Introduction

Sub-national governments interact often with foreign entities (Cornago Reference Cornago2010). This is the case in the former Soviet Union (FSU) as well: mayors like Yuri Luzhkov have enacted wide-ranging projects for Russian speakers living abroad (Saari Reference Saari2014), while Tbilisi asked for direct assistance from Bristol after Georgia’s civil war in the 1990s (Couperus and Vrhoci Reference Couperus, Vrhoci, Braat and Corduwened2020). Scholarship on this topic in the region is in short supply, however, both in terms of empirical findings and theoretical reflections. What is the nature of the diplomatic affairs of mayors in the FSU? And what impact do they have on the central government’s foreign policy?

This article makes two arguments that seek to answer these questions. First, mayors in the FSU are autonomous foreign policy actors that deserve attention in both area studies and foreign policy analysis scholarship. Such officials have their own foreign policy preferences, which are derived from their political beliefs on matters like national or ethnic identity or EU- or Russia-driven integration processes. Mayors institutionalize these preferences by using the visibility of the office of mayor in national politics to engage in diplomatic affairs. Second, a mayor’s foreign policy can have several consequences for the national foreign policy-making process: actions and inactions can either undermine or support the foreign policy goals of, or actions conducted by, central authorities, depending on the degree to which local and national foreign policy preferences clash.

These claims are corroborated with evidence from a case study of the foreign policy of Chișinău mayor Dorin Chirtoacă from 2007–2017. Chirtoacă entered Moldovan politics in the mid-2000s and won his first term in office in 2007, becoming one of the youngest mayors of a major city in the post-Soviet world (British Broadcasting Corporation 2007a). He was suspended from office in mid-2017 because of an ongoing investigation into corruption allegations and resigned at the beginning of 2018 (RISE Moldova 2020). The case of Chișinău was selected because an investigation of the domestic and foreign policy of a post-Soviet city heretofore ignored in scholarship is an inherently valuable exercise for area studies scholarship. It is also a theory-building inductive endeavor that will, one hopes, lead to broader insights and replication across the post-Soviet area. Such an inductive effort is necessary in light of the absence of a clear set of hypotheses in the existing literature on post-Soviet foreign policy related to whether mayors are foreign policy actors, what their preferences are, and how those endeavors affect the central government’s goals. Finally, the Republic of Moldova is highly polarized over foreign policy (see, for example, King Reference King2003), making it an easy case for the demonstration of the points above. Choices of geopolitical and identity matters are front-and-center in Moldovan politics (Călugăreanu Reference Călugăreanu2016), including in local political races, and mayors in the country often campaign on their positions on these matters as much as they do on more pedestrian administrative topics.

For this purpose, I developed a dataset of Chirtoacă’s visits abroad, meetings with ambassadors at city hall, and meetings with other types of delegations at city hall (including officials representing local, national, and international institutions and individuals not affiliated with a government or an international organization) as the main measures of the mayor’s diplomatic affairs. The data was collected from the mayoral website, which is the most comprehensive account of daily activities.Footnote 2 Beyond the general geographic patterns identified in the dataset, I also analyzed the content of the mayor’s rhetoric during all of these diplomatic encounters, with an eye to learning how Chirtoacă framed the goals of his diplomatic endeavors.

Throughout his tenure in office, Chirtoacă pursued a consistent foreign policy based on three major pillars. First, the mayor developed close ties with local and national Romanian decision-makers, including via the signature of two major sister-city agreements. Second, he consolidated Chișinău’s connections to the European Union, including by claiming leadership in several European-level institutions and receiving funding for the city from organizations like the European Investment Bank (EIB). Finally, the mayor minimized contacts with the post-Soviet space, especially with Russia. These foreign policy actions largely reflected Chirtoacă’s political views, which hinge on his beliefs that Moldovans are Europeans and deserve to be a part of the EU, that the majority population in Moldova is ethnically Romanian – and, consequently, that Moldova should seek forms of reunification with the neighboring country – and that historical Russian and Soviet control and influence in Moldova have constituted occupation and the denationalization of the majority population.

Chirtoacă’s diplomatic activities had consequences for the center’s ability to enact its foreign policy priorities. When Chirtoacă and central authorities agreed on these priorities, his actions and inactions supported the center’s policies by further institutionalizing them at the local level. This was the case with Moldova’s and Chișinău’s foreign policy toward the European Union (throughout Chirtoacă’s entire time in office), as well as Romania and Russia after 2009. In contrast, when central authorities and the mayor disagreed on those priorities, Chirtoacă undermined the center’s pursuit of foreign policy. These conflicts occurred primarily in 2007–2009, when Chirtoacă undermined the ability of the central government to punish Romania for perceived attacks on Moldova’s sovereignty by continuing to hold high-level meetings with Romanian officials. By minimizing ties with Russian officials, Chirtoacă also obstructed the central government’s stated policy of developing bilateral relations, especially at the local level.

This finding outlines a major insight on city diplomacy in the former Soviet Union: foreign policy-making in this region cannot be understood properly unless mayors are taken into consideration as potential participants in diplomatic affairs and as agents that either run against or with the grain of national foreign policy. Mayors are not always going to be salient, but their involvement in and impact on foreign policy is an empirical question that requires further investigation in each specific case. Such actors are important: they have access to government institutions at the local level that provide an existing infrastructure with which to establish foreign contacts. From this perspective, mayors have more institutional tools for the conduct of autonomous foreign policy than legislators and opposition leaders.

The article begins with a short summary of the literature on post-Soviet foreign policy and city diplomacy, which is sparse on the role of mayors. A description of major debates in Moldovan foreign policy and Chirtoacă’s beliefs follows. Finally, the article examines the nature of the three main pillars of Chirtoacă’s foreign policy and their consequences for the central government’s foreign policy. The article concludes with reflections on how the article’s approach can be expanded to other post-Soviet cities where extensive data is available, and beyond.

The study of the foreign policy of post-Soviet states has developed in multiple directions since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The article touches on two major themes and one limitation that are of relevance for city diplomacy. First, ethnic identity and nationalism continue to have an impact on how post-Soviet states interact with the world and inform both behavior and rhetoric (King and Melvin Reference King and Melvin2000). Russia’s relationship with (and construction of) its diaspora is noticeable in this strand of scholarship (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2015), but the phenomenon is prominent in other post-Soviet states (D’Anieri Reference D’Anieri2012; Cavoukian Reference Cavoukian2013; Ambrosio and Lange Reference Ambrosio and Lange2014), where the construction of a national identity and transnational ethnic networks continue to influence foreign policy choices. Second, Moscow’s policies to fashion and control integration processes after the collapse of the USSR have garnered significant scrutiny (Kubicek Reference Kubicek2009) as rival integration processes in areas like the European Union’s neighborhood have opened possibilities for alternatives (Korosteleva Reference Korosteleva2016) and have elicited reactions, often hostile ones, from Moscow (Konopelko Reference Konopelko2018).

In coverage of these topics – as well as many others – post-Soviet foreign policy scholarship remains mostly state-centric, in the sense that authors continue to focus primarily on the decisions and behaviors of central decision-makers and to examine the domestic and external variables that affect their ability to engage in diplomatic affairs. This focus on states as actors is not necessarily a flaw: it reflects the overwhelming influence of central decision-makers on foreign policy processes in the post-Soviet area. It does provide a limited picture of the diplomatic landscape in the former Soviet Union. Some exceptions to this rule have begun to shed more light on the variety of actors that engage in foreign policy while speaking to the aforementioned themes.

De facto and separatist states have received a lot of attention (Lynch Reference Lynch2004) when it comes to support from patron-states like Russia (O’Loughlin et al. Reference O’Loughlin, Toal and Kolosov2017; Kosienkowski Reference Kosienkowski2020), identity construction (Littlefield Reference Littlefield2009), and their impact on integration processes (Tudoroiu Reference Tudoroiu2012). The study of the foreign policy of such entities sheds light on the manner in which elites not affiliated with the central government assert their agency (Berg and Vits Reference Berg and Vits2018; Beachain Reference Beachain2019), including the use of formal and informal networks to bypass central authorities that claim sovereignty over the territory they control (Frear Reference Frear2014). Other actors like legislatures (Petrova Reference Petrova, Raube, Muftuler-Bac and Wouters2019) and the Orthodox Church (Lomagin Reference Lomagin2012) have also received some degree of attention, especially their influence on the executive’s ability to make and implement foreign policy and occasional conflicts with central authorities.

Another exception to the dominant state-centrism in scholarship is the study of the foreign activities of constituent units (also known as paradiplomacy; see Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov2015 and Nganje Reference Nganje2014 for detailed reviews of the literature). The foreign activities of entities like Tatarstan indicate that diplomatic actions have been frequent when it comes to economic development or a desire to project a separate regional identity (Sharafutdinova Reference Sharafutdinova2003; Albina Reference Albina2010; Shklyar Reference Shklyar, Dwan and Pavliuk2000; Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov2015). Regional elites have also antagonized central authorities at times on account of disagreements about major foreign policy issues like the South Kuril Islands/Northern Territories (Williams Reference Williams2006) or have bypassed central authorities entirely in efforts to establish direct ties with foreign entities (Demchuk Reference Demchuk, Kivinen and Pynnoniemi2002). This strand of literature reveals, then, that sub-national actors can have their own preferences, can get involved in foreign policy processes in the post-Soviet space, and can antagonize central authorities. It also shows that the study of the diplomatic landscape in this area can benefit from broadening the agents taken into consideration.

The limited scholarship that does surface on city diplomacyFootnote 3 in the post-Soviet era reveals that cities engage in a variety of actions, including participation in regional networks (Kusku-Sonmez Reference Kusku-Sonmez2014), the creation of city networks (Burksiene et al. Reference Burksiene, Dvorak, Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, Amiri and Sevin2020), city twinning and cooperation that vary in terms of depth and content (Joenniemi and Sergunin Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2012), the opening of offices abroad (Burksiene et al. Reference Burksiene, Dvorak, Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, Amiri and Sevin2020), and the organization of various international events (ibid.). Russian and, more recently, Baltic cases tend to prevail, with scarce information on the remaining post-Soviet states.Footnote 4

Recent evidence shows that mayoral diplomatic activities can be substantial: in a study of four Baltic cities, Burksiene et al. (Reference Burksiene, Dvorak, Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, Amiri and Sevin2020) find that “all mayors have meetings with ambassadors from both EU and non-EU countries, as well as leaders of global organizations, where they discuss global as well as state-level problems” (323). Unsurprisingly, the activities of Russian mayors tend to get the bulk of the attention, with Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov garnering the lion’s share (Alexandrov Reference Alexandrov2001; Kolossov et al. Reference Kolossov, Vendina and O’Loughlin2002; see also Golubchikov Reference Golubchikov2010 on Saint Petersburg).

These diplomatic activities are set in the context of broad global processes like European integration (Joenniemi and Sergunin Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2012; see also Favell Reference Favell2011 on the Eurocities program) and are affected by the relationship between central governments in which the cities are located (Joenniemi and Sergunin Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2012, 28, 30; Stoklosa Reference Stoklosa2017), NGO activism (Burksiene et al. Reference Burksiene, Dvorak, Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, Amiri and Sevin2020, 326) and prior historical ties (ibid.), for instance. The relationship of these cities with the center is notable in light of the USSR’s use of city twinning to pursue central foreign policy goals (Laguerre Reference Laguerre2019; Scarboro Reference Scarboro2007), which has left behind an infrastructure of city diplomacy that continues to be used by mayors.

The relative absence of scholarship is surprising being that the preliminary findings speak to the aforementioned themes covered by post-Soviet foreign policy scholars. First, city diplomacy – particularly in non-Russian cities – is embedded in the frequent back-and-forth between East and West integration. Burksiene et al. (Reference Burksiene, Dvorak, Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, Amiri and Sevin2020) analyze the city diplomacy of four Baltic states active in the Eurocities program, which occasionally engage in actions that antagonize central authorities pursuing a more pragmatic diplomatic orientation toward Russia. In links between Narva (Estonia) and Ivangorod (Russia), Joenniemi and Sergunin (Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2012) find both tensions and pathways to conciliation that emerge as these cities navigate EU-Russian exchanges (see also Stoklosa Reference Stoklosa2017). Second, city diplomacy often intermingles with ethnic identity and nationalism in terms of the motivations of local actors and the depth of dealings pursued across the world. Alexandrov (Reference Alexandrov2001, 27) reveals that Yuri Luzhkov’s foreign policy in the 1990s, which included support for Russian speakers, was occasionally at odds with federal policy. Local and national identity issues in Estonia, Latvia, and Russia often serve as an impediment to stronger connections between border cities (Joenniemi and Sergunin Reference Joenniemi and Sergunin2012, 30, 39).

Bearing in mind these gaps in the literature, a deductive approach based on hypotheses culled from the existing literature is unlikely to be fruitful in the absence of systematic theoretical efforts. Instead, this article proposes an inductive approach that analyzes the extent of a post-Soviet city’s diplomatic affairs, its content, the political beliefs of the mayor, the relationship between the local and central levels of decision-making, and consequences for national-level foreign policy. The case study below will touch on mayoral beliefs, referring to the articulation of ethnic and national identity, as well as opinions on EU or Russian integration processes, and how such positions influence the actual conduct of city diplomacy.

Moldovan Foreign Policy and Dorin Chirtoacă’s Beliefs

Chirtoacă’s foreign policy is impossible to understand without first looking at national-level trends in Moldovan foreign policy during the time he was in office and at both the mayor’s and his party’s positions on major diplomatic directions. Mayor Chirtoacă’s behavior was embedded in national politics because Chișinău is the largest city in the country and the site for most of the country’s political and diplomatic life. Chirtoacă’s party during this period – the Liberal Party (PL) – sought to secure more power at the central level, and the mayor’s seat was a major institution that helped the party illustrate what a PL foreign policy may look like. Before and during his time in office, Chirtoacă (and PL) consistently expressed a set of beliefs about major issues in Moldovan politics: the ethnicity of the majority population, Moldova’s national and European identity, and the country’s historical and current relationship with Russia and the former Soviet Union.

Most of the territory covered by the Republic of Moldova today was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812. The region at the time was populated by primarily non-Russian speakers who did not have a particularly strong national identity but were part of a loose cultural space of speakers of unstandardized Romanian with regional identities (Van Meurs Reference Van Meurs1998; King Reference King2000). Deprived of contact with the main ethnic and national identity-construction efforts in Romania proper for most of the 19th century (King Reference King2003), the population’s identity has since been incorporated into several nation-building projects and has, as a result, been contested: Romanian elites have claimed the territory’s Romanian identity, while proponents of a separate Moldovan identity have claimed somewhat overlapping but different ethnic origins. In the latter case, Moldovan identity has been tied to conceptions of statehood separate from the Romanian state (Van Meurs Reference Van Meurs1998), bolstered, according to its proponents, by Russia and the Soviet Union. Supporters of a separate Moldovan ethnicity are emphatic that the country’s language is called Moldovan and is, despite similarities to Romanian, different (see Cărăuș Reference Cărăuș2001, 24–26, 29–30; Ciscel Reference Ciscel2006).

In the 20th century, most of the Republic of Moldova was subsequently part of Romania between the two world wars and became a part of Bucharest’s identity-building projects that sought to create a Romanian nation (Cash Reference Cash2007, 592). After World War II, however, Moldova became one of the 15 Soviet republics, with the population subjected to Sovietization and efforts to bolster narratives of a separate Moldovan ethnicity to fight Romania’s claims of cultural and ethnic unity (Anderson Reference Anderson2005, 84). These historical experiences further developed narratives that, on the one hand, the majority ethnicity is Romanian and that the Russian and Soviet periods constituted occupation and denationalization. In contrast, to proponents of a separate Moldovan identity, it was the Romanian period that constituted occupation, with Russian and Soviet periods mostly providing an opportunity for the Moldovan identity to survive, flourish, and resist Romanian attempts at Romanianization (Cărăuș Reference Cărăuș2001, 24–27).

Dorin Chirtoacă’s political beliefs fall clearly in the pro-Romanian camp. First, the politician has argued that the majority population in the country is Romanian; he self-identifies as such, as well. In 2010, for instance, Chirtoacă told Radio Romania Actualități that “about 15-20 percent of the population of the Republic of Moldova realizes very well that, from an ethnic standpoint, we are talking about the notion of Romanian. [ … ] The others, subjected to permanent intoxication from the Soviet period, believe that to be Moldovan means to be part of a nation separate from the Romanian nation” (Radio Romania Actualități 2010).Footnote 5 In 2008, Chirtoacă explained that he was “born in a family of fighters for the national cause, where only the Latin script was used for writing, letters that were signed clearly were sent to Radio Free Europe, and all national Romanian holidays were observed” (Formula AS 2008).

In 2014, the mayor noted that

we have two more things to resolve in this regard [Moldova’s ties with Romania]: the identity problem and the problem of national unity. The identity problem, in the sense of recognizing that Moldovans, Transylvanians, and Oltenians are Romanian, and that it no longer makes sense for someone to try to divide them up; regular people will slowly understand this, I am certain of it. With respect to the problem of national unity; that will be resolved gradually, along with integration in the European Union via the majority will of the people on both shores of the Prut. (Gazeta Românească 2014)

These views are accompanied by a policy preference for closer ties with Romania, including potential unification: “Even though we think about Moldova’s return to the motherland, that will happen, we hope, within the European Union, not only to the benefit of Romanians, but to the benefit of all of the republic’s citizens” (Formula AS 2008). To Chirtoacă, Moldova’s Romanian identity dovetails with its European identity. The mayor emphasized in 2010 that Moldovans “have every right to be European citizens, just like Romanian citizens are citizens of Europe” (HotNews 2010) and, in a 2013 speech, argued that the Eastern Partnership “is for us a chance to return to the great European family, where our roots are” (Partidul Liberal, July 26, 2013).

Finally, Chirtoacă’s beliefs in Romanian and European identity are accompanied by narratives of Russian and Soviet occupation and denationalization. In a 2008 interview, Chirtoacă said that he became involved in politics “to honor the memory of my grandparents, who were deported to Siberia. Even my uncle, Gheorghe Ghimpu, spent six years in the GULAG in the 1970s for his anti-Communist attitude” (Formula AS 2008). In 2006, Chirtoacă said that his party would form an alliance with other liberal groups only if they have members that “did not work in Soviet occupation structures” (Basa-Press, October 24, 2006). That same year, Chirtoacă noted that Russia constituted a threat to Moldova’s sovereignty and that “we must not consider ourselves inferior to Russia. As a state, we have the same rights” (Basa-Press, March 29, 2006). In addition, the politician said in 2007 that during a visit to Germany he learned that “the truth about the Communist past can and must be revealed” and promised that his party would initiate a campaign to teach young people about “the totalitarian Communist past and its remnants in the present” (Basa-Press, March 19, 2007). These views were accompanied by a belief in the need for a “pragmatic relationship based on economic and trade ties” (Adevarul 2009) and “respect and mutual advantage” with Russia (Ziarul de Gardă 2010). Such beliefs have been accompanied by statements about reducing dependence on Russia (especially when it comes to the import of gas) (HotNews 2010). Chirtoacă said in 2014, for example, that “the Liberal Party wants for Moldova to tear itself away from Russia and join the European Union” (Gazeta Româneasca 2014), adding that if Moldovans do not support a “European and democratic government, we risk being very disappointed and a return toward Russia, which is not desirable.”

Chirtoacă brought these beliefs with him to city hall and occasionally came into conflict with central authorities over them. From 2007, when Chirtoacă took office, until 2009, the country’s branches of government were dominated by the Party of Communists (PCRM), which had taken power in 2001. Initially, the party portrayed itself as a hardline Leninist group (March 2005) that shared the Kremlin’s Soviet-era historical and identity narratives, the rejection of the Romanian identity of the majority population in the country, the largely positive and nostalgic description of the Soviet experiment, and the importance of preserving a strategic relationship with Moscow after the collapse of the USSR (March 2007). Starting in 2003, however, conflicts over the resolution of the Transnistrian conflictFootnote 6 and PCRM’s increasing acceptance of European Union integration as a major foreign policy goal led to tensions with Moscow, which was followed by the Kremlin’s imposition of punitive measures in areas like trade. PCRM never renounced its strategic relationship with Russia and, despite tensions, remained committed to this goal. In 2006, President Voronin met with his Russian counterpart, after which the relationship improved somewhat (Vrabie Reference Vrabie, Șarov and Ojog2009, 80; see also Devyatkov Reference Devyatkov, Kosienkowski and Schreiber2012, 187). After PCRM lost local elections in 2007, there were several attempts to elevate the relationship given the growing popularity of more radically pro-European opposition and concerns about further losses, including to some emerging rivals who portrayed themselves as equally – if not more – capable of enlivening interchanges with the Kremlin.

In 2009, PCRM lost power to the Alliance for European Integration (AIE), which was comprised of the Liberal Party (whose deputy head was Dorin Chirtoacă) and three other parties. Until 2017, when Chirtoacă was detained by authorities, Moldova went through two more AIE iterations, followed by a Pro-European Coalition (CPE), and a Political Alliance for a European Moldova (APME). During this period, the ruling coalition parties were oriented toward the European Union and the West in general, with few high-level contacts with Moscow. Tensions came to a head in 2014, when Chișinău ratified the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the European Union, which again bred several sanctions and an expansion of Moscow’s relationship with Transnistria (Stercul Reference Stercul2020, 31).

Since 2005 there has been a near consensus among Moldovan elites about European integration.Footnote 7 The ruling PCRM in 2007–2009 declared its support for European integration during its fifth congress (December 11, 2004) and campaigned on this goal in 2005 (Partidul Comuniștilor din Republica Moldova 2020), depriving the pro-European and pro-Western opposition of a major campaign narrative that year. In 2007–2009, therefore, one of Chișinău’s strategic foreign policy directions was European integration, which was enhanced after 2009, when parties with fewer connections to and interest in a strategic relationship with Russia took power and sought to speed up European integration. Throughout this period, the major disagreement was not about the strategic foreign policy direction itself, but about disagreements both within PCRM and the various pro-European alliances after 2009 about the speed and the depth of reforms required by the Association Agreement and the DCFTA.

Finally, Moldova’s diplomatic relationship with Romania during this period was affected by the political identity of the groups in government. PCRM’s relationship with Romania in 2007–2009 was informed by the party’s rejection of the Romanian identity of the majority population in the country and continuing accusations of Romanian irredentism, which permeated nearly all aspects of the bilateral agenda at the time, including the opening of additional Romanian consulates in Moldova, the status of the Romanian Orthodox Patriarchy, and a cross-border agreement (Chirilă Reference Chirilă, Șarov and Ojog2009, 30–31). The conflict culminated in PCRM’s accusations that Romania fanned violent anti-government protests in April 2009, which prompted the imposition of a visa regime with the country and the expulsion of the Romanian Ambassador. Ties were mended after PCRM lost power and, in 2010, Chișinău and Bucharest signed a strategic partnership for Moldova’s European integration (Tăbârță Reference Tăbârță2020, 18). The bilateral relationship has been prominent thenceforth, with the major difference within ruling alliances hinging on the extent to which parties acknowledged and promoted Romanian identity and unification. Whereas virtually all members of the ruling coalitions in 2009–2017 acknowledged the Romanian identity of the majority population, unionist rhetoric was primarily disseminated by the Liberal Party (PL) and some members of the Liberal Democratic Party (PLDM), with the Democratic Party (PD) positioning itself as a more pragmatic group in relation to what it defined as controversial and unnecessarily divisive identity questions.

Dorin Chirtoacă’s Foreign Policy

Chirtoacă entered Moldovan politics in the early 2000s as the vice president of the Liberal Party (PL), whose 2005 platform reflected the views described earlier (Partidul Liberal, April 24, 2005). On July 10, 2005, running on this platform, Dorin Chirtoacă announced his candidacy for the Chișinău mayoralty for the first time, placing third with 7.13 percent of the vote. The election was invalidated because of low turnout and Chirtoacă refused to participate in repeat elections two weeks later, which were invalidated for the same reason. Chirtoacă ran again during repeat elections on November 27, 2005 and December 11, 2005, which were again invalidated. During these two elections, Chirtoacă placed second after the ruling PCRM-supported candidate, gaining more visibility in both municipal and national politics. In 2007, the mayor won his first election, with 61.17 percent of the vote in the second round, and was reelected in 2011 and 2015.Footnote 8 Throughout his time in office, Chirtoacă’s foreign policy activities reflected a consistent focus on the European Union and Romania, which dominate the majority of all three major measures of diplomatic actions. In his ten years in office, Chișinău city hall reported no Chirtoacă visits to Russia, with the exception of a layover at the Domodedovo airport that will be described below. Contacts with other former Soviet republics are sparse, as well, with interactions mostly with Belarus, Georgia, and Ukraine.

Chișinău city hall reported 45 visits abroad during Chirtoacă’s time in office (see Figure 1). Of those, 13 were to Romania, by far the most visited single country. The mayor also visited European Union countries 19 times. A total of 32 out of 45 visits, therefore, have been to either Romania or the European Union. The mayor only visited the former Soviet Union four times during this period: Belarus twice and Georgia twice. The mayor’s office reported no visits to Russia during his ten years in office, which is a striking finding. In fact, the only visit abroad related to Russia was during a layover at the Moscow Domodedovo airport, when the mayor lay flowers at the site of a terrorist attack at the airport. No Russian officials were present at the event, and city hall published one picture with the mayor putting the flowers down at the memorial. The mayor also visited Israel, the U.S., Turkey, and Switzerland twice each, as well as China once.

Figure 1. Dorin Chirtoacă’s visits abroad.

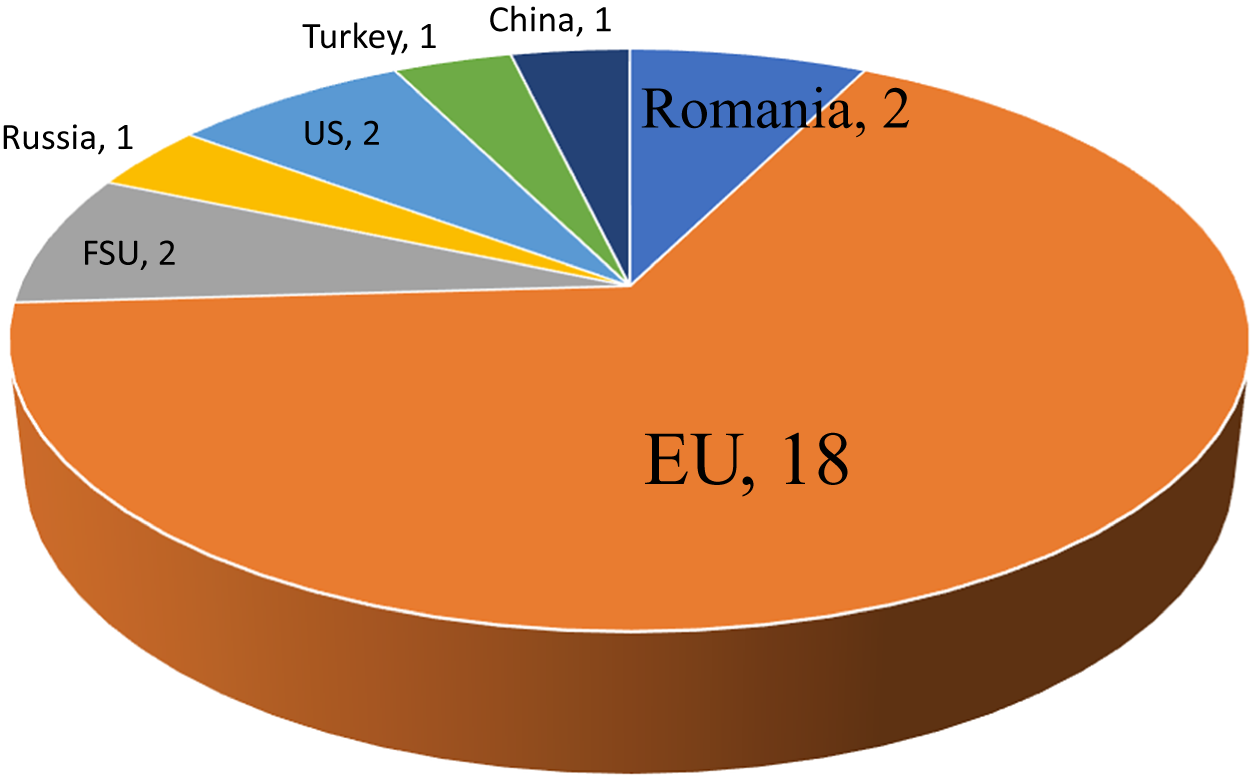

Chirtoacă met with Ambassadors accredited in Moldova for a total of 27 times (see Figure 2). Most of the meetings were reported in 2007–2009 (23), during a flurry of activities at the beginning of his term in office. By far, the number is dominated by meetings with Ambassadors representing the European Union or individual EU countries (18 out of 27 times). Chirtoacă also met with a Romanian Ambassador twice and with Ambassadors from Belarus (once), Ukraine (once), the U.S. (twice), Turkey (once), and China (once). Finally, the mayor met with the Russian Ambassador once during his time in office. Once again, the data reveals the overwhelming dominance of EU countries in the mayor’s meetings.

Figure 2. Dorin Chirtoacă’s meetings with Ambassadors.

During his time in office, Chirtoacă met 69 times with a variety of foreign delegations (see Figure 3). Romanian and EU representatives dominate in the dataset. The mayor met 13 times with Romanian national officials and seven times with Romanian local officials. He met five times with local officials from the EU, four times with national officials from an EU country, four times with EU-level officials, five times with business delegations from an EU country, and five times with European Union individuals not affiliated with government institutions. Consequently, Romanian contacts were tallied at 20 and EU contacts were tallied at 23. The mayor’s other prominent meetings were with representatives from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank (five times each). The mayor also met with two delegations of Russian local officials (one from Saint Petersburg and the other from Moscow) and four times with Georgian, Belarus, and Ukrainian local delegations.Footnote 9 The “other” category includes meetings with delegations from PACE (twice) and once from the UNFPA, the IMF, the International Association of Francophone Mayors, La Francophonie, IFC, and the European Gymnastics Federation.

Figure 3. Dorin Chirtoacă’s meetings with other delegations.

Beyond the description of the data, which reveals an overwhelming focus on Romania and the European Union and little contact with post-Soviet and Russian contacts, the content of these diplomatic actions reflects Chirtoacă’s consistent promotion of a foreign policy throughout his ten years in office.

In June 2007, shortly after taking office, Chirtoacă’s first official visit abroad was to Bucharest, where he met his counterpart Adriean Videanu and Romanian President Traian Băsescu. The mayor was later criticized by some pro-Russian city council members for meeting the Romanian President before the Moldovan one (British Broadcasting Corporation 2007b). Subsequent visits frequently took on a symbolic dimension as the mayor vocalized narratives about Romanian identity and unification as major reasons for the gatherings. In January 2008, after the Chișinău city council (CMC) approved a protocol for a sister-city agreement with the Romanian city of Iași, Chirtoacă and his Romanian counterpart signed the agreement on January 24, 2008, during a day commemorating the unification of Romanian principalities in 1859 (the intention to draw on the symbolic nature of the date was articulated openly in a Chișinău city hall press release). During the signing ceremony, Chirtoacă referred to key events in the pan-Romanian imaginary, like the “bridge of flowers” (Costachie Reference Costachie2009) that emerged across the Prut after the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime in Romania: “We had bridges of flowers. Now we want European bridges and I hope this sister-city agreement is implemented to strengthen an even tighter connection between ‘us and us’” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, January 25, 2008).

At the end of March 2008, Chirtoacă visited Bucharest, Iași, and Suceava and attended events celebrating Romanian unification on March 27, 1918. The mayor met his Bucharest counterpart Adriean Videanu and Sector 3 mayor Liviu Negoiță, as well as President Băsescu and Romanian Orthodox Church Patriarch Daniel. During a meeting with President Băsescu, Chirtoacă handed the head of state a picture of the members of the Moldovan Sfatul Țării, the legislative body that voted for Basarabia’s unification with Romania in 1918, adding that “Sfatul Țării voted for unification 90 years ago. I would like for it to be an example for what will happen in the future” (Monitorul de Suceava 2008).

Pan-Romanian rhetoric and symbolism did not abate during Chirtoacă’s time in office. On December 1, 2011, the mayor visited the Romanian city of Alba Iulia to sign a sister-city agreement. Both the date and the city itself were meaningful: December 1 is Romania’s National Day, and Alba Iulia is the location where the unification agreement, which included most of what is today the Republic of Moldova, was signed in 1918. The sister-city event itself was held in the Unification Hall in the Alba Iulia mayoralty, as Chișinău city hall reported (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, December 1, 2011). During his second term in office, in a meeting with Romanian President Traian Băsescu in July 2013, Chirtoacă thanked Romania for helping Moldova’s European integration, adding that “there are visible and very important results for this piece of land, which has been tortured and has suffered for 200 years” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, July 17, 2013). The reference to “200 years” echoes pan-Romanian rhetoric that defines the annexation of Basarabia by the Russian tsarist empire in 1812 as a turning point in the country’s separation from the rest of the territory populated by Romanians, and would have been a reference that PL and Chirtoacă supporters, along with anyone well-versed in Moldovan historical narratives, would have understood easily.

Chirtoacă’s pan-Romanian and unionist rhetoric also manifested itself in another foreign policy direction: his contacts with members of the Romanian Royal House.Footnote 10 In September 2013, the royal family granted the Order of the Romanian Crown to the Chișinău mayor. During the ceremony, Chirtoacă referred to the need for Moldova “to return to the European family, to return to the Romanian family, which would correct the injustice done in 1940, with the annexation of Basarabia to the Soviet Union. This event has convinced me, once again, that it would be much better if we had one single state, one single king, and one single law” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, September 11, 2013).

Alongside the promotion of unionist and pan-Romanian messages, Chirtoacă also portrayed Romania as a model of Europeanization for Chișinău, which challenged narratives at the central level that rejected Romania’s offers to mediate Moldova’s European integration.Footnote 11 During a January 2010 meeting with Romanian President Traian Băsescu, the mayor said that Chișinău was interested in using the experience of Romanian cities to adopt European standards and gave the Romanian head of state “a symbolic mandate to represent our country until we become a full member of the European Union” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, May 10, 2017).

At the level of diplomatic connections, the mayor endeavored to bypass central authorities to establish direct networks with Romanian cities and other institutions, which was plain while the Party of Communists (PCRM) was in power in 2007–2009. In 2009, during a meeting with the Romanian Foreign Minister, the mayor asked authorities in Bucharest to support city hall’s endeavors to make it easier for Moldovan residents to receive Romanian citizenship, a policy opposed by central authorities (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, June 26, 2009). Corina Fusu, the head of the PL faction in the Chișinău city council and a close ally of Mr. Chirtoacă’s in city hall, articulated a similar endeavor explicitly after the mayor attended a meeting of the League of Local Officials from the PDL party in Bucharest: “After the signature of the cooperation agreement between PDL and PL, the Foreign Relations Department at the Chișinău city hall sent all mayoralties in Romania led by PDL a list with our needs regarding the implementation of joint cultural projects between Chișinău and Bucharest: the structuring of direct projects between mayoralties that would not be mediated by the Communist government. We are not interested in the hostile interference of the Communists” (Partidul Liberal, August 12, 2008). The mayor also attended, alongside dozens of other mayors from Moldova, the first edition of the Forum of Local Authorities in Romania and Moldova, hosted in the Romanian city of Piatra Neamț in 2009, seeking to establish an institutional network in which mayors from both countries interacted without mediation by central authorities in Moldova.

Chirtoacă’s diplomacy toward Romania both undermined and supported central foreign policy priorities during his time in office. In 2007–2009, the PCRM-dominated central government’s bilateral relationship reached a nadir. After Bucharest sought to simplify the procedure to grant Romanian citizenship to Moldovan residents, requested the opening of two new consulates in the country, and suggested that it would be willing to manage a center for issuing EU visas, the Moldovan government issued a statement in March 2007 in which it accused the neighboring state of “undermining national security and the principles of statehood” (Basa-Press, March 7, 2007; Chirilă Reference Chirilă, Șarov and Ojog2009, 29). President Vladimir Voronin echoed similar critiques during a visit to Brussels, when he accused Romania of not recognizing Moldova’s statehood (Chirilă Reference Chirilă, Șarov and Ojog2009, 30). The Moldovan government later expelled two Romanian Embassy diplomats (IPN 2007b) at the end of 2007, and, in 2009, President Voronin accused Romania of direct involvement in the anti-Communist protests in April, expelled the Romanian Ambassador, reinstated visas for Romanian citizens, restricted border travel, and recalled the Moldovan Ambassador from Romania (Cimpoeșu Reference Cimpoeșu2010, 342; Ivan Reference Ivan2012, 6–7).

In short, the central government’s policy toward Romania during this period was characterized by diplomatic conflict, criticism of Bucharest’s policies in international forums, and the absence of consistent bilateral contact (see Cimpoeșu Reference Cimpoeșu2010, 344) to compel Bucharest to refrain from what it perceived to be attacks on its sovereignty. Chirtoacă’s actions undermined all of these policies as he used the mayoral institution to interact repeatedly with Romanian officials and to vocalize affinity with the neighboring country. Whereas the central government’s goal was to isolate itself from and pressure Romanian authorities to end pan-Romanian rhetoric, Chirtoacă eroded the consistency of these policies by, instead, further consolidating ties and vocalizing that rhetoric at the local level.

As a result, PCRM officials clashed with Chirtoacă over his relationship with Romanian representatives: in October 2007, during Chișinău’s City Day (hram) celebrations, Chirtoacă accused the government of preventing a number of Romanian delegations from entering the country to attend events in the Moldovan capital. Moldovan Foreign Minister Andrei Stratan subsequently said that authorities would investigate the controversy after Bucharest criticized the event as a “hostile act” (Radio Europa Liberă 2007) and after Chirtoacă announced that no other delegations from other countries had difficulties entering the country.

In addition, in August 2008, Chișinău city hall reported that Chirtoacă would be meeting with Romanian President Traian Băsescu, who was scheduled to visit the Moldovan capital (IPN 2008). The meeting never happened: Deutsche Welle reported that President Voronin asked his Romanian counterpart to cancel his meeting with the Chișinău mayor (Călugăreanu Reference Călugăreanu2008). Finally, in 2009, PCRM criticized Chirtoacă for being a “unionist mayor” and for attending an event in Iași celebrating the 150th anniversary of the unification of Romanian principalities, suggesting that the mayor had ties with the far-right Noua Dreaptă organization (IPN 2009a). These scuffles created difficulties for PCRM because Romanian authorities often looked to Chirtoacă as a major intelocutor who accepted Romanian narratives about Moldova and confirmed the existence of a strong pan-Romanian movement in Chișinău. Consequently, the Communist claim that such views belonged to a fringe group that lacked popularity was undermined by Chirtoacă’s continuing victories in city hall.

After PCRM left power in 2009, Chirtoacă’s diplomatic actions toward Romania no longer undermined the foreign policy goals of the center. In April 2010, after a new pro-European coalition took power (which included Chirtoacă’s PL), Moldova and Romania signed a joint statement on a strategic partnership for Moldova’s European integration (Tăbârță Reference Tăbârță2020, 18), followed by an agreement for a 100-million-Euro Romanian grant. The two countries initiated projects to connect gas and electricity networks, open a major branch of the Romanian Cultural Institute in Chișinău, and open a Moldovan branch of Romania’s TVR public television station (Tăbârță Reference Tăbârță2020, 22–23).

In large part, the mayor’s foreign policy, which continued along the same lines described above, was not inconsistent with what Chișinău was promoting at the center. Chirtoacă’s – and PL’s – foreign policy was more emphatic about Romanian identity and pan-Romanian messaging than the other coalition partners, but the narratives never gave rise to the same critical reactions seen in 2007–2009. In fact, shortly after PL moved into the opposition, Romanian President Traian Băsescu visited Chișinău again to meet with central authorities and had no difficulties meeting with Chirtoacă, who recommended that the head of state apply for Moldovan citizenship “to continue the battle from the other shore of the Prut” (IPN 2013).

In ties with the European Union, Dorin Chirtoacă’s city diplomacy centered on staking out a claim for Chișinău as a main driver of European integration in the country: during a January 2010 meeting with Romanian President Traian Băsescu, for example, Chirtoacă said that Chișinău was “the locomotive of Moldova’s European integration” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, January 27, 2010). This emphasis on Chișinău’s European identity was accompanied by Chirtoacă’s systematic request that the EU establish direct dialogue with the Moldovan capital to speed up the process of Europeanization. During a visit to Brussels in May 2008, the mayor explicitly asked for “direct cooperation” between the European Commission and municipalities in EU neighbor-states, arguing that “this would contribute to demonopolizing the takeover by the government of the Republic of Moldova of European funds and would ensure competition between the central and local administration in the organization of European projects in our country” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, May 16, 2008). The demands sought to convince European authorities to grant direct access to funds and the mayor successfully managed to secure funding from both the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank, with whose representatives he met several times.

In 2008, city hall implicitly criticized central authorities by announcing that “discussions between municipal authorities and representatives of the European Union’s financial institution took place for the first time after five years” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, July 11, 2008). After signing a loan agreement in 2010 with the EIB and the EBRD to buy trolleys for the capital, Chirtoacă explained that the agreement was possible “because of the implementation of several reforms in the Chișinău municipality in the last three years” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, October 13, 2010) and during a ceremony to sign an EBRD/EIB funding project to rebuild roads and install public lights, the mayor noted that “the new project to fix roads, just like the previous one to buy 102 trolleys, brings European standards here, in Chișinău” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, September 12, 2012).

At an international level, the mayor claimed the mantle of leadership in European institutions, portraying himself as a pro-European leader whose competence was endorsed by Brussels and speaking for expanding ties between the members of the Eastern Partnership and the EU. He became co-President of the Conference of Regional and Local Authorities in the Eastern Partnership (CORLEAP) in May 2012 and traveled extensively as the organization’s representative. He also became a member of the CORLEAP bureau in 2014, was a rapporteur for the Council of Europe’s Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, and was elected as the Vice President of the Chamber of Regions in the institution. In a May 2013 speech in Brussels, the mayor pushed for more direct EU funds for local governments in the Eastern Partnership and more fiscal decentralization “to achieve strong local democracy and continue the European path in Eastern Partnership countries” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, May 16, 2013).

Moreover, Chirtoacă took on the task of a watchdog of European modernization, urging central authorities to be consistent in the implementation of reforms demanded by the EU and occasionally criticizing them. In 2012, for instance, the mayor asked the Secretary General of the Council of Europe’s Congress of Local and Regional Authorities to ask authorities to enact “all recommendations from European partners by 2014, in order to give local public authorities full autonomy. [ … ] The implementation of the recommendations of the Council of Europe is a test of seriousness for the Republic of Moldova, and potential failures will no longer have any explanations” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, March 22, 2012).

In a July 2013 speech at the four ministerial meeting of the Eastern Partnership, Chirtoacă – whose PL was in opposition to the government at this point – accused central government officials of “taking advantage of the lack of European standards in our country,” adding that Eastern Partnership countries “must not only simulate the implementation of reforms, delay this process, or behave in the opposite manner, like is happening in the case of decentralization” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, July 23, 2013).

Chirtoacă’s self-ascribed role as a watchdog of European integration was apparent during his diplomatic actions in the wake of violent anti-government protests and a repression campaign organized by PCRM against demonstrators in April-May 2009 (Amnesty International 2009). The mayor was active in publicizing evidence of police abuse of protesters during a May 2009 visit to the United States and was explicit in his criticism of central authorities during a 2009 meeting with a European Parliament delegation: “Lack of respect by the government of the Republic of Moldova for fundamental European and international values can no longer be tolerated” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, April 28, 2009).

Central Moldovan authorities rarely reacted as critically to the mayor’s European diplomatic affairs as PCRM did regarding Chirtoacă’s diplomacy toward Romania in 2007–2009. By 2005, virtually all major political parties in Moldova, including the Party of Communists, committed publicly to European integration as a strategic objective and asked that the country be granted EU candidate status.Footnote 12 In light of general consensus over the country’s European integration, Chirtoacă largely echoed central government messages, with the exception of the events surrounding April 2009, when he was much more critical of central authorities.Footnote 13 In fact, in March 2012, mayor Chirtoacă met with President Nicolae Timofti, who said that he hoped the executive would “continue to cooperate [with the mayor] to reach the country’s strategic objectives,” which included European integration (IPN 2012). Chirtoacă’s burgeoning relationship with Brussels, therefore, matched the center’s foreign policy direction: Moldova was included in the EU’s Eastern Partnership in 2009 and negotiations on visa-free travel, an Association Agreement, and a free trade agreement were finalized successfully in 2013 (Tabirta 2020, 9). At times, Chirtoacă criticized central authorities for enacting European reforms too slowly, but both local and central authorities were in agreement about European integration as a priority.

Dorin Chirtoacă’s diplomatic affairs toward the post-Soviet world were rather sparse, on the other hand, focusing primarily on an agreement with authorities in Minsk for the construction and assembly of trolleybuses (a major mode of public transportation in the city). When in contact with other post-Soviet states, like the signature of a sister-city agreement with Tbilisi (Georgia) and a visit to Chișinău by a delegation led by the Tbilisi mayor, Chirtoacă framed contacts in a pro-European context, as well: “The pro-European visions of the two mayors come from the soul and there will be sustained efforts for the European dream to become a reality for both Moldova and Georgia” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, July 11, 2013). Even when he did visit countries in the former Soviet Union, Chirtoacă mostly did so to attend European Union events: in October 2010, the mayor attended a Conference of European Mayors in Tbilisi on October 21–22, where he also met with the deputy mayors of the cities of Bishkek and Smolensk (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, October 22, 2010). During that same visit, the mayor met with Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili to discuss “the evolution of democratic reforms” in both Moldova and Georgia (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, October 22, 2010).

The mayor did meet with Russian delegations from Moscow (July 2007) and Saint Petersburg (November 2012), as well as the Russian Ambassador (September 2007), which were typically laconic and focused on statements about bilateral associations. The mayor said during his meeting with the Saint Petersburg delegation, for instance, that he was “happy that ties of cooperation between Chișinău and cities in the former USSR are beginning to be rebuilt” (Primăria Municipiului Chișinău, November 21, 2012) and spoke with the Russian Ambassador about reviving a cooperation agreement with Moscow – with no apparent follow-up during Chirtoacă’s ten years in office. At times, the mayor also criticized Russian authorities: in September 2011, Chirtoacă accused Russian premier Vladimir Putin of “spitting in the face” of Moldovan officials after congratulating Transnistrian authorities on 21 years of the separatist region’s independence. The mayor added that Russia’s defiance of Moldova’s independence and territorial integrity “seems to have been constant for at least 20 years, if not 200, since the first occupation” (IPN 2011).

In the case of the post-Soviet area and Russia, Chirtoacă’s foreign policy was characterized more by inaction than action, consistent with his prioritization of the relationship with Romania and the EU. Such an approach had two major consequences for the center’s foreign policy during the mayor’s tenure in office. In 2007–2009, inaction undermined efforts by central authorities to buttress ties with Russia at the local level. This policy had been established by PCRM when it first came to power in 2001 and signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with Russia (TMAE335/2001 2021). Article 10 in the treaty emphasized the “establishment and maintenance of contacts” between Moldovan and Russian administrative units in areas like the economy, cultural, and humanitarian ties. Indicative of these goals, in 2008, for instance, prime minister Vasile Tarlev met in Moscow with mayor Yuri Luzhkov and agreed to create a working group to deepen cooperation (Point.md 2008 ). The meeting with the Russian mayor was particularly conspicuous since Luzhkov and the short-lived PCRM-supported interim mayor of Chișinău (Veaceslav Iordan) had met just a few months before Chirtoacă took office (IPN 2007a). The mayor’s sparse interactions with post-Soviet and especially Russian actors stood, therefore, in contrast with PCRM’s attempt to augment cooperation at the local level. In this regard, inaction had a similar effect to action involving Romania: it contradicted and weakened the enactment of a set of central foreign policy-making goals.

After 2009, however, Chirtoacă’s inaction about Russia was consistent with the center’s foreign policy toward Moscow. The ruling coalitions, which PL joined occasionally during Chirtoacă’s tenure, prioritized contacts with the European Union as ties with Russian authorities became secondary. In 2012, the country did not even have an official Ambassador to Russia for most of the year (Expert-Grup 2013, 43), and, after the country signed the Association Agreement with the European Union in 2014, Russia reimposed trade restrictions on some Moldovan products (Expert-Grup 2014, 48; Expert-Grup 2015, 43). In 2017, authorities banned Russian deputy premier Dmitry Rogozin from entering the country for “unfriendly, denigratory, and offensive statements and public comments about the Republic of Moldova and its people” (Digi24 2007). From this standpoint, Chirtoacă’s minimal contact with Russian authorities, as he preserved ties with the EU and Romania, dovetailed with the main direction of the center’s foreign policy.

Conclusion

This article’s key arguments are that mayors in the post-Soviet world are influential foreign policy actors in their own right and can either obstruct or fortify central foreign policy goals. Dorin Chirtoacă’s experience illustrates these points: the mayor promoted a consistent set of diplomatic goals, rooted in his political beliefs, with a major emphasis on Romanian and EU contacts and a de-emphasis of relations with the post-Soviet states. Both the mayor’s actions and inactions undermined or supported the center’s foreign policy goals, depending on the degree of consensus between local and national foreign policy priorities.

In fact, the inductive exercise has yielded a preliminary typology of sorts that could help scholars refine both the types of foreign policy activities and the impact of these activities on the center’s foreign policy goals. Mayors can engage in actions consistent with their own goals, which may either undermine or support the center’s foreign policy goals. Mayors may also deemphasize action or may not act, which could also either dovetail with the center’s hierarchy of goals or compromise a goal by diluting its implementation at the local level. The proportion of these various categories in a mayor’s diplomatic activities will likely vary by the characteristics of individual mayors, the nature of leadership at the center, and the distribution of resources across administrative levels, to name a few potential variables. Importantly, Dorin Chirtoacă was the mayor of a city that dominates Moldovan politics and therefore had both the resources and the visibility of a major political figure; his actions and inactions inevitably had more impact than those of a smaller city or village.

Some of the insights of this inductive exercise may also be limited by the specificities of the case that has been selected: Moldovan political elites continue to debate the ethnic identity and the name of the language of the majority population (Moldovan or Romanian), the nature of the impact of the country’s experience as part of both Romania and the USSR in the 20th century, and the question of whether Moldova’s foreign policy should look primarily to the East or the West (Anderson Reference Anderson2005; Botan Reference Botan, He, Kulik and Lawson2010; Cash Reference Cash2007). The country is therefore particularly prone to debates on national and ethnic identity, historical narratives, language controversies, and geopolitical choices that involve other states, including those claiming kin affiliations. Such debates are rife in the post-Soviet world, and additional case studies would help further refine how and whether they have an impact on a country’s foreign policy. A more comprehensive analysis of mayoral diplomacy would also incorporate the motivations, beliefs, and goals of the local and national officials from the countries with which mayors are interacting. Romanian officials clearly preferred to interact with Chirtoacă instead of national-level officials (in 2007–2009) because the mayor agreed with and vocalized pan-Romanian narratives shared by the former. Similarly, Russian representatives may not have been interested in ties with the mayor, bearing in mind his frequent criticism of Russian foreign policy in Moldova, which is why a sizable number of interactions may not have even been possible. Mayors are, indeed, agents with a degree of autonomy and a set of separate foreign policy goals, but their endeavors will often depend on the interests and goals of other actors. A mayor may therefore try to continue or establish connections abroad, but willing interlocutors are indispensable for such endeavors to materialize.

Overall, the findings above problematize the continuing state-centrism of post-Soviet foreign policy studies and encourage the incorporation of a relevant diplomatic agent – the mayor – who can either challenge or buttress the center’s foreign policy. Mayors will not always matter in foreign policy, but a research agenda with the mayor at its heart would present a more complex – but more accurate – picture of foreign policy in the post-Soviet area.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michelle Sabourin, Derek Glasgow, the participants at the International Studies Association-Midwest conference in 2019, the anonymous reviewers, and the editor for their comments on previous drafts of this manuscript. All mistakes are my own.

Disclosures

None.