I am grateful to Zeynep and Harris for their careful reading of the book and their criticisms and suggestions. Often during book talks and debates, the author wishes to have received the reactions before producing the final version of the book. This is certainly the case here. In what follows, I will respond to those points that allow me to offer some additional empirical analysis or fill in the gaps left in the argumentative edifice of the book. I have grouped them together as they do overlap to no small degree.

Further Specifying the Argument

The first question raised by the commentators is how to understand the relationship between the three main factors that explain nation-building: effective public goods provision by the state, linguistic homogeneity, and of the spread of voluntary organizations. I see these factors as additive (in line with the statistical models) and their relationship therefore as substitutional. A very high capacity to deliver public goods (as in Botswana) can compensate for an anemic civil society. Very well-developed networks of civil society (as in Switzerland) can compensate for linguistic diversity, and so forth. This is not “a contradiction,” as Harris has it, but a simple relationship of substitution. Sequencing may matter as well, however: when the Soviet Union started to provide massive amounts of public goods, the political landscape had already fragmented along linguistic divides during the crucial transition from empire to nation-state, with lasting consequences. The very best outcomes would be expected, obviously, if all three factors work together, in the right direction, and early on. Indeed, a state like France would score high on all these three variables in the 19th century and we would expect an inclusionary power configuration—my definition of nation-building—to emerge.

Similarly, Zeynep asks how the two aspects of civil society development relate to each other. The first aspect is again a matter of historical sequencing: do voluntary organizations emerge before the transition to the modern nation-state, thus shaping the power configurations that emerge after that transition? The second aspect relates to the depth of this development: how far have voluntary associations evenly spread across the population of a country? Again, it may very well be that there is path dependency and that later depth therefore cannot compensate for the lack of early appearance. But I do not have the empirical means to test this argument, and the comparison between Belgium and Switzerland doesn’t allow me to explore this issue either.

Zeynep also asks what explains differences in civil society developments across countries. On pages 47 and 48 of Nation Building, I detail the factors behind the early and even spread of civil society organizations in Switzerland compared to Belgium: 1) the political fragmentation of Switzerland was mirrored by its religious heterogeneity, and the competition between Catholic and Protestant churches led to high literacy rates; 2) the political fragmentation of Switzerland, compared to autocratically ruled and often foreign dominated Belgium, also made it more difficult to suppress early civil society organizations; and 3) industrialization was more evenly distributed over the different Cantons in Switzerland compared to Belgium. These are historically specific factors, however, and I am not sure one could generalize them to other cases. This is one of the reasons that the civil society factor is not endogenized in the theory offered in the book. I agree with Zeynep that to do so would be a fruitful avenue for future research.

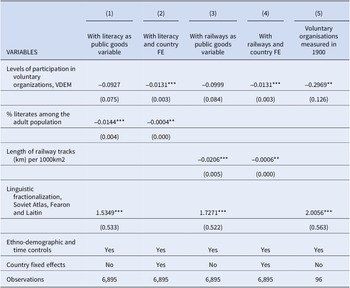

In this context, Zeynep also helpfully suggest that I use, in the quantitative analysis, another indicator of civil society development available in the VDM dataset (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Steven Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Luhrmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Alizada, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Hindle, Ilchenko, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, von Römer, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2020). I followed up on this suggestion and present the results in Table 1, which reproduces some of the core statistical models of the book (Tables 5.3A and 5.3B), replacing the count of voluntary organizations that I had used, available from 1970 onward only, with the new variable that has observations for the decades before the 1970s as well.

Table 1. Robustness check with another measurement of civil society development: GLM models of the share of the excluded population

Robust standard errors in parentheses; Constant not shown *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

The data codes whether citizens join voluntary organizations that are run independent of the state (unlike in the Communist Youth Leagues, for example), and how widespread participation in such organizations is. It is unclear to me how coders can determine this for example for Mexico in 1789 (when the data series start) or in Laos in 1970. The data are therefore much less precise than the number of voluntary organizations that I had used in the book, which is based on a global compilation of such organizations. The results are mixed. In standard times-series cross-sectional regressions (Model 1 and 3), the variable doesn’t reach standard levels of significance, even though the sign of the coefficient points in the right direction. It does, however, perform well in country fixed effect models (Model 2 and 4), which are arguably more precise as they rely exclusively on changes within countries over time. Coders are probably more accurately capturing these changes than differences between countries. The results are unequivocal: The more citizens join voluntary organizations, the more inclusionary the power configuration in a country, in line with the argument of the book.

Alternative Routes to Nation-Building I: Violence and Forced Assimilation

Perhaps the most important point raised by both Harris and Zeynep concerns the role of violence in nation-building and I will show empirically that violence is not an alternative route to nation-building that the book should have considered. But we first have to clarify our understanding of nation-building. The book defines it as political integration across ethnic divides or, more precisely, as an inclusionary ruling coalition comprising majorities and minorities alike. It is not to be confused, as the introduction of the book makes explicit, with ethnic homogeneity.

In contrast, Harris seems to think that at least in regimes where ethnic nationalism reigns, successful nation-building means, in the eyes of political elites, that “the boundaries of the nation [are] congruent to the boundaries of the state.” War and violence can bring about such congruence, by expelling minorities violently, conquering territory inhabited by co-nationals, and so forth. The Balkan wars might be the prototype of how to successfully build a nation if we define nation-building, following the perspective of ethnic nationalists, as ethnic homogenization. So, is it a matter of terminology whether or not violence leads to nation-building? Not quite, since ethnic homogenization might also make it easier to politically integrate minorities as it reduces the size of the minority that needs to be politically integrated. Below, I will therefore assess separately whether violence leads to the political integration of minorities (my understanding of nation-building) and/or to ethnic homogeneity (Harris’ understanding of nation-building).

A second issue concerns forced assimilation, which can also lead to ethnic homogeneity, as discussed by Zeynep. Forced assimilation does not change the population composition of a state, unlike violence, but it shifts the boundaries of the ethnic divide within that population over time. As Zeynep reminds us, policies of assimilation can at times be heavy-handed, leaving her to wonder if cases of forced assimilation (such as currently directed at the Uighurs of China) should count as routes to “successful” nation-building. In response, I will restate some arguments and examples from the book.

Third and relatedly, Harris offers an additional argument as to which countries are more likely to pursue such strategies of forced assimilation. Based on his previous work on the Ottoman domains and his joint work with Keith Darden (Darden and Mylonas Reference Darden and Mylonas2016), he expects that violent assimilation strategies will be pursued by a state surrounded by competing, revisionist states that threaten its territorial integrity, seek to overthrow its government, or try to force a specific minority policy upon it. In other words, the international environment, which my book intentionally neglected, could play an important causal role in explaining nation-building strategies and outcomes.

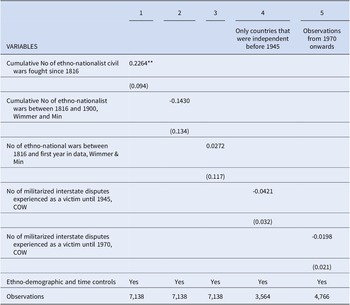

Let me address these issues one by one. First, is war and violence a route to successful political integration, using my definition of nation-building to start with? Table 2 reproduces some statistical models from the book (Model 1 in Table 5.1) and adds some new ones. The outcome is the same as in chapter 5 of the book: the population share of ethnic groups that are not represented in national government, or the share of the excluded population for short. The higher this share, the less “successful” nation-building. Model 1 shows that the cumulative number of ethnonationalist civil wars, which counts how many anti-colonial wars of independence and how many post-independence ethnic civil wars were fought since 1816, is indeed negatively associated with the share of the excluded population after the Second World War. However, this association might very well be due to reverse causation as high levels of exclusion will lead to more ethnic wars (as shown in Wimmer et al. Reference Wimmer, Cederman and Min2009). In Model 2, I therefore restrict the count of ethnonationalist wars to years before 1900 and in Model 3 to the period before the measurements of ethno-political exclusion set in (1946 for older states or the year of independence for younger ones). Models 2 and 3 show that violence is not a viable route to nation-building, understood as political inclusion.

Table 2. Violence as a strategy of nation-building? GLM models of the share of the excluded population

Robust standard errors in parentheses; Constant not shown *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Next, I evaluate whether a hostile international environment leads to forced assimilation and thus, overall, to a lower share of the excluded population, as more and more politically marginalized minorities cease to identify as such and “pass” as majority members. To measure whether the international environment encourages forced assimilation policies, I rely on the Militarized Interstate Dispute dataset (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, D'Orazio, Kenwick and McManus2020). I count the number of disputes in which the focal country was not the instigator and did not make revisionist claims on the adversary. I further focus on cases where the dispute involved at least the display of military force (e.g. amassing troops at the border). Again, I generated two versions of the count variable. The first one starts in 1816 and stops in 1945 (Model 4 in Table 2). It only includes countries that were independent before 1945 and thus are able to look back on a history of interstate disputes. The other measurement (Model 5 in Table 2) stops in 1970 after many more countries became independent and thus candidates for such disputes. This model only includes observations after 1970, again to avoid endogeneity problems. The results of both models are again not favorable to the argument.

All models in Table 2 use my definition of nation-building as the outcome to be explained. What, however, if we shift to Harris’ understanding and define nation-building as ethnic homogenization, thus adopting the view of ethnic nationalists? Could ethnonationalist wars and violence or a hostile international environment lead to more linguistically homogenous countries, either through ethnic cleansing or through forced assimilation, thus indirectly helping the task of political integration (or nation-building in my understanding)? Table 3 gives the answers, using the same war and conflict variables as before but linguistic fractionalization, measured in the 1960s, as the outcome. The results again do not support a bellicose theory of nation-building, except in Model 2. This model refers to the number of ethnonationalist wars between 1816 and 1900 and captures mostly the ethnic civil wars and violent independence struggles of 19th century Europe. They may indeed have had the effect that Harris, who happens to be an expert in European nation-building before World War I, suggests. The story does not seem to travel to other time periods and regions, however, as Models 1, 3, and 4 demonstrate.

Table 3. Do war and violence produce ethnic homogeneity? Cross-sectional GLM models of linguistic fractionalization

Robust standard errors in parentheses; Constant not shown *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Finally, I would like to address the issue of forced assimilation raised by Zeynep. It is explicitly discussed in the chapter on Botswana, whose government has pursued a strong-handed policy of linguistic and ethnic assimilation since independence. As I show in that chapter, it has been “successful” from a homogenization point of view: the share of non-Tswana has been steadily reduced over time through identity shifts by minority members, giving rise to the short-hand description of Botswana as “Africa’s France.” As I discuss in detail in this chapter, the assimilation policy was accompanied by political inclusion: in terms of cabinet seats and parliamentary representation, Botswana’s institution of power mirrors the ethnic composition of the population very well indeed.

Without such political inclusion, the forceful policy of assimilation would not have worked, but backfired. Ethnic minorities who do not “own” a proportional share of the state will resist identifying with it and refuse to assimilate into the dominant majority, even if encouraged by a strong-handed assimilation policy. They might pretend to identify as Turkish (or Han) when pressed to do so, but privately and within their families hold on to the idea of a separate Kurdish (or Muslim) identity and a political project of redress or revenge. Empirically, Chapter 6 leaves no doubt about this proposition: Members of politically discriminated against groups are far less identified with the nation than any other group. I highly doubt (but do not show in the book) that forced assimilation can work under such conditions. If this conjecture is correct, China’s Uighur population will never become Han, despite the policy of forced assimilation. Rwanda’s Hutus, ruled by a Tutsi minority, will not buy into the post-ethnic nationalism of the regime unless it goes hand in hand with actual power-sharing, which has not happened so far.

Incidentally, this allows me to address a related point raised by Zeynep. Can China really be counted as a case of successful nation-building, she asks, given the situation in the Northwestern province and in Tibet? To clarify, nation-building is not either a failure or a success, but a matter of degree. The record of a country can therefore be mixed depending on which groups or regions or periods we look at. The controlled comparison between extreme cases (Belgium and Switzerland, Russia and China, Somalia and Botswana) might have given the impression that my understanding of nation-building is dichotomous. Clearly, China’s integration of the various linguistic groups among the Han (who form over 90% of the population and count over a billion individuals) into a single political space should be counted as a remarkable success. The situation in Tibet and Xingjian clearly represent “failures” that a complete discussion of the case of China would have to explain. As I stated repeatedly in the book, the China chapter disregards the situation of the non-Han minorities and focuses on the much understudied and misunderstood case of nation-building among the Han.

Alternative Routes to Nation-Building II: Power-Sharing Enforced from the Outside

Harris raises a second, equally important issue related to the international environment, which the book explicitly and intentionally neglects. As he notes, it does not discuss the possibility that political inclusion across ethnic divides can be imposed on a country from the outside—independently of the domestic factors that the book emphasizes. In other words: Isn’t outside interference a route to successful nation-building as well—in contrast to the tenor of chapter 8, which argues that nation-building cannot be enhanced from the outside? Bosnia is a case in point: Isn’t the Dayton agreement and the power-sharing arrangement between Croat, Serbian, and Muslim segments of the population resulting in a highly inclusive configuration of power, similar to Switzerland?

In my view, Bosnia should not be seen as a case of successful nation-building because the power-sharing arrangement would quickly fall apart without outside enforcement. Moving beyond this counterfactual, we can test empirically whether power-sharing arrangements that are enforced from the outside lead, on average, to Bosnian style inclusivity—thus representing another road to nation-building that the book overlooks. In a footnote in Chapter 1, I reported such a test. It relied on a dataset on civil wars that came to an end through negotiation (Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003). Nine countries were governed, after their ethnic civil war ended, through power-sharing arrangements with third-party enforcement, broadly comparable to the Bosnian case (apart from Bosnia, the dataset lists Chad, Croatia, Lebanon, Liberia, Moldova, Rwanda, Tajikistan, and Zimbabwe). But the power configurations of these countries, as measured again through the share of the population not represented in national government, is indistinguishable from all other countries around the world. Enforced power-sharing therefore doesn’t lead, overall, to more inclusionary arrangements and Bosnia thus represents an exception.

Do the Intentions of National Leaders Matter? Revisiting the China-Russia Comparison

Both Zeynep and Harris raise questions about the comparison between China and Russia. To summarize, the book makes a Deutschean point in arguing that in China, the shared script allowed elites from all over the country, who spoke mutually unintelligible languages, to communicate with each other in writing and form political alliances with each other. In Russia, the communicative landscape was much more fragmented as the different languages were also written in different scripts, including Arabic, Cyrillic, Latin, Georgian, etc. This difference helps to explain why political alliances clustered along linguistic divides in Russia but not in China, paving the way for more inclusive ruling coalitions in China.

Harris argues again, similar to his point about nation-building as ethnic homogenization, that leaders’ intentions could matter more than the specificities of the communicative landscape. In the Soviet Union, he claims, nation-building was never attempted at the level of the country as a whole, but nations were built within the constituent republics, leading to the eventual break-down of the Soviet Union along these political boundaries. To clarify, my theory of nation-building is not about the intentions of central governments, but about whether historical processes foster the emergence of trans-ethnic political alliances among political elites. Nation-building, in other words, can proceed behind the back of the main actors, as it were. Whether or not it is the strategic goal of governing elites is therefore of secondary importance, according to my argument. Nation-building certainly was not the goal of elites in China and Switzerland, as detailed in the book, while it represented the main political project of Siad Barre in Somalia. And yet, Switzerland and Han China came together politically, while Somalia fell apart at the end of Barre’s rule. As I argue in the final chapter of Nation Building, intentions of ruling elites might matter at the margin—as the example of Nyerere in Tanzania shows (Miguel Reference Miguel2004)—but they do not represent a main driving force.

This line of reasoning might, of course, be empirically wrong. But a closer look at the strategic intentions of subsequent Chinese and Russian governments supports the view that leaders’ intention matter only at the margin.Footnote 1 In Russia, the Tsarist regime very much aimed at nation-building during the last decades of its rule. The Russification policy was supposed to stem the rising tide of minority nationalisms by fostering “national” cohesion among all Christian subjects, the vast majority of the population of the empire. The use of non-Russian languages in primary school was outlawed and the influence of the Catholic clergy or non-Russian Orthodox churches drastically limited. The policy lasted from 1863 (the second Polish uprising) all the way to 1905 (the first Duma election).

The Qing emperors pursued no such policy during the last decades of their rule. They were not even familiar with the idea of the “nation,” which was introduced by their republican opponents, and never attempted to eradicate non-Mandarin languages. To be sure, in the early 18th century a Qing emperor tried to make Mandarin classes mandatory for all government officials (the equivalent of a Russification policy), but the policy soon lost its steam and was forgotten by the early 19th century. If nation-building succeeded in post-imperial China despite the lack of a corresponding imperial policy, and if it failed in Russia even though the Tsars very much aimed for it, then the intentions of ruling elites cannot represent a crucial factor.

But, what about the post-imperial period? True enough, as Harris points out, in the Soviet Union nation-building policies were pursued at the level of the constituent republics—precisely because the political arena had already fragmented along linguistic divides during the late imperial period and the empire had to be re-conquered by the red armies after the civil war. But, taming the nationalist spirits through the nationalities policy was only one side of the coin. On the other side, the regime fervently tried to instil Soviet patriotism in its citizenry—not under the term “nation,” to be sure, but referring instead to the “peoples of the Soviet Union”—in order to generate a civic national identity superimposed on the ethnic nationalities of the republics. In other words, the Soviets tried to build a multi-ethnic nation, similar to India or Switzerland. Under Khrushchev all the way to the Brezhnev era, the Soviet leadership even shifted back to an assimilationist strategy and tried to Russify the various minorities—again without much success. In short, the Soviet Union did attempt to build a coherent nation, first in a multi-cultural version and then in a straightforward assimilationist way. The unintended consequence of the nationalities policy, however, was that political alliance networks remained fragmented along linguistic divides and that the power structure, therefore, remained heavily tilted in favour of Russian speakers, as detailed in the book. Meanwhile, a multi-lingual coalition controlled China’s communist party from the beginning, similar to the Kuomintang party and the imperial governments before that.

The second point raised by both Zeynep and Harris is whether the communication mechanism operates at the level of elites or the masses. This is an important issue that the book does not clarify enough. The answer depends on which phase in the process of political development we are focusing on. Before the advent of mass politics, all that matters is communication among elites. After the political mobilisation of the masses for example through elections, these elites need to make claims that appeal to the general population as well. Language heterogeneity now matters both at the elite and the mass levels. In Russia, the transition to mass politics occurred sometimes during the late imperial period and definitively with the Duma elections of 1905. I show, focusing on the case of the Jewish political organisation Der Bund, that communicating in the language of the general population was crucial in order to gain a following and win votes. Political alliances thus fragmented even more as political movements started to exclusively cater to specific linguistic communities.

In China, the first elections were held after the end of empire and the transition to the modern nation-state. What languages the masses spoke and which script they used, therefore, did not matter much before the Kuomintang regime. Elites spoke a great deal of different languages but could communicate in writing in the shared classical script, which is equally distant from all vernaculars. This played an important role in creating multi-linguistic alliances before the transition to the nation-state. In turn, the multi-ethnic nature of political alliance networks helps to explain why China did not fall apart after the collapse of central imperial authority (not even during the warlord period). In other words, the vernacular languages spoken by the masses mattered more in Russia, due to the timing of elections during the transition from empire to nation-state, than in China, thus exacerbating the divisive role of Russia’s linguistic and scriptural heterogeneity.