, quotas, and production requirements […] in other words, the moral side of this process was terrible.

—Why?

—Because decisions were often made with the help of corruption. It seemed, for example, that some companies benefited from Euro-standards, managing the transition to Euro-standards. (Mid-50s, male, emigrated to the USA in 2003; author’s translation)

In respondents’ narratives, the post-Soviet development, including the entry into the EU, was represented as underdevelopment, “nothingness,” and “rack and ruin.” Latvian anthropologist Dzenovska (Reference Dzenovska2020) observes that rural Latvia people make sense of their lives through the notion of “emptiness.” In people’s perceptions, the emptiness refers not only to the high emigration and the demise of infrastructure and social services but relatedly to anxiety about the future. She explains that “emptiness in Latvia is symptomatic of post-Cold War spatiotemporal arrangements of power wherein capital and the state increasingly abandon people and places” (Dzenovska Reference Dzenovska2020, 10). For instance, a woman in her 60s who worked as an accountant in Latvia and subsequently as a florist in Ireland said,

It was when GodmanisFootnote 4 opened privatization, it was then that everything got looted. […] Everybody who was there at the feed bank [meaning the state] gorged themselves. And this is it. And after that, there was nothing in the countryside. (65, female, emigrated to Ireland in 1999; author’s translation)

Consider also a viewpoint of a man in his late 30s, whom I interviewed in the spring of 2014 and who came to an interview with his wife and daughter. When I asked him what happened in Latvia before his emigration, he said:

In Latvia, everything was fairly under decay. The salary of my mother and father we had to live on… nothing was really there. My mother was a school teacher and my dad was a chauffeur. (Emigrated to the USA in 2002)

More recent emigrants told similar stories. In 2010 on the outskirts of London, I interviewed a woman in her late 40s. By that time, she had been abroad for five months. She explained that her husband found it difficult to continue his forestry business in Latvia due to the overall decay of the countryside and the emptying of people from rural areas. She resented the state for its’ decaying of the countryside on purpose, so there are fewer people to pay pensions to. This sense of the state as “not thinking” about the people was common across interviews.

It was also a common perception that, due to the heavy taxation of employees, the state signaled that it only wanted money from the people. These perceptions of heavy taxation are consistent with the scholars who indicate that Latvia enforced extreme neoliberalism with a high flat tax rate on personal income (Eglitis and Lāce Reference Eglitis and Lāce2009; Stenning et al. Reference Stenning, Smith, Rochovská and Świątek2010, 52).

And then we had these terrible taxes, terrible. You earn 100 Lats, and 30 are taken away. I beg your pardon! (Late 40s, male, left for England in 2006; author’s translation)

There was a sense that the state needed people only as taxpayers. Between 2008 and 2011, the Latvian Parliament discussed a proposal that would require Latvian nationals abroad to pay the Latvian state the income tax difference from their earned income abroad. Some respondents’ perceived it as another injustice of the state toward the people:

They don’t have anything else to steal from, and now they say – please, come back. We want to steal from you, too [….] They only need taxpayers. (Mid-30s, male, left for the USA in 2002; author’s translation)

Emigrants’ experiences also reveal the state as fostering respondents’ exploitation and precariousness through social welfare programs. Several respondents explained that, in the situation of unemployment, the State Employment Agency offered them jobs that did not even meet the minimum wage standards (cf. Ķešāne and Weyher Reference Ķešāne and Weyher2021; Ķešāne Reference Ķešāne, Zepa and Kļave2011). Some respondents resentfully referred to the workfare program that paid 100 Lats per month (about 156 dollars) after the crisis of 2008 – an amount which in no sense met the basic needs.Footnote 5 These experiences are consistent with other scholars’ observations that the post-Soviet welfare policy facilitated precariousness (Eglitis and Lāce Reference Eglitis and Lāce2009).

The sense of neglect by the state also originated from the unpleasant face-to-face and discursive interactions with the state representatives. Some respondents felt humiliated at the state institutions, where instead of getting help, they often felt rejected. In the State Social Insurance Agency, the unemployed got their cases processed in a humiliating way (cf. Ķešāne and Weyher Reference Ķešāne and Weyher2021). The Officials at the State Revenue Service did not appreciate the fact that people paid taxes; they were suspicious and stern instead. For example, a manager in his early 40s whom I interviewed in Ireland in 2008 (and who arrived there in 2001) explained that he “can’t imagine a tax collector in Latvia, for example, standing up, shaking [his] hand and saying ‘thanks.’” In Ireland, he felt the tax collectors appreciated his contribution, while in Latvia there was a sense that he had “done something wrong.”

Several other respondents revealed they have often felt humiliated by the “elite talk” in the civil discourse. Consider a story from a woman in her late 40s who arrived from Latvia in the USA in 2005. Subsequently to working as an accountant in a restaurant, she opened her own business in Brooklyn, which was now highly valued in the surrounding community. She explained that she felt humiliated by the political leadership in Latvia because she was a single mother with four children. In the interview, she said she does not want to return to Latvia since she does not like “all the politics there.” Once I asked her what she meant by that, she explained that the government did not support her as a single mother with four children; the government “did not care that [her] husband did not pay alimony.” Then, when I asked further if she complained that these alimonies were not paid at some governmental institutions, she answered,

If I remember correctly, the wife of our President Ulmanis said about large families that these parents should have thought before they made these children. I was completely shocked by this. So, how can you go and ask for social benefits after this? If you have already been labeled as inferior, you understand. And I am sure this interview was there, and I was shocked by it. How can the first lady say something like this?

After feeling that the first lady had humiliated her for being a mother of four, she decided, due to her sense of pride, to avoid a situation where she would have to go and ask the government for help. This respondent explained proudly that she worked as an accountant for five companies and was paid enough to provide for her family while she was still living in Latvia.

A young woman with a degree in international politics who emigrated from Latvia in 2010 with her husband and a baby daughter showed great disappointment in the Latvian state. I asked her why we Latvians do not do something about this disappointment. She answered that she has “no motivation” and gave an example about the news article that uncovered that “deputies think that the ticket in public transport costs 20 cents [in the capital].” She said, “how can we believe in such politicians that for a long time there is already a different price.” With her meaning making, she symbolically indicated the great distance the political elite had from the people. The state is not only a set of institutions but also a “talking” state (Epstein Reference Epstein2010, 341). This means the state communicates and interacts with the people through its representatives, such as politicians, bureaucrats, and so on. Such unrecognizing and inconsiderate practices of the state representatives did not foster the state-society connection but promoted individualization instead. It compelled respondents to choose strategies to avoid their state and the humiliation it projected on them.

Overall, respondents’ perceptions and meaning-making indicate weak state-society bonding where humiliation, resentment, and anger prevail. Across interviews, no confidence in their state was apparent. It is difficult to imagine that, in this situation, informants may feel pride in the state’s political and economic achievement. A quantitative study that accounts for low national pride in the Czech Republic similarly explains that confidence in the government and democratic environment is crucial for national pride to flourish (Vlachová Reference Vlachová2019). In the 1990s, there was low trust in the parliament and political parties in Latvia (Zepa Reference Zepa, Loftsson and Choe2001). According to Eurobarometer data, in the last two decades, 70% and more of the population do not trust parliament, government, or political parties. Many respondents, however, have found their receiving states as present or salient in their lives and now desire that the Latvian state would become like their receiving states. In those relationships, instrumental ties between emigrants and receiving states allowed positive affective ties to be formed. This was so because these instrumental relationships made my respondents feel good about themselves, their work and contribution to society, and they felt recognized (cf. Ķešāne Reference Ķešāne2019; Ķešāne and Weyher Reference Ķešāne and Weyher2021) and thus wanted to remain in emigration.

The narratives of emigrants further indicate that the practices of the state not only adversely affected the state-society relationships but also alienated people from one another through the mechanism of “displaced aggression.” The socio-psychological theory of “displaced aggression” explains that “people react to a provocation from someone with higher status by redirecting their aggression onto someone of lower status” (Wilkinson and Pickett Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2010, 166). For example, someone humiliated by his employer is aggressive with his family members later (166). For this study, the humiliation that people have experienced in their relationships with the state representatives may have resonated further in societal relationships.

Most of the interviewed emigrants mentioned impoliteness and daily aggression as a seemingly conventional social phenomenon in Latvia. Anger and aggression were seen as present not only in communication with the state representatives but also in communication with other Latvian colleagues at home and in emigration. Respondents described how, when visiting their home country, they could not stay there for more than two weeks since they felt a sense of “nausea” due to the impoliteness and daily aggression they experienced there. Let us see the following excerpt as an example:

After a longer time, I was in Latvia. I went into a supermarket, I went through it, I felt bad, simply all that stress, that negative energy everybody emanated. I felt nauseous. I went out, and I did not understand what I was doing there. I don’t want to be in such a country. When those things change, when there is the benevolence we have here [in Ireland] …. Ok, it changes but very slowly. (42, male, emigrated to Ireland in 2000; author’s translation)

Other respondents described relationships among Latvian nationals as discourteous by using phrases such as “a Latvian will eat another Latvian” and “where there are two Latvians, there are three political parties.” Although some Latvians cherished Latvian culture abroad through Latvian folk dancing and choir singing, thus keeping in close contact and friendship with other Latvians, I often heard respondents preferring to make friends with people of other nationalities who are more courteous and supportive. OECD reports that Latvian students have the highest exposure to bullying compared to other OECD countries (2017, Figure III.8.2). This might indicate socialization where impoliteness and aggression have become a daily norm. The rejecting and humiliating post-Soviet civil discourse discussed in the previous section might have been one such socialization agent. Thus, it is no wonder that a respondent emphasized politeness and respectful relationships as meaningful to her wellbeing and as the criterion of “civilization” she did not find in Latvia:

The first and the major motive [for emigration] was money, but then I saw this other world, how people actually should live, at what level and quality towns should be, what the quality of services should be, and this kindness, this mutual politeness in relationships… I understood that in Latvia, we are very far from all this, and that life is not so long for me to wait until civilization arrives in Latvia. (34, female, emigrated to Ireland in 2001; author’s translation)

More respectful relationships are essential for social trust and thus a sense of community to form. In explaining low national pride in the Czech Republic, Vlachová (Reference Vlachová2019) finds that social trust is necessary for national pride. From an affective perspective, relationships that are based on aggression and anger impede the formation of social trust.

Müller-Peters (Reference Müller-Peters1998) argues that “national pride in the global sense is linked to the very dimension of national identity which includes downgrading of outgroups” (706). However, we see from the civil discourse and people’s experiences and perceptions that in post-Soviet Latvia, downgrading also happened within the group. As it appeared in its communication in the mass media, the political elite did not recognize the national expertise and the people and pitted various groups against one another. In turn, the people developed resentment and anger toward the state and impoliteness toward each other. Not only does this weaken the national social bond and commitment, but it also makes the members of that group prone to other groupings that are more recognizing and able to boost one’s self-esteem, be it other nations (Ķešāne and Weyher Reference Ķešāne and Weyher2021), anti-vaxxers, or various other communities.

Conclusion

In this article, I explain low national pride in political and economic achievement in post-Soviet neoliberal Latvia. I do this from the broader framework of national identity since, following social bond and commitment theories, national pride reflects the character of national identity. Namely, national identity is a social bond, and it is positively strong in situations where the parties involved are mutually acknowledging and listening to each other. Given that other studies have mainly analyzed national pride from the perspective of how people feel (or do not feel) pride in various aspects of their country, following these theories, it is essential to analyze how the state relates to its people. If the state fosters a sense of salience, collective efficacy, and the accompanying sense of shared responsibility among people, they feel a positive attachment to the state and will feel proud of its achievements (cf. Lawler, Thye, and Yoon Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009).

Empirically, I demonstrate this through the case of Latvia. I explain that low national pride in Latvia resulted from alienating relationships between the state and its people in the context of post-Soviet neoliberalization. Firstly, the analysis of the civil discourse reveals that in the years following the regained independence, the state elite focused on gaining trust from and building relationships with the Western institutions by fulfilling their requirements for the neoliberal reforms. The internal relationships were subordinated to this. Such an arrangement was a result of broader geopolitical and symbolic processes where the Latvian state sought to belong to the West. Secondly, as they appeared in the civil discourse, the state-society relationships tended to be based on denial rather than recognition and pride. In the context where it was essential to foster Latvia’s belonging to the West, seen as representing (neo)liberal values, people were cast as lacking vital characteristics to carry the spirit of liberalism. Instead of empathy and understanding, there was also a denial of people’s concerns and needs. Talk of the leading political elite revealed that the political elite tended to disregard societal claims that conflicted with Latvia’s Western orientation. Emigrant in-depth interview analysis supports this observation since respondents’ experiences also reveal disturbing communication with the state representatives. Emigrants often experienced and perceived their state as rejecting and ignorant and unwilling to recognize their needs. Thirdly, the state-society relationships, as they appeared during the school teacher and farmers protests in the 1990s, did not shape a sense of joint task based on a fair exchange. It seems the state in the new neoliberal context was unable to serve as “a source of collective efficacy”; in other words, it was not effective in fostering people’s ability to cooperate and work for the common good (Lawler, Thye, and Yoon Reference Lawler, Thye and Yoon2009, 153). With its individualizing and dividing rhetoric, the political leadership tended to pit various groups against one another, thus generating a sense of anger, which further resonated within societal relationships as a lack of social trust. Analysis of emigrants’ narratives suggests that mutual relationships among people were suspicious and stern rather than facilitating a sense of solidarity.

It is argued that “national pride involves both admiration and stake holding – the feeling that one has some kind of share in the achievement or an admirable quality” (Evans and Kelley Reference Evans and Kelley2002, 303). The civil discourse – developed in response to Westernization and neoliberalization –rejected people as they were and thus did not create a sense that people’s claims matter or are worthy in the new shaping of Latvia. Such a situation raises the question of how people can form a healthy social bond as the basis of national belonging if they are routinely rejected and even belittled. Rejection and no recognition impede the sense of dignity, bonding, and belonging. “Dignity is a form of pride, a feeling that others respect you, but it also includes the feelings that others have toward you” (Jasper Reference Jasper2018, 139). In this instance, the state-society ties, following Scheff (Reference Scheff1994), facilitated engulfment, meaning that people could not live their lives with dignity. Their identities were not recognized as worthy (for instance, the identity of a schoolteacher, a farmer, or a mother of many, etc.). However, the state-society bond also became isolating in the sense that people stopped counting on their state and each other in their lives. Scheff (Reference Scheff1994, 2, 17, 58) would call it a “bimodal alienation,” a situation that impedes secure social bonding. This is within this context of “bimodal alienation” that we interpret low national pride in Latvia’s economic and political attainment: people perceived that their concerns about their country’s course of development do not matter, and how the country develops is not in their interests but in the interests of other players, such as various Western institutions, businesses, or the political elite itself. It is very likely people did not feel pride in the political and economic achievements because they did not feel they could contribute to it and could not always see how what happened in terms of national development benefited them.

Suppose we see national identity as a form of social bond that is mediated by the emotions of pride and shame or mutual recognition. In that case, this study shows that this bond in Latvia has been fragile as it has been predominated by a lack of recognition, humiliation, and shame rather than pride. Other data and research also indicate this fragility as among those who remain in Latvia; there has been a low willingness to take arms and fight for Latvia in a situation of need (cf. Ozoliņa Reference Ozoliņa2019). This article indicates that interactions between the state and its people have not generated positive affective state-society ties as a basis upon which national social commitment or loyalty could flourish. In a situation of the currently unjustifiable Russian invasion of Ukraine, this explanation of low national pride in Latvia can serve to strengthen social bonds, the sense of community, and commitment within Latvia, thus helping boost national pride and belonging. This is particularly pertinent since the recent surveys show that despite the sense that the Russian invasion of Ukraine might have improved the willingness to defend Latvia, the surveys show that this will has not increased (RSU 2022).

Hjerm (Reference Hjerm2003) distinguishes between political and cultural national pride. This study primarily addresses the former concept. Empirical studies show Latvians are prouder about Latvia’s cultural achievements than political and economic ones (Fabrykant Reference Fabrykant2018). Like other Latvian migration scholars (Kaprāns Reference Kaprāns and Mieriņa2015), I too observed among my respondents that people began to cherish their language, music, and dance more in emigration. Does this finding suggest that cultural pride could help strengthening national identity in the context where political and economic pride is too weak to do it? Fabrykant (Reference Fabrykant2018) finds that in the Baltic countries, cultural pride coexists with “the relative less importance attributed to cultural national identity criteria” (23). The state’s attempts to form a national bond through the cultural industry in a situation where political and socioeconomic distancing is practiced may be ineffective. If the Latvian state attempts to create a sense of national bonding only through cultural products but not through mutually recognizing and caring interactions with its people, it will create a national identity as a pseudo-bond that will be fragile.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. L. Frank Weyher for introducing her to social bond and commitment theories and Liene Ozoliņa and Maija Spuriņa for their comments and advice in the process of writing. I thank the journal editors and two anonymous reviewers for their guidance, critique, and advice. It was greatly appreciated and very helpful. I sincerely thank my informants for sharing their stories with me.

Disclosure

None.

Financial support

Various stages of this research were supported by the German Academic Exchange Service; the Latvian State Research Program “National Identity”; the Fulbright program; and the Jānis Grundmanis Fellowship.