Introduction

During the siege of the Calcutta fort in 1756, a complaint was made that Indian cooks were deserting their European masters—a complaint that might appear trivial in the context of a dire life-and-death situation. The flight of the cooks, one contemporary observer remarked, ‘left us to starve in the midst of plenty’.Footnote 1 Gripped by either fear or revenge, the ‘black militia’ consisting of servants, peons, and gun lascars recruited to perform quasi-military services allegedly deserted at the earliest opportunity. The labourers entrusted with the work of saving cotton bales and filling sandbags had also disappeared.

A year later, the victory at Plassey must have eased the pain and trauma of what had happened during the siege—the British empire's biggest scandal of the Black Hole tragedy—but the everyday inconveniences experienced by European masters vis-à-vis their domestic servants were far from over. In the next few decades, the English East India Company (EIC) remained occupied in stringing together ways of profitably managing trade and revenue, but domestic servants continued to pose a ‘problem’ both administratively and domestically. Unfortunately, we know very little about the ‘servant problem’ in early colonial India.

Thinking about servants requires us to ask two fundamental questions: who were they and what did domestic service mean? The identities of a servant as a contract wage earner or a person either belonging to a family as a member or tied to the family through fictive/constructed claims of kinship were not mutually exclusive. In other words, their identity existed in a continuum running from ‘free’ waged coolie on the one hand to ‘unfree’ slave on the other. The legal practices, of course, maintained boundaries of distinction, say between slaves and servants, but social conditions permitted permeability.Footnote 2 Not only natives, but also Europeans, kept slaves, as evidenced by their wills and public advertisements about their runaway slave-boys. The masters often suspected these boys of finding new jobs as servants.Footnote 3 Domestic service performed by both slaves and servants was therefore a form of employment as well as a type of relationship.Footnote 4 The label ‘servant’ concealed many other types of relationships within it, some overlapping and some seemingly contradictory.

Based upon a range of sources—judicial, visual, administrative, and, not least, personal—this article deals with the core issues outlined above in four different sections. The following section takes up examples from different types of sources to underscore the complexity of ascribing any ‘absolute’ meaning to the term ‘servant’. It argues that the terms were slippery even if the relationships embedded in them were obvious to the stakeholders (that is, the masters and servants). The second section charts a brief history of some of the terms related to domestic/menial service—primarily through naukars and chakars—and looks at the inner divisions along the axes of occupation, rank, work, gender, and caste. ‘Servant hierarchies’ drew from Mughal practices that were slowly recast under the regime of ‘new’ colonial masters and mistresses. This recasting has been traced in the third section of the article. While these three sections deal with the social relational identity of the servants, their chances and conditions of occupational mobility, and the reasons for their invisibilization, particularly of women servants, the last two sections of the article argue to treat them in their labouring capacity. By taking Calcutta as the case study, the article argues for the overlapping histories of coolies and servants, and thus questions the easy binary sketched between the public form of labour and the domestic nature of servitude. Through a close reading of regulations that the colonial state proposed for coolies and servants, the article argues that establishing a division between coolie and servants as labouring forms was an intrinsic part of colonial regulatory attempts.

The terms denoting either personhood or subjectivity such as ‘boys’, ‘girls’, ‘attendants’, ‘retinue’, ‘dependents’, and so on refer to the relationships of dependency and protection that existed in a variety of households. It can be argued that the individuals discussed below in the following section—Raddie and Ramdulal—were not distinctly servants. And this is precisely the crucial part of writing a history of servants: servant is a relational social identity structured through the relationships of domination and hierarchy. Munshis, banians, and clerks were ‘servants’ in the relational sense of the word. Their households had their own sets of domestic servants. The distinct system of classifying domestic servants on the basis of either free will or wage is difficult to identify. In the cases described below and many others, particularly those related to the slave–servant continuum, the lived reality was messier than normative distinctions would allow.Footnote 5 The nature of bondage, work, and caste was crucial in defining the menial identity, but the social identity of the servant displayed at least some fluidity in spite of such distinctions. Fluidity is not to be understood here as the freewheeling use of agency in shaping trajectories, but as conditions of change that modified the relationship of servitude. Violence and abuse, it must be reiterated, were part of this relationship. Therefore, the quintessential presence of a servant-like character, of a domestic-service/servitude-like relationship, and of the continuous potential to reconfigure that relationship through patronage and resistance is integral to servants’ past in colonial India.

Servants’ identity

In 1797, the case of a girl named Raddie (probably an anglicized corruption of Radha or Radhi) who had left her foster parents’ house was brought to the notice of the local British magistrate.Footnote 6 The contextual reading of witness accounts suggests that Mohun, her foster father, had a household of very modest means. The case in itself was about establishing the culpability of a certain daroga (native police official), Ramlochun Dutt, a 30-year-old man serving in southern Bihar, more than 300 kilometres from his native place in Bengal. Mohun had accused Dutt and his official assistant (a burkandaz) of forcefully detaining his adopted daughter and cohabiting with her. Running into several pages and based upon eight depositions, including Raddie's, the case illustrates the complexity of the social identify of the servant.

It is important to start with the direct stakeholders’ expressions of the nature of the relationship. Mohun claimed Raddie to be his adopted daughter—a young abandoned girl he had found under a peepal tree, probably at the age of three or four. Depositions suggest that, at the time of the trial, Raddie was somewhere between 15 and 18. Raddie, on the other hand, simply stated that, since her childhood, she had been under the protection of Mohun. Knowing the nature of the relationship was crucial for the magistrate. Through the replies to his probing and leading questions on the matter, we enter into the muddled complexity of Raddie's social identity as perceived by witnesses who were Mohun's neighbours, acquaintances, and, most likely, close friends. It is important to heed the witnesses’ accounts, because Raddie's social identity was not limited only to the direct claims made by her or Mohun, but also depended on how others perceived and defined the relationship.

The range of relationships described by witnesses suggested that she might be an inferior second wife, a mistress, a slave, a servant, a girl under ‘protection’, and, not least, an adopted daughter. We do not get a sense of whether Raddie earned any wage in the household—most probably not, although the immediate reason she ran off was a dispute between her and Mohun's wife on the issue of provisions that included clothes and rice. During the two-month period that elapsed between Raddie's running away and her deposition, she worked as a servant in two different households. She was given food and clothes by her masters. For a young teenage girl, who could well be lusted after by a 30-year-old daroga or by her male masters, such provisions in exchange of sexual liaison could have comprised her ‘wage’. If the term ‘servant’ masked the nature of the relationship, then ‘protection’ could very well conceal the meaning and form of payment, obligation, dependency, and (sexual) coercion.Footnote 7

If Raddie was indeed a slave–servant in Mohun's household, then the fused ideas of property and protection would have been the basis of Mohun's claims to not only get Raddie back, but also to charge the native police subordinates of sexual misconduct. For, the daroga, by allegedly cohabiting with Raddie, abused Mohun's proprietorial claims over her-her being either a slave-servant or an adopted daughter to him. And, if indeed she was a protected young mistress, the violation of Mohun's male and householder authority was apparent in this alleged misconduct by the daroga. Finally, Mohun's claims of Raddie being his adopted daughter, that is tied through claims of kinship, who had been sexually abused by public authorities, obviously meant the loss of patriarchal honour. In each of these possible scenarios—from property to kinship—the idea of ‘protection’ would remain crucial.

Stories such as those of Raddie and many more are bound to appear only in fragments in judicial and other archives. The servant-subaltern was not a concern of these archives.Footnote 8 In the case of Raddie, the issue at stake was not justice for the young girl, who complained of being beaten by her master/adopted father and mistress/adopted mother. It was, rather, whether the magistrate's dismissal of Dutt, the daroga, was justified.Footnote 9 Dutt might have faced the same trial had there been any other person involved, thus making Raddie's presence in the archives accidental. We have no way of knowing what happened to her once the trial was over, resulting in the revocation of Dutt's dismissal on grounds of insufficient evidence. She might have gone back to Mohun's house, found another master, or migrated to some other town or place. And, in each of these conditions, she might have found herself in a relationship of ‘protection’, including that of becoming a bibi to a European.Footnote 10

Young girls like Raddie's precarious condition as reconstructed through their fragmented historical presence leaves us only with speculative possibilities. Their stories do not fit into the usual explanation of lifecycle change attained through service and marriage by young girls in Western Europe in that period of time.Footnote 11 In colonial situations, the lifecycle element seems to be missing. An ageing male servant was habitually called a ‘boy’. Infantalization of male servants was part of the colonial project and continues to be practised in postcolonial upper-class families.Footnote 12

For female servants in India, and particularly for those who worked in native and not European households, there might have been a slight possibility of lifecycle change. In fact, this possibility is best captured in Raddie's own account of her dispute with Mohun's wife. When Raddie asked for clothes and rice, the wife told her to first get married and then ask her husband to provide for her. However, she insisted that Raddie would have to continue performing ‘drudgery’ in her ‘natal’ house even after the marriage, to which Raddie replied, ‘if I marry why should I do the drudgery of your House?’ In response to this retort, she was beaten. If, in Raddie's imagination, marriage would allow her to break the ‘ties of drudgery’, then perhaps it also could have created conditions for a lifecycle change. This argument is speculative because, while marriage for girls in South Asia represents a breaking of ties with their natal household, it does not necessarily free them from drudgery itself. Married women of the lower strata continue working as domestic servants.Footnote 13 For such women, ‘once a servant, always a servant’ might be not just a literary adage, but rather a lived reality.

The case of Ramdulal De-Sarkar, however, presents another variant of the type of relationship that was possible in the master's household. A leading Calcutta banian (trader–merchant–agent) who became rich through his association with the American trade, Ramdulal had very humble beginnings. Like Raddie, he was an orphan whose family had been displaced due to the Maratha incursions in 1751–52, but he was fortunate to have grandparents who brought him to Calcutta. The grandfather lived on ‘beggary’ while the grandmother became a cook in the house of Madanmohan Dutta, the diwan of the Export Warehouses.Footnote 14 The young Ramdulal was also included in the group of attendants and dependants in Dutta's household, where, along with Dutta's sons, he received lessons in Persian and accounting. As the story would have it, he impressed his master with his skill and, thanks to Dutta's encouragement and his own acumen, Ramdulal rose to become a prominent banian in the city.

Ramdulal's upper-caste status would have spared him from menial drudgery in his master's household, but he was certainly aware of his humble background. Later, he added the title of Sarkar to his name, proudly boasting that coffers could buy caste.Footnote 15 In Ramdulal's case, dependency and the protection offered by the master facilitated a different life trajectory. Peter Marshall has suggested that most of these banians were already men of some substance before entering into the service of Englishmen. In other words, they were already dominant figures whom the English association only helped to rise further.Footnote 16 Some, such as De-Sarkar, became men of substance while part of their master's household, by running small errands when not doing heavy chores and by using their skill as much as by relying on the master's goodwill.

Not all became millionaires like De-Sarkar, obviously, but some certainly secured decent jobs in offices. Calcutta in the late eighteenth century was the administrative centre of the emerging British rule, with a variety of revenue, judicial, trading, and private mercantile offices. The attendants, retainers, and servant-like characters moved between private and public employment. This was true for a class of ‘boys’ who accompanied munshis, the language instructors/account keepers, kerranies (clerks, writers, copyists), or other similar superior ‘servants’. These boys carried their masters’ writing apparatuses, their hookahs, their pikdaan (spittoon, for collecting spit from a chewed betel leaf) (see Figures 1–3), and held umbrellas for them. While doing these odd jobs, they picked up some Persian, learning to read and write sufficiently to obtain jobs on their masters’ recommendation. Some of them, according to Charles D'Oyly, raised ‘themselves into very comfortable and distinguished situations’.Footnote 17

Figure 1. A moonshee. © British Library Board, Add. Or. 765–812.

Figure 2. A cranee or native English writer. © British Library Board, Add. Or. 765–812.

Figure 3. A monshee (Persian reader). © British Library Board, Hindostanee Drawings, Add. Or. 121–170, no. 14.

Servant hierarchies

In the eighteenth-century accounts, we see two classes or groups of servants. Similar to the French case in which scribes, clerks, secretaries, farm managers, and a host of similar professional groups were considered upper-class servants, occupational groups in India such as banians, shroffs (the sarraf of the Mughal times, meaning moneylenders/changers), munshis (scribes, linguists, account keepers), clerks, chobdars (mace bearers), and khansamans (house stewards/butlers/head cooks) belonged to the naukar group (upper-class servants).Footnote 18

In contrast to naukars were chakars, who performed menial services. The number of these servants in a well-to-do household generally ranged between 20 and 30 but could, in fact, be higher.Footnote 19 They included khidmutgars (table attendants), bearers, aabdars (water coolers), barbers, cooks, tailors, washermen, masalchies (link boys/torch bearers), syces (horse groomers), grass cutters, mehtars (sweepers, waste cleaners), bheesties (water carriers), mallies (gardeners), durwans (doorkeepers/guards), doorias (dog keepers), and, additionally, in European households, ayahs.Footnote 20 Williamson provides a comprehensive list of naukars and chakars found in both European and native households. Based on whether or not they performed menial duties, his list includes nine naukars and 30 chakars.Footnote 21

Until the early nineteenth century, there were very few European females in India, and therefore there were far fewer female than male servants in European households.Footnote 22 In the wage lists from the earlier period, made for Europeans, we find four female servants (excluding female sweepers) and 19 male servants listed.Footnote 23 In contrast, in well-to-do native households, the usual female servants included, among others, cooks (like Ramdulal De-Sarkar's grandmother), paniharin (water-pitcher carriers), jatanwali (corn/flour grinders), dhye (maids), milkwomen, and mehtaranee (female sweepers) (see Figures 4–7).Footnote 24 In households of modest means, also there would be someone like Raddie.

Among the many determinants of servant hierarchy, such as status (naukar–chakar) and caste (a theme that this article is not taking up directly), gender was an important one and was directly related to the ways in which work itself was described in historical documents. Unlike for the terms naukar and chakar, neither early modern nor early colonial sources mention naukarani and chakrani (the female nouns) as distinct classificatory categories.Footnote 25 The most often cited and comprehensive glossary of British rule in India, Hobson-Jobson, fails to even mention many of the terms related to female servants.

The male-based classification of naukars and chakars noted in a majority of sources renders female servants marginal or invisible. Two aspects of the argument related to the feminization of domestic work should be noted. First, the work done by women, mostly domestic, is not considered work because it is unproductive and unseen. This argument, as we know, was vigorously critiqued by feminist academics and activists a few decades ago. The second aspect, however, is the critique of this intervention itself. In the intervention that took place around the issue of the wife's ‘unpaid household work’, the category of woman by and large remained an undifferentiated group. This runs the danger of equating mistresses and female servants.Footnote 26 As seen in Figure 8, elite women were also buyers of labour and services provided by female servants and service providers. We know very little about the nature of the intra-gendered work relationship between mistresses and female servants.Footnote 27

Figure 4. Paniharin. © British Library Board, Add. Or. 2674–2473.

Figure 5. Milkwoman. In fact, in the same album, a man is also depicted churning butter; the image is entitled ‘Butter man’. © British Library Board, Add. Or. 2674–2473.

Figure 6. Malin (female gardener/gardener's wife). © British Library Board, Wellesley Album, Add. Or. 1098–1235.

Figure 7. Mehtaranee. © British Library Board, Wellesley Album, Add. Or. 1098–1235.

Figure 8. ‘Confectioners Shop’, showing a man on the left side preparing sweetmeats and probably his wife selling products. A milkwoman is sitting on the right. © British Library Board, Wellesley Album, Add. Or. 1098–1235.

We can, however, enrich our understanding on the ‘enforced or distorted invisibility’ of women's work—a phrase used by Ramaswamy—if we use visual images from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Visuals, just like judicial or any other archives, also only present fragments of servants’ lives. They also have their own ‘grammar’ of production as well as genres of representation. But, methodologically speaking, reading social-life and work categories as represented in these images does open up the possibility of contextualized alternative thinking on domestic servants.

These images in which servants appear either as direct subjects of ‘artistic compilation’ or as indirect objects of orientalizing ethnography are also part of the ethnographic quest pursued by British officials. Among others, one set of this visual compilation deals with European lives in India in which servants appear quite frequently. Another corpus of this collection is on the lives and customs of Indians. A patient perusal of these materials convinces one of their formulaic (re)presentation, album after album. It was based upon capturing the social essence, moulded in the genre of picturesque depiction, as represented through work and caste, at times, taking both of them as interchangeable units. These images were meant to show the popular trades and professions, castes, and occupations to the British orientalizing gaze. A close reading of some of these images, together with the context of their production and readership, however, opens up the possibility of going beyond these formulaic depictions. Inserting our own readings into their grammar allows us to make some arguments about women and work. For instance, in most of the albums and visual sets depicting domestic servants in British households, the lone female servant is the ayah.Footnote 28 In certain other albums—those commissioned from European officials and prepared by native artists to show ‘caste and occupation’ and ‘trade and profession’ in India—this was not the case. In these, we get to see other types of female servants; in fact, the ayah is absent, which clearly means that these artists were using native households as models for showing individuals and groups.Footnote 29 Visual sources can thus help us identify the nature of the gendered labour force in different types of households.

Some tasks, such as selling vegetables, confectioneries, and milk, were performed by both genders.Footnote 30 But many others were highly gendered. Mughal paintings and early colonial visual archives show that men wove and women spun; women carried bricks while men worked as bricklayers; men milked cows and women prepared cow-dung cakes.Footnote 31 Some of these occupational groups were obviously not, strictly speaking, domestic servants. Barbers, milkmen/women, cow-keepers, gardeners, and washermen/women provided services to individuals, a set of households, and the larger community. However, depending on the nature of the household and the ways in which services were procured and organized (that is, the ties of patronage and dependency), some of them could have been based on the master–servant relationship. Even if not as a personal servant, most of them were involved in the housekeeping of their masters’ households.Footnote 32

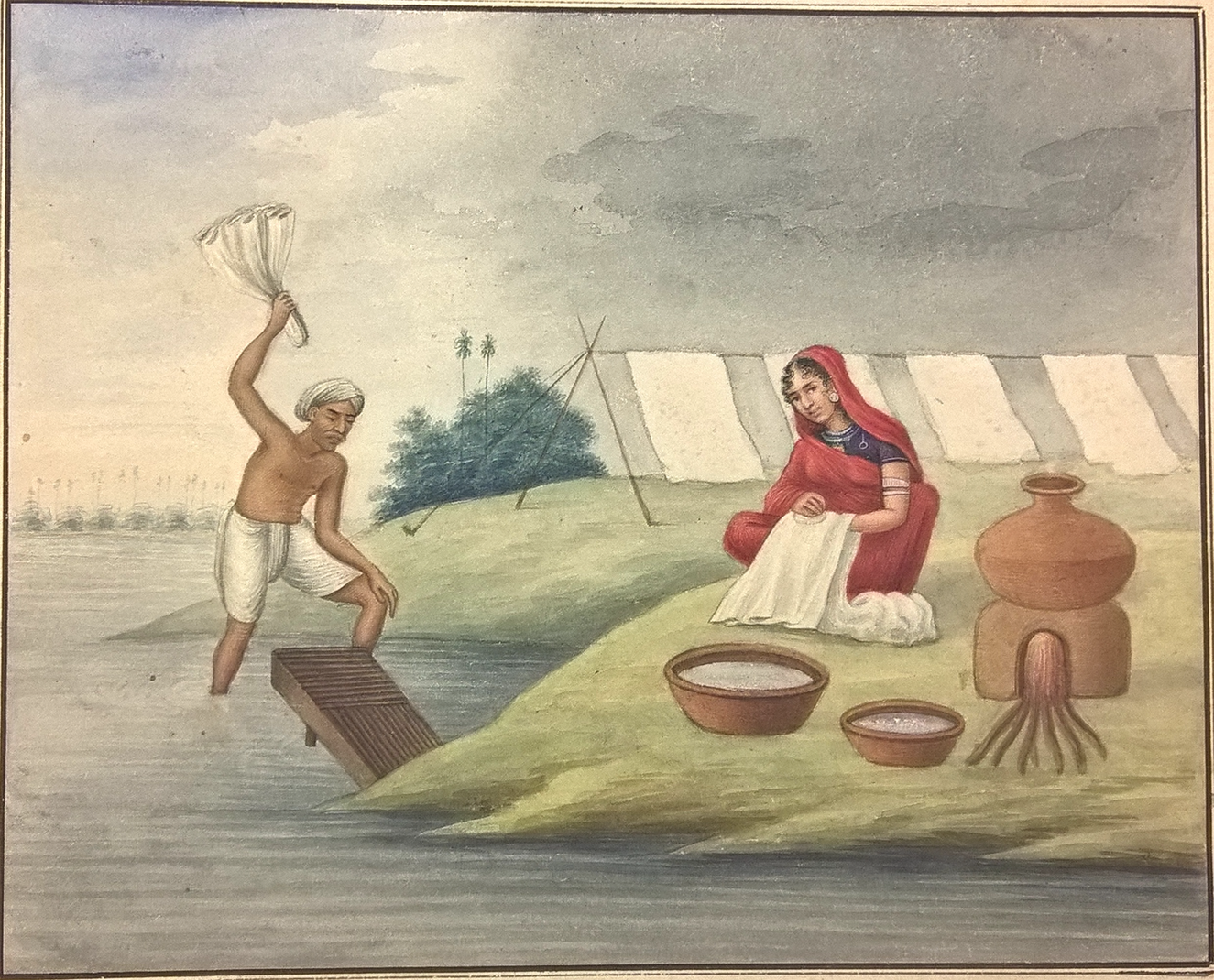

Many service groups and castes worked as couples (or in fact as households, including children). Yet again, in historical sources, the primary identification of that work hinges around the centrality of its male performer. The divergence between textual and visual sources is once again noticeable; the near absence of the couple as a category in the former is in contrast to its presence in the latter.Footnote 33 The wives of mehtars, called mehtaranees, were also employed as waste cleaners and scavengers but, while we sometimes hear about them in colonial ego-documents, they are still far less accounted for than their male counterparts. Washermen's wives (dhobin) in all likelihood did not do heavy washing, but provided support through other types of washing-related work (see Figure 9).Footnote 34 The malin (the wife of a mali, or female gardener) worked side by side with her husband, preparing garlands. Milkwomen not only churned milk for butter and prepared dung cakes, but also went to the market to sell their products.

Figure 9. Washerman and his wife. The painting is from the slightly later date of 1880, by Bani Lal. © British Library Board, Add. Or. 4006.

The question, then, is: what does the presence of a good number of female servants/service providers in/to native households tell us? It has been argued that the feminization of domestic work as well as of the term ‘servant’ itself occurred in other regions of the world much earlier than in India.Footnote 35 There are two meanings of the term feminization: one has a numerical basis—that is, were more women than men engaged in performing domestic service? In India, this became the case only in the 1960s.Footnote 36 Sources and secondary literature suggest that, prior to that, men outnumbered women in this role. The second meaning of feminization, however, is related to the social value of work—that is, the work performed by females that was not seen as valuable or productive. In this sense, we can see a longer history of feminization of domestic service in India.Footnote 37 In standard accounts, domestic work is identified with the male category—naukar and chakar—or for couples through male workers. But visual sources show us that females, either as independent servants or as wives, were a crucial part of the domestic-service economy. The fact that the wives’ labour was subsumed within the male category shows that the devalued labour of female domestic servants had a long history.

In the servant hierarchy that existed in the early colonial period, with strong precedents in the late precolonial period, the following points emerge. First, the presence of the pivotal figure of the lone female servant in European households, the ayah (and occasionally the mehtaranee and dhye), should not lead to a generalized picture of the near absence of female servants in the early colonial period. As domestic servants or domestic-service providers, they were present and could be seen at multiple sites of home, street, and bazaar. The likes of Raddie populated both the native households and the European ones; we simply hear less about them when compared to male servants. Second, the impression of the overt presence of male domestics may be a product of our own reliance on European textual sources, primarily ego-documents—that, too, their numerical greater presence might be a distinctive feature of European households. The above identification of a female workforce at the crossway of private households and public spaces (markets, ghats, gardens, and farm fields) does not overturn the argument of late feminization in the Indian case, but reminds us that a significant number of women were equally as important as their male counterparts in the sphere of domestic work.Footnote 38 Third, the presence of female servants also reminds us not to see ‘wives’ and ‘women’ as undifferentiated categories.Footnote 39 Historically, female servants have remained hidden behind their male counterparts and historiographically subsumed within the undifferentiated category ‘women’. The wife of the washerman applying soap on the clothes and Raddie's fragmented presence in the visual and judicial archives respectively reflect deep historical connections between women and work.

In addition to differentiation based on status and gender, in the fluid hierarchical world of servants, the tasks of certain menials such as mehtars and mallies and of washermen and barbers were caste-specific and hereditary. Others, such as khidmutgars, hookahburdars (one who took care of preparing the hookah), and aabdars, were not so. Although we have references from Mughal times indicating that servants kept to their own tasks, which indeed must have been based on the idea of social dignity attached to work, the occupational hereditary system, the caste hierarchy, and taboos related to touch and contact, the early colonial period had some important changes underway. Occupations crystallized into castes, but members of the same caste did different types of servile work. For instance, kahar—both an occupational and a caste category—had within it two sections. Members of one group were employed as durwans, while those of the other group were palanquin bearers; rules prohibiting their intermarriage existed. In his own lifetime, a kahar did different types of work. He tended his master's cattle in boyhood, became a household servant on becoming an adult, and, after his own marriage, was tied to his master as an agricultural worker. Girls worked as household servants but also sold milk and cow dung.Footnote 40

The strict employment-based division was more observable in aristocratic households than in those of lower officials. In the early eighteenth century, the khidmutgars of Anand Ram Mukhlis, the agent of the governor of Lahore at the Mughal court, doubled as cooks.Footnote 41 Such overlaps are also observable in British accounts. In fact, in British households, the possibility of occupational mobility was higher. After a certain number of years, a khidmutgar could become a khansaman. Khidmutgars themselves came from a range of social backgrounds both within and outside the household. On the one hand, the ayah's sons usually received this position but, on the other hand, a head bearer or jemmadar (head servant/head footman) could also be promoted to the rank of khidmutgar. Jemmadars along with soontahbardars or chobdars (mace and pole bearers, respectively) could themselves have moved up from the rank of hirrcarahs (depending on the nature of employment, meaning peon/messenger/spy). In the female sector, a mehtaranee could become an ayah in the European households.

Among menials also—that is, the group of chakars—distinctions based on rank and wage existed. A khidmutgar or head bearer was more respectable than a sweeper, gardener, or bheestie. The dignity of servants based on the performance of specific tasks was intrinsically attached to the class and rank of the masters. In the early nineteenth century, for instance, only households of rank and money employed both soontahbardars and chobdars. In such situations, both must have derived pride from doing their specific tasks and not doubling up for one another.

In general, occupational status, caste, and gender defined the servant hierarchy. The possibility of fluid movement, as we have seen, did exist. However, for servants standing at opposite ends of the spectrum of hierarchy, the status-based differentiation between naukars and chakars persisted, and early British commentators were aware of this. Williamson reminded his readers that it would be a great insult to a naukar if he were asked ‘whose chakar he [wa]s’.Footnote 42 A duftoree (office keeper) entrusted with keeping the office tidy would not sweep the floor, which was the task of a mehtar, who was a chakar.Footnote 43 The other markers of distinction appeared within the practices of permissibility. Munshis and banians were not required to remove their shoes in front of their British masters; all others had to be barefooted. The visual ethnography of colonial art maintained the same distinction between munshis and their servants (see Figures 1–3).

In the early colonial period of the late eighteenth century, the nature of service and servitude, the forms of employment, the hierarchy existing on the basis of social distinctions, and the occupational dignity based on proximity to the master or mistress were obviously influenced by earlier Mughal practices. The terms of service and servitude were not newly minted in the colonial period. For instance, the history of the terms ‘naukar’ and ‘chakar’ goes back at least to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, if not earlier. In the pre-Mughal period, naukari (service performed by naukars), in contrast to both chakari (work done by chakars) and bandagi (slavery), meant service with honour and respect. As Sunil Kumar has argued, a naukar was superior to a chakar; the latter term, according to him, meant domestic servant.Footnote 44 The emerging notion of naukari as a form of neologism was used to refer to people of the literate class, both those from Hindu scribal groups and skilled Persian migrants. They were more intimate with their masters and their honour and status were higher than those of chakars.

In the Mughal period between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, another strong social component was added to the meaning of naukar and naukari. In his seminal work, David Kolff has argued that, in this period, naukari emerged as a distinguishing form of military employment compensated by salary or other rewards and awards.Footnote 45 Prior to the Mughal period, in the Delhi Sultanate (from the early thirteenth to the early sixteenth centuries), military slavery was an important and well-established institution.Footnote 46 In the succeeding Mughal empire, this institution declined. With the exception of domestic slavery, the Mughals prohibited all use of slaves within their territory.Footnote 47 This, however, did not erase slavery completely; war captives, sale of children due to default in revenue payment, and famine kept replenishing the pool of slaves. As Irfan Habib has noted, ‘each scarcity was marked by a phenomenal glut in the slave market’.Footnote 48 In the domestic sphere, through the function of kinship formation, slavery remained an important connecting tie between family and political authority.Footnote 49 The presence of a male slave and a slave girl in ordinary households was noted by an early eighteenth-century author.Footnote 50 Nor did slavery mean the absence of wage labour; the Mughal urban centres of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries paid their labour force, including domestic servants, in money wages.Footnote 51 With this long view in mind, the following sections deal with the question of whether colonialism brought any change in the organization of domestic servants’ hierarchy or in the nature of work.

Old servants, new masters

Gradual shifts were taking place in the nature of work and the social distinctions attached to certain occupational groups from the early to the late eighteenth century. Let us look at some of the important groups that were defined as naukars. Serving in mercantile, royal, aristocratic, zamindari (of landlords), and British households, as well as in public institutions such as warehouses, custom houses, courts, jails, and revenue offices, naukars were both servants and masters. They were servants to their patrons and masters to men and women who performed menial tasks in their households, including ‘boys’ who held umbrellas over their heads.Footnote 52

Between the 1750s and the 1780s, working with European masters became extremely lucrative to banians and sircars (money agents, traders akin to Ramdulal De-Sarkar discussed above). They became owners of expansive garden houses, which were rented out to Britons, and adopted the lavish lifestyles of their European masters, so much so that it affected certain trades and artisanal occupations.Footnote 53 In a literary work from the early nineteenth century, a simpleton villager questions the new city-based Hindu elite's hiring of Muslim cooks. In other words, he accuses them of following English ways and discarding their own traditions.Footnote 54 In their role as commercial agents as well as doubling up as pointmen for the management of their masters’ households, ‘service as a banian became increasingly attractive after 1757’.Footnote 55 This change was undoubtedly linked to the increased political power of the EIC. Some munshis also maintained large households with numerous dependants. When Bunmally, a former servant of Ramkunt Monshee, broke into the latter's house with the aid of others one night, there were 64 people sleeping in the house.Footnote 56 These rich banians, sircars, and munshis dressed their servants in the uniform of the Company's sepoys and lascars. More than a decade earlier, it was noted that sepoys, stationed as guards at different locations, indiscriminately took things from the baskets of people passing to the market.Footnote 57 The red coat symbolized power, in this case the power to oppress. Even elites did not know how to deal with the power of the red coat, except petitioning.Footnote 58 The everyday authority flowed as much from institutional privilege and economic power as through the display of liveries and uniforms.Footnote 59 If the presence of servants added to the master's prestige, the power of the master gave servants a free hand.Footnote 60 Working in a European household, employment with the Company, and the liveries attached to these worksites started commanding more power. The native elites followed suit.

Figure 10. ‘A Bengal Sirkar.’ © British Library Board, Charles D'Oyly, P 2481, p. 90.

Figure 11. ‘Old Court House and Writers Building.’ © British Library Board, Thomas Daniell, http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/other/largeimage65495.html

An important member of the naukar servant group, the munshi, was in precolonial times bound to his patron in a dependent relationship akin to that of lord–servant and guru–disciple. The extent of the bonding was sometimes such that they would move along with their patrons and take their forenames as their surnames.Footnote 61 They were subordinate imperial secretaries in the Mughal polity educated in fiscal management, epistolography, accounting, and, not least, warfare, which exalted them to political positions. They were required to be discreet and virtuous and to display a grasp of the realities of politics.Footnote 62 Their expected realm of mastery, therefore, included a broad field of ministerial duties, spiritual gnosis, and secretarial art.Footnote 63

Muzaffar Alam and Sanjay Subrahmanyam have rightly described munshis as the real interlocutor for the English Company officials and as key knowledge brokers in the process of political transition to colonialism. The famous Orientalists of the late eighteenth century could not have produced English translations of Persian and Sanskrit texts without their assistance. These texts, as we know, were useful to the revenue and criminal judicial systems. However, it was precisely their streamlined role as language instructors and translation assistants that suggests that, by the early nineteenth century, the previously multilayered role of the munshi had been chipped away at.

In spite of its dependence on Mughal practices of administration and its personnel, the early colonial administration was mistrustful of Indians in matters relating to customs, laws, and practices. They relied on texts rather than the lived expertise of this group. The colonial administration, of course, provided some scope for professional diversification among literate groups. The courts, in particular, became an important source of employment. The ‘litigious’ Indians needed vakils (pleaders), who came from this literate group. A minority of munshi-pundits, who collaborated first privately with those Britons who were invested in the translation of legal texts and then institutionally to help judges in courts, also did well for themselves.Footnote 64 But those who remained in private employment—and there were many, because the newcomer cadets of the Company required them as language instructors—lost their erstwhile positions. They were now often described as ‘head of the servants’.Footnote 65 Through the disbursement of servants’ bills, munshis, banians, and sircars emerged as pointmen to organize their European masters’ households as well as to protect their masters’ secrets.Footnote 66

In fact, the management of the household was not exclusive to the public duties. Nobkissen, who acted as trusted mediator in Bengal wars and was raised to the position of ‘principal banyan for the affairs of the government’, continued managing his master Clive's household.Footnote 67 The list of cash accounts between Clive and Nobkissen for the month of January 1767, just before Clive departed from India the next month, tells us that Nobkissen discharged bills of tailors, ‘Portuguese boys’, Madras servants (for their house rent and clothes), ‘keepers’, general servants, a ‘slave boy’, and other charges related to birds and dogs. He also was responsible for clearing ‘table expenses’ that included liquors, cheese, pickles, hock, and sugar candies as well as ‘bazaar charges’. The other payments included ‘milk cow charges’ and ‘farm yard charges’.Footnote 68 As long as banians and sircars managed the private investments of European officials who otherwise were not allowed to trade privately, they remained in positions of privilege and confidence.

While we are clubbing munshi, banian, and sircar together because they significantly made the naukar group, a broad work-based distinction within them had emerged in colonial representations. Munshi had veered towards the work of language instruction or record-keeping in courts and other public offices. Banian and sircar, on the other hand, inhabited the world of commerce, of money and debt, of secret alliances and open litigations.Footnote 69

A similar shrinking of the meaning of the term and the remit of work is observable for khansamans. A khansaman in the Mughal period was a literate political figure; he was the high steward of the imperial household, commanded control over all personal staff of the emperor, was in charge of karkhanas (imperial production centres akin to factories), and kept an account of household expenditures. The wazirs (prime ministers) of the administration were drawn from the ranks of khan-i-samans (which was later contracted to khansamans).Footnote 70 In search of an equivalent to British butlers, khansamans of the late eighteenth century were shorn of their political role and reduced to simply running the household. These service terms were part of dictionaries and grammar books of the period. Their literacy was only applied to keeping the household-expense book, which anyway was hugely mistrusted. During the same years, when khansamans in British households were inevitably seen as cheats, the Mughal court at Shahjehanabad (Delhi) appointed one Mujdeddowlah to the office of khansaman with a gift of a turban, a fillet, and a keba (short coat). The Company state's own intelligence collected at the court shows that the khansaman was deeply engaged in politics and acted as a close confidante to the Mughal emperor.Footnote 71 The significant role of the khansaman in the political and economic set-up of large zamindari households is further evident in the list of ‘officers and servants’ employed under Rani Bhowany of the Rajshaye family in Bengal. On matters of revenue collection, the relationship between the queen and the Company state was difficult. The latter charged the former of evading payments, and therefore a list was prepared to determine how the land was farmed within the family. Four khansamans and two household servants appear on the list.Footnote 72

Finally, even for those belonging to the chakar group, this recasting, which also exposes the difference between European and native households, was underway. The khidmutgar went from being a trustworthy servant or personal attendant to being essentially a table attendant. The Mughal rikabdars (keepers of table crockery) are not encountered in any English accounts from this period. Contrast this with what still was the position of khidmutgars in native aristocratic households. The raja of Cooch-Behar dressed his khidmutgars in red coats to guard over zenana because the up-country sepoys, whom he called ‘strangers’, could not be trusted with guarding the space of zenana. Khidmutgars, in this case, were dependable private servants of the raja who could be trusted with arms to protect the women (honour) of the household.Footnote 73

The precolonial servant hierarchy retained its basic characteristics, but late eighteenth-century colonialism redefined the meanings of certain occupational terms and therefore the remit of work and relationships. First, this happened due to the search for equivalences. The culture and practices of the other needed to be rendered intelligible through one's own categories. Khansamans became butlers and munshis became linguists and language instructors. The sircar became a ‘money servant’ and the jemmadar a head servant. This was not the invention of categories so much as a reflection of the necessity to comprehend and control them. Treating upper-group servants as pointmen was a strategy used to fix accountability and responsibility for work done by others. Second, this gradual change in the servant hierarchy and service relationship was also taking place due to changes in the political economy. While some traditional learned aristocratic families lamented their loss of status and patronage due to the fading influence of Mughal rule, the political ascendancy of the EIC also created opportunities for upstarts. A host of financial service providers (from banians to shroffs, as seen above), a large number of linguist go-betweens (from dubhasis in Madras to munshis in the north and east), and a retinue of domestic servants became vital for Europeans in India. The marginals made their masters dependent on them just as the new masters set out to devise ways of controlling them.

In a letter on 29 August 1780, Mrs Eliza Fay described her life in India to her friends in London as living in a very comfortable house but ‘surrounded by a set of thieves’.Footnote 74 ‘Servant problem’ was the manifestation of this relationship between dependence and control—for the level of dependence was quite high. The servant-keeping culture of the Anglo-Indian society was a matter of imperial gossip and ‘inconsiderate censure’ back home. The English in India were in a fix to justify this dependence as well as to absolve themselves of the charge of indulgence.Footnote 75 Many newcomers found themselves in debt to their banians and sircars, but many of them also made money by trading in their banian and sircars’ names. A group of two to four Europeans living in a chummery surrounded by 100 servants required an explanation. Philip Frances wrote to John Burke:

Here I live, master of the finest house in Bengal, with a hundred servants, a country house, and spacious gardens, horses and carriages, yet so perverse in my nature, that the devil take me if I would not exchange the best dinner and the best company I ever saw in Bengal for a beefsteak and claret at the Horn, and let me choose my company.Footnote 76

A sheepish mixture of guilt and pride is evident in such longings for home while living like rulers in exile.

Caste and religion were often invoked in this situation. The need to hire so many servants was blamed on the caste taboos. The cultural prejudices of these servants allegedly forced their European masters to hire one individual for each specific task.Footnote 77 However, distrust accompanied dependence. In a variety of texts—prescriptive tracts, travelogues, and ego-documents—the servants of all classes were called ‘a race of vermin’, ‘the dregs of the people’, a ‘tribe of scoundrels’, and the ‘scum of their respective professions’.Footnote 78 To remain honourable in the eyes of friends, family, and other readers, one's servants had to be vilified. Dependency and indulgence could only be mitigated by representing servants as undependable. Visual images were not far behind in satirizing or caricaturing servants (see Figure 10).

Servants became a means to define and homogenize the colonized. However, the history of the master–servant relationship also shows how colonialism worked: through mutual distrust and dependence. This was manifest in everyday life as well as episodic events such as the siege of Calcutta in which the flight of the cooks left Britons starving.

On the night of 1 October 1754, a storm hit Calcutta. Almost two weeks later, the zemindar of Calcutta, J. Z. Holwell, petitioned the governing council describing the ‘extream [sic] distress’ the storm had caused to the poor inhabitants.Footnote 79 On behalf of ‘all menial servants, cooleys & workmen in the common Handycrafts’, he sought the Board's permission to remit a part of their ground rent until they recovered from the distress. The Board directed Holwell to provide all necessary relief but not to remit the payment of the ground rent, as it would set the wrong precedent. In 1759, the same Holwell proposed a set of measures to regulate the wages and work of domestic servants. In the expanding city of Calcutta, with its floating population, the ‘servant problem’ was not only about fixing terms and their meanings. Servant was as much a labouring identity as a social one. They were part of the urban labour pool, which needed to be regulated.

City and servants

For its buildings, open spaces, and British social life, Calcutta has been described as a city of palaces, opulence, and Oriental luxury. The viewers of the Calcutta panorama at Leicester Square were told that the city ‘has now become a capital worthy [of] so magnificent an empire’.Footnote 80 In numerous vibrant paintings and sketches, we notice this architectural opulence and the secluded sociability of Europeans (see Figure 11). What remains less noticed is the variety of labouring men and women on the streets and in the open spaces, at bungalows, and on the riverside that made the European seclusion possible. Households and public institutions required a large pool of men and women to perform manual work. The British empire in India could not have come into force without the bent back of coolies, the infected skin of boatmen, and the burst spleens of servants.Footnote 81 The textual details and visual depictions make it clear, as Peter Robb has recently argued, that the ‘regulation of labour and employment shaped Calcutta lives’.Footnote 82

Britons began living and practising their trade in Calcutta on a firmer footing at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Their history as well as that of the place as a cluster of villages goes further back in time, however.Footnote 83 As Farhat Hasan succinctly put it, Calcutta was not produced overnight by the touch of the English ‘magic-wand’.Footnote 84 It was already populated with a variety of working groups, merchants, and weavers long before Britons started gaining political and financial control in the 1760s.

Empiricists might discount legends as ‘puerile’ and ‘silly’ but the traces of labour and work are imprinted in the city's anecdotal past.Footnote 85 One legend that explains how Calcutta got its name goes like this: the first Englishman who landed there met with a grass cutter and inquired about the name of the place. The obscurity of the English language confused the grass cutter. He thought the gentleman was inquiring about the load on his head. He replied in a broken pidgin way: ‘kal kata’—that is, he had cut the grass yesterday. The Englishman gave the place the name Calcutta.Footnote 86 Another anecdote is related to dhobis (washermen), who had already by the 1780s earned infamy for damaging and misplacing the clothes of their masters.Footnote 87 The anecdote was first narrated in an 1830 text and then repeated in one from 1905. When the English arrived in Calcutta in 1620, they required translators and interpreters.Footnote 88 In Madras, these men were called dubas/dubhasis, meaning one who knows two languages. So, in Bengal, the English sought the same. The Bengali elite families to whom the request was made misinterpreted dubhasis as dhobis. They sent dhobis instead. As a result, anecdotally, it was believed that, in Calcutta, the washermen were the first service group who picked up some rudimentary English. One of them, Ratan Sarkar, was reportedly the first interpreter employed by the EIC.Footnote 89

These encounters show both the power of misapprehension and the possibility of social upward mobility. They also display the historicity of the place in terms of working groups. It is no surprise that grass cutters were one of the two most numerous menial groups; the other were palanquin bearers, who were known for their dominant collective solidarity.Footnote 90 The British presence in Calcutta of course led to further expansion. Under the EIC's zamindari, between the periods 1713–17 and 1743–47, the revenues from markets and marts, and grounds and houses, increased by 80 per cent.Footnote 91 An exact count has eluded historians for generations but, in all likelihood, the population of Calcutta, including nearby areas, grew from 30,000 in 1704 to 500,000 by the end of the century.Footnote 92

The regulation of 1759, whose details we will see below, worked in the context of the emerging urban beats of Calcutta. The songs of boatmen and palanquin bearers; the noise of loading, unloading, and ferrying bricks and chunam (lime) to feed the ‘construction boom’ of the late eighteenth century; and the mumbled and shrill voices bargaining with the hawkers who had mushroomed on Calcutta streets all contributed to the soundscape of the bustling city. Add to this the rattling noise of the wheels, the loud calls of syces, and screams of head servants and mace bearers alerting passers-by of the speeding carriages of sahibs and memsahibs. The history of the British conquest has looked closely at the macro picture of political economy and ideologies of rule. It has looked at intermediaries who collaborated with and resisted the British conquest. Banians, sircars, and munshis have been part of this historiography. ‘Intermediary collaboration’ has in fact become the mainstay of the frameworks used to understand the early colonial period. This article offers to understand the early colonial history through the teeming presence of labouring men and women of all sorts—people whose sound we can hear through delicate textual reading and whose presence we can see in the sketches and paintings of the period. This labouring group was both at households and at public sites of work.

Yet, historians disagree on the nature of Calcutta life. Critiquing a range of works that deal with intellectual or cultural encounters between Europeans and Indians in Calcutta, Marshall concludes that Britons who actively sought intellectual contact with Indians were a tiny minority.Footnote 93 A sizeable majority were just concerned with reproducing and sustaining their cultural life. Ranging from different subscription-based societies to those of wine merchants and booksellers, the society of white Calcutta was self-sufficient.Footnote 94 The opulence on display at public breakfasts, private parties, and numerous other celebrations marked its seclusion.

None of this is incorrect. If we change our angle of vision on the white life in the city from buildings to people, however, we will question the insularity. British cultural and social reproduction was based upon the labour of allegedly lazy and useless servants. The evenings in Calcutta, marked by strolls in the maidan (the iconic open space in the city) and the late-night merriment with drinks, dance, and flirting, had one essential thing in common: servants. Each master or mistress carried his or her own set of servants to parties. Their numbers sometimes became a nuisance for the host. In sending out the invitation to attend a concert and supper, Mr and Mrs Hastings asked their guests not to bring any servants except the hookahburdar.Footnote 95 When every guest brought their servants, the scene in the dining room became something like that shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. ‘Our Burra Khana’ (the dining room). Source: George F. Atkinson, Curry and Rice (on Forty Plates): The Ingredients of Social Life ‘Our’ Station in India, first published in 1860, fifth edition (London: W. Thacker & Co., 1911), no. 23.

The change in angle would also allow us to qualify the truism associated with the physical division of colonial cities into white and black parts. Again, Calcutta was no exception to this, but secluded sociability blinds us to recognizing that there was not just one, but two black towns in the city. The one lying to the north of the European settlement, which the subsequent writing on Calcutta presented as the main or only one, was inhabited by the native middle class and elites. The other, forgotten one existed to the south and south-east of the fort area, stretching from the prominent ‘cooley bazaar’ in the west, where Nundkumar was hanged, to the areas of Bhavanipur, Birjee, and Dollund to the south-east.

With the expansion of the European quarters, the straw huts of people such as Noor Mahmod Sarang, jamoll Colassey, and Domah Bearer had to make way for the Esplanade and for open spaces for the evening strolls and morning trots of memsahibs and sahibs.Footnote 96 Land taken in these areas and in Govindpur, where the new fort construction started in 1757, was only partly compensated for by grants of land outside Calcutta. Others received no compensation at all, even after almost ten years. One who lost land and continued to complain repeatedly was Hinghun Dhye.Footnote 97 The tearing down of dwellings of ayahs, sarangs, lascars, dhyes, servants, and coolies in these areas led to the proliferation of straw huts amidst the expansive colonnaded chunamed (washed-with-lime) brick bungalows of masters. But then such proximity was also not desirable. It exposed the white masters to fire and rats, and so the huts had to be ‘immediately removed’.Footnote 98

The occupancy of the British attracted many men in search of work to Calcutta. Clive must have carried this impression back home when he wrote to the Court of Directors, ‘Calcutta is daily encreasing [sic] in the number of inhabitants’.Footnote 99 Their presence also marked the institutional beginnings of defining the service relationships. In 1700, a zemindar or collector was appointed to the Council at Calcutta to oversee the collection of ground rent. His work included issuing pattas (lease deeds) to the inhabitants for the tenure of their houses and grounds.Footnote 100 But he also held a kahchari (court) in which he discharged all judicial matters related to revenue, both civil and criminal, pertaining to Indian inhabitants of the city. Along with this, there existed the Court of Cutcherry to try all civil disputes and the Court of Zemindary for criminal matters arising among natives. Both contemporary and later British accounts confirm that the zemindar wielded supreme authority and that his and the two other courts exercised absolute jurisdiction over natives within the district of Calcutta. The manner of justice was summary and the possible punishments included flogging, fine, work on the road, imprisonment, banishment from the settlement, and even death. The last needed the approval of the governor and his council. The Mayor's Court was set up in 1724, primarily to try disputes among Europeans but also those of natives with their consent. A Court of Requests was set up in 1753 especially for the poor inhabitants, to try cases involving smaller amounts.Footnote 101 Finally, in 1774, the Supreme Court was set up, and the Justices of the Peace also dealt with cases involving capital punishment given to natives. The formal acquisition of power by the EIC took place in 1765 and the revenue, judicial, and police reforms followed thereafter. However, Calcutta as a partial British enclave had already emerged by that time—that is, before the formal acquisition of power—which is attested by the growth in courts and the accompanying legal instruments to deal with civil and criminal matters. A majority of such legal forms of regulation were based upon and were giving shape to the master–servant relationship.

Servants’ history needs to be approached from both ends of the spatial spectrum: home and public. A closer look at the city helps map the traces of servants across different places in the city that comprised their social life as well as constituted parts of the master–servant relationships. As shown above, many types of servants of both naukar and chakar categories worked in households and public institutions. Many households in fact had office establishments within their precincts, blurring the division between private and public. And many offices had a ‘private’ set-up as well. On 2 February 1786, the day on which Sir William Jones delivered the third of his annual discourses at the Royal Asiatic Society, he left his house to reach the Court House at six o'clock in the morning. He was given a cold-bucket bath and dressed there. He also had his breakfast there before starting his language lessons with munshis.Footnote 102 As he made this journey from his house to the Court House, many servants must have accompanied him. Palanquin bearers, the head servant, mace bearers, barbers, masalchies, khidmutgars, and at least one cook must have been involved in making this tiny slice of the day memorable in Jones's life.

Servants moved in and out of the house. They worked at homes and offices. They met their counterparts from other households in bazaars, where they gossiped and quarrelled with them. They lived in common neighbourhoods of lascars, sepoys, and coolies. A long glance at Mughal history will throw up examples in which a domestic slave or servant started to work in a private capacity and moved up to assume a significant political role. In the early colonial period, we noted how the opportunity to work in offices arose for some of the literate groups of naukars. This was also true for menials. Bheesties, tailors, and gardeners, to name a few, found employment in the army, jails, and other institutions. The spatial movement within the city, and the fluid movement in identity, questions the strict binary between household and outside. Figuratively speaking, there was a process through which servants entered into and exited the household. That process was tied to the maintenance of the master–servant relationship through the use of the state's regulative apparatus.

There is, of course, something specific to Calcutta as well. The process of urbanization and the expansion of administrative mechanisms created a dynamism by which the urban labouring groups were not left untouched. Servants’ identity was on the one hand part of the relational social and private household worlds, while, on the other, it was threatening to cross the boundaries of the general urban labouring pool. Groups and individuals had come to Calcutta in search of work and money. The complexity of the slave–servant continuum and the vilified acts of servants were not the only subjects to worry about. The domestic servants were part of the growing urbanscape of Calcutta, which required legal interventions.

Law and servants

The status of coolie labour and of domestic or menial servants mutually structured some of the key aspects of the laws that were intended to regulate servants in early colonial India. Regulations were both a symptom of the historical reality of the possible overlap between a coolie and a servant, and a statement of intention on the part of the state to delineate a neat boundary between them.

Laws and regulations played a key role in the history of late eighteenth-century British and European domestic servants.Footnote 103 To summarize from Carolyn Steedman's work, in England, domestic service was articulated through law, labour, and the meaning of things. A servant tax that was extracted from the employers existed in England. Unlike the globalized care economy, which is supposedly informal and unregulated, eighteenth-century domestic service was regulated by law; servants’ presence was recognized by statutes and laws, and was therefore open to scrutiny and commentary.Footnote 104

In the colonial setting, things were messier than this. Colonies had their own pasts, including a complex servant-keeping culture. There existed a wide variety of terms and concepts, as shown above, to characterize the master–servant relationship, with differentiations as well as regional variations. The British presence created a dense legal structure, but some fundamental differences between the metropolis and the colony existed. For instance, there was no such thing as a servant tax in late eighteenth-century India. The centrality of law and regulation in forging ‘new’ relationships between the master and servant can be questioned, as Robb has done by suggesting that contract and law were inhibited by traditional law and forms of labour organization. According to him, the accent was more on household management, in which trust and sentiment played a bigger role than contractual relations.Footnote 105 However, any such view that posits a contrarian relationship between ‘tradition’ and ‘legalism’ as ways of organizing and controlling labour is misleading.

Very few historians have written specifically on eighteenth-century Calcutta labour. Notable amongst them are Marshall and Kaustubh Sengupta, whose works are separated by more than a quarter of a century.Footnote 106 Their writings focus primarily on coolies. To his credit, Marshall has looked at coolies and servants together, but with greater attention to the former. His central argument is that the Calcutta hinterlands failed to provide an adequate number of coolies as was required to cater to the ‘building boom’ of the city. His second argument is of direct relevance for this article. He argues that there existed a strict classification and separation between different types of labour such as craftsmen, coolies, and unskilled coolies. He does not say it in so many words but, if logically extended, his argument implies that such strict segregation also existed between coolies and servants. Sengupta concentrates solely on coolies and offers a mild criticism of Marshall, saying that the wage and work regulation initiated by the Company state in prohibiting private employment of certain categories of craftsmen and coolies explains the inadequacy of the labour supply. In other words, the reason for the inadequate supply need not be looked for in the existing structures of the agrarian hinterland, as Marshall does, but can be found in the policies of the Company state.

Both scholars, Sengupta more than Marshall, have left out the servants. That is not to suggest that those working on the history of coolies must say something about servants. But sources strongly indicate that their paths intersected and that the state's regulative attempts recognized it. The historian's inability to do so betrays a historiographical preference to readily discover labour that is in the public sphere. The binary of public and coolie on the one hand, and servant and household on the other, is thus created.Footnote 107 The servant–coolie conundrum, although short-lived in the context of urban Calcutta, promises to challenge this.

In May 1759, at a meeting of the quorum of zemindars of Calcutta town, three members—Richard Becher, William Frankland, and John Zephaniah Holwell—proposed a set of eight measures to the governor and the council.Footnote 108 Reflecting the spirit of the ‘united complaints of the inhabitants’, these measures proposed to regulate the wages and work of ‘menial servants’. The 24 categories of servants who came under the regulation were all chakars, with the exception of khansaman and chobdar. This was so because the intention was to regulate ‘servants in private service’. This clause was important because many of the naukars and chakars, as argued above, were also employed in public institutions. Thus, by fixing wages and laying out the terms and conditions of the master–servant relationship, the regulation itself can be seen as delineating the boundary of the private.

The basic points in the regulation were as follows. If a servant demanded more than the stipulated rate or quit the service without a month's notice, s/he was liable to be punished at the Court of Zemindary. The punishment could include attachment of their land, banishment with their family from the settlement, fine, imprisonment, and corporal punishment. If a master exceeded the rate, he forfeited the right of redressal at the court. Further, if he ill-treated his servant, the latter was ‘entitled to redress and releasement from his service’. But the servant was required to prove it through ‘regular complain’, meaning that s/he could not quit the service on the plea of ill-treatment without proving a complaint (or more than one—the meaning of the term ‘regular’ was left undefined) was made. Keeping in line with the English master-and-servant laws, masters were not subject to any corporal punishment.Footnote 109 The difference between boots and spleens was as legal as it was racial. In fact, in the colonies the master–servant laws strengthened the culture of violence.

Two unambiguous reasons were given for regulating servants: first, it was said that servants had become insolent and, second, that they had been demanding exorbitant wages. The exact reason of why this had happened was not clear, but it was firmly believed that the

root of these evils lie in our servants being admitted into the body of Sepoys, or received on the works of the new fortifications, and until the causes be removed by a positive prohibition from the President and Council, all attempts to redress their insolence and exaction will be rendered fruitless.Footnote 110

Sepoys, as described above, stationed at markets and public buildings in their red coats and carrying bayonets, symbolized power, which became the template for servants of other native elites. Coolies, employed in open public sites, perhaps were thought to carry the germ of defiance and disobedience. The social proximity between a sepoy (in the Company's employment) and a sipahi (native infantry), and the historical past of many such sipahis kept in private hire by zamindars and urban elites, explains why the slippage between sepoy and servant was possible (see Figure 8, showing the armed man escorting the lady making purchases). As a result, the resolution fixed the wages of the servants.

Coolie, on the other hand, was a generic term for one who provided waged manual labour. One could become and un-become a coolie, depending on work, worksite, and mode of payment. The term was already in use as a ‘suffix’ for some domestic servants, such as punkah coolie/bearer. The Company state participated in this process of ‘incompleteness’; in fact, it promoted it. The coolies that were brought to Calcutta to work on the fortification were ryots—that is, agricultural labourers. They ‘became’ coolies at the site of the fortification and repossessed the identity of farm labourers once back in the fields during the harvest season. But the Company and its officials also suffered from paranoia. They needed to make the categories self-evident and the meanings stable. Coolies, sepoys, and servants needed to be distinct and demarcated.

Regulation was a means for doing so. In March 1760, another resolution regarding servants was passed. The previous wage scale, with some changes, was confirmed. More importantly, it reiterated that ‘no menial servants, such as khitmutgars, musalchees, grass cutters, peons, & c., usually employed in the service of the inhabitants, be received as coolies on the new works or admitted as sepoys’.Footnote 111

And again, six years later, a third resolution came into force.Footnote 112 Three resolutions within a period of ten years show that, at least for the European residents of Calcutta, there was indeed a ‘servant problem’, which was, more importantly, a ‘labour problem’. The fact that the last one was proposed by the Committee of Inspection, which was formed the same year (1766) to supervise public works and deal with matters of payment to lascars and coolies, attests that the ‘servant problem’ was not just a ‘private’ matter of households, but was part of the Company state's attempt to regulate a variety of labouring groups. A new wage list was proposed. Another new element in this resolution was the proposal to set up ‘a Register of all servants of every denomination in Calcutta’. One Mr Stuart, along with an assistant named Mr Gideon Johnstone, were appointed to the office. The seriousness of the matter was evident, as the officials were directed to present the proceedings of the office every Monday to the Board.Footnote 113

‘The wretches have no shame.’ These were the words of Eliza Fay describing an incident related to her khansaman. The man had purchased a gallon of milk and 13 eggs for making a pint and a half of custard. Fay refused to foot the bill and the khansaman gave her a warning (to quit), which he eventually did. The mistress made it clear to the new khansaman that she had taken pains to acquaint herself with the market prices. The khansaman reportedly demanded double wages. He was instantly dismissed and the previous one was summoned and forgiven after he had paid a ritual homage. Fay reasoned with her distant friends (and also perhaps with herself): ‘I know him to be a rogue, and so are they all: but, as he understands me now, he will perhaps be induced to use rather more moderation in his attempts to defraud.’Footnote 114 Rehiring fired servants was not uncommon. Masters and mistresses did not always send their servants to the Court of Zemindary, as they were asked to do in the regulations.

Fay failed the Calcutta administration in not ‘blacklisting’ her khansamans, which was the purpose of maintaining the register. In fact, many Europeans and all Portuguese and Armenians failed to do this.Footnote 115 The office also never quite got on its feet. Within a year of the initial appointments, the posts had fallen vacant. Both officials had moved out of Calcutta. Time and again, the importance of the registry office was reiterated. The police superintendents raised the issue in the 1780s, and it was again discussed in the 1830s, 1850s, 1870s, and finally at the beginning of the twentieth century, when it was at last implemented in the hill station of Simla. Throughout the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the attempt to officially register servants failed. Writing in 1869, James Long called it a ‘paper resolution’.Footnote 116

Hay and Craven remind us that ‘details are crucial’ when looking at the actual working of the master–servant laws.Footnote 117 One of the central designs of the laws was to keep wages low and fixed. The repeated resolutions on wages confirm this intention, but details hint at their limitations. Between the 1750s and the 1780s, servants’ wages had doubled.Footnote 118 Thus, on both counts, registration and control of wages, these resolutions had minimal or no effect.

They do, however, seem to have had more of an effect on delineating the boundaries of work. The fortification work that saw the coming of the coolies to the city also spanned the same three decades when servants’ wages doubled. During these same decades, Europeans complained of the high cost of living in Calcutta. The house rent, the madeira wine, the handsome equipage, the pompous lifestyle, and the maintenance of a large retinue of servants made their living dear. Servants’ wages needed to be controlled to make the masters’ living cheaper.Footnote 119 Parallel to this, the wages of coolies, bricklayers, carpenters, and other urban labour groups needed to be regulated in order to finish public works on time and economically. And finally, as seen in the concerns of the 1759 and 1760 resolutions, servants and coolies themselves needed to be regulated from crossing the boundary between them.

In April 1760 (just a month after the second servant resolution), it was estimated that around one-sixth of the people presenting themselves as coolies at the fort were in fact not employed as coolies in the first place, but had infiltrated the coolie rank during the evening muster to receive daily wages. To prevent this, sepoys were positioned at stores and other places in the fort to prohibit the in-and-out movement of every ‘single black fellow’ without a pass before the muster. Failure to return the basket or any other tool given in the morning invited forfeiture of the day's wage.Footnote 120

The mode of payment was an important instrument of control. The practice of daily wage and evening muster was newly introduced for this purpose. Prior to this, coolies were brought in by sardars (headmen) and paid on a monthly basis. Furthermore, the sardars brought them on the basis of advance payment. Allegedly, the monthly-wage system had encouraged coolies to leave work early. The system also required a full establishment of account keepers such as sircars and banians that added to the cost of establishment. In order to reduce the cost of fortification and to improve the supply of coolies, magistrates and revenue farmers from outside Calcutta started directly sending coolies.Footnote 121 With this also came the change to the daily wage system to control coolies better and check infiltration.Footnote 122

The ‘pergunnah coolies’, as the outsiders were called, were largely agricultural labourers. In January 1758, while banning private inhabitants from hiring artificers, it was reasoned that, with proper encouragement, a sufficient number of coolies could be procured after the paddy harvest was finished.Footnote 123 The fact that coolies received advances and higher wages from private inhabitants was known to the administration, but it decided to wait before preventing them from hiring coolies.Footnote 124 The Company was confronted with two problems: first, the possibility of overlaps between labouring identities and, second, the differential mode of hiring and payment adopted by itself and private inhabitants for a number of working groups such as artificers, carpenters, bricklayers, and coolies.

The paddy harvest did not solve the ‘coolie problem’. In spite of the revenue farmers’ recourse to the system of advance payment of a month's wage (similar to sardars), coolies did not come into Calcutta in adequate numbers. At first, revenue farmers were penalized for not sending the contracted number but, later on, not only was the penalty withdrawn, but their advance investment was also reimbursed.Footnote 125 The district collectors criticized the whole system of coolie procurement, which, according to them, was based on force.Footnote 126 To quote in full:

for it is notorious that none will work on the new fortifications who are not compelled by force, when at the same time an individual may be get any number he wants at the same price as the Company allows. The farmers (or the collector for them) is [sic] ready to send in the number contracted for whenever a method is found to engage them to stay on the works, but till that is done the bringing them by force many miles from their town habitations to which they will return in a few days or flee the country for fear of being laid hold on again, of which there are many instances, can answer no end but that of the destruction of the Company's pergunnahs.Footnote 127