Introduction

Why and how could politicians of religious minority background assume the highest political offices, such as president and prime minister, in some countries after their transition to modern nation-states with representative institutions, whereas in some other countries, almost all the highest political offices have been occupied by politicians from the religious majority background for decades if not centuries? Second, why are the leading politicians of religious minority backgrounds almost exclusively limited to the leftist (liberal or socialist) party traditions in some countries, whereas one finds prominent nationalist leaders of religious minority backgrounds in some other countries? Third, and finally, why do some countries that started out with a nationalist political leadership affiliated with the majority religion change to include nationalist and conservative political leaders of religious minority backgrounds later? This article seeks to contribute to the scholarship on democracy, nationalism, and religious identity by answering these interrelated questions.

The Puzzle: The Stark Variation in Religious Identity of Political Leaders

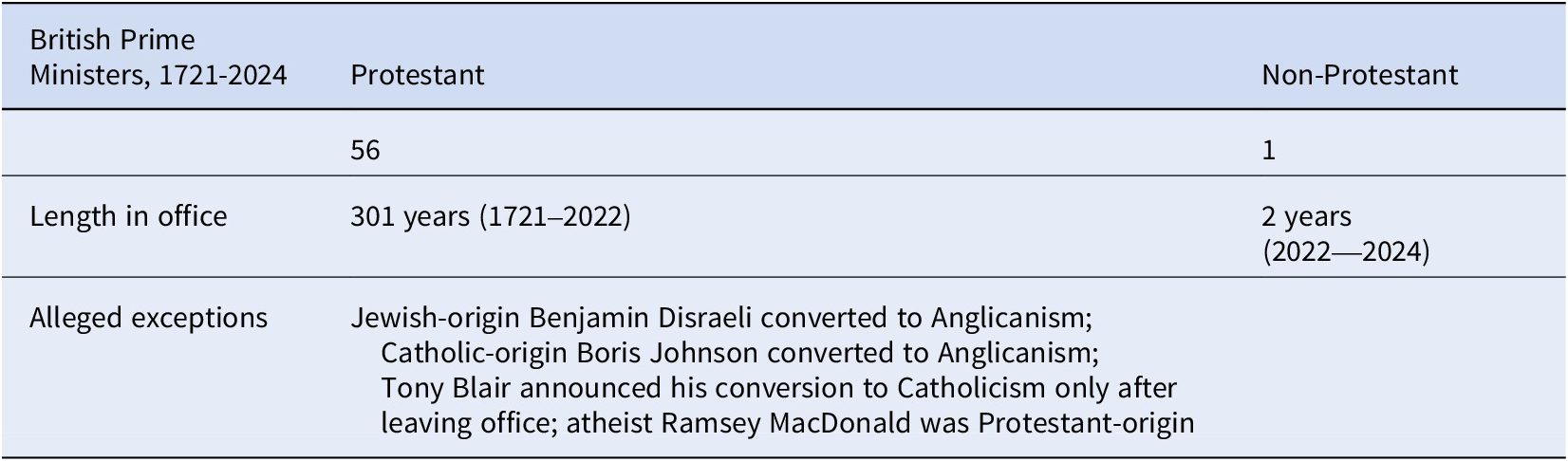

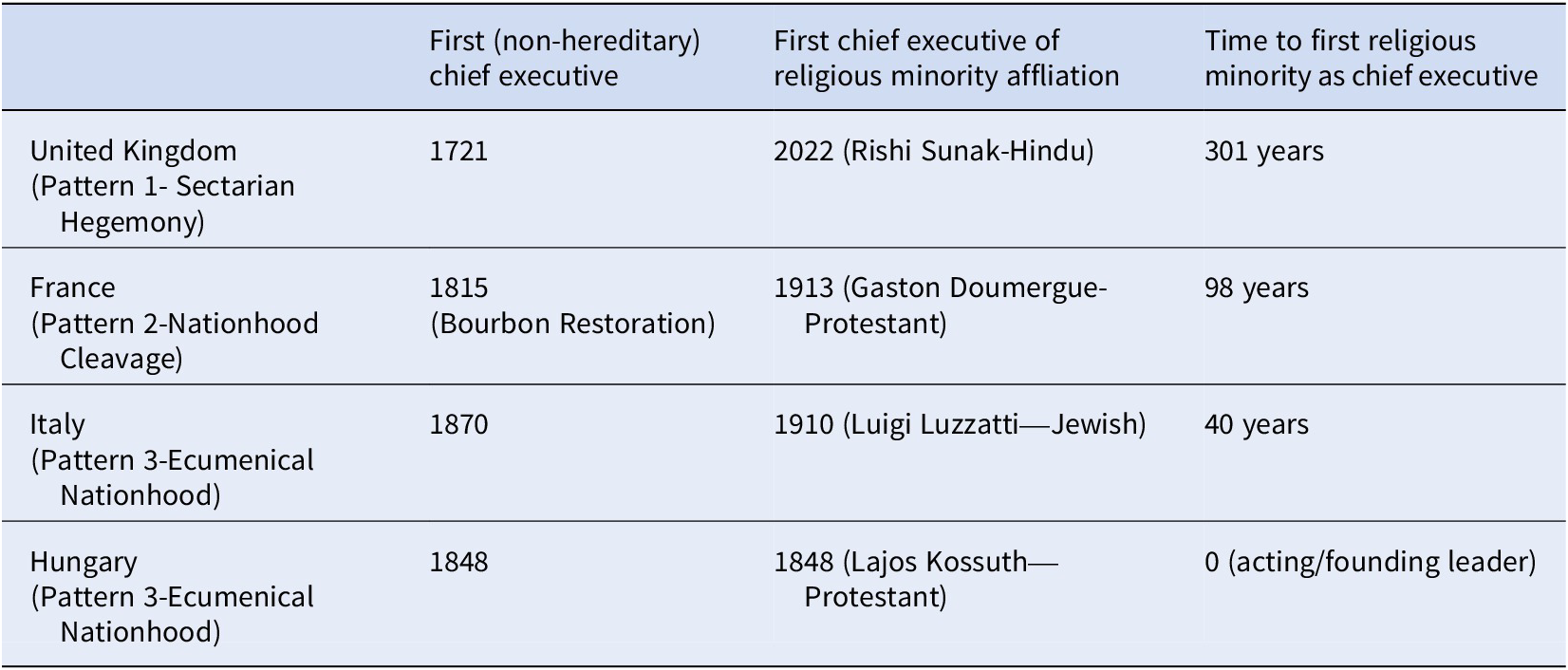

The UK, the oldest and arguably the most consolidated modern democracy, only had Protestant prime ministers for three hundred years from the creation of this office in 1721 (Seldon Reference Seldon2021) to the selection of Rishi Sunak as the leader of the Conservative Party in October 2022, which made him the prime minister without a popular election. Thus, it took 301 years for the UK to have a chief executive espousing a religion other than Protestantism. Moreover, all the heads of state and monarchs have been Protestant by law, including the current monarch, King Charles III. Unlike Conservative Sunak, the first Catholic, Jewish, and Muslim members of the parliament have all been affiliated with the Liberal (Whig) and Labour parties.

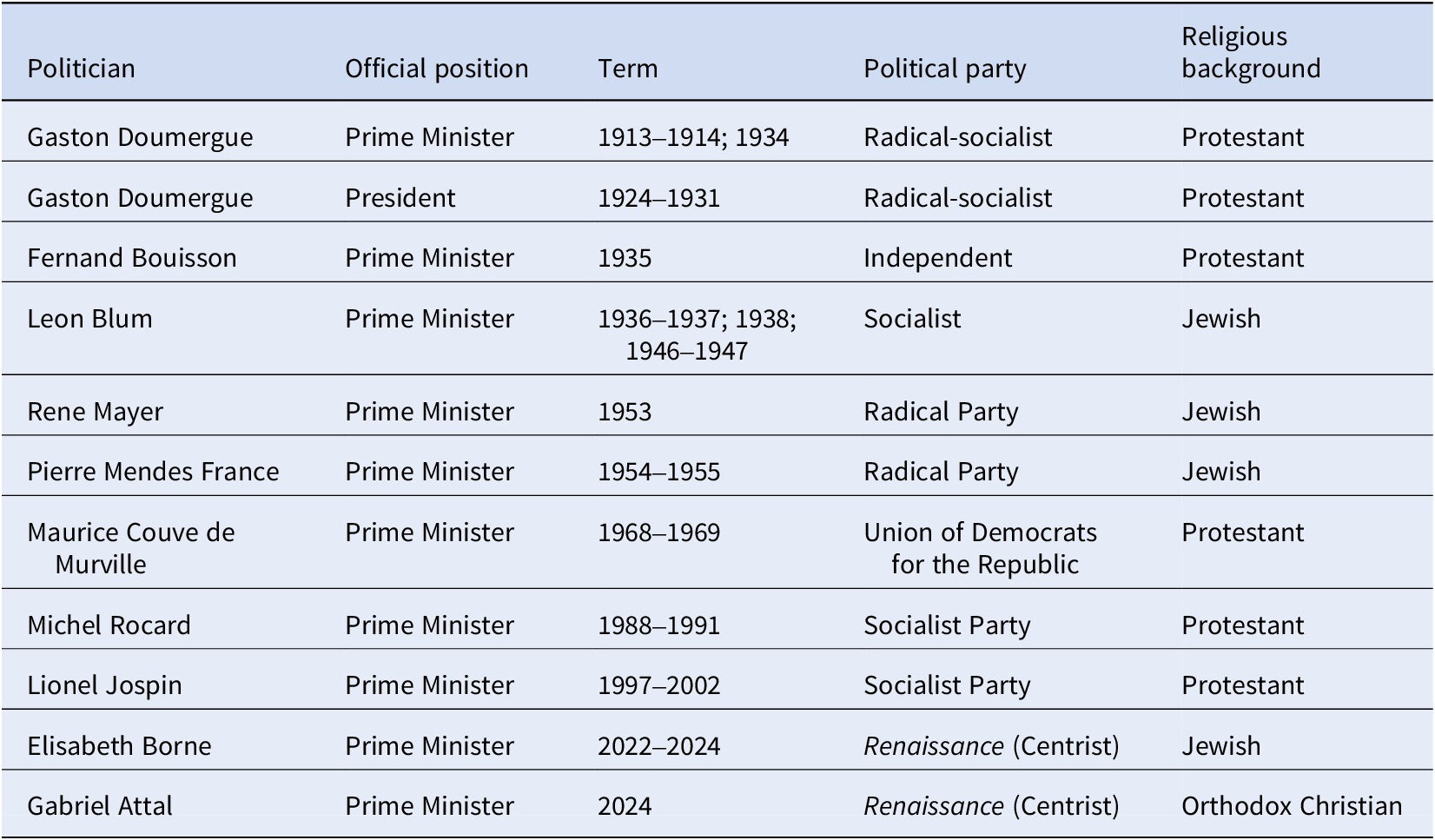

France, praised by one scholar as “the only country in the world, apart from Israel, that has several times chosen as its leader a Jew openly proclaiming his identity” (Birnbaum Reference Birnbaum2015, 4), did have several Jewish and Protestant prime ministers despite being from a Catholic-majority. Almost all the Jewish and Protestant French prime ministers have been leftists and often socialists. Not only Jews and Protestants, but the largest number of Muslim members in the French parliament have also been from leftist parties (Aktürk and Katliarou Reference Aktürk and Katliarou2021). Hungary, which also has a Catholic majority both historically and at present, by contrast, has had nationalist leaders hailing from its Protestant minority, including Viktor Orban, the longest-serving prime minister of Hungary (from 1998–2002 and 2010–present) and probably the most prominent popularly elected Hungarian politician in recent history. Moreover, Katalin Novak, the president of Hungary from 2022 to 2024, was also a Protestant. Italy, which has a more overwhelmingly Catholic majority than Hungary, had a well-known Jewish prime minister in the early 20th century, Luigi Luzzatti. According to some, Italy also had another Jewish prime minister, Alessandro Fortis (Fisher Reference Fisher2019). Thus, Italy is an earlier example than France in having Jewish politicians assuming national political leadership (Catalan and Facchini Reference Catalan and Facchini2015). Both Hungary and Italy had religious minority politicians from the center-right and nationalist traditions as national leaders.

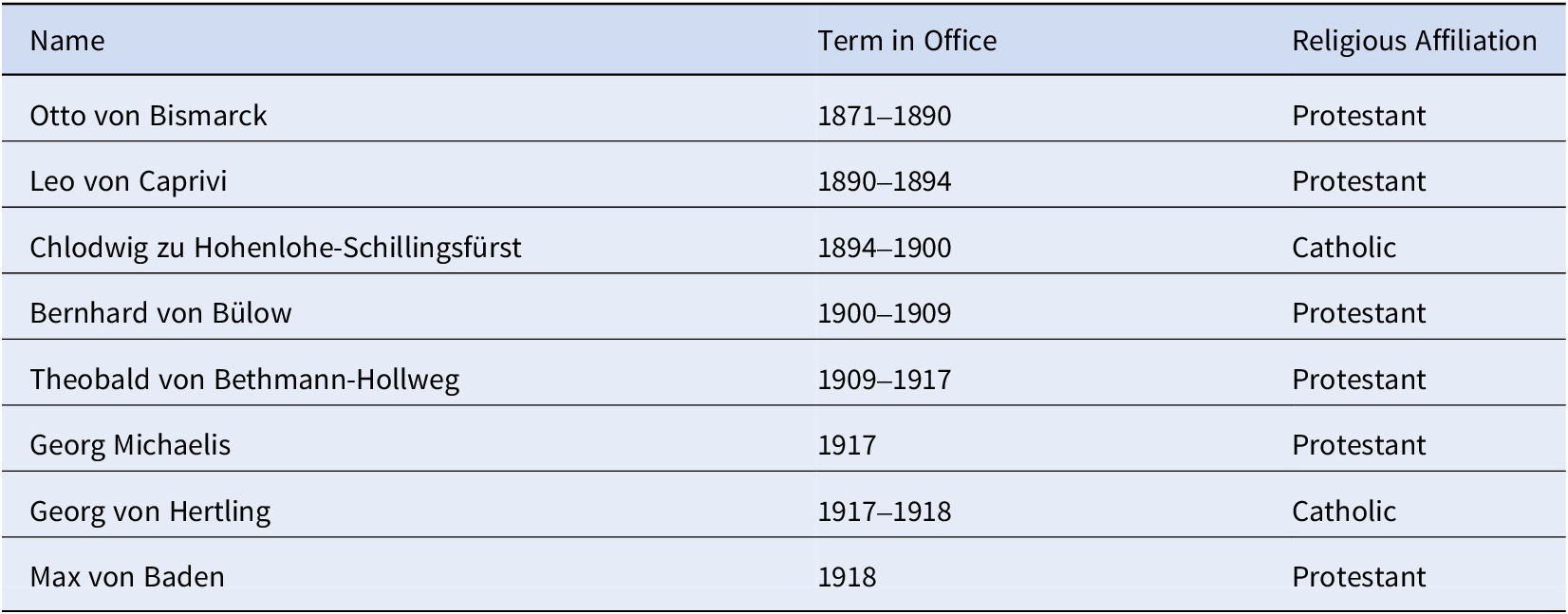

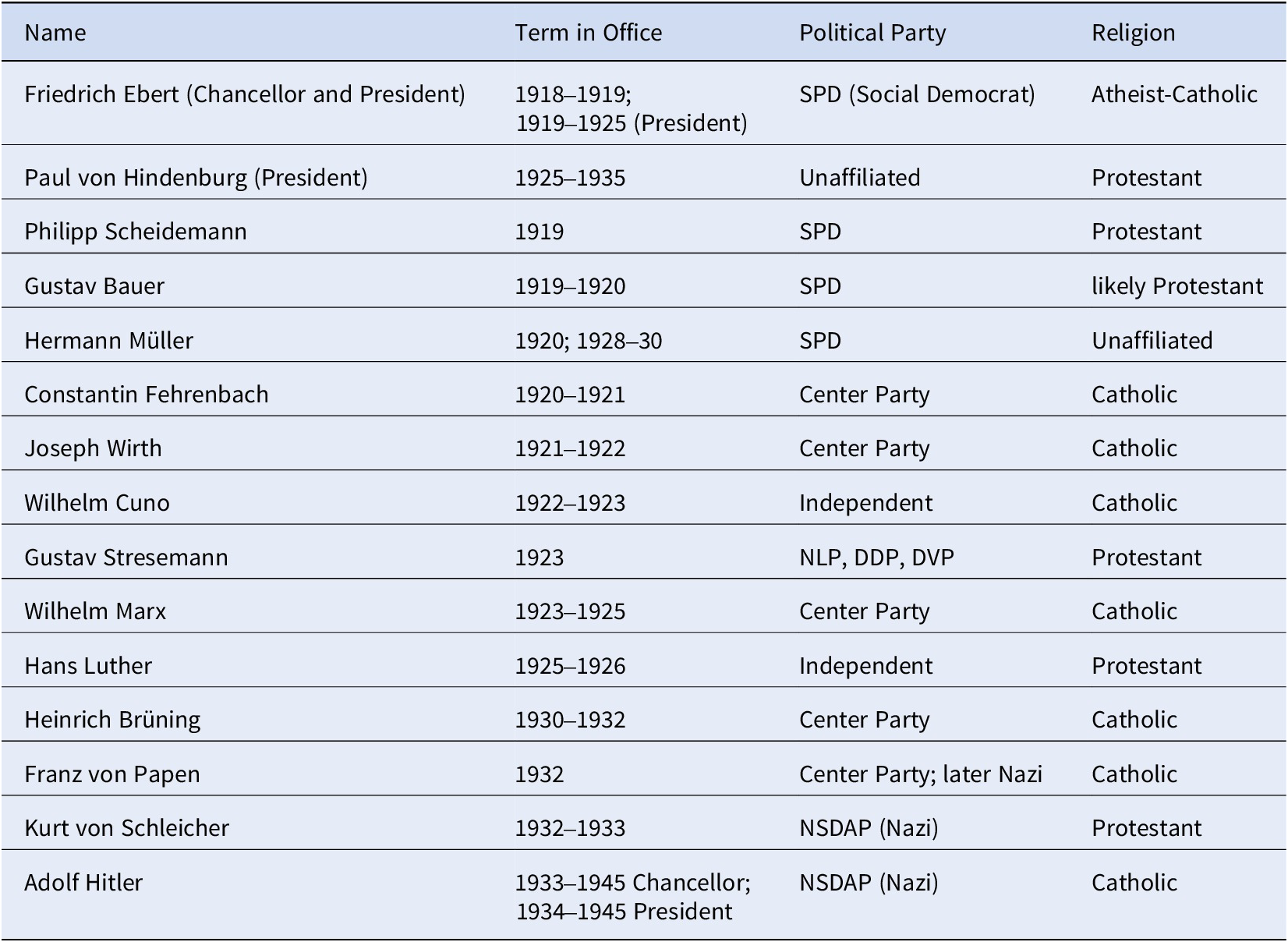

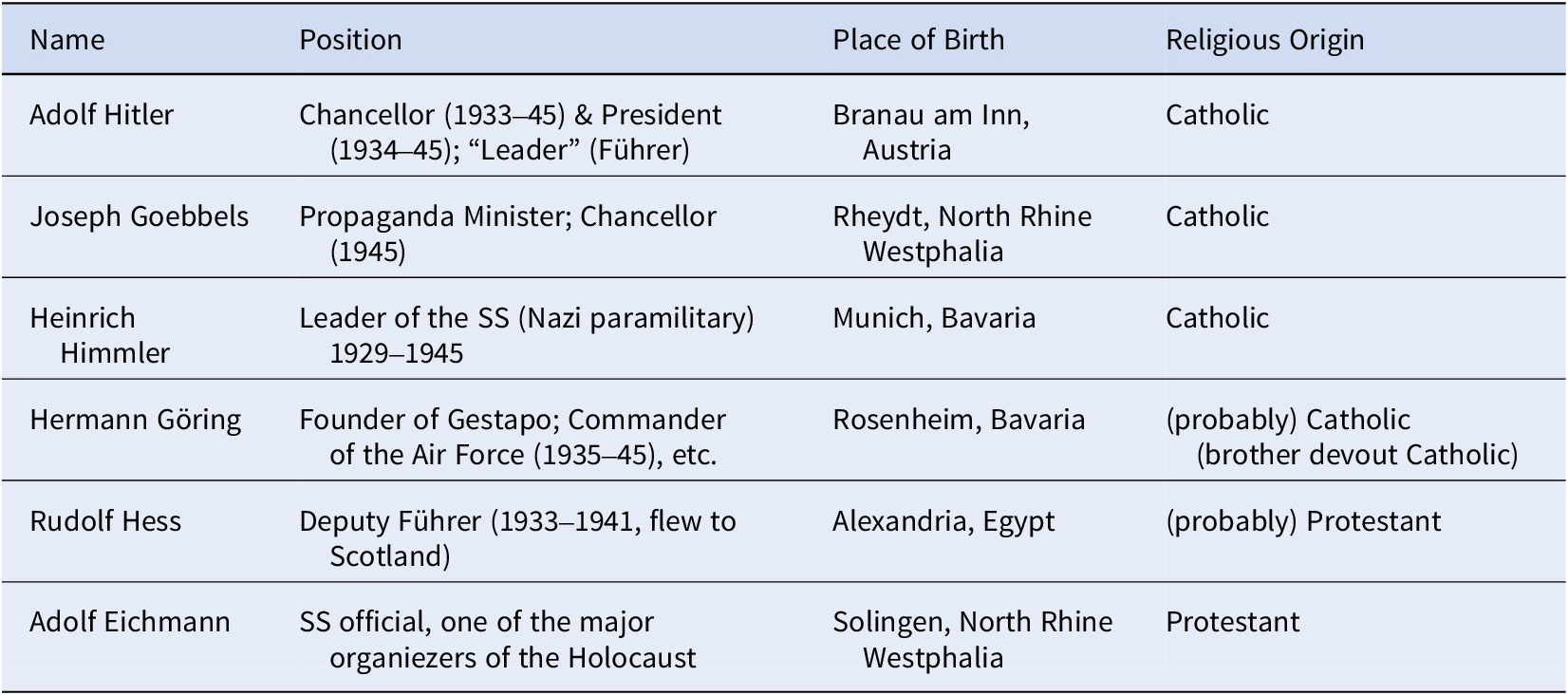

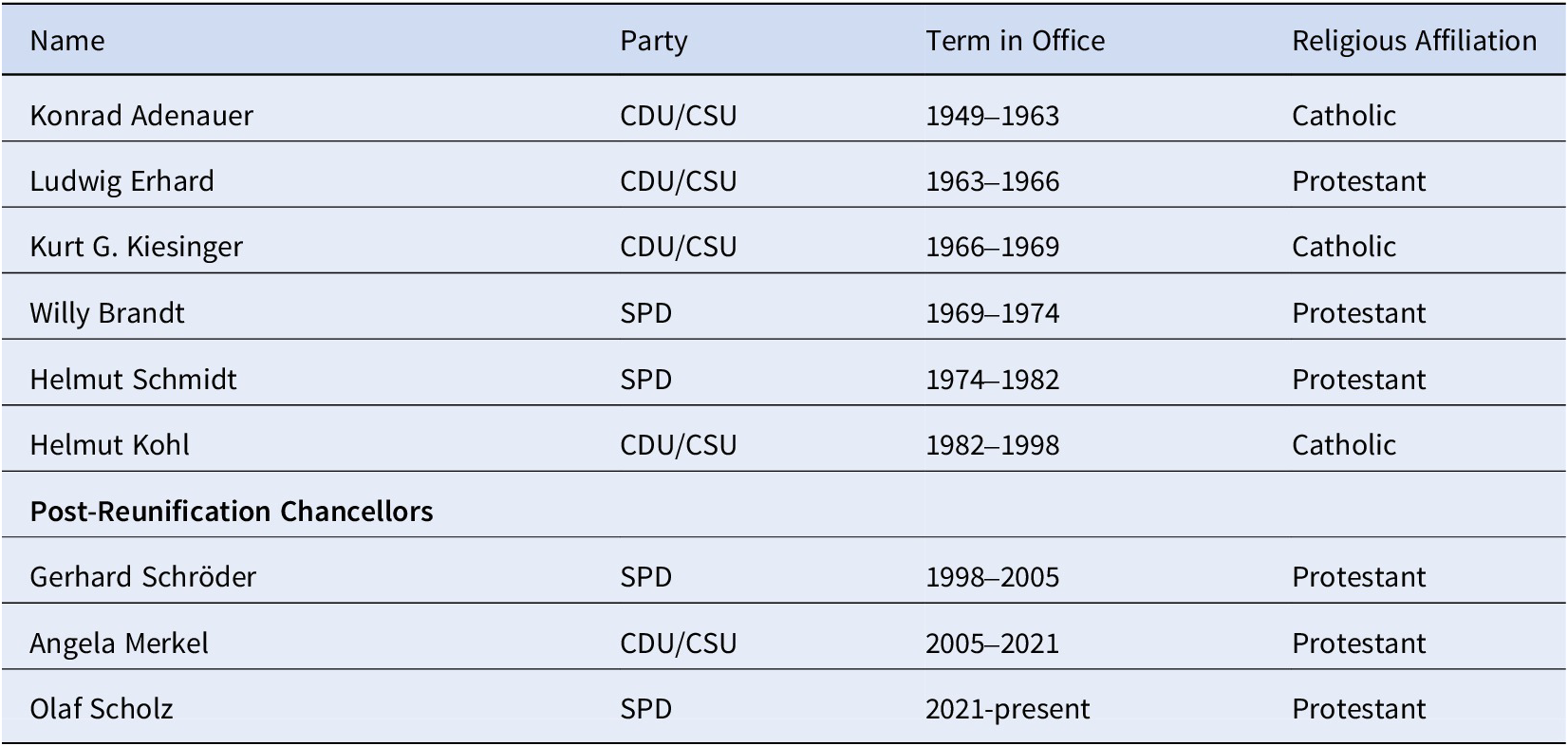

How resilient are these three patterns and is change between them possible? “Path dependence” is a well-known feature of historical legacies and institutions (see, for example, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer Reference Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003; Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006; Reference Wittenberg2015). Are there cases where a nation-state that started out with the political hegemony of a specific religious sectarian core (almost always the demographic majority) changed so radically that the members of the previously securitized and marginalized religious sectarian minority assumed national and even nationalist political leadership? Indeed, Germany experienced such a radical trajectory. While Protestant figures (for example, Bismarck and Bethmann-Hollweg) dominated national leadership from German unification in 1871 until the end of Imperial Germany in 1918, this pattern changed and Catholic leaders (for example, Hitler) became dominant by the 1930s under Nazi Germany. Catholic leaders such as Konrad Adenauer were in power twice as long as Protestant leaders in postwar West Germany but this was likely a reflection of the Catholic-majority following Germany’s division, but German reunification in 1990 reversed the pattern once again and Germany has had three consecutive Protestant chief executives, starting with Gerhard Schröder as the first post-reunification chancellor in 1998.

What explains the cross-national variation in the first appearance and frequency of religious minority politicians in national leadership? Relatedly, what explains whether politicians of religious minority backgrounds attain national leadership as liberals, socialists, or nationalists? Third, what explains when a country changes paths with a radical alteration in the religious background of its national leaders? I argue that these three puzzles are related and explained by the nature of the constitutive conflict that established the nation-state.

The article proceeds as follows. Following the current section introducing the puzzle from a comparative perspective, the second section reviews the extant scholarship on religious minorities’ participation in national politics in order to identify the predictions and evaluate the usefulness of existing explanations for my empirical puzzle. It is important to note that there is no existing theory that seeks to explain my specific empirical puzzle. My specific puzzle is the incidence of a religious minority politician representing the nation as the highest chief executive, which is a rather rare phenomenon from a comparative perspective. My puzzle is essentially and theoretically different than the representation of religious minorities alone because the assumption of the highest level of national leadership is about the ability to represent or “embody” the nation as a whole, rather than a specific minority alone.

The third section explicates my argument in detail. The fourth, fifth, and sixth sections discuss causal mechanisms, research design, case selection, measurement, relevance, and limitations of my argument. The seventh section discusses the pattern of a sectarian hegemony exemplified by the first modern democracy and the first nation-state, the UK. The eighth section discusses the pattern of nationhood cleavage exemplified by France. The ninth section discusses the pattern of ecumenical nationhood exemplified by Hungary and Italy. The tenth section presents Germany as an example of a radical change in the religious sectarian background of national leadership over time. The eleventh section looks beyond these five European nation-states to the universe of independent nation-states that existed for more than a century and finds that the few cases where religious minorities assumed national leadership, such as Albania and Peru, are indeed cases where the nation-state was established in a secessionist struggle against an imperial rival with the same religious identity, which confirms my theoretical argument’s predictions. The recent and historic cases of religious minority leadership in Mexico, Scotland and Ukraine also provide dramatic confirmations of my argument. The final section recaps the contributions of the argument and its relevance for the studies of democracy, identity politics, nationalism, and religion.

Extant Scholarship on Religious Minorities in National Politics: Liberal Democracy, Secularization, Protestantism, Demography, and the Leftist Parties

Religious cleavages were the fundamental fault lines of European politics and society for many centuries, ever since all Jews and Muslims across Western Europe were eradicated under papal-clerical pressure through a mixture of expulsions, massacres, and forced conversions (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2024). Starting in the early 16th century, conflict between Catholics and Protestants became the fundamental fault line of European politics and society (Terpstra Reference Terpstra2015). Arguably every European nation-state had a religious sectarian core group (for example, Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant) and the other religious groups were marginalized, persecuted, and securitized (see, for example, Marx Reference Marx2003). Under such conditions of centuries-old marginalization and securitization, how do religious minority politicians rise in national politics? There is no existing theoretical argument that seeks to answer the exact comparative question posed in this article, namely, how and when the religious minority politicians reach the peak of the national leadership. However, there are various scholarly accounts of political representation with implications for religious minority representation in national politics.

First, one prominent “whiggish” narrative about religious toleration and minority representation charts a progressive expansion of political representation as a result of liberalism. The following depiction of Lionel Rothschild’s admission to the House of Commons as the first British Jewish legislator is a succinct example of this liberal narrative:

This triumph over restrictive traditions had advanced by liberal assertion to fundamentally alter the religious character of Parliament, with rights to be represented and to serve as representatives having moved first from an Anglican to a more broadly Protestant frame, then from a Protestant to a Christian one, and finally, with Jewish rights, to become a trans-Christian legislature. (Katznelson Reference Katznelson, Katznelson and Jones2010, 62).

According to this argument, modern nation-states begin with a narrow religious sectarian core, and then in successive progressive expansions of the franchise, necessitated by liberalism or democracy or both (liberal democracy), these polities move from the representation of only specific (for example, Anglican) denominations to a broader sectarian (for example, Protestant) representation, followed by the representation of Christian minorities (for example, Catholic or Eastern/Orthodox) and, finally, the representation of non-Christian minorities (for example, Jews and Muslims). Other arguments mirror this narrative of liberal democratic emancipation, including Christian Joppke’s (Reference Joppke2005) thesis that liberalism led to the end of ethnic-national quotas in immigration and citizenship.

The liberal democratic narrative on minority emancipation is contradicted by the empirical record. The polities that had religious minority politicians as chief executives very early on, such as Hungary and Italy, were less liberal democratic than Britain, which did not have any chief executives of religious minority background for centuries. Even if one restricts the analysis to the common paired comparison between Britain and France, the polity that is considered less liberal democratic, France, was the one that had multiple Jewish and Protestant minority politicians as chief executives whereas Britain did not have any Catholic or Jewish chief executives. The two paradigmatic cases that inspired the “whiggish” liberal democratic narrative, the UK and the USA, experienced waves of electoral disenfranchisement that followed their democratic origins (Bateman Reference Bateman2018). Moreover, liberalism and democracy correlated with more racist and exclusionary citizenship and immigration policies (Fitzgerald and Cook-Martin Reference FitzGerald and Cook-Martin2014) that suppressed the political representation of non-Christians. In sum, liberalism and democracy, if anything, appear to be correlated with the exclusion and disenfranchisement of religious minorities.

Second, one may expect levels of secularization to determine religious minorities’ upward mobility in politics, with the lowest levels of religiosity enabling religious minorities to assume the highest executive leadership, as religion becomes socially more insignificant. Comparative empirical patterns contradict such predictions based on secularization. British society is very secular, where “less than one million regularly attended a church service by 2020, with just 2 percent of ‘young adults’ calling themselves Anglican,” which has historically been the official religion (Seldon Reference Seldon2021, 204). Yet, Britain only had Protestant-heritage chief executives for 301 years until 2022, even though Protestants were less than half the population already in 2010 (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2018, 56, Table 1). By contrast, Italy, with an overwhelmingly Catholic majority and high levels of religiosity in the early 20th century had a Jewish prime minister, Luigi Luzzatti. Hungary, a bastion of Catholicism historically, had Protestant national leaders, such as Lajos Kossuth, already in the 19th century, if not earlier.

Table 1. Protestant hegemony: British prime ministers’ religious affiliation, 1721–2024

Third, there could be specific religious legacies that discourage the rise of religious minorities in politics. Focusing on Muslim minorities in 19 Western liberal democracies, Michael Minkenberg (Reference Minkenberg2018) argued that accommodation of cultural group rights of religious minorities is significantly lower in Catholic countries compared to Protestant countries:

Predominantly Protestant countries exhibit moderate to high levels of cultural group rights recognition whereas Catholic countries fall in the range of low to moderate levels… In sum, there is no Protestant country where group recognition is low, and no Catholic country where it is high. (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2018, 62)

Minkenberg’s argument is not about minorities in politics, but an implication of his argument may be that Protestant-heritage polities would be more receptive to the rise of religious minority politicians than Catholic-heritage polities. Such a hypothesis contradicts the empirical pattern of religious minority chief executives: Catholic France, Hungary, and Italy, had multiple religious minorities as chief executives since the early 20th century, whereas Protestant Britain did not have a religious minority chief executive for over 300 years. The USA, the largest Protestant country in the world, only had two non-Protestant chief executives (John F. Kennedy and Joe Biden) in over 240 years. Neither Protestant country had a Jewish chief executive, whereas Catholic France and Italy both had.

Fourth, leftist parties are often identified as the main channels for religious minority politicians (Dancygier Reference Dancygier2017; Aktürk and Katliarou Reference Aktürk and Katliarou2021). This claim parallels the pattern of the three oldest democracies, since the highest profile Jewish and Catholic politicians in the UK and the USA, and the highest profile Jewish and Protestant politicians in France, have been from leftist political parties. Thus, the prediction would be that leftist governments would carry religious minority politicians to be their chief executive, as happened with John F. Kennedy and Joe Biden, the only two non-Protestant presidents of the USA. However, this argument does not explain the examples of Hungary or Italy. Both Prime Minister Orban and President Novak are from the same conservative nationalist, right-wing political party tradition in Hungary, and Prime Minister Luzzatti belonged to the nationalistic right in Italian politics, while “most Italian Jews in the interwar period supported Fascism” and “welcomed Mussolini, first as an antidote to socialism, and later for his colonial conquests” (Klein Reference Klein2018, 2, 11). Similarly, the first non-Protestant British prime minister, Rishi Sunak, has been the leader of the Conservative Party. As this necessarily brief overview demonstrates, the existing scholarly accounts fail to explain the cross-national variation in the national leadership of politicians of religious minority backgrounds. I argue that a more convincing explanation of this variation may be found in the nature of the constitutive conflict that established the nation-state, which is discussed in the next section.

The Argument: The Constitutive Conflict of Nation-Building Shapes the Opportunities of Religious Minorities for National Leadership

I argue that the political opportunities of religious minorities are very significantly shaped by the constitutive conflict that established modern nationhood. I argue that if the main adversary in the constitutive conflict that established the modern nation-state had a religion different than the majority religion in the nation (for example, Protestant Britain versus Catholic Spain), then the majority religion (for example, Protestantism in Britain) is likely to be identified with the nation (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2022), and it is comparatively more difficult for religious minority politicians to assume national leadership. In such a scenario, religious minorities in general (for example, non-Protestants in Britain), but especially the religious minorities that have the same religious affiliation as the national adversary in the constitutive conflict (for example, Catholics in Britain), are highly likely to be securitized and excluded. In the second pattern, if the polity suffered a major domestic constitutive conflict such as a civil war or a revolutionary upheaval that led to an ideological split over national identity, the religious minorities are likely to be able to assume national leadership positions in the leftist political parties while being excluded and even demonized by the right-wing parties. In the third pattern, I argue that if the main adversary in the constitutive conflict that established the nation-state was of the same religious tradition as the national majority (for example, Catholic Hungary versus Catholic Austria), then it should be easier for the religious minority politicians to assume national leadership because religious minorities will not be securitized. In such a setting, it is even possible that the religious majority (for example, Catholic Hungarians) may be securitized as potential collaborators and traitors who may side with the national adversary (for example, Catholic Austrians) out of religious affinity, which would make religious minorities (for example, non-Catholic Hungarians) as potentially more reliable and steadfast nationalists.

In addition to the nature of the constitutive conflict, a secondary factor that is also important for religious minorities’ political fortunes is the extent to which the majority religious tradition in the country is doctrinally and institutionally national or supranational. If the majority religious tradition has a national institutionalization such as the Lutheran national churches in Scandinavia or if it has an ethnic doctrine such as Hinduism and Judaism with hereditary religious distinctions (for example, Brahmin, kohanim, etc.), then it is comparatively less likely for religious minorities to assume national leadership (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2022). In such a setting, not belonging to an ethno-nationally specific religion (for example, Anglicanism, Hinduism, Judaism, and Lutheranism) can be used as a reason to denounce minority politicians as not belonging to the nation. In short, I argue that national-religious configurations mostly shape (constrain or allow) the opportunity structure for religious minorities in national politics.

Correlation and the Causal Mechanisms: Logics of Different Constitutive Conflicts

Constitutive conflict is an example of a “critical juncture” often discussed in comparative historical analyses (Mahoney and Rueschemeyer Reference Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003). Constitutive conflict directly shapes the political opportunities of religious minorities and majorities by setting up a constitutional order that includes explicitly or implicitly religious requirements for the chief executive, which is a causal mechanism directly linking the constitutive conflict and the faith of the sovereign. The Anglican-Protestant “establishment” in Britain is a paradigmatic example of such a mechanism (Bateman Reference Bateman2018). If the constitutive conflict was against a rival of the same religious tradition (for example, Catholic vs. Catholic), then the majority religious identity may be securitized as potentially subversive, often through policies of radical secularization targeting the majority religion (for example, French revolutionary secularism against Catholic clergy). Another related mechanism is the establishment of gatekeepers for the nomination and selection of chief executives, which may favor a specific religious sectarian background. A third mechanism consists of the official rituals and symbols enveloping the office of the chief executive that may have religious sectarian connotations and thus would make candidates from particular religious sectarian backgrounds uncomfortable running for national leadership and for the voters to approve of such candidates for national leadership. Fourth, since the national chief executive is also the “commander in chief” in many countries, the “constitutive conflict” that established the nation-state is a particularly prominent and relevant narrative for the person seeking that office. Thus, politicians affiliated with “the enemy’s religion” in the constitutive conflict may be stigmatized as unfit for being “commander in chief” due to the religious framing of the constitutive conflict. The first two mechanisms are about the formal-legal eligibility and selection or approval by gatekeepers of candidates from above, whereas the third and the fourth mechanisms pertain to the candidates’ propensity to run for, and the popular propensity to vote for particular candidates seeking national chief executive office.

Research Design, Case Selection, and the Universe of Cases

The research design of this article is a heuristic case study in pursuit of theory building. “Heuristic case studies inductively identify new variables, hypotheses, causal mechanisms, and causal paths” (George and Bennett 2005, 75). Many social scientific works, including studies of ethnicity and nationalism, similarly focused on a small number of cases exemplifying different patterns rather than investigating the entire universe of cases. Liah Greenfeld’s (Reference Greenfeld1992) Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity, based on case studies of England, France, Russia, Germany, and the USA, is a well-known example of this genre. Anna Grzymala-Busse’s (Reference Grzymala-Busse2015) study of Canada, Croatia, Ireland, Italy, Poland, and the USA, Nations under God, and David Bateman’s (Reference Bateman2018) study of France, the UK, and the USA, Disenfranchising Democracy, are more recent works of heuristic theory-building focused on the interactions between religious identities and nationalism in Western Christian-heritage democracies. I mostly follow this social scientific tradition of heuristic theory building based on a small number of country-case studies embodying different political patterns. In the penultimate section, I briefly look beyond my primary cases to the universe of cases consisting of 56 nation-states where long-term patterns of chief executives’ religious backgrounds may be observed.

Faith of the Leviathan? Significance, Relevance, and Limitations of My Argument for National Pride, Public Goods, Demography, Religiosity, and Salience of Religion

Why does the religious identity of the chief executive matter? What is the religious identity of the national chief executive a case of? “Faith of the sovereign,” as the head of government and/or head of state, may be both a symbolic and a substantive embodiment of the religious identity of the nation. In the anthropomorphic symbol of the modern state coined by Thomas Hobbes (Reference Hobbes1985 [1651]), one may alternatively describe my outcome of interest as “the faith of the Leviathan.” It indicates whether a person of religious minority affiliation can “embody” and “represent” the nation as a whole, which includes being the “commander in chief,” and as such, it is the highest-level litmus test of the relationship between the conceptualization of the nation and the majority-minority religions. The religious identity of the national leader may also affect some decisions on religiously sensitive issues at the highest political level in the nation. The religious identity of the chief executive may also influence patterns of national pride among different religious groups. An interconfessional collective identity is demonstrated to influence levels of public goods provision (Singh Reference Singh2015). The religious identity of the national leader is also likely to influence different forms of volunteerism and sacrifice for the collective good, including the willingness to fight for the nation.

There have been very few national chief executives from the “non-core” (Mylonas Reference Mylonas2012) religious groups in the five European polities that this article focuses on, which is also the case in the other 51 nation-states included in my universe of cases. This finding demonstrates the executive hegemony of the core religious-sectarian group in most nation-states, similar to the pattern of “sectarian hegemony” observed in Britain. Germany is the only major European nation-state with an almost equal sectarian split between Catholics and Protestants demographically at present (see Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2018, Table 1 for the religious composition of 19 Western polities).

There are three important caveats of my argument that must be clarified to dispel any misunderstandings, which relate to demography, the “religiosity” of politicians, and the salience of religion and religious observance. First, almost all the American polities and a sizeable portion of the Western-Central European polities are overwhelmingly Catholic, thus making it unlikely to have a non-Catholic, let alone non-Christian chief executive from a demographic representational vantage point. Therefore, only a minority of countries within the universe of cases may be seen as theoretically plausible cases for the rise of a national leader from a religious minority. Such cases of demographic marginality also offer an opportunity in the form of a least likely case design: if a national leader of a religious minority background rises despite the demographic marginality of the minority (for example, from a “one percent” minority) and is correctly predicted by my theory based on the nature of the constitutive conflict, as in Italy, Mexico, Peru, Scotland, and Ukraine, then this would provide a particularly strong confirmation of my theory.

Second, my argument does not imply that political leaders of religious minority backgrounds are religious or religiously observant. On the contrary, there are theoretical reasons to think that religious minority political leaders would face the pressures of secularization more than the members of the religious majority, and hence they are more likely to be very secular in order to rise in national politics. In fact, many religious minority politicians do not appear to be religious at all (for example, Aktürk and Katliarou Reference Aktürk and Katliarou2021). What matters for my argument is their public perception as religious minority members especially in the eyes of the majority; it is the variation in the nominal affiliation of political leaders rather than their actual religious belief or behavior that I seek to explain.

Third and relatedly, the social salience of religious differences and religiosity is part of the dependent variable or the outcome that I seek to explain, and thus, cannot be part of the independent variable or the cause. It is often claimed that the Catholic-Protestant divide no longer matters in the highly secularized contemporary Britain, France, Germany, Hungary, and Italy that I focus on. First, if religious affiliations indeed lost their salience to the point of being irrelevant for national leadership, such a development indicates “desecuritization” of previously critical religious differences, which itself is the more general outcome of interest that needs to be explained. For example, if Roman Catholicism, which was highly securitized and seen as a “fifth column” in the early phases of German nation-building, especially during the state-led Kulturkampf against the Catholic Church, is “desecuritized” and no longer seen as a threat in postwar Germany, then this momentous transformation is part of the outcome that needs to be explained. By contrast, however, if the religious identities of the leaders are not salient and do not matter in these highly secularized societies, then the variations I described above, which are discussed in greater detail below, are even more puzzling. Why did only France and Italy have Jewish prime ministers in all of Western Europe? Why did Hungary have multiple nationalist leaders from its Protestant minority in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries? Why did Germany dramatically shift from a Protestant-heritage national leadership to a Catholic-heritage national leadership, starting in the 1930s? Why did Britain only have Protestant-heritage prime ministers for over three hundred years? The British case is chronologically and arguably causally prior to the others as the first democratic nation-state and the first case study that I turn to in the next section.

Pattern of a Sectarian Hegemony: Protestant Hegemony in Britain

In the first pattern, the national identity is established through a constitutive conflict against an archenemy of a different religious sectarian tradition (for example, Protestant vs. Catholic). Especially if such conflict is combined with a dominant religious tradition that has a national institutionalization (for example, “a national church”), then the result is most likely to be a “sectarian hegemony” of the core ethnoreligious identity (for example, Anglicanism) strongly reinforcing nationalism. In such a sectarian hegemony, it is most difficult for religious minorities in general and the religious minority that shares the religious affiliation of the archenemy in particular (for example, Catholics in Britain) to achieve national political leadership. The UK, arguably the first modern nation-state (Greenfeld Reference Greenfeld1992) and the first modern democracy, is the paradigmatic example of this pattern with its Anglican-Protestant establishment (Marx Reference Marx2003; Colley Reference Colley2009; Bateman Reference Bateman2018). To the extent that religious sectarian minorities achieve political leadership positions in a nation-state characterized by sectarian hegemony, they are likely to be found among those opposed to the conservatives, since the latter often are the defenders of the “sectarian establishment.”

Every British prime minister for 301 years from the establishment of this office in 1721 until 2022 has been of Protestant origin. Some of them have been non-practicing, with Ramsay MacDonald, the first prime minister from the Labour Party in British history assuming office in 1924, also being “the first prime minister to declare himself an atheist” (Seldon Reference Seldon2021, 204). Some others, “like Gladstone and Salisbury, were intensely serious about their faith” (Seldon Reference Seldon2021, 203). The few cases of prime ministers with non-Protestant affiliations at birth or later in life are also strong confirmation of my argument, since they converted to Protestantism long before ascending to the office of Prime Minister or waited until leaving office to publicly declare their conversion to a non-Protestant religion.

Jewish-origin Benjamin Disraeli converted to Protestant Christianity, in Disraeli’s case specifically to Anglicanism at the age of 12, well before having a political career and becoming prime minister. Tony Blair was Protestant when he became prime minister, and “due to political considerations,” he revealed his conversion to Catholicism only after he left office in 2007 (Bates Reference Bates2007). It was revealed that “the former prime minister formally converted to Catholicism in 2007,” after he relinquished his premiership (Simpson Reference Simpson2019).

Boris Johnson’s story resembles that of Disraeli due to his early conversion: although Johnson was baptized and raised Catholic as a child, “he was confirmed in the Church of England while studying at Eton College, effectively abandoning Catholicism for Anglicanism” (Catholic News Agency, 2020). Johnson’s conversion, as in the case of Disraeli’s, arguably made him eligible to become a prime minister later in life. Thus, Boris Johnson was the “first baptized Catholic to become prime minister,” but similar to Disraeli, he “was confirmed an Anglican [Protestant] while studying at Eton as a teenager” (Simpson Reference Simpson2019). Regardless of their religious affiliations as children or after they left office, all British prime ministers were publicly Protestant while in office, with a few non-believers of Protestant origin. No British prime minister has been an adherent of Catholicism, Judaism, Islam, or any other non-Protestant religion publicly while in office until 2022 (Table 1). Why do I count Disraeli, a Jewish-origin convert to Anglican Protestantism, as a Protestant, while I count MacDonald, a Protestant-origin atheist, as a Protestant? The principle of measurement is simple and universalizable: if a politician did not publicly convert to a different religion, he/she still counts as being affiliated with his/her original religious heritage. For example, Leo Varadkar, the Prime Minister of Ireland from 2017 to 2020 and from 2022 to 2024, was raised Catholic but was non-religious later in life, but he counts as a Catholic in terms of my measurement in this study since he did not publicly convert to a different religion.

This striking pattern was reaffirmed as late as September 2022, when Liz Truss, an Anglican Protestant, succeeded Boris Johnson as the prime minister, after defeating Rishi Sunak in a vote of the Conservative Party membership for party leadership. This 300-year pattern was finally broken with the resignation of Liz Truss in October 2022, when Rishi Sunak, a Hindu by religious affiliation, was selected to the party leadership once all of his likely opponents withdrew their candidacy. It is still noteworthy that Sunak did not become prime minister by winning a popular election, and he indeed lost the first national election that he contested as the leader of the Conservative Party in 2024. The head of state, the British monarch, is also Protestant (Anglican) by law and is the supreme governor of the Church of England, which was reaffirmed in May 2023 with the coronation of King Charles III, who took the oath with the “promise to maintain ‘the Protestant Reformed Religion’.” (Farley and Seddon Reference Farley and Seddon2023).

The Protestant monopoly in Britain over three centuries is inexplicable by numerous alternative explanations that would have predicted a non-Protestant prime minister well before 2022. First, Britain is arguably the oldest and most consolidated liberal democracy in Europe, if not in the world. Second, Britain is a significantly secularized society where 27.8 percent of the population was religiously unaffiliated as of 2010, which is almost exactly the same percentage as in France (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2018, 56, Table 1), and “less than one million regularly attended a church service by 2020, with just 2 percent of ‘young adults’ calling themselves Anglican” (Seldon Reference Seldon2021, 204). Third, the leftist Labour Party has been in government multiple times since the 1920s. Fourth, the historically dominant religious tradition is Protestantism, not Catholicism. Fifth, Britain’s Catholic minority is demographically much larger than France’s Protestant minority, and yet France had a number of Protestant prime ministers whereas Britain did not have a single Catholic prime minister. The Jewish minorities of Britain and France are comparable in size, yet France had several Jewish prime ministers but Britain did not have any. Sixth, the UK is almost universally considered as religiously more tolerant than France. For example, public expressions of Islamic religiosity are far more prevalent and tolerated in the UK than they are in France, where many Islamic religious expressions are prohibited by law. In short, many factors identified by different scholars as promoting the accommodation of religious diversity are present in Britain, and yet not a single non-Protestant became the chief executive for over 300 years. Moreover, there are numerous reasons to expect the UK rather than France to have more chief executives from religious minority groups, but the outcome has been the opposite.

My argument that emphasizes the national-religious configuration based on the original constitutive conflict of the polity offers a more plausible explanation for the British puzzle: a constitutive conflict of nation-building fought against adversaries belonging to a different religion, namely, Catholic France and Catholic Spain (for example, Marx Reference Marx2003; Colley Reference Colley2009), combined with a dominant religious tradition that has a national institutionalization, namely Anglicanism, as institutionalized in the Church of England, explains the fusion of Protestantism and British national identity.

Minorities’ Representation under Sectarian Hegemony via Liberal-Leftist Opposition

How do securitized religious minorities gain political representation under sectarian hegemony? How did sizeable populations of non-Anglicans, non-Protestants, and non-Christians participate in British politics? Britain’s two political traditions, Tories and Whigs, were both Protestant factions closer to Anglicans and Dissenters, respectively, and their ideological competition included accusing each other of being closer to Catholics, thus reinforcing the demonization of Catholics as the constitutive other, while depicting themselves as the true Protestants (Tumbleson Reference Tumbleson1998). Non-Protestant, primarily Catholic, and non-Christian, primarily Jewish and Muslim, political representatives concentrated as subordinate elements of the opposition, which corresponded to the Whigs and the Liberals in the late 18th and 19th centuries in the process of Catholic emancipation and its aftermath (Bateman Reference Bateman2018), and the Labour Party for most of the 20th and 21st centuries (Table 2).

Table 2. Non-Protestant political leaders and “pioneers” by party affiliation in Britain

Whigs and the Radicals, predecessors of the Liberal Party, led the three-pronged reform project including “the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts that excluded non-Anglican dissenting Protestants from local offices, passage of a Catholic relief or emancipation law that would allow Catholics to sit in Parliament and hold public offices and commissions, and passage of what would become the Reform Act of 1832, which reapportioned seats in Parliament and revised the qualifications for voting rights” (Bateman Reference Bateman2018, 207), summed up in their famous slogan at the time, “Civil and Religious Liberty, All Over the World!” (Bateman Reference Bateman2018, 233). By contrast, the Conservative Party, also known as the Tories, was and remained the main representative of the Anglican hegemony and Protestant sectarian character of the British state throughout the 19th century. “The bond between Anglicanism and the Tories/Conservative Party, and between non-conformity and the Liberals, slowly waned in the twentieth century” (Seldon Reference Seldon2021, 50), but as Table 2 demonstrates, almost all the political “pioneers” and “leaders” with a non-Protestant and non-Christian religious identity in Britain have been affiliated with the opposition to the Conservative Party, the Liberal, and the Labour parties. As the example of Tony Blair demonstrates, even leading politicians from the left/liberal camp conformed to the Protestant leadership pattern out of political tradition, which sets apart the British pattern of sectarian hegemony from the other patterns that are examined in this article.

Causal Mechanisms of Religious Selection in the British Case

Multiple potential causal mechanisms that may link the chief executive office to a core religion were observable for most of British history. First, there were legal requirements that limited membership in the parliament and many public offices to Protestants at least from the Glorious Revolution (1688) until the Reform Act of 1832 (Bateman Reference Bateman2018). Second, the existence of a constitutionally Anglican monarch as the head of state who would formally appoint the Prime Minister, open parliamentary sessions, and serve as “the commander in chief,” and several dozen Anglican Protestant bishops who serve as “Lords Spiritual” in the House of Lords, the upper chamber of the parliament, are but two examples of Anglican Protestant privilege preserved in the political system. Third, the “Popish plot” of 1678, and the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, which is still commemorated in Britain, are examples of the public rituals that reproduce the “Catholic other” as the archenemy. “Catholicism acted as the demonized antagonist in opposition to which English nationalism first crystallized” (Tumbleson Reference Tumbleson1998, 17). Such public rituals are likely to discourage Catholics from seeking the national leadership of the nation. Especially given the paucity of all alternative explanations, my argument based on Britain’s constitutive conflict and nationalized religion may plausibly explain why 56 prime ministers over 301 years from Robert Walpole in 1721 until Liz Truss in 2022 have been nominally Protestant or Protestant-origin nonbelievers.

In another causal mechanism combining political gatekeeping with historically rooted anti-Catholic national discourses, aspiring Catholic politicians note their irritation at the deployment of anti-Catholic tropes during their selection by fellow party members. Kevin Meagher, who self-identifies as “a Labour loyalist,” relates the following experience:

When I went for a parliamentary selection some years ago my experience was one of stark opposites. I found lots of Catholic party members who instinctively cleaved towards someone with a similar worldview. Then there were those who did not. ‘I suppose you’ll be standing by the phone waiting to take your orders from the Pope?’ I was asked. ‘Of course I will’ I replied, ‘but I expect he’ll email these days.’ It’s irritating to have to justify your faith…. (Meagher Reference Meagher2015)

Catholics continue to be scrutinized for their religious beliefs after being elected. In another striking example, although the majority of Catholics vote for the Labour Party, in an op-ed titled “Cardinals’ sins” in 2008, Labour politician Mary Honeyball criticized Catholic ministers in the Labour government, Ruth Kelly, Des Browne, and Paul Murphy, for their religious preferences, alleging that they put the papal opinion above national interests, going as far as questioning whether devout Catholics should serve in British governments: “Should devout Catholics such as Kelly, Browne, and Murphy be allowed on the government front bench in the light of their predilection to favor the Pope’s word above the government’s?” (Honeyball Reference Honeyball2008; also quoted in Meagher Reference Meagher2015) In partial conclusion, the British case provides examples of multiple causal mechanisms preventing the rise of religious minorities, and especially members of the largest religious minority, Catholics, to national leadership: constitutional-legal measures (for example, Test and Corporation Acts), gatekeepers (for example, Anglican monarch, Lords Spiritual, etc.), public rituals and commemorations casting doubt on religious (Catholic) minorities (for example, the Gunpowder Plot), and pervasive discourses of subversive religious minorities as fifth columns (for example, Catholics’ alleged loyalty to the pope).

Nationhood Cleavage Pattern: Religious Minorities in Leftist Opposition in France

In the second pattern, in polities where the constitutive conflict of nation-building was against adversaries of a different religious sectarian tradition (for example, Catholic vs. Protestant), a major episode of internal violence such as a revolution or a civil war led to a “nationhood cleavage,” one of the two major political traditions, usually the leftist-secularist one, is identified with religious minorities in competition with a conservative-nationalist right-wing tradition, and the religious minorities may assume political leadership of the leftist-secularist political parties. This pattern is particularly likely if the domestic constitutive conflict (for example, civil war or revolution) was along a religious-secular faultline and pitted the secularist/leftist faction against a dominant religious sectarian tradition that is supranational in its institutionalization (for example, the Catholic Church). France is arguably the most influential example of such a nation-state transformed through internal strife, and other polities that experienced revolutionary violence or civil war are likely to exemplify this pattern.

France is often favorably compared to most other European countries for being the first country to emancipate Jews following the French Revolution, depicted as “Europe’s most democratic nation” (Berman Reference Berman2019, 123) and praised by Pierre Birnbaum as “the only country in the world, apart from Israel, that has several times chosen as its leader a Jew openly proclaiming his identity” (Birnabum 2015, 4). As I already noted, Italy had a Jewish prime minister earlier than France. Nonetheless, Birnbaum’s claim has some truth in that France had four Jewish chief executives, which is more than any other Western democracy, and it also had at least five Protestant chief executives Table 3).

Table 3. Non-Catholic origin Prime Ministers and Presidents of France, 1815-2024

France briefly transitioned to a republican form of government in 1792 with the First Republic, but it was within the context of a constitutional monarchy, starting with the Bourbon Restoration, that a non-hereditary individual became the head of government (president of the council of ministers or prime minister), with Charles Maurice De Talleyrand-Perigord being the first president of the Council of Ministers under the Bourbon Monarchy in 1815. The transition to a more stable form of republican democratic government only occurred with the Third Republic (Hanson Reference Hanson2010), which lasted 70 years from 1870 until the Nazi German occupation in 1940. The prime minister was the chief executive under the Third and Fourth Republics. Since the transition to a semi-presidential system with the Fifth Republic in 1958, the prime minister and the popularly elected president share executive power. When we examine the prime ministers and presidents since 1815, we find five prime ministers of Protestant religious background, one of which also served as a president in the Third Republic, four prime ministers of Jewish religious background, and one prime minister of Orthodox Christian background in the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Republics (Table 3).

In sum, France had ten chief executives of a non-Catholic religious background, much larger than was the case in Britain, where there has been only one chief executive affiliated with a non-Protestant religion. Seven out of ten French chief executives of non-Catholic affiliation have been leftists, mostly radicals and socialists, and two recent non-Catholic prime ministers have been from the centrist political party, Renaissance, led by Emmanuel Macron. Only one out of ten French prime ministers of non-Catholic backgrounds was affiliated with a conservative political party. Although France is the European country where the Muslim minority is the most underrepresented in the national legislature, with an average of 38 “missing” Muslim members of the parliament on average, the few Muslim-origin members of French parliaments have also been overwhelmingly from leftist parties (Aktürk and Katliarou Reference Aktürk and Katliarou2021). Thus, the path out of marginality for religious minorities in France historically passed through leftist, and often socialist, political parties.

The pattern of a mostly leftist path for the national leadership of religious minorities is explicable through the national-religious configuration of France. France combines a universalistic majority religion, Catholicism, with a constitutive conflict against adversaries of a different religion, Protestant England earlier and Protestant Prussia and Germany later (Marx Reference Marx2003; Colley Reference Colley2009; Sambanis et al. Reference Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth2015), followed by a violent anti-colonial war against a Muslim adversary, Algeria (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2013). More importantly, however, France had a very violent domestic constitutive conflict, the French Revolution and its aftermath, which split the polity ideologically between a leftist republican constituency and a conservative right-wing constituency (Hanson Reference Hanson2010; Berman Reference Berman2019). The battle or the struggle of “the two Frances” (for example, Lengyel Reference Lengyel1934; Johnson Reference Johnson1978) is indicative of a “nationhood cleavage,” which includes fundamental disagreements about the origins, the definition, and the membership of the national community among the two main political camps (Aktürk and Lika Reference Aktürk and Lika2022). In the struggle of “the two Frances,” the non-Catholic religious minorities constitute a key component of the leftist-republican camp in opposition to the conservative right-wing camp. Unlike in Britain, many leftist politicians of religious minority backgrounds became national chief executives in France. Nonetheless, religious minority politicians did not become nationalist or conservative political leaders in France, which is the third pattern observable in a few countries such as Hungary and Italy.

Causal Mechanisms of Religious Selection in the French Case

The main difference in causal mechanisms of religious selection in a polity characterized by a nationhood cleavage such as in France is that there are two opposed logics and politics of attributing disloyalty to the nation. While the conservative nationalist camp could attribute disloyalty to the religious minorities such as the Jews and/or the Protestants as fifth columns of a historical adversary, which is similar to the examples we observed in the British case, the secularist republican camp could attribute disloyalty to the religious majority as being enemies of the secular republican regimes and as a fifth column of the supranational papal-clerical actors, who constitute the other historical adversary. This is what one observes in iterations of the republican secularist versus conservative nationalist controversies that periodically erupted, the most infamous example of which was the Dreyfus Affair (for example, Birnbaum Reference Birnbaum2015, 18–31; Berman Reference Berman2019, 113–124). It may be argued that the republican-socialist conception of the French nation that crystallized at the turn of the 20th century can be traced to the “militant Dreyfusard circles” that included many French Jewish leftists including Leon Blum, Emile Durkheim, Lucien Levy-Bruhl, and Marcel Mauss (Birnbaum Reference Birnbaum2015, 56). In short, while the right was able to securitize religious minority politicians as potentially disloyal and subversive, the left was also able to securitize religious majority politicians as potentially disloyal and subversive. This allowed for the upward mobility of religious minorities to national leadership on the left, which is the major difference between the nationhood cleavage pattern from a sectarian hegemony.

Pattern of an Ecumenical Nationhood: Religious Minorities as Nationalists and “Fascists” in Hungary and Italy

In the third pattern, in polities where the constitutive conflict of nation-building was against a main adversary of the same religious sectarian tradition, religious sectarian minorities would have the best chance of becoming national chief executives and even assuming leadership of right-wing nationalist parties. Religious minorities would have even better chances of political leadership if the majority religious tradition is supranational in its organization and doctrine, such as Roman Catholicism or Sunni Islam. Since the main national adversary is also from the same supranationalist religious tradition, the religious minorities might even be perceived as potentially more nationalistic than the religious majority. Hungary and Italy exemplify this pattern as I discuss further below. Hungary and Italy, both Catholic-majority polities, fought against similarly Catholic adversaries such as the Habsburg Empire in both cases and also the Papal States in the case of Italy to establish their independent nation-states. In a strong confirmation of the theoretical predictions of my argument, then, Hungary had numerous Protestant national and nationalist leaders from the 17th century to the present, whereas Italy had at least one Jewish Prime Minister already in the early 20th century, decades before France, the only other Western polity to have a Jewish prime minister. Moreover, Jews were very much overrepresented in the national legislature of Italy after its founding in 1871 (Klein Reference Klein2018, 33). These patterns persist over decades and even centuries, suggesting that they may be conceptualized as historical legacies (Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006; Reference Wittenberg2015).

There have been multiple Protestant Hungarian nationalist leaders. Protestant Imre Thököly (1657–1705) was a major Hungarian nationalist leader and presumptive king, who fought against the Austrian Habsburgs for Hungarian liberties (Britannica Reference Britannica2021). More prominently, in the 19th century, Lajos Kossuth (1802–1894), a Lutheran, was the principal Hungarian nationalist who “led Hungary’s struggle for independence from Austria” and became the regent-president of Hungary during the revolutionary uprising against the Habsburgs in 1848–1849 (Macartney Reference Macartney2022). Miklos Horthy, the military dictator who governed Hungary from 1920 until 1944, the longest reigning nationalist conservative leader of Hungary in the 20th century, who is described as a “fascist” by many, was also a Protestant (Horthy Reference Horthy2000 [1957]). Finally, in postcommunist Hungary since 1989, the most powerful leader on the right wing of the political spectrum and the longest-serving prime minister (1998–2002 and 2010–present) has been Viktor Orban, who is a Calvinist Protestant. Moroever, Katalin Novak, the first female president of Hungary (2022–2024), was also a Protestant. In a stunning finding that confirms the predictions of my argument, perhaps the most famous Hungarian nationalist leaders of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, Kossuth, Horthy, and Orban, respectively, hailed from the Protestant religious minority.

Hungary also had a nationhood cleavage due to a failed communist revolution following World War I, and a successful communist takeover with Soviet military support following World War II. Symptomatic of a polity with a nationhood cleavage, two Jewish-origin communist political leaders, Bela Kun and Matyas Rakosi, became the national chief executives of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic after World War I and the Hungarian People’s Republic after World War II, respectively (Hanebrink Reference Paul2018, 16-17, 171-181). In short, national leadership of religious minorities can be observed in both right wing and left wing Hungarian politics, which is indicative of an ecumenical nationhood.

I argue that the nature of the constitutive conflict explains this curious pattern of Protestant nationalist leaders in Catholic-majority Hungary. Moreover, the persistence of political legacies is particularly puzzling in this case because at least “three features of Hungary make it the least likely place of all to find continuities” (Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006, 11). Furthermore, the continuing prominence of Protestant politicians leading the conservative-nationalist right wing is particularly puzzling because the “Roman Catholic church community proved far more resilient against the depredations of communism than the Reformed (Calvinist) church community” (Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006, 14). The constitutive conflicts of Hungarian nation-building have been against the Austrian Habsburgs, an adversary that was Roman Catholic, like the majority of Hungarians. Such a national-religious configuration is one where nationalism and the religious identity of the majority militate against each other.

Italy, which has been overwhelmingly Catholic, “was the first European country to have a Jew, Luigi Luzzati, serving twice as prime minister” (Segre, 227). Italy’s exceptional status as such is rarely recognized and the previous sentence is the only one referring to Luzzatti (the more common pronunciation of his last name) in Dan Segre’s (Reference Segre, Birnbaum and Katznelson1995) chapter on “The Emancipation of Jews in Italy.” Similarly, there is a single mention of Luzzatti in Shira Klein’s book on Italy’s Jews from Emancipation to Fascism, despite Luzzatti being the first Jewish prime minister in Europe: “Luigi Luzzatti, born in Venice to Jewish parents, served as Prime Minister in 1910-1911” (2018, 33). Moreover, according to some, Italy had another Jewish prime minister earlier, Alessandro Fortis in 1905 (Catalan and Facchini Reference Catalan and Facchini2015, I), but it is uncertain whether Fortis was Jewish. Luzzati alone is sufficient to make Italy the first European country with a Jewish chief executive historically, 25 years before Leon Blum became the French prime minister. Jews were also vastly overrepresented in Italian national legislature: “In 1871, the Italian Chamber of Deputies, an elected body, counted eleven Jewish members (out of a total of 508, amounting to 2 percent) and fifteen in 1874 (3 percent), at a time when Jews formed only one-tenth of a percent [0.1 percent] of the total Italian population” (Klein Reference Klein2018, 33). There is even more to the exceptional status of Italian Jews, which constitutes one of the main questions of Shira Klein’s book on Italian Jews: “why most Italian Jews in the interwar period supported Fascism” (Klein Reference Klein2018, 2). In short, Jews were significantly overrepresented in the Italian national legislature, and they produced the first Jewish prime minister anywhere in Europe, and many if not most Jews supported Fascism, three exceptional characteristics that demonstrate the “third path” out of marginality that a religious minority might have: the nationalist and even fascist path.

Italy was a Catholic-majority polity that fought against Catholic adversaries, namely, the Habsburg Empire, and even more dramatically, the Papal States, in the constitutive conflict that culminated in Italian unification as a nation-state in 1870. The tension between the religious identity of the majority and the new nationalist identity was more dramatic and direct in this case than in most other cases because “by explicitly forcing Italians to choose between religious and national loyalty, the Church hampered state- and nation-building in a particularly profound way in Italy” (Berman Reference Berman2019, 144). The fact that Italian nationalists had to directly fight the papacy, which was the final step of Italian unification that claimed Rome as the capital, is significant in this regard, as Italy became a nation-state despite sustained papal opposition until the very end (O’Malley Reference O’Malley2010, 241–252).

Radical Change in the Original National-Religious Configuration: The Rise of Catholic-origin Nationalist and Conservative Leaders in Germany

Historical legacies are not immutable, although they are path-dependent and thus extremely hard to change. I ask whether, how, and when change is possible in these historical patterns. I argue that “change” can happen through disastrous processes since it often requires a new and more traumatic constitutive conflict that replaces the original constitutive conflict. Religious sectarian identity associated with the national leadership may change later due to more recent mobilizations for total war or revolution along a different identity fault line. I explain such a radical change in a case of world-historical significance for studies of ethnicity and nationalism: the establishment (unification) of Germany as a Protestant-led nation-state in 1871, and its subsequent radical transformation led by primarily Catholic-origin ultra-nationalist leaders during the 1930s under National Socialism. My argument, based on the main enemy demonized in the constitutive nationalist conflict as the main explanatory variable for religious sectarian patterns in national leadership, convincingly explains the otherwise enigmatic and pattern-breaking change in the national political leadership of Germany with the rise of National Socialism and the Holocaust.

Germany presents a case that started out with a pattern similar to Britain and France, where a distinctive religious sectarian core was identified with nation-building, namely, Lutheran Protestants of Prussia. Furthermore, as in the case of Britain and France where Catholics and Protestants were persecuted, respectively (Marx Reference Marx2003), Protestant-led German nation-building was initially accompanied by a major state-orchestrated top-down campaign of persecution against the main religious minority, Catholics, in what is known as the Kulturkampf between 1872 and 1878. Imperial Germany (1871–1918) was a constitutional monarchy. All the German emperors, as well as six of the eight Chancellors who governed Germany for 40 of these 47 years, were Protestants (Table 4). Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst was the notable exception as a relatively long-lasting Catholic Chancellor, although his mother was Protestant. In short, the Protestant hegemony in the national leadership of Imperial Germany is unmistakable.

Table 4. Chancellors of Imperial Germany by Religious Affilation, 1871-1918

Imperial Germany lost World War I and was followed by the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), which had fifteen Chancellors in fifteen years, along with two presidents. The first president, Friedrich Ebert (1919–1925), although baptized as a Catholic, publicly renounced religion and was an avowed atheist politician, while the longer reigning second president, Paul von Hindenburg (1925–1934), was a Lutheran Protestant, and indeed a direct descendant of Martin Luther (Table 5).

Table 5. Presidents and Chancellors of the Weimar Republic, Germany, 1918-1933

The Nazi takeover in 1932–1933 under the leadership of Adolf Hitler radically changed the religious sectarian composition of the national leadership in Germany. Hitler was an Austrian-born Catholic-origin politician whose political party, the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP), had its origins and first failed attempt to takeover in Munich, Bavaria, the Catholic heartland of Germany. Not only Hitler, but many of the other Nazi leaders were also of Catholic origin and from South Germany, including Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, and Heinrich Himmler (Table 6). Given that Catholics made up only one-third of Germany’s population at the time, this finding indicates a very remarkable overrepresentation of Catholic-origin figures in Nazi leadership.

Table 6. Key Leaders of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazis) by Religion

Source: The list of “key leaders” of NSDAP (Burack Reference Burack2017, Deutshce Welle); biographical information from various sources.

It has been argued that “Hitler patterned the organization of his party and his Reich after the Roman Catholic church, which had impressed him so much as a young boy,” as Hitler modeled the Nazi paramilitary SS in emulation of the Jesuits, chose a modified form of the cross (hakenkreuz, Swastika) as the Nazi symbol, and launched a total war across Europe that he depicted as a “crusade” (Waite Reference Waite1971, 245–246). While the papacy excommunicated Catholics who became members of the communist parties, none of the Catholic-origin Nazi leaders, including Goebbels, Göring, Himmler, and Hitler, was ever excommunicated (Lewy Reference Lewy2000; Carroll Reference Carroll2001; Chamedes Reference Chamedes2019). Some may object to Hitler being coded as a Catholic just because of being of Catholic origin and despite being non-practicing. However, unlike Disraeli who converted to Anglican Protestantism despite his Jewish origins, Hitler did not convert to Protestantism, which he hypothetically could have done especially if he identified German nationalism with Protestantism. But instead, he remained Catholic and was never excommunicated by the pope, who publicly met and interacted with him as a legitimate political leader, and these facts have been interpreted as papal support for Nazism by many critics ever since (Lewy Reference Lewy2000; Carroll Reference Carroll2001; Chamedes Reference Chamedes2019).

Nazism, as a self-identified workers’ movement, sought to overturn the social hierarchies in Germany through a revolutionary and totalitarian transformation. This transformation would also unseat the historical political elite of German nation-building, Protestant northerners, including the Prussian landed nobility known as the Junkers, personified in the first Chancellor of Imperial Germany, Otto von Bismarck, who is associated with the persecution of Roman Catholicism in the Kulturkampf. As Nazis swept to power, Catholic southerners became more prominent relative to Protestant northerners at the peak of German nationalist political leadership (Table 6).

German nationalism did not become a Catholic-led movement with the rise of Nazism, but rather, German nationalism ceased to be a primarily Protestant-led movement, overcoming the deepest religious sectarian cleavage in German society until then. Relatedly, the more specifically religious and institutional relationship between the Catholic Church and the Nazi regime, which has been the topic of a heated scholarly debate for many decades (Lewy Reference Lewy2000 [1964]; Carroll Reference Carroll2001; Chamedes Reference Chamedes2019), is beyond the scope of my inquiry, since my claim is not about religious minority-origin national leaders’ relationship with institutional religion. German nationalism is a case of “path-breaking” in which the religious sectarian core of nationalism changed with the ascendance of the previously marginalized Catholics to positions of national leadership through an ultra-nationalist movement.

How and why was such a momentous change possible? The key independent variable of my argument, the nature of the constitutive conflict, provides the answer. Unlike most nation-states in the world, Germany had a second and more violent and transformative constitutive conflict, namely, the Second World War, which included the Holocaust and the genocide of Jews as a central element. This new constitutive conflict displaced the original constitutive conflict by mobilizing German nationalism under the banner of Aryan supremacy and Anti-Semitism. This very violent transformative process rendered the Catholic-Protestant divide secondary by seeking to unite all Christians against a racialized ethnoreligious archenemy, the Jews. The securitization and genocidal eradication of Jews under the leadership of a Catholic-heritage German nationalist leader, surrounded by many other Catholic-heritage German nationalists, desecuritized German Catholics, who were previously securitized as potentially disloyal and subversive during the Kulturkampf. German national-religious configuration changed through a greater constitutive conflict that demonized a different religious minority, the Jews. This new conflict overshadowed and replaced the original constitutive conflict that pitted Protestant-led Germany against Catholic France in the war of 1871 that established the German nation-state (Sambanis, Skaperdas, Wohlfort 2015) and continued with the persecution of Catholics during the Kulturkampf.

The Catholic-Protestant divide became irrelevant, starting with Nazism and continuing in postwar Germany, where national historiography and education centered on atonement for the crimes of Nazism, which also united Catholic-Protestant alike, making sectarian differences irrelevant for national leadership. Postwar West Germany had Catholic political leaders for 33 out of 49 years between 1949 and 1998, in part driven by the Catholic majority that resulted from the division of Germany during the Cold War, in contrast to Weimar Germany where Catholics were only one-third of the population. German reunification brought in Protestant-heritage former East German states, thus altering religious demography again, and all three post-reunification Chancellors have been Protestants (Table 7). In a strong confirmation of my main argument, a new constitutive conflict, the Second World War, including the Holocaust, altered the national-religious configuration of originally Protestant-dominant Germany by desecuritizing Catholics, who were previously securitized as a potential fifth column as the Kulturkampf demonstrated.

Table 7. Postwar Chancellors of Germany by Religious Affiliation

Does the Argument Travel beyond the Old Western European Nation-States? Overview of the Universe of Cases from Latin America to Eastern Europe and beyond

Is my argument limited to the nation-building processes of key Western European states briefly examined in this article or is it applicable to other nation-states beyond Western Europe? The time dimension is critical in defining the universe of cases for a meaningful comparison. In order to meaningfully capture the “time to first religious minority national chief executive,” I include the current nation-states that existed at least a hundred years ago (circa 1924, or the interwar era) in the universe of cases. This time frame allows for comparing a sufficient number of national chief executives (typically more than ten national chief executives in a century), which may be necessary for the rise of a religious minority chief executive from a demographic and statistical point of view. For example, if the largest religious minority is ten percent of the population (one in ten), and the nation-state only has eight national chief executives, it may be argued that there has not been a sufficient number of chief executives to observe a religious minority chief executive, even if the selection processes of the chief executive are free of any religious sectarian prejudice. I exclude states that are hereditary monarchies with no alternative executive claiming popular legitimacy. Thus, constitutional monarchies such as the UK, with a popularly legitimated chief executive (that is, the prime minister) are included, but hereditary monarchies without a popularly legitimated chief executive such as Andorra, Liechtenstein, and Saudi Arabia are excluded. Defined as such, the universe of cases includes 22 American nation-states (Fitzgerald and Cook-Martin Reference FitzGerald and Cook-Martin2014) and 25 European nation-states,Footnote 1 which existed a hundred years ago (circa 1924). Beyond this Euro-American core, ten currently existing African and Asian polities were not colonized by European powers (Vogt 2019, 31) and were independent by 1924, and nine of these have national chief executives claiming popular legitimacy: Afghanistan, China, Ethiopia, Iran, Japan, Liberia, Nepal, Thailand, and Türkiye.Footnote 2 In sum, 56 current nation-states are included in the universe of cases, with the caveat that this is a generously large selection since it is debatable whether some of these polities that were independent as of 1924 existed for a hundred years (for example, Latvia) and it is debatable whether some of their national chief executives claimed popular legitimacy.

Among the universe of 56 nation-states, five of them have been discussed earlier as the primary case studies for heuristic purposes of theory building. Of the remaining 51 nation-states, one only would expect a small minority to have any national chief executives of religious minority background both for demographic reasons, and also because the constitutive conflicts of nation-building were fought along religious fault lines, fusing national and religious sectarian identity in numerous cases including Greece, Ireland, Poland, and Spain (Marx Reference Marx2003; Grzymala-Busse’s Reference Grzymala-Busse2015). Thus, national leaders of religious minority backgrounds are expected to be a rare exception rather than the norm. Although the universe of cases and the time period is vast, it is possible to identify the few cases of a national chief executive of a different world religion, such as a Jewish, Hindu, or Muslim national leader in a Christian-majority polity or a Christian national leader in a Buddhist-, Muslim-, or Shinto-majority polity. It is not possible, however, to review in detail all 51 nation-states’ chief executives over 100 years (5,000 country-years) for their “religious sectarian” (for example, Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant) biographical details within the constraints of this article.

Forty eight of the 56 countries independent since 1924, an overwhelming majority, are Christian-majority polities, including all the American nation-states, all the European nation-states except for Albania, and both African nation-states, namely, Ethiopia and Liberia. Among this large pool, the Catholic-majority Latin American nation-states that mobilized against Catholic Spain in a constitutive conflict would be more likely to follow the pattern of ecumenical nationhood with the most potential for a religious minority national leader. However, an important limitation must be taken into account: Iberian colonialism so thoroughly converted the Americas to Catholic Christianity that only in three Latin American countries a non-Christian minority exceeds one percent of the population: Jews in Argentina and Muslims in Guyana and Suriname. With such an extraordinarily homogenous religious demography, it is also least likely for there to be a non-Christian national chief executive in Latin America. For the same demographic reason, however, the appearance of a national chief executive from a non-Christian religion in Latin America would be a strong confirmation of my argument’s predictions given the nature of Latin American constitutive conflicts. Indeed, four Latin American states had Jewish national chief executives according to the Jewish periodical, Forward (Fisher Reference Fisher2019): Peru (Efrain Goldenberg; Pedro Pablo Kuczynksi; Yehude Simon; Salomon Lerner Ghitis), Guyana (Janet Jagan), Panama (Max Delvalle and Eric Delvalle), and the Dominican Republic, which very briefly had a Jewish president (Francisco Henriquez y Carvajal) before the US occupation.Footnote 3 In 2024, Mexico became the fifth Latin American country to have aJewish chief executive with the election of Claudia Sheinbaum as its first Jewish president (Acevedo, Conde, andLinares Reference Acevedo, Conde and Linares2024). When we turn to Christian-majority polities outside of Latin America, apart from France and Italy already discussed, only Latvia during the interwar era (Zigfrids Anna Meierovics) and Czechia (Jan Fischer) had prime ministers whose fathers were Jewish, and Jan Fischer self-identifies as Jewish (Fisher Reference Fisher2019). Czechia’s constitutive conflict for independence is similar to Hungary in that Czechia as a Catholic-majority polity with a sizeable Protestant and Jewish minority struggled against the Catholic Austrian Habsburgs and successfully achieved independent statehood with the breakup of the Habsburg Empire in 1918.

There were only four independent Muslim-majority nation-states as of 1924: Afghanistan, Albania, Iran, and Turkey. Iran provides a clear case of religious sectarian national-religious configuration where a Shiite polity has been in constitutive conflicts against Sunni Muslim polities since the early 16th century, along with non-Muslim (that is, British and Russian) imperial powers in the 20th century. Afghanistan and Turkey are cases of Muslim mobilization (though not only Sunni) against Christian adversaries (British, Russian, etc.) in their constitutive conflicts of nation-building. As my argument would predict, Iran did not have any non-Shiite national leaders, while Afghanistan and Turkey did not have any non-Muslim national leaders. But Sunni-majority Albania mobilized against a similarly Sunni Muslim Ottoman Empire (Doja Reference Doja2022), and in a stunning confirmation of my argument’s predictions, non-Sunni (Bektashi) Muslim and Christian leaders together have constituted a large majority of Albania’s national chief executives since independence. From its independence in 1912 until the Italian invasion in 1939, Albania had seven Bektashi (non-Sunni) Muslim, four Orthodox Christian, and four Sunni Muslim Prime Ministers (Bozkuş Reference Bozkuş2023, page 63, Table 2.5). Albania’s longest reigning totalitarian communist dictator, Enver Hoxha, likewise hailed “from a Bektashi Muslim Tosk family” (Bozkuş Reference Bozkuş2023, 65). Perhaps equally stunningly, among the eight Prime Ministers of Sunni-majority post-communist Albania, only one has been Sunni Muslim (Sali Berisha), whereas four have been Orthodox Christians, two have been Bektashis, and one has been Catholic Christian (Bozkuş Reference Bozkuş2023, 72, Table 2.6).