Introduction

It is well acknowledged that M. K. Gandhi (Mohandās Karamcand Gāndhī, 1869–1948), one of the most prominent political leaders in colonial India, promoted the Hindu–Jain traditional notion of ahiṃsā in his native tongues of Gujarati and Hindi/Hindustani, rendering it “non-violence” in English, throughout the nationalist struggle in the subcontinent.Footnote 1 Gandhi labelled his anticolonial campaign satyāgraha (truth-force).Footnote 2 This term, originally invented by Gandhi during his twenty-one-year South African sojourn, denoted a philosophy as well as a method of mass agitation that prohibited use of violent means. After 1915, Gandhi consistently argued that the principle of ahiṃsā was the very foundation of “Indian” or “Hindu” culture and therefore his all-India satyāgraha campaign against the British Raj must be firmly rooted in it.

To the best of my knowledge, it has been almost accepted as a truism that Gandhi's idea of ahiṃsā/non-violence, the cardinal principle of satyāgraha, essentially originated from his childhood experiences (1869–88) in the Princely States of Porbandar and Rajkot, the western and the central regions of the Kāṭhiyāvād peninsula respectively, both infused with the religio-cultural ethos of ahiṃsā.Footnote 3 Yet such genealogical understandings of Gandhi's notion of ahiṃsā/non-violence credulously internalize his nationalist self-narrative, which was invented after he reached his late forties.Footnote 4 Although it is impossible to completely deny the psychological impressions of Gandhi's childhood, which are substantially subjective matters,Footnote 5 it is crucial for us to acknowledge that he almost never underscored the positive value of the term ahiṃsā in both public and private spheres until around 1915.

Rather than dwell upon the influences of his early life obtained from the “ancient” culture common in his homeland, in this article I will emphasize that Gandhi's experiences in South Africa (1893–1914) were vital. There, Gandhi led his satyāgraha campaign (1906–14) for the first time and peacefully combated racial discrimination against Asian immigrants by cooperating with people of diverse religio-cultural backgrounds, including Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Jews. During these years, Gandhi was exposed to trans-religious as well as universalist ideas. His principle of satyāgraha was by no means articulated using the word ahiṃsā or “non-violence” (although he did claim to deny the use of “violence.”)Footnote 6 Instead, it was chiefly expressed using concepts that appeared in the works of Leo Tolstoy and the late medieval nirguṇ bakhti poets. Finding a deep conceptual commonality between the putative “West” and “East,” Gandhi cherished his cosmopolitan vision. It was only later that Gandhi, now a matured politician of forty-five, first began to explain, while emphasizing its Hindu religiosity, the central virtue of satyāgraha by using ahiṃsā (and the term “non-violence” four years later). Although Gandhian-like ethico-humanist interpretations of ahiṃsā became prevalent among both scholars and civil rights activists after India's independence, “Vedic” and “Brahmanical” conceptions of the term, featuring aspects such as a high-caste vegetarian diet and cow worship and entailing communal implications, were conspicuously common among Hindu nationalist reformers in the pre-Gandhian era.Footnote 7 Gandhi's decision to utilize the word ahiṃsā immediately after his return to India in 1915 indicates his important intellectual evolution as a nationalist leader of the subcontinent. It also points to his tactical need to secure moral–financial support from primarily well-to-do vānīyās, the dominant Jain/Hindu mercantile caste in Ahmedabad, in order to establish and run his satyāgraha āśram in Kocrab.Footnote 8 Finally, from 1919 onwards, Gandhi began to translate the term ahiṃsā into the English and religiously neutral word “non-violence” during the beginning stage of his all-India nationalist campaign. This lesser-known genealogy behind Gandhi's self-narrative of ahiṃsā/non-violence will eventually provide us with a crucial insight, allowing us to relocate Gandhian thought from the Indian–Hindu nationalist framework to a broader global cosmopolitan context.Footnote 9 The multifaceted process of how Gandhi, in an apparently almost ad hoc manner, began to use the English rendering “non-violence” for ahiṃsā during the all-India nationalist campaign will also explain how he struggled to gain popular support from Indian Muslims.

Before moving on to a genealogical analysis of Gandhi's concept of ahiṃsā/non-violence, I should note one essential reason for the lack of scholarship on this subject. An almost insurmountable amount of historical materials pertinent to the topic exist and require multilingual analysis. There are voluminous documents written by Gandhi primarily in three languages (Gujarati, Hindi, and English),Footnote 10 amounting to more than 100,000 published pages, including editors’ translations, compiled in the three versions of Gandhi's Collected Works. These are, namely, the eighty-two volumes of the Gujarati version of the Collected Works entitled Gāndhījīno Akṣardeh: Mahātmā Gāndhīnāṃ Lakhāṇo, Bhāṣaṇo, Patro Vagereno Saṅgrah (1967–92, hereafter GA); the ninety-seven volumes of the Hindi version entitled Sampūrṇ Gāndhī Vāṅgmay (1958–94, hereafter SGV); and the hundred volumes of the English version entitled The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (1956–94, hereafter CWMG).Footnote 11 Most previous works, barring a few exceptions,Footnote 12 have failed to examine when, where, or in what context the terms ahiṃsā and “non-violence” exactly appeared in Gandhi's writings.Footnote 13 To earnestly confront this absence in past scholarly works, this article will chronologically examine all the materials available in GA, SGV, and CWMG in order to demonstrate the terminological as well as conceptual genealogy of Gandhi's idea of ahiṃsā/non-violence.

Gandhi's initial uses of the terms of ahiṃsā and “non-violence”

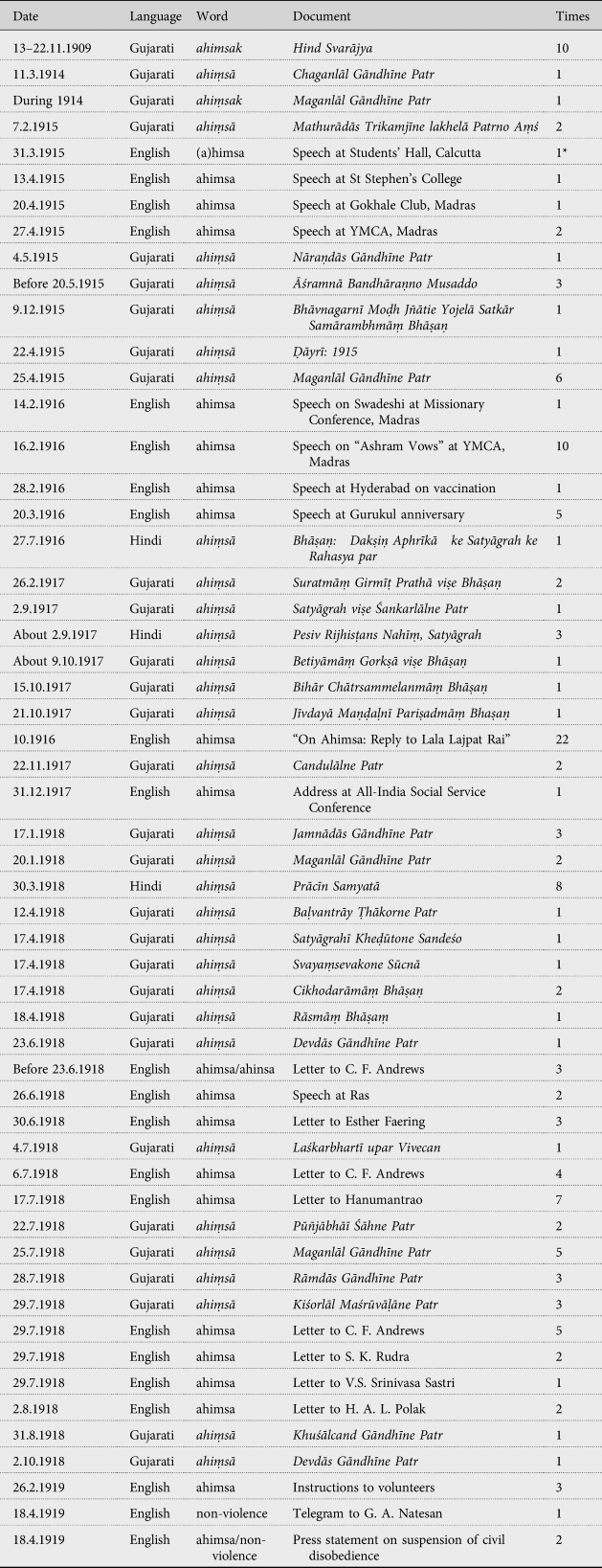

This section shows when, where, and how the words ahiṃsā and “non-violence” appeared in Gandhi's writings in the three languages; that is to say, Gujarati, Hindi, and English. According to GA, SGV, and CWMG, except ten references in Hind Svarāj written in 1909, the word ahiṃsā (or its adjective form ahiṃsak which also means “practitioner(s) of ahiṃsā”) appears only twice during Gandhi's South African period, both times written in Gujarati in his private letters (see Table 1 below, which lists the documents until 1919, the year when Gandhi first used the English word “non-violence”). As the table below shows, references to ahiṃsā in the Gujarati script (![]() ), the Hindi/Devanagari scripts (अिहंसा), and Roman letters (“ahimsa”) rapidly increased from 1915 onwards.

), the Hindi/Devanagari scripts (अिहंसा), and Roman letters (“ahimsa”) rapidly increased from 1915 onwards.

Table 1. References to ahiṃsā (![]() , अिहंसा) in GA and SGV, and ahimsa and “non-violence” in CWMG (1884–1919)

, अिहंसा) in GA and SGV, and ahimsa and “non-violence” in CWMG (1884–1919)

* Note. More precisely, in this speech Gandhi used the expression “abstention from himsa” instead of using the word “ahimsa.”

Additionally, as can be seen in Table 1, the English term “non-violence” was first used by Gandhi on 18 April 1919, the day on which he announced the temporary suspension of the first all-India satyāgraha campaign, known as the Rowlatt Satyāgraha or haḍtāl, due to the outbreak of a series of riots in north and western India.Footnote 14 From this day onwards, he began to use the word “non-violence” as an English rendering of ahiṃsā during the anticolonial nationalist struggles. According to H. Bodewitz, Gandhi's use of the term ahiṃsā as “policy of rejecting violent means” is a purely modern interpretation. “Non-injury” or “non-killing” rather than “non-violence” is a more common translation for the term ahiṃsā from a philological perspective. It should be noted that the word “non-violence” cannot be found in English dictionaries published before the Gandhian era.Footnote 15 It is possible to say Gandhi was the most influential, perchance the first, person to consciously coin the English term “non-violence,” and translated the Sanskrit word ahiṃsā into it.

Below, Gandhi's use of the word ahiṃsā/ahiṃsak in each document in his South African period will be explored, but first I would like to look at Gandhi's initial ten references to the term in Hind Svarāj. Hind Svarāj was Gandhi's first and only book to provide an exhaustive exposition of his understanding of the essence and philosophy of satyāgraha. Excluding the preface, the book contains twenty chapters. Along with the idea of satyāgraha, the book also deals with Gandhi's wide-ranging critical views on modern civilizations, colonial political economy, communalism, and national education in order to show why he considered satyāgraha the only true means to achieve Indian svarāj (home rule, self-rule).

What is most striking in terms of our ongoing discussion is that Gandhi never used the word ahiṃsā in Chapter 17, entitled “Satyāgraha: Ātmabaḷ,”Footnote 16 which is considered to be “the most important chapter in the whole book.”Footnote 17 In it Gandhi straightforwardly explains the core meaning and significance of satyāgraha and its contributing concepts (as further considered in the next section of this article). If the word ahiṃsā was not used in this chapter, where in Hind Svarāj did Gandhi deploy it? The word appears once towards the end of Chapter 9, “The Condition of India (Cont.): Train” (“Hindustānnī Daśā [Cālu]: Relveo”),Footnote 18 where he critically examines the modern scientific revolution (particularly the invention of the train) in England during the nineteenth century. After this, the word appears nine times in Chapter 10, “The Condition of India (Cont.): Hindus and Muslims (“Hindustānnī Daśā [Cālu]: Hindu-Muslmān”),Footnote 19 in the context of a discussion on Hindu–Muslim communal tension in India.Footnote 20

Let us see how exactly the word is used in these two chapters. Hind Svarāj is written as a supposed dialogue between a “reader” (a radical Indian revolutionary) and an “editor” (Gandhi himself) of the weekly journal Indian Opinion, which was published by Gandhi in South Africa.Footnote 21 While the former aims to achieve Indian svarāj by radical military means, the latter tries to persuade the former that violent methods are improper for achieving the “true” Indian svarāj. In the ending section of Chapter 9, there is a discussion about the communal conflict in India and the reader questions the editor as follows: “It is said that Hindus and Muslims have bitter enmity (hāḍver) … Hindus worship the cow, [and] Muslims kill (māre) her. [Therefore,] Hindus are ahiṃsak, [and] Muslims are hiṃsak [the adjective form of the term hiṃsā (killing, injury) which also means “practitioner(s) of hiṃsā”]. Thus, in every step, there are differences [between them], and how are these [problems] resolved and how can India become one [nation]?”Footnote 22 The editor answers, saying, “Thinking fundamentally, no one is ahiṃsak, because we [all] harm living beings (jīvnī hāni) … [If we] think ordinarily, many Hindus are meat-eaters (māṃsāhārī), therefore, they are not regarded as ahiṃsak … If such, it is completely odd [to say] that the one is hiṃsak and the other is ahiṃsak, therefore, they cannot be together.”Footnote 23 As can be seen here, Gandhi referred to the word ahiṃsak in relation to the Hindu customs of vegetarian diet and cow protection. He explained that these customs were generally acknowledged as the cause for the communal tension between Hindus and Muslims.

As a matter of fact, such communal debates revolving around the customs of Hindu vegetarianism and cow protection were prevalent particularly among the nineteenth-century Indian intellectuals associated with Arya Samaj. For instance, Dayānand Sarasvatī, a founder of Arya Samaj, wrote in his 1875 book Gokaruṇānidhi that cow protection was the essential tradition of Vedic Hinduism. Although Dayānand did not use the word ahiṃsā, he identified a Hindu as a rakṣak (protector) and a Muslim as a hiṃsak (killer) because of the latter's meat consumption when he elaborated upon Hindu–Muslim tensions.Footnote 24 A decade after the death of Dayānand, Arya Samaj split into two parties due to conflict between the members concerning the relevance of maintaining a vegetarian diet. Those members who held a secularist perspective in favor of meat-eating were acknowledged as the “cultured” or “college” party, whereas those against it were regarded as the mahātmā party, the special epithet given to revered saints or sages.Footnote 25 Gandhi's discussion of cow protection (gāynī rakṣā) in Hind Svarāj reflects the prevalence of this issue at the time.Footnote 26

In the other documents covered, as mentioned above, there were only two which included the word ahiṃsā in Gandhi's South African period. Both of these were Gujarati private letters written in 1914. These letters were addressed to Gandhi's uncle's grandsons, named Chaganlāl Gāndhī (hereafter Chaganlal) and Maganlāl Gāndhī (hereafter Maganlal). Chaganlal and Maganlal were residents of the Tolstoy Farm in South Africa and central members of Gandhi's satyāgraha campaign. The letter to Chaganlal written on 11 March 1914 reads, “Milk is believed to be a sacred thing [pavitra vastu], that should be taken; however, [it] should be regarded as unsacred [apavitra] … at least knowing this, [we should] forsake [it]. Such an idea that it is a pure flesh [śuddh māṃs] and against the duty of ahiṃsā [ahiṃsādharm] was never gone out of my mind.”Footnote 27 The letter to Maganlal written during 1914 reads, “From [my] experience, I came to know that as we have spent our life simply and have been firmly determined in our search for the awareness of the ātmā [ātmānubhūti], our desire [icchā] for eating many types of food will vanish away … Twenty years ago in London, too, I must have done so and I could have lived on an ahiṃsak diet [ahiṃsak khrāk].”Footnote 28 In these letters, Gandhi used the word ahiṃsā in relation to his daily diet for reducing desires. What should be noted here is that Gandhi, as can be seen in the letter to Chaganlal, viewed the habit of drinking milk as being as harmful as meat-eating. Such an idea was contrary to the general Hindu perception of milk as a sacred drink.Footnote 29 The discussions in both letters are focused on Gandhi's personal concerns; he never raised topics such as satyāgraha or other political issues in these missives, although his dietary or personal interests were intrinsically connected to his ideas of the body politic.Footnote 30

So far, we have seen how the term ahiṃsā was used in Hind Svarāj and two private letters. It is clear that a careful examination of Gandhi's South African writings reveals that he only used the word in relation to practicing vegetarianism or cow protection. It is highly significant that Gandhi never officially employed the term ahiṃsā to explain the virtues of satyāgraha in South Africa. Moreover, the letters cited above were both written during the last year of Gandhi's South African sojourn. This strongly indicates that throughout his twenty-one-year stay in South Africa, the concept of ahiṃsā did not occupy a central place in either his public or private experimentations (prayogo).

How did Gandhi explain the central principle of satyāgraha in South Africa?

The previous section demonstrated that Gandhi never used ahiṃsā/ahiṃsak in relation to satyāgraha during his South African period. If this was the case, then what words or concepts did he employ to promote his satyāgraha campaign?

The most crucial source for addressing this question is again Hind Svarāj. As has already been pointed out, Gandhi explained the meaning and significance of satyāgraha in Chapter 17 of the work. It begins with a question from the reader: “Do you have any historical evidence for satyāgraha or ātmabaḷ [the force of ātmā (soul, spirit, self)] that you are talking about? … It is still confirmed that without physical violence [mārphāḍ] an evildoer does not live righteously.” To answer this, the editor explains as follows:

A poet Tulsīdās jī sang as follows:

“Dayā [compassion, mercy, pity] is the root of dharam [the Avadhī equivalent of dharm(a)], Body (deh) is the root of pride (abhimān),

Tulsī [says], do not abandon dayā,

as long as [your] breath/life (prān [prāṇ]) is in [your] body/pot (ghaṭ)”

To me, this line seems to be a maxim (śāstravacan) … Dayābaḷ [the force of compassion], it is ātmabaḷ, and it is [also] satyāgraha. And, the evidence of this baḷ [force] is visible in every step.Footnote 31

Here, Gandhi quotes Tulsīdās's popular poem and explains the fundamental principle of satyāgraha using the concept of dayā.Footnote 32 Indeed, the word dayā was one of the central concepts employed to explain the ideological basis of Gandhi's satyāgraha in South Africa in both the Gujarati and Hindi languages.Footnote 33 Gandhi, more often than not, insisted that “dayā is the root of all religions” and emphasized the uttermost importance of the concept.Footnote 34 Other than dayā, Gandhi also used the word prem (love, affection, kindliness) or prembaḷ (the force of prem) as an alternative concept for dayā, dayābaḷ, and ātmabaḷ.Footnote 35 An analogous idea of dayā expressed in the lines quoted above can also be found in Mokṣamāḷā (1887), a book written by Jain ascetic Śrīmad Rājcandra that Gandhi read extensively during his South African sojourn.Footnote 36 Yet Gandhi never mentions the influence of Rājcandra or Jainism in Hind Svarāj.

As argued in the introduction to this article, Gandhi possessed a good command of three languages: Gujarati, Hindi, and English. Gandhi himself translated and published the English translation of Hind Svarāj under the title Indian Home Rule (1910) just after the publication of the original. This English translation is essential to understanding how Gandhi translated the Gujarati concepts of dayā and prem into English. He consistently replaced the words dayā and prem with the English word “love,”Footnote 37 and the terms ātmabaḷ and prembaḷ with “soul-force” and “love-force” respectively.Footnote 38

In the appendices of both Hind Svarāj Footnote 39 and Indian Home Rule,Footnote 40 Gandhi listed twenty books and essays which fundamentally impacted him before he wrote Hind Svarāj/Indian Home Rule. The first six works are all by Leo Tolstoy. The concepts of “love-force” and “soul-force” are, as far as Gandhi acknowledged, core principles in Tolstoy's writings.Footnote 41 En route to India in 1914, he explained the relationship between the essence of his South African satyāgraha campaign and Tolstoyan thought as follows:

[I] endeavoured to serve my countrymen and South Africa, a period covering the most critical stage that they will, perhaps, ever have to pass through. It marks the rise and growth of Passive Resistance,[Footnote 42] which has attracted world-wide attention … Its equivalent in the vernacular [i.e. satyāgraha], rendered into English, means Truth-Force. I think Tolstoy called it also Soul-Force or Love-Force, and so it is.Footnote 43

Among all Tolstoy's works, The Kingdom of God Is within You (1894) and “A Letter to a Hindoo” (1908) had a particularly significant impact in Gandhi's thought formation.Footnote 44 Gandhi later confessed that the former book became one of the three crucial sources that influenced his life most.Footnote 45

The fact that Gandhi directly corresponded with Tolstoy just before writing Hind Svarāj should not be disregarded.Footnote 46 From July to November 1909, Gandhi was staying in London as a member of the Indian delegation and lobbied for South Asian resident rights. In the imperial capital, Gandhi met young Hindu revolutionaries associated with the India House established by Śyāmjī Kṛṣṇa Varmā. Gandhi dismissively recognized those who resorted to revolutionary violence to fight against British colonialism as “anarchists” and “modernists.”Footnote 47 It is historically momentous that among these Hindu fundamentalist revolutionaries, Gandhi met V. D. Sāvarkar, who is widely believed to have persuaded Madanlāl Ḍhīṅgrā to murder Sir Curzon-Wyllie on 2 July 1909, just eight days prior to Gandhi's arrival in London.Footnote 48 Numerous public discussions among these revolutionaries seeking to justify Ḍhīṅgrā's assassination followed.Footnote 49 Gandhi was “both shocked and profoundly stirred” as he talked with these young Indians in London.Footnote 50 Simultaneously, Gandhi also read Tolstoy's “A Letter to a Hindoo,” which was printed in Free Hindustan, a political journal edited by Tāraknāth Dās, a prominent Indian intellectual residing in Canada. Gandhi was deeply impressed by Tolstoy's ideas of “non-resistance” (Tolstoy never used the word “non-violence”) and the “law of love.” Gandhi was convinced that his satyāgraha campaign should solely depend upon such Tolstoyan principles. After reading the essay, he immediately wrote a letter to Tolstoy, introducing his campaign in South Africa and asking Tolstoy for permission to translate the essay into Gujarati and publish it in Indian Opinion.Footnote 51 Then, while returning to South Africa from London on board the steamship RMS Kildonan Castle between 13 and 30 November 1909, Gandhi dashed off Hind Svarāj within ten days and also completed the Gujarati translation of “A Letter to a Hindoo.”Footnote 52 This series of events clearly shows how present Tolstoy's influence was in the writing of Hind Svarāj.Footnote 53

What is striking here is that Gandhi's understanding of both dayā and prem enjoys an intimate mutual translatability with the Tolstoyan idea of love, not only from a terminological view point, but also in terms of a deep conceptual affinity. During Gandhi's South African residence, Gandhi discovered, along with Tulsīdās, the importance of premodern (nirguṇ) bhaktism, whose nature was universally ethical, non-communal, egalitarian, and non-elitist.Footnote 54 He became particularly acquainted with the ideas of Kabair,Footnote 55 Narsiṃh Mahetā,Footnote 56 and Mīrābāī.Footnote 57 Various ideas associated with dayā or prem feature much more frequently in the writings of these poets than the principle of ahiṃsā.Footnote 58 Gandhi saw a conceptual commonality between the ideas of the premodern nirguṇ bhaktas and Tolstoy, in whose works anti-elitist, folkish/peasantry, and/or trans-religious dispositions were salient.Footnote 59

Besides, it should also be noted that the concepts of dayā and prem, which were rendered by Gandhi into the English terms “compassion/mercy/pity” and “love” respectively, were equally common in Christian, Islamicate, and Jewish cultures.Footnote 60 Gandhi's satyāgraha campaign in South Africa consisted of members of diverse religious backgrounds, including Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Most notably, wealthy Muslim merchants played a central role in Gandhi's satyāgraha campaign in South Africa.Footnote 61 Considering the nature and the socio-economico-cultural context of Gandhi's campaign undertaken in South Africa, the ubiquitous concepts of dayā/compassion and prem/love were fairly appropriate for his political agenda.Footnote 62 Contrarily, the concept of ahiṃsā, commonly understood as the “non-killing” of cows and practice of vegetarianism by Gandhi's contemporaries, was too specific in Hindu culture and barely possible to translate literally into Islamicate, Jewish, or Christian phraseologies.Footnote 63 It is difficult to find any plausible reason for Gandhi to use the word ahiṃsā in South Africa.

How did Gandhi invent his nationalist notion of “ahiṃsā” in India?

In this section, I will explore specifically how and why Gandhi added the “new” word of ahiṃsā to his previous cosmopolitan lexicon represented by dayā and prem after his return to India, and how and why the former eventually came to occupy a central place in his satyāgraha philosophy.

As shown in Table 1, Gandhi's first reference to the word ahiṃsā after his return to India in 1915 appears in a private Gujarati letter addressed to his relative Mathurādās Trikamjī, a son of Gandhi's sister. In this letter, written a month after his arrival, Gandhi wrote, “satya, brahmacarya, ahiṃsā, asteya, and aparigrah—observing [these] five yamas is mandatory for all spiritual aspirants [mumukṣu].”Footnote 64 Although his gradual interest in yamaniyamas in general was visible during his last few years in South Africa (including during his journey at sea),Footnote 65 this letter is the first document in which Gandhi refers to the specific content of each yama, including ahiṃsā.

The second reference to the idea of ahiṃsā after Gandhi's return can be found in his English speech at the Students’ Hall, College Square, in Calcutta, under the presidency of P. C. Lyons.Footnote 66 In this speech, Gandhi was reported to have spoken upon the principle of “abstention from himsa” as follows:

[H]e [Gandhi] must say that misguided zeal [among students] that resorted to dacoities and assassinations could not be productive of any good. These dacoities and assassinations were absolutely a foreign growth in India … The religion of this country, the Hindu religion, was abstention from himsa, that was to say, taking animal life. That was he believed, the guiding principle of all religions.Footnote 67

The context of the above speech was this. Shortly after his arrival in India, Gandhi was strictly keeping his promise to G. K. Gokhale; he promised to travel around the subcontinent for a year without engaging in any political action or speech, instead only acquiring firsthand knowledge of his homeland. During the initial phase of his travel, he encountered young enthusiastic students at College Square in Calcutta, whom he regarded as radical “anarchists” fired by the prevailing Hindu fundamentalist zeal. Gandhi was vastly apprehensive about this “misguided youth,” who believed that violent resistance to the Raj was a primal duty for them. Gandhi could not but deliver the above address, temporarily putting aside his promise to Gokhale in order to direct the students away from using such “nefarious means” incompatible with the essence of “Hindu religion.”

Promptly after this speech, Gandhi wrote a letter to Maganlal Gandhi in Gujarati, declaring that he “came to know in an extremely clear manner in Calcutta” that “the foundation of satyāgraha [satyāgrahano pāyo] is ahiṃsā.”Footnote 68 The letter demonstrates that the above speech in Calcutta was a transformative moment in Gandhi's intellectual evolution where he first developed a firm conviction that ahiṃsā was the cardinal precept of his religious politics. From this juncture onwards, Gandhi began to increasingly promote the concept of ahiṃsā, which had previously only been used by his contemporaries to denote the cultural habit of vegetarianism or cow worship, explaining it as the core of Hinduism, professedly the national religion. By so doing, he attempted to replace the rampant Hindu fundamentalist belief in revolutionary violence with his new pacifist interpretation of ahiṃsā.Footnote 69

Yet an additional point with regard to the above speech requires further consideration. As we have seen in the previous section, in one of his critical moments in London, Gandhi met young “anarchists” fueled by Hindu rebellious fervor. However, at that stage, in order to counter their arguments, Gandhi, while writing Hind Svarāj, promoted the universalist and egalitarian concepts of dayā and prem represented by Tolstoy or the late medieval nirguṇ bhaktas, which were considered to be equally translatable into various religious traditions. In contrast, when Gandhi encountered the students in Calcutta in 1915, inspired by Hindu fundamentalism, he advocated the notion of ahiṃsā, whose “Hindu” disposition was underlined. Indeed, after 1915, Gandhi began to insist that “ahiṃsā is the root of all religions.” This sentence exactly echoes his previous expression using the word dayā in South Africa: “dayā is the root of all religions.”Footnote 70 He further insisted that dayā was in fact merely a “limb/part [aṅg]” of the cardinal principle of ahiṃsā, emphasizing the latter's supreme position.Footnote 71 Why did Gandhi not continue to use the terms dayā and prem as the ultimate virtues of satyāgraha,Footnote 72 instead beginning to deploy the term ahiṃsā? In 1909, when he encountered analogous Hindu radicals, he still relied on the former terms to explain satyāgraha, not the word ahiṃsā.

In order to answer this question, it is essential to examine various entangled historical contexts. One reason for the terminological and conceptual shifts can be explained through Gandhi's growing awareness of a national language and religion. In January 1915, Gandhi reached Bombay from South Africa. Swiftly after his arrival, Gandhi, who had already earned his name as an acclaimed patriot,Footnote 73 obtained a number of invitations to speak at welcome meetings convened by various intellectuals, politicians, entrepreneurs, and religious leaders in the subcontinent.Footnote 74 One of the most important receptions was a garden party presided over by M. A. Jinnah, then the president of the Gurjar Sabha, in Bombay on 14 January 1915.Footnote 75 Once present, Gandhi was displeased to find that all the participants, including Jinnah himself, were giving their speeches solely in English. When his turn came, Gandhi, dressed in a traditional Kāṭhiyāvāḍī garment, daringly gave his speech in Gujarati and Hindi, insisting that the svarāj movement must be undertaken using their mother tongue(s) and be rooted in “Indian” culture.Footnote 76 It is intriguing to note that during Gandhi's South African years, he consistently wore the style of dress of an indentured laborer. Upon returning to India, he promptly amended this fashion, arraying himself instead in Kāṭhiyāvāḍī clothes that conveyed his willingness to represent the “beautiful manners and customs of India.”Footnote 77 Gandhi emphasized that it was essential to “proceed to our goal [of svarāj] in our own eastern ways and not by imitating the West, for we are of the East.”Footnote 78

Furthermore, Gandhi became perceptively aware of the fermenting spirit of the contemporary “Hindu” nationalism whose nature had been gradually communalized around the time of the Government of India Act of 1909.Footnote 79 The fact that Gandhi, with Svāmī Śraddhānand, an Arya Samaji sanyāsī, participated in the first All-India Conference of Hindus, in conjunction with the Kumbh Parva held in Haridwar in April 1915,Footnote 80 should not be underestimated.Footnote 81 At the conference, the Sarvadeśak Hindū Sabhā was established as a “ground front” with a “flourish of trumpets” to represent the Hindu community.Footnote 82 Although the conference at this stage was not as radically right-leaning as the later Hindu Mahasabha of the 1920s, it is still important to remember that Gandhi was “strongly supportive” of the formation of the Hindu Sabha, where “Hindu solidarity” in aid of national reforms such as Nagari and cow protection were officially promoted. Gandhi's recognition of the surging air of Hindu nationalism in India was arguably one of the key factors behind his promotion of the concept of ahiṃsā after 1915.Footnote 83 The purportedly “ancient” and ascetic precept of ahiṃsā presented the perfect vehicle for Gandhi to infuse his nationalist agenda with a stronger “Hindu” character, increasing the popularity of his project.

Finally, other than the growth of such nationalist sensitivities, Gandhi's moral–financial considerations should not be disregarded either. As Makrand Mehta, a renowned social and business historian of Gujarat, has accurately pointed out, “saintly Gandhi was also a man of practical wisdom—a tactician.”Footnote 84 Mehta has highlighted Gandhi's masterly synthesis of his personas as a “shrewd politician”Footnote 85 and a “homo religiosus.”Footnote 86 It is, in this respect, fairly inappropriate to apply the Weberian framework based upon the dichotomic hypothesis between “oriental spirituality” as “otherworldly” or “irrational” and modern economics as “this-worldly,” “practical,” or “secular” affairs.Footnote 87 Gandhi's idea of moral economy which was encapsulated in his use of the term “trusteeship” in his later years was by no means “otherworldly” nor “non-spiritual.”Footnote 88 Below, I would like to examine how Gandhi's financial concerns were intimately connected to his terminological/conceptual shift.

Before his return to India, Gandhi planned to establish a new communitarian settlement with approximately forty members, most of them previous inmates of the Phoenix Settlement and the Tolstoy Farm in South Africa.Footnote 89 Gandhi needed to carefully choose the most appropriate place to establish his settlement and secure financial backing to live together with his forty members. Having informed Gokhale of his plan around the time of his return to India, the latter had promised to provide Gandhi with all the necessary money from his India Servant Society.Footnote 90 Gandhi's feelings of joy and relief at this juncture were immense: “My heart swelled. I thought that I was released from the business [dhandho] of collecting money, so I became very happy [rājī], and now I would not have to live with those responsibilities.”Footnote 91 However, an unexpected incident occurred. Gokhale abruptly passed away during a fainting fit on 15 February 1915, only a month after extending his generous offer.

Gandhi began to look for a new patron. In his search, he considered locations such as Haridwar, Calcutta, and Rajkot before eventually deciding to establish his communitarian settlement in Ahmedabad.Footnote 92 He justified his choice on the ground that in Gujarat he would, being a Gujarati himself, “be able to make a full-fledged service to the country through Gujarati language.”Footnote 93 Yet, if this was his only reason, why did he not choose Rajkot or Porbandar, where he had actually grown up? Except for a short trip to take a matriculation examination during his boyhood, Gandhi had no experience of staying in Ahmedabad.Footnote 94 Indeed, as Riho Isaka has pointed out, these Princely States in Kāṭiyāvāḍ had a distinct linguo-cultural history apart from north Gujarat whose center was Ahmedabad.Footnote 95 Gandhi's core motive for choosing Ahmedabad was, as Gandhi wrote, that it was the “capital” of Gujarat and the center of commerce. He confessed that “there was a hope that wealthy people [dhanāḍhay loko] here will be able to give more monetary help [dhannī vadhāre madad].”Footnote 96

Indeed, Gandhi's first contact in his search for donations was Śeṭh Maṅgaḷdās Girdharlāl, a well-known Ahmedabad mill owner and a member of the Ambālāl family, the wealthiest and most successful Gujarati Jain plutocracy.Footnote 97 Gandhi sent him a detailed estimate of expenditure amounting to approximately six thousand rupees per year.Footnote 98 Other than Girdharlāl, Gandhi had also sought financial and moral support from businessmen and people like Govindrāo Āpājī Pāṭīl and Jīvaṇlal Varajlāl Desāī in Gujarāt Sabhā.Footnote 99

When considering the meaning and implication of Gandhi's need for financial backers, it is essential to bear in mind that his potential patrons were vāṇīyās who held an economically as well as politically dominant position in Ahmedabad. Additionally, these vāṇīyās, in tandem with brāhmaṇs in the area, were intimately linked with Vaiṣṇav Hindu cultural traditions, particularly Svāminārāyaṇ and Jainism, in which the principle of ahiṃsā was a central doctrine.Footnote 100 In this respect, Makrand Mehta has pointed out that by embracing the slogan of ahiṃsā, “Gandhi had cultivated cordial relations with Ahmedabad millowners, particularly the banias [vāṇīyās] belonging to his caste and sect.”Footnote 101

Yet Gandhi was not only keen to lean into the philosophical aspect of the Ahmedabadis’ religious doctrine; he was also highly flexible when it came to adapting religious ceremonies familiar to his supporters. For instance, according to Gandhi's Gujarati diary entry for 20 May 1915, just five days prior to the establishment of the āśram, he performed vāstu, a common ritual performed among Gujarati Hindus when they move to a newly built house.Footnote 102 In the ritual, a pot is filled with water and carried to the house by either an unmarried girl or a woman whose husband is alive. During the house construction, which requires digging operations, people believe that numerous insects are killed. Therefore they perform the ritual so that the gods will forgive their sin. Gandhi was flexible in the face of his new environment and willing to undertake religious ceremonies which, as Mehta wrote, “must have delighted all the Ahmedabad Hindus.” Therefore “Gandhi's strong commitment to Hinduism and ahimsa won for him the cooperation of the rich Hindu and Jain sections of Ahmedabad.”Footnote 103

However, his successful acts of assimilation do not mean that Gandhi was immune to the difficulties inherent in dealing with these donors, since they were, in some respects, very conservative, orthodox, and even communalistic.Footnote 104 Their strong prejudice, for instance, towards members of untouchable castes was apparent and explicitly incompatible with Gandhi's basic moral sensitivity. Gandhi thus had to defend the conceptual gap between his own humanist understanding of ahiṃsā and the prevalent cultural perceptions of it among Hindus and Jains in Gujarat.Footnote 105 There was a time of crisis just a few months after the establishment of the āśram when Gandhi completely lost his financial support due to his reception of untouchables into his āśram. Girdharlāl was inflamed by this incident, considering the āśram “polluted.” Since Gandhi did not want to change his attitude, he finally decided to leave the āśram and live in the untouchable colony in town. Yet, on the verge of shutting down the āśram, Gandhi was saved by an anonymous industrialist who was later revealed to be Ambālāl Sārābhāī.Footnote 106 Despite the fact that Gandhi's manifestation of varnaśram, one of his āśramvrat (vows of āśram), which indicates his incorporation of the four-varṇa system, was seen as the outcome of his compromising association with conservative Hindus/Jains,Footnote 107 Gandhi's firm belief in anti-untouchability never swayed throughout his life.Footnote 108

What, then, about his attitude towards Muslims? I think the most controvertible aspect when considering Gandhi's terminological/conceptual shift was that there was, compared to the terms of “compassion” (dayā) and “love” (prem), no shared common or fixed phraseologies for ahiṃsā among Urdu Muslims, despite the fact that there had been a rich and long tradition of Muslim–Hindu–Jain synthesis during the early Mughal dynasty.Footnote 109 Gandhi was well aware of this purported untranslatability, as I will discuss below.

Indeed, Gandhi was invariably very careful when he needed to choose a new key term for his political struggle. For instance, during his South African years, Gandhi gave both of his communitarian settlements English names, i.e. the Phoenix Settlement and the Tolstoy Farm respectively. While writing Hind Svarāj on the Kildonan Castle, Gandhi wrote a Gujarati letter to Maganlal on 24 November 1909, explaining the reason for utilizing English names as follows: “And even when giving a name, we will have to search for a common word [madhyasth śabd] in which a question of [the distinction between] Hindus [and] Muslims should not arise. Maṭh or āśram is perceived as particularly a Hindu word; therefore, they are not [to be] used, [but the name of] Phoenix is easily attainable, [and] a nice word. Since … it is neutral [taṭasth].”Footnote 110

Achyut Yagnik and Suchitra Sheth have aptly pointed out that when Gandhi named his new settlement in Ahmedabad āśram, he noticed a communal implication which potentially contradicted his view of religious neutrality.Footnote 111 The same deliberation can be applied to the term ahiṃsā, which also raised the communal issue. One of the feasible reasons for Gandhi to use the terms such as ahiṃsā, āśram, and varṇāśram in 1915 was the fundamental demographic situation in terms of religious population ratio in Gujarat, where Muslims played a much lesser role in Gandhi's satyāgraha campaign compared to that in South Africa.Footnote 112

What, then, were the consequences of Gandhi's terminological/conceptual shift in India? Although Gandhi, at first sight, skillfully employed the term ahiṃsā as the ideological basis of satyāgraha, contemporaneously serving both his nationalist sensitivities and his tactical financial concerns, the decision became almost untenable shortly after his political presence expanded beyond the linguo-cultural boundary of Gujarat. As Gandhi was, almost too rapidly, transformed into a national leader representing the two largest religio-political forces of the subcontinent, he became well aware that “it would be on the question of Hindu Muslim unity that my ahimsa would be put to its severest test.”Footnote 113

On the first day of the Rowlatt Satyāgraha campaign in Bombay on 6 April 1919, Gandhi held a huge mass meeting in the Sonapur Masjid compound where no less than five thousand Muslims gathered. Gandhi urged the audience to take “the vow of Hindu–Muslim unity” by embracing “a feeling of pure love” and “eternal friendship.”Footnote 114 It is notable here that he did not refer to the word ahiṃsā at this meeting. Following the outbreak of a series of riots in northern and western India, Gandhi immediately suspended the campaign and in a makeshift manner began to translate the word ahiṃsā into the English word “non-violence” (instead of “non-killing,” which might have recalled the communal debate on cow slaughter, as discussed above).Footnote 115 He then, reportedly, struggled to find equivalent phraseologies for ahiṃsā in Urdu as well as introducing his new method of mass boycotting of foreign cloth in his native tongues. Gandhi wrote, “I found that I could not bring home my meaning to purely Moslem audiences with the help of the Sanskrit equivalent for non-violence.”Footnote 116 However, he did not succeed in finding an appropriate alternative in Urdu.Footnote 117

During the Delhi Khilafat Conference in November 1919, the Gujarat Political Conference in August 1920, and the Calcutta Special Session of Congress in September 1920, Gandhi again never seemed to utter the word ahiṃsā (अिहंसा) (in Devanāgarī), ahiṃsā (![]() ) (in Gujarati), or ahimsa (in Roman italic letters) in either Hindi, Gujarati, or English speeches.Footnote 118 The editor of the Bombay Chronicle intriguingly recorded that at the Delhi Khilafat Conference, Gandhi spoke about his idea of “avoid[ing] injury of any kind” from “a secular point of view,”Footnote 119 seemingly evading the word ahiṃsā/ahimsa. At last, when Gandhi commenced the national boycott from August 1920, collaborating with the Kaliphat movement, he, though “being embarrassed of not obtaining an Urdu or Gujarati word,”Footnote 120 created the new English term “non-violent non-co-operation” for his campaign.Footnote 121 The Congress Constitution adopted at the Nagpur Session in December 1920, then, declared that “[t]he object of the Indian National Congress is the attainment of swaraj by the people of India by all legitimate and peaceful means.” Here, his religious terminology, that of satya and ahiṃsā, was obviously secularized.Footnote 122

) (in Gujarati), or ahimsa (in Roman italic letters) in either Hindi, Gujarati, or English speeches.Footnote 118 The editor of the Bombay Chronicle intriguingly recorded that at the Delhi Khilafat Conference, Gandhi spoke about his idea of “avoid[ing] injury of any kind” from “a secular point of view,”Footnote 119 seemingly evading the word ahiṃsā/ahimsa. At last, when Gandhi commenced the national boycott from August 1920, collaborating with the Kaliphat movement, he, though “being embarrassed of not obtaining an Urdu or Gujarati word,”Footnote 120 created the new English term “non-violent non-co-operation” for his campaign.Footnote 121 The Congress Constitution adopted at the Nagpur Session in December 1920, then, declared that “[t]he object of the Indian National Congress is the attainment of swaraj by the people of India by all legitimate and peaceful means.” Here, his religious terminology, that of satya and ahiṃsā, was obviously secularized.Footnote 122

Despite consistently insisting upon the importance of national religion and language, Gandhi, when faced with the questions surrounding the communal alliance between Hindus and Muslims, could not entirely avoid depending upon the English framework of the colonial master. In the end, such English renderings hardly conveyed the ethico-spiritual connotation of satyāgraha, which should have been starkly distinguished from the mere materialistic method of “passive resistance.”Footnote 123

Conclusion

In this article, I have chronologically examined Gandhi's writings in three languages and explored the genealogy of Gandhi's concept of ahiṃsā/non-violence, a cardinal precept of satyāgraha. By so doing, I have demonstrated four points. (1) The principle of Gandhi's satyāgraha campaign in South Africa was never associated with the “Hindu” notion of ahiṃsā. The idea of ahiṃsā was then considered to entail communal questions. (2) Gandhi's first satyāgraha campaign was chiefly promoted by the trans-religious, non-elitist, and egalitarian concepts of dayā/compassion and prem/love, as inherited from Tolstoy and the late medieval nirguṇ bhaktas. (3) The major reasons for Gandhi's deployment of the term ahiṃsā to explain “the foundation of satyāgraha” and “the religion of this country” or “the Hindu religion” after his return to India were intimately related to his awareness of the rising spirit of the contemporary Hindu nationalist movement and his tactical concerns for securing moral–financial support from local well-to-do vāṇīyās in Ahmedabad. (4) Gandhi first coined the term “non-violence” as a religiously “neutral” English rendering of ahiṃsā immediately after the suspension of the first nationwide satyāgraha campaign in 1919, due to his hasty recognition of the difficulty of using ahiṃsā alone.

The processes and reasons behind Gandhi's deployment of ahiṃsā/non-violence strongly indicate that Gandhi's emphasis on his childhood influences in the Princely States located in the western and central regions of Kāṭiyāvāḍ peninsula was a later retrospective interpretation. The extant historical documents demonstrate that he did not regard the positive value of the term ahiṃsā and by no means promoted it as a nationalist slogan before 1915. On the contrary, the cardinal principle of satyāgraha before India, which might be tentatively termed “proto-non-violence,” expressed with the terms dayā or prem, was invented while Gandhi was deftly cooperating with people from multicultural, multiethnic, multireligious, and multilinguistic backgrounds in order to fight against racial discrimination in South Africa. In this respect, Gandhi was, in Judith Brown's terms, undeniably a “critical outsider” of the subcontinent who primarily cherished his ideas as quite distinct from his nationalist contemporaries.Footnote 124

Finally, I believe that the historical findings in this article, which show the cosmopolitan genealogy behind Gandhi's nationalist self-narrative, allow us to gain an essential insight into David Hardiman's fundamental question proposed in his book Gandhi in His Time and Ours (2003): “why [do] Gandhi's ideas continue to resonate in the world today?”Footnote 125 Despite the lament that Gandhian thought has been largely obliterated in his home country,Footnote 126 it has left an indelible mark beyond the subcontinent, in Anglo-Saxon Protestant countries, South Africa, and Myanmar particularly.Footnote 127 Once the lesser-known global, though invariably peripheral or dissenting, genealogy of Gandhi's ahiṃsā/non-violence is unfolded, it comes as no surprise that the deep moral reverberations of his thought have reached people all across the world.Footnote 128

Acknowledgments

I must convey my deepest gratitude to the late Professor Haruka Yanagisawa who kindly supervised me at the beginning stage of this research in 2008. During the completion of this article, I was helped by many people and received various invaluable comments. I particularly would like to show my sincere gratitude to Professor Peter van der Veer, Professor Vinay Lal, Professor Akio Tanabe, and Professor Riho Isaka, as well as to the three reviewers of this manuscript, including Professor Ajay Skaria. I am also very thankful for Mr Anant Rathod, who always helped me find historical materials in Gujarat and verified subtle nuances in my Gujarati translations. If there is any error or inaccuracy in this article, all responsibility is solely my own.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244322000014.